History of BC

Human beings have inhabited the place we call British Columbia for about 10,000 years. Unfortunately, far less information survives about the early centuries than about the last two. Men and women did not leave the kinds of records making it possible to reconstruct their lives in more than the broadest outlines. It was the arrival of newcomers with a penchant for record keeping that is usually seen to mark the beginning of the "history" of BC. The name BRITISH COLUMBIA is itself an artifact emanating out of these last 200 years. Apart from the Pacific Ocean to the west and the ROCKY MTS to the east, the place BC is as much constructed as is the "history" that we attribute to it. All the same, some boundaries, both literal and illusory, are essential to any story. BC has existed as a political entity—and increasingly also as an economic and social unit—only since the 1860s.

Some aspects of the lives of aboriginal peoples prior to the European intrusion are generally known (see FIRST NATIONS). A broad division existed between peoples living along the coast and those inland. The generally harsh nature of the Interior terrain meant that people there had to spend much of their time obtaining food and shelter. For the most part they did not develop the complex social organization and rich ceremonial life associated with coastal people, who lived in a more bountiful environment symbolized by the 2 basic staples of SALMON for food and CEDAR for most everything else. Coastal peoples divided the year into 2 parts, the summer given over to securing a livelihood and the winter to cultural and spiritual activities. At their heart lay the POTLATCH, a highly regulated ceremony at which goods were distributed to confirm or assert status or to commemorate important events. The complexities of tribal groupings across what is now BC are indicated by the existence of 30 different languages, each as distinctive from the others as is English from German (see also FIRST NATIONS LANGUAGES).

Exploration and Fur Trade

BC's location on the far edge of N America kept it from being visited by Europeans long after most other areas of the world were claimed by them. It was Russian exploitation of present-day Alaska to the north and Spanish colonization of Mexico to the south that brought the first intrusions. Vitus Bering, a Danish sea captain in the Russian naval service, may have reached as far south as BC during a 1740 expedition intended to determine whether N America was a separate continent from Asia. Spanish expansion resulted in 3 expeditions between 1774 and 1779, which nominally claimed the coast for Spain. Britain had long sought to locate a water route, a Northwest Passage, to facilitate its lucrative trade with Asia. Attempts to do so from eastern N America failed, and so the English national hero Capt James COOK was dispatched to find a route inland from the West Coast. Cook anchored near NOOTKA SOUND on the west coast of VANCOUVER ISLAND in the spring of 1778 and then sailed north along the coast before turning away toward Asia. Although he did not find a Northwest Passage (not surprisingly, since none existed), his voyage had 2 important consequences. Most immediately, Cook's expedition triggered the first economic intrusion into the Pacific Northwest. His men acquired a few SEA OTTER pelts in trading with local people, and these found a ready market in China. A maritime FUR TRADE quickly developed in which New England merchants from the newly independent United States soon beat out their competitors. More than 170 ships from several countries visited the coast during the peak years of exploitation between 1785 and 1825, by which time the sea otter was essentially trapped out. The future BC's first resource-based boom collapsed, much as would a series of others over the next 2 centuries. The second consequence of Cook's visit was a growing controversy with Spain over the sovereignty of Nootka, perceived as the entryway to the BC coast. A diplomatic resolution of 1790–94 gave trading rights to both countries without determining ownership. Each country sought to support its position by acquiring as much information as possible, and it was in this connection that Capt George VANCOUVER mapped much of the coast for Britain in 1792–94. Thereafter Spain turned its attention elsewhere (see also NOOTKA SOUND CONTROVERSY).

The future BC faced east as well as west. The first intrusions from this direction were by fur traders also in search of a water route, in their case one through which the NORTH WEST CO based in Montreal could take furs to market. In 1793 Alexander MACKENZIE travelled Interior rivers to the inlet at BELLA COOLA. In 1808 Simon FRASER reached the mouth of the river that bears his name, and David THOMPSON was exploring areas to the south at about the same time. Although none of these men located the much-sought water route, several small trading posts were established. The agreement ending the War of 1812 between Britain and the US established a loose joint occupation of the Pacific Northwest, which still did not much interest any country apart from the immediate economic advantages to be got from trading for pelts.

A land-based FUR TRADE developed in the early 19th century across the central Interior of today's BC, an area dubbed NEW CALEDONIA, and south to the COLUMBIA R in Washington and Oregon. In 1821 the HBC, based in London, took over the last of its rivals and thereafter managed the Pacific Northwest fur trade through a series of posts at which newcomers lived year-round while trading with local peoples for pelts. Overall this trade was a minor intrusion into aboriginal societies. Trade goods entered local economies and a few women cohabited with newcomers, but for the most part lives continued much as they always had. The fundamental shift for aboriginal peoples came when Europeans decided to stay and thereby to compete for land and resources rather than merely exploit a specific resource and then move on. This shift began in the 1830s, at a time when Americans increasingly believed they had a "manifest destiny" to occupy the continent from ocean to ocean. Trekking overland, American families settled near the principal HBC trading post of Fort Vancouver, sited near the mouth of the Columbia R, in such growing numbers that the HBC decided, in order to ensure its future well-being, to establish a new post on Vancouver Island to the north. FORT VICTORIA was built in 1843 under the supervision of an HBC fur trader named James DOUGLAS. Agitation by American settlers caused the US and Britain to sign the Treaty of Washington in 1846 (see OREGON TREATY), extending the existing international boundary of 49°N west from the Rocky Mountains circling around the southern tip of Vancouver Island to the Pacific Ocean.

