Chapter 5 - Resources and the Economy

From the earliest days, British Columbians have relied for their livelihood on the resources of the land and sea. This was true of the Aboriginal people, just as it was true of later settlers. Fish, timber and minerals were three of the province's richest resources. They became the foundation of British Columbia's wealth.

HARVEST FROM THE SEA

For hundreds of years, the First People of British Columbia relied on fish for their livelihood. It is no surprise that when the new settlers moved into the province they recognized the value of the fishery, not only for their own use but also as a resource that could be sold to customers around the world.

Before salmon could be shipped to other countries for sale, a way had to be found to keep it fresh. Otherwise, it would rot before it reached market. The Hudson's Bay Company made the first attempt to export fish. The company bought salmon from Aboriginal fishers, then salted it in barrels for shipment to Hawaii.

In the 1870s, canning was introduced. Fish packed in cans could be cooked to last a long time and was easy to handle for export. Many canneries went into operation at the mouth of the Fraser River, then all along the coast to the north. By the 1920s, there were more than 50 canneries operating along the coast of British Columbia.

Related Links: A Turbulent Industry: Fishing In British Columbia

INSIDE THE CANNERY

Canneries were huge factories where hundreds of people worked. The fish were gutted, cleaned and chopped up at long tables. Using a razor-sharp knife, a skilled butcher could process 2,000 salmon during a 10-hour workday.

Meanwhile, other crews made the cans from sheets of tin. The cans were filled with pieces of fish, soldered shut, then heated in huge pressure cookers to cook the contents. Afterwards, labels were pasted on the cans and they were packed in cases ready for shipping.

FAST FACTUsing a razor-sharp knife, a skilled butcher could process 2,000 salmon during a 10-hour workday. |

Salmon from British Columbia ended up in kitchens around the world as far away as Great Britain and Australia. Sockeye in particular was popular with consumers who loved its rich, red colour and delicious taste.

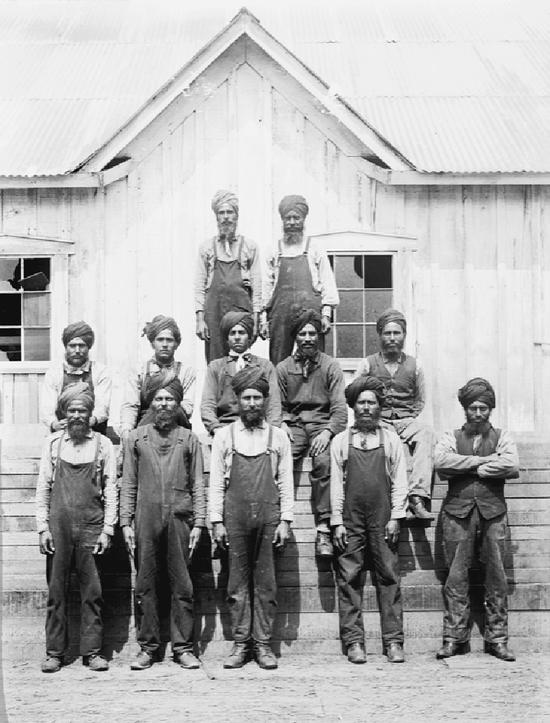

The fishery was a vast United Nations of people from different backgrounds. Many of the fishers were Japanese or Aboriginal people. Inside the cannery, the workers were mainly Chinese and Aboriginal women. Children also worked in the canneries doing menial jobs.

Canneries were only open during the summer salmon season, from about May to October. At this time Aboriginal people came from all over the coast to settle at the canneries. Families lived in separate cabins or camps, called rancheries. The Chinese lived in their own bunkhouses, known as Chinahouses, where each worker had a small cubicle with a bed and a table. When the canning season ended, Aboriginal workers returned to their villages, while the Chinese found other kinds of work as farm labourers, mill hands, miners or storekeepers.

