Chapter 1 - The Original People

Aboriginal people have lived in British Columbia for thousands of years. They were hunters and fishers who relied on the land and its many resources to provide everything they needed for their survival.

About 250 years ago the first Europeans arrived in British Columbia. They thought that they "discovered" the territory because no other explorers had been there before them. But British Columbia was already occupied by many different groups of people when the explorers arrived. They were the Aboriginal people, the ancient ancestors of the First Nations people who live in British Columbia today. More Aboriginal people lived in British Columbia in ancient times than in any other part of Canada.

These original people did not need to be discovered. They had been living in their territories for as long as anyone could remember.

Who were the original people? Where did they live? What was their life like in British Columbia before the Europeans arrived?

FAST FACTMore Aboriginal people lived in British Columbia than in any other part of Canada. |

Related Links: The First Nations Languages of BC

DIGGING UP THE PAST

Archaeologists have found evidence that people were living in British Columbia at least 10,500 years ago. This evidence consists of stone tools and spear points found buried in the ground at ancient hunting camps. The people who made these objects were big game hunters. They tracked down giant bison, moose, caribou and mountain sheep, killing them with stone spears. They ate the meat and used the skins to make tents and clothing. They were the distant ancestors of today's Aboriginal people.

As time passed the number of people living in British Columbia grew. They inhabited the valleys of the interior and the islands and inlets along the coast. Slowly they developed different languages and different ways of life. Over the years they evolved into the many Aboriginal groups that were present in British Columbia when the first explorers arrived.

PEOPLE OF THE COAST

The Aboriginal groups living along the seacoast followed a way of life that was different in many ways from groups living in the interior. On the coast the climate is mild and wet. Warm air blows in off the ocean and as it rises to cross the mountains it drops its load of moisture as rain. The BC coast is one of the wettest spots on earth. The moisture produces lush forests of cedar, spruce and hemlock trees. This is what is known as the coastal rain forest. It contains some of the tallest trees in the world.

The land on which the people lived had a strong influence on the way in which they lived. The rain forest provided the coastal people with everything they needed. They built large houses made from planks cut from the trees. They used the trunks of the trees to make their canoes, and bark and roots to weave clothing, mats, fishnets, rope and baskets. Today the people still use wood to carve the totem poles and masks that are such an important part of their culture.

On the coast, people lived by fishing, collecting shellfish and hunting seals and sea lions. Some even hunted the giant whales far from shore. Every spring a silvery fish called the eulachon swarms in huge numbers at the mouths of the rivers. These fish are very greasy. They provided fuel to burn for light, as well as oil to spread on food. When they dried, the eulachon burned just like a candle. The coastal people traded eulachon oil to other groups living in the interior.

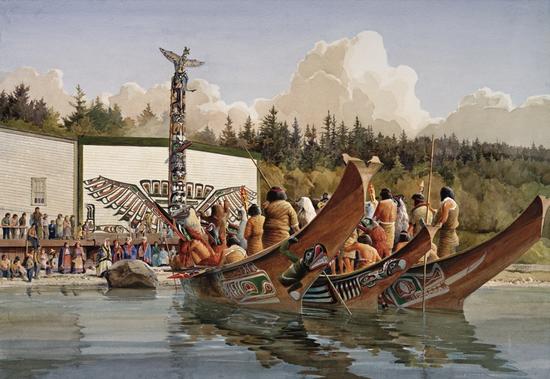

The people of the coast were sea-going people. Sometimes they lived on islands. Their villages were always at the water's edge. They had no roads or wheeled vehicles. They traveled everywhere by water in their log canoes. These canoes were beautifully shaped, polished and decorated with designs and carvings. They were works of art, made by trained artisans.

During the winter the people lived in large villages of many houses. It was during the winter, when the weather was bad, that they socialized and carried on their dances and religious ceremonies. When better weather came in the spring, they moved to smaller camps to fish, hunt seal and gather shellfish. Sometimes these camps were built atop middens. Middens are piles of discarded clam and oyster shells many metres deep. Archaeologists dig into the middens and discover evidence that people have used them for thousands of years.

|

BC Creatures PACIFIC SALMON

There are five types of Pacific salmon (top to bottom): sockeye, pink, chum, chinook and coho. Each type is slightly different in appearance and has different life habits. Fisheries and Oceans Canada |

PEOPLE OF THE INTERIOR

In the interior of British Columbia, Aboriginal groups lived a different kind of life. Here the climate was drier. It was much colder in the winter, and hotter in the summer. The people lived in small groups of one or two families. They moved around a lot, pursuing the deer, moose and caribou on which they depended for food.

