Chapter 2 - The Arrival of the Traders

Traders from many countries were attracted to British Columbia. They came in search of sea otter and beaver skins which the Aboriginal people offered in trade. The fur trade brought many changes for the Aboriginal people.

When Captain James Cook arrived near the village of Yuquot in 1778, some of his men traded with the Nuu-chah-nulth people who lived there. The sailors offered knives, blankets and metal tools. In return, they received food and furs.

After leaving the coast of British Columbia, Cook sailed his ships back across the Pacific Ocean to China. At the famous market city of Canton, his men sold their furs at a great profit. Chinese merchants were most impressed with the quality of the sea otter pelts. Thick and soft, they made the finest fur coats.

Before long word spread to other trading nations about the valuable furs. The result was a rush of ships to the coast of British Columbia.

IN SEARCH OF A PASSAGE

While the trade in furs flourished, exploration of the coast continued. The Spanish, who already owned Mexico to the south, hoped to expand into the north. The Russians were planning expeditions down from their posts in Alaska. And the British, thanks to Captain Cook's visit, thought that they had a claim on the area.

Into this confusing situation sailed Captain George Vancouver. He was one of the leading explorers in Great Britain. He came with orders to survey the coastline of North America between California and Alaska, and to enforce Britain's claim to ownership.

From 1792 to 1794 Vancouver and his men spent three summers on the coast. While their ship, the Discovery, waited offshore, they used smaller rowboats to look into every cove and inlet. The sailors sweated at the oars under the hot sun or through the driving rain. At night they camped in tents on the hard, rocky shore. It was exhausting work, but necessary. When they were finished, they had drawn the first accurate map of the British Columbia shoreline.

Meanwhile, the Russians withdrew from the coast, leaving the British and the Spanish to come to an agreement. Eventually the Spanish agreed to give up their claim. The two nations signed a treaty. Anyone could trade on the coast, but the area now belonged to Great Britain.

Of course, no one asked the Aboriginal people. As far as they were concerned the land belonged to them. After all, it had belonged to their ancestors for thousands of years. This different view of things continues right down to the present.

FAST FACTCaptain Vancouver’s ship, Discovery, was 29 metres long and had a crew of 86 sailors. |

THE SEA OTTER TRADE

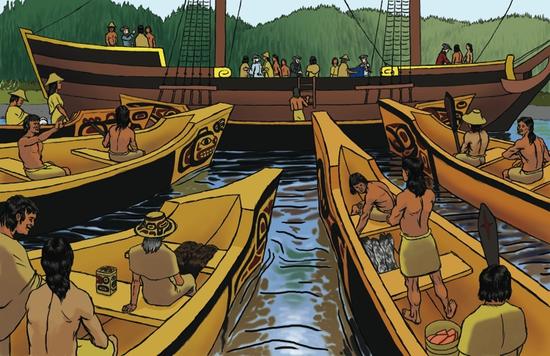

The traders came mainly from Great Britain and the United States. Each summer they sailed their small ships along the coast. When they came near a village, they sounded cannon to announce their arrival. The local Aboriginal people came out in canoes, bringing with them their furs to trade. When all the goods had been exchanged, the ship moved on to the next village. Before the autumn storms arrived, traders sailed across the Pacific to China where they bartered their furs for tea, silk and spices. These goods were much in demand in Europe.

The Aboriginal people were smart traders. They were used to trading among themselves and knew how to drive a hard bargain. They knew the goods they wanted, and how to haggle for the best price. At the height of the trade, vessels swarmed all over the coast. If one trader would not offer a fair price, the people could always wait for another vessel to come along.

The trade for sea otter pelts only lasted a few years. The demand was so high that thousands were slaughtered every year. By about 1820 so many of the animals had been killed that they were becoming hard to find. Sea-going traders were replaced by permanent trading posts. The focus of the fur trade shifted from the coastal villages to the rivers and lakes of the interior.

|

BC Creatures THE SEA OTTERIn the interior of British Columbia, and across the rest of North America, the fur trade was mainly a trade for beaver skins. On the coast, however, the most sought-after fur was the skin of the sea otter.The sea otter is a sleek, speedy animal related to the weasel. It spends most of its time in the water. It feeds by diving to the ocean floor to gather sea urchins and shellfish to eat. The sea otter is one of the few animals to use tools. When it finds a shellfish, it cracks it open with a stone to get at the meat inside.Sea otters grow thick coats of fur to keep themselves warm. This fur was worth ten times as much as a beaver pelt. It was so valuable that traders called it "soft gold".The trade in furs killed off almost all the sea otters on the Pacific coast. In 1911 an international treaty banned the hunt, but it was too late. Along the British Columbia coast, the animal disappeared. Then, during the 1960s, new animals from Alaska were moved to British Columbia. Today there are several hundred sea otters living in BC waters. |