|

BC People WEST COAST BOYHOODEarl Maquinna George grew up in the village of Ahousat on the west coast of Vancouver Island, a member of the Nuu-chah-nulth people. When he was a young boy, his parents traveled in the summer up the coast to Rivers Inlet to work in the salmon canneries. They took young Earl along with them. “We reached Rivers Inlet with 300 or 400 other boats that were going fishing like we were, “ he recalled. “A lot of them had men and women and children who were going to work in the cannery.” Just 12 years of age, Earl was hired to work in the cannery. It was his first experience on the job. He carried baskets of empty cans to the women who filled them with salmon. He was paid 13 cents an hour, and sometimes had to work 17 hours a day. Meanwhile, his father and his younger brother went fishing. The family stayed in Rivers Inlet for the fishing season, then returned home with their earnings. This is how many First Nations families made a living on the coast. |

Related Links:

Gulf of Georgia Cannery

Salmon Label Art

Canned history

FISHING FOR A LIVING

Each cannery was supplied with fish by its own fleet of fish boats. These boats dropped their nets at the mouths of the rivers to catch the salmon as they passed in the millions upriver to spawn. During the day, scows came from the canneries to collect the fish that had been caught. The earliest fishers used sails and oars, so they could not venture far from the cannery. With the addition of gasoline motors, boats were able to go farther offshore.

Fishers used three different techniques for making their catch. Some boats used gill nets. These are mesh nets with weights at the bottom and cork floats along the top so that they hang in the water like a wall. Fish swimming into the net get their gills entangled in the mesh and cannot escape. In the early days nets were hauled back into the boat by hand, a backbreaking job.

Other boats were seiners. They used larger nets that were played out behind the boat in a circle. When the circle was closed, the bottom of the net was tightened to form a bag, or purse. Any fish caught within the circle could not escape.

The third method was called trolling. Instead of nets, trollers used a series of lines, each set with several baited hooks. Boats dragged several lines at once slowly through the water, waiting for the fish to strike.

Today, gillnetting, seining and trolling are still the three main techniques used by fishers on the Pacific coast.

|

BC Places STEVESTONThe centre of the canning industry was Steveston, a community at the mouth of the Fraser River. It was known as the Sockeye Capital of the World. A visitor in 1901 described the town: “There are twenty-nine canneries at this queer town of plank streets, wooden houses and big canneries that straggle all along the river front. It is alive and kicking for two or three months in the year—the rest of the time it sleeps, and the visitor wanders through deserted thoroughfares and shut-up canneries.”

This photograph shows the canneries lining the waterfront at Steveston in about 1913. BC Archives E-00091

|

|

In Their Own Words CANOES ARRIVINGAs a teenage boy, Edwin DeBeck would watch the Aboriginal workers arrive at the canneries at Steveston, south of Vancouver. “Well here they come on a flood tide in the late afternoon bowling along ahead of a westerly wind. Great canoes 50 feet [15 m] and over, each with 4 sails. Some came all the way from the Skeena and the Queen Charlottes. They came in a flotilla, about 12 of the big ones and an equal number of lesser ones about 40 feet [12 m] or a little less. I'm sure one of the big canoes could hold up to 100 if you counted children but did not count dogs... There was considerable ceremony to the landing. A few hundred yards out sails were lowered and they started singing Indian songs until they got close to the wharf. With a final shout a sudden silence. Dead silence for about a minute. Then the biggest chief stood and with a speaking staff in his hand made a short speech. A sudden stop. A barked order. And then all hell broke loose. Everyone seemed to be rushing here and there.” |

ANOTHER RAILWAY TO THE SEA

In April 1912, one of the worst shipping disasters in history took place in the North Atlantic Ocean. The giant liner Titanic, on its first voyage out of England on the way to New York, struck an iceberg. The Titanic was supposed to be unsinkable, but the berg smashed a hole in its steel hull and the vessel sank. There were not enough lifeboats to hold all of the 2,200 people on board. More than 1,500 passengers drowned.

