Chapter Nine: “They are the uncrowned kings”

Violent and dramatic events marked the settlement of Saltspring Island; Black people were involved in most of them. From our perspective they seem epic figures, enduring hardships and giving immense, patient love and work to their land. But the experience of the Saltspring Black community was not as free of prejudice as it once seemed.

Confusion even exists about the date and manner of the first Black settlers’ arrival on the island. Bea Hamilton, in her book on Saltspring, says that nine men landed together in the summer of 1857 to found a Black colony on the uninhabited island—but hardly any Black people lived in the British Northwest before 1858, and Saltspring never had a Black “colony.” For a time, though, it had a remarkable number of Black settlers.

The island’s development was inevitable. By the late summer of 1858, many miners were already back in Victoria from the Fraser diggings. Too poor to resume mining or to return home, they would somehow have to support themselves on or near Vancouver Island. At the same time, the colonial government was eager to establish a stable, self-supporting population. As Ruth Sandwell says in her book Contesting Rural Space: Land Policy and Practices of Resettlement on Saltspring Island, 1859–1891, nineteenth-century governments saw farming as the best possible use of “undeveloped” land.

A Scottish-born lawyer, John Copland, had spent some years in Australia and was now especially concerned about the plight of other Australians in the British Northwest: many were capable farmers who could not get land. Settlement was legal only on land the Crown had bought from the Indigenous nations and surveyed, which cost an absurdly high five dollars an acre.

Since Douglas was always short of money, he had not been able to buy and survey enough land to meet the new demand, much less sell it at a reasonable price. Copland therefore pressured the government to permit “pre-emption” of unsurveyed land by settlers who would not have to pay until they were prosperous enough to buy it.

Saltspring was Copland’s favoured area for settlement under this “no down payment” system. It was uninhabited (though the local Cowichans paid it seasonal visits and considered it part of their traditional territory). The Crown therefore thought it had clearer title to it than it would to Indigenous-occupied land. Saltspring was mountainous but well watered, with many apparently good farming areas. Its climate was moderate, and it was relatively close to the new farms of the Saanich peninsula, north of Victoria. The island was rich in game; clams and mussels grew thickly along its shores, and fish were plentiful.

Saltspring’s disadvantages were less obvious. The Cowichan people, living nearby on Vancouver Island and other adjoining islands, resented the intrusion of newcomers on their land. Though geographically close to Victoria, Saltspring was accessible only by occasional steamers or by dangerous canoe trips. Game animals were the prey of wolves, bears and cougars that would soon learn to attack domestic livestock.

In practice, pre-emption would benefit a few, while providing most with a temporary opportunity to live off the land without paying for it. But it would also create a new, multiracial community.

A considerable number of Black pioneers seized the opportunity to pre-empt land on Saltspring Island. As early as July 26, 1859, twenty-nine settlers received government authorization to take up claims on “Tuan Island,” as Saltspring was sometimes called. Several of these were Black, but only one—Armstead Buckner—was among the seventeen who left Victoria the next day to occupy their land.

Buckner settled north of Ganges, near St. Mary Lake; other Black settlers soon followed him. They included Abraham Copeland and his son-in-law W.L. Harrison; William Robinson, a gentle and religious man; John Craven Jones, the oldest of the Oberlin-educated Jones brothers; Fielding Spotts; William Isaacs; Levi Davis; Daniel Fredison; and Hiram Whims. Louis and Sylvia Stark arrived in 1860 and soon became prominent in the community.

The Black community was only one among many racial and national groups: American, English, German, Portuguese and Hawaiian settlers also pre-empted land on Saltspring. Being among the early arrivals, Black pioneers took some of the best land near Buckner’s property. This was to have significant consequences.

In the first edition of this book, I argued that the Black settlers on Saltspring were generally scattered and integrated among their neighbours. But Sandwell’s recent research shows that they tended to cluster on the good land around Vesuvius Bay and St. Mary Lake, on the northern end of the island. This should have given them an advantage over later settlers, who had to settle for less-useful land. Instead, Sandwell argues, it may have made them targets.

When settlers invested so little in their new property, it was easy to abandon it. Many of the settlers left their claims after one winter, but most of the Black settlers did well enough to bring their families to the island. For a time, therefore, they increased more rapidly than did other groups. In 1861, Rev. Ebenezer Robson visited Ganges, the largest of Saltspring’s few small settlements. He noted in his diary: “There are in the settlement 21 houses on the same number of claims. Four of the houses [are] inhabited by white people and the remainder by colored people. I preached in the house of a colored man in the evening to about 20 persons all colored except three and one of them is married to a colored man.” (This was almost certainly the Irish wife of Henry W. Robinson, who was born in Bermuda.)

This was a temporary predominance. As settlement continued, White arrivals soon outnumbered the Black settlers. Outwardly, the White pioneers showed little prejudice toward their neighbours. When Mrs. Lineker—wife of an Australian settler and shopkeeper—refused to worship in the same room with Black churchgoers, Reverend Robson found her attitude unusual: “Poor woman she says some people might do it but she has been brought up so she cannot—was the daughter of a Church of England clergyman.”

