Chapter 8 - Boom Times

With the end of the Second World War, British Columbia entered a period of economic expansion. A new railway reached into the North. New mines, highways, dams and mills were built. At the same time, many of the barriers that once divided different groups began to come down. First Nations people and newcomers from Asia and other parts of the world took a greater role in society.

TIME FOR A CHANGE

At the end of the Second World War, British Columbians decided it was time for a change. During the war, the two major political parties — the Liberals and the Conservatives — had formed a coalition. Together they had run the government for many years. With the emergency of war over, the partnership began to come apart. A new force emerged on the political scene.

|

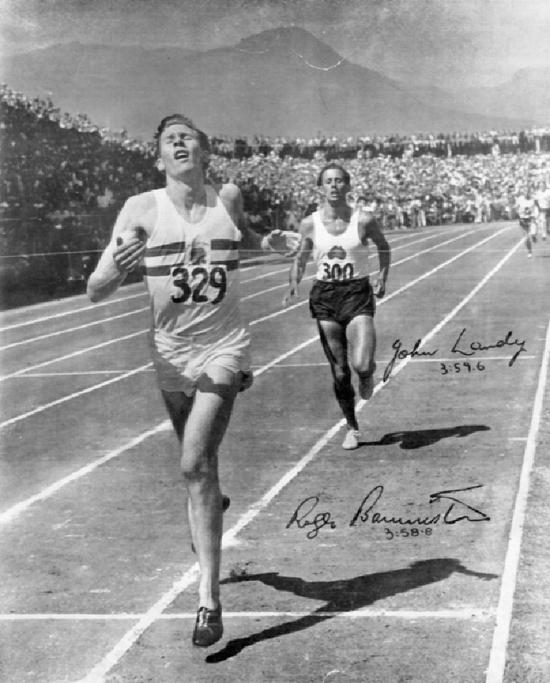

BC Spotlight THE MIRACLE MILEThe photograph at the start of this chapter shows the finish of the “Miracle Mile” at the British Empire Games in Vancouver in 1954. It was a “miracle” because for the first time two athletes ran a mile in under 4 minutes in the same race. The photograph shows Roger Bannister of Britain crossing the finish line less than one second ahead of Australia’s John Landy. It was the first international sporting event shown live on television across North America. And it was the lead article in the first issue of Sports Illustrated magazine. Often forgotten is another runner, BC’s own Bill Parnell, who held the mile record for the Empire Games before Bannister and Landy broke it. |

SOCIAL CREDIT

The new force was called Social Credit. It was a new political party, formed early in the 1950s. Its leader was W.A.C. Bennett, a hardware store owner from Kelowna. In the 1952 election, Social Credit won one more seat than the CCF and formed a new government. W.A.C. Bennett became premier, a job he held for the next 20 years, longer than anyone else in BC history.

Bennett was a born salesperson. He was full of energy and loved to give long speeches. More than that, he liked to get things done. His rivals called him “Wacky”, but “Wily” would have been a better nickname. He was a clever politician who seemed to understand exactly what the voters wanted.

Bennett's government embarked on a massive building program. New highways spread through the interior. New bridges spanned the rivers. Social Credit opened universities in Burnaby and Victoria, built a railway to the north, and created a fleet of coastal ferries. At times it seemed as if the whole province was under construction.

DAM BUILDER

Premier Bennett needed a way to pay for all this development. He believed he found the way with the construction of large hydroelectric dams. Hydroelectricity is electricity produced by water. A dam blocks the flow of water in a river to create a large lake, or reservoir. As the water flows out of the reservoir, it is transformed into electrical energy by a giant machine called a turbine. The electricity that is produced is used in homes and as a fuel for industry.

In 1961, Bennett took over a private electrical company and created BC Hydro, a government agency. BC Hydro went to work building huge dams on the Columbia River in the south and the Peace River in the North. Vast areas of land were flooded to create reservoirs behind the dams. One of the dams, named for Premier Bennett, created Williston Lake, the largest lake in BC. The underground powerhouse was the largest in the world when it opened in 1968. Another, the Mica Dam, stands as tall as an 80-storey building. The electricity produced by these dams fuelled the growth of British Columbia. Whatever was left over was sold in the United States.

THE LITTLE RAILWAY THAT GREW

Another Social Credit project was British Columbia's own railway, the Pacific Great Eastern. The idea was to connect the south coast with the northern interior. Construction began on this railway long before Premier Bennett came to power. But work went slowly, and the line went bankrupt after laying just a few kilometres of track.

People made fun of the little railway that seemed to go from nowhere to nowhere. They called it the Please Go Easy, or the Prince George Eventually. The government took control of the line, but still not much work was done.

Premier Bennett's government realized how important the railway could be. It finally completed the work from North Vancouver all the way to Fort St John and Fort Nelson, two towns in the far northeast corner of the province. By 1971, the remote north had its first rail connection to the coast. Coal, wheat and other products began flowing south by train. The railway played an important part in tying together the different parts of the province.