CROSSING THE CONTINENT

At the same time as the sea otter traders were cruising the coastal waters in their ships, other traders were trying to find a route to the Pacific by land. For many years they had been trading with the Aboriginal people of the Plains and the eastern woodlands. The Rocky Mountains, however, threw up an impassable barrier that kept the traders out of the interior of British Columbia.

The fur trade in the rest of Canada was dominated by two large companies. The Hudson's Bay Company, owned by British financiers, traded from the shores of Hudson Bay. The North West Company was based in Montreal. Both companies operated a network of trading posts across the continent. And both companies wanted to discover a way across the mountains to the Pacific.

The North West Company sent one of their most experienced traders to find a route to the ocean. His name was Alexander Mackenzie. With the help of Aboriginal guides, Mackenzie made his way on foot through the snow-bound mountain passes. He came down out of the mountains to a great river, what is now called the Fraser. The explorers set off by canoe to see where the river would take them.

|

BC People FRANCES BARKLEYThe first European woman to visit British Columbia was Frances Barkley. When she was 17 years old, Frances married Charles William Barkley, a sea captain. Together the newlyweds set sail from England on a trading voyage in a ship called Imperial Eagle. It was a honeymoon unlike any other. First of all the ship almost sank in a raging storm. Then Captain Barkley came down with a fever and almost died. Finally, in June 1787, the Imperial Eagle reached Yuquot where it traded for furs. A few weeks later the Barkleys sailed south into a huge bay. They called it “Wickaninish's Sound” after the powerful chief who lived there. Today it is called Clayoquot Sound. Farther south the Barkleys visited another large inlet filled with beautiful islands. Today it is Barkley Sound and is a favourite spot with whale watchers and kayakers. The Barkleys had many more adventures on the high seas before they returned to their home in England. |

GREASE TRAILS

The Aboriginal people knew British Columbia well. They followed a network of footpaths that led from the coast to the interior. Along these trails they carried food and other items for trade between the different tribes. One of the most important trade items was oil from the eulachon fish. Each year the eulachon swarm in huge numbers at the mouths of the major coastal rivers. The eulachon is very greasy, and the Aboriginal people used the oil as fuel for lighting and also as a food delicacy. People from the coast carried the oil to the interior where it was much in demand. This is why the trails they followed became known as "Grease Trails".

It was down one of the Grease Trails that the Aboriginal guides led Alexander Mackenzie all the way to the Pacific. On July 22, 1793, they reached the mouth of the Bella Coola River where it empties into the Pacific. This made Mackenzie the first European to cross North America from the East. Strangely enough, he arrived at the ocean by land just a few weeks after Captain Vancouver's men had arrived at exactly the same spot by sea.

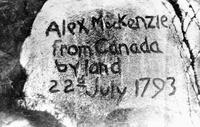

Mackenzie paddled to a rock and used a mixture of grease and dye to write: “Alexander Mackenzie, from Canada, by land, the twenty-second of July, one thousand seven hundred and ninety-three.” Visitors to the place can still read the message scrawled on the rock. Today it is preserved as an historic site.

|

BC Places MACKENZIE ROCK

BC Archives A-02312

Mackenzie paddled to a rock and used a mixture of grease and dye to write: Alexander Mackenzie, from Canada, by land, the twenty-second of July, one thousand seven hundred and ninety-three. Visitors to this place at Elcho Harbour in Dean Channel can still read the message scrawled on the rock. Today it is preserved as a historic site. |

FAST FACTStrangely enough, Mackenzie arrived at the ocean by land just a few weeks after Captain George Vancouver’s men had arrived at exactly the same spot by sea. |

RIVER TO THE SEA

Other traders followed Mackenzie into the western mountains. In 1805, they established the first trading post west of the Rocky Mountains, at a place called McLeod Lake.

One of the traders, Simon Fraser, led another expedition in search of a route to the Pacific. The route followed by Mackenzie was too difficult. Fraser hoped to find an easier passage.

