Chapter Eleven: “The world is my country . . .”

In July 1865, Schuyler Colfax, Speaker of the US House of Representatives, paid a visit to Victoria. During his stay he met rather ceremoniously with Mifflin Gibbs and US Consul A.H. Francis. Gibbs did most of the talking.

“On being introduced by the American Consul,” a newspaper account reported,

"Mr. Gibbs proceeded to say that they were happy to meet him and tender on behalf of the colored residents of Victoria their esteem and regard. They were not unacquainted with the noble course he had pursued during the great struggle in behalf of human liberty in the land of their nativity. . . . now that victory had perched upon the national standard—a standard henceforth and forever consecrated to universal liberty—they were filled with joy unspeakable.

"

Such sentiments were more than mere rhetoric. The United States, which Gibbs had once termed a despotism, was now committed to freedom and equality for all Black people. Those who had come as immigrants in 1858 were now beginning to feel like exiles. Many returned—in general, the less established and less successful. But many had put down roots in the British Northwest and had gained enough wealth to insulate themselves from White prejudice. The Black elite faced no threat of persecution, as they had in California.

Victoria’s social climate had also improved. If White colonists’ overtures had not increased, their provocations had at least lessened. The Victoria newspapers, once filled with stories and letters on racial issues, now let months go by without mentioning the Black residents. The attention might be a benign paragraph about a “Bachelors’ Pic-Nic” or the annual Emancipation Day celebrations—a pleasant contrast to inflammatory accounts like that of the “Cary-Franklin Jollification” back in 1860.

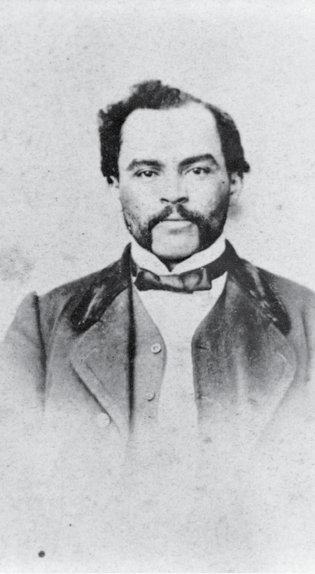

For Mifflin Gibbs, always eager for new challenges, Victoria must have been growing too safe and dull. In 1864 he had ended his long partnership with Peter Lester. Thereafter he seems to have earned his living from real estate, construction and investments. In November 1866 he ran again for city council in his home ward of James Bay—the most affluent in the city—and was elected. His council colleagues recognized his abilities, and as chair of the finance committee he wielded considerable influence. By the end of his first term he had paid off the municipality’s considerable debt, and in his second term he kept spending within the budget. He even served for a time as acting mayor.

His personal life was less successful. In seven years, Maria Gibbs had borne him five children. Now she took her children back to Oberlin, Ohio, leaving Gibbs alone in Victoria. The reasons for this separation are unknown. In his autobiography, Gibbs said very little about her and their marriage, but criticized himself as “a husband migratory and uncertain,” always following some new enthusiasm. It is also likely that Maria had come to dislike Victoria. Thanks to her years at Oberlin College, she was one of the best-educated women in the city. But her social life must have been limited, since White women did not mix with their Black neighbours. Whatever her motives, Maria Gibbs remains one of the most mysterious of BC’s Black pioneers.

Alone, Gibbs carried on with his usual energy, looking after his investments, conducting municipal business and taking an active part in colonial politics. He was a well-liked and respected figure, and a sought-after speaker. But though he prospered in the colony, Gibbs was still in many ways an outsider, frustrated by the “old fogies” and their lack of “Yankee enterprise.”

One outlet for this frustration was a series of letters that he published in The Elevator in the spring and summer of 1868. In the first of these he praised the potential of British Columbia while damning its government: “We have been badly governed. . . . hundreds of agriculturalists seeking land to settle were treated with such nonchalance or charged such fabulous prices that they left.” Gibbs noted the gradual improvement of farming despite lack of government support, and he saw a bright future for mining: “We also have an anthracite mine which will be of great value not only to the owners and to the colony, but to the Pacific coast, it being the only anthracite mine yet discovered on this side of the continent. The company (of which the writer has been a director) has spent $60,000 already . . . with a promise of excellent returns.” The timber market was also improving: “One year ago it was a difficult matter to induce an intelligent shipmaster to load his vessel with lumber or spars at Burrard Inlet; today seven large vessels are loading or preparing to load at the mills there.”

In his next letter, a month later, Gibbs praised English fairness but bitterly attacked the government as “sitting like a nightmare upon the energies of the people, and . . . totally unfitted for an intelligent community in the nineteenth century. . . . The Governor is the personification of official imbecility. . . . We have a legislature . . . which is but a sham.”

More interesting than his description (which many British Columbians would have applied to every government from Douglas to the present) is his remedy: “a cheap and responsible government; to economize, by reducing it numerically, or by increasing its efficiency; to have a responsible government of the people, for the people, and by the people.”

In other words, Gibbs was now weighing the possibility of seeing British Columbia annexed to the United States. In this he was allied with many Victoria businessmen, who for a time actively resisted the idea of confederation with the remote Canadian colonies. Like them, Gibbs was an annexationist on economic grounds, but he took care to praise the idea without committing himself to it personally.

“Annexation was quite popular with the masses,” he wrote in The Elevator, “but not with the colonial elite of government officials and wealthy Englishmen whose support would be necessary for such a step.”

This was not entirely accurate. Such establishment figures as John Helmcken (a political supporter of Gibbs) were very cool to confederation and willing at least to consider annexation. Speaking for himself, Gibbs said, “I have no very decided convictions of the impropriety of territory changing ownership; . . . land should belong to those who by the accident of locality or superior ability can utilize it most efficiently and produce the greatest development.”

But the annexation movement failed to win wide support, and Gibbs saw confederation as the only practical alternative. In his last Elevator letter, written in July, Gibbs described the impending union with Canada as a consequence of “the great principle of national centralization and fraternity,” which was uniting Germany and Italy. He criticized the Assembly for having voted against confederation for “the very human reason that they were not fools enough to vote themselves out of office—thus presenting in a nutshell the rottenness of the present system.” And after praising confederation because it would end autocratic colonial government, Gibbs wrote:

"But to the new nation: Who shall write its rise, decline and fall? Spring into existence almost in a day, with four million of people, a population larger than the United States possessed when they commenced their great career, who shall correctly predict its future?

That the banner of the Dominion and the stars and stripes, linked and inter-lined, may go forward in healthful rivalry to bless mankind and hasten the day when from pole to pole men may exclaim, “The world is my country and all mankind my countrymen!” is the sincere desire of the writer.

"

In the fall Gibbs was elected to represent Saltspring Island at the Yale Convention, where terms for British Columbia’s entry to Canada were defined. The convention was largely the work of Amor De Cosmos, with whom Gibbs was evidently now on better terms. While Gibbs’s contribution to the convention is uncertain, his presence was used by some to deride the cause of confederation. A Victoria baker, Andrew W. Piper, even concocted a sugar sculpture showing a very dark-skinned Gibbs arm in arm with a very drunk De Cosmos.

Such crude gibes could not stop confederation, and racist appeals failed to keep Gibbs from being re-elected to the Victoria City Council in 1868. He was a well-known member of a minority that was now too small to be seen as a threat. The 1868 census showed just 127 Black adults in the Victoria district, whose White population was 2,200.

Though Gibbs was a conscientious and effective councillor, he was soon restless. The Queen Charlotte Coal Company, of which he was both a director and a major shareholder, called for tenders to build a wharf and tramway to serve its new mine; Gibbs resigned his directorship and put in a bid. It was accepted, though it was not the lowest one.

In January 1869 he embarked for Haida Gwaii on the steamship Otter with a crew of fifty: surveyors, carpenters, blacksmiths and labourers. He had a three-month leave of absence from the city council and expected to be home in time for the opening of Victoria House, the largest and most modern mercantile building in the colony, which he had been building on one of his downtown lots.

