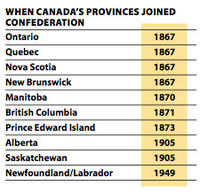

Chapter 4 - Joining Canada

Faced with a decision, people in British Columbia debated their future. Should they join the United States, or remain a colony of Great Britain? In the end they decided to join the new country of Canada that was taking shape on the other side of the mountains.

Related Links: Confederation for Kids

UNION OF THE COLONIES

Mainland British Columbia was created as a colony separate from Vancouver Island in 1858. The experiment soon turned out to be a failure. The construction of the Cariboo wagon road and all the other public works that followed the gold rush cost a lot of money. Both colonies were deeply in debt, and they were not attracting enough settlers to raise money from taxes or the sale of land. It seemed a waste to have the double expense of separate governments. In 1866, the colony of Vancouver Island merged with the mainland as a single colony called British Columbia.

|

BC Places THE FIRST CAPITAL

The waterfront at New Westminster in 1860. The ship is the Vickeray from San Francisco, the first vessel to load cargo at the little port. BC Archives B-06377

When the new mainland colony was created, a new city was founded on the banks of the Fraser River, on the site of a former Aboriginal village, and designated as the capital. At first it was named Queensborough, but Queen Victoria chose to call it New Westminster instead. When the two colonies joined in 1866, New Westminster remained the capital of British Columbia for two years until the seat of government moved to Victoria. At this time someone remarked that New Westminster was “nothing more than a small village built among the stumps of the forest.” |

As a colony, British Columbia was expected to provide wealth and services to Great Britain, the “Mother Country”. This was the basis of the system of colonies by which the great European powers carved up the globe. Overseas trade produced much wealth for the European economies. British Columbia, for example, produced gold and furs. It also was important for its location on the Pacific Ocean where it was a handy base for Great Britain's naval fleet. The lush forests provided timber to build ships and masts. When coal was discovered on Vancouver Island, mines were developed to provide fuel for the new steam engines that were being installed on British ships. Then, in 1862, the British navy decided to move its headquarters in the Pacific from Chile to Esquimalt, a protected harbour next door to Victoria. Ever since, Esquimalt has been an important naval base.

In return for these benefits, Great Britain paid for the defence of its colony and paid the cost of running the government. But increasingly, colonists in British Columbia grew unhappy with this arrangement. The world was changing around them. The gold was running out. The colony was deep in debt. Jobs were scarce and businesses were going broke. Colonists felt forced to make a decision about their future.

British Columbians felt that they had three options:

1. The colony was squeezed between two American territories: Oregon in the south and in the north, Alaska, purchased by the United States in 1867. Many residents were Americans by birth who had come to BC for the gold rush. The United States had a large, prosperous economy and, by 1862, a railway running right across the continent. Some British Columbians saw many advantages in becoming Americans.

2. Across the Rocky Mountains the new Dominion of Canada, created in 1867 out of four eastern provinces, was spreading across the interior. There was talk of a new railway running all the way to the Pacific. If they could make a good deal, there were advantages to becoming Canadian.

3. A small number of people wanted to leave things the way they were. These people were deeply attached to Great Britain. Many of them were officials in the old government who feared they would lose their positions under a new regime.