In 1808, Fraser and his men set off by canoe down the river that now bears his name. Once again they relied on Aboriginal guides to show them the way. It was a terrifying trip through steep canyons and over swirling rapids. He stopped at several villages along the way. At one of these, a place called Kumsheen, the people were so excited to see him that he had to shake hands with every person in the village.

At last Fraser and his group reached the mouth of the river, near a place called Musqueam. But once again the river had proved to be too dangerous for regular use by fur trade canoes. Another trader later said of it, “I consider the passage down the river to be certain death, in nine attempts out of ten.”

The riddle of the rivers was finally solved by a third explorer, David Thompson. In 1811, he traveled down the Columbia River to the ocean. Unlike the other rivers, the Columbia turned out to be safe and convenient. Traders began using it as the main corridor connecting the interior with the coast.

|

In Their Own Words SIMON FRASERIn his journal, Simon Fraser described his canoe trip through the canyon of the river. I have been for a long period among the Rocky Mountains, but I have never seen anything equal to this country, for I cannot find words to describe our situation at times. We had to pass where no human being should venture. |

|

BC Places HELLS GATEThe narrowest point on the Fraser River is a place called Hells Gate. When the water is high in the spring, it rips through this gorge at over 30 kilometres an hour. |

FUR TRADE IN NEW CALEDONIA

When Simon Fraser arrived in northern British Columbia he called the area New Caledonia. The lakes and hills of the interior reminded him of his mother's stories of her home in Scotland, also known as Caledonia. Other traders called this area "the Siberia of the fur trade" because it was so far from home and so cold in the winter.

Fraser and his men were Nor'westers. They belonged to the North West Company, one of the two giant trading companies that controlled the trade. In New Caledonia the Nor'westers had a monopoly. For many years their rivals from the Hudson's Bay Company did not follow them across the mountains.

The Nor'westers built a string of trading posts across the interior of New Caledonia. One of these posts is now the modern city of Prince George. Another, Fort St James, is an historic site where some of the original building still stands.

Most of the men who worked for the North West Company were French-Canadian voyageurs.Or they were Metis, a mix of French and Aboriginal. For this reason the working language of the fur trade in British Columbia at this time was French.

It was difficult and expensive to import food to feed the traders at their isolated posts. They grew a few vegetables, but for the most part they relied for their survival on the Aboriginal people who brought fish, deer meat, berries and other food.

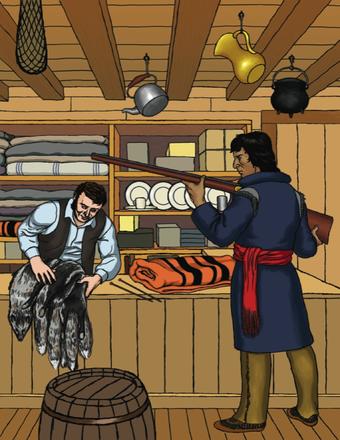

Aboriginal hunters also supplied the furs on which the trade was based. Mostly the traders wanted beaver furs, used to make fancy hats in Europe. But they also took muskrat, marten, fox and bearskins. During the winter the Aboriginal people traveled to their hunting grounds in small family groups. In the spring they brought their furs to the post where they traded for tools, guns, blankets and cloth.

Every summer the voyageurs loaded their canoes with the furs they had traded and began their long trip east. They crossed the Rocky Mountains by one of the high passes and descended to one of the company's trading posts in Alberta. There they dropped off the furs and picked up more trade items to take back with them to New Caledonia. It was the fur trade that first tied British Columbia to the rest of Canada.

THE HUDSON'S BAY COMPANY

In 1821 the Hudson's Bay Company absorbed its longtime rival, the North West Company. As a result of the merger, the Hudson's Bay Company took over all the Nor'west posts in New Caledonia. From 1821 the fur trade belonged solely to the Bay Company.