The Otter’s destination was a rough camp on Graham Island, a few miles up the Skidegate River. The Haida people gave the newcomers a friendly reception. “They were friendly and docile,” Gibbs later recalled,

"lending ready hands to our landing and afterward to the cargo. I was surprised, while standing on the ship, to hear my name called by an Indian in a canoe at the side, couple with encomiums of the native variety, quite flattering. It proved to be one who had been a domestic in my family at Victoria. He gave me kind welcome, not to be ignored, remembering that I was “in the enemy’s country,” so to speak.

"

Gibbs was careful to maintain good relations with the Haida people, on whom he relied for most of his work force. A decade earlier, Governor Douglas had complained about the unreliability of Indigenous workers, but Gibbs’s experience with them was better: “While their work was dispatched without celerity of trained labor, still, as is general with labor, they earned all they got. . . . I found many apt, some stupid; honesty and dishonesty in usual quantities.”

Cultural differences did pose some difficulties. The original samples of coal had been carried down the slopes of Mount Seymour by Haida workers who were paid in tobacco for each bag of coal delivered on the ship. No one had been in a rush then. But now, as work settled into a routine, the Haida workers often went on strike—not for more wages, but for more time.

The workers who had come with Gibbs were of varied nationalities and included three other Black men. For once, racial and national animosities were a benefit: each group disliked the others, but none was large enough to form a bloc that might slow down the work.

Nevertheless, the work did go slowly. The men were hampered by almost constant rain and by the effects of liquor and casual sex with local women. Gibbs found the engineering problems of the tramway more formidable than he had imagined. The mine was a mile and a half away from the shore at Anchor Cove, where he was building a shipping wharf. By July 1869 he had completed only two thousand feet of the railway. It was eventually completed in two sections: the first carried coal about a third of the way down the mountainside, where it was dumped into a chute and fell into cars on the second section, and then carried to the wharf.

His leave of absence from Victoria City Council had long expired, and the councillors reluctantly declared his seat vacant. (It was taken by Arthur Bunster, a cheerful and bigoted Irish brewer whose long political career was based on jokes and rabid anti-Chinese sentiments.)

Some confusion exists about how long Gibbs remained on Graham Island. He himself says he left in 1869. His biographer Tom Dillard says the first shipment of anthracite did not leave until May 5, 1870—sixteen months after Gibbs had first set foot on Graham Island—and that Gibbs himself was aboard. The Colonist ran a complimentary report about his return on May 18, 1870, so evidently Gibbs had forgotten the exact year. Dillard says that Gibbs still made a profit from the Queen Charlotte Coal project despite its delays.

It was also his last achievement in British Columbia. While he kept ownership of Victoria House, he wrapped up his other affairs and departed at once for the US.

“It was not without a measure of regret that I anticipated my departure,” he wrote in his autobiography.

"There I had lived more than a decade; where the geniality of the climate was excelled only by the graciousness of the people; there unreservedly the fraternal grasp of brotherhood; there I had received social and political recognition; there my domestic ties had been intensified by the birth of my children, a warp and woof of consciousness that time cannot obliterate. Then regret modified, as love of home and country asserted itself.

"

This was characteristic of Gibbs: to fight battles and forget them. Privately he may have nursed resentments against his British hosts, but publicly he expressed himself with considerable tact.

Unfortunately, he maintained that tact in discussing his political status: “I had left politically ignoble; I was returning panoplied with the nobility of an American citizen.” But he had become a naturalized British subject in 1861, and it is unclear how his American citizenship was obtained.

In Oberlin Gibbs briefly reunited with his family while he studied law at Tanner’s Commercial College, a private business school. He did not, as some accounts claim, enrol at Oberlin College. (Four of his five children would study there, however.) He had read English common law in Victoria under D. Babington Ring and was graduated from Tanner’s in less than a year. He then left Ohio and his family, planning to settle somewhere in the South. It was no small achievement for a man nearing fifty to embark on a new career in unfamiliar country.

His first stop was Tallahassee, Florida, where his brother Jonathan—a Dartmouth graduate—was Secretary of State. White resistance to Black participation in government was already well organized: to sleep, Jonathan Gibbs had to climb to the attic of his large home and surround himself with a small arsenal against raids by the new Ku Klux Klan. Though encouraged to settle in Florida, Mifflin Gibbs felt that to do so would be taking advantage of his brother’s position. He moved on.

In 1871 Gibbs entered a law firm in Little Rock, Arkansas. A year later he opened his own firm. Once settled, he seems to have been temporarily reunited with his wife, but she eventually returned to Oberlin.

Success in Gibbs’s new profession came swiftly. In 1873 he became the first Black man to be elected a municipal judge—and by a mostly White electorate. He also became an important figure in the state Republican party and was a delegate to most of the Republican presidential conventions for the rest of the century.

After Reconstruction, however, a Black Republican in a Southern state ran some risks. Years later, he told an interviewer in Los Angeles that he had sometimes “stumped the state” when hostilities were so intense that “my wife never expected to see me again, and I saw my fellow-men shot down by hot-headed Democrats, who tried to break up the meetings.” His loyalty was sometimes more than the party deserved: in 1876 he was one of the 306 convention delegates who tried to nominate Ulysses S. Grant for a third term as president.

But as his biographer Tom Dillard noted in a 1976 article about him, Gibbs flourished for forty years in patronage politics. Republican administrations rewarded him with several important posts, including registrar of the US Land Office for Little Rock and receiver-general of public money. He filled these quite ably. But he was looking for new challenges and constantly lobbied his political allies for a position in the foreign service. (Black Republicans in the South were being pushed out of influence by the “Lily White” faction, Jim Crow was establishing itself and Gibbs may have considered it wise to leave the country again.)

In 1897, at the age of seventy-four, Gibbs was appointed US consul for Madagascar. That was about as good a position as a successful Black American could aspire to. Surprised and excited, he accepted the post and embarked on New Year’s Day, 1898; after a month’s stay in Paris, he resumed his journey and arrived in Tamatave—a small coastal town—in mid-February. He was just two months short of his seventy-fifth birthday, and he would be nearly seventy-eight when he left.

For over three years, Gibbs lived in that remote tropical backwater, becoming a popular and respected member of the small foreign community. His assistant, William Hunt, was a foreign service professional who would marry Gibbs’s daughter Ida in 1904.

The climate was brutal; bubonic plague and “Malagash fever” were seasonal hazards. When he returned home in 1901, it was with some eagerness.

His next project was the writing of Shadow and Light, which he published privately in Washington, DC, in 1902. It was less an autobiography than a kind of scrapbook, with some vivid passages and some equally vivid silences—for example, about his marriage. Dillard says it did not sell well, and many copies ended up as wedding and Christmas gifts.

At about this time, his estranged wife, Maria, seems to have died. Oberlin city directories list her as a resident from at least 1873, sometimes sharing her home with her daughters, Ida and “Hattie” (Harriet). But after 1902 her name disappears from the directories.

Despite his distance from his family, his children had for the most part done well. One son, Wendal, had died in 1885 at age twenty. He had been a student at Berea College in Kentucky and was buried in Little Rock. Donald Gibbs, born in Victoria just after the theatre riot of 1861, studied at Oberlin from 1875 to 1879 and then became a mechanic. Dillard says he moved to Tacoma, Washington, in 1901. Horace Gibbs, who graduated from Oberlin in 1882, became a printer and businessman in Illinois.

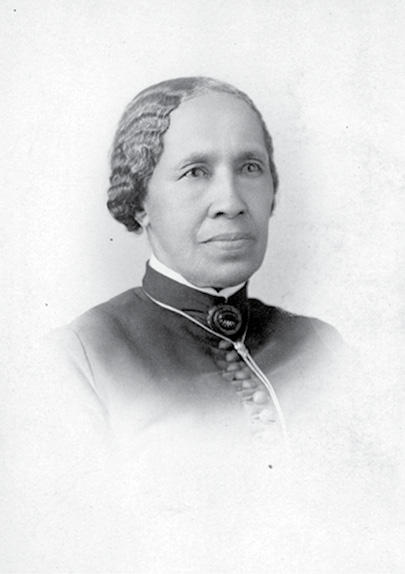

The daughters were to leave the strongest record. Ida, born in 1862, graduated from Oberlin in 1884 and taught in Huntsville, Florida, and Washington, DC. After her marriage to Hunt in 1904, she became a diplomat’s wife, living in Madagascar, France, the Azores and Liberia. She died in 1957.