The Treaty of Washington not only gave the future BC its southern boundary, it ceded the territory to Britain. In 1849 Britain officially colonized Vancouver Island. A governor, Richard BLANSHARD, was appointed, but that was about all. Britain was not much interested in this remote corner of N America, and handed over everyday administration of its new possession to the HBC on condition that it encourage colonization. The HBC moved its centre of operations north to Fort Victoria, put James Douglas in charge, and gradually closed its posts in American territory. On Blanshard's departure in 1851, Douglas took on the additional responsibility of governor, which ensured that the links would remain close between colony and fur trade. In practice, as Douglas recognized, "the interests of the Colony, and the Fur Trade will never harmonize." To the extent that newcomers took up land, they altered the existing order of things, making it less likely that local First Nations would continue to collect furs. The HBC's encouragement of colonization was never more than lukewarm, the minimum needed to keep the British government from revoking the agreement. The HBC did get into the business of mining COAL, and brought over a handful of English miners to settle at NANAIMO. The few newcomers and the unwillingness of Great Britain to spend much money on its fledgling colony meant that little attention was given to making treaties with aboriginal people. Douglas did negotiate 14 small treaties covering the area around VICTORIA and the coal mines in the years 1850–54, but thereafter lacked the resources to do more (see DOUGLAS TREATIES). Britain became briefly interested in Vancouver Island with the outbreak of the Crimean War in 1854, whereupon its Royal Navy contingent stationed on the west coast of N America was moved north from Chile to ESQUIMALT. As of 1855 the non-aboriginal population of Vancouver Island did not much exceed 700, with another handful at the various posts scattered across the mainland.

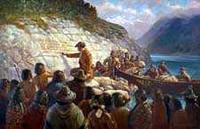

The Gold Rush

There matters stood until news leaked out in 1857 of the discovery of GOLD in sandbars on the FRASER R. The gold rush of 1849 to California had transformed that territory, only recently acquired by the US from Spain. Now it was BC's turn. The first newcomers to make it north to Victoria in the spring of 1858 were almost all experienced miners and merchants. As news spread, others came from farther away, including the US, Great Britain and China. Some estimates put the number at 30,000 in 1858 alone, followed by additional thousands over the next 6 years. Most men—and they were almost all men—left almost as soon as they came, for the difficulties of getting to the goldfields were enormous. New finds moved up the Fraser River north into the CARIBOO, meaning that travel was never easy. By 1865 the early trails relying as much as possible on water gave way to the newly constructed CARIBOO WAGON ROAD, which extended north to the boom town of BARKERVILLE. The GOLD RUSH made it imperative that authority be regularized. The long time it took to communicate with Great Britain forced James Douglas to act largely on his own initiative to establish control over the goldfields. His actions were confirmed by Britain's decision to declare the mainland a separate colony of British Columbia on 2 Aug 1858, the name being selected personally by Queen Victoria. Douglas was given the additional responsibility of governing the mainland colony on condition that he sever his HBC ties. Great Britain sent out a contingent of ROYAL ENGINEERS to construct basic infrastructure and, for strategic reasons, they selected NEW WESTMINSTER on the north bank of the Fraser R as the mainland colony's capital. Vancouver Island became wholly a British colony on 30 May 1859 when the HBC lease expired. In 1863 BC's present BOUNDARIES were essentially put in place when, following the discovery of gold in the far north, Britain asserted the mainland colony's sovereignty north to 60° and east to the 120th meridian.

Colonial Government

Much like other British possessions around the world, the two colonies were governed by a combination of appointed and elected men (see COLONIAL GOVERNMENT). A legislative assembly with 7 elected members existed on Vancouver Island from 1856, together with an appointed council that had to approve all laws enacted. At first BC had no legislative bodies whatsoever, likely because Britain lacked confidence in its largely transient MINING population. In 1863 the mainland colony was granted a legislative council intended to have a gradually increasing proportion of elected as opposed to appointed members. The minority eligible to participate in political life by virtue of being male, British subjects, and property holders divided on several bases. Newcomers, particularly those from within British North America, resented the privileges enjoyed by senior officers associated with the HBC, whose position was buttressed by more recent arrivals from Britain to staff the colonial bureaucracies. Douglas was accused of favouring their interests, as well as that of Vancouver Island over the mainland. The 2 principal protagonists were Amor DE COSMOS, a Nova Scotian, in Victoria and John ROBSON, an Ontarian, in New Westminster, both of whom used the NEWSPAPERS they edited to make their points.

On Douglas's retirement in 1864, Britain appointed separate governors to the 2 colonies. They were replaced by a single governor in 1866, when the colonies were joined into the United Colony of British Columbia. The decline of the gold rush had decreased governmental revenues whereas the construction of the Cariboo Wagon Road left a large debt. Victoria became the capital of the new colony, but it was the mainland's legislative council, mostly appointed, that replaced Victoria's elected legislative assembly. BC's long-term status became much debated. The contingent allied with Britain was content with the existing situation, whereas newcomers from within British North America looked to entry into the new Dominion of Canada, created in 1867 (see also CONFEDERATION). The lack of representative and responsible government was deemed unacceptable. Yet others sought annexation to the US. Relationships with the self-confident nation to the south had never been easy. In 1859 disagreement over the location of the "main channel" dividing Vancouver Island from the US had led to an open confrontation over SAN JUAN ISLAND, dubbed the PIG WAR. The matter was sent to an arbitrator, who eventually awarded the island to the Americans. In 1867 the expansionist US purchased Alaska, making it appear almost inevitable to some that the British colony would become its next possession. A leading BC politician, John Sebastian HELMCKEN, later recalled how local Americans "boasted that they had sandwiched B. Columbia and could eat her up at any time!!!" Sympathetic merchants in Victoria prepared 2 petitions requesting annexation and sent them to the US Congress, which debated the matter briefly. It was likely the presence of the Royal Navy base at Esquimalt that kept Britain from bargaining away its remote and not much wanted possession.