In the interior, people lived in lodges made from animals skins, or sometimes in pit houses. Pit houses began with a shallow hole dug in the ground. A frame of poles was erected over the hole and covered with animal skins or dirt. The entrance was through the roof. This made a cosy shelter that kept the people warm in the winter.

Salmon was an important food for people in the interior. Salmon are born in the freshwater streams of the interior, then follow the rivers out to the sea. They remain in the oceans until it is time for them to return to fresh water to spawn near the same spot where they were born. As they made their way up the rivers of the interior, the Aboriginal people caught them in nets or speared them at the rapids. The people of the interior dried the salmon in the sun, or smoked them over open fires. Preserved in this way, the fish made a delicious meal all through the winter months.

During fishing season, the interior people came together in central villages. Here they met with their relatives, feasted and carried on important ceremonies. When the fishing was over, the people went away in smaller groups to hunt animals and to gather berries and roots.

|

BC Spotlight ABORIGINAL HOUSING

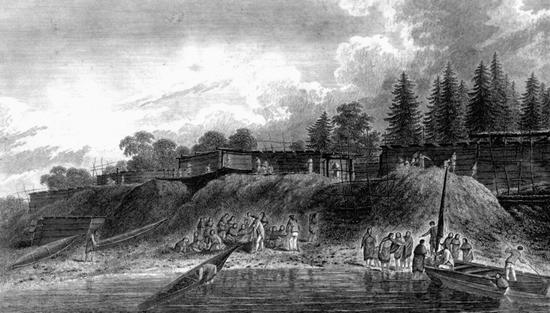

A drawing showing a view of a 3 Haida houses from the water with totem poles and a canoe on the beach.

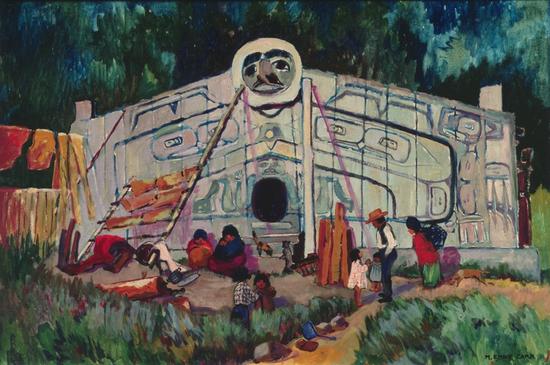

Aboriginal people on the coast lived in large dwellings known as longhouses, or bighouses. They were made of planks cut from cedar trees. Several families that were related to each other lived in each house. The outside of the house was decorated with paintings, and

|

NUU-CHAH-NULTH WHALERS

The Nuu-chah-nulth are a coastal people. For as long as anyone can remember, they have lived on the west coast of Vancouver Island. Like other coastal people, the Nuu-chah-nulth made their living from the sea. They fished for salmon and herring, hunted seals and sea lions, and gathered clams and oysters from the rocky shore. The meat and oil from these animals was stored for use during the winter months.

The Nuu-chah-nulth had a special skill. They were the only people on the coast to hunt whales. These giant animals swim past the coast of British Columbia on their way to and from their summer feeding grounds in Alaska. Standing on the beach, the Nuu-chah-nulth could see the whales splashing and blowing in the waves offshore.

The whale hunt required great courage and skill. Whalers enjoyed a special place in Nuu-chah-nulth society. They were usually chiefs who had spent years preparing themselves for the hunt. They learned the animal's habits and went through many rituals to try to influence the way it behaved. They bathed themselves in cold water, went for long periods without food, and sang special songs. They had to prove that they were worthy of matching themselves against the whale.

