Hook, Line and Sinker

Of all fishing gear, the most familiar is the fish hook. Over thousands of years the Indian peoples of the Northwest Coast designed and perfected hooks and their accessories—baits, lures, sinkers, floats, and lines—for fish of various sizes, habitats, characteristics, and behaviour. Their fishing gear was so well suited to the environment, and their skill so practised, that they saw no need to change when white men sailed into their waters and introduced other kinds of hooks. The bone barb was eventually replaced with one of iron; linen thread or hemp string took over from spruce root, and rope replaced the kelp line, but the hook remained essentially the same.

In 1885 Albert Niblack, on a survey of northern British Columbia and Alaska, wrote in his report published by the U.S. National Museum: “The apparently clumsy hooks of this region have been found to possess so many advantages over the type used by Europeans that they are retained to this day.” He wistfully adds, “There is little in the art of fishing we can teach these Indians.”

In truth, there is much in the art of fishing that the natives could have taught the newcomers, particularly in the early years. Captain Dixon and his crew, for example, anchored their square-rigged ship in a sheltered bay in 1787 and lowered a boat so that the crew, hungry for fresh food, could catch fish. The results of using European fishing gear and fishing methods on this coast must have been less than encouraging, judging from an entry in Dixon’s journal. He describes the Indians’ successful method of catching halibut with their baited hooks, lines, and floats, then remarks:

“Thus we were fairly beat at our own weapons, and the natives constantly bringing us plenty of fish, our boat was never sent on this business afterwards.”

In Captain Vancouver’s journal is another instance of Indians’ supplying fish to white men whose fishing attempts have failed. Of the canoemen who followed him up what is now Burrard Inlet, he reports:

“Our Indian visitors remained with us until, by signs, we gave them to understand we were going to rest, and, after receiving some acceptable articles, they retired, and, by means of the same language, promised an abundant supply of fish the next day, our seine having been tried in their presence with very little success.”

A great many journals and diaries recounting the early days of the white man’s visits tell of quantities of fish being brought to the ships, either as gifts or for trade. Many a ship’s crew was indebted to the skill of native fishermen. And to the native’s fish hook.

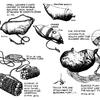

The size, shape, material, and manufacture of hooks show a wide range of ideas and techniques. Baited hooks were used in trolling for salmon and for catching cod, dogfish, kelpfish, and other species. Undoubtedly some worked better than others and some lasted longer.

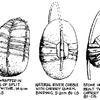

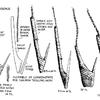

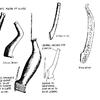

Tiny fish hooks of wood tipped with slender bone barbs have been unearthed in archaeological excavations, while many museums house large, elaborately carved wooden halibut hooks complete with line and float. Also found archaeologically are fish hook shanks of stone and bone. These shanks are not frequently found, yet interestingly the bone ones excavated in the Queen Charlotte Islands (Haida) are similar to those of slate from Yuquot (Nootka) and from Sooke (Coast Salish), both on Vancouver Island. Neatly carved and shaped to receive the barb at the correct angle, often with a heel to prevent the barb lashing from slipping, they are also grooved to secure the leader. As well as being durable, such hooks also acted as their own sinker.

Fishing Lines

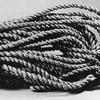

Excellent lines for the fisherman came from many materials. Perhaps the most ideally suited was the bull kelp (Nereocystis luetkeana), a seaweed found in rocky areas along the whole coast in the upper subtidal zone and to a depth of several fathoms. From its holdfast, a rootlike structure tenaciously clinging to the rock, the seaweed sends out a long stipe, like a stem, for up to 25 metres (about 81 feet). The stipe, about one centimetre (3⁄8 inch) in diameter at the base, is cylindrical and solid, gradually increasing in thickness to become a hollow tube terminating in a bulb which serves as a float to hold the seaweed up. The solid part of the stem was used for fish lines after being soaked in fresh water, stretched, and twisted for extra strength. Lengths of these were joined together with a special knot to give the fisherman a long line of great strength.

