Chapter 3 - Gold Rush!

In 1858 prospectors arrived in British Columbia to look for gold. The rush of gold seekers lasted for several years. It led to the growth of business, the construction of roads and towns, and the creation of the first government on the mainland.

FROM FURS TO GOLD

The fur trade attracted very few settlers to British Columbia. Traders were interested only in collecting furs, not in starting farms or building towns. Besides, the interior of British Columbia was a sea of mountains. There did not seem to be a lot of good land for growing crops.

It was gold that brought the first flood of newcomers to British Columbia. During the 1850s, First Nations people began bringing pieces of the precious metal to trade. They found nuggets in the gravel banks of rivers flowing through the interior. For several years prospectors had been busy in California where rich finds of gold had been discovered. The California treasure trove was playing out, however, and gold seekers were looking elsewhere for new finds. When word leaked out that gold was present in the rivers of British Columbia, it touched off a stampede of miners.

FAST FACTOnly about 500 settlers and traders lived in Victoria before 30,000 prospectors and business people arrived. |

NEW ARRIVALS

The first group of gold seekers arrived at Fort Victoria by ship from San Francisco in March 1858. These men hit the jackpot when they found a rich deposit of gold in the Fraser River gravel at a place called Hill's Bar not far from Yale. When word of this discovery leaked out, the rush was on. As many as 30,000 newcomers arrived in Victoria in the space of a few months. Most were prospectors who immediately headed for the mainland. Others were business people who hoped to make a profit selling supplies. They purchased land and built stores and warehouses. Tiny Fort Victoria blossomed into an instant city. "Innumerable tents covered the ground as far as the eye could see," reported one observer. "The sound of hammer and axe was heard in every direction."

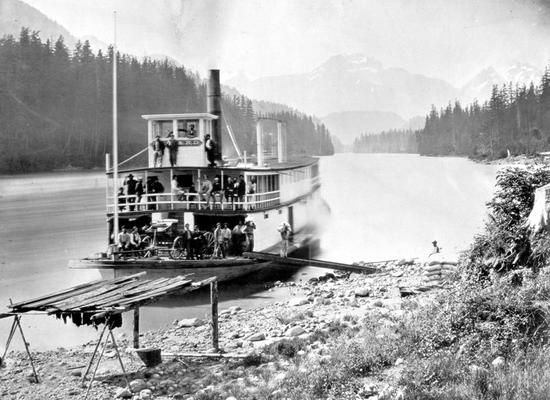

Prospectors heading for the gold fields had to cross Georgia Strait to the mainland using whatever means possible, whether it was paddlewheel steamboat, canoe, rowboat, or homemade raft. Some drowned in the headlong rush to be first to the gold. One eyewitness described the gold seekers. "Every man had his revolver and many a large knife also, hanging from a leather belt. I should say that the mining costume consists of a red shirt (flannel), blue trousers, boots to the knee and a broad brimmed felt hat, black, grey, or brown, with beard and mustache."

Once they reached the mouth of the river, they traveled upstream about 150 kilometres to the Fraser Canyon above Fort Hope where the water narrowed into a deep gorge. This was where the first gold was found, on the gravel banks and sand bars like Hill's Bar. Camps sprang up beside the river with names like Boston Bar, China Bar, Texas Bar and many others. The sleepy village of Yale became headquarters for the rush where prospectors bought supplies, banked their gold and caroused in the bars and saloons. Gamblers and thieves were as plentiful as miners, and most people slept with a gun under the pillow. In the opinion of one reporter, “a worse set of cut-throats and scoundrels never assembled anywhere.”

|

BC People

|

The First Nations people who lived in the area were not sure what to make of so many American gold seekers flooding into their land. The Fraser River between its mouth and Fort Yale was the territory of the Sto:lo people. Farther up the river beyond Yale was the territory of the Nlaka'pamux, “the people of the canyon ”. Both groups relied on the plentiful runs of salmon in the river for their livelihood. They were dismayed at the arrival of so many outsiders, who disrupted the fishery and overran their camps. The First Nations also came to believe that they should receive something in return for the gold that was in their territory. They blocked the river and drove the prospectors from their diggings. It was war, and lives were lost on both sides before peace was made.