|

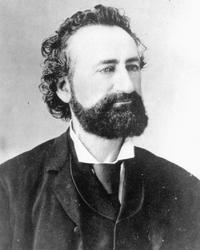

BC People LOVER OF THE UNIVERSE

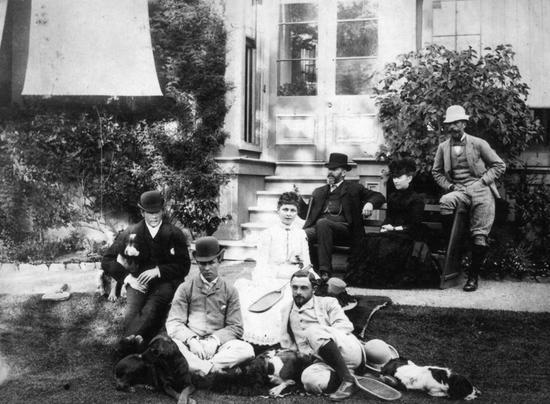

Amor de Cosmos, a feisty, dedicated politician, 1865. BC Archives A-01224

The Lover of the UniverseOne of the most unusual politicians British Columbia, or anywhere else, has ever seen was Bill Smith. Or, as he was more commonly known, Amor de Cosmos.Smith was born in Nova Scotia but, like so many others, he was attracted west by the gold rush. When he moved to California in search of gold he decided he needed a new name for a new country. He chose Amor de Cosmos, "Lover of the Universe".Moving north to BC, de Cosmos started a newspaper in Victoria and got involved in politics. A passionate speaker, he often got so carried away that he began hitting opponents on the head with his walking stick. He supported giving more power to the voting public instead of to appointed officials. He also supported union with Canada and worked tirelessly for the cause. Following Confederation, he was elected to parliament in Ottawa, then served a term as premier of British Columbia. When he tried to change the terms under which the province entered the union, an angry mob burst into the legislature threatening to lynch him. De Cosmos was forced to flee through a side door. Four days later he resigned as premier.In his later years he lived a lonely life as a recluse. He became quite eccentric and people shied away from him in the street. Still, de Cosmos is remembered as a fierce defender of democracy. As much as anyone he was responsible for British Columbia joining Canada. |

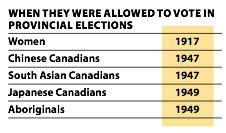

WHO COULD VOTE?

The government of the new province was elected, but that did not mean everyone had a vote. For one thing, politics was considered men's business. No women were allowed to take part in elections, not for many years. Neither were all men. In order to qualify, a man had to be 21 years of age or older; he had to have lived in BC for at least six months; and he had to be able to read and write. Furthermore, people of different ethnic backgrounds were excluded. In 1874, Aboriginal people and the Chinese lost the vote; so did Japanese-born people in 1895 and South Asians in 1907. These people were not allowed to take part in elections for many years. |

CONFEDERATION

The faction in favour of joining Canada was led by the fiery newspaper editor and politician, Amor de Cosmos. In 1868, he and some allies formed the Confederation League to build support for union with Canada. Their movement received a boost by the arrival of a new governor sent by the British to coax British Columbians into Confederation.

It soon became clear that most people favoured union with Canada, but not union at any price. In 1870, three delegates traveled to Ottawa to negotiate the terms under which British Columbia would become a province of Canada. They asked that Canada take over British Columbia's bulging debt and pay the new province an annual sum of money. They wanted a wagon road built across the Prairies to the west coast. And they asked for a more democratic form of government. Much to the surprise of the delegates, the Canadians not only agreed to these terms, they promised to build a railway instead of a wagon road.

Back home, the delegation was applauded for its work. Elections were held to find out how the people felt. The result was a complete victory for the supporters of Confederation, and the Canadian offer was quickly accepted. On July 20, 1871, British Columbia became Canada's sixth province.

Related Links: Klatsassin and the Chilcotin War

|

In Their Own Words A SUPPORTER OF CONFEDERATION SPEAKS OUTThe commissioner of lands and works, Joseph Trutch, explained why he supported Confederation with Canada: I advocate Confederation because it will secure the continuance of this Colony under the British Flag, and strengthen British interests on this Continent; and because it will benefit this community, by lessening taxation and giving increased revenue for local expenditure; by advancing the political status of the Colony; by securing the aid of the Dominion Government, who are, I believe, able to carry into effect measures tending to develop the natural resources, and to promote the prosperity of this Colony; and by affording, through a railway, the only means of acquiring a permanent population, which must come from east of the Rocky Mountains. |

DISEASE AND DEFIANCE

At the time of Confederation there were about 25,000 Aboriginal people living in the new province. That was far more than the non-Aboriginal population, but it was far less than the number of Aborginals who had lived there only a few years earlier. What had happened to make the number of BC's first inhabitants fall so rapidly?

In a word, the answer to that question is disease. Aboriginal people in North America had no immunity against many of the common illnesses brought to their land by Europeans. Epidemics of measles and smallpox swept away whole villages. One of the worst of the epidemics occurred in 1862. It began in Victoria where Aboriginal people from all over the coast gathered in the summer to trade and socialize. An American sailor from one of the ships was sick with smallpox and the disease spread to the Aboriginal camps. Once it was known that the camps were infected the townspeople chased away the visitors back to their villages. In this way the disease spread all over the territory, claiming thousands of lives before it finally petered out. It is estimated that this one epidemic killed one third of all the First Nations people living in British Columbia at the time.

The survivors tried to adjust to the arrival of settlers in their lands, but it was difficult. The newcomers had little respect for Aboriginal lifestyles. They did not understand how the people made their living from hunting and fishing. They did not know the deep attachment that Aboriginal people had to the land. Between 1850 and 1854, Governor James Douglas made agreements with several Aboriginal tribes on Vancouver Island. In return for blankets, small reserves and the promise that they could go on hunting and fishing, the tribes gave up their land to the newcomers. But these were the only agreements made in British Columbia for many years. For the most part settlers did not ask permission before taking possession of Aboriginal territory and imposing new forms of law and government.