I handled one of these coiled-up lengths of kelp line in the American Museum of Natural History, in New York, and became interested in the type of knot used in joining the many lengths of kelp. Using my shoe laces I studiously followed the intricacies of the tied kelp ends and finally succeeded in learning to make the knot. Back on the west coast of Vancouver Island that summer and involved in a survival course, I showed my achievement to a knot-tying friend instructing in outdoor education and mountain climbing. “That,” he observed, “is called a fisherman’s knot!”

The following year I found some medium length kelp stipes freshly washed up on the beach after a wild wind and rain storm that had howled down the coast all day, making August seem like December. Sheltered by a stand of spruce our camp had withstood a taste of the unleashed temper of the outer coast, though my sleeping bag took a soaking, and I thought again of the big planked houses of the early Indian people. How comforting it must have been when the wind blew to have a fire burning, food in the cooking box, and dozens of people adding to the warmth.

From the kelp stipes I made, by soaking, stretching, twisting and knotting together, a 14-metre length of fish line. The 0.7-centimetre (¼-inch) thick kelp stipe blackened and shrank to a thin line. Tough and wire-like, it was unrecognizable as kelp, but when immersed in water again it reverted to its original thickness within the hour, maintaining the twist.

Whale sinew was utilized for lines, as was nettle fibre. Fishing lines of inner cedar bark were common along the entire Northwest Coast, and were used particularly where a heavy line was needed. In Old Masset, also called Haida, in the Queen Charlotte Islands, I watched the gnarled but deft hands of 74-year-old Hanna Parnell twisting lengths of split inner cedar bark into a three-strand rope, “for halibut line” she said in her native tongue. Hanna had already completed about 18 metres (60 feet) of the strong pliable rope, and I felt a deep admiration and respect for a woman who still maintained the knowledge and skill, and indeed the enjoyment, of making a useful item from the materials of her environment. Her grandchildren, accustomed to diesel-powered, electronically equipped fishing vessels with sonar depth sounders, were more familiar with nylon lines and steel hooks mechanically winched in over the side of the boat to bring in halibut for the fish packing plants.

Hanna Parnell knew that her cedar bark line would never feel the pull of Great-One-Coming Up-Against-the-Current, but her experienced hands prepared the cedar bark and made the rope anyway, and it seemed to me that it was serving another purpose, in another era, with just as much meaning.

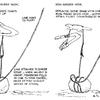

Sinkers

Sinkers varied in size from a small pebble to a hefty rock either grooved or perforated for attaching to a rope. The larger sinkers functioned as anchors to maintain the position of an item of fishing gear underwater; a cluster of these stones provided anchorage for a dugout and its crew. Small and medium-sized sinkers were used with a hook and line.

Similar stones weighted the bottom edge of a net to hold it taut. Many of these weights were smooth, unmodified river cobbles secured to the net in various ways with pliable twigs and lashings. Now that techniques exist for preserving materials from archaeological “wet sites” (water-saturated digs), excavation is going ahead in sites where these net weights, complete with lashings, are being found in a good state of preservation as a result of their waterlogging.

When a large sturgeon tried to escape the hook by heading out to sea, pulling the canoe after it, a kind of sea anchor was used. A heavy stone on a length of rope was tossed over the side to slow down the progress of the fish.

Steam-Bent Hooks

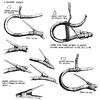

The U-shaped, steam-bent hook was the characteristic halibut hook of the southern and central peoples, although this type of hook would also catch cod and dogfish and its smallest version took kelpfish.

The Makah, great halibut fishermen, frequently made their hooks out of yew wood; others used fir, balsam, spruce or hemlock knotwood. The flaring, curved back tip of the hook ensured that the fish only took the baited part carrying the barb, since it could not open its mouth wide enough to include the curved tip.