But nothing could stop the miners, who moved like a rising tide north up the river, seeking gold in all the streams and valleys nearby. Most of all they were looking for the mother lode, the big vein of gold that was the source of all the grains and nuggets they had been collecting from the river. They traveled on the trails shown to them by the First Nations. Eventually they arrived at the Cariboo Mountains east of Quesnel where they made several of the biggest strikes. By the 1860s the Cariboo was the centre of the gold rush.

In the Cariboo, mining changed from the early days on the Fraser. Panning no longer produced most of the gold. Instead the miners began digging into the ground in search of the veins of precious ore that ran through the rock. They had to sink deep shafts and buy heavy equipment. All of this cost a lot of money. It was beyond the means of the lone prospector with not much more than a packsack of food and a pick axe. Gradually large companies bought up the mines, and prospectors became paid employees, labouring for a wage.

|

In Their Own Words THE LITTLE CAPITALAn early visitor, George Grant, described what Victoria was like in the early days: A walk through the streets of Victoria showed the little capital to be a small polyglot copy of the world. Its population is less that 5000; but almost every nationality is represented. Greek fishermen, Jewish and Scottish merchants, Chinese washermen, French, German and Yankee officeholders and butchers, negro waiters and sweeps, Australian farmers and other varieties of the race, rub against each other, apparently in the most friendly way. The sign boards tell their own tale."WonShing, washing and ironing"; "SamHang, ditto"; ‘KwongTai & Co., cigarstore"; "Magazin Francais”; “Teutonic Hall, lager beer”; "Scotch House”; “Adelphic” and “San Francisco” saloons; “Oriental” and “New England” restaurants.... From Ocean to Ocean, George Monro Grant (Prospero Books, 2000). |

BUILDING THE CARIBOO ROAD

The Cariboo was a long way from the coast. Steamboats could come up the river as far as Yale, but after that it was untracked wilderness. There were no roads, and the paths used by First Nations people were steep and dangerous. Pack horses fell and broke their legs. The woods were full of bears, and the mosquitoes and black flies drove prospectors crazy. The cost of carrying supplies to the mining camps was very high.

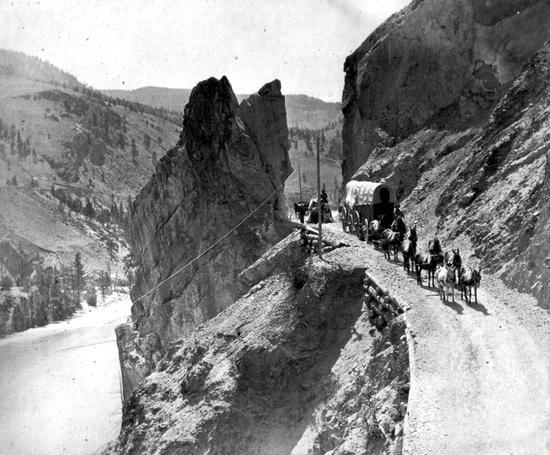

Governor James Douglas decided to build a wagon road to the gold fields. Work began at Yale, the southern end of the road, in the spring of 1862. For part of its route the road followed the Fraser River. It had to be carved out of the steep sides of the canyon walls. There was no heavy machinery. The road was built by hard labour, using explosives to blast a passage through the rock, then pick and shovel to remove the debris. Most of the work was done by Royal Engineers, a troop of soldiers sent out from England to enforce the law, survey the town sites, and build roads and bridges.