When they were ready, the members of a whaling crew climbed into their huge cedar canoe and set out into the open ocean. It was dangerous work. They would be gone for many days. A storm might blow up and overturn the canoe, or winds might carry them far from shore.

|

BC Creatures GIANTS OF THE SEAThere are many different kinds of whales in the ocean. The Nuu-chah-nulth hunted the gray whale, one of the largest species. Gray whales come from Mexico where they spend the winter in large, warm-water lagoons. At this time the females give birth and nurse their young. Early in the year the whales leave Mexico and swim up the coast of North America all the way to Alaska. It is a trip of about 9,500 kilometres. No other mammal travels as far in a single year. After spending the summer near Alaska getting fat on the tiny animals that live in the water there, the whales return to the south. It is on their way to and from Alaska that the whales pass the territory of the Nuu-chah-nulth. |

Once the whale was sighted, paddlers had to sneak up on it when it surfaced to take a breath. When they were almost on top of it, the chief thrust his long harpoon deep into the animal's back. Then the paddlers had to back away in a hurry. A wounded whale reacted with a violent slap of its tale, then dove below the surface to escape. If the canoe was too close, it could easily be swamped or smashed to pieces.

The chase was on. The harpoon was attached to the canoe by a long line. The fleeing whale pulled the hunters along behind it. They could do little but wait for the wounded animal to grow tired. When it came up for air, other harpoons were planted. Gradually the whale weakened from loss of blood until finally it died.

By this time the hunters might be far out to sea. They lashed the dead whale to the canoe and began the long paddle back to their village. It might take many days of hard labour. When finally they reached the beach, the whale was butchered and shared among all the people in the village. There was feasting and singing to thank the spirits for allowing the whale to be taken. The Nuu-chah-nulth believed that if the rituals were ignored they would be unsuccessful the next time they went hunting.

A single whale supplied tons of meat and oil for food, and bone to make tools and utensils. It was a way for hunters to show their skill and gain prestige in the village. All Nuu-chah-nulth respected a successful whaler.

Every year the hunters killed a few whales. One animal could feed a whole village, so there was no reason to kill very many.Then, beginning in the 1850s, American whalers began killing the gray whales in great numbers. So many of them died that for a while it was believed that the gray whale was extinct. The Nuu-chah-nulth had to give up whaling because there were no whales to hunt.The killing stopped in time, however. The animal survived and began to grow in numbers until today there are as many gray whales as there ever were. The Nuu-chah-nulth are even talking about hunting them again. Meanwhile the whales have become a tourist attraction. Large numbers of visitors to Nuu-chah-nulth territory travel in boats off the coast to see the whales in their natural habitat.

FAST FACTAn adult gray whale may grow up to 14 metres in length and weigh 30 tonnes. |

|

BC Places WHALERS' WASHING HOUSE

Canadian Museum of Civilization, 20512

This whaling shrine was located near the village of Yuquot (YOU-kwaht) on Vancouver Island. It was called the Whalers’ Washing House. It contained many carvedfigures of humans and whales. Hunters stopped here and washed themselves with purifying water before the hunt. In 1904 these particular items were sold to a museum in New York City, where they remain today. A group of Nuu-chah-nulth are trying to have them returned to their village. |

MAKING CONTACT

The Haida were the first Aboriginal group in BC to meet with Europeans. This happened in 1774 when the Santiago, a small Spanish sailing ship, arrived near one of the Queen Charlotte Islands on a voyage of exploration. A canoe carrying nine Haida paddlers came out from shore to have a look at the strangers, then more canoes came out. The Haida brought food and furs to trade, but before the Spanish could land a wind blew the Santiago away from the coast.

Four years later, in 1778, more ships appeared on the coast, this time in the territory of the Nuu-chah-nulth people. Captain James Cook was exploring the Pacific coast for the King of England. He brought his two ships, Discovery and Resolution, to Vancouver Island in search of a safe harbour and fresh water for his sailors.

When two people who were as different as the Nuu-chah-nulth and the explorers meet, they often do not understand each other. They are seeing so much for the first time. The Nuu-chah-nulth had not seen sailing ships before. They thought that the tall-masted vessels were floating houses. The British sailors did not understand the language of the Nuu-chah-nulth or the ceremonies that they used to welcome visitors to their territory.

