Chapter 9 - Modern Times

History is the study of the past. It tells us how people used to live in times before our own. History also tells us about the present. It tells us how the world we live in came to be the way it is. Not only that, history can prepare us for the future. By helping us to understand how things changed in the past, it helps get us ready to deal with changes yet to come. Change brings new challenges. As the world becomes different, we have to adapt to new situations. What are some of the important changes that are happening in British Columbia today, and how are people in British Columbia responding to them?

A LONG, HOT SUMMER

Clayoquot (pronounced Clay-kwat) Sound is a wilderness area of islands, beach and forest on the west coast of Vancouver Island. It is in the territory of the Nuu-chah-nulth people. Its unspoiled beauty attracts whale watchers, hikers, kayakers and other kinds of outdoor adventurers.

In the summer of 1993, another type of visitor arrived in Clayoquot. They were protesters who were angry that loggers were allowed to cut trees in the river valleys running into the Sound. The protesters set up blockades across the dirt roads and would not let the logging trucks pass.

Loggers asked the courts to open the roads so they could do their work. Police arrested more than 900 protesters during the summer. It was the largest number of people arrested at one time in Canadian history. Some had to pay fines; others received time in prison. As a result of the summer of protest, the government made stricter rules for logging companies in Clayoquot. As well, some of the companies promised to make changes so that logging would be less damaging to the landscape.

SAVING THE FORESTS

The Clayoquot protest was one of many taking place in the forests of British Columbia during the 1990s. For years logging had been a mainstay of the province's economy, producing jobs and income for many people. But as more and more of the forest disappeared, people began to worry that soon it would all be gone. What would be left for their children and grandchildren to enjoy?

Protests also stopped a copper mine near the Tatshenshini River in the far north of the province. The “Tat” is one of the best places in the world for seeing grizzly bears and other wild animals. Scientists worried that the mine might destroy the habitat where the bears lived. In response, the provincial government created a provincial park to protect some of the watershed.

Meanwhile, the salmon also seemed to be in danger of disappearing. For decades the fishing fleet had harvested these valuable fish as they made their way back to the rivers and streams to spawn. But during the 1990s the numbers of salmon dropped. The government stepped in to set a limit on the number fishers were allowed to catch. Many people predicted that salmon fishing would have to stop completely to allow the fish time to recover.

British Columbians have always relied on their natural resources to produce wealth. But natural resources do not last forever. The quest for wealth may lead to their destruction. If resources are not preserved, they will be used up and there will be nothing left for future generations.

In the 1990s more and more people began talking about sustainable development. Instead of using up all the resources, sustainable development says that we must replace the resources at the same rate at which we are using them. In this way, we leave something for future generations to enjoy. And if certain resources cannot be replaced, then we must find ways to preserve them.

The challenge faced by British Columbians is to maintain a decent level of wealth without at the same time destroying the natural resources which were once so plentiful.

FARMING FISH

Since the 1980s, fish farms—mainly salmon farms—have opened in sheltered waters along the coast of British Columbia. The farms are floating cages inside which salmon are raised until they are large enough to sell to stores and restaurants.

Supporters of salmon farming say that it is better to grow our own fish than to use up stocks of wild salmon. They compare fish farming to raising chickens or beef cattle and say that it is just as safe.

Critics of fish farming worry that diseases will spread from the farmed fish to wild fish, and that sewage from the farms will pollute coastal waters. They also worry about the impact of fish farming on the livelihood of people who catch wild fish for a living.

Fish farming is a young industry and no one knows for sure what long-term impact it will have on the ocean. Meanwhile, farms raise thousands of tonnes of salmon each year, which is sold in markets and stores alongside fish caught in the wild.

FAST FACTIn 2004, fishers in British Columbia caught 25,566 tonnes of wild salmon. In the same year, BC fish farms produced 61,800 tonnes of salmon. |

|

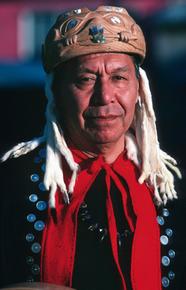

BC People

|

MAKING TREATIES WITH THE FIRST NATIONS

When Europeans first arrived in British Columbia, they found many different First Nations groups living here. Gradually the newcomers took over the land, forcing the First Nations to live apart on small plots of land called reserves.

In the prairie provinces and in most of eastern Canada, the First Nations signed treaties with the government. They gave up their land in return for reserves, money and other benefits. In British Columbia, however, only a very few First Nations made treaties with the government. The rest have no treaties.

The government argued that First Nations in British Columbia had no rights to their lands. On their side, First Nations argued that they had never given up their territories. The courts ruled several times in favour of the First Nations. As a result, in 1993, the BC government agreed to discuss treaties. It set up a BC Treaty Commission to supervise the discussions.

It will take many years to make agreements with the First Nations. People on both sides hope that the treaty-making process will result in better relations between First Nations and other residents of British Columbia.

|

FAST FACT About 2,500 Nisga’a people live in communities along the Nass River. |

|

In Their Own Words

Gary Fiegehen photo

|

|

BC People THE NISGA'A AGREEMENTThe Nisga’a people live in the valley of the Nass River in northern British Columbia. They consider this territory to be their homeland. For one hundred years they refused to give up this claim. In 1973, the Supreme Court of Canada made a ruling in favour of the Nisga’a. Because of the court, the federal government agreed to begin negotiations. The BC provincial government also agreed to take part, and the result was a historic agreement signed in 1998. The Nisga’a agreement gave the Nisga’a people $190 million, more than 2,000 square kilometres of land in the Nass Valley, a share of the salmon from the river and other benefits. Many other First Nations are negotiating with the government to have their own agreements for their own territories. |

A MULTICULTURAL SOCIETY

During the 1990s, the population of British Columbia grew faster than any other province in Canada. Most of the growth was the result of immigration, the arrival of newcomers from other places. Immigrants had been coming to British Columbia ever since the beginning. The difference was that in the 1990s, most of the newcomers came from countries in Asia.

