Chapter One: “Free negroes and other obnoxious persons”

One day in the early 1850s, a familiar White customer entered the Clay Street Pioneer Shoe and Boot Emporium run by Peter Lester and Mifflin Wistar Gibbs, two of San Francisco’s most successful Black merchants. After examining a pair of boots, the customer asked Lester to set them aside for a while, saying he wanted to think about buying them. The proprietors were glad to oblige.

A few minutes later, another White man, a friend of the first, came in and tried the same boots on. He insisted on buying them. When Lester and Gibbs tried to explain that the boots were being kept for his friend, the man assured them that he would personally explain the matter; then he left the store.

Very shortly afterward, the two merchants found that a brutal joke was being played on them. Both White men entered the store. The first one pretended to be furious over the sale of the boots and swore viciously at Lester. While the Black men tried to explain, the first customer struck savagely at Lester with his cane. Neither Lester nor Gibbs dared to resist; both White men were armed, and no one else was in the store.

After beating Lester bloody, the White men left, serene in the knowledge that their victim had no hope of redress: under California law, no Black person could testify in court against a White man.

But Gibbs could recall the incident half a century later in his autobiography, Shadow and Light, and it was clearly a critical moment—not only for him and his business partner, but also for their community and for Canada, a country that did not yet exist.

San Francisco in the 1850s was a gold rush town where murder was commonplace, so the beating of a Black man might have seemed trivial, a normal hazard of doing business. Added to other incidents, however, the beating helped to start one of the most remarkable yet little-known mass migrations in the history of North America. After a decade of beatings, insults and legalized injustice, some six hundred Black Californians would migrate north to the British colony of Vancouver Island and to the goldfields of the mainland of what is now British Columbia. Their story was to be one of triumph and betrayal, of bitter humiliation and quiet success. The Black immigrants would affect the course of Canadian history; in fact, by helping to save British Columbia from American annexation, they helped to ensure that Canada itself would maintain its independence of the United States.

The Black pioneers’ experience in the rough, rich, bizarre Northwest would foreshadow that of later immigrants, including the deserters and war resisters of the 1960s and Ugandan Ismailis of the 1970s. And while the Black residents were to be used as political pawns by some of British Columbia’s rulers, some Black citizens in turn would use BC as a stepping stone to greater things.

As Lester and Gibbs cleaned themselves up in their disordered shop, however, they were not yet thinking of escape. Intelligent, educated and idealistic, they were already—in their early thirties—veterans of the struggle to abolish slavery and improve the status of free Black citizens in the United States.

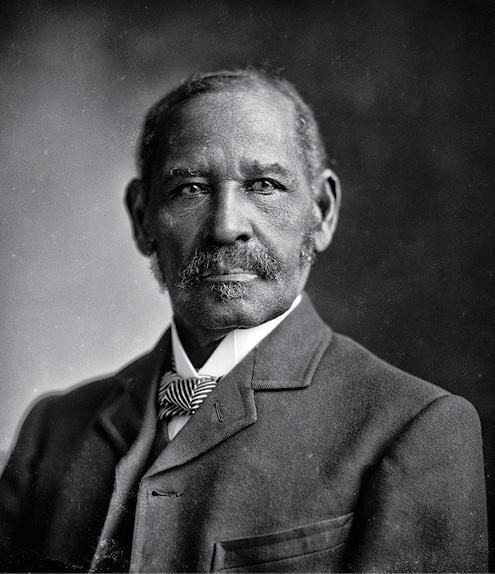

Mifflin Gibbs in particular had been an anti-slavery activist since his youth in Philadelphia, where he had been born in 1823. According to Goodspeed’s History of Pulaski County, his father had been a Methodist minister who died when Mifflin was eight years old. Raised by his mother, he worked as a stable boy until, at sixteen, he apprenticed to a Black carpenter who had bought his own freedom.

With little opportunity for formal education, young Gibbs read voraciously. He joined the Philomathean Society, a literary association, and he seems to have grown up in a culture of Bible study and political debate.