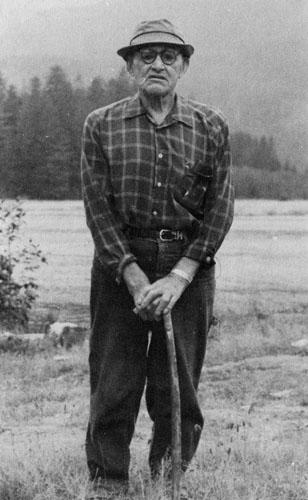

During my research on fishing gear, I heard about a very old Indian man living in Port Renfrew, on the west coast of Vancouver Island, who used to make and use steam-bent hooks. The better part of a day’s journey, by ferry and a winding, rocky, washboard road that clung high up the mountain side as it followed the coast, eventually brought me to the village, the reservation, and Chief Charles Jones of the Pachenaht Band.

Although Chief Charles was busy in his workshop, a small tidy shed by the river’s edge, he bade me enter and pulled up a stool for me. He had used the U-shaped hooks for fishing up until 1950 or so; he said he still made them for sale to anyone who cared to buy them. He spoke of going into the forest to find the right wood, and shaping it. As he described the steam-bending process, his powerful, gnarled hands mimed the careful bending of the wood to the U-shape. I felt the sensitivity of fingers that told him when the wood had steamed long enough to begin the bending. “Gotta be just limber,” he said, “when it’s just limber then it bends right.”

I asked the chief a lot of questions about the old ways of fishing, and showed him photos I had taken of different hooks from various museums. With each photo he either nodded, as if in recognition of an old friend, and described how the hook was used, or denied it for his area, Southern Nootka. “That’s a Haida hook, we never used that… Kwagiutl, they made that kind of hook…”

Of the curved back arm of the steam-bent hook, he told me that this prevented the fish from fighting. If the arm were straight, it would cause more discomfort by lying on the cheek of the fish, and “he’ll fight all the way up to the top.” He also said the curve prevented the hook from being swallowed by too small a fish; it could only be snagged by the lip, from which the hook could be removed and the fish returned to the water unharmed.

I felt privileged to share a small part of the great storehouse of Chief Charles’s knowledge, but also I felt somewhat inadequate in the shadow of his experience and wisdom. Eventually we parted. I thanked the Chief and offered him a lift back to his house, but no, he preferred to walk. With upright back and cane in hand he went off down the road and I went to my car.

As I caught up with him I felt a compulsion to satisfy my curiosity about his age, and pulled up beside him. “Chief Charles, may I ask you one more question?”

“Sure!” he nodded, his voice booming.

“How old are you?”

“I’ll be a hundred years old in July!” he said,2 and his eyes sparked with the joy of that thought. And I shared his joy.

For a considerable time there had been some dispute concerning the behaviour of the bentwood hook underwater. Did it float up from the point of attachment, or did it hang down? To try to find out, I made a halibut hook by steam-bending a quarter section of wood cut from a yew branch. I lashed on a bone barb with split cedar root, baited it with octopus and lowered the hook, with its stone sinker, into a tub of water. The hook floated up from the sinker.

I should have been satisfied, but there were still some doubts. I raised the question with Donald Abbott, Curator of Archaeology at the B.C. Provincial Museum in Victoria. He admitted that the answer had never been settled to everyone’s satisfaction, although he had heard of an old timer who had lost several hooks overboard that sank. I felt that these might have been the more recent iron-barbed hooks, not the earlier bone-barbed hooks such as the one I had made.

To settle the matter once and for all, Abbott obtained permission to take a classic bentwood bone-pointed halibut hook out of the museum’s ethnology collection for testing. That particular hook, from Barkley Sound, had been checked by Jan Freidman, an expert in wood identification known for her work at the famous Ozette archaeological site at Cape Alava, Washington. She had said that it was made from fir.

Abbott secured octopus bait to the hook, donned his diving gear, and in the chilly ocean waters of a January day went down to a depth of 40 feet, taking the hook with him. The result was that the hook sank.

I was convinced of the hook’s behaviour but had to discover why fir wood should sink when yew, a more dense wood, floated. The answer lay in which part of the wood was used for making the hook. The wood from a knot, where the branch grows through the trunk, is extremely hard and dense. Even when a fallen tree has rotted, the spike of the knot is still sound, and it was this wood, from fir and other trees, which was used to make the tough bentwood halibut hooks.