Harriet, born in 1869, was the youngest of the children. A talented musician, she was the first Black graduate of Oberlin’s school of music in 1889 and later studied in Paris. After a stint as director of music for the Black schools in Washington, DC, she established a music conservatory in Kentucky. With financial help from her father, she established the Washington Conservatory of Music. Harriet also wrote a book on the history of Haiti and married a well-known Black lawyer, Napoleon Marshall.

Back in Little Rock, in 1903 Gibbs became the president of Capital City Savings Bank, most of whose depositors and staff were Black people. The position gave him time for considerable travel, and in 1907 he revisited Victoria. A story in the Colonist described him as a Democrat, and got several other facts wrong, but this was getting off lightly compared to the days of Amor De Cosmos’s race-baiting.

The bank flourished for several years, directed by the Black elite of Arkansas. But as Dillard notes, “no one suspected that the bank was ill-managed.” A run on the bank in 1908 forced it to close. A White attorney became the court-appointed receiver; he found the records “ill-kept and incorrect,” with many overdrawn accounts. Early in 1909, a grand jury indicted Gibbs and the bank directors, and his personal estate, worth some $100,000 was sequestered.

A few months later, Gibbs reached an out-of-court settlement on claims against him of $28,000. Dillard says the grand jury indictments were dismissed, and Gibbs evidently regained control of his personal fortune. But he had lost much of his reputation as one of the country’s most successful Black businessmen.

On July 11, 1915, at the age of ninety-two, Mifflin Wistar Gibbs died. Little Rock’s new Black high school had been named for him. He had also donated the land for a home for aged Black women and had supported the home with sizable donations. “He leaves a large estate,” Little Rock’s Gazette noted in his obituary.

We know little about the other Black pioneers who returned to the US. John Craven Jones, Saltspring’s first schoolteacher, returned to Oberlin in the 1870s. In 1882, at the age of fifty-one, he married Almira Scott, who had graduated from Oberlin in 1870 and the couple moved to Tarboro, North Carolina. There he resumed teaching for another twenty-five years. He died in 1917.

Elias Toussaint Jones left Barkerville in 1892 and returned to Oberlin. In 1895 he informed the Oberlin College alumni office that in 1893, age fifty-nine, he had married; his wife, Blanche, survived his death in May 1917.

His older brother William Allen Jones, an 1857 graduate of Oberlin, also provided the alumni office with news about himself. In 1895 “Painless” Jones was still in Barkerville, working in “Gold Mining and Dentistry.”

The Jones brothers and the Gibbs family must surely have known each other in Oberlin, if not in British Columbia. Would the brothers sometimes have visited Maria Gibbs and her children in her house on College Street? Did they see their sojourn as a mistake, an adventure, a failed experiment? As Reconstruction ended and White supremacy triumphed, did they ever wish they had stayed in the “God-sent land for the colored people”?

The departure of Mifflin Gibbs marked a turning point in the history of the Black population of British Columbia. He had been widely regarded as the leader of a distinct community, with its own interests and the power to pursue them. Now the leader was gone and the community’s nature had radically changed.

Many of the immigrants of 1858 had left long before him. In the early 1860s, perhaps eight hundred to a thousand Black settlers had lived in the British Northwest. The 1871 Victoria directory numbered just 439 Black residents (many of them children) in the whole of the new province of British Columbia, not counting Saltspring Island’s estimated ten Black families.

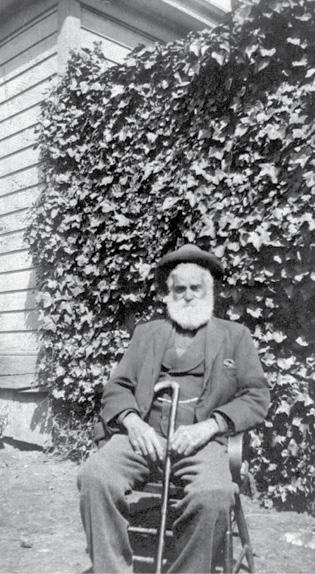

One family that remained behind was Peter Lester’s. His beating in the San Francisco boot shop had helped to launch the Black migration. He seems to have found some comfort as well as success in his new country. The 1875 voters’ list includes him as a resident of Vancouver Street in James Bay, a “gentleman” living with his wife, Nancy, and their son Peter Junior, who was a building painter. His son Frederick Douglass Lester, a carpenter, lived nearby with his wife, Octavia, and their two children, Blanche and Frederick Junior.

Peter Lester left no written record of his life, and we do not even know when or where he died. His wife, Nancy, died at eighty-two in February 1892 and was buried in Ross Bay Cemetery. Their children and grandchildren seem to have left the province.

The White and Chinese populations, meanwhile, had been growing. White dislike of Asian immigrants had always been strong, and it increased throughout the rest of the century. The Black citizens were no longer much noticed; when they were, White people saw them as natural allies.

James Morton, in his history of the Chinese community in British Columbia, quotes a Colonist editorial of 1875 that rebuked a city councillor for saying that the Chinese population should be able to vote, since Black British Columbians already could: “Colored persons differ only from the white in point of colour,” the editorial asserted.

"In language, religion, habits of life, and thought, they are the same. They are not less intelligent, enterprising, industrious, orderly, benevolent. They own as much property, pay as much taxes. In a word, they are no less citizens and no less capable of making good use of the electoral franchise on account of their colour.

But in all these respects the Chinese are essentially different and are likely to remain so . . . they are precisely the element to be desired and used at an election by the designing and unscrupulous.

"

No doubt some Black readers grinned wryly at this accolade, remembering Amor De Cosmos’s use of the same arguments against them during the 1860 election.

In effect, Black British Columbians had suffered a kind of pyrrhic victory. They had lost their influence as the balance of power between the White establishment and reform factions. They had endured insults and discrimination while the government they supported looked the other way. They had seen some of their most enterprising community members return to the United States.

But they had come north in 1858 intending to integrate themselves, not to build yet another ghetto. For those who remained, that integration was now in many ways achieved. The Victoria city directories listed them as living next door to White and Chinese residents. They would still encounter bitter prejudice, but not of the sort they had faced in the early 1860s. They sat where they chose in the theatres, voted as they pleased in the elections and got on with their lives as individuals. Too few to be seen as a political or economic threat to the White majority, they had become—as Adam Rudder says in his 2004 MA thesis on the history of Vancouver’s Hogan’s Alley—invisible.

Invisible or not, they continued to make contributions to British Columbia in its first decades as a Canadian province.

One man who did much to open up the far northwest of the province was a Black prospector named Henry McDame. According to an anonymous article in Canada West Magazine, McDame was a native of the Bahamas who came to BC in 1858 and spent an uneventful decade prospecting in the Cariboo.

Then, in 1870, he was one of four men who discovered a rich gold creek in the Omineca. Four years later he pushed on into the Cassiar wilderness; ninety miles from Dease Lake he found gold again. To exploit the claim, McDame and several other miners—most of them Black—formed the Charity Company, which took out six thousand dollars’ worth of gold in its first month of operations. The stream on which the Discovery claim was located was named for McDame.

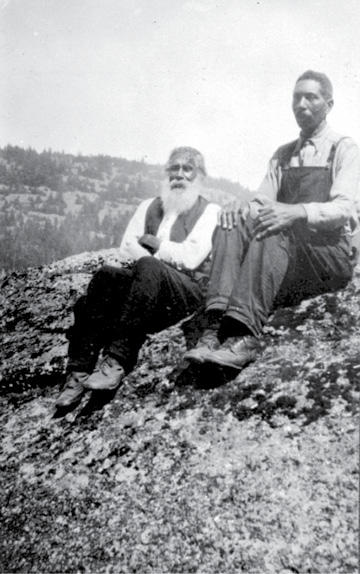

He may have been better at finding gold than at keeping it. A decade later, in 1884, he was exploring the Skeena district with a grubstake from Samuel Booth, a prosperous Black Victorian. Here he found several gold-bearing streams, most notably Lorne Creek. What became of him afterward is uncertain; a photograph of “old-timers” taken in Telegraph Creek in 1897 includes a Black man who may have been Henry McDame.