This apparent egalitarianism had its advantages. For settlers trying to clear land, plant crops and look after their families, help from neighbours would have been essential—whatever the neighbours’ race or class might be. On an isolated island with a preponderance of men, interracial marriages took place, though not as often as legend has it.

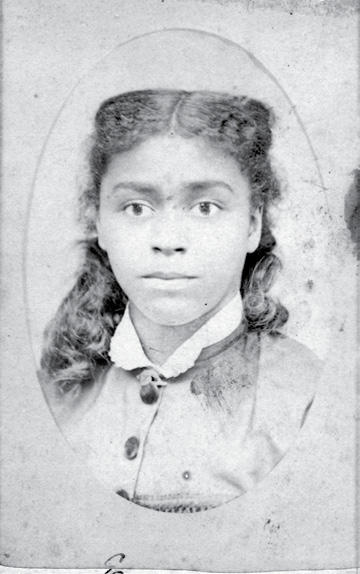

That legend doubtless owes much to John Norton, who was to become a patriarch on Saltspring. Born in the Azores, Norton arrived on the island in 1861 at the age of thirty-seven. In 1873, recently widowed and with two small children, he married Annie Robinson, one of the two children of Henry and Margaret Robinson. Annie had been born in San Francisco in 1856; she had arrived in the British Northwest with her parents in 1858, making her one of the youngest of the Black pioneers.

Annie Norton was eighteen or nineteen when she bore the first of her own twelve children; she died in 1903, at forty-six, just four years after giving birth to her last child. Norton became one of the most successful farmers on the island, dying in 1911 at age eighty-eight. Provincial marriage records show several Norton children as having married persons who do not appear to have been part of the BC Black community.

(It is worth noting that early census records and vital statistics are not always reliable: in the 1901 census, none of the Nortons are described as literate, or even as speaking English. This seems unlikely given the family’s financial success. Another record gives Annie Robinson Norton’s birthdate as 1836—clearly a transcription error by some census clerk.)

Charles Irby, a Black historian, has cited other cases of interracial marriages on Saltspring, including one in which a White Englishman married an Indigenous woman; one of their daughters married a Black man, and one of the daughters of this marriage in turn married yet another White man. Irby also quotes another Saltspring pioneer as saying that in one Black family “all the boys married white girls, and all the girls married white boys.”

This was to have some long-term consequences. Ruth Sandwell notes that “in more than a quarter of all households on Saltspring Island in both 1881 and 1891 the husband and wife had different ethnic backgrounds. Children from these marriages made up almost 50 per cent of the children on the island in 1881 and just under 30 per cent in 1891.”

But Sandwell shows that tension did exist between Black and White settlers. Some of it was due to the Black settlers’ early arrival on the island, enabling them to pre-empt some of the best farmland. Jacob Francis, who had been involved in the Victoria elections controversy, had taken land on the island. In 1863 he left an associate on the property and filed a leave of absence. But the associate left the claim without telling Francis. As the law permitted, three months later a neighbour formally signed a declaration that the claim had been abandoned and occupied it. Francis lost his right to the claim and whatever he had spent in improving it.

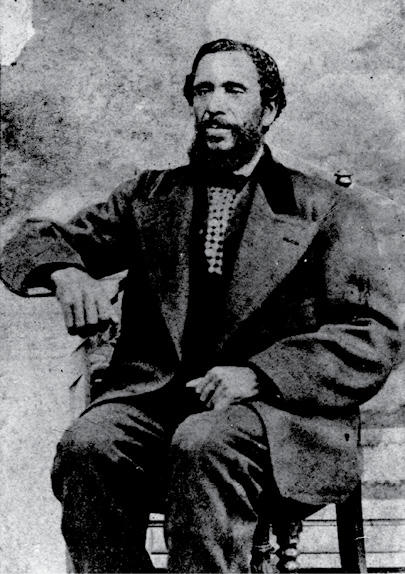

The Stark family

By then, the Stark family had already had its share of difficulties, but it had also planted deep roots on Saltspring Island. From our perspective in the twenty-first century, Louis and Sylvia Stark seem larger than life. They faced challenges we would shrink from and overcame them with fewer resources than we would consider necessary. But they were also typical of their time and place.

We owe much of what we know about them to the memoirs of Sylvia Stark, written by her daughter Marie Albertina Wallace. The memoirs are an extraordinary document, though not always reliable.

For example, according to the memoirs, sometime in 1858 or 1859, a group of Black settlers reportedly asked Governor Douglas for permission to found a colony, but he refused because he preferred a multi-racial settlement on Saltspring. It’s an intriguing story, but we have no confirmation of it.