Salmon Trolling

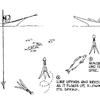

Salmon could be caught in great numbers in traps and dams once they began their migration up river, but they were also successfully caught by trolling with hook and line in the bays and inlets, especially when they congregated prior to the run.

John R. Jewitt, a ship’s armourer held captive by the famed Nootka Chief Maquinna for two years (1803–1805), describes the method of trolling in the narrative written from the diary he kept.

“One person seats himself in a small canoe, and, baiting his hook with a sprat, which they are always careful to procure as fresh as possible, fastens his line to the handle of the paddle; this, as he plies it in the water, keeps the fish in constant motion, so as to give it the appearance of life, which the salmon seeing, leaps at it and is instantly hooked, and by a sudden and dextrous motion of the paddle, drawn on board. I have known some of the natives take no less than eight or ten salmon of a morning, in this manner, and have seen from twenty to thirty canoes at a time in Friendly Cove thus employed.”

The “sprat” referred to was most likely a shiner, which the Nootka caught for bait in small stone dams.

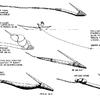

The Northern Halibut Hook

One of the largest fish to be caught along the coast, the halibut was particularly important to the people of the north coast, where the salmon was not caught in the quantities available to the more southern people.

Hatched in deep water, developing halibut float freely for the first six months of life. As they rise to the surface, these flat fish are carried by wind-driven currents onto the shallower section of the continental shelf. Here the fish rotates so that its broad surface is parallel to the sea bed.

Now it is a bottom feeder, and to adapt to this change the fish’s left eye migrates over the snout so that both eyes are on the upper surface. The mouth is then to one side, giving the head a strange, twisted look. The average weight of a halibut is between 30 and 36 pounds, but fish up to 200 pounds used to be taken by hook and line.

Although all coast tribes caught halibut, the Makah on the Olympic Peninsula in Washington and the Haida and Tlingit in the north were the most extensive harvesters of this fish, some venturing great distances to reach major halibut banks.

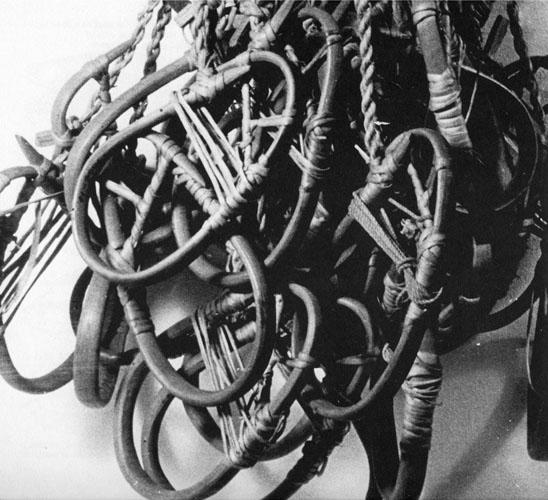

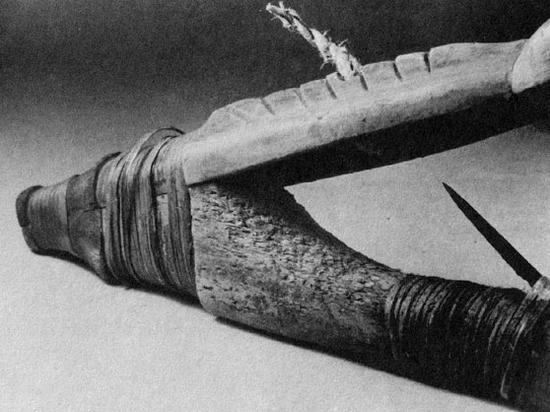

One of the most interesting and beautiful of all fish hooks is that used by the northerners for catching this great fish. This is the “clumsy hook” referred to by Niblack: two sections lashed together in a V shape. One arm of this “V” was often carved with a significant design. Since a halibut fisherman required a spirit helper, or power, to be successful in catching this very large and powerful fish, it seems likely that the designs had a significance relating to power. Two common figures were that of the octopus, or devil fish—a common bait for this hook—and that of a woman. “Old Woman” was one of the many names used for the halibut; songs and legends were the sources for many others, including:

