Chapter Seven: “A most orderly and useful and loyal section of the community”

For the most part, Victoria’s Black settlers spent little time and energy in battling prejudice and seeking justice. Like their White neighbours, they were busy making a living, getting ahead and minding their own business. Mifflin Gibbs, for one, did extremely well in his first year—so well that he could afford to take time off for an extended visit to the eastern United States.

In Oberlin, Ohio, he married a girl from Kentucky named Maria Alexander, who had studied at Oberlin College from 1852 to 1854. Since the 1830s, Oberlin had been virtually the only post-secondary institution in the US that accepted Black and Native American students; Maria Alexander Gibbs and other Black Oberlin alumni were to have a significant influence on the history of British Columbia.

The newlyweds visited a number of Gibbs’s old abolitionist comrades, including Frederick Douglass, before making the long journey back to Victoria. In the next seven years Maria would bear their five children—most of whom would go on to notable careers.

For all their private concerns, the Black settlers were remarkably civic-minded. One of the first public projects they supported was the formation of a volunteer fire brigade. Firefighting was not yet seen as a government service; instead, public donations financed volunteer units. Membership was prestigious and not available just for the asking. To join a fire brigade cost a hundred dollars, but plenty of volunteers presented themselves.

The Black community, including the owners of some valuable and inflammable property, were generous contributors to the fund for the proposed fire brigade. In October 1859 the Hook and Ladder Committee met to plan the beginning of the firefighting service. Jacob Francis was there, and, as the Colonist reported, he

"remarked that as the French residents were represented on the Committee; and as the colored population had subscribed liberally and were largely interested in property here, he thought they should also be represented on the Committee. He therefore moved ‘that two from colored residents be added to the Committee.

The motion was seconded by Mr. Johnson; but lost.

"

The White residents who controlled the committee also controlled the membership of the fire brigade and rejected any volunteers they disliked. No Black person was accepted, though several volunteered.

The Black community then approached Governor Douglas with a proposal to form a volunteer militia unit. The idea had been in the air for some time; such units were then fashionable in Britain because of fears of a French invasion. During the Crimean War, Douglas had had to worry about possible Russian raids on the colony, and now a war scare was developing right on his doorstep—the so-called “Pig War” over control of San Juan Island.

Claimed by Britain and used by the HBC as a farm, the island had been occupied by US troops by the orders of General William Harney after an American settler shot a British pig in June 1859. Harney was acting without orders and seems to have seriously embarrassed the US government by his action. In one of his few misjudgments, Douglas had ordered the British naval forces at Esquimalt to take the island back. The officers stalled him until their commander, Admiral Baynes, returned to port. Baynes very sensibly refused to embroil Britain in almost certain war with the United States.

The dispute was to simmer for over a decade, but in its first few months it looked very serious. The British colonists were reminded of their vulnerability; the Americans in Victoria saw a chance to annex Vancouver Island and British Columbia to the United States.

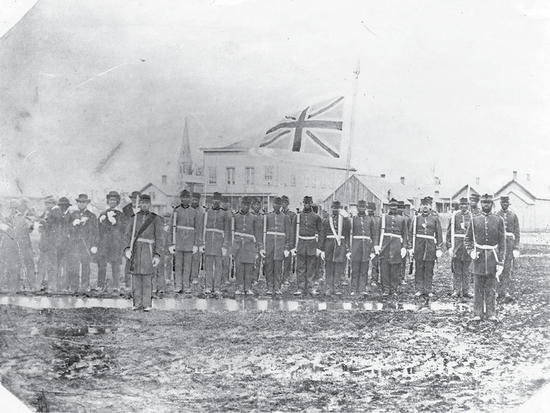

Douglas was always short of funds, so the Black settlers’ idea of a self-supporting volunteer unit was attractive. He gave his assent and recruiting started at once. As payback for their exclusion from the fire brigade, the organizers limited memberships to Black volunteers only. By the spring of 1860, between forty and fifty members were enrolled in the Victoria Pioneer Rifle Corps (also known as the African Rifles). The corps was not officially sworn in until July of 1861, but by that time it was already a well-known and popular organization.