Gibbs had also been a member of the Anti-Slavery Society. He worked for the Philadelphia “station” of the Underground Railroad, helping escaped slaves travel north to freedom in Canada. At the age of twenty-two, he had been part of a delegation to petition the Pennsylvania state government for Black enfranchisement. He had spoken publicly at a rally held to honour Louis Kossuth, the Hungarian liberator—a rally to which Black people had not been invited.

In 1849 he attended the National Antislavery Convention, held in Philadelphia. A year later he had travelled through Ohio, Pennsylvania and New York state with Frederick Douglass himself, speaking against slavery to often-hostile audiences.

This was a remarkable period in American history, when free Black Americans were struggling to find a place for themselves and their enslaved brothers and sisters.

As Jacqueline L. Tobin and Hettie Jones show in their book From Midnight to Dawn, the Underground Railroad was just one aspect of a liberation movement that included propaganda, education and covert action. Educated Black activists met in yearly conventions that helped shape the politics of a country that rejected them—and a convention in San Francisco would shape the future of Canada. In that turbulent time, Frederick Douglass was arguing for some kind of integration with White America. His equally brilliant adversary, Dr. Martin Delany, advocated for a Black nationalism, whether in North America, Latin America or Africa. Some argued for new colonial ventures, like Sierra Leone and Liberia, where Black Americans might govern themselves and their African cousins. Others wanted to emigrate and integrate—whether in Canada or Latin America.

Mifflin Gibbs would have been in the centre of this debate. When travelling in Ohio, he may well have met Black students at Oberlin College, one of the first American schools to admit both Black and female students. Its students were to be the first educated Black elite, and some of them would play an important part in Canadian history as well.

Gibbs would also have met many of those White and free Black activists involved in covertly moving escapees from the South to “Upper Canada,” as Ontario was then known. He knew that Black conventions were discussing mass migration to Upper Canada, and it must have seemed an attractive idea. Thousands of escaped slaves had already settled there, and communities like Buxton were flourishing.

But at the end of the speaking tour, disheartened and with no real sense of opportunity in Philadelphia, Gibbs shared his feelings with Julia Griffiths, an English-born White abolitionist who was Douglass’s business manager. As Gibbs described in his autobiography, Shadow and Light, her answer changed his life: “I shall never forget the response; almost imperious in manner, you could already anticipate the magnitude of an idea that seemed to struggle for utterance. ‘What! Discouraged? Go do some great thing.’”

He did. On borrowed money, Gibbs travelled steerage class to San Francisco in 1850, where he arrived with sixty cents in his pocket. He worked at everything from carpentry to shining shoes. In 1852 he went into partnership with Peter Lester, and their business flourished.

Gibbs hadn’t left his political activism behind him in Philadelphia. In 1851 he was one of a group of Black activists who published a protest against their lack of the vote—a protest that startled many complacent Californians. In the mid-fifties, Gibbs took a major part in the Black conventions that met repeatedly to draft memorials to the state legislature in Sacramento, just as conventions back east had tried to influence state and federal governments. He was also one of the publishers of California’s first Black newspaper, The Mirror of the Times.

As if this were not dangerous enough, Gibbs may have also renewed his work with the Underground Railroad. According to Jerry Stanley’s book Hurry Freedom, Gibbs hid fugitive slaves in the basement of the boot shop until they could be smuggled onto ships bound for South America. This was both illegal and dangerous. Had he been caught, Gibbs could well have been sent to New Orleans and sold into slavery. But he himself never mentioned it in his memoirs, and no other source corroborates Stanley.

Gibbs clearly preferred to work within the system when he could—to win under White rules by patient agitation and economic success. At the end of his long career, he was to advise Black youth: “Labor to make yourself as indispensable as possible in all your relations with the dominant race, and color will cut less and less figure in your upward grade.”

Good advice, no doubt, but in the 1850s Gibbs witnessed a concerted effort to make Black Californians as dispensable as possible—to solve the “Negro question” by driving the Black population out of the state.