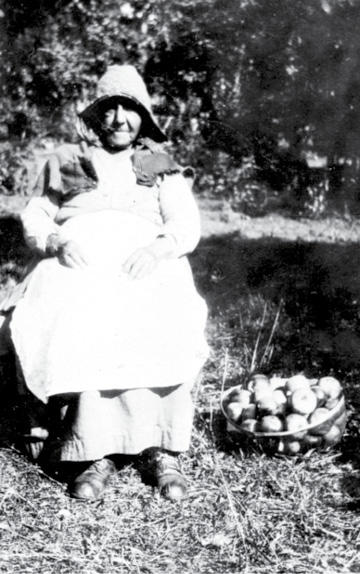

Elsewhere in the memoirs, Sylvia says six Black families had already settled on Saltspring when the Starks arrived in the summer of 1860: “She said there were two old colored people known as Grandpa Jackson and Grandma Jackson; Grandma Jackson was 112 years of age and Grandpa Jackson was 114 years of age. They did not stay long on Saltspring.” Again we have no confirmation of this, though Sylvia herself was to live well past a hundred.

Sylvia Estes was born in Clay County, Missouri, in 1839. Her parents were slaves; her father, Howard, had taken his family name from that of his owner, a Scottish man named Tom Estes. Howard’s wife, Hannah Estes, and their three children—Agnes, Jackson and Sylvia—were the property of a German baker named Charles Leopold.

Leopold was not a stereotypical slaveholder: he respected the abolition movement and once risked injury to prevent a race riot at an anti-slavery meeting. His wife, however, treated their slaves badly. She and Hannah Estes sometimes quarreled, and after one kitchen argument, Leopold exasperatedly chastised them both. (Sylvia also claimed that the young Harriet Tubman was one of the Leopolds’ slaves, which was simply untrue: Tubman was a slave in Maryland.)

Whatever his personal reservations may have been about slavery, Leopold demanded work from his own slaves. Sylvia’s earliest memories were of helping her mother dry dishes and of looking after the Leopolds’ children.

To be a child in slavery was to live in fear. Sylvia rarely left the Leopold property, having been warned of men who kidnapped Black children to sell in the South. Mrs. Leopold regularly bullied her, and she had to care for her master’s children when she herself was sick. Visits by her father were rare events.

But her parents raised her with love and firmness, and she even learned to read (though it was illegal) by being with the Leopold children as they did their schoolwork.

In 1849, Tom Estes sent his sons and his slave Howard to California with a herd of cattle. Tom Estes promised to give Howard his freedom for a thousand dollars. He agreed to let him work in California to earn the money. But when Howard sent the money, his master reneged. Howard sent another thousand dollars, this time in care of Charles Leopold. After a court battle, Tom Estes was forced to send Howard his “free papers,” while keeping most of the second thousand dollars.

By the time Howard Estes returned to Missouri early in 1851, his daughter Agnes had died of scarlet fever, and Sylvia had nearly died also. After some haggling with Leopold, Estes bought his family’s freedom: a thousand dollars each for his wife and son, and nine hundred dollars for Sylvia. Since Leopold had been offered fifteen hundred dollars for Sylvia alone, he showed that he had at least some family values. (Howard Estes, given his ability to raise such sums, must have been a skilled worker and an astute businessman.)

Together for the first time, the Estes family settled down on forty acres in Missouri to raise pigs and chickens. But like other Black farmers, they began to be harassed by White nightriders. Missouri was clearly not a safe place for free Black people. When Leopold decided to drive a herd of cattle to California, he asked the Estes family to come along as paid help. They agreed.

The journey took six months. Once in California, the Estes and Leopold families went separate ways. Sylvia’s family settled in Placerville, some sixty miles from Sacramento; they grew fruits and vegetables and Hannah Estes took in miners’ washing. They prospered, and Sylvia was to remember those years in California as the happiest of her life.

Sometime in the mid-1850s, she met and married Louis Stark, the son of a slave and her White owner. Stark had tried a number of careers before turning to dairy farming, and—like his father-in-law—he was doing well. But the worsening racial climate in California led both men to decide to emigrate to the British Northwest.

Estes sold his farm and took his wife and Sylvia to San Francisco, where they embarked on the steamer Brother Jonathan. Louis Stark and Jackson Estes, meanwhile, drove fifty head of cattle north. The families reunited in Steilacoom, Washington Territory, and went on together to Victoria. After several trips to outlying areas, Estes bought a farm in Saanich while Stark pre-empted land on the north end of Saltspring.

Sylvia by now had two small children, Emma and Willis, and was five months pregnant again when Louis brought her from her father’s farm to their new home on the island. As she recalled it in her memoirs, the day of their arrival was a violent and terrifying one.

The family reached Vesuvius Bay on the northwest side of Saltspring on a bright summer day in 1860. They had brought fifteen dairy cows, which had to be lowered from the steamer by ropes and then left to swim ashore. The cows then plodded up the trail that led to the interior of the island.

Meanwhile the Starks climbed down rope ladders from the deck of the steamer to two canoes. The paddlers, a local Cowichan man and his wife, then took them ashore with their belongings. With them went a Hudson’s Bay Company trader named McCauley, who offered to stay with Sylvia and the children while Louis went up the trail to get help moving their goods to the cabin. The steamer left, and the little group was left alone on the beach.