One of McDame’s Black mining partners, John Robert Giscome, also left his name on the BC landscape. A Jamaican born in 1832, he had come north with the pioneers of 1858. Giscome Portage, north of Prince George, was a nine-mile shortcut between the Fraser River and Summit Lake, established when Giscome and McDame were venturing toward the Omineca. The Huble Homestead Historic Site, at the south end of the portage, is the start of the Giscome Portage Trail. Giscome Rapids and Giscome Canyon, both near the portage, are also named for him.

Giscome appears to have retired fairly well off; he died in Victoria in 1907, aged seventy-five, and was buried in Ross Bay Cemetery.

Another of McDame’s partners in the Omineca was Daniel Williams, very likely the same Daniel Williams who became a legend in the Peace River Country. Born in Ontario, Williams came West in 1857 as a cook with the Palliser Expedition, which explored the Prairies. He decided to stay in the West and became a successful trapper and prospector.

In 1869 Williams became the first independent settler at Fort St. John, a Hudson’s Bay post. His quarrels with the HBC lasted for years: he disliked chasing the traders’ livestock out of his vegetable garden and was outraged when the company claimed his farm as part of its property. Williams was also the first person to grow wheat in the Peace River Country, a region then considered hopeless for agriculture; he proved the opposite.

Thanks to his prickly personality, Williams gained a reputation as a dangerous man, one who had even got away with murder. On one occasion at Fort St. John he shot at a man named McKinley and was tried on a charge of “causing a disturbance.” A miner named Banjo Mike conducted Williams’s defence. James G. MacGregor, in his book The Land of Twelve Foot Davis, tells the story well:

"Banjo Mike was able to prove that Dan was only a short distance from McKinley when he fired at him. Having established this point, Mike turned triumphantly to the jury and said: “Gentlemen, let me tell you this: I know, as many other miners know, that Dan Williams at a distance of one hundred yards can take the eye out of a jackrabbit at every pop. Well, gentlemen, had Dan Williams had the slightest intention of harming Mr. McKinley, Mr. McKinley would not be here to tell you this amusing little story, whereby he gives you credit for some sense of humor without paying you much of a compliment for intelligence.”

"

According to MacGregor, Williams’s sentence was greatly reduced thanks to this argument.

Williams returned to the Peace River after his release from jail. Some sources believe he was the Black man named Williams who was hanged for murder in Calgary in 1884, but it seems more likely that he died in 1887 while wintering on the Finlay River—perhaps of illness, perhaps murdered by his partner.

Most of the province’s Black settlers continued to live in and around Victoria, pursuing careers somewhat less spectacular than that of Daniel Williams. Thomas Whiting Pierre was a successful tailor; he and his wife, Ann Elizabeth, raised six children (all baptized in 1874). Ann died in 1899 at sixty-seven, and Thomas in 1904 at seventy-two. Many of their children would marry those of other Black pioneers.

Richard Stokes, born in the 1830s, ran his own livery stable for a time, and in the 1881 Victoria census he was listed as a stableman living with a White family. He died in 1885.

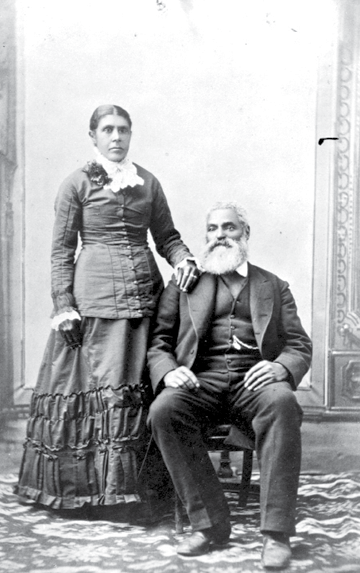

James Barnswell, a Jamaican, became a prominent member of the community during the 1870s and the patriarch of a large family. Born in 1829, he arrived in Victoria during the gold rush years and established himself as a carpenter, building some of the city’s most elegant homes. In 1871 he married Mary Lowe, who had been born in Puerto Rico and who had arrived in BC as an orphaned teenager speaking only Spanish. Provincial records list her as Mary Louisa Barnswell, probably born in 1854, baptized in November 1876 and dying in 1947 at the age of ninety-three. James Barnswell died in 1919 at the age of ninety. The Barnswells had ten children, some of whose descendants still live in the province.

Robert Clanton, an Ohio-born baker, was another well-known figure. In 1866 he married Victoria Richard—a daughter of Fortune Richard—and founded a family from which many modern BC Black families are descended. The 1881 Victoria census lists them as living on Johnson Street with three children: Clara, thirteen, Robert, eleven and Frederick, seven. Ten years later Robert Senior was a store clerk and the family was still living as a household, now on Yates Street.

If Daniel Williams was the archetypal Peace River backwoodsman, Charles Alexander was the frontier patriarch. Born in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1824, Alexander was the son of a Black mother and an Indigenous father. Like his wife, Nancy, he was born free. After their wedding in 1849, they lived in St. Louis until 1857, when they moved to California. Arriving at the peak of anti-Black feeling, the Alexanders soon left for Victoria as part of the emigration of 1858.

While his wife stayed in Victoria, Charles Alexander went to the goldfields of the Fraser, where he did well as a miner. In 1861 he rejoined his family and bought land at Shady Creek, in the Saanich district north of Victoria. He soon became a prominent and respected farmer.

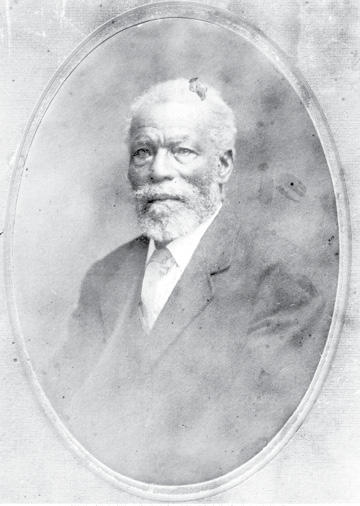

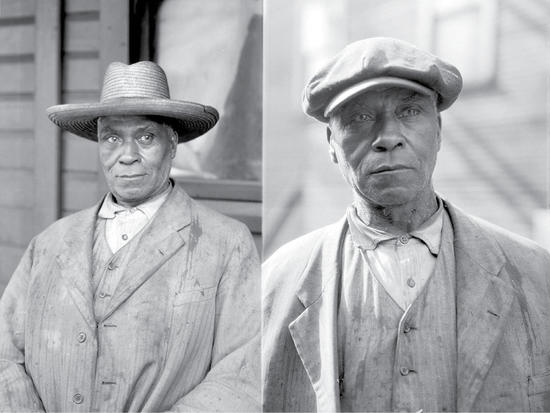

Alexander helped to build Shady Creek Methodist Church in the early 1860s, on land owned by a Black man named McMillan. For some years the church had no regular minister, but Alexander himself often preached there. George Glover, in his history of the United Church in the Saanich area, gives us a description of Charles Alexander that matches his photograph:

"He stood six feet two inches and weighed over 200 pounds, with broad shoulders and a deep, splendid voice for both singing and speaking. His great broad hand gripped in a most friendly greeting and that grip was never forgotten. In his way he was a Bible scholar and a most interesting and capable teacher and preacher. He was one of a group most anxious to have a church in the community and gave much of his time and ability as a carpenter to help in this purpose.