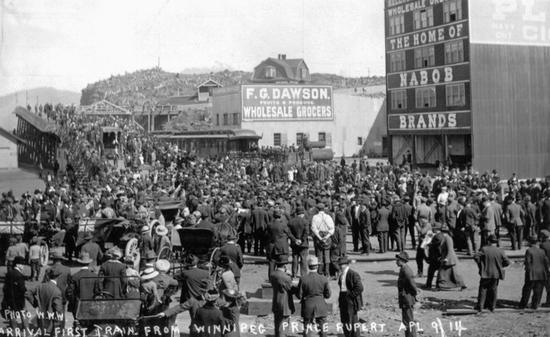

One of the victims of the Titanic disaster was Charles Hays, a railway executive in Canada. Hays was president of the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway (GTPR), a company that was building a second rail line across Canada to the Pacific. The GTPR crossed the Great Plains in the north and took the Yellowhead Pass through the Rocky Mountains into BC. Then it wound across the centre of the province and down the valley of the Skeena River until it arrived at the brand new city of Prince Rupert on the coast.

Hays had great plans for Prince Rupert. He foresaw the day when it would become a major seaport with ships arriving from around the world. Some say Hays' dreams went down with him on the Titanic. Prince Rupert did not develop the way he had hoped. The GTPR, completed in 1914, soon went bankrupt and had to be rescued by the government. However, the rail line did provide access to and from the north-central part of the province. And many interior communities owe their origins to the coming of the Grand Trunk Pacific.

|

BC Creatures THE STORY OF SALMON

The early fishing industry in British Columbia depended on the salmon. This was the most popular fish with consumers in Eastern Canada and Europe. Salmon are born, or spawned, in the rivers and lakes of the interior of British Columbia. As the young fish grow in size, they migrate down the waterways to the Pacific Ocean where they adapt to life in salt water. For several years they wander far and wide across the Pacific. When it is time for them to give birth, they return to the fresh water places where they began. By a miracle of nature, each fish finds its way back to the exact same stream where it was born. There it completes the cycle by producing its own young, then dying.There are five different types of Pacific salmon: coho, sockeye, chum, chinook and pink. Each is slightly different in appearance; each has slightly different life habits. But all of them return to the rivers to spawn. |

DISAPPEARING FISH

In the early years, there were so many salmon that it seemed as if they would last forever. Nobody gave any thought to preserving their numbers. Vast quantities were wasted every year. But still the fish returned to the rivers.

Then, disaster struck. Up the Fraser River there is a narrow gorge known as Hell's Gate. Here the fish fought their way up the rapids to reach their spawning grounds in the interior. In 1913, railway builders were laying track beside the river through Hell's Gate. Blasting caused rock slides into the river, making it impossible for the fish to pass. Millions of fish died, unable to spawn. It was 30 years before the damage was repaired. Even then the Fraser never again produced as many salmon as it did before the slides.

The fishers and the cannery owners soon realized that steps had to be taken to slow down the slaughter. They wanted to keep on profiting from the fishery. Many jobs relied on the canneries. However, they also realized that if the salmon disappeared, there would be no industry at all. The history of the salmon fishery ever since has been an attempt to balance the needs of the industry with the long-term survival of the fish.

Related Links: Fish Passage Structures on the Fraser River

TALL TIMBER

Another important resource from British Columbia was wood. Most of the province was cloaked in thick forests of tall timber. Visitors were over-awed by the size of the trees. “We are pygmies among the giant pines and cedars of this country,” wrote the explorer David Thompson.

Aboriginal people made the tall trees into totem poles, canoes and planks for their cedar houses. Later, the British navy used them for masts for their sailing vessels. Then, as settlers moved into the province in greater numbers, the demand for lumber increased. Everything was made of wood in those days: houses, ships, buildings of all types, even sidewalks.

Related Links: Big Trees on Salt Spring Island

WORKING IN THE WOODS

Logging began first along the coast where timber grew especially tall. Loggers felled the trees on the steep slopes, then rolled them down into the water. They were called handloggers because they had no machinery; everything was done by muscle power. Where land was flat, logs were hauled to the water by teams of horses or oxen. Floating logs were joined together in large rafts, called booms, and towed down the coast to the nearest sawmill for cutting into lumber.

The arrival of the railway made a big difference to the loggers. Track was laid into the woods and special logging railways carried logs to the water, or directly to the mills. Railways also opened up the interior so that logging spread throughout the province.

One important market for British Columbia wood was the Canadian Prairies. After 1900, hundreds of thousands of new immigrants arrived in the Prairie West to homestead farms.