Britain favoured BC's becoming part of Canada and in 1869 named a new governor, Anthony MUSGRAVE, with a mandate to achieve that option. The handful of men who dominated local politics had to be convinced, and the formal proposal that Musgrave cajoled out of the legislative council in Apr 1870 contained such bold demands for entry into Confederation that they were considered likely to be rejected. It was events elsewhere that caused them to be accepted. Britain had already arranged for the large territory located between BC and Ontario that was loosely under HBC supervision to be transferred to the new Dominion. Canada's control over the fur trade colony at Red River, which became the province of Manitoba in 1870, was soon challenged by local Metis under the leadership of Louis Riel. These factors made the BC delegation's demands that a wagon road be built and that Canada pick up the colony's large debt and assume a larger population base for future per capita grants than actually existed, appear not preposterous but quite reasonable. The wagon road was even upgraded to a railway to be constructed within the decade, as much to ensure control over the prairies as to appease BC. The delegation had no choice but to accept the terms of union, and on 20 July 1871 BC joined the Canadian Confederation.

BC Joins Canada

The British North America Act that had created Canada in 1867 was extended to BC. The Act was intended to ensure a strong central government. Only matters considered of local significance were left to the provinces, including health and education services, maintenance of law and order, development of physical infrastructure, and management and sales of public Crown lands. BC received 3 seats in the Senate and 6 in the House of Commons, the small numbers being diminished further by the distance, both real and psychological, that then and thereafter separated the far west province from the capital at Ottawa. As a rule, BC's representatives did not distinguish themselves at the federal level or rise to national prominence. Shortly after entry into Confederation, elections were held for members of Parliament and for the 25 members of the new provincial legislature. The Canadian gov gen, acting on behalf of the British Crown, appointed a LT GOV for BC. It was his obligation to request one of the elected MLAs to form a government and so become PREMIER. The concept of responsible government was formally acknowledged when the first premier, John Foster McCREIGHT, resigned after losing a non-confidence vote in the legislature. McCreight was replaced by Amor de Cosmos, a long-time political activist, and then by a sequence of men selected not as leaders of parties, which did not yet exist in BC, but as heads of loose, shifting coalitions of like-minded persons. The legislature's representative character was restricted in 1874 with the removal of the franchise from CHINESE and aboriginal people, but was extended 2 years later, so far as male British subjects were concerned, by removing property holding as a requirement for voting. Overall the provincial government was a fairly passive affair, apart from dispensing patronage and encouraging resource exploitation. A system of free non-denominational elementary schooling was enacted in 1872, but little else was done in the way of social services.

The relative ease with which political structures became responsible and representative, from the perspective of white males, obscured the fragile demographic and economic bases of the new province. Alongside 25,000 or more aboriginal persons, 1,500 Chinese and about 500 BLACKS were just 8,000 whites. Not surprisingly, given the character of the gold rush, 3 out of every 4 non-aboriginal adults were men. Even though the availability of land gave newcomers a reason to stay, many soon discovered that multiple occupations were necessary in order to survive economically. Gold and coal were mined and some lumbering went on (see also LOGGING), but for many their principal interest lay in waiting for the railway with its promise of prosperity. The impact of entry into Confederation fell on aboriginal peoples, perhaps more than on any other group. As governor, Douglas had expressly prohibited the pre-emption of aboriginal settlements, but in practice the situation became chaotic once the gold rush erupted. Waves of European disease, and in particular a devastating SMALLPOX epidemic in 1862–63, led to sharp numerical decline even as social Darwinian notions of "survival of the fittest" convinced many newcomers that indigenous populations were in any case destined to disappear. Under the terms of the BNA Act, responsibility for aboriginal peoples was transferred to the Dominion government when BC joined Canada. According to the terms of union, they would be treated as generously as had previously been the case. In practice it was the interests of newcomers that won out. Aboriginal peoples were increasingly confined to small, remote RESERVES even as no more treaties were signed, or indeed even contemplated. The sole exception was TREATY NO 8, one of several numbered treaties negotiated by the federal government on the prairies; it was signed in 1899 and included the northeast region of BC.

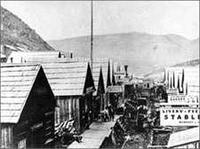

Construction of the promised rail line was repeatedly postponed for political and financial reasons. In 1878 Prime Minister John A. Macdonald launched a new National Policy intended to encourage economic development through higher tariffs, immigration and a transcontinental railway. The National Policy echoed the imperialist sentiment of the day in viewing the role of the periphery, be it colonies or western Canada, as strengthening the economy of the centre through providing raw materials to be returned as manufactures. Not only did value added in the form of jobs and industrial growth rightfully accrue to the centre (Ontario and Quebec), but the imposition of differential freight rates and tariffs on manufactured imports ensured that the periphery would not develop independent of the centre. While detrimental to BC over the long term, the National Policy did get rail construction underway. The Montreal syndicate that won the right to build the CPR received considerable government assistance, including large land grants. Much of the labour was provided by Chinese, over 15,000 of whom entered the country through Victoria for that purpose. The syndicate sought to maximize profits by putting the western terminus in a location where the best land could still be had, and so chose BURRARD INLET. With the arrival of the first scheduled passenger train on 4 July 1886, the small lumbering community at GASTOWN was almost overnight transformed into the new city of VANCOUVER. Britain now lay just over 2 weeks away, and very soon the CPR extended its reach west to Asia by steamship. In little more than a decade Vancouver replaced Victoria as the province's principal commercial centre and port through which goods moved to world markets. Stops along the new rail line also quickly developed into communities, as at KAMLOOPS and REVELSTOKE.