As they waited, the Cowichan couple saw canoes enter the bay—at least seven of them—paddled by Haida crews. The Cowichan woman disappeared into the woods while her husband sat unmoving, evidently paralyzed by fear. The Haida, residents of Haida Gwaii, had for centuries used their nautical technology to both trade and battle with other coastal peoples.

As the Haida paddlers brought their canoes ashore, Sylvia could see that each canoe carried a cargo of furs. The northerners were en route to Victoria to trade. They examined the Starks’ belongings with interest. One of them then turned to McCauley, waved a knife in his face and asked in English: “Are you afraid?”

Pale and trembling, the trader said he was not. The Haida traders then offered to take the Starks’ belongings up the trail. McCauley, who spoke their language, explained that Stark had already gone for help. Sylvia, meanwhile, sat on a log with her two children—Emma was about four and Willis was three—and prayed. “What will become of my children when they kill me?” she wondered. The Cowichan guide sat terrified nearby, not daring to look up.

When McCauley said he was going to Thomas Lineker’s house at Ganges, the Haida traders offered to take him. He accepted, and the canoes set out almost at once. But the Cowichan woman had taken her canoe across the narrow strait to a village on Penelakut Island (then known as Kuper Island), and had told them of the Haida paddlers’ arrival. A war party set out at once and overtook the Haida traders as they were paddling down the eastern side of Saltspring Island toward Ganges.

McCauley begged the northerners to put him ashore, but the Haida paddlers decided to try to outrun their pursuers. They failed. The Cowichans surrounded their enemies, but after learning that McCauley was their passenger, they allowed the Haida group to take him to Ganges.

“We will not kill the white man,” they called to the Haida paddlers, “but we will kill you.”

According to Sylvia Stark, the Haida and Cowichan warriors met in a fierce battle on the bay after McCauley had been put ashore. If her account is accurate, McCauley must have been involved in two such battles that summer. On July 9, 1860, Thomas Lineker wrote to Governor Douglas to describe a massacre that had just taken place virtually on his doorstep:

"Sir

At a meeting of the Settlers of this place I was deputed to address Your Excellency on the Subject of the Indians.

I beg therefore to acquaint Your Excellency that on the 4th of July last, at noon, a canoe with nine men, two boys, and three women of the “Bella Bella” [Heiltsuk] tribe came in her with a person named McCauley who had business with some of the settlers. While he was talking with me, the Cowichians numbering some fifty, who were encamped here (& who on the arrival of the Bella Bellas manifested an unfriendly spirit, but afterward appeared friendly) commenced firing, a general Fight ensued which lasted about an hour, and ended in the Cowichians killing eight of the others, and carrying off the women and boys as prisoners, the fight occurred so close to my house, that I sent my wife and family into the woods for safety, during the night one of the Bella Bellas came to me, wounded. I pointed out a trail which would lead him to the Northern part of the Island, hoping he might get away. I felt I could not give him shelter without being compromised in this murderous affair. Two men have just arrived from the other side of the Island, who inform me that a week since some Northern Indians took two of another tribe out of their boat and cut their heads off.

. . . Considering their defenceless position the Settlers trust that your Excellency will deem it expedient to afford them such protection as you in Your wisdom may think necessary.

"

Clearly, the Stark and Lineker narratives have enough in common to suggest that they deal with the same incident. It may be that only the canoe carrying McCauley actually entered Ganges harbour, where its crew encountered the Cowichan people on land rather than on the water. Lineker’s eyewitness account, written just after the massacre, is presumably more reliable than Sylvia Stark’s account of a battle she did not see. But we have no reason to doubt her own eyewitness account of the Haida traders’ arrival on the beach at Vesuvius Bay. Neither she nor Lineker was likely to confuse Haida and Heiltsuk people, and McCauley, as a trader, may well have travelled into Ganges with two separate groups in a brief space of time. Many northern Indigenous nations visited Victoria each summer, and no doubt they often clashed with the local nations; Lineker mentions the reported murders of two locals by northerners.

We may never know the precise truth about the Indigenous battles of 1860, but it is certain that they did take place, and that Black and White settlers alike were frightened by the threat of entanglement in Indigenous conflicts.

The Starks, however, faced more immediate problems. When Sylvia and her children finally reached their new home, they found only a rough log cabin, still lacking a roof and a door. Neighbours helped Louis put the roof on, and Sylvia hung a quilt in the doorway. Still badly shaken by the incident on the beach, she was despondent and lonely. She later recalled three-year-old Willis trying to console her: “Don’t cry, Ma. Let’s go home.” Home to him was California.

Nevertheless, the Starks persisted. Louis’s first job was to clear his land, and he had little to do it with but some crude tools and his own ingenuity. To uproot stumps, he improvised an ox-drawn plough made from a V-shaped tree trunk. He also began a fruit orchard and planted some wheat. In addition to their cows, the Starks raised chickens, turkeys and pigs; though the turkeys eventually went wild, and bears preyed on the pigs, the family began to feel it had gained a foothold.