Anti-Black feeling had existed in California since the gold rush. Almost as soon as it came into existence, the state legislature, in its 1850 Civil Practice Act, had disqualified Black Californians from testifying against White people. When, in 1853, a memorial was presented to the legislature asking for repeal of that provision, one of the assemblymen suggested, amid much hilarity, that the request be thrown out the window. His motion was carried unanimously.

Such an attitude was predictable in a state with a sizable minority of White Southerners and with a government dominated by Democrats sympathetic to the South. In criticizing the law disqualifying Black people from testifying, a San Francisco newspaper editorialized in 1857: “It is maintained in force simply because a class of our people were brought up in states where negroes were not allowed to testify, not because they were negroes, but because they were slaves, and their vehement adherence to the prejudices of their birthplace has infected the popular mind.”

The state legislature did not stop with one law. A Fugitive Slave Act was passed in 1852; this permitted the arrest of any escaped slaves found in the state and their return to servitude, provided they were taken out of California. As if the Civil Practice Act were not enough, the 1852 law specified that “in no trial or hearing under this Act shall the testimony of such alleged fugitive be admitted in evidence.”

The Act had been used almost at once against three slaves owned by a Georgian named Perkins, who had had them arrested and transported back to the South. The slaves were unable to testify that Perkins had promised them their freedom when he had brought them into the state in 1849 and had allowed them to work for themselves to earn money to buy themselves out of slavery.

Black Californians whose freedom was unquestioned also faced legalized injustice. In San Francisco they owned five million dollars’ worth of property and were taxed accordingly, without having a say in the matter. They also paid a poll tax—in effect, a charge for being able to vote. But when they tried to vote, they were driven from the polls.

Mifflin Gibbs and Peter Lester protested this unfairness by refusing to pay the poll tax in 1857. Their goods were promptly seized and put up for auction to pay the tax. However, a sympathetic White Southerner persuaded the others at the auction to “give the goods a severe letting alone.” Since no one bid on them, the goods were returned. Thereafter, the poll tax was no longer enforced.

Peter Lester’s family also faced discrimination when the San Francisco public schools were segregated in January 1858. His daughter Sarah was expelled from the school she had been attending. A minority on the all-White school board argued that an exception should be made in her case, since she was no darker than her classmates.

The problem, as the Black Californians realized, was not really the Southerners in the state; it was the Northern White majority, who detested all Black people, free or slave. Their point of view was expressed in an 1857 newspaper editorial praising Oregon’s new constitution because it expressly forbade free Black people from entering the state: “It is much better to keep them away than to let them come, and deprive them of all civil rights and the power of defending themselves, as is done in this state.”

California’s doubtful status as a free state was further undermined when John B. Weller was inaugurated as governor in January 1858. In his first public statement, Weller straddled the fence on the national issue of slavery. California had chosen to forbid it, he observed, but to attack slavery elsewhere in the Union was unwise, since it amounted to meddling in other states’ internal affairs and would “weaken the ties of affection between the States.”

Such hypocrisy was typical of the attitudes that led within a few weeks to a crisis that nearly took California into the pro-slavery camp and that led directly to the Black migration to the Northwest.

The Case of Archy Lee

The issue was the fate of Archy Lee, a “fugitive slave” of nineteen who in January of 1858 was being held for deportation. His owner, a young Mississippian named Charles A. Stovall, claimed to be travelling for his health through the state, not residing there permanently. Lee, his slave for many years and valued at fifteen hundred dollars, had accompanied him on the western journey as Stovall’s manservant.

For a transient, Stovall had made himself very much at home in California. He had “traveled for his health” with a herd of cattle, which he placed on a ranch he had purchased in Nevada’s Carson Valley. He hired a schoolroom in Sacramento and advertised for pupils, and he put Lee out to work while collecting his wages.

The US commissioner who heard the case ruled that Lee was not a fugitive slave and therefore could not be deported, but the commissioner declined to decide what should be done with him. He turned the case over to the state court.

Abolitionists and supporters of slavery followed the case closely, and each side gave what help it could. The Black community of San Francisco raised money for Lee’s defence, while Stovall’s friends in the state legislature tried to strengthen the Southerner’s cause. On January 18, just a week after the case had become public knowledge, Assemblyman A.G. Stokes introduced a bill providing that when a slave “shall be brought or may have been heretofore brought” into California by an owner only travelling through—or briefly sojourning—the owner should have his property restored to him if the slave attempted escape.