After three years of construction, the Cariboo Road reached Barkerville. It was 650 km long and cost well over $1 million to build. It greatly reduced the cost of carrying supplies to the gold fields. Travelers rattled along in stage coaches pulled by teams of horses. Every few kilometres there was a hotel, called a roadhouse, providing a meal and a bed to stay overnight.

|

BC People THE ROYAL ENGINEERSMuch of the Cariboo Road was planned and built by the Royal Engineers, a troop of soldiers sent out to BC from England in 1858. Besides building roads, the Engineers laid out new townsites, built trails and bridges, and enforced the law. They even had their own brass band, the first one in BC. After four years the Engineers were recalled to England, but many quit the army and stayed in BC to become pioneer settlers. |

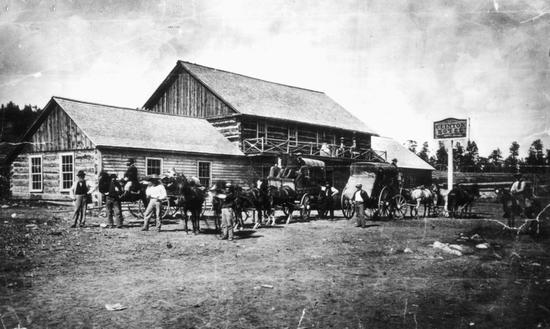

For fifty years, a familiar sight on the road were the red stage coaches belonging to Frank Barnard's express company, known simply as “The B.X.” Barnard's stages carried mail, freight, passengers and gold, lots of gold, between Yale and Barkerville. He even had his own ranch where he raised the finest horses. In winter, sleighs replaced the stagecoach. The B.X. was considered to be the longest stage line in North America.

BARKERVILLE: CAPITAL OF THE GOLD RUSH

Gold was discovered on the banks of Williams Creek in the heart of the Cariboo Mountains in the summer of 1862. Immediately a town sprang into being. It was called Barkerville after Billy Barker, one of the miners who made the big strike.

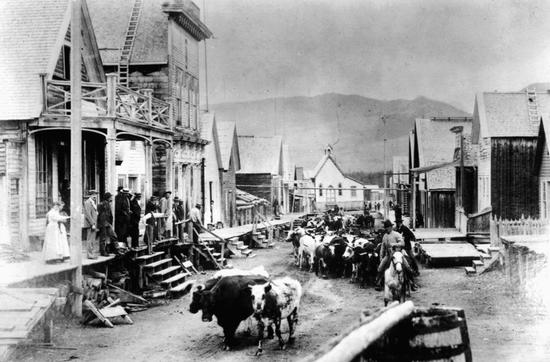

Barkerville was a typical gold rush town. The buildings were thrown together from whatever building materials were ready at hand. There were general stores, barber shops, laundries, restaurants, blacksmiths, churches, a newspaper and a sawmill. There were also several dance halls and saloons where the miners came to spend their earnings on liquor and gambling. At one end of town was a Chinatown where the Chinese miners lived. The sidewalks were made of boards, the streets of dirt. Animals wandered among the buildings feeding on garbage.

In a short time Barkerville was the largest community north of San Francisco with a population of 10,000 during the summer mining season. But it was struck by a devastating fire. In less than two hours, most of the town was burned to the ground. One eyewitness said that the fire started when a miner tried to kiss one of the girls in a saloon, fell against a stove and sparks from the chimney set the roof ablaze. The town was rebuilt, but the highpoint of the gold rush had passed. Prospectors began to drift away to look for gold elsewhere. Barkerville became a ghost town.

In 1958 the government of British Columbia rescued Barkerville. Because it had been such an important place during the gold rush, the government decided to make it a living museum. Workers restored many of the decaying old buildings. Today the entire town looks just as it did during the rush. Visitors can chat with actors dressed up as townspeople, stop in at the local saloon, go shopping at the general store, or find out how a mine really worked.

|

BC Spotlight A PROSPECTOR'S TOOLS

A

A gold pan (A) was like a big soup bowl with sloping sides. A prospector filled the pan with gravel and water, then carefully swirled the contents around. Gold is heavier than rock and gravel, so it sank to the bottom and stayed in the pan when the prospector poured off the water and other material.