The railway connected the Pacific Coast across the mountains to this expanding region where there was a huge demand for lumber.

|

In Their Own Words DAVID THOMPSONThe explorer David Thompson wrote: “We are pygmies among the giant pines and cedars of this country.” |

|

In Their Own Words A LOGGER'S DAYAn early handlogger described the daily routine in one of the coastal camps about 1900: "The first morning light would see them already at their place of work, perhaps a mile’s rowboat journey from their home. There they would slave all day; carrying their sharp, awkward tools up through the hillside underbrush; chopping and sawing, felling big timber; cutting up logs, barking them; using their heavy jackscrews to coax logs downhill to the sea. At evening, they would tow such logs as they had floated round to their boom, and put the logs inside, in safety. Then they could go home and dry their clothes, and cook supper, and sleep like dead men." From Woodsmen of the West, M.A. Grainger (Arnold, 1908), p. 53.

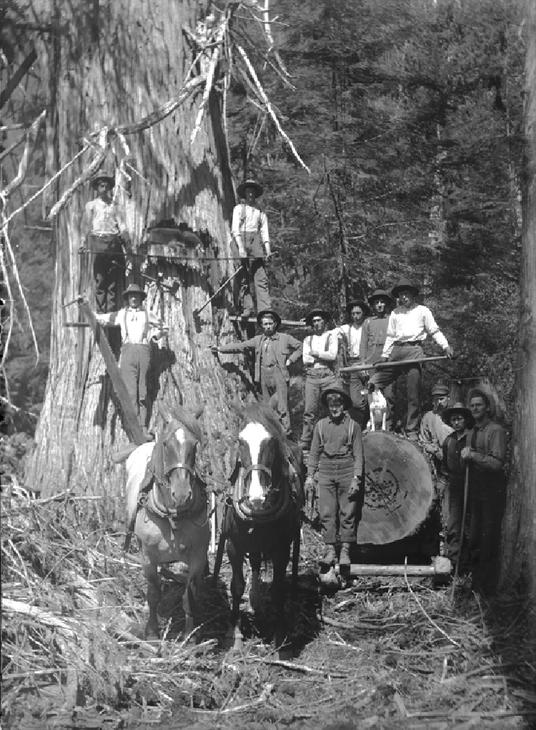

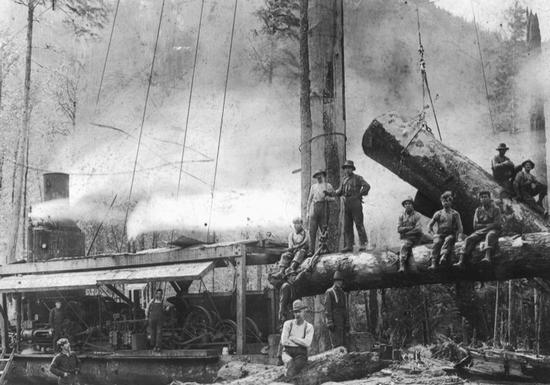

A logging crew at work in the woods in 1911. By this time, steam power was being used. The large engine at left was known as a donkey engine. It powered gears and winches, which operated the wire ropes that hauled the heavy logs out of the underbrush where they fell. BC Archives E-04615

|

|

BC People FRENCH IN THE WESTFrench-speaking people from Quebec have lived in British Columbia ever since the days of the fur trade. Most of the voyageurs returned to Quebec when their tour of duty in the West ended, but a few remained and became British Columbia’s first French residents. The logging industry brought another influx of French speakers. In 1909, a sawmill owner in New Westminster imported 150 workers from Quebec to operate his mill. Logging was an important activity in Quebec as well, and the owner knew that he would be getting experienced workers. The Quebec workers settled together in houses north of the mill. Others followed, and pretty soon there was a French-speaking community of families centred around a Catholic church. It took its name from the priest, Edmond Maillard. Today many more French-speaking people live all over British Columbia, but the pioneering community of Maillardville (ma -LARD-vill) still keeps its French character. |