This bill would not merely have given Stovall legal grounds for regaining possession of Archy Lee; it would have legalized slavery in California.

Stokes went on, a few weeks later, to frame another bill “to prohibit the immigration of free negroes and other obnoxious persons into this state and to protect and regulate the conduct of such persons now within the state.”

The political atmosphere surrounding the case grew still more acrid in February, when the state Supreme Court handed down its decision—a decision that at once took its place as one of the most astounding judicial farces in American history. Chief Justice Terry and Judge Burnett ruled that Stovall was not visiting or travelling in California, and was therefore a resident of a free state who was trying to uphold slavery in that state.

But since Stovall was ill, insolvent and young, and this was the first such case to arise in California, they continued: “We are not disposed to rigidly enforce the rule for the first time. But in reference to all future cases it is our purpose to enforce the rules strictly according to their true intent and spirit.”

A later Supreme Court judge, in commenting on this decision, observed that it “gave the law to the north and the [Black man] to the south.” He added that Terry and Burnett had in effect declared that the constitution did not apply to young men travelling for their health; it did not apply the first time; and Supreme Court decisions were not to be taken as precedents. Black Californians and abolitionists also met the court’s decision with an eruption of outrage.

Stovall, however, had Lee. Seeing that California was no longer a very good place for his health, he arranged to sail for Panama on the steamer Orizaba on March 4. Until then, he kept Lee secretly locked up in the San Joaquin county jail.

The Black community discovered Lee’s whereabouts and applied for a writ of habeas corpus to gain his release. Stovall evaded being served with this writ and hid Lee elsewhere. Undiscouraged, the community made plans for a dramatic last-minute rescue.

The Orizaba left San Francisco as scheduled on March 4, but Stovall and Lee were not on board. As the steamer approached the Golden Gate, however, a small boat carrying the two men put out from shore and came alongside. Thinking he had outwitted his enemies, Stovall was chagrined to find policemen on board with a warrant for his arrest on a charge of kidnapping.

Furious, he drew a pistol, but the police quickly disarmed him after a scuffle. “The Supreme Court gave me this boy,” he shouted, “and I’ll be damned if any other court in this state will take him away.”

The police took Stovall and Lee off the steamer and rowed back to a city shivering with tension. A large crowd of Black onlookers had gathered on the docks to welcome Lee back, but they were far from overjoyed: news had just reached them that the state senate judicial committee in Sacramento had recommended continuance of the prohibition against Black testimony. Lee’s oppressor might well escape punishment thanks to that law.

On Friday, March 5, a mass meeting was held in the Zion Methodist Episcopal Church at Pacific and Stockton to support Archy Lee’s cause. A large, mostly Black crowd contributed $150 to his legal costs and set up a committee to raise more. This was to be the first in a series of meetings; their purpose would evolve from saving one person to saving the whole community.

The following Monday, in a packed courtroom, Judge Freelon turned down Stovall’s application to dismiss the writ of habeas corpus. Stovall’s lawyer, seeing nothing to do, consented to Lee’s being given his freedom. The crowd was then astounded to see him arrested as a fugitive slave and ordered back to jail.

A near-riot broke out. The US Marshal charged with escorting Lee to jail had to call for reinforcements before he could get the young man out of the courtroom. Lee was dragged through the streets at the head of an angry procession of Black and sympathetic White protestors; several Black men were arrested for assault and battery before Lee was behind bars again.

To the Black community of San Francisco, this stunning development must have seemed like proof that the law was a grotesquely flexible set of rules designed to keep them in bondage. But they stubbornly fought on in the courts.

Their trust in the law must have been further shaken on March 19, when Bill 339 was introduced in the legislature by J.S. Warfield: “An Act to restrict and prevent the immigration to and residence in the State of negroes and mulattoes.”

