Cooking and Preserving Fish

Cooking

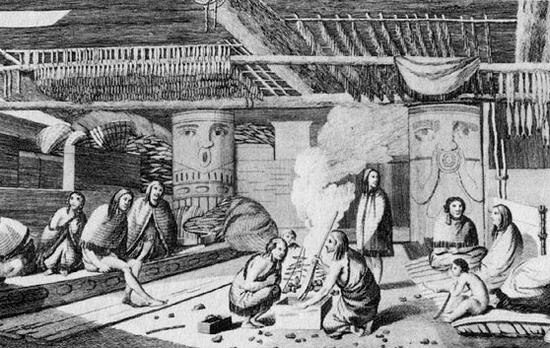

Without any knowledge of pottery, coast Indian peoples boiled, simmered, steamed, baked, toasted and roasted most of their food. Box, basket, earth pit, rock oven, hot ashes, and roasting tongs and sticks, all in conjunction with fire, were the ways used for cooking. Not all peoples used all methods, although boiling, steaming, and roasting were common to all and most generally used, especially for fish.

Pieces of dried fish could be toasted over the fire until hot and crisp. To be boiled, dried fish required soaking overnight. For roasting, the fish had to be freshly caught, and a hot, smokeless bed of coals was needed.

Anyone who attended the annual inter-tribal canoe races of the Coast Salish people will have had the opportunity to taste salmon roasted over an alder fire. Cut into individual steaks, the fish is skewered on a stick of ironwood (Holodiscus discolor), four to a stick. A continuous row of these sticks leans towards the fire, each carefully watched and turned at just the right moment. For many years before his death at the age of 87, Chief Dominick Charlie was in charge of the salmon roast at all the canoe races held on the North Vancouver shore of Burrard Inlet.

While camping on a remote wilderness beach on the west coast of Vancouver Island, and feasting off the fish and intertidal abundance of the environment, we discovered the gourmet flavour of salmon roasted over an alderwood fire. Using cooking tongs and split cedar sticks to hold the split fish open, we let the long slow cooking preserve the juices and the wood fire enhance the flavour. Eaten with wild beach peas growing in profusion near our camp, and sun dried dulse gathered from a small offshore island, this succulent salmon feast ended with a clam shell full of assorted wild berries and a bowl of spruce leaf tea.

On another day at our beach camp we caught a small ling cod and chose to cook it in a steam pit, together with a few clams. We dug a pit, filled it with wood, put rocks on the top and set the wood on fire. When the fire died down we put fresh seaweed on the hot rocks, a layer of large leaves over the seaweed and then the fish pieces and the clams; more leaves and more seaweed until the pit was full. Water was added and the pit was covered over. The flavour of both fish and clams was delicious, and the steam pit had the advantage of not having to be watched; it kept the food hot until we returned from berry picking.

In the Indian village of the coast all cooking was done by the women. They were conversant with many different species of fish, and with a variety of parts of those fish, not just fillets and steaks. When a chief gave a great potlatch it was the women who cooked and prepared the huge quantity of food to feed the many guests who stayed for days, sometimes weeks.

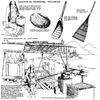

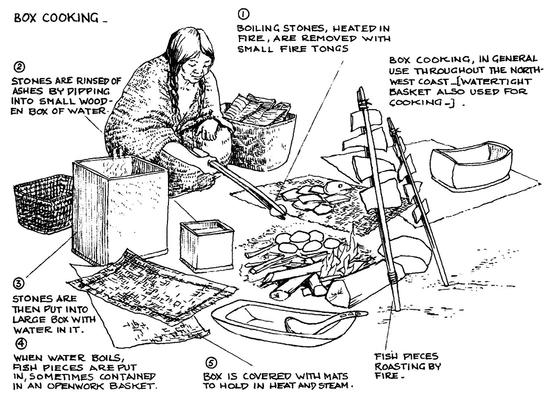

Boiling and cooking was done in the cooking box, or sometimes a waterproof basket, that was set near the fire. Heated rocks, picked up with tongs, were dipped into a small box of water to rinse off the ashes, then put into the bentwood box partially filled with water. When the water came to a boil, the food was added and the lid put on the box. Prolonged cooking or simmering was maintained by replacing the cooled rocks with freshly heated ones. Other ingredients could be added to the box to make stew. When ready, the food was either ladled out, or lifted out with a strainer.

Every part of the salmon was cooked, and even tails, quite meaty on one end, were used. These were held in the tongs and roasted over the fire until they blackened, then removed and set just above the fire to keep warm. The owner of the house could then help himself to a few as a snack when he became hungry. Dried backbones, too, butchered so as to have a lot of meat left on, were broken into pieces and toasted over the fire for snacks.

The rock “oven” was an ancient method of baking fish, and remains of these are found in archaeological excavations, as well as circles of stones indicating where fire hearths once were. At the 1971 excavation of the Katz site, on the bank of the Fraser River downstream from Hope, we found both, together with many fragments of ground slate knives used for butchering fish. Only a stone’s throw away, an elderly Indian woman daily tended her gill net in the river, butchered the fish, and hung it up on a fish rack to dry in the warm winds. It was no coincidence that she was at the same spot on the river as the people who had used the slate knives and rock ovens, the people who had a village there for hundreds of years.

Preserving Fish

There were almost as many ways of butchering and preserving fish as there were of catching them. The various methods differed with the species of fish, the season, the climate of the area, and tribal or local tradition. The result, whatever the method, was dehydration of the fish so that it could be kept for