From time to time Aboriginal people fought back. In 1864, a group of Tsilhqot'in (Chilcotin) attacked a road crew as it tried to build a road across the Chilcotin plateau in the central interior. It is not known for sure what caused the local people to take up arms. Apparently, members of the building crew were mistreating them. Perhaps, too, the Tsilhqot'in were fighting to protect their land from the intruders. At any rate, a group of soldiers marched to the area, arrested the murderers and, after a trial, hanged them.

On the coast there were similar acts of rebellion against the newcomers. And similarly the authorities responded with cannon and gunboats, forcing the tribes to give up their resistance. One elder spoke for all his people when he said:

“We see your ships and hear things that make our hearts grow faint. They say that more King-George-men [Whites] will soon be here, and will take our land, our firewood, our fishing grounds; that we shall be placed on a little spot, and shall to do everything according to the fancies of the King-George-men.”

The ways of the Aboriginal people were not the ways of the settlers, and so the settlers mistrusted them and shut them out of the new society they were creating. For the time being at least, Aboriginal people were treated as outsiders in their own land.

|

In Their Own Words KING-GEORGE-MENOne Aboriginal elder spoke for all his people when he said: We see your ships and hear things that make our hearts grow faint. They say that more King-George-men [whites] will soon be here, and will take our land, our firewood, our fishing grounds; that we shall be placed on a little spot, and shall do everything according to the fancies of the King-George-men.

A group of Aboriginal leaders at St. Mary’s Mission on the Fraser River, 1867. BC Archives O-09263

|

AT WAR OVER A PIG

Lyman Cutler was an American farmer who lived on San Juan Island, one of the islands lying between the mainland and the south end of Vancouver Island. One day in June, 1859, a pig wandered onto his land from a neighbouring farm. Perhaps thinking that pork chops would taste pretty good, Cutler shot the pig. And almost started a war.

The dead pig belonged to the Hudson's Bay Company, owner of the farm next door. The Company wanted to be paid for its loss and a judge was sent from Victoria. In response, American soldiers arrived to protect the rights of American citizens. Soon British warships were cruising offshore and Britain and the United States stood at the brink of war.

Obviously, the issue was much bigger than just a pig. The dispute was really over who owned San Juan Island. Was it part of British Columbia, or part of the United States? No one knew for sure. The border between the two follows the 49th parallel of latitude between the Rocky Mountains and the Pacific. When it reaches the ocean, the border dips south through Georgia Strait and around the bottom of Vancouver Island. But there is a maze of islands lying in the strait, San Juan Island being one of them. No one had ever decided for certain on which side of the border the islands lay.

In the end, war was averted. The island was shared until the true border could be decided. Finally, many years after Lyman Cutler shot his neighbour's pig, the United States took official possession of San Juan Island.

|

BC People WILLIAM DUNCAN OF METLAKATLA

William Duncan with Tsimshian children of Metlakatla. BC Archives A-01067

To the outside world, there was no place in British Columbia more famous than a small village far away on the north coast. Every visitor wanted to take the steamboat to Metlakatla (Met-lah-KAT-lah). What they saw astounded them. There were paved sidewalks lit by street lamps, a bustling sawmill, a firehall, a jail, a salmon cannery and the largest church north of San Francisco. It was, in the words of one tourist, “just like an English village.” What astonished the visitors was that the residents of Metlakatla were all local Tsimshian (SIM-shan) people. They had been led to Metlakatla by an English missionary, William Duncan. He came to the Tsimshian in 1857 to teach them about Christianity. Like other missionaries who came to BC, he did not think that Aboriginal religious beliefs had any value. He felt that Christianity was the only true religion, and that it was his duty to spread it to all the Aboriginal people. Duncan set to work at Fort Simpson. But he grew discouraged. The Tsimshian kept to their old ways and did not accept the new religion. Duncan decided the answer was to move to an isolated location, away from the trading fort. It was at this time that the terrible smallpox epidemic swept up the coast toward Fort Simpson. Duncan, who had medicine that would fight the smallpox, told the people that if they came with him, they would be safe. Several hundred Tsimshian followed him, and together they built the village of Metlakatla. Residents of Metlakatla had to obey strict rules. They had to give up their old religious beliefs and ceremonies. They had to stop drinking alcohol, gambling and painting their faces. All children had to attend school, and everyone had to rest on Sundays and attend church faithfully. The people even had to pay taxes: $2.50 a year, or a blanket. Duncan ran Metlakatla as if it were his own private country. He took orders from no one, which made him unpopular with officials in his church. After twenty-five years he decided it was time to move. Along with about 800 people from the village, he moved north into Alaska and established a new community. The old Metlakatla disappeared back into the forest. |

FINDING A ROUTE

British Columbia entered Confederation on the promise that a railway would be built linking the province to central and eastern Canada. But the railway was slow in coming. Politicians in Ottawa complained about the cost and tried to delay it. They called British Columbia "the spoiled child of Confederation" for demanding such an expensive project. This angered people west of the mountains, who began to wonder why they had bothered to join Confederation.