James Pilton says the Pioneer Rifles originally consisted of forty privates, one sergeant, two lieutenants and a captain. Officers held their places by election. None of its members had previous military experience. However, they recruited a drill sergeant on HMS Swiftsure to teach them the basics.

The corps’ uniforms were reportedly very colourful: dress uniform was blue with white facing and pipeclayed webbing, while drill uniform was green with orange facing. Their headgear was flat peaked caps. Pilton believes the story is probably true that the uniforms were made from Hudson’s Bay blankets. Judging from a photograph taken of the unit in 1864, it looked as soldierly as any company in the US Civil War.

The Pioneer Rifles built a drill hall on upper Yates Street and later moved it to View Street. In good weather, however, the volunteers usually drilled on Church Hill or on Beacon Hill.

Dependent on some ancient and useless flintlocks on loan from the HBC, the volunteers asked Douglas for better weapons. Douglas took the appeal seriously, and in a letter to the Colonial Secretary in London, he wrote:

"A Volunteer Rifle Corps has been formed amongst the coloured population, which I have fostered to the best of my ability by encouraging them to proceed and by obtaining the services of a Drill Sergeant from Her Majesty’s Ships; and so great is the esprit exhibited by them, that they have built themselves a Hall, and pay the Drill Sergeant most handsomely for each instruction; but they want Firearms, and have applied to me to render them this assistance which at present I am unable to do. . . .

The smallness of the Colonial Revenue, and the infant state of the Colony will not admit of the necessary Firearms being procured by the Colony; I trust therefore that Her Majesty’s Government will extend their assistance in this matter; and if they will but promise 500 stand of arms, I will engage on my part to form a volunteer force that I can safely assert will be no discredit to the Empire.

"

His request was granted, and in the spring of 1862 he received 29 cases of rifles and 250 barrels of ammunition. A little later, 500 more rifles arrived. Evidently none of these reached the Black militia; its officers were still asking for them in 1864.

Meanwhile, a parallel White militia formed in the summer of 1861. The Vancouver Island Volunteer Rifle Corps included 150 men. This was in the early months of the US Civil War, and many Victorians must have imagined Britain being dragged into it. If the colony were to have to fight the Americans, its tiny militia units would have to fight as one. The Black volunteers assumed that the commanding officer of the White company would also command the African Rifles and argued that they should therefore have a voice in electing that commander. This idea was rejected out of hand.

Running a military is an expensive business, and the Black community quickly learned this. They raised money for the Pioneer Rifles by holding parties in the drill hall, and the women in the Black community made occasional donations. But it wasn’t enough, and late in 1861 Governor Douglas received the following appeal:

"To the Colonial Scty. Of V.I.

Sir

Hearing that the sum of £250 have been passed in the estimates of the year for the different Volunteers corps of the coloney

I have the honor to apply to you in behalf of the Volunteers Corps of colored men duley sworn in and called the Victoria Pioneer Rifle Corps for such portion of that sum as his excellency shall think fit to allow us.

I may be pardon for observing that this company has been regular and attentive in its drill and will be found wherever circumstances shall call for its employment fulley as efficient in the field and second to none in steady loyalty to the flag which it has adopted as its own—trust that you will be so good as to lay this our respectful application before his Excellency and further our request by your favorable interest.

I have the honor to be your humble obedient servant.

Fortune Richard

Capt. Of Victoria Rifle Corps

"

On December 9, 1861, Douglas responded by authorizing the payment of £45 to the Corps. This was about $250 in US dollars, out of about $1,250 reportedly budgeted for “the different Volunteer corps of the coloney.” No one else was in a position to claim such funding, so it’s unclear where the rest of the money went.