As a result of immigration, by the end of the 1990s about 20 percent, or one in five, of British Columbians came from Asia, places like Hong Kong, China, India and Japan. Most of the newcomers lived in Vancouver and the surrounding area. By 2001, there were as many people for whom English was a second language as there were people who spoke English at home. In some neighbourhoods, there were as many as 80 different languages spoken.

FAST FACTAfter English, more people in BC speak Chinese than any other language. |

This is news because British Columbia has always considered itself a “British” province, as its name suggests. For a long time most of the people living here came from Great Britain, the United States or eastern Canada. They had always considered themselves the majority. Now statistics were showing that British Columbia was a very multicultural province.

Of course, British Columbia has always been a mix of people from different backgrounds. Chinese miners and railway workers, Japanese farmers and fishers, mill workers from India, Black homesteaders, Doukhobor settlers from Russia, all these and many others have been part of the society. However, since the 1960s, many more people from Asia, Africa and the Caribbean came to live in BC. In the process they created a very mixed society of people from many backgrounds.

A multicultural society is a society where people of many different backgrounds live together. The differences create variety and interest. Sometimes they also create misunderstanding and conflict. People from different backgrounds with different beliefs may find it difficult to get along with one another.

The challenge for British Columbians is to create a society where everyone feels they are able to participate, where no one is held back by the colour of their skin, what religious beliefs they have or where they come from.

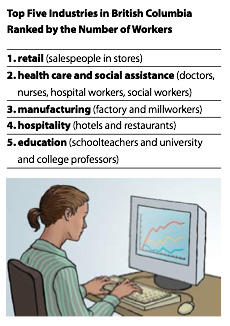

THE MODERN ECONOMY

The economy of British Columbia has changed dramatically during the past decades. The economy used to rely on producing natural products: timber, minerals and fish. These are still important, but less so than they once were.

Today, many more jobs are in the knowledge industries. These are jobs that make and share information. Examples are computer programmers, medical researchers, and engineers. These people do not catch fish, or cut down trees, or dig up minerals. Instead, they work with information to produce new products.

The number of jobs in the resource industries are dropping. This is because the resources themselves are becoming more scarce. It is also because machines are doing much of the work once done by people. Mills need far fewer workers to produce their lumber. As stocks of fish appear to be in decline, far fewer fishers are needed to bring in the catch. The question is: will there be new jobs to replace the ones that are lost?

The challenge for British Columbians is to adjust to the new economy. New jobs have to be found for young people just entering the workforce. And many people who were fishers, loggers or miners will have to learn jobs for the new industries.

FAST FACTFarming, fishing, logging and mining still produce about three-quarters of all the goods that BC sells to other places. But less than 10 percent of the workforce hold jobs in these industries. |

LIVEABLE CITIES

Another challenge facing British Columbia is to keep the cities liveable. Three quarters of the population of the province lives in Greater Vancouver, a huge, sprawling mass of highways and highrises. All these newcomers need somewhere to live. They need more roads to drive on, more parks to relax in, more buses to take to work, and more dumps to take care of all the garbage.

FAST FACTEvery year, 50,000 more people come to live in the city. |

Every hour two new cars are added to the traffic already crowding Vancouver's streets. This makes it harder to move around the city. It also means that the air is getting dirtier and harder to breathe.

Air pollution is just one of the problems caused by rapid growth. Another is the disappearance of green spaces — park and farm land that is gobbled up to build houses for the newcomers.

The challenge for British Columbians is to make room for all the newcomers, while at the same time keeping their cities clean, safe places to live.

THE OLYMPIC GAMES

On July 3, 2003, British Columbia held its breath and waited. Finally the envelope was opened and the announcement was made. The 2010 Winter Olympic Games would be taking place in Vancouver and the nearby mountain resort of Whistler.

The announcement ended five years of planning and debate. It takes a lot of preparation to host an Olympics. Sports arenas and ski hills must be built, along with housing for all the athletes who will arrive from all over the world for the 16-day event. What's more, Vancouver and Whistler will also host the Paralympic Winter Games for athletes with disabilities.

Not everyone wanted BC to host the Olympics. It will cost billions of dollars to pay for the Games, much of which will come from the government. Some people argued that the money should be spent on other, more important things. Olympic supporters argued that, in the end, the benefits will outweigh the costs.

Soon after the announcement in 2003, British Columbians were hard at work getting ready to host the 2010 Olympics. The challenge is to have everything ready on time, and to put on a good show for all the people around the world who will be watching on television.

A HISTORY OF CHALLENGES

As British Columbians begin a new century, they face important challenges.

Some of these challenges are:

• saving the natural environment from being spoiled.

• making fair agreements with the First Nations people.

• learning to live with people of different backgrounds and beliefs.

• making the cities safe, clean places to live.

• training for jobs in a new economy.

History shows us that British Columbia has always been a place where people had challenges to face. The story of the province is the story of how these challenges were met and solved.

History gives us confidence that we can meet the challenges of the present, just as our parents and their parents before them met the challenges of the past.