Today the PGE is called BC Rail. It operates more than 2,000 km of track. Along with freight, it carries travelers from North Vancouver to Prince George through some of the most beautiful landscape in Canada.

RESOURCE TOWNS

The end of the war brought a great demand for British Columbia's resources. Minerals and timber were needed to build homes and fuel factories across Canada and around the world.

Many of the mines and logging camps were located in remote parts of the province, far from the main cities. Companies created instant towns for their workers to live in.

One such town was Kitimat. Early in the 1950s the Aluminum Company of Canada (Alcan) chose to build a smelter at the head of Douglas Channel far up the north coast. An aluminum smelter is a large plant where ore called bauxite is melted down to produce aluminum metal. This process requires a lot of electrical power, and there was a good source of power near the Douglas Channel site. Alcan called the smelter, and the town it built to house the workers, Kitimat, named for the local First Nations people.

Bauxite was brought to Kitimat by freighter from mines in Jamaica, Guyana and Australia. After processing, the refined aluminum was shipped to customers around the world. Today about 11,000 people live in Kitimat, mostly working for the Alcan smelter.

Another resource town on the north coast was Ocean Falls. It was the site of a large pulp and paper mill that operated on electricity produced from a waterfall nearby.

Ocean Falls was the rainiest community in Canada. It was known for producing world-class swimmers, as well as pulp and paper. At its peak, the population was about 4,000 people. Then the mill closed. Without work, people had to move away. Today hardly anyone lives where Ocean Falls used to be.

Instant towns were not all on the coast. Mackenzie is located in the Interior close to the Rocky Mountains. It was created in 1966 when logging companies began operations in the surrounding forests. Mackenzie has two pulp mills, a mill that produces newsprint (the kind of paper used to print newspapers) and several sawmills. The town, with a population of 6,000, is named for the explorer Alexander Mackenzie.

THE NORTHEAST

The northeast corner of British Columbia is especially rich in natural resources. During the 1950s large amounts of oil and natural gas were discovered in this area. These two fuels run the machinery of industry, produce heat for our homes and drive our cars. Oil and gas are both found in pools deep under the ground. Crews dig wells to tap into these pools and bring the oil and gas to the surface. Then it is carried in pipe lines to the large cities where it is needed.

Fort St John is the centre of this industry. It is located on the Alaska Highway and calls itself the Energy Capital of BC. The Peace River flows eastward through this corner of the province into Alberta, so it is often called the Peace River Country.

Coal is another valuable resource that comes from the Northeast. The town of Tumbler Ridge sprang to life in 1981 to provide homes for mining families from two huge coalmines that opened nearby. Much of the coal that was mined at Tumbler Ridge was sold in Japan.

Related Links:

Living Landscapes: Peace River - Northern Rockies

|

BC People NANCY GREENENancy Greene grew up in Rossland, one of the resource towns of the Interior. She began skiing as a youngster on nearby Red Mountain. When Greene was seventeen years old she joined Canada’s national ski team and began racing in competitions in Europe and the United States. By 1967 she was one of the best skiers in the world. At the 1968 Olympics she won a gold medal in the giant slalom race and a silver medal in the slalom. No wonder she was named Canada’s Athlete of the Year. Today, Nancy Greene and her husband manage a ski resort near Kamloops, BC.

Nancy Greene, centre, won a gold and a silver medal at the 1968 Grenoble Winter Olympics. BC Sports Hall of Fame

|

A SOCIETY OF MANY CULTURES

Following the Second World War, the Japanese Canadians who had been sent away from the coast were allowed to return. British Columbians came to realize that they had to become more open to people of different cultural backgrounds.

In 1947, people of Asian background were allowed the vote in elections. Then, in the 1960s, limits on the number of immigrants from Asian countries began to be relaxed. Since that time, British Columbia's population has become much more diverse as people have come to live here from many parts of the world. This is what is meant when BC is described as a multicultural society.

One sign of the different attitude was the arrival of the “boat people” in the 1970s. They were Chinese and Vietnamese refugees who fled Vietnam by boat to escape the war and the political troubles there. Many made their way to British Columbia where they were welcomed with generosity. Groups of residents got together to help the newcomers adjust to their new life.

FAST FACTAbout 7,400 “boat people” came to live in BC during this period. |

THE DOUKHOBORS

Not everyone adjusted with ease to life in British Columbia. The Doukhobors were a group of newcomers from Russia who practised their own religion. Among their ideas was a strong belief in non-violence. When the Russian government forced the Doukhobors to fight in the army, many of them left their homeland for Canada where they were promised they could live in peace.

In 1908, a group of several thousand Doukhobors settled in eastern British Columbia. They lived together in large houses and operated farms and businesses. For the most part they avoided contact with the wider society. They preferred to follow their religion and educate their children themselves.

As time went on the government began to force Doukhobor children to attend public schools. Some parents resisted, and a long period of unrest began. Schools were burned, protest marches were held and many Doukhobors were arrested. They wanted to be left alone to follow their own lifestyle. The government felt that the Doukhobors had to conform to the rules like everyone else.

