Fishing, Aboriginal

FISHING, ABORIGINAL, predates the arrival of Europeans in BC by many centuries. FIRST NATIONS on the coast and in the Interior relied on many different types of marine plants and animals as traditional sources of food and as trade goods. Coastal people had access to a wide variety of marine resources, including SALMON, different types of GROUNDFISH (HALIBUT, LINGCOD, ROCKFISH and others), shellfish (ABALONE, CLAMS, SEA URCHINS, CRABS and others), STURGEON, EULACHONS, HERRING and herring roe. Historically, WHALING and the harvest of marine mammals such as SEA OTTERS, SEALS and SEA LIONS were also important, and many marine plants and animals were used in the making of tools, weapons, medicines and other items. Interior groups inhabiting the inland watersheds were particularly reliant on the salmon that migrate up the province's many rivers and streams to spawn. Using a variety of ingenious weirs, traps, nets and spears, the First Nations intercepted the salmon on their migration paths. When the first FUR TRADERS arrived in the region early in the 19th century, they relied on salmon caught by the First Nations to provision the trading posts, and ultimately as an item of trade in its own right. Salmon became so important a commodity in the frontier economy that it was accepted as a form of currency.

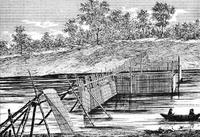

The establishment of SALMON CANNERIES at the mouth of the FRASER R in the 1870s marked the beginning of the Euro-Canadian commercial fishery in BC (see FISHING, COMMERICIAL). Initially the commercial fishery relied on local aboriginal labour, with the men employed in fishing and the women in processing. As competition for the resource became acute, the Canadian government severely restricted the upriver weir and trap fisheries of the aboriginal groups. Government fishery managers, concerned first and foremost with the interests of the canners, decided to protect the Euro-Canadian fishery at the expense of the aboriginal fishery. Regulations introduced in 1888 confined First Nations to a "food fishery" for their domestic use and prohibited them from selling salmon. They were also prohibited from using their efficient traps and weirs and confined to less efficient fishing methods (see BABINE BARRICADES). These prohibitions were most serious for First Nations inhabiting the watersheds of the 2 great salmon rivers, the Fraser and the SKEENA; most of them lived too far from the ocean to join the commercial fishery, in which many coastal aboriginal people participated. Indeed, aboriginal fishers have always comprised a significant portion of the regular commercial fishery; since the early 1900s about one-third of the BC commercial fleet has been owned and/or crewed by aboriginal fishers. However, a series of developments in the commercial fishery during the 20th century, and especially after WWII, conspired to reduce the participation of aboriginal people.

At the same time, the food fishery was also in decline as industrial developments and government regulation tended to compromise the aboriginal economy. This trend began to be reversed in the 1990s, however. First Nations have a constitutional right to fish for food and for social and ceremonial purposes in accordance with Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982. The aboriginal right to fish for these purposes is second in priority only to conservation. This right was confirmed by the Supreme Court of Canada in the 1990 SPARROW DECISION. Demands by First Nations for greater access to the resource have been part of the land claims process (see ABORIGINAL RIGHTS), pursued in part by court appeals and in part by negotiations in the ongoing treaty-making process that began during the 1990s. The NISGA'A TREATY, for example, contains important fisheries provisions. In response to the Sparrow decision, the federal government, which has jurisdiction over the salmon fisheries (see FISHERIES JURISDICTION), implemented the Aboriginal Fisheries Strategy (AFS) in 1992. In agreements with a number of First Nations, the government started to allocate more fish to the aboriginal food fishery. The sale of fish from these negotiated allocations was also permitted. In return, aboriginal groups agreed to a negotiated cap on the amount of fish allocated to them, which helped to restore government control over aggregate catch levels. The AFS was opposed by many stakeholders in the commercial fishery on the grounds that the government was creating a separate fishery based on race, but in general the policy was intended to enhance aboriginal participation in the province's fisheries. At the end of the 20th century, aboriginal food fisheries were estimated to account for about 8% of the total fish catch in BC.