Less than a year and a half after their arrival, Reverend Robson visited them and was impressed by their success:

"They with their children 3 in number are living on their own farm. It is good land and they pay only $1 per acre for it. Mr. Stark has about 30 head of cattle. He sowed one quart of wheat near his home last winter and reaped 180 qts in the summer. One grain of wheat produced 2360 grains on 59 branches. . . . His wife who was converted about 2 months ago filled my sacks with good things—4 lbs fine fresh butter, 2 qt bottles new milk. Mr. Stark gave me some of his large turnips.

"

His liking for the Starks was reciprocated: Sylvia later recalled him as a pleasant and helpful house guest. Offered the Starks’ best bed, he insisted on sleeping on the floor; he also helped with chores—chopping wood, hauling water and even churning some of Sylvia’s “fine fresh butter.”

Her conversion, in the late summer of 1861, had helped Sylvia to endure the loneliness and hardship of pioneer life. Her husband seems to have lacked her religious faith and to have disliked the sight of his wife praying; she therefore went alone into the woods to pray. Robson noted in his diary that Stark was not as religious as he might have been, “and yet there are worse men than him in the church.” (Some years later, Stark would bitterly protest that his neighbours had built a stretch of road that left his property isolated. They had done the work on a Sunday, when he couldn’t join the work party because he was observing the Sabbath.)

All told, the Starks had seven children. Emma Arabella (also known as Emily) and Willis were the oldest. Soon after the family’s arrival on Saltspring, Sylvia gave birth to John Edmund, and another son, Abraham Lincoln Stark, was born in 1863. Hannah Serena was born in 1866, Marie Albertina in 1868 and Louise in 1879.

John Craven Jones, Saltspring’s schoolmaster

Reverend Robson urged the settlers to establish a school, and they did so by 1861. It was an unbarked log cabin in the Central Settlement that served as both schoolhouse and church. William Robinson taught Sunday school there. Another Black settler, John Craven Jones, used the cabin three times a week for regular classes and then walked up to Begg’s Settlement to teach another three days. He was to teach all the island children for almost ten years without pay.

Jones came from a remarkable family. His father, Allen Jones, had bought his family’s freedom in North Carolina for the enormous sum of five thousand dollars. He had tried to establish a school for Black children there. Local White residents burned it down three times.

Moving their family to Oberlin, Ohio, Allen and Temperance Jones saw four of their sons graduate from the college. The oldest, James Monroe Jones, moved to Chatham, Ontario, where he became a renowned gunsmith. (One of his six children, Sophia, was born in Chatham in 1857 and graduated from the University of Michigan in 1885 as the first Black woman doctor in North America.)

Three other sons came to the British Northwest in the gold rush. John Craven Jones stayed on Saltspring, while his brothers William Allen and Elias Toussaint moved on to the mainland. Elias worked as a gold miner; William not only mined but also worked as Barkerville’s dentist, “Painless” Jones. Both eventually retired to the US.

John Craven Jones was widely admired and respected on Saltspring Island, and though his teaching left him little time to look after his farm, his pupils’ parents saw that he was looked after. (Jones had a young assistant, Frederick Douglass Lester, born in the US in 1845. Frederick may have been a relative of Mifflin Gibbs’s partner, Peter Lester; he was a house carpenter in Victoria in the 1880s, with a wife, Octavia, who had been born in the US of French parents.)

In her history of Saltspring Island, Bea Hamilton claims that John Jones persuaded his fellow Black settlers not to arm themselves or to retaliate against attacks by Indigenous peoples. He is thus credited with preventing the massacre that such retaliation would have provoked. It is a good story, but unpersuasive.

First of all, every farmer needed a gun for hunting and pest control and would have laughed at anyone asking him to get rid of it. In fact, lead shot and gunpowder were Saltspring’s chief imports in the early 1860s. Secondly, the story is based on a legend that the Cowichan people singled out Black settlers for special harassment, and would have risen en masse to avenge any injury done them by a Black person.

Black settlers were indeed robbed, threatened and sniped at by Indigenous persons, but we have little evidence that this was due to a widespread Indigenous hatred of Black people in particular. The Cowichan people were understandably resentful of all encroachments on their territory, and some of them considered any unguarded cabin a fair target. Many farmers—Black, White and Polynesian—saw their crops vanish overnight, picked by Cowichan individuals passing through.

But it is also true that many of them got along quite well with the settlers and continued to pick berries and hunt on the farmers’ land just as they had always done.

From contemporaneous accounts, especially Sylvia Stark’s, it appears that a few individual Indigenous people were responsible for most of the conflicts with Saltspring’s pioneers. On one occasion, five of them came unannounced into the Starks’ cabin and began to examine everything in it—even counting the blankets on the bed. One of them took Louis Stark’s rifle from the mantel; knowing it was loaded, Stark tried to take it away from him. In the scuffle, the gun went off, putting a bullet through the roof. Evidently frightened, the people left.

One Cowichan man named Willie was especially notorious. He once tried to snipe at Stark, who saw sunlight glint off Willie’s gunsight. Himself armed, Stark called out to Willie by name. Willie knew Stark’s reputation as an excellent shot and realized that if he missed, Stark would not miss him. He put up his rifle. Willie was later a prime suspect in at least one murder of a Black settler, Giles Curtis, and in his old age boasted of having killed thirty people.

