Chapter 4 - The First, First Lady

Over 175 years ago, just beyond the palisades of the fur trading outpost Fort St. James, established by Simon Fraser in 1806, the courage of a shy young woman who kept a cool head during a terrifying crisis was to change the course of history. Situated on the southeast end of Stuart Lake, about 950 kilometres by road north of Vancouver, this small community of 2,046 people is an important Carrier First Nations settlement. But Fort St. James also ranks as the second-oldest continuously inhabited European settlement in the province. For nearly 40 years before Victoria was founded far to the south, Fort St. James would serve as the capital of New Caledonia, the British colony that comprised much of the Interior. Indeed, the British Columbia we know today might not have come to pass without the intervention of that young woman.

Amelia was the daughter of William Connolly, the Hudson’s Bay Company’s chief factor at Fort St. James, and Miyo Nipiy, a Cree woman. In 1828 she married a junior fur trader serving at the fort named James Douglas. Douglas had destiny printed in his soul. He would later found Fort Victoria, help blunt the American expansionism that would wrest much of the Oregon Territory from the Crown, secure British interests on the Pacific Slope, manage the turbulent gold rush of 1858, sign treaties with First Nations in a far-sighted policy later abandoned by greedy politicians, serve as midwife for the union of New Caledonia with Vancouver Island and end his career as the governor who presided over the birth of responsible, democratic government. But in 1828, Douglas was merely a brash and ambitious young clerk whose intelligence and skill had already come to the attention of his superiors but whose worth had yet to be proven.

The story of James and Amelia Douglas points to a fascinating moment that winked into existence about 200 years ago on the west side of the Rocky Mountains and then flickered out in the ruins of a human catastrophe of epic proportions. For a moment, it seemed that the collision of European and aboriginal cultures was about to bring forth something entirely new. A common language was being born—Chinook, the language of commerce forged from French and Mowachaht, Spanish and Halkomelem, English and Tsimshian, Hawaiian and Haida—and a generation like Amelia’s was emerging from marriages between First Nations and fur traders.

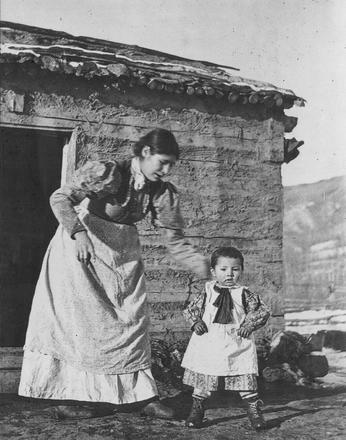

Life was hard on the fur frontier. Providing and preserving food for the long, bitter winters and manufacturing clothing for the harsh climate often dominated family life and much of this responsibility fell to the women. Childbirth and child-rearing often took place in isolation and under primitive conditions of sanitation and hygiene. Faced with long absences by their menfolk on trading missions and voyages of exploration, fur traders’ wives had to be tough, resilient and resourceful in an often hostile environment.

Aboriginal women who had been born into just such conditions understood the complexities of local politics. They had extended kinship groups upon which they could call for help in emergencies and they brought invaluable skills to marriage with a European man, many of which were marriages of convenience. For European men in the fur trade, the frontier was devoid of opportunities for a domestic life unless they turned to aboriginal women. Single men lived in military-style barracks, their Spartan lives punctuated by periods of excessive drinking and dangerous voyages. A number of these marriages were essentially political. In a landscape where the dominant society was aboriginal, powerful chiefs and astute fur traders sought in an age-old fashion to cement alliances, formalize access and expand trading relationships through marriage. As a result, much of BC’s non-Native and Native populations share common ancestries to an extent that many have either forgotten or prefer to repress.

For example, after British trader Robert Hunt’s European wife died around 1850, he promptly married Ansnaq or Mary Ebbetts, granddaughter of Shakes, a chief who monopolized fur trade routes to the Interior on the Stikine River. Mary’s mother, Chief of All Women, had been married to Abbitts, a Tlingit chief who controlled territory at the mouth of the Nass River. These women were typical in that they brought to their marriages the political weight of their rank and the prestige of family ties in a society that was deeply stratified with respect to class. Among Mary Ebbetts’s possessions when she married, for example, was a Haida slave. It has been pointed out by historians that many European traders set aside their “country wives” once they were no longer useful in economic or political terms and then travelled east to formally marry European women. William Connolly, Amelia’s father, was one who did.