Obviously intended as an improvement on Stokes’s earlier efforts, Bill 339 was grossly racist. Under its provisions, no Black person would henceforth be allowed to immigrate to California. Those who did would be deported at their own expense, for the state would be empowered to hire them out, as slaves often were, to anyone “for such reasonable time as shall be necessary to pay the costs of the conviction and transportation from this state before sending such negro or mulatto therefrom.”

Black people already residing in the state would have to register; failure to do so would be a misdemeanour. Every registered Black resident would have to be licensed to work, and anyone employing an unlicensed Black resident would be heavily fined. Probably the cruellest provision of the bill would have made it a misdemeanour to bring slaves into California with the intent of freeing them. This provision was aimed at Black residents who, having bought their own freedom and earned enough money, wished to buy the freedom of their own families still in the slave states.

The effect of Bill 339 would have been to legalize slavery in California as long as the government itself was the slaveholder. The bill enjoyed considerable support—we are all socialists when the government does what we want it to—but also suffered some sharp criticism. One of the best rebukes to Warfield came from Mifflin Gibbs in a letter to the San Francisco Daily Evening Bulletin:

"I appeal with pride to the history of the free colored people for the last twenty years in every free state in the Union . . . During all that time, notwithstanding they have been subjected to the most unjust enactments and coerced by rigorous laws, pursued by a prejudice as unrelenting as inhuman, disregarded by the Church, and persecuted by the State—they have made steady progress, upward and onward, in oral and intellectual attainments.

I admit the right of a family or a nation to say who, from without, shall be a component part of its household or community; but the application of this principle should work no hardship to a colored man, for he was born in the great American family, and is your Black brother—ugly though he may be—and is interested in its weal or woe, is taxed to support it, and having made up his mind to stay with the family, his right to the benefit of just government is as good as that of his pale face brother who clamors for his expatriation. . . .

Let the bill now before the Legislature take what turn it may, the colored people of this state have no regrets to offer for their deportment. Their course has been manly, industrious, law-abiding. To this Legislature and the press that sustains them be all the honor, glory, and consequences of prosecuting an industrious, unoffending, and defenceless people.

"

(Surprisingly, Gibbs does not mention Bill 339, or his battle against it, in his autobiography.)

The case of Archy Lee now took another bizarre turn. Stovall made a new affidavit in an attempt to make Lee seem to be a fugitive slave. Stovall claimed that Lee had assaulted someone in Mississippi in January 1857 and had then fled west. Stovall, traveling west a little later, had encountered Lee by chance on the North Platte River and travelled on to Sacramento with him.

Obviously Stovall was relying on the Civil Practice Act to keep Lee from disproving this new story. He was also relying on either stupidity or blind partisanship in the US commissioner who heard the case, George Pen Johnston, a Democrat. Johnston, politically sympathetic but no fool, ruled that Lee was not a fugitive slave and granted him his freedom on April 14.

Though delighted with the decision, the Black residents of San Francisco did not deceive themselves that a new era of racial justice was at hand. Bill 339 was still moving through the legislature to what seemed inevitable enactment. (It did not, in fact, become law, but only because last-minute amendments prevented its coming to a vote before the legislature adjourned. According to California historian Rudolph M. Lapp, the bill failed because the legislature was “very impatient and partially drunk.”)

All the other repressive laws were still on the books, and California was still a violent state where many disputes were settled with a gun. In fact, Commissioner Johnston himself was to kill a man in a duel before the end of summer, and Gibbs in his autobiography would later recall the vigilance committees, stuffed ballot boxes and assassinations that dominated San Francisco’s politics in the 1850s.

In the spring of 1858, therefore, the city’s Black residents had poor prospects. Those who had sweated to earn money or property saw little chance of holding what they had gained. Those who had yet to succeed saw little chance of doing so. They were a tiny minority, an estimated four thousand out of the state’s half-million. California was an El Dorado for White men only.

On the night of Archy Lee’s liberation, a mass meeting was held again at Zion Church, partly to raise an additional four hundred dollars for Lee’s legal costs but chiefly to discuss possible destinations for a mass emigration of the Black community.

The meeting opened with a hymn entitled “The Year of Archy Lee,” composed for the occasion:

"Blow ye the trumpet! Blow!