A few months later, Douglas was asked to supply a detailed list of the militia and volunteer units in the colony. By now the White Vancouver Island Volunteers had disintegrated in quarrels; the only forces ready to defend Vancouver Island were the Royal Navy and the Pioneer Rifles. The volunteers took the opportunity to appeal for more support:

"This Memorial from the “Pioneer Rifle Corps” to His Excellency Governor Douglas.

Humbly Sheweth.

That having been at a great expense, from the commencement to the formation of the Corps, to the present time, they humbly request that His Excellency, will be good enough to grant them, sufficient money from the sum voted in the Estimates, for this year, to carry out, the necessary alterations, and improvements to their Armory.

The size of the Building at present, used for a drill room is 20 × 60 Feet.

The Company propose to enlarge it, to 30 × 80 Feet, and to have it weather boarded, and hard finished. Also putting up a substantial Arm Rack &c. &c.

The cost of these necessary alterations is estimated to be about Seven Hundred Dollars ($700.)

The Company have the honor to enclose, a statement of their affairs, to the 31st July, from the commencement, shewing that they spent themselves nearly $1400 less the $250 they received from His Excellency.

They have now the honor to beg His Excellency to be kind enough, to take this into His early consideration, and to grant their request.

Fortune RichardWilliam Brown

Capt.Acting Secty.

"

Nothing came of this or later requests, but somehow the Pioneer Rifles managed to survive for several years and even to form the Victoria City Brass Band as an auxiliary.

The officers and men of the Pioneer Rifles took pride in their unit. During the 1861 visit of Lady Jane Franklin, a delegation from the volunteers paid a call on the famous widow of the lost Arctic explorer. Sophia Cracroft, Lady Franklin’s niece and travelling companion, recorded the meeting in a letter home:

"At 5 o’clock the Bishop [George Hills] came to be present at the visits of the coloured people who had asked my Aunt to see them . . . the first was Mr. Gibbs, a most respectable merchant who is rising fast. His manner is exceedingly good, & his way of speaking quite refined. He is not quite Black, but his hair is I believe short & crisp. Three other men arrived after him, & he took his leave soon after, having acted rather as spokesman for the others, who then explained that they were the Captain & other officers of a Coloured Rifle Corps, & the Captain proceeded to speak very feelingly of the prejudices existing here even, against their colour. He said they knew it was because of the strong American element which entered into the community, which however they hoped one day to see overpowered by the English one; —that they had come here hoping to find that true freedom which could be enjoyed only under English privileges, & great had been their disappointment to find that their origin was against them.

My Aunt sympathised with them of course, & said she knew their claims had been always maintained by the Bishop as representing the Church. This observation was eagerly taken up by the Lieut who said that but for the stand made on their behalf by the Bishop & his clergy, the coloured population would have left the colony in a body. We shd thus have lost a most orderly and useful and loyal section of the community. They naturally detest America, & this Rifle corps has been formed by them really with the view of resisting any American aggression, such as this San Juan alarm, still pending.

As he went out, the Captain said “Depend upon it, Madam, if Uncle Sam goes too far, we shall be able to give a good account of ourselves.” You can imagine how gratified the Bishop was by this emphatic declaration of their obligations to himself & his clergy.

"

It is uncertain how serious the officer was in claiming that the Black settlers had nearly left Victoria over the church dispute; no indication of such an attitude reached the newspapers. And while the morale of the Pioneer Rifles was no doubt high at the time, it is unlikely that forty or fifty ill-equipped militiamen could have resisted American professional soldiers.

Sophia Cracroft’s letter also noted other interesting aspects of Victoria’s Black community. She and Lady Franklin arrived in early March and found very acceptable lodgings in the home of Wellington Moses—“the very best in the place & really very tolerable—a tidy little sitting room & bedroom behind for my Aunt—the landlady giving up her own room (above) for me.”