Finally, in the 1960s, the protests petered out. Younger Doukhobors adjusted to life in the wider society and other British Columbians grew to accept their differences. Doukhobors still live in towns such as Grand Forks and Castlegar. Many still speak Russian, practise their religion and work to keep their traditions alive.

Related Links:

Living Landscapes: The Doukhobors

|

BC People KEEPING THE WORLD GREEN

Greenpeace members erect a wind farm on the lawn of the BC Legislature to bring attention to renewable forms of energy. May 2004. Greenpeace

The organization Greenpeace has a huge army of activists fighting to stop pollution and protect wildlife around the world. But in 1970, Greenpeace was a small group of people in Vancouver who wanted to put a stop to the testing of nuclear bombs by the United States in the ocean near Alaska. These protestors hired an old skipper and his rundown fish boat, the Phyllis Cormack, and sailed north toward the test site. Their plan was to put themselves in the middle of the test site and dare the American government to blow them up. As it turned out, the boat was stopped by bad weather, and the bomb test went ahead. But the protest got so much support that the Americans agreed to stop nuclear testing. The new organization called itself Greenpeace and started a new campaign, to stop the killing of whales. They tracked down the whaling ships far out at sea and tried to shield the whales from the hunters. Once again Greenpeace attracted a lot of attention, this time to the slaughter of the whales. Due in part to their efforts, the whale hunt ceased. Today Greenpeace has headquarters in Europe and followers around the world. Not everyone approves of the tactics it uses, but Greenpeace has been very successful in drawing public attention to the destruction of the environment.

The crew of the Phyllis Cormack on a voyage to protest nuclear testing, 1971. Robert Keziere photo

|

ABORIGINAL PEOPLE

In the years following the Second World War, Aboriginal people came to be more accepted by non-Aboriginal people in British Columbia. Many First Nations people had fought for Canada in the war as soldiers and it seemed unfair to deny them equal rights. In 1951, the ban on the potlatch was ended. First Nations were now able to practice their own ceremonies without fear of going to jail. In 1960, First Nations people were given the vote in elections.

Another change that took longer to bring about was the closing of the residential schools. These schools had been in operation since the previous century. First Nations children were taken from their families and sent to live at the schools. They were not allowed to speak their own languages and they were taught that their own cultures were inferior. The purpose of the schools was to force Aboriginal people to become part of the mainstream society.

Some residential schools turned out to be terrible places. Disease was common, and many youngsters died. Some of the teachers were cruel and mistreated the children.

In the 1960s the government began to close the residential schools. The last one closed in BC in the mid-1980s. The government recognized that it was wrong to try to destroy First Nations culture.

|

BC People TOTEM POLE CARVERS

Mungo Martin, a renowned Aboriginal carver, at work on a pole in the carving shed at Thunderbird Park, at the Royal BC Museum in Victoria, 1961. BC Archives I-26829

In the 1950s and 1960s, the arts of the Aboriginal people, which had been suppressed for many years, began to revive. This was especially true of totem poles, the tall wooden monuments that stood in front of houses, graveyards and villages along the coast. In 1952, the Royal BC Museum in Victoria hired Mungo Martin, a skilled carver, to restore some of the museum’s poles. Martin belonged to the Kwakwaka’wakw (kwalk-WAH-kah-walk) people. The poles he made were put up in Thunderbird Park at the museum, where they can be visited today. Martin also built a traditional longhouse at the site. Mungo Martin trained many younger carvers to follow in his footsteps. Aboriginal carvers have made some of the finest works of art produced in British Columbia. |

BENNETT TOO

No government lasts forever. After 20 years in office, W.A.C. Bennett lost the support of the voters in the 1972 election. Some people felt that he was using up the resources of the province just to remain in power. Others felt it was time to give someone else a chance at running the government.

Bennett retired from politics after his defeat. But the Social Credit Party remained in the family. His son Bill became leader, and in 1975 led the party to an election victory. Bill became premier like his father, and Social Credit began another 16 years as the government.

EXPO '86

In the summer of 1986, Vancouver turned 100 years old. The city celebrated by welcoming the world to a huge party. It was called Expo '86, and it was the first international fair ever held in British Columbia.

Expo '86 took place along the waterfront of False Creek in the middle of downtown. False Creek was once the site of sawmills, lumber yards and factories. It was made over for the fair to become a bustling centre of pavilions, restaurants, plazas and thrill rides.

FAST FACTForty-one countries took part, along with 20 million visitors. |

Expo '86 brought a surge of tourism to the province. After the fair was over and the visitors went home, Vancouver was left with a new transit system and many new buildings. The site of Expo was sold and the fairground was replaced by highrise condominiums.

The fair seemed to express a new confidence in the city, and the province. British Columbians were happy to be the centre of the world's attention. They were proud to show off what the years of prosperity had accomplished.