Such incidents may have been inspired by the Cowichan people’s alarm over the loss of their lands. But the key factor in the growing violence between Indigenous people and settlers was a disaster that shattered British Columbia’s Indigenous societies for generations.

The smallpox pandemic

The winter of 1861–62 was one of the worst in the history of the Northwest Coast. For weeks the Fraser was frozen far upstream from its mouth, and on Saltspring Island over a hundred cattle died for lack of feed. Then, in March of 1862, a man arrived in Victoria from San Francisco. He had an advanced case of smallpox.

As usual, thousand of Indigenous people were encamped around the town. Many were doubtless in poor health already after living in tents through the bitterly cold winter of 1861–62. The newspapers warned of the epidemic’s impact on Indigenous people, but as usual the authorities did nothing. Then, when smallpox did appear in the camps, the government panicked and ordered all Indigenous visitors to go home.

The BC coast had seen smallpox before. Some historians speculate that it had reached the coast not long before Captain Vancouver arrived in 1792, and it may have come up from Mexico even earlier. But this outbreak was a catastrophe on a scale not seen again until the Spanish flu in 1918–19.

Within days, smallpox had spread from Victoria to Alaska. Wilson Duff, in The Indian History of B.C., estimates that twenty thousand people—one-third of his estimate of the coastal Indigenous population—died in the next three years.

The White settlers did little if anything to help the Indigenous victims. Lt. Edmund Hope Verney of HMS Topaze, a well-educated and relatively enlightened man for the time, nevertheless described the tragic events to his father in a shockingly callous manner on May 15, 1862:

"The natives are hideously ugly and atrociously dirty: their customs are beastly, manners they have none: there has been a compulsory exodus of them which is still going on, on account of the small-pox which is raging fearfully among them; as soon as they clear out their houses are burnt down: the bishop and one or two of his clergy have been working most assiduously among the wretched dead and dying of this loathsome disease, which shows itself among these poor wretches in its most malignant form.

"

As it ran its course, the epidemic left Indigenous societies in ruins. The old hierarchies were gone. As high-status positions became vacant through the deaths of their occupants, younger men rose rapidly. They lacked experience in dealing with the colonists and had no doubt been traumatized by the pandemic. The old social limits were gone.

The Stark family, ironically, suffered from the epidemic by their efforts to avoid it. Louis Stark had himself and his family vaccinated as the smallpox spread. In his case, the vaccination—together with the effects of working in cold, wet weather—made him ill. For several days he was so delirious that Sylvia could not even leave him long enough to fetch Dr. Hogg, Saltspring’s only physician.

While Louis’s arm swelled, Sylvia had to milk fourteen cows, look after the pigs and chickens and do all her usual household chores. She tried but failed to reduce the grotesque swelling of her husband’s arm.

At last, when Louis was again aware of his surroundings, Sylvia left Emma to look after her little brothers. She left strict order that Willis, then five, was not to be allowed outside for fear of cougars. After a long walk to reach the doctor, she returned with him in Armstead Buckner’s cart. Dr. Hogg wrapped the arm in cold clay, which reduced the swelling. Though the affected arm was thereafter smaller than the other, Louis Stark regained his strength.

Violence on Saltspring Island

In the spring of 1863, while smallpox raged up and down the coast, three murders alarmed the Saltspring settlers. Two men named Brady and Henley were attacked as they slept on an island near Saltspring; Brady died of his wounds. Then a German man named Marks and his young married daughter were killed on Saturna Island.

HMS Forward patrolled the Gulf Islands in search of the killers. An Indigenous man told the ship’s officers that the murderers were in Penelakut, a village on what was then known as Kuper Island (now Penelakut Island). The Forward anchored off the village and sent a message ashore, demanding the surrender of the suspects. The only response was a rifle shot that killed a sailor.

The gunboat then methodically shelled the village to ruins; the Starks, on their farm not far away, could hear the bombardment. According to Sylvia, a shore party then searched the village. They found only a blind old woman; the rest of the inhabitants had fled into the woods. The authorities eventually found the culprits in the Marks killings, however, and hanged them.

Another shocking crime startled the island in the summer of 1864. The Colonist reported it as “The Violation Case” on July 29:

"The investigation into the charges preferred against the colored man William Francis Kerr, by Henry Robinson, for a gross outrage alleged to have been committed upon the persons of his daughters, three helpless little girls, named Anna, Catherine, and [Margaret] Robinson, of the tender ages of 8, 6½, and 4 respectively, took place yesterday in the Police Court, but the enquiry revealed particulars far too revolting and disgusting for publication in our columns, suffice it to say that after hearing the testimony of the father and mother of the much abused children and that of two of their daughters (who were evidently frightened and spoke somewhat incoherently); also Mr. Sampson, constable of Salt Spring, and Doctors Helmcken and Davie, the magistrate committed the prisoner for trial in the case of Anna Robinson, the oldest daughter, but dismissed the other two charges.