Growth of a Resource Economy

The CPR energized the province's economy, whose base in natural resources was consistent with the National Policy. Lumbering continued apace. COAL MINING grew on Vancouver Island and gold mining still went on across the Interior. Hard rock mining expanded into the KOOTENAY. SMELTERS proliferated, notably at TRAIL in the W Kootenay. A new industrial process permitting very thin, uniform sheets of metal to be rolled out made possible the canning of salmon, an abundant resource that had not yet been much exploited. Soon seasonal canneries, largely financed by external investment, dotted the coast (see SALMON CANNING). Salmon from BC became a staple of many British households. The paucity of arable land meant that AGRICULTURE never acquired the hold it exercised elsewhere in Canada, where at least half of all employed males were working in agriculture. In BC the proportion was less than 1 in 5. Another effect of the railway was population growth. The line encouraged migration from within Canada, with which the province now for the first time had a direct link. The number of BC residents born elsewhere in Canada mushroomed from 3,500 in 1881 to 20,000 by 1891. The Chinese who had helped to construct the new line were not, as promised, provided transportation back home. Many put down roots where last employed, others made their way to the CHINATOWNS that were growing up in Victoria, Vancouver and other communities. The number of residents born in Asia approached 10,000 by 1891 and doubled by the end of the century. The province's population rose from about 50,000 in 1881 to 100,000 a decade later and almost 180,000 by 1901. See also PEOPLES OF BC.

BC's growth as a settler society altered provincial politics. The number of eligible voters rose sharply from about 3,000 in the mid-1870s to 44,000 in the 1900 election. Provincial life was more impersonal, making it less acceptable to be governed by small cliques and by premiers whose prestige rested on personal contacts who tended to reward their friends in order to stay in power. By the end of the century, ministries fell so quickly that potential investors were being scared away. The introduction of party labels, such as existed elsewhere in Canada, began to be discussed. One of the enthusiasts was young Richard McBRIDE, a lawyer born in New Westminster. McBride was elected an MLA in 1898 and became premier in 1903 under the banner of the CONSERVATIVE PARTY. When his opponents banded together as LIBERALS, also in emulation of federal practice, political parties became a fact of life in BC. Previous premiers had held office at most 3 or 4 years before being replaced by the next clique; McBride broke the pattern by remaining in charge for 12 years. He inherited a large provincial debt and considerable doubt as to the province's future course. Many British Columbians, including McBride and the Conservatives, considered that the ordinary business of government could not be carried on under the terms of union with Canada. The province's size, difficult terrain and scattered population made for exceptionally high routine costs of administration. A lack of manufacturing obliged BC to buy goods from central Canada at highly protected prices, whereas the province's chief products—minerals, fish, timber—had to be sold in world markets in direct competition with all other nations. McBride sought "better terms" with the federal government. The compromise that was reached provided a short-term annual subsidy in exchange for the provincial government raising taxes and reducing expenses in an attempt to balance the provincial budget. The apparent ease with which the quest for "better terms" resolved itself was deceptive, for BC was entering another of its periodic boom periods. Across Canada and beyond, economies were expanding. Growing world demand for BC commodities obscured the fundamental issue of the province's status in Confederation. McBride soon became caught up in the new spiral of growth. Keen to open up more of the province to resource exploitation, he encouraged rail construction and financially supported the CANADIAN NORTHERN and Pacific Great Eastern lines (see BC RAIL). As well, the federal government subsidized a second transcontinental line, the GRAND TRUNK PACIFIC, which opened up the prairies and then the BC central Interior to agricultural settlement. PRINCE RUPERT got its beginnings as the western terminus of this new line.

Complementing the provincial government's encouragement of rail construction was its promotion of external investment. The capital that could be generated within BC was extremely limited, so expansion came primarily through outside impetus, as had already occurred with salmon canning and mining. Two Ontarian entrepreneurs, William Mackenzie and Donald Mann, were particularly active, not only in rail construction but also in coal and lumbering. Both Britons and Canadians engaged in land speculation, in which parcels oftentimes located near the new rail lines were divided into small plots and sold to newcomers. Irrigation transformed the interior OKANAGAN VALLEY from ranching (see CATTLE INDUSTRY) to small-scale fruit growing. British pounds entering BC tended to be unobtrusive, many taking the form of portfolio investment in government-guaranteed bonds underwriting new physical infrastructure or public utilities. American dollars expanded the COPPER industry in the Kootenay and Boundary regions and financed a large PULP AND PAPER mill on the South Coast at POWELL RIVER. American investment also caused lumbering to grow phenomenally, in part because the allocation of timber leases on Crown land long remained unregulated. By the time a provincial Royal Commission finally raised the alarm in 1910, about 80% of FOREST land owned by the Crown had been leased, mostly to large syndicates (see FOREST POLICY). Boom conditions were fuelled by population growth. As part of the National Policy, the Dominion government in 1896 launched an immigration campaign intended to attract the agricultural settlers needed to produce raw materials and purchase manufactures. BC also benefited. Britons in particular found the province attractive, in part because of its earlier colonial status. The number of British-born grew from just 6,000 in 1881 to 116,000 by 1911. BC's population more than doubled in the first decade of the 20th century to almost 400,000, and swelled to half a million by the beginning of WWI, which effectively curtailed large-scale immigration into Canada until mid-century. BC, alone among the Canadian provinces, continued to attract immigrants from Asia because of physical proximity. SIKHS from India often arrived with lumbering experience and tended toward that occupation, just as JAPANESE were most likely to become fishers or small-scale farmers. The number of British Columbians born in Asia approached 30,000 by WWI. In sharp contrast, numbers of aboriginal men, women and children declined to a nadir of 20,000 by 1911. The racism that confined aboriginal peoples to reserves and their children to segregated schools affected all newcomers who were perceived to be non-white (see also RESIDENTIAL SCHOOLS). Provincial disenfranchisement was extended in 1895 to the Japanese and in 1907 to East Indians (see SOUTH ASIANS). The number of Japanese allowed to enter Canada—in practice, BC—was restricted by a "gentleman's agreement" between the 2 countries. Chinese immigration was initially controlled through a HEAD TAX on new arrivals and then, in 1923, legally prohibited by the federal government. The KOMAGATA MARU incident in 1914 symbolized the commitment of politically and economically dominant groups to a "white" BC.