The Nuu-chah-nulth people used to be known as the Nootka. This name came from a misunderstanding on the part of Captain Cook and his crew. The story goes thatCook motioned in the air with his finger and asked what the area round about was called. The people thought he was asking sailing directions. They told him to sail around the island, using a word that sounded like nootka. Cook thought they were telling him that they were the Nootka. That is what he called them and so they were called for many years. Only recently have the people begun to use their own name: Nuu-chah-nulth.

|

BC People CHIEF MAQUINNA

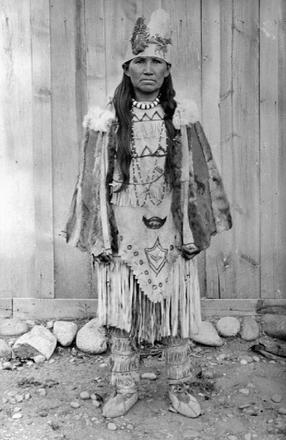

Chief Maquinna of Yuquot. The hat he is wearing shows scenes from a whale hunt. It was made from cedar bark and spruce roots. Only chiefs were allowed to wear the whaling hat. BC Archives A-02678

The leader of the Nuu-chah-nulth whom Captain Cook met, a chief named Maquinna, welcomed the strangers to his |

|

In Their Own Words JAMES KINGJames King, a sailor with Captain Cook, described what he saw when the Europeans approached shore in Nootka Sound:

"The first men that came would not approach the ships and seemed to eye us with astonishment, till the second boat came that had two men in it. The figure and actions of one of these men were truly frightful. He worked himself into the highest frenzy, uttering something between a howl and a song, holding a rattle in each hand. From time to time he took handfuls of red ochre and bird feathers and spread them in the sea. This was followed by a violent way of talking." Below is a painting by John Weber, another member of Cook’s crew. It shows the sailors trading at the village of Yuquot, or Friendly Cove, where the Nuu-chah-nulth people lived.

|

|

BC Places NAMING PLACESAboriginal people often take their names from physical features. The word Nuu-chah-nulth, which means “all along the mountains,” refers to the territory where the Nuu-chah-nulth people live, below the mountains on the coast of Vancouver Island. Ucluelet (you-CLEW-let) is an important Nuu-chah-nulth village. Its name means “wind blowing into the bay.” The village near where the people met Captain Cook became known as Friendly Cove. Its actual name is Yuquot, meaning “where the wind blows from all directions.” Wickaninnish, one of the beaches on the coast, is named after a local chief. Its name means “no one in front of him in the canoe,” which shows that he was the most important person in the community. |

THE POTLATCH

For many Aboriginal groups in British Columbia, the potlatch was their most important ceremony. Potlatch comes from the Nuu-chah-nulth word patshatl, meaning "giving". It refers to the fact that gift giving is an important part of the potlatch. So are dancing, songs, feasts and storytelling.

The potlatch is at the heart of the Aboriginal way of life. A potlatch is held at important times in the life of the community and the individual. Some potlatches are held to celebrate weddings, or to mourn the dead. Others celebrate the raising of a totem pole, or the naming of a new chief.

In the old days, potlatches took a long time to prepare and lasted for several weeks. Nowadays they usually last for a day or two. Guests receive presents from the host before they return home. The presents are a token of thanks to the guests for attending the potlatch and witnessing the important ceremonies that took place.

When Europeans arrived in British Columbia, they did not understand the potlatch. They saw the Aboriginal people gathering together to give away their possessions and they thought it was wasteful and evil. They wanted the people to give up their old ways and become more like Europeans. In 1885, the government outlawed the potlatch. Anyone taking part in the ceremonies was sent to jail.

The ban on the potlatch lasted for 65 years. It was a great blow to Aboriginal culture. The ceremonies which were such an important part of their life could not be held. The people were known for their wood carving of masks and headdresses. Most of these carvings were made for the potlatch ceremonies. Since they were no longer needed, the arts of the Aboriginal people went into decline.

The law did not stop the potlatch altogether. The people continued to hold a few ceremonies in secret, but they had to break the law to do so. Finally the government decided that the law was unjust. In 1951, the potlatch again became legal. Today it continues to be an important ceremony among the Aboriginal people, and once again the arts of the people are flourishing.