Previous to committal the prisoner made the following statement:

“Worked for Mr. Robinson the last two months at Salt Spring; I commenced working on 30th May and worked until last of June and then came to Victoria. I stopped a few days and returned on the 6th July, and have worked ever since clearing up land, etc., for Mr. R., who was always interfering, saying I did not work enough, and should work for six months without sharpening my ax. On Tuesday when I was arrested I went up to the house and saw two or three men armed with guns and rifles, and Sampson arrested me; I did know what for, and thought it was a second charge made by Burnside, with whom I had some trouble in the police court. I never had any connection whatever with the children. I did not know except from appearance whether they were males or females, and have never been nearer to them than when their mother has been present and I was teaching them their lessons. I am not guilty.”

"

For some years thereafter, lawlessness on Saltspring was relatively minor: thefts, assaults and occasional snipings. Then, in less than a year and half, three Black men died.

Ruth Sandwell notes that “between August 1867 and December 1868 the tiny community of Vesuvius Bay on Saltspring Island, populated by about twenty-five families, was the scene of three brutal murders. All the victims were members of the island’s African-American population, and coastal Natives were widely believed to be guilty of all three murders.”

As we have seen, Cowichan people and settlers had sometimes experienced violence. But by the time of the murders, the Cowichan people were benefiting from economic relations with the settlers—and several Cowichan women were married to settlers.

So the deaths of the Black settlers in 1867 and 1868 don’t make much sense in conventional terms. But when Sandwell asks, “cui bono,” who benefits, a new explanation emerges.

Surprisingly, we don’t even know who the first victim was. The Colonist in 1867 simply reported that a dead man had been found, partly buried in an old stone quarry. He had been shot, but his identity was not established and the murderer was never found. The only other record of the case, Sandwell tells us, was in the Colonist in December: “The remains of the colored man found murdered at the stone quarry . . . have never been interred, and . . . the bones lie there bleaching on the ground. What shocking inhumanity!”

The death of William Robinson (apparently no relation to Henry W. Robinson), stirred much more concern. Robinson had lived alone in a windowless cabin, and in the spring of 1868 he had told his Sunday school class that he would meet them only one more time. His wife had refused to join him in the West, so he would be returning to her.

During that week, a man arrived at Robinson’s cabin in Vesuvius Bay to deliver some goods. The windowless cabin was locked, and no one answered when the man knocked.

Trying again the following Saturday, the man pried out some of the clay packed between the cabin’s log walls and peered inside. He saw a man’s booted feet. The constable was sent for, and a log removed to permit entry.

William Robinson had apparently been shot in the back, at point-blank range, while eating dinner. His killer had stolen a shotgun and some clothes. No suspects could be identified.

Then, in December 1868, a third Black man was killed. Giles Curtis had been working for another Black man, Howard Estes—the father of Sylvia Stark. Again the victim had died in his cabin, a bullet wound in his temple and his throat cut, though nothing had been stolen.

The settlers were now enraged as well as frightened, since the authorities seemed so slow to take steps against these killings. The government offered a $250 reward for Curtis’s killers, and sent HMS Sparrowhawk to seek information in the Indigenous villages nearby.

According to Sandwell, John Norton provided some hearsay evidence: he told officials that he had been threatened by two Indigenous persons on the night before Curtis’s murder. Norton’s claim was not confirmed, but public opinion in the colony assumed that Cowichan people had committed the killings. Sandwell cites just one Colonist article reporting evidence that a White man had killed Curtis.

Meanwhile, a Cowichan individual denounced another Cowichan man, Tschuanhusset, for William Robinson’s murder. In April Tschuanhusset was arrested. He confessed and was hanged in July.

Sandwell points out that even the colonial government was struck by the lack of physical evidence. The killer had presumably taken Robinson’s property, but Tschuanhusset had none of it. A second search of his home turned up an ax that may or may not have belonged to Robinson. The shotgun was nowhere to be found. If the ax really was the purpose of the murder, Tschuanhusset paid a high price for it.

It may be, Sandwell suggests, that William Robinson was killed not for an ax but for his land—a very valuable property including the only spot on the west side of Saltspring where the mail steamer could dock. Somehow Robinson’s land had been taken over by another Black settler, Fred Lester, in some kind of quiet auction. Sometime in the 1870s it passed to another Black man, Abraham Copeland, but a Portuguese settler named Antoine Bittancourt contested Copeland’s right to the property. Antoine’s brother Estalon pre-empted the property in 1874, Sandwell says, and immediately became involved in a quarrel with his brother about it. Antoine eventually ended up in the New Westminster insane asylum, while Estalon took over the whole property and prospered from it.

We will never know just what happened to William Robinson, or why, but the effect of his death (and those of the other two Black men) was to alarm the community—especially the Black settlers.

Several of them left the island, and Louis Stark wrote to Joseph Trutch—now the colonial land agent—advising him that he had moved his claim to a safer site in Ganges. Since the death of Curtis, Stark had been unable to hire anyone to work on his relatively isolated farm.