The benefits of growth were increasingly filtered through Vancouver, which acted as service centre to an ever-expanding hinterland, one that eventually encompassed almost the entire province. By 1911 almost half the population lived in the Lower Mainland region extending from Vancouver through the FRASER VALLEY. Wherever British Columbians resided across the vast province, the tremendous expansion of capitalism during the early 20th century had an enormous impact on their lives. Changing patterns of residence and employment heightened, and made more visible, inequities in conditions of work and quality of life. Agitation for reform extended from the workplace into the home. The nature of resource exploitation threw men together in work that was often tedious, dirty and hard, and at the same time poorly paid. As early as 1877 coal miners went on strike on Vancouver Island after the mine owner, Robert DUNSMUIR, cut their wages by a third. The ruthlessness with which the men were forced back to work, with the co-operation of the provincial government, set a pattern for employer–employee relations in BC. While some workers sought change through the ballot box, direct action held greater appeal. Membership in trade unions reached over 22,000, or 12% of the non-agricultural LABOUR FORCE, by 1911. During these years more strikes broke out in BC than in any other province (see also LABOUR MOVEMENT). Activism was not confined to men or to the workplace. The movement for social reform was a largely female, white, middle-class enterprise in which women's traditional role within the home was extended outward to the community. Their authority to do so was sanctioned by the Protestant churches, which increasingly felt under an obligation to improve this world as well as prepare their adherents for the next one. Two of the issues that most agitated social reformers, in BC and more generally, were temperance and WOMEN'S SUFFRAGE. The first branch of the Women's Christian Temperance Union began in Victoria in 1882 and the first suffrage association was formed in 1910. Sensing the winds of change, the opposition Liberals backed female suffrage 2 years later.

From World War to Depression

Even as reform was gaining impetus, the economic boom ran its course. By 1912 those with capital were pulling back in the realization that much of the dynamism was little more than the rhetoric of boosterism. The political situation in Europe was deteriorating, culminating in Britain's declaration of war against Germany in Aug 1914. The war affected everyone as patriotism became the order of the day. BC had the highest per capita volunteer rate in Canada at just over 90 per 1,000 population. The province's uneven sex ratio played a role, as did its renewed British ethos. British Columbians of every background volunteered for service, including members of the province's aboriginal, Japanese and Sikh communities, and they all contributed to the successful conclusion of the war in 1918 (see also MILITARY HISTORY). It was during the war that McBride's premiership finally ended. A combination of factors, ranging from his ill health to charges of patronage and corruption, brought his resignation at the end of 1915. Within months his successor went down to defeat by the Liberals, which then governed for 12 years. The most significant of the 3 Liberal premiers was John OLIVER, who held office from 1918 to his death in Aug 1927. Oliver's long tenure rested as much on internal dissension within the opposition Conservatives as it did on his image as a self-made sage. In 1922 a right-wing splinter group led by Vancouver businessmen joined with dissatisfied farmers to attempt a return to the older coalition style of politics. Their choice of name, the PROVINCIAL PARTY, pointed up their dissatisfaction with the mainstream parties, which they viewed as a federal imposition. The change in ruling parties from Conservative to Liberal worked to the advantage of social reformers. The patriotism unleashed by the war led to women being given the right to vote in Manitoba in 1915, and the other prairie provinces followed in short order. The provincial Liberals made PROHIBITION and suffrage part of their successful 1916 election campaign. The ballot included referendums on both issues, which were approved. Legislation soon followed to prohibit the sale of liquor and to give women the right to vote provincially and to be elected to the legislature. The first female MLA was Mary Ellen SMITH, who in 1918 ran in a Vancouver by-election to succeed her late husband. WWI also set the stage for what in retrospect can be seen as the culmination of labour's thrust of the previous2 decades. Unrest became widespread, particularly after the federal government enacted conscription legislation in 1917. The concept of One Big Union, a single organization of all workers, was gaining appeal even as a general strike broke out in Winnipeg in May 1919. Support was widespread for both initiatives across BC, but neither succeeded. Within the year it became clear to most observers that the brute power of the state in support of capitalism was superior to that which could be marshalled by workers, even under favourable conditions. Trade unions continued to exist across BC but the movement as a whole became fragmented by issues of personality and race. The limits to reform of the workplace were paralleled in social activism in the case of Prohibition. The law was openly flouted, and in 1920 a Prohibition plebiscite passed. The first English-Canadian province to repeal Prohibition, BC became the source of much of the liquor smuggled illegally into the US before it too finally repealed its legislation in 1933 (see also RUM-RUNNERS). On the other hand, the Liberal government had caught the reform mood and enacted a spate of legislation that created a civil service, initiated workmen's compensation, provided for neglected children, gave pensions to needy mothers, established public LIBRARIES and expanded public schooling. The limit to reform, in or out of the workplace, was its equation with the dominant society to the almost total disregard of aboriginal and other non-white British Columbians.