- Scenting Woman

- Wrinkled-in-the-Mouth

- Born-To-Be-Giver-of-the-House

- Flabby-Skin-in-the-Mouth

- Squint-Eye

- Old-Coming-Across-Going-Around-Island

- Never-Appearing-Going-Around-the-Island

- Big-One-Who-Comes-Taking-Pebbles-into-the-Mouth

- Rising-Steeply

- Great-One-Coming-Up-Against-the-Current

The undecorated arm of the V hook had a barb lashed to it, and it was this barb, impaled in the mouth of the fish, that held it firmly. Some of the barbed arms of hooks found in museums are rough and shredded from the frantic biting of the captive halibut; sometimes fish must have remained on the hook for some time before the fisherman returned to haul in the line. Since many of these hooks are comprised of two different woods which appear to be of different age, it seems very possible that a chewed-up section, when too badly damaged, would be discarded and a new piece fitted to the carved arm.

With the increasing introduction of metal to the coast cultures, iron replaced bone for the barbs of many fish hooks as they were made or repaired. Iron was a stronger ally against a large, fighting fish, but I believe that it also created a new problem. When baited with devil fish, which floats, the wooden hook maintained its correct position under the water, but when an iron barb was used, the equilibrium was destroyed and the hook sank. It became necessary to add a small float near the hook to counteract this effect. Among the many hooks I examined in the course of research for this book, these small floats were attached only to hooks having iron barbs. In one instance where the complete hook, not just the barb, was of iron, the float was correspondingly larger.

Sailing in the territorial waters of the northern Tlingit in 1787, Captain Dixon described the halibut fishing of the Indian people in his journal:

“They bait their hooks with a kind of fish… or squid… and having sunk it to the bottom they fix a bladder to the end of the line as a buoy… One man is sufficient to look after five or six of these buoys; when he perceives a fish bite he is in no great hurry to haul up his line, but gives him time to be well hooked, and when he has hauled the fish up to the surface of the water he knocks him on the head with a short club. This is done to prevent the halibut (which sometimes are very large) from damaging or perhaps upsetting his canoe in their dying struggles.”

To find out exactly how the halibut took its hook, I visited the Pacific Environment Institute in West Vancouver, where fish are kept outdoors in large round tanks for a variety of studies, including the effects of pollution.

In a tank housing half a dozen halibut, the water level was lowered to a few inches so that I could see the fish better and take photographs. Pieces of codfish were tossed into the tank and I saw that the halibut did not bite at the food the way a salmon or trout does, but drew it in with a strong sucking action, much like that of a vacuum cleaner. If the food taken in was acceptable, it was retained; otherwise it was expelled with equal force. The native V-shaped hook owes its success to a design that accommodates the flat shape of the fish and responds to the fish’s method of eating. The bait, wrapped around the barb, was taken into the mouth, but because it could not be swallowed it was rejected. The forceful exit of the angled barb caused it to penetrate the cheek on the underside, and the fish was hooked. It could not go forward to release itself because of the V shape, and its attempts to withdraw only secured the barb more firmly.

I was curious to see this hook in action. Not having the nerve to ask a museum to lend me a halibut hook to go fishing, I made one, complete with deer bone barb, spruce root lashing, inner cedar bark leader and line, and a perforated stone sinker. For luck I carved a river otter on one arm of the hook, a creature well experienced in the art of fishing. With a “gone fishing” sign on my door I returned to the Pacific Environment Institute and their tank of halibut. Before tying on the bait with a string of cedar bark I rubbed my hands with seaweed and held them in the salt water, as was customary, to remove the human scent. Ever co-operative, the fisheries biologist Don McQuarry stood by with a small tank of sea water containing anesthetic so that the fish could be subdued and the hook removed.