"

Alexander also served as a school trustee, helped to build the first schoolhouse in South Saanich and was a founding member of the local agricultural and temperance societies. After retiring from farming, he and his wife moved to Lake Hill; it was there that most of their large family gathered on Christmas Day 1899 to celebrate the Alexanders’ golden anniversary. The Colonist reported the event at some length:

"Golden Wedding—Unusual celebration held at Lake Hill—On Christmas Day, Mr. and Mrs. Charles Alexander of Lake Hill, formerly of Saanich, were married in 1849 in Springfield, Illinois. Twelve children were born to them, of whom seven are still living, and besides they have 21 grandchildren. With the exception of one daughter, all were present at the celebration.

"

Some of the oldest families in the province were also there: the Dallas Helmckens, the Tolmies, the Howards and the Shakespeares. Among the Black guests were Robert and Victoria Clanton, Mrs. Julia Spotts, Mrs. Elizabeth Pierre and James and Mary Barnswell—all of whom had come to Vancouver Island in the gold rush years forty years before.

Charles Alexander died in 1913 at the age of eighty-nine and was buried in the Shady Creek cemetery beside his wife, who had died two years earlier. In the early 1900s the Alexander family ran a successful coal business in Victoria. One Victorian recalled that the men in the business could all carry sacks of coal weighing over two hundred pounds.

Many of the family were buried in Ross Bay Cemetery, including Corinthia Pierre Alexander and Frederick Barnswell Alexander—names reflecting the growing relationships among the Black pioneer families.

Many of the Alexanders’ descendants still live in British Columbia, where they are active in business, the professions and education. One of them, Norman Alexander, was a long-time instructor in forest resources at the BC Institute of Technology and a president of the BC Association for the Advancement of Coloured People.

The Spotts family, who were represented at the Alexanders’ celebration, had been well known in BC for years. Fielding Spotts arrived from California in 1859 (the 1881 Victoria census says 1852), and in 1860 brought his wife, Julia, and their infant son, Fielding William, to join him. The family farmed on Saltspring for a few years before moving to Saanich.

Spotts, like Alexander, served for many years as a school trustee. He and Julia, along with Thomas W. Pierre, helped found a Baptist church in Victoria in 1875. The church went through repeated financial crises and reorganizations, with Spotts always ready to rebuild. Reorganizing in 1883, the twenty-three members included in their covenant, “No distinction shall ever be made in respect of race, colour, or class.” When Spotts died in 1902, the church’s annual report included an obituary, describing him as “a simple trusting consistent child of God, respected by all who knew him.”

The family’s eight children were well liked, and several were renowned local athletes. Fielding William moved to Vancouver in 1902; he died there in 1937, aged seventy-nine and one of the last of the original pioneers.

One veteran of Victoria’s all-Black police force, Loren Lewis, made a career of law enforcement. According to William Daniel Anderson, a Black man who was born in 1856 and grew up on Saltspring Island, Lewis served for years as a district constable on the Songhees Indian Reserve outside Victoria. He later became a member of the BC Provincial Police, as did Anderson himself. Lewis evidently did some farming as well, and was on the South Saanich voters’ list until 1877. He appears in the 1881 Victoria census, sixty years old and the head of a household consisting of himself and three sons: Samuel, Sherman and Loren D.

John Sullivan Deas, salmon entrepreneur

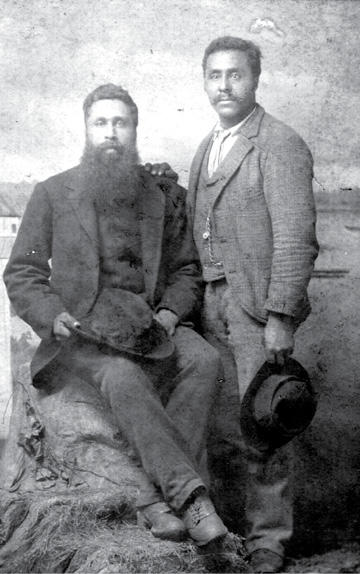

A Black businessman named John Sullivan Deas gained some prominence on the Lower Mainland during the 1870s. Thanks to the research of H. Keith Ralston, a UBC historian, we now know about Deas’s career in some detail. Deas was born in South Carolina in 1838 and became a tinsmith while still in his teens. By 1860 he was working in San Francisco, and in 1862 he moved to Vancouver Island, where he married Fanny Harris that same year. The wedding took place in the home of Richard H. Johnson, an officer in the African Rifles and later the builder of the Mount Ararat Hotel in the Sooke gold rush.

The couple moved to Yale, where their first son, Robert Lyles, was born in 1866. Another son and two daughters were born and baptized by 1872.

By 1868 Deas had moved back to Victoria, where he set up Birmingham House, a hardware and stove business. In 1871 he and his family moved into Richard Johnson’s house, Johnson having recently died. The new tenants were the victims of a prank: another Black man, carrying a “bull’s-eye” lantern, came up to one of the windows on the family’s first night in the house and so frightened them that they moved out the next morning. The “haunting” caused a brief sensation in Victoria until the truth came out a few days later.

In that same year, Deas contracted with Captain Edward Stamp to make the cans for Stamp’s new salmon cannery venture in New Westminster—one of the first in British Columbia. Stamp died soon after, while trying to raise more capital, but with backing from a Victoria merchant, Deas was able to go on canning.

In 1873 he pre-empted the island in the Fraser Delta that now bears his name; on it he built a sizable complex of buildings that served as cannery, warehouse and bunkhouse. Here he began packing salmon in cans lithographed for him by Grafton Tyler Brown, a Black artist in San Francisco.

For several years Deas contended with uncertain salmon runs and technological problems. Still, in the early 1870s he was arguably the most successful canner on the Fraser. Aware that the river could not sustain operations on the scale of the Columbia River canneries, Deas watched his increasing competition with some foreboding. In 1877 the owners of a rival cannery charged him with using “violent and threatening” language to their fishermen. The case was thrown out of court, but not before Deas had been put to the inconvenience of appealing a three-week jail sentence. The Mainland Guardian observed that the whole matter was obviously intended to interfere with Deas’s operations at the height of the canning season.

Such tactics helped to end Deas’s career in the new industry. His output fell from first to third place in 1877, and as still more canneries were being set up for the 1878 season, he saw little point in remaining. Late in 1877, his wife, Fanny, bought a rooming house in Portland, Oregon. After working through the peak of the 1878 season, Deas sold out to his Victoria backers for fifteen thousand dollars; after clearing up his affairs, he joined his family in Portland. Two years later he died at the age of forty-two. As Ralston observes, tinsmithing was a notoriously unhealthful trade, and Deas’s early death may have been related to his work.

The pioneers in old age

Those Black pioneers who remained in British Columbia continued to experience mixed fortunes in their adopted province. John Sullivan Deas—a pioneer in one of the province’s major industries—is today known only because a major highway goes under the Fraser through what for years was named the Deas Island Tunnel.

Willis Bond, the popular orator and businessman, went on enjoying controversy. In 1886 he attended an anti-Chinese rally in Victoria at which only he and Victoria’s mayor, James Fell, spoke against a resolution calling for deportation of all Chinese residents in the province. The audience shouted him down, but one suspects that Bond was delighted to see he could still stir up his opponents. He died in Victoria in 1892 at the age of sixty-eight. His wife, Martha, lived on into the twentieth century, dying in 1903 at seventy-three.

Wellington Moses settled permanently in Barkerville, a well-known and beloved old-timer despite his fine for sexual assault. He seems to have had no children of his own, but the children of Barkerville often got presents from him at Christmas: toy trumpets, slates, tea sets and dolls. In his diary in 1875, he mentioned the burial of six-year-old John Kelly in nearby Cameronton. Though he did not express his feelings about it, no doubt he shared the parents’ sorrow. He died in 1890 at seventy-four.

Fortune Richard, one of the original Pioneer Committee, took little part in public life after the disbanding of the African Rifles. In the 1881 Victoria census, he and his wife, Clarissa, are listed—mysteriously, as both single—and at the age of seventy-four he still called himself a shipwright. Both he and his wife had been born in Florida in the first decade of the nineteenth century. They had come north from San Francisco not as an adventurous young couple, but in their middle age, and had built a new life for themselves. Sherry Flett, who has researched many of the Black pioneers, believes that Fortune had moved to Victoria two years before Clarissa did. In 1882, Flett says, Fortune Richard published a protest against the local Baptist church, which had attempted to exclude Black congregants. Perhaps this was the event that caused the revived church, in 1883, to explicitly ban racial discrimination among members.