FAST FACTAbout 55,000 people in BC speak French as their first language. |

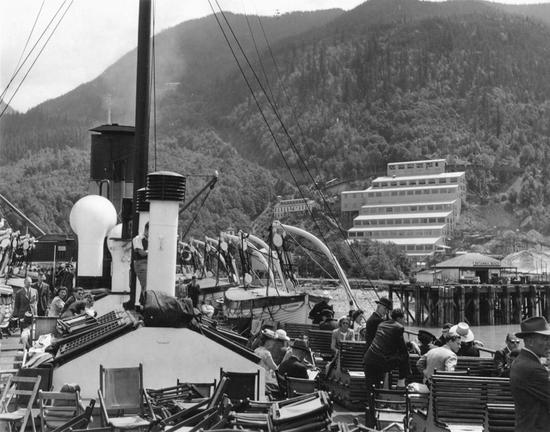

UNION STEAMERS

Along the coast of British Columbia, people lived at canneries and in small fishing and logging camps. There were no roads. Coast dwellers relied on boats to bring in their supplies and keep them in touch with the outside world.

These boats belonged to the fleet of the Union Steamship Company. The company was created in Vancouver in 1889. Before long its fleet of steamers were cruising the coast all the way north as far as Prince Rupert.

Boat day, the day the Union steamer arrived, was an exciting time for the people who inhabited these isolated communities. “Old and young live, wait and listen for that ship's shrill whistle,” wrote one pioneer. “It means our food supplies, mail, familiar faces returning home. On boat days our children are restless at school, coaxing their teacher to let them go down to the wharf to watch the ship come sliding in.”

Union steamers operated on the coast until the 1950s. By then most of the logging camps and fish canneries had closed and the steamers were replaced by more modern car ferries.

|

In Their Own Words BOAT DAYBoat day, the day the Union steamer arrived, was an exciting time for the people who inhabited these isolated communities. One pioneer wrote: "Old and young live, wait and listen for that ship’s shrill whistle. It means our food supplies, mail, familiar faces returning home. On boat days our children are restless at school, coaxing their teacher to let them go down to the wharf to watch the ship come sliding in."

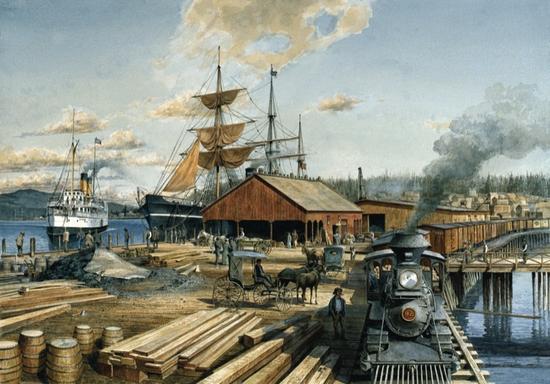

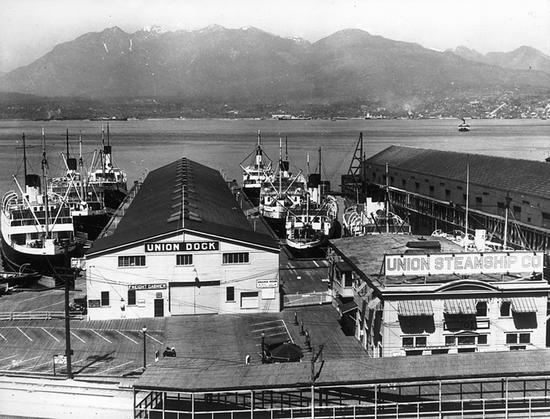

The Union Steamship dock in Vancouver, headquarters of the coastal fleet. Leonard Frank photo, City of Vancouver Archives CVA Wat.P83

|

COAL WAS KING

British Columbia's third important resource industry was mining. Gold was the most important mineral in the early days. It was gold, after all, that led to the creation of British Columbia. But most of the gold soon disappeared, and coal became the most important mineral in the province.

Coal was like black gold. It was extremely valuable as a fuel to drive the steam machinery of the industrial age, whether it was the blast furnaces in the factories or the steam engines on the transcontinental railways. One steady customer for British Columbia coal was the British navy who used it to fuel their warships patrolling the Pacific.