The war's end in 1918 did not return BC to its earlier economic self-confidence, but rather heralded a recession across the western world that only lifted in 1923. BC's considerable growth during the remainder of the decade built on existing strands in the province's development. International demand for staples, particularly lumber and minerals, once again set the pace. The Panama Canal, which opened in 1914, made Vancouver an important transshipment point for a wide range of commodities. These included not only products from BC but also prairie grain previously sent east by the CPR. By the end of the decade, fully 40% of Canada's grain exports were going through Vancouver. BC's economy still depended on the vagaries of international markets, which collapsed following the stock market crash of Oct 1929. What first appeared to be only another recession soon became a full-blown depression. The phenomenon had world-wide causes and consequences, but that in no way diminished the effect on individual British Columbians. Every component of the economy moved down. Net value of production fell by almost 60%. So did exports of Canadian products from BC, including prairie grain. Almost all wages fell. Vancouver was hard hit, in particular elderly people and residents of modest means. Initially provincial politicians seemed unable to grasp the seriousness of the Depression. The Conservatives returned to power in 1928, due not as much to their better policies as to the force of personality. Simon Fraser TOLMIE, like his predecessor Richard McBride, had strong roots in BC. Descended from HBC fur traders, he had been an MP and federal minister of agriculture. The Conservatives promised "the application of business principles to the business of government," which rebounded to their disadvantage once the Depression hit. By 1931, when unemployment reached 28%, the highest in Canada, Tolmie was finally forced to act. RELIEF CAMPS were set up, mostly at remote locations safely out of sight of the general populace, where single unemployed males built ROADS and other public facilities in exchange for room, board and a small cash payment. The next year the federal government took over the relief camps, which eventually housed 8,000 men in over 200 camps. The Conservative party became entrapped by its commitment to "business principles." In 1931 Tolmie acceded to the request of a deputation of Vancouver businessmen that he establish a committee to propose solutions to the increasingly desperate financial situation. The KIDD REPORT, issued in 1932, recommended such sharp cuts to social services that mainstream British Columbians were enraged. They had come to expect more from their provincial government than its traditional functions of maintaining law and order, providing physical infrastructure and encouraging private enterprise. The growing sentiment in favour of more government was reflected at the national level, when in 1932 a new political party, the CO-OPERATIVE COMMONWEALTH FEDERATION, was established. The CCF brought together reformist strands in Canadian society with the goal of forming a socialist government by democratic means.

The next provincial election in 1933 was won handily by the Liberals, who captured 42% of the vote. The principal opposition came from the newly formed CCF with fully 32% of the vote. It was once again the force of personality that made the difference. The new premier was Duff PATTULLO. As well as having a strong hinterland base as a Prince Rupert businessman and mayor, Pattullo exuded self-confidence. The Liberal Party, long identified with social reform, now also committed itself to a more activist role for the state in dealing with social inequalities and unbridled capitalism. The CCF's shadow may have spurred on the enactment of legislation reforming taxation, restoring social programs and initiating public works. Pattullo's background led him to look northward at the immense area of the province that was still largely an aboriginal preserve, in the hopes of initiating economic development. Depressed conditions persisted, intensified in BC by unemployed men from across Canada who drifted west in the belief that at least they would not freeze to death. Often "riding the rails," they tended to congregate in "jungles," communities along the tracks, and repeatedly protested their circumstances. So did men dissatisfied with their lot in the relief camps, who were prone to march through Vancouver. In the spring of 1935, after getting no federal government response to their demands, unemployed men began a mass trek to Ottawa. The ON-TO-OTTAWA TREK, by then 25,000 men strong, was halted in Regina, where a riot ensued after negotiations broke down. These events finally persuaded the federal government to act. Nonetheless, numbers of unemployed grew in BC, and after the provincial government in desperation restricted relief to all but provincial residents, confrontation ensued on 19 June 1938, BLOODY SUNDAY, when about 1,000 jobless men occupying the Vancouver post office were forcibly evacuated. Pattullo increasingly came to believe that the province could only do so much and, like his predecessor Richard McBride, increasingly spoke out for "better terms" with the federal government. Federal acknowledgment of regional disparities came with the 1937 appointment of a Royal Commission on Dominion–Provincial Relations (the Rowell-Sirois Commission). Pattullo informed the commission in no uncertain terms that in 1938 "approximately 80% of the manufactured commodities imported into the Province of British Columbia is imported from Eastern Canada, while approximately 75% of our main primary products, apart from agriculture is sold in open competition in the world markets." Concluding in 1940 that disparities did exist, the commission recommended that the federal government exercise greater authority in relationship to the provinces. BC and some other provinces expressed their opposition, but by then WWII had intervened to postpone the debate.

World War II

The declaration of war in Sept 1939 once again put lives on hold, or so it seemed. The painter Emily CARR reflected in her journal how "war halts everything, suspends all ordinary activities." In reality the war initiated fundamental changes. The outbreak of hostilities finally ended the Depression. The value of production in BC doubled over the 6 war years. Manufacturing took off, owing particularly to SHIPBUILDING and aircraft construction. Northern BC was opened up dramatically after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in Dec 1941 convinced the Americans that a highway was essential for them to protect Alaska in case of attack. The BC portion of the Alaska Hwy ran from DAWSON CREEK through the PEACE R country in the province's northeast. Prince Rupert became an important supply centre for American bases. By the end of the war the north had, in a psychological sense, become part of BC. The war also brought a measure of political stability. In part to ward off the CCF, which won a plurality in 1941 although not the majority of elected of MLAs, the mainstream parties joined forces in a governing COALITION. Pattullo's strong advocacy of provincial rights contrasted sharply with a shift in public opinion toward a stronger federal government once the war broke out. Pattullo resigned in 1941, and the new coalition government was headed by Liberal leader John HART. The war put at particular risk Canadians of Japanese descent, almost all of whom lived in BC. After WWI many males had brought over "picture brides," women courted by correspondence and married by proxy. In sharp contrast to the declining numbers of Chinese and South Asians, British Columbians of Japanese descent numbered more than 22,000 by 1941. More than half were Nisei, born in the province and very much integrated into BC life. But in most people's minds there was little difference between Nisei and Japanese nationals, particularly as Japanese foreign policy became more aggressive during the 1930s. The province's geographical position made some people fear that British Columbians of Japanese descent, in particular fishers along the coast, might act against Canada's interests. Almost immediately after Pearl Harbor in Dec 1941, Canada declared war against Japan and, by federal action, seized some 12,000 fishing boats owned by residents of Japanese ancestry. A growing public outcry led first to male "enemy aliens" being rounded up, then to all persons of Japanese descent being expelled from the coast and from the Trail area, where the smelter was critical to the war effort. Men, women and children were sent to internment camps. Their property was sold off, sometimes far below fair value. About 4,000 evacuees, over half of them Canadian-born, accepted a federal offer to be repatriated to Japan. The others were only in 1949 allowed to return to the coast (see also JAPANESE, RELOCATION OF).