Moses, born in England, had had an earlier connection with the Arctic explorer Sir John Franklin, as Sophia Cracroft remarked:

"He was very nearly going out with my dear Uncle—only his wife at last refused to let him go. [This must have been another wife, for Moses had married Sarah Jane Douglas in Victoria in December of 1858.] They are very respectable people. He is a hair cutter & has a shop—the naval people especially patronize him . . . & his wife has the reputation of being a first rate cook. . . . Mr. Moses calls himself an Englishman, which of course he is politically & therefore justly. She is a queer being, wears a long sweeping gown without crinoline—moves slowly & has a sort of stately way (in intention at least) which is quite amusing. Sometimes she ties a coloured handkerchief around her head like the American negroes (she is from Baltimore). . . . The language of both is very good. Mr. Moses said to Captn Richards when he was arranging about our being taken in, “The fact is, Sir, my wife is the best housekeeper in the country except yours.” Captn Richards begged he wld make no exception in favour of Mrs. R who he was sure cd not equal Mrs. Moses!

"

The English ladies toured the colony’s schools and were again reminded of the recent church dispute. Some White settlers had pressured Bishop Hills to segregate the church schools, “but the Bishop was not likely to give way upon such a point, and his firmness met with its reward—the threatened withdrawal of the other students never took place, and we saw the unmistakable descendants of negroes, in Mrs. Woods’ little school of 30, side by side with the English and American girls. The struggle has not been very long past, & at one time seemed serious.”

Sophia Cracroft’s observations show what seems to have been a typical upper-class English ambivalence toward the Black community: an indignant distaste for American prejudice, coupled with almost obsessive remarks about Black individuals’ appearance and behaviour—complete with hair texture, voice and manner of speaking.

Though White Americans periodically agitated for school segregation in Victoria, they got nowhere. Black and White students attended classes together and in general got along well. Edgar Fawcett, who came to Victoria as a boy with his parents, later recalled a fight between a Black pupil and a White one.

“I was mainly instrumental in bringing it about,” he wrote in his reminiscences, “and backed my man until the sponge was thrown up by the white boy’s friend.” The fight seems to have had no racial motivation, just juvenile bloody-mindedness. Fawcett was severely punished when his role in the fight came out, and he observed ruefully: “I got little sympathy at home when I told them I had been whipped for causing a fight between a white boy and a black boy named White.”

For all the discrimination they met, Victoria’s Black residents could rely on the law to protect their interests more effectively than it ever had in California. One dramatic proof of this occurred in September 1860, when the Black community learned that a runaway slave was being held aboard the American mail steamer Eliza Anderson, then in Victoria harbour.

The slave, a thirteen-year-old boy named Charles Mitchell, had run away from Major James Tilton in Olympia, Washington Territory. On September 24 he had stowed away on the steamer just before it left Olympia for Vancouver Island. He was discovered en route, and the vessel’s captain, John Fleming, had him locked up in a cabin. Fleming planned to keep him there until the ship returned to Olympia, but somehow word got out to the Black community in Victoria.

They immediately went to Attorney General Cary, who drew up affidavits and applied to Chief Justice Cameron for a writ of habeas corpus. The writ was directed to Sheriff Naylor, who was thereby empowered to take Charles Mitchell into custody and to bring him before the court.

Sheriff Naylor went down to the waterfront, just a few yards from the government buildings, and went aboard the Eliza Anderson to demand that the boy be handed over. Captain Fleming at first refused, though he knew he might be putting himself in trouble with the colonial authorities. But he also had to go home to Washington Territory, where Major Tilton awaited the return of his slave.

Unimpressed, Sheriff Naylor said he would break down the door of Mitchell’s cabin if it were not opened forthwith. Since Naylor was an enormous man who looked as if he could do the job single-handed, Fleming gave in.

Sheriff, slave and sea captain now came ashore and went directly to Chief Justice Cameron’s courts, where Cary waited to act as Mitchell’s counsel. After reading the affidavits the Black protestors had signed, Cary argued that British authorities had every right to board a foreign vessel in a British port and to take Mitchell out of unlawful custody. In any case, Cary went on, the mere presence of Charles Mitchell on British soil made him ipso facto a free man.