The gladly solemn sound,

Let all the nations know

To earth’s remotest bound

The year of Archy Lee is come,

Return, ye ransomed Stovall, home.Exalt the Lamb of God!

The sin-atoning Lamb;

Redemption for His blood

Through all the land proclaim.

The year of Archy Lee is come,

Return, ye ransomed Stovall, home.Ye slaves of sin and hell,

Your liberty receive;

And safe in Jesus dwell,

And blest in Jesus live.

The year of Archy Lee is come,

Return, ye ransomed Stovall, home.The gospel trumpet hear

"

The news of pardoning grace;

Ye happy should draw near

Behold your Saviour’s face.

The year of Archy Lee is come,

Return, ye ransomed Stovall, home.

Another song celebrated the liberation of Archy Lee. It was “A Song of Praise,” subtitled “For the Benefit of Those Named Therein.”

"Sound the glad tidings o’er land and o’er sea—

"

Our people have triumphed and Archy is free!

Sing, for the pride of the tyrant is broken,

The decision of Burnett and Terry reversed.

How vain was their boasting! Their plans so soon broken;

Archy’s free and Stovall is brought to the dust.

Praise to the Judges and praise to the lawyers!

Freedom was their object and that they obtained.

Stovall was shown it was time to be moving;

He left on the steamer to lay deeper plans.

But there was a Baker, a Crosby, and Tompkins

Before Pen Johnston and did plead for the man.

After Lee himself was presented to the cheering crowd of five hundred, the meeting turned to discussion of emigration. Most of the participants must have grown up in the eastern US and would have been very familiar with the idea after the years of debate within the Black American community.

Three possibilities presented themselves: Panama, the Mexican state of Sonora and the British colony of Vancouver Island. Since most of the participants had seen enough of Panama en route to California, they expressed little interest in this choice. However, an inquiry was sent to General Bosques, president of the Panamanian Senate. (His very favourable reply arrived in July, when the emigrants were committed to Vancouver Island.) One man argued strongly for Sonora as a better site for a farming settlement, but he aroused little interest. Sonora, just south of the Arizona Territory, had already suffered several “filibusters”—raids by Americans seeking to annex it to the US—and it seemed certain to become American territory before long.

Interest in Vancouver Island was heightened by the appearance at the meeting of Jeremiah Nagle, a fifty-six-year-old sailor and landowner in the colony. He was also the captain of the steamer Commodore, which was making regular voyages between San Francisco and Victoria, the chief settlement on Vancouver Island.

Standing by the pulpit with maps of Vancouver Island, Nagle answered a rapid stream of questions about the colony. He also had with him a letter from “a gentleman in the service of the Hudson’s Bay Company of undoubted veracity,” giving details about the colony and welcoming the Black Californians. This gentleman must have been the governor himself, James Douglas, but his letter does not appear to have survived.

In reporting on the meeting, the Daily Evening Bulletin predicted that the emigration would come to nothing, but on April 19 another meeting was held to form a Pioneer Committee of sixty-five Black emigrants who were to embark next day on the Commodore for Victoria. In the event, only thirty-five were able to clear up their affairs in time, but the next day they were seen off by almost the entire Black community at the wharves.

It was a noisy, confused afternoon. In addition to the Commodore, two other vessels—the Golden Age and the Columbia—were also leaving for the north; each had a “barker” extolling the advantages of his own ship. Fruit vendors and newsboys wandered through the crowds. Mifflin Gibbs gave a farewell address to the Pioneer Committee, but no one paid much attention.

The reason for the uproar was simple enough. Nagle had also brought confirmation of the rumours that had been filtering down from the Northwest: gold had been found on the Fraser and Thompson rivers, in what was then called New Caledonia. And Victoria was the gateway to the goldfields.

As the Commodore steamed out of San Francisco on that spring afternoon, the members of the Pioneer Committee must have felt mixed emotions. Ahead was a land that seemed to promise equality, opportunity and perhaps even great wealth. But the four hundred White men who were their fellow passengers must have looked grimly familiar.