B

A rocker (B) was a wooden box in which the prospector could wash large amounts of sand and gravel. The material was placed on a screen and water was poured over it. When a prospector jiggled the box with a handle, the gold separated from everything else and was caught in riffles, while the water carried away the rest.

C

A sluice box (C) was a long wooden structure open at both ends. When gravel was shovelled into the sluice and water was passed through it, the gold sank to the bottom and was collected in the riffles.

D

The prospector used a pickaxe (D) to break up the rock and dig out the pieces of gold.

|

|

BC Creatures CAMELSCamels? Surely camels live in the desert, not British Columbia. True enough, but during the gold rush, camels made a rare appearance in the Cariboo. The idea came from Frank Laumeister, who made his living packing supplies to the gold camps. He thought that the sure-footed animals would be perfectly suited to BC, so he bought twenty-four of them from the American army. But Laumeister hadn’t counted on the camels’ smell. The other pack animals—horses and mules—hated it, and ran away whenever a camel came near. Also their feet were too soft for the rocky trails. Laumeister was forced to sell his animals or put them out to pasture, and one by one they died. |

Related Links: Sketch of Barkerville

THE OVERLANDERS

Most prospectors who hurried to the gold rush were Americans, but not all. Some made the long trip across the continent from eastern Canada. These trekkers, inspired by the hope of striking it rich in the gold fields, were called Overlanders.

In June, 1862, a group of 150 Overlanders set off from Fort Garry in Manitoba to cross the Plains. Among them was one woman, Catherine Schubert, who was traveling with her husband, Augustus, and three children. She was pregnant with a fourth child, but she refused to be left behind.

FAST FACTIn 1862, it took Catherine Schubert and her family 135 days to make the trip from Manitoba to Kamloops. |

The Overlanders traveled by cart, horseback and foot. There were no roads, only dusty trails baked by the sun. Every morning they broke camp before dawn and trekked all day. Catherine carried her two babies in baskets slung over the back of a horse. Supplies had to be ferried across the many rivers on makeshift rafts. When rain came the rivers flooded, turning the prairie into a sea of mud. At the mountains, the travelers struggled up narrow trails and through deep canyons. Their supplies ran out and they had to survive on animals they killed along the way.

At last the Overlanders reached Fort Kamloops. At the First Nations village near the fort, Catherine gave birth to her baby. Then she and Augustus settled at Lillooet where they cleared a farm. While Augustus was away from home looking for gold, Catherine ran the local school and looked after the children. None of the Overlanders ever struck it rich in the gold fields, but many remained in British Columbia where they had successful careers.

FAST FACTNone of the Overlanders ever struck it rich in the goldfields, but many remained in British Columbia, where they built successful careers. |

CHINESE MINERS

Among the first boatload of prospectors to arrive in Victoria in 1858 were about 30 Chinese from San Francisco. These pioneers were followed by others, until by the height of the rush almost 3,000 Chinese were making a living in British Columbia, a place they called Gold Mountain. Most of them panned for gold in the creeks and riverbeds. They did not have the money necessary to sink the more permanent, underground mines.

Not all the Chinese newcomers were prospectors. Many were merchants who supplied food and supplies to the gold fields. Others ran businesses, such as laundries and restaurants. Still others worked as labourers on the Cariboo Road and other construction projects. In Victoria, Yale, Quesnel and Barkerville, they settled in their own neighbourhoods, called Chinatowns.

The Chinese suffered prejudice at the hands of White pioneers. They received lower pay for their work, and sometimes the other miners tried to keep them away from the diggings by force. But the Chinese miners were hard working. They often found gold where other miners had already given up. In time many earned enough to bring their families to live in British Columbia. These early pioneers formed the beginning of what is today the province's large Chinese community.