Adele Perry, who delves into this complex social history in a brilliant piece of scholarship entitled On the Edge of Empire: Gender, Race and the Making of British Columbia, 1849–1871, provides evidence that attitudes toward First Nations, and particularly aboriginal women, became an expression of racist prejudice largely following the influx of British and American settlers. The Americans brought the prejudices of their Indian wars and many of the British newcomers aspired to status denied them at home and seized the opportunity to bestow rank upon themselves. Stereotypes were born when they encountered the ruins of once rich and powerful societies demoralized by successive epidemics that had depopulated the landscape, shredded cultural legacies and shattered their economic underpinnings.

Yet many of these personal relationships were also based in genuine love and proved remarkably resilient and durable, as did the affectionate marriages of James and Amelia Douglas and Robert and Mary Ebbetts Hunt. Mary and Robert had 11 children. One daughter, Sarah Hunt, married Alexander Lyon and helped him found the city of Port Hardy on Vancouver Island in 1904. Another daughter, Annie Hunt, married Stephen Spencer, an American cannery operator at Alert Bay. They had seven children and moved to Victoria in 1900, becoming part of the social establishment. And a brother, George Hunt, became the chief assistant of famed anthropologist Franz Boas.

|

The first citizen of Port Hardy If rugged self-reliance was the watchword for frontier marriages, there are few better examples than that of Alexander Lyon and Sarah Hunt. They left the Hudson’s Bay Company trading post at Fort Rupert by rowboat in 1904. The couple was bound for Hardy Bay in windswept Goletas Channel, about 30 kilometres north of present-day Port McNeill, along a wild and sparsely settled coast. Alexander had taken a liking to the sheltered anchorage fed by the Quatse and Tsulquate rivers at the north end of Vancouver Island. The bay had been named by an equally admiring George Richards, captain of HMS Plumper, to commemorate Vice Admiral Thomas Masterman Hardy, who was captain of Lord Nelson’s flagship HMS Victory at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1803. Sarah was one of the tough, resilient daughters of Robert Hunt, who had been a fur trader at Fort Rupert for 20 years before buying the post outright in 1883, and Mary Ebbetts, a Tongass Tlingit woman from the North Coast. And although Sarah was pregnant and approaching term, she didn’t hesitate to accompany her husband on the long row to their new home. On landing, however, she slipped on the wet stones and went into premature labour. Alexander got her up into the one-room cabin he had built, then set out to get the nearest doctor from the Anglican mission in the village of Alert Bay, about 35 kilometres to the south. Rowing like a demon, he made it as far as Fort Rupert when a storm blew up and drove him ashore with many kilometres of heavy seas still separating him from the doctor on Cormorant Island. His mother-in-law, however, called on her relatives in the emergency and a sea-going canoe sped him the rest of the way through heavy weather to get the doctor and then bring him back up the coast to Hardy Bay. When Alexander and the doctor returned, they found Sarah lying on the floor of the cabin. She was exhausted but otherwise all right. Cradled in her arms was newborn Douglas Lyon, the first citizen of what would become Port Hardy, the commercial and industrial hub of northernmost Vancouver Island. |

Few of these cross-cultural relationships, however, had the impact on BC’s history that Amelia’s marriage to James Douglas was to have. In 1828, young James was temporarily in charge of Fort St. James when he apprehended a man wanted for the murder of two Hudson’s Bay Company traders five years earlier at Fort George. Unfortunately, the suspect was killed when he tried to stab Douglas with an arrow. Even worse, the rash young clerk had gone into the house of the Carrier Chief Kwah to make the arrest. By violating the chief’s prerogative to offer sanctuary he had caused the chief to lose face. Kwah seized the fort, overpowered Douglas and was preparing to kill him with a knife when Amelia intervened. She began throwing bales of recently arrived trade goods at the feet of the Carrier chief and his warriors. Kwah accepted them and, his honour satisfied, released his captive. Amelia’s marriage to the hotheaded Douglas was to last 49 years and produce 13 children. She would have a private audience with Queen Victoria. And if her life ended in the tranquil obscurity she sought, it might also be argued that her legacy is the province itself, for without her understanding of Kwah and her calm diplomatic solution, British Columbia might never have come to pass.