In sharp contrast to the treatment accorded British Columbians of Japanese descent, working people reaped the benefits of war. Full employment from 1941 accelerated the movement toward unionization, particularly in the FOREST INDUSTRY. Union membership among BC's non-agricultural labour force, which had reached a low of 7% in 1934, approached 30% by 1943. The next year the federal government established compulsory collective bargaining and the right of employees to form and join unions and the right to strike. By war's end in 1945, trade unions had become generally accepted by the population at large. WWII also brought some attention to aboriginal peoples. Individuals such as the Squamish chief Joe CAPILANO and groups like the NISGA'A had long spoken out for aboriginal rights to the land, but in general the dominant society had been unwilling to listen. Awareness now grew among veterans and others that aboriginal men had volunteered and fought valiantly in both wars, only to return home to segregation and racism. In 1946 the Senate and House of Commons established a Select Joint Committee to examine laws relating to aboriginal people. As recommended by its report, separate schooling (residential schools) gave way to children's attendance at the same schools as other British Columbians. The ban on the potlatch, which had never entirely kept aboriginal peoples from practising their traditional ways, was removed in 1951. So were prohibitions against political fundraising and the consumption of alcohol in public places. All the same, such measures were partial; for the most part aboriginal people remained confined to small reserves without the resources necessary to lead independent, self-confident lives.

Social Credit Era

As WWII drew to a close, many British Columbians feared another recession. Their worries were groundless: Canada entered a period of economic stability that with only a brief recessionary break from 1958 to 1962 extended into the early 1970s. The need to rebuild Europe, together with industrial expansion occurring around the world, increased demand for primary resources. BC was well placed to take advantage of economic opportunities. Forest industry activity expanded away from the coast into the central Interior, precipitating the growth of PRINCE GEORGE. OIL AND NATURAL GAS began to be exploited in the northeast, as it was on a larger scale in northern Alberta. The smelter at Trail was expanded, and ASBESTOS mining began in the far northwest. In 1951 the provincial government signed an agreement with the Aluminum Company of Canada (ALCAN) to construct a large smelter southwest of Prince Rupert at what would become the new town of KITIMAT. The next year the long-dormant Pacific Great Eastern Railway was finally completed to Prince George (later it was extended farther north). The province's capacity to capitalize on opportune economic conditions was enhanced by political realignment. The governing coalition continued after the war even as a new political force was emerging in the person of W.A.C. BENNETT. The consummate small businessman, Bennett rose to power under the banner of SOCIAL CREDIT, a populist political party that had originated on the prairies during the Depression, come to power in Alberta in 1935, and migrated westward as part of a movement of peoples. The number of British Columbians born on the prairies grew to over 1 in 5 by 1951. Among the newcomers was Bennett himself, a maritimer who moved first to Alberta and then to the Okanagan Valley. Unable to gain acceptance within the Conservative party, whose power base lay in the Vancouver establishment, Bennett was soon vitalizing BC's fledgling Social Credit movement. By the time of the provincial election of 1952, policy and personal differences had splintered the governing coalition. A transferable ballot had been put in place, intended to keep out the CCF, which was viewed as the common enemy. The result indicated how fully the 2 mainstream parties had fallen out of favour with voters. The CCF received the plurality of votes, but Social Credit ended up with one more seat. Called upon to form a government, Bennett made clear his sensitivity to the province's growing diversity by including in his cabinet the first woman to hold a portfolio, a trade unionist, persons of non-British descent, evangelical Christians, hinterland British Columbians and former Albertans. To resolve the political stalemate, Social Credit called a new election just a year later. The party benefitted from CCF disarray and won a decisive victory. In the next election, by which time the province had returned to a straight ballot, the Social Credit coalition was entrenched. The force of personality continued to be decisive even after the CCF reorganized itself federally in 1961 as the NEW DEMOCRATIC PARTY. Intended to be more moderate and inclusive, particularly of organized labour, the NDP proved incapable of getting more than a third of the popular vote, compared with Social Credit's 40–47%. Only in 1972, by which time Bennett had been in power a full 2 decades, did the balance shift.

Social Credit built on initiatives already underway and capitalized on generally rising wages, material prosperity and growing self-confidence existing across much of the western world. Much like his predecessors, Bennett also tended to blame the federal government for his failures and take personal credit for the successes. He promised British Columbians what he liked to term "the good life," and for a time he largely succeeded. Material progress through rapid resource development became almost a secular faith within Social Credit. The key to expansion lay in attracting large amounts of outside capital, and American dollars in particular arrived at unprecedented rates. By the mid-1950s over half the investment in a rapidly expanding forest industry came from the United States. A government policy favouring long-term leaseholders of Crown land as being more dependable and profitable encouraged corporate concentration. Much of the expansion centred on pulp, and this too encouraged the forest industry's consolidation into a handful of large integrated multinationals. The value of Canadian products exported from BC grew 5 times over the 2 decades from 1952 to 1972. A focus during the 1950s on infrastructure creation facilitated the big development projects, especially in HYDROELECTRIC power, that followed in the next decade. During the first 6 years of Bennett's tenure, more money was spent building roads than in the entire history of the province. Air and water transport also expanded during these years. The COLUMBIA RIVER TREATY signed in 1961 with the US initiated the construction of 3 storage dams in southern BC in exchange for a lump-sum payment by the US for the downstream hydroelectric benefits that would result. The Peace R in the northeast was harnessed with the construction of the BENNETT DAM. BC was finally becoming an integrated economic unit.