One of the changes made by the HBC was to set up trading posts closer to the coast. The first of these was Fort Langley, built on the Fraser River in 1827. It was followed by Fort Simpson and Fort McLoughlin in the north.

|

BC Places A FUR-TRADE FORT: Fort Langley National Historic Park

Fort Langley as it looks today. Mike Starr photo

Fort Langley was a typical fur trade post. As its name suggests, it was built like a small fort. A wall of logs surrounded an inner courtyard where there were rooms for the men, a dining hall, a warehouse, repair shops and a store where trading took place. Surrounding the fort were fields where the company grew potatoes, grain and other things to eat. The land around Fort Langley turned out to be so fertile that the post was soon growing produce for other posts in the territory. It took a lot of hard work to plant seeds, keep the fields free of weeds, and harvest the crop when it was ready. For this work the company hired Aboriginal people from nearby villages. Today this area of British Columbia is still the centre of farming in the province. At Fort Langley the traders also obtained salmon from the Aboriginal people. They salted it to keep it from going rotten, then packed it in barrels for shipment to Hawaii where it was sold. Over the years the buildings at Fort Langley fell into disrepair. Then, during the 1950s, to celebrate British Columbia's 100th birthday, some of the post was rebuilt. Today it is an historic site that people can visit to learn more about life in the early fur trade. |

For years the headquarters of the HBC trade was at Fort Vancouver on the Columbia River in what was called the Oregon Territory. Furs reached the fort from New Caledonia down a well-used route. Traders from all the interior posts brought in their furs by canoe to Fort Alexandria. There they were loaded on packhorses and carried overland along a trail to Fort Kamloops and down through the Okanagan Valley to the upper Columbia River. At this point the furs were put on boats that descended the river to Fort Vancouver where they would be loaded onto ships. Trade goods imported from Europe followed the same route, only in the opposite direction.

Great Britain and the HBC hoped to keep control of the Oregon territory, but in the 1840s American settlers began moving in from the East. The government of the United States served notice that it wanted Oregon for itself. For a while it looked as though Britain and the Americans might go to war over the issue. Finally, after years of negotiation, they reached a compromise. The Oregon Territory became part of the United States and the border with British territory was set at its present position along the 49th parallel of latitude.

The new border left the HBC with a bit of a problem. Its headquarters, Fort Vancouver, was now in American territory. The company decided to move north to Vancouver Island where it built a new post, Fort Victoria, overlooking a fine harbour. This small settlement became the headquarters of all the fur trade in British Columbia and it later became the provincial capital, Victoria.

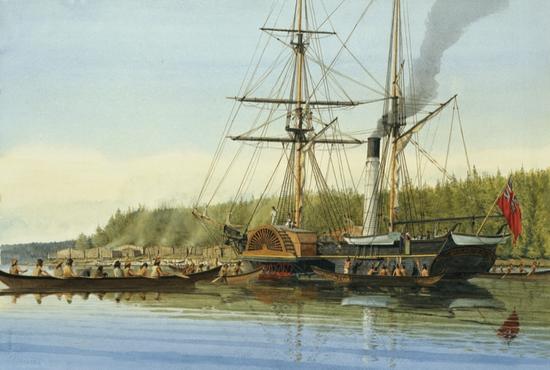

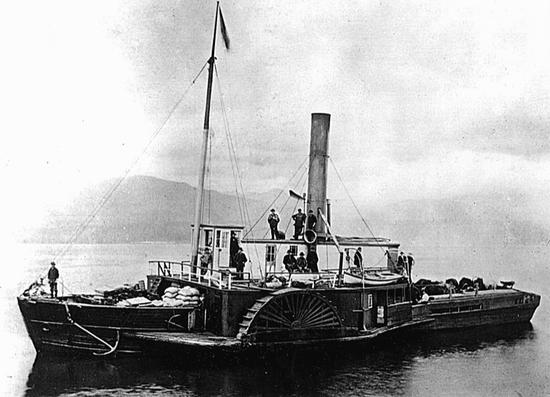

The Hudson’s Bay Company supplied the posts along the coast with trade goods and food by sailing ship. In 1836, there was great excitement at the posts when the company brought a new supply vessel out from England. Called Beaver, it was the first steam-powered ship on the Pacific coast. It was a sign that the Age of Sail was giving way to the Age of Steam.

A FUR TRADE LANGUAGE

When fur traders arrived on the coast they found many different Aboriginal groups speaking many different languages. The traders themselves spoke either French or English. In order for everyone to understand one another, people came up with a new language. It was called Chinook jargon.

Chinook jargon was mix of words—some English, some French, some Aboriginal, some entirely new. Anyone wanting to do business on the coast had to learn it. At one time Chinook jargon was spoken by a quarter of a million people. It died out with the end of the fur trade and now only a few people know it.