While the politicians argued, work on the railway did go ahead. The first step was to decide what route the track would follow. British Columbia was a sea of mountains from the Rockies to the coast. The only way through were the footpaths used by the Aboriginal people and a few rough wagon roads made by the gold miners. "It is going to cost you money to get through those canyons," one surveyor said. He was right.

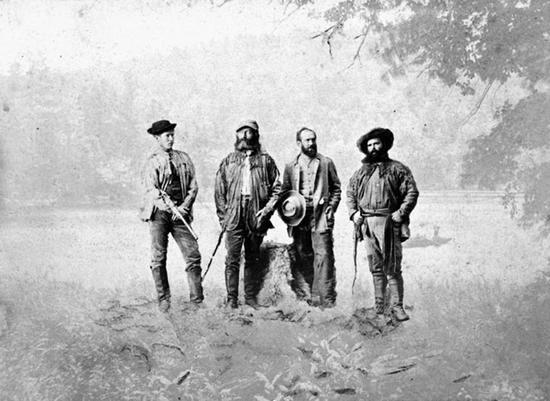

Finding a route through the mountains was a job for the surveyors. They were trained engineers, but they were also adventurers. They trekked through parts of the country that no white person had ever seen before, climbing tall mountains and wading across raging streams. One of these surveyors, Walter Moberly, found a pass through the Monashee Mountains. He called it Eagle Pass because he was drawn to it by following the flight of some of these majestic birds. Another surveyor was Major A.B. Rogers. His discovery of a route through the Selkirk Mountains is now called Rogers Pass.

|

In Their Own Words HUSTLE AND BUSTLE

A visitor described Yale, BC, in the 1880s during railway construction: A dance out here means business. The last one commenced at 12 o’clock on Monday morning and lasted continuously day and night until 12 o’clock the next Saturday.

|

BUILDING THE RAILWAY

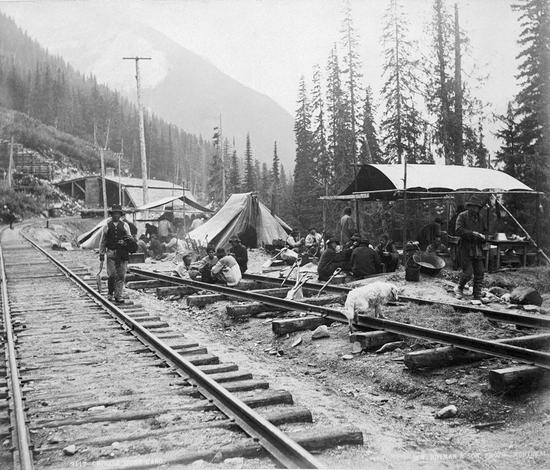

Finally, after a decade of bickering, British Columbia got its railway. A new company was formed to build it—the Canadian Pacific Railway Company, the CPR. In BC, construction began on May 15, 1880, at the town of Yale in the canyon of the Fraser River. Yale was as far up the river as steamboats could carry supplies from the coast before the rapids stopped them. From there the old Cariboo Road was used to haul building materials to the construction site.

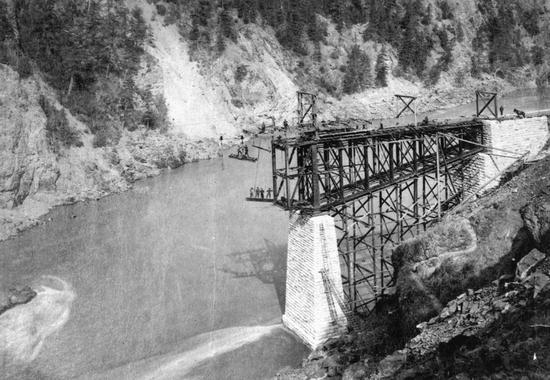

The person in charge of building the western section of the line was Andrew Onderdonk. He was an engineer from New York. The challenge facing Onderdonk was immense. He had to push a rail line along the steep walls of the Fraser River and through the mountains of the interior. On the flat prairies, rail builders were laying track at a rate of 10 kilometres every day. In the Fraser Canyon, it took 18 months just to blast four tunnels along a 2.5 kilometre stretch.