Nanaimo on Vancouver Island became the centre of coal mining. The town itself sat on a giant coal field and mine shafts formed a network of underground passages beneath the ground. Some tunnels even ran out under the harbour.

|

In Their Own Words BOY MINERSBoys as young as thirteen years old worked in the coal mines. Usually they worked above ground, looking after the equipment or sorting the coal that came up from below. But many youngsters worked down below as well, eager to earn the higher wages paid to underground workers. One old-timer remembered: "Well, when you were a boy that was all there was around here them days. That’s all we had to look forward to. They couldn’t keep me out of the mines. I was bred a coal miner. My father was diggin’ coal when he was eleven. He worked in the mines all his life. I left school of my own accord to work in the mines. They wanted me to keep going to school but I said,“No dice!” I was 15 years old then and like father like son. Anyway, I had a lot of chums that was workin’ in the mines and my mother needed the money. The mines was the only thing there was in those days." From Boss Whistle, Lynne Bowen (Oolichan Books, 1982), p. 58.

Young workers at the entrance of the Nanaimo coal mine shaft around 1870. British Columbia Archives C-03710

|

TROUBLE UNDERGROUND

Coal mining was very dangerous work. It was not unusual for the walls of the tunnels to collapse, trapping the miners underground or burying them alive. Poisonous gases built up in the mines and a stray spark could ignite them in deadly explosions. On one occasion in 1887, an explosion in a Nanaimo mine killed 148 miners. Owners, anxious to make profits, did not always take the safety precautions they should.

Workers wanting higher wages and safer working conditions formed unions and went on strike. The longest conflict began in 1912 when Vancouver Island miners walked away from the mines and did not return to work for two years. Mine owners evicted the strikers from their homes and brought in replacement workers to keep the mines open. The government sent in soldiers to prevent violence. It was one of the worst periods of labour unrest in British Columbia history.

THE KOOTENAY MINING BOOM

Coal was not the only mineral mined in British Columbia. Starting in the 1880s, prospectors discovered a series of rich deposits in the southeast corner of the province in an area known as the Kootenays.

The Kootenays was a region of high mountains, beautiful lakes and narrow river valleys. It was far from the main cities and difficult to reach. But once rail lines were built and paddlewheel steamboats cruised the lakes, it became possible to start mining the plentiful supplies of silver, lead, copper and zinc.

Some of the richest mines in the world were in the Kootenays. The Sullivan mine at Kimberley was the largest lead-zinc mine in the world. It is still in operation. Silver was discovered at the Silver King mine near the city of Nelson, and gold at the LeRoi mine at Rossland. More than half of all the copper produced in Canada came from British Columbia. At Trail, the mine owners opened a huge smelter to separate the precious metals from the ore in which they were found. A whole new area of British Columbia was suddenly alive with activity.

|

BC Places THE LAST STEAMBOAT

Paddlewheel steamboats operated on many of the lakes and rivers of the Interior. On Kootenay Lake, paddlewheelers were active from the 1880s. They were an important link in the transport system that carried supplies and workers to the isolated mines. The last steamboat to operate in Canada was the SS Moyie, which ran on Kootenay Lake from 1898 to 1957. It is the oldest sternwheel paddleboat still in existence anywhere in the world. The Moyie was rescued from oblivion when it retired, and it is berthed on the waterfront in the town of Kaslo. It is an official historic site and visitors are welcome to go on board. |

Related Links:

Upper Kootenay River Sternwheelers

Living Landscapes: Columbia Basin

Mining in BC Information

Of Interest to Teachers:

Mineral Resources Education Program: Teacher Resources

A NEW ECONOMY

Railways opened up the interior of British Columbia and connected the province to markets in the rest of the continent. Trains carried timber, minerals and fish across the Rockies, and returned with grain and other products. Railways spread into isolated parts of the province, making possible new mining and logging ventures.

Once British Columbia had relied for its prosperity on a single product: first it was fur, then gold. Now a variety of different industries developed. Salmon canneries opened on the coast. Logging camps and sawmills spread through the forests. New mines produced coal and other minerals.

Between 1881 and 1921, the population of British Columbia increased by over ten times. Most of these newcomers got jobs in the new mines, mills, farms and logging camps. The province was no longer a pioneer outpost. It had entered the modern industrial era.