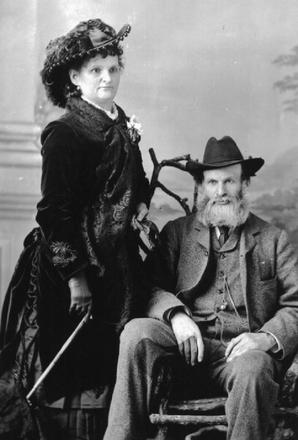

Hannah and Richard Maynard having their own picture taken. BC Archives A-01507

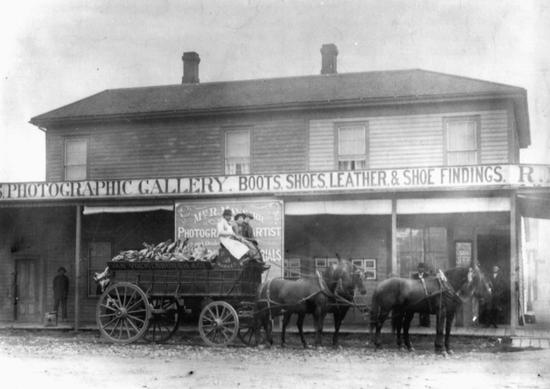

BC People PIONEER PHOTOGRAPHERSRichard Maynard came to BC from Ontario in search of gold. Having no success in the gold fields, he settled in Victoria. In 1862, his wife Hannah joined him there. Richard was a bootmaker by trade and opened a shop in Victoria. Hannah was a photographer, one of the earliest in Canada. She ran her own studio where people came to have their portraits taken. Richard learned from his wife to use a camera and in time he, too, became a photographer. Together they ran a successful business for many years

.

Hannah and Richard Maynard’s “Photographic Gallery and Boot and Shoe Store” in Victoria. BC Archives C-08995

|

CREATION OF A COLONY

When the American miners first arrived, Governor Douglas worried that the gold fields might become part of the United States. To avoid this happening, the British government in 1858 declared the mainland to be a British colony. Douglas was now governor of two colonies—Vancouver Island and British Columbia.

Governor Douglas took steps to create a stable society in British Columbia. He appointed officials to enforce the laws. He built roads to the interior, and established towns. He was assisted by Judge Matthew Begbie, a stern, bearded figure who traveled from mining camp to mining camp making sure that laws were being obeyed and peace was observed. "Boys," he once told a group of miners, "I'm here to keep order and administer the law. Those who don't want law and order can git. For boys, if there is shooting, there will be hanging." They called him "The Hanging Judge", but he was respected for being honest and fair.

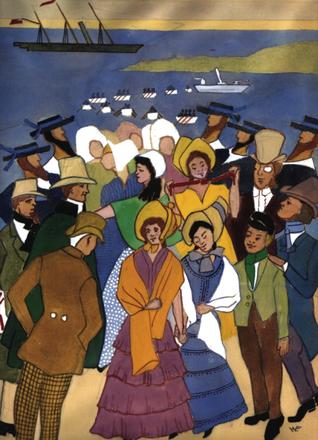

The colony attracted mainly men to its mining camps and fur trade posts. There was very little family life because there were so few women. Some of the newcomers took First Nations wives. But church and government leaders wanted to establish a European society in the colony. One answer was to import women from Britain. In 1862, several dozen young women arrived from London aboard two ships, called “brideships”. The plan was that they would work as servants and schoolteachers and eventually marry. Some of these women were widows whose husbands had died and left them in need. Others were working women who sought adventure or opportunity in the new colony. Still others were orphans, or young girls whose parents were too poor to look after them. In the end, most of them did marry and raise families.

The gold rush reached its peak in 1863 when about 10 tonnes of gold came out of the Cariboo creeks. After that the excitement began to cool off. Prospectors slowly began to drift away in search of other strikes, or to take up other professions.

But the gold rush changed British Columbia forever. It brought the first settlers to the mainland and led to the development of many communities. It provided customers for merchants, ranchers and farmers. A transportation network connected the interior to the coast. A legal system, a mail service and a police force were all in place. British Columbia was ready for the next stage in its development.