A century ago there were no machines to build the line; no bulldozers, cranes or trucks. Everything had to be done by workers using pick and shovel and horse-drawn wagon. The route followed the banks of the major rivers, but these banks were steep and rocky. At some places workers were let down on ropes over the side of the canyon to place dynamite charges for blasting. They worked in bare feet to improve their footing. Hundreds of wooden bridges carried the track across the deep gorges. Workers got so fast at building these bridges it was said that trains would run across a bridge in the evening that was made of timbers which had been trees just that morning.

One of the greatest challenges was the Big Hill. This was a very steep incline in the Rocky Mountains near the town of Field. It was almost 13 kilometres long, and was steeper than any other section of railway track in the world. The first train to come down it lost control and plunged into the river at the bottom, killing three people. Four powerful engines were needed to pull a train to the summit. On the downward run, special brakes were used and the trains crept along at slow speed. It was twenty years before the railway reduced the danger by replacing the Big Hill with a series of tunnels through the mountains.

FAST FACTSome railway workers suffered from scurvy, a disease that causes bleeding gums and bruises that don’t heal. Scurvy is caused by a lack of Vitamin C, which is found in fresh fruit and vegetables. |

CHINESE WORKERS

Faced with a shortage of workers, Onderdonk imported about 17,000 Chinese labourers to work on the railway. They were paid $1 a day, which was much less than the other workers received. The foremen gave the Chinese the most dangerous job of laying dynamite to blast a path through the rock. About 600 Chinese workers died, crushed in landslides, blown up in explosions, or sick with scurvy in the camps.

Without the Chinese, the railway might not have been built at all. It would have been too expensive. Yet they were considered transients, allowed in the country only to build the railway. When they were no longer needed, they were simply laid off. Once the railway was finished, the government introduced laws making it very difficult for Chinese to enter Canada.

THE CREATION OF VANCOUVER

Vancouver began as a port—a small group of shacks huddled around a sawmill on the shores of Burrard Inlet. Ships from around the world came to the mill to load lumber. The tiny logging village was called Granville. It was also known as Gastown after its most famous resident, the gossipy tavern keeper “Gassy Jack” Deighton.

Then, in 1884, the CPR decided to build the railway to the shores of Burrard Inlet at Granville. This would make it easier to exchange cargo between the trains and sea-going vessels from Asia and Australia. Two years later the city was established as Vancouver, named for the British explorer Captain George Vancouver.

Less than three months after it was born, Vancouver was almost destroyed. On June 13, 1886, a great fire swept through the settlement. At least eleven people died, and most of the wooden buildings were reduced to ashes.

But there was no destroying Vancouver. The fire took place on Sunday. By Wednesday, a brand new three-storey hotel was open for business and many other buildings were under construction. On May 23, 1887, the first passenger train arrived from Montreal and Canada’s port on the Pacific was bursting with activity.

FAST FACTThe Vancouver fire of 1886 spread so quickly that it took less than one hour to burn the whole city. |

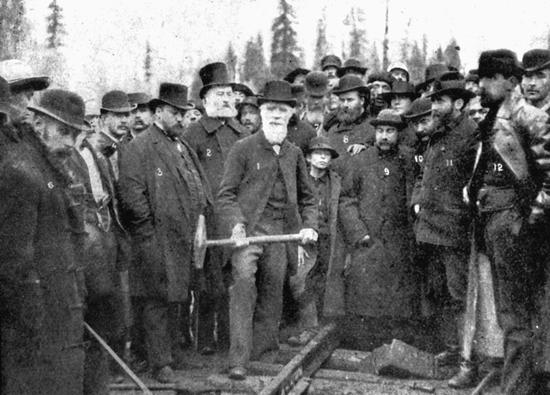

THE LAST SPIKE

While Onderdonk and his workers were building the railway from the coast toward the interior, other crews were building west across the mountains from the plains. The two ends met in the middle of the province at a place called Craigellachie on November 7, 1885. The president of the railway, Donald Smith, came out from Montreal. In front of a small group of dignitaries, he hammered the last spike to complete the job. The dream of a railway running right across the continent from Montreal to Vancouver was now a reality.

The impact of the railway on British Columbia was profound. It was an iron thread attaching the Pacific province to the rest of Canada. All along the route, towns sprang into life. Vancouver, the western terminus of the line, grew into a bustling port city. Wheat from the Prairies was carried out to the coast to be exported by ship around the world. In the other direction, timber from coastal forests was carried to the Prairies to build homes for the new settlers arriving there. The money used to build the railway gave a boost to the local economy. It seemed to British Columbians that they had chosen wisely by choosing to make their future as Canadians.