Stark may even have considered moving off Saltspring altogether. Sylvia recalled Stark’s working a claim on Vancouver Island with a Black man named Overton. (A man named David Overton died in Nanaimo in 1890, aged sixty-eight, but the BC Archives have no record of a pre-emption on Vancouver Island by him. Stark pre-empted land in the Cranberry district, near Nanaimo, in September 1872.)

The evolution of Saltspring society

Political life on Saltspring was rarely as intense as in Victoria. When the overworked settlers did act politically, it was usually to demand something from a colonial government that cared very little about them. Sir James Douglas was slow to appoint a justice of the peace for the island because he thought none of the residents competent to fill the post.

In their first election for an assemblyman, the settlers voted for John Copland, but he lost to J.J. Southgate—perhaps through fraud. John Craven Jones was reportedly suggested as a possible candidate for the House of Assembly, but he never ran.

Saltspring voters seem not to have split along racial lines. In 1868, however, Black voters may well have been responsible for the nongovernmental election of Mifflin Gibbs as the island’s representative to the Yale Convention, which helped frame the terms of British Columbia’s entry into Confederation.

The first elected body on Saltspring was a three-man school board including Abraham Copeland, a Black settler. The board asked repeatedly that John Craven Jones’s teaching be officially recognized, and that he be paid a salary. It pointed out that Jones had a first-class teaching certificate, and that the settlers had “18 children between the ages of 5 and 16 who are destitute of any opportunity of attending day school.” Since Jones was also being sniped at and occasionally beaten up as he made his rounds, the government’s slowness to pay was all the more unforgivable. In 1869, after nearly a decade of unpaid work, Jones finally received an official appointment, and a salary of five hundred dollars a year.

John Jessop, British Columbia’s first superintendent of education, visited Saltspring on a tour of inspection in 1872. He was critical of the time Jones spent “itinerating between the Middle and Northern settlements . . . none of the children are more than three miles from the School-house and the road is improving year by year.” Parents aware of cougars, bears and snipers might have been equally critical of Jessop’s naïveté.

The superintendent was unimpressed with what he saw on his one-day visit to the northern school. Only two girls and a boy, out of seven children in the area, were present. (Sandwell notes that poor attendance was a chronic problem for decades in Saltspring’s schools.) F. Henry Johnson, in his biography of Jessop, quotes from the superintendent’s report: “The boy was working in Latin Grammar, having become such a proficient in English Grammar and Geography that those studies were dropped a year ago and Latin substituted! So the teacher reported. An examination in those branches did not by any means establish the fact of former proficiency.”

Given the nature of such examinations (“What is the usage of that as a Relative Pronoun; what other parts of speech might it be?”), it seems likely that Jessop was judging Jones’s pupils by standards of rote learning. A safer estimate of Jones’s abilities can probably be gained from the fact that he was a well-liked and respected teacher who stayed on the job despite endless hardships. Most BC communities saw rapid turnover in teachers—one settlement had fourteen in five years—who were often detested by children and parents alike.

By the early 1870s, Saltspring was populous enough to warrant some self-government. Victoria issued letters patent for the township of Saltspring Island in 1873. Of the seven councillors elected, two were Black—Jones and Henry W. Robinson, who acted as council clerk. Within a year, however, some settlers were protesting the council’s actions, which they saw as committing taxpayers to needless and expensive projects. On an island where people settled because it was cheap to do so, this was predictable.

Though the controversy was bitter, no one seems to have raised the race issue. The division was between individualistic pioneers who wanted to be left alone and “boosters” trying to develop the community. Sandwell’s study describes a kind of proto-hippie community on Saltspring, much like those that emerged in BC in the 1960s and ’70s: settlers who preferred to get by, not to get rich, and to live their own lives rather than please the bureaucrats in Victoria.

Perhaps the best evidence for Black pioneers’ success on Saltspring Island is that their history became relatively undramatic after the first violent decade. Among White, Indigenous and Polynesian settlers, the Black pioneers became just another group. Most of the original Black settlers would eventually leave, in part from fear of attack, but mostly because Saltspring was not the farming paradise it had first seemed.

As agriculture developed in the Fraser Valley and the Okanagan, farming on Saltspring became only marginally profitable. For economic reasons, then, the children and grandchildren of the Black pioneers moved to Victoria, Vancouver or even back to the United States.

Nevertheless, Saltspring Island has kept its multiracial, multicultural character. In their 2009 book Every Goodbye Ain’t Gone, writer Evelyn C. White and photographer Joanne Bealy offer a portrait of the island with descendants of the original settlers—White, African American, African, Caribbean, Asian and Polynesian—growing up together, marrying one another and bringing up happy children.

The contribution of Saltspring’s pioneers, though sometimes misunderstood or distorted, was a real one. As Sylvia Stark’s daughter Marie Stark Wallace said of them, they were men and women “willing to go into the wilderness with axe and gun only, at their own risk. . . . whose courage and constancy blazed the trail and laid the foundations. . . . they are the uncrowned kings of pioneer days.”