Clarissa Richard in 1885 signed a petition to grant women the right to vote. She died five years later at age eighty and was buried in Ross Bay Cemetery. Mysteriously, no record survives of Fortune Richard’s death or burial. He must have died at a great age in the late 1880s or 1890s, but perhaps not in British Columbia.

The few records we have of Clarissa’s younger sister reflect the uncertainty of nineteenth-century records. According to the Victoria census of 1881, Clarissa Richard’s sister Sophia Page was then living next door to the Clantons—and at the age of sixty-nine, Sophia was looking after three very small Black children also named Page. Were they grandchildren? They do not appear in later censuses.

Then, in 1892, Sophia at the age of seventy-nine married a White Englishman named George Everton, who was sixteen years younger. He first appears in the BC records as a “minister of religion,” called west to be the pastor of Victoria’s Baptist church in 1880. He seems not to have stayed long in that post, but he remained in Victoria as a merchant in the 1891 census and as a “dry goods pedlar” in 1901, when he was seventy-two. His English wife, Mary, nine years older than he, evidently died sometime in the 1880s.

Sophia died in Victoria in 1903 at ninety. Her White husband died in 1907 at seventy-eight. It would be a great insight into the society and culture of British Columbia in the early twentieth century if we could learn more about this unusual marriage.

In 1872 the Stark family moved from Saltspring Island to a new home in Nanaimo’s Cranberry district. Louis Stark’s daughter Marie recalled the day:

"I was too young to remember my age, but I remember well the day we left Saltspring. I carried the memory of that scenic path leading uphill through blue grass to a fence with bars to pull down and pass through. . . . It was sometime in the early seventies, when we embarked on the SS Maud, a mere tug boat but strong and seaworthy, carrying many a head of livestock as well as passengers. The steward on the boat was a coloured man, Scott was his name, we have his photograph yet, none the worse for age. . . .

There was no snow when we left the island, when we came to Nanaimo a thin layer of snow had fallen.

"

The family’s new farm was called the Extension. The 1881 census lists Louis and Sylvia and four children in the household: Abraham, eighteen; Hannah, fifteen; Marie, thirteen; and Louise, two.

Willis, the eldest son, had remained on Saltspring to look after their farm; otherwise they would have lost their pre-emption. John, born in 1860 soon after the family’s arrival on the island, may have already begun his career as a prospector. The Starks’ eldest daughter, Emma, became a schoolteacher while still in her teens and taught on Vancouver Island in the 1870s. She married a man named James Clark in 1878 and died in 1890 at thirty-three, reportedly of tuberculosis.

At some point Sylvia returned to Saltspring while Louis remained on his new property. Soon after, a rich coal seam was found to run through his land, and he received urgent offers to buy his farm. Stark turned them down.

Then in 1895 he was found dead at the bottom of a cliff. Though murder could not be proven, the family was sure that he had been killed. According to one account, Louis’s son John—a noted prospector who was the co-discoverer of the Dolly Varden mine in the Yukon—tried to investigate his death. But he himself was threatened and even shot at, and several witnesses died before they could testify.

Louis’s will expressed considerable bitterness toward the woman who had followed him up the trail from that dangerous beach on Saltspring over thirty years before: he left her exactly “1 dollar in lieu of dower because she has some years since without cause left my bed and board consequently she is not entitled to any of my property.” Instead he left it to his youngest daughter, Louise. In the 1891 census of Vancouver Island, she is listed as twelve years old, living with her seventy-five-year-old father. In the 1901 census, she is a lodger in a White Nanaimo household, reportedly unable to read or write. Also in 1901, aged twenty-two, she married Ernest May, a butcher, in Vancouver. She died in 1971.

We know a little about Abraham and Hannah. Abraham is on the 1898 provincial voters’ list, a farmer like his brother Willis. But except for Willis we have few records of the Stark sons. In the 1901 census, all three sons are living with their mother on Saltspring.

Marie Stark Wallace describes Abraham as her “invalid brother,” born in 1863 after Sylvia barely survived “a perilous trip” from Victoria in a rowboat that nearly capsized in a storm. Louis had to leave her exhausted on the beach while he took the children home and then returned to carry her home in a chair. In the 1901 census, Abraham is listed as being literate but “of unsound mind.” He died in 1900, aged thirty-seven, probably not long after the census was taken.

Hannah married in 1886 at twenty-one. Her husband was Vincent Janoni, a twenty-eight-year-old Nanaimo watchmaker born in Italy.

Back on Saltspring, Sylvia lived with Willis. As a toddler he had been kept indoors for fear of cougars. As a man, he was a famous hunter of them. He died in 1943 at the age of 86. Sylvia Stark died the next year at 106, her memory still sharp and her storytelling as vivid as ever.

A relative latecomer to British Columbia was Grafton Tyler Brown, a self-taught artist, cartographer and lithographer. According to a 2015 post on the website of the BC Black History Awareness Society, he was born in Pennsylvania in 1841 to a free Black couple. As a teenager, Brown worked for a printer in Philadelphia and then headed west to California on his own. There he worked for another printer, helping to create panoramic views of gold rush towns and the homes of their prominent citizens. Brown also designed the labels for John Sullivan Deas’s canned salmon.

Brown eventually bought the printing business, but in the early 1880s he moved to British Columbia, worked with a geological survey party through the Interior and then settled in Victoria. He set up a studio and produced a number of paintings of the region, as well as other regions of BC. But his stay was brief: in 1886 Brown moved to Portland, Oregon, then to Helena, Montana, and eventually to St. Paul, Minnesota, where he worked for the US Army Corps of Engineers as a draftsman.

A few other Black settlers continued to drift into the province. One of these was John Freemont Smith. Born in the Danish West Indies (now the Virgin Islands) in 1850, Smith was a restless, multi-talented man whose career was much like that of Mifflin Gibbs. He spent some years in Victoria, where he married fifteen-year-old Mary Anastasia Miller in 1877. The 1881 Victoria census lists him as a boot- and shoemaker, living with his wife and three-year-old daughter, Gertrude Florella. Mary had been born in Victoria but her “origin” is given as Northwest Territories—which in those days included today’s Prairie provinces. So she may have been Indigenous or Metis.

The family moved to Kamloops in 1884; Smith started a shoemaker’s shop. In 1886 he moved to nearby Louis Creek, and later liked to boast wryly that he was “the first white man on the North Thompson.” He served as an Indian agent and postmaster in Louis Creek, but also prospected all over the BC Interior. He tried unsuccessfully to develop some mica deposits near Tete Jaune Cache and was also involved in a coal-mining venture at Chu Chua.

In 1898 Smith and his family (now numbering seven children) returned to Kamloops, where he set up a store and also worked as a mining and agriculture journalist. In 1902 he became secretary of the local board of trade; a year later he was elected alderman, a post he held for four years. In 1908 he was appointed city assessor. He had also helped found the local Conservative Association. Smith’s careers as prospector, businessman and Indian agent seem to have been notably untouched by prejudice. He was a popular community leader, respected for his energetic “boosting” of Kamloops.

But in 1912, at least, Smith felt the sting of White prejudice in full.

In his book Battle Grounds: The Canadian Military and Aboriginal Lands, P. Whitney Lackenbauer describes an incident in which John Freemont Smith’s expertise in Indigenous relations was called upon and then cast aside. The Department of Militia and Defence was interested in obtaining fifty acres on the Shulus reserve of the Shuswap Nation for a rifle range. To see if the Shuswap would be willing to grant permission, the inspector of Indian agencies asked Smith to meet with them. He was an ideal negotiator: he had taught shoemaking at the Kamloops Residential School, he had served as an agent for years at Louis Creek and he was Catholic, as were the people he was dealing with.