The more active role taken by the state extended into social services. Both the provincial and federal governments facilitated health insurance and special provisions for the young and the old in the form of family allowances and pensions. Educational opportunities became more equitable at the post-secondary level. A 2-year college was upgraded into the UNIV OF VICTORIA in 1963 and SFU opened in BURNABY 2 years later. COMMUNITY COLLEGES offering both vocational training and 2 years of university transfer courses were established around the province.

By the beginning of the 1970s, enthusiasm for Social Credit was finally waning. As it became obvious that even Bennett could not make the good times last forever, many had difficulty reconciling themselves to a harsher reality. In 1972 the NDP, led by David BARRETT, a youthful social worker, squeaked out a victory with 40% of the popular vote compared with Social Credit's 31%. The NDP immediately enacted numerous reform measures, which in retrospect can be seen as an attempt to do too much too fast during an economic downturn. The NDP government called an election in 1975, well before the end of its mandate, and was defeated by a revived Social Credit coalition headed by Bennett's son, William "Bill" BENNETT. The younger Bennett, who was identified with free enterprise and government restraint, headed a more austere administration than had his father. Under Bennett, then Bill VANDER ZALM and, briefly, BC's first woman premier, Rita JOHNSTON, Social Credit stayed in power as a free enterprise coalition until internal disorganization and lack of vision caused it to implode. A revived Liberal Party was unable to stop the NDP, which in 1991, led by Vancouver's popular former mayor Michael HARCOURT, narrowly won the provincial election with 40% of the popular vote. The NDP was returned to power in 1996 under Glen CLARK, despite losing out in the popular vote—39% to 43%—to the Liberal Party, led by former Vancouver mayor Gordon CAMPBELL and very deliberately non-aligned with its federal counterpart. In 2001 Campbell and the Liberals swept the NDP from power, winning 77 of 79 seats in the legislature. Four years later they won re-election, though with a much reduced majority.

From 1972 to the Present

It was not only politics that kept BC out of skew with the rest of Canada. A provincial economy based on natural resources, much as it had been since the first intrusions of outsiders, ensured an erratic pattern of economic growth. Shifts in world prices and in world demand rebounded as sharply as ever on provincial coffers. Vancouver continued to garner most of the benefits, although the provincial capital of Victoria and regional service centres of Kelowna, Nanaimo and Prince George all acquired their own much smaller hinterlands. It was increasingly evident that natural resources, whether lumber, fish or minerals, were finite. Moreover, attitudes toward exploiting these resources were shifting dramatically. The provincial government was repeatedly pressed into managing, protecting and conserving resources more actively. Particularly during Harcourt's tenure as premier, protection of the environment over the long term began to take precedence over immediate financial gain. TOURISM and the growth of the service sector moderated the situation to some extent.

Demographics also remained distinctive. Some newcomers had been permitted into Canada in the aftermath of WWII, but it was only in 1967 that a new federal policy once again encouraged immigration. Immigration, migration from elsewhere in Canada, and natural increase combined to put BC at the forefront of growth. By 1971 the province's population surpassed 2 million, having more than doubled since the end of the war. Over the next 3 decades it continued to grow, reaching almost 4 million by 2001. Unlike everywhere else in Canada, BC was still a province most of whose residents had been born elsewhere. It remained a land of newcomers who in adapting also refashioned the status quo. British Columbians who were Asian by descent once again became a sizable component of the province's population. The proportion born in Asia, which had fallen to 1% by 1961, approached 8% by 1991. Growing numbers of people from Hong Kong and elsewhere, many bringing with them considerable wealth and sophistication, erased forever the image of the Chinese as menial labourers. Their influence was particularly felt in the Lower Mainland, where most of them settled. As other British Columbians grew more tolerant, there were more opportunities for equality in all aspects of provincial life. In 1988 David LAM, a Chinese immigrant, was named the province's lt gov, and British Columbians of Chinese and South Asian descent were elected to public office both provincially and federally. No group of British Columbians occupied a more contradictory position than did aboriginal peoples. Social activism from the 1960s onwards contributed to a new dynamic, growing numbers. By 2001, 170,000 British Columbians, about 4% of the population, so described themselves. Land claims, more than any other issue, rallied aboriginal peoples (see ABORIGINAL RIGHTS). The lack of treaties in all but small parts of the province could no longer be ignored. Shortly before Social Credit lost power, the provincial government declared its willingness to negotiate in partnership with the federal government. The process of doing so proved to be enormously complex. The Supreme Court decision handed down in the DELGAMUUKW case at the end of 1997 and the signing of a draft treaty with the Nisga'a the next summer began, finally, to indicate the direction negotiations would take.

At the start of the 21st century BC remained as enigmatic a place as it had ever been. Provincial politics still depended more on personality and on populist coalitions than on loyalty to parties emulating their federal counterparts. Busts still followed booms as the province continued to rely on resource exploitation as the base of its economy. Not just politics and economics, but progressive approaches to issues of racial equality, continued to set the province apart even though newcomers of the past century and a half had not yet learned to live comfortably with BC's first peoples. Vancouver and the Lower Mainland dominated social and economic life much as they had throughout the century. Yet even the glitz of Vancouver, which is ever imagining itself a city-state on a world stage, could not disguise the province's increasingly fragile economic base. BC remained an exciting, if at times exasperating, place in which to live and work.

by Jean Barman