Cary’s precedent was the 1772 case of Somerset vs Steuart. James Somerset, a slave owned by Charles Steuart since 1749, had travelled with his master from the American colonies to London in 1769. Late in 1771, fearing he would be sold and shipped to the Caribbean, Somerset vanished—but was soon found and kidnapped by professional slave-catchers.

This was routine in 1770s London, but in this case, as in 1860s Victoria, a witness secured a writ of habeas corpus. A test of slavery’s legality in Britain followed, and the decision by Lord Chief Justice Mansfield established a radical principle: by simply setting foot on British soil, a slave became free.

Almost ninety years later, Charles Mitchell was about to walk as free as James Somerset. But Captain Fleming found legal counsel, and with the help of Attorney Charles Pearkes he composed and filed a protest against the sheriff—more likely to cover himself with his neighbours in Olympia than to influence Chief Justice Cameron:

"The said Sheriff threatened to force open the room in which the Negro was confined on board of said vessel. Whereupon the undersigned to prevent the destruction of property and in all probability much bloodshed opened the door of said room and upon doing so the Sheriff took the Negro from on board said vessel.

Now therefore the undersigned protests against the whole proceedings as illegal and a breach of international law, and demands the immediate delivery of said negro Charles that he may be returned to his master.

"

Cameron took little time to rule that Charles Mitchell should be set free, and was applauded by the audience. On the same day he had arrived a prisoner, Charles Mitchell found himself free. To Victoria’s Black community, it must have been exhilarating to win so swift a legal triumph after the endless delays of the Archy Lee case back in California.

While at least one Washington Territory newspaper protested Cameron’s decision, sentiment in Victoria was generally favourable. Amor De Cosmos relaxed his anti-Black campaign long enough to gibe at American hypocrisy; he also noted that since Victoria was a free port, “not even negroes can be kept in bond here.”

Charles Mitchell was soon enrolled in the Boys’ Collegiate School run by the Anglicans in the same “upper-room” Reverend Clarke had used during his short ministry. Here, six months later, he came to the attention of Sophia Cracroft, who mentioned in passing that his “history excited a good deal of attention in these parts. . . . He is not particularly intelligent.” What her evidence might be is unknown, but intelligent or not, Charles Mitchell was free.

When Black settlers themselves came in conflict with the colony’s laws, it was generally for trivial reasons, and they were treated as fairly as their White neighbours. A typical case came before the courts late in the summer of 1860. Under the headline “A Rumpus Among the Negroes,” the Colonist reported it at length, probably because it involved a racially mixed couple and had plenty of humorous human interest.

"Yesterday morning Timothy Roberts, a negro drayman, appeared in court to answer a charge of using disgusting language towards a buxom negress, named Elizabeth Leonard. Roberts came into court with his wife, a diminutive Irishwoman, who stood by her husband’s side during the investigation, and prompted him occasionally as he made his defence.

Mrs. Leonard said that last Sunday morning some of her chickens got over into Roberts’ yard, and that R. wrung their necks and used insulting language, calling her a ‘Black — ’ etc.

A witness, called to substantiate Mrs. L., testified that she saw Roberts twist the necks of the chickens, and Mrs. Leonard said to him, ‘That is an unliberal, unchristianized act.’ Roberts said, ‘Git out, you Black —,’ and told her to do something vulgar.

The Judge asked Roberts what he had to say for himself?

Roberts—You see, Judge, this ’ere woman, and all the other colored folks, is down on my wife because she’s Irish. I can’t help it because she’s Irish—’tain’t my fault. (Sensation in court, and slight hissing.) They call my wife Irish, and keeps a using insulting language towards her whenever she goes in the yard, and says I’m a nadgy-headed [Black person].

Mrs. Roberts—Your honor, I want pertection; but I suppose I must put up with undecent remarks because I lives in a low neighborhood. I am rebuked and reviled every time I go into the yard.