Smith got quick results. The Shuswap Nation on the reserve wouldn’t sell or lease their land, but they would give the military access to the land “for as long as they wish.” The only requirements imposed on the military would be that no liquor would be brought onto the reserve, and that the Shuswap could pasture their livestock on the rifle range when it wasn’t in use.

This was a welcome outcome, but militia lieutenant colonel Charles Flick, who wanted the land for training his unit, the British Columbia Horse, objected when Smith wrote to him in late December.

“I, as a Justice of the Peace for the Province,” he wrote, “a Canadian militia officer and a good Conservative, have consistently refused to recognise this appointment of a [Black man] to an Indian Agency.” When the Indian Agency responded that Smith was just another agent, Flick went further: “The Canadian Militia is a military organization of whitemen who represent the Anglo-Saxon race, and men of colour have nothing to do with our deliberations. . . . His colour, race and . . . his negro-Siwash family are notorious. We, in the west, have an idea that races subject to the whiteman are better when governed by a whiteman.” Lackenbauer says Flick demanded that henceforth a White man be sent to deal with him.

To its credit, Ottawa told Colonel Flick to give Smith the consideration that any other official should expect. But Flick’s opposition effectively killed an agreement that could have been accomplished very easily. Nonetheless, Smith was appointed Indian agent for the Kamloops District in 1912 and served in the position until 1923.

Robert Dunsmuir’s Nanaimo coal mines were notorious for their grim working conditions and the low wages he paid his miners. But they also supported a community of Black employees. Dunsmuir evidently recruited them from the US; according to Christine Meutzner, manager of the Nanaimo Community Archives, Dunsmuir thought they would be more “docile” workers. Docile or not, about seventy of them settled in Wellington, now a neighbourhood of Nanaimo but then a separate town.

Among them were William Edgar Claxton, a miner from Virginia, and his wife, Emma Richards from Illinois. They were very much a mixed-race couple: BC journalist and baseball expert Tom Hawthorn says William had Black and Native American ancestry while Emma’s was Irish and English. Soon after their son Jimmy was born in 1892, the Claxtons returned to the US. There, Jimmy became a teenage baseball sensation, striking out eighteen players in one game. In 1916 he was taken on by the Oakland Oaks as a Native American (who were accepted in White baseball, while Black players were not). That made him the first Black man to play in White baseball, and he was fired within a week when his background became known to the club. Not until Jackie Robinson, almost thirty years later, would another Black man play for a White team.

Nonetheless, Claxton went on playing for Black teams as a formidable pitcher; he pitched his last game at age sixty-three, on an old-timers’ team.

By then, the Wellington Black community had long since vanished. Most of its members had been single men who, like the Claxtons, preferred to take their chances in the US rather than in Dunsmuir’s mines.

In one of his letters, Mifflin Gibbs had commented on the growing industry on Burrard Inlet; by the mid-1870s, Black pioneers were taking part in that growth. Philip Sullivan, a steward at Moody’s Mill, and his wife, Josephine, were perhaps the first Black residents of what was to become North Vancouver.

His son, Arthur Willis Sullivan, baptized in New Westminster in 1861, was one of the first merchants in “Granville”—better known as Gastown and later as Vancouver. Described in a 1929 Province article as “a coloured man of pale complexion and delicate features,” Sullivan ran a grocery store on Water Street at least as early as 1876. He was also a musician and played the organ at services in the Methodist Hall across the street. Vancouver historian Chuck Davis says that at a harvest festival in October 1880 at Hastings Mill School, Sullivan played the harmonium.

In 1887 he married Annie Elizabeth Thomson, a woman of his own age. She was an active leader of the small Methodist congregation. Their business was destroyed in the great fire of 1886 but was soon re-established in a new building known as the Sullivan Block. Perhaps it did so well that he was able to retire: the 1898 voters’ list gives his occupation as “gentleman” and his address as 231 Oppenheimer Street (today’s Cordova). In 1909 Annie died at forty-eight; her husband survived her until 1921.

Beyond BC, the Yukon

Though most of the Black pioneers settled in southern BC, for a very few the province was just a stepping stone to the Yukon. To reach the Klondike goldfields in the late nineteenth century demanded the same ambition, courage and toughness of their predecessors in 1858.

The Atlin Pioneer Cemetery, not far south of the Yukon border, lies just out of town on the Surprise Lake Road. One of the grave markers, a 1970s replacement for the original, was for “John Ellwood Simons, African, February 8, 1914 age 51 yrs; froze to death.”

The manner of his death was not unusual. Others in the graveyard had drowned, or been found dead on a trail, or accidentally shot (one gunshot victim had been mistaken for a bear). Northern BC and the Yukon, a century ago, were hard places to live and easy places to die.

Simons’s background and his experience in the Atlin gold rush are unknown. We can only speculate that he was one of a number of Black Americans and Canadians who moved north in search of gold in the early 1900s.

But the MacBride Museum in Whitehorse records a number of Black pioneers who moved north from Atlin into the Yukon. Notable among them is Lucille Hunter, photographed in her blind old age before she died in 1973.

Lucille Hunter had been the matriarch of a lively and enterprising community. In 1897 she and her husband, Charles, had travelled from Michigan to the West Coast and then taken the Stikine trail to the Klondike—considered one of the hardest routes. She was heavily pregnant at the time. According to her grave marker and other sources, she was just nineteen.

The Hunters stopped at Teslin Lake to deliver her baby daughter, whom they named Teslin. According to Yukon historian Les McLaughlin, who knew Lucille in her old age, the local Indigenous people had never seen a Black person before: “Not quite sure what to call the Hunters, they simply described them as ‘just another kind of white person.’”

The Hunters moved on by dog team to Dawson City, arriving in February 1898. They staked three claims at Bonanza Creek and went to work. Lucille helped Charles dig for gold while also caring for Teslin. In 1901, according to the Yukon archives, they were among ninety-nine Black people living in Yukon, among almost thirty thousand White residents.

A few years later, McLaughlin says, the family moved to Mayo and staked some silver claims. For years, Lucille, who couldn’t drive, would walk between Bonanza Creek, outside Dawson, to Mayo—about 220 kilometres each way—to work her claims and thereby hold on to them.

Evidently the Hunters did well enough to stay in the Yukon, but their daughter, Teslin, after marrying a man named Jorgensen and having a baby son, died. Then Charles died in 1939, age seventy. Lucille, now sixty, had to care for herself and her grandson, Buster.

She and Buster continued as miners until 1942, when US construction battalions (largely composed of Black enlisted men) began to build the Alaska Highway. Lucille and Buster moved to Whitehorse. According to her obituary, she started a laundry business in a tent, with Buster making deliveries around town. At some point Buster Jorgensen married and moved to Haida Gwaii. Lucille remained in Whitehorse, living on her own despite her failing eyesight.

McLaughlin recalls going past her tiny house, where the old blind lady listened constantly to her radio. The house burned down one night, but she survived and moved into a basement suite. There she remained until she broke her hip a few years later. After that she lived in hospital until her death in 1972. Her grave marker said she was ninety-three.

No doubt Lucille and Charles had known most of the other Black miners in the gold rush era, miners like John Woolfork (who filed several gold claims between 1897 and 1907) and others who worked as labourers, waiters and cooks. One of the most famous Black Dawson City residents was Dora Bennett, better known as Snake Hips Lulu, a dance hall girl, recorded in the 1901 census as a single woman of twenty-eight. (She was gone by the 1911 census.)

The Hunters surely knew the Agees, a family from Ontario. Alonzo Agee and his sons Roy and Harry arrived via the Chilkoot Pass on October 9, 1899, and were duly checked through by the North West Mounted Police.

Alonzo worked for a time as a deckhand on the steamers going up and down the Yukon River. Then he settled down in Dawson City as a barber. Roy and Harry joined him there, as well as the rest of the family, including his wife Martha, another son, Sam, and daughter Helen.

Harry and Roy worked as barbers with their father, but in 1901 Roy, the oldest son, died of peritonitis. The family carried on. Sam gained fame as a member of Dawson City’s 1910 championship hockey team.