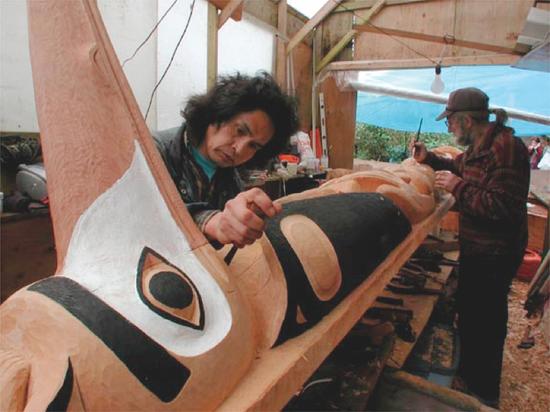

TOTEM POLES

One of the most familiar parts of Aboriginal culture in British Columbia is the totem pole. These tall pillars of carved wood stood in front of the villages. They were made by skilled carvers from a single cedar log.

Totem poles depict figures from Aboriginal history and legend and important crests and designs from the owner's own family. Anyone who understands what the designs mean can read a pole like a book.

There were different kinds of poles. Some stood on the beach in front of the village to welcome visitors. Others stood in front of a house to show the family history. Still others stood in the graveyard to honour dead relations. In all cases, the poles had great significance for the people.

Young carvers learn their skills by studying as apprentices with older carvers. They learn techniques handed down through many generations. In this way the Aboriginal people keep their traditions strong.

STORYTELLERS

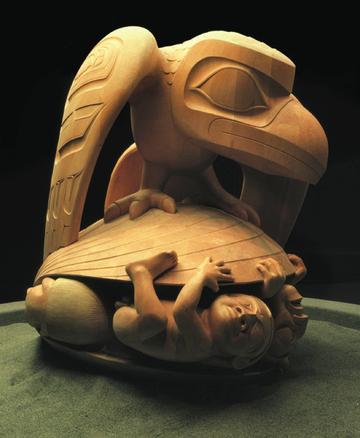

Long ago the Aboriginal people had no system of writing. Instead, they recorded their history and passed on their traditions in stories, songs and dances. Instead of reading books, an Aboriginal person learned by listening to the elders, watching the ceremonies and studying the objects made by artists.

Aboriginal art and stories often are about animals. The people believe that the way to learn about life is to study nature and learn from it. The lessons of nature are expressed in the art and ceremonies of the people.

Elders are very important people in Aboriginal society. They are respected advisors who use their knowledge and experience to guide the people. Elders keep alive the traditions of the people.

A NEW BEGINNING

The arrival of Europeans brought great changes to the Aboriginal world. The newcomers brought many things that were of value to Aboriginal people. Metal kettles, knives, guns and blankets were useful items that were quickly adopted by the people. In return they traded furs and food and shared their knowledge of what Europeans called the New World.

For many years life for the Aboriginal people went on much as before. The newcomers came from time to time in their ships, or set up small forts in the interior. The Aboriginal people traded with them from time to time, but their way of life did not change a great deal.

More and more outsiders arrived in British Columbia, however. They spread disease, used up the resources and threatened to take away the land. This presented a new challenge to the Aboriginal people. They had welcomed the newcomers into their land. Now they were learning to live with the consequences.

|

History Mystery THE VOYAGE OF FRANCIS DRAKE

In the summer of 1579, an English sailing captain named Francis Drake arrived in the Pacific Ocean in his ship, the Golden Hind. Drake was a pirate who made his living by raiding other ships belonging to the Spanish and stealing their cargo. He was also an explorer, and the Queen of England asked him to become the first English navigator to sail around the world. Drake’s voyage was a great secret because the Queen did not want anyone to know her plans. As a result, no one knows even today exactly where he went. We do know that he attacked many Spanish towns and ships in South America. Then he sailed north up the coast, past what is now California. Some say he reached Vancouver Island. Others think he got all the way to the Queen Charlotte Islands. Others say he did not reach British Columbia at all. Either way, it was two hundred years before Europeans again visited this part of the coast. Drake arrived back in England with the hold of his ship crammed with plunder. Queen Elizabeth made him a knight and he bought a great castle for himself. But Drake never stayed on dry land for long. He took part in many more naval battles against the Spanish. During one of these expeditions, he died of yellow fever. |