The Judge—Well, Roberts, you will have to find two sureties in 20 pounds sterling each to be of good behavior in future, or in default suffer one month’s imprisonment.

The negro, closely followed by his white wife, was then led off to prison, grumbling at his hard streak of luck. We learn that he afterwards furnished the bonds and was set at liberty.

"

Over a decade later, according to the 1871 Victoria census, Timothy Roberts and his White wife were still living on Yates Street. What became of Mrs. Leonard is unknown.

Racial tension was also involved in another case, when a Black teamster named Stephen Farrington charged three White men with assaulting him. One of the three, John Guest, was a notorious troublemaker who had been in numerous scrapes before.

"The complainant swore that he had been called a very bad name by Mr. John Parker while on his way to Esquimalt to meet the steamer, because he could not turn out and let Parker pass; that when they had all reached Esquimalt he went to Parker and remonstrated with him for his language, whereupon [Thomas] Burnes struck and knocked him down and Guest and [William] Baugh kicked him while he lay on the ground. As a proof . . . witness exhibited a black eye. He also swore that he was sober at the time of the row.

Several witnesses were called to prove that the complainant was drunk and abusive to the white; that Guest only struck after being assailed with a black-snake [whip] in the hands of a colored teamster; that Burnes, while the fight was progressing . . . remained a passive spectator, and that Bough was a long distance away. . . .

Solomon Stevens (colored) called as a witness for the prosecution, was proved to have been very abusive and in company with his friend Farrington behaved so outrageously and made so much noise as to cause Chief Justice Cameron, who chanced to be on the spot, to send a messenger to Victoria for a policeman. Mr. Pemberton according dismissed the case against all the accused.

"

Such incidents were predictable among teamsters and others accustomed to solving disputes with their fists. But the Black man who seemed to get into the most trouble with the law was a solid middle-class entrepreneur named Willis Bond. Born a slave in Tennessee in 1823, Bond had entered California as a “servant” and had earned enough to buy his freedom. He reached Victoria in the first days of the gold rush and went on up the Fraser River to Yale, where he and an English partner supplied water for mining operations. A few months later he returned to Victoria and began running a number of enterprises.

Bond’s first brush with the law was in early 1859, when he was charged with selling unwholesome food and counterfeiting flour brands. He was found not guilty, but a few years later he found himself in court again and again: he failed to pay an employee’s wages, he got into fistfights in the street, he wrecked a neighbour’s fence and he once obstructed Government Street for three days with a house he was moving.

For all his legal problems, Bond was better known as an orator. He even built a lecture room as an annex to a bar he owned. In this “Athenaeum Room,” he spoke on politics, economics and race, and sometimes debated issues with local celebrities.

Bond’s speeches were lively, well-attended events, but they sometimes got out of hand. On one occasion, he spoke against giving a government subsidy to the Mechanics’ Institute, which refused membership to Black people. Someone in the large crowd of listeners threw pepper on the stove, driving the audience upstairs. Bond refused to leave however, even though someone tossed a string of firecrackers into the room. His audience finally returned but was again dispersed with pepper and firecrackers.

Despite these incidents, Bond remained in Victoria until his death at sixty-eight in 1892. His wife, Martha, died there in 1903, aged eighty-three. Their daughter (also named Martha) was listed in the 1901 Victoria census as a nurse. She had been born a slave in the US in 1852.

Over a century and a half later, most of the quarrels and annoyances that beset Victoria’s Black residents in the early 1860s seem comfortingly trivial: a few brawls, a few teapot tempests played for laughs by the newspapers of the time. Of course these incidents provoked genuine sorrow, anger or triumph among the Black residents, but they did not poison the whole community’s atmosphere as later events would.

Most of the anti-Black feeling in the British Northwest was confined to the muddy streets of Victoria. In the goldfields of the Cariboo and on Saltspring Island, Black and White pioneers lived and worked together with relatively little friction. But in subtle ways, racism touched them as well.