In Chinook jargon, tyeemeans chief; tillikum means friend; klahowyah means greetings, or hello; and cheechako means newcomer, or stranger. These are just a few of more than 700 words in this unique language.

|

BC Spotlight CHINOOK JARGONWords from the Chinook jargon dictionary:

tyee: chief These are just a few of more than seven hundred words in this unique language. |

ABORIGINAL PEOPLE AND THE FUR TRADE

Traders and Aboriginal people were partners in the fur business. Each needed the other. Traders supplied the Aboriginal people with goods they could not get elsewhere. Guns, kettles, blankets and needles were just some of the items the Aboriginal people came to value.

For their part, the Aboriginal people supplied the traders with valuable furs. As well, they guided the outsiders on their trips into the wilderness, and they provided food to the posts. The traders would not have been able to survive without the help of the Aboriginal people.

The fur trade did not lead to settlement. It required only a few posts scattered around the territory. The Aboriginal people did not have to fear that the traders were going to take their land.

Still, the fur trade did bring important changes for the Aboriginal people. They came to rely on goods from the outside world, and this gave the traders power over the Aboriginal people. As well, the trade introduced diseases that were common in Europe but unknown in North America. The Aboriginal people had no immunity to measles, smallpox, tuberculosis and whooping cough and they died in great numbers.

The worst epidemic occurred in 1862. In March, a sailor infected with smallpox arrived in Victoria aboard a sailing ship from California. The infection spread to the Aboriginal people who were camped around the outskirts of the fort. When they returned to their villages up the coast, they carried the disease with them. By summer the smallpox was passing up the rivers into the interior. For two years the epidemic raged. When it was over, about one third of all the Aboriginal people in British Columbia had died.

The spread of disease was the worst result of the contact between Europeans and Aboriginal people.

|

BC People THE KANAKASThe Hawaiian Islands are located in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, about halfway between North America and the Orient. Ships carrying furs and other goods from the Pacific coast to China stopped at these islands to take on supplies and do some trading. In those days they were called the Sandwich Islands. The Native people of the islands were good sailors. Some of them signed on as crew members of the trading ships. In this way they ended up in British Columbia, where they were known as Kanakas. (Kanaka is a word from the Pacific islands meaning “human being.”) Hawaiians helped to build Fort Langley and Fort Victoria. It was not unusual to find one or two working at any of the trading posts in New Caledonia. Most were men. Some of them married Aboriginal women and settled down to live in British Columbia permanently. Many people living in British Columbia today can trace their ancestry back to the original settlers from Hawaii. |

CREATING A COLONY

Even though the border between Oregon and British territory was established in 1846, the British feared that Americans might move north and claim even more territory. They decided the best way to prevent this was to send out British settlers to live on Vancouver Island.

FAST FACTAccording to the law at the time, a person needed to own at least 8 hectares of land to be allowed to vote. Only 43 colonists qualified. |

In 1849 the British declared the island to be a British colony. The Hudson's Bay Company received control of all the trade in the area. In return, the British government asked the company to bring out settlers and pay to get them established as farmers. For the time being the mainland was left to the Aboriginal people and the few traders who lived there.

Government of the colony was in the hands of Governor James Douglas and a few officials. The British insisted that an elected government should exist. In 1856, the first elections were held. According to the law at the time, a person needed to own at least eight hectares of land to qualify for the vote.This meant that only 43 colonists could cast a ballot in the election. Seven people were elected, and on August 12, 1856, the first elected government in what would become British Columbia held its first meeting.

Colonists on Vancouver Island grew crops to feed themselves and the fur trade posts. In the north of the island, coal mines produced coal that was sold to the British navy and in San Francisco. There was also some logging and sawmilling. Otherwise, Vancouver Island was a fur-trade outpost at the far edge of the world. One person described it as “a kind of England attached to the continent of North America.” Not many settlers wanted to come to live in such an isolated spot. It was left to the Hudson's Bay Company to rule pretty much as its own private fiefdom.

|

BC People A GOVERNOR AND HIS LADY

Amelia Connolly was a daughter of the fur trade. Her father, William Connolly, was the trader in charge of Fort St James in New Caledonia. Her mother was a Cree woman from the Prairies. Amelia had lived at many trading posts across Western Canada. In 1828, when she was 16 years old, Amelia married James Douglas, a clerk at the fort. They moved to Fort Vancouver where Douglas rose through the ranks to become the most important Hudson's Bay Company official on the coast. He founded Fort Victoria, and when Vancouver Island became a colony he became the governor. Amelia was now "First Lady" of the colony. She preferred the simple life of a fur trade post. But she learned to carry out the official duties of a governor's wife.

|