What became of the family is unclear. The 1911 Canada census shows “Mattie” Agee and a fifteen-year-old Alonzo (Junior?) living in Dawson City, but none of the others. BC vital statistics record the marriage of Helen Agee, thirty (then a resident of Colorado), with Walter Broyls, thirty-two, in Vancouver on May 17, 1920. Broyls, too, was a barber.

The Yukon Archives offer tantalizing photographic glimpses of a few other Black residents: one was a waiter at a July 4 banquet hosted by the US consul, and others worked as cooks for mining operations.

A photograph survives of Lillian Mabel Taylor, who lived in the Yukon from 1902 to 1913. We are told she worked as a cook and laundress, but also owned mining claims. An attractive woman with a Mona Lisa smile, she is holding a White infant in the photograph. Thanks to census data, we know that she was born in 1889 in Comber, Ontario, returned to Ontario, married twice and died in Chatham in 1947.

According to an article by Katharine Sandiford in Up Here magazine, published in January 2009, Black people have been in the Yukon since 1848, when Perro LeNoire worked for the Hudson’s Bay Company as a hunter and labourer. Sandiford learned a great deal about the Black pioneers, the Alaska Highway builders and those who still live in the Yukon.

She also learned that today’s Black Yukoners are searching for their history. The Yukon Archives’ Hidden History website, sketchy as it is, tells them something. But much remains to be learned by patient, systematic exploration of the countless documents of gold rush Canada.

The experience of the Yukon’s Black pioneers might be dismissed as a mere curiosity—the lives of a small fraction of a small population. Only 99 Black people lived in the Yukon in 1901; the 2006 census recorded 125. But they challenge old stereotypes about who should be living where.

The Yukon’s Black pioneers had to be ambitious, enterprising and strong just to get there. Accustomed to living in a hostile culture, they were ready to take a chance on a hostile environment. Sometimes the gamble paid off. Sometimes, like John Ellwood Simons in Atlin, they paid with their lives.

Joe Fortes, the guardian of Vancouver’s children

A Barbadian named Seraphim Fortes arrived in Vancouver in 1885, aged about twenty. After working for several years as a porter and bartender, he established himself in a little shack on English Bay, just south of Stanley Park. There he became a legend.

According to Vancouver journalist Alan Morley in his book Vancouver: From Milltown to Metropolis, “Joe” Fortes became the virtual proprietor of the beach:

"Scarcely a tyke who was raised in Vancouver in the ’90s or 1900’s but learned to swim with Joe’s hamlike fist gripping the back of his or her cotton bathing suit. . . . how many lives he saved over the years will never be known, but he has been credited with over one hundred witnessed rescues, some of them in desperate circumstances. When—as was bound occasionally to happen—his utmost efforts failed, his grief was shattering to behold. Mothers confidently shooed their children away to the bay for the long summer days with the simple command “. . . and don’t go away from where Joe is.”

"

Those children learned that Joe Fortes was a skilled teacher but also a stern custodian of the beach. William C. Heilbron, a lifelong Vancouver resident, recalled in 1961 a 1900 episode in which he and seven or eight other boys “hijacked” a steam launch and set out on a cruise of English Bay. Joe overtook them in a rowboat.

"Each of the crew, according to rank, got spanked, and hard, by Joe in the places it hurt the worst, and he didn’t mention a word of our delinquency to our parents. . . . He wasn’t hard boiled in the least, he just understood kids.

"

Originally a squatter who lived by odd jobs while acting as an informal swimming teacher and lifeguard, Fortes was eventually appointed officially; he was also made a special constable. In 1910 the city gave him a gold watch and a cheque in recognition of his service.

Morley describes the last days of Joe Fortes:

"In January 1922, Joe became ill. At mid-month he was carried to Vancouver General Hospital with a severe case of pneumonia, halting his stretcher on the way to give minute instruction to the constable on the beat for the care of “his” bay. To all the city, the news came as a shock, for he had become a permanent and indestructible institution. The hospital telephones rang constantly, and his room was knee deep in flowers every day.

"

Joe Fortes’s funeral was the most heavily attended in the city’s history. Holy Rosary Cathedral was packed, with thousands standing outside. A few years later his cottage burned down, but a more permanent memorial still stands: a fountain monument in Alexandra Park with a bronze plaque inscribed: “Little children loved him.” In addition, the Joe Fortes branch of the Vancouver Public Library has served his old neighbourhood since 1976. And the Joe Fortes Seafood and Chop House, on Thurlow near Robson, has offered very good food since 1985.

Despite the fame of a few individuals like Joe Fortes, Black people by the turn of the century were so thinly scattered across the province that they rarely came to public notice. In 1899, a man named Archibald Johnson protested the refusal of some Victoria barbers to cut Black men’s hair. Except for the Alexanders’ golden anniversary, it was almost the only news item about Black residents to appear that year. In the 1901 Victoria census, the total population of the district was 23,688. Just seventy of them were described as “Negro.”

The children and grandchildren of the pioneers acquired a certain reserve in their relations with White neighbours. Nan E. Tremayne, who attended Victoria High School from 1903 to 1906, recalls the mixture of friendliness and distance between her family and a branch of the Alexanders:

"One of my classmates was a Black girl named Wealtha Alexander, who was well-liked by everyone, though never one of any particular group. Her mother was an excellent dressmaker and made dresses for a lot of well-known women, and of course her daughter was always well turned out. Her father was the owner-driver of a dray for whom my father, in the Customs service, had a lot of respect . . . but he was always kept at a respectful distance, and I think I would not have been allowed to bring the daughter into our home. Nor would she have wanted to come.

"

If this was a typical attitude, it indicates that the Black British Columbians had—after almost half a century’s contribution to the colony and province—gained little more than tolerance. They faced far less institutional discrimination than most Black Americans, but that was because they were so few, not because their fellow citizens were enlightened.

In any case, the anxieties of the White community were now firmly focused on the Asians—the Chinese, Japanese and Indian immigrants—whose numbers, energy and foreignness thoroughly alarmed all classes of British Columbian society. As with the Black settlers forty years before, it was argued that the Asian communities were “unassimilable,” holding attitudes and values too alien to permit them an equal position in a White man’s country.

In fact, the Asian immigrants were, like the Black pioneers, disliked precisely because their attitudes and values were appropriate to a developing and fiercely competitive economy. They worked harder and longer, for less pay, than their White neighbours cared to. They saved their money and invested it wisely. They sacrificed to educate their children. If, like some of the Chinese immigrants, they came to BC only to build up a stake to take back home, they were no different in this than thousands of White prospectors had been in 1858 and in the Klondike.

The story of the Black pioneers in British Columbia began with an act of violence in a San Francisco boot shop. Perhaps it may be said to have ended fifty years later, in another act of violence.

In September 1907, a meeting in Vancouver of the Asiatic Exclusion League (at which a number of clergymen and community leaders were honoured to speak) led to an attack on Chinatown by a White mob. The race riot paralyzed the city—in fact, the whole province—for days, and it caused serious national and international repercussions. (Among other things, it launched the career of a young civil servant named Mackenzie King, who was sent to Vancouver to study the reasons for the riot. His eventual report also helped set Canadian policies that excluded South Asian immigrants and imposed harsh anti-narcotics laws.)

After almost a week of battles, strikes and random violence, a White man named McGregor wandered off Pender Street into Canton Alley, where several Chinese men were cutting wood. According to one account, he did nothing but casually kick at a piece of wood. According to another, he was drunk and assaulted one of the Chinese men.

What is certain is that as many as thirty Chinese men set upon him, and he was seriously stabbed in the head and face. A crowd of White passersby on Pender Street stood by and watched.

Before the White man could be killed, one person went into the mob in Canton Alley and rescued him. She was a Black woman—“a coloured woman of the half-world,” the Vancouver Province called her—who “jumped into the fray and managed to get McGregor into a door where she protected him from his assailants until the arrival of the police.”

We don’t know her name. But like all the Black pioneers of British Columbia, she was in her way a teacher. Many British Columbians have yet to learn what they taught.