Down went the stone sinker; up floated the baited hook attached to the sinker. I held onto the cedar bark line and watched, saying the Kwagiutl prayer to Scenting Woman to take the “sweet tasting food” and “not to keep me waiting long on the water.” Twice a fish sucked at the barbed end of the hook only to reject it. A third attempt; the same. I then realized that the fish in the tank were too small to take the angled barb fully into their mouths, and I saw how the size of the halibut to be caught could be controlled by the size and angle of the barb, and the size of the hook.

I made another, smaller hook. This time I carved Raven flying with the sun in his beak, copied after the beautiful halibut hook in the Portland Art Museum that is one of my favorites. Then it was back to the Pacific Environment Institute. On went the bait and down went the sinker once more. From the bottom, Scenting Woman looked up and saw Raven taking the sun to the sky to bring daylight to all the world. The Old Woman smelled the squid wrapped on the hook, heard the words beseeching her to take the “sweet food,” and obeyed. There was a violent thrashing as the hooked fish fought for its life. I saw the hook embedded in its mouth and hurriedly hauled in the cedar bark line. But as she reached the surface the old Squint-Eye gave a mighty jerk, the leader broke, and she was free. Perhaps I should have been “in no great hurry to haul in the line.” It might have been that I lacked a spirit helper—the power considered so necessary for halibut fishing. In any event, I understood the urgency of the fisherman’s prayer to the hook, which he termed Younger Brother, when, hauling up the fish from a considerable depth, he said:

"“Now hold this, my younger brother,

Don’t let go this, my Younger Brother.”

"

When the hook was eventually retrieved I found pitted scuff marks on the wood where the halibut had tried biting off the end of the hook. The fish was only a small one, but its strength and spirit left me with a finer respect for fishermen who made their tackle and took their dugout canoes out to the halibut banks to entice Scenting Woman to the bait—men who spent long cold hours on the water to ensure that their families had food for the winter.

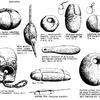

Lures

The Indians of the Northwest Coast used lures in ways that reflected close observation and intimate knowledge of marine life.

A sliver of willow—a white wood—carved in a fish shape with a slight curve gave a realistic imitation of a swimming fish as it was towed through the water. Uncarved pieces of willow in long strings trailing into the mouth of a net attracted the salmon by glimmering in the water. A piece of abalone glittering in the sunlight had the same effect as the polished metal flasher used by today’s angler; it caught the attention of the fish.

Perhaps the most cleverly devised was the codfish lure. Pushed down into deep water on a long pole, it was designed to rise slowly and enticingly to the surface, where the fish that followed it up—with predictable cod-like curiosity—met the fisherman waiting with a spear or dip net in his hand.

Floats

With characteristic aptitude for making a simple utilitarian object an item of beauty, the Indian fisherman frequently carved his wooden floats to represent a variety of creatures. Symbolism may have been part of the reason and perhaps it clarified ownership of the fishing gear, but the pleasure of seeing the gracefully carved sea bird, whale or swan riding the waves seems reason enough.

One of the most charming of these must surely have been the sea otter floating on its back, paws across its chest in the typical attitude of this animal.

Such floats mainly served to hold up and mark a halibut line, as did inflated seal skins or bladder floats. The small carved floats having a perforation from end to end were underwater floats used to maintain the correct position of some of the V-shaped hooks of the north.

Simpler, undecorated floats of wood supported the upper edge of fish nets; small ones along the length of the net, large ones at the ends.

Clubs

Part of a fisherman’s gear that he carried in the canoe, or used at the fish weir or trap, was the heavy wooden club for quickly killing the fish. These ranged from simple, bulbous-ended truncheons to highly decorated and even three-dimensionally carved works of art. Elaborate shaping and carving would not have been easy in the hardwood that was necessary for the making of these clubs.

In their book Indian Art of the Northwest Coast, William Reid and Bill Holm discuss the fine qualities of a large, slender and beautifully made club with superb carving. Artists and carvers both, they feel that the care expressed in the design and craftsmanship of the club might well have showed respect for the creature whose death it would bring about through its brutal but necessary use.

Compared with the Tlingit and Haida clubs, those of the south tended to be less elaborate and without decoration, but almost all were well carved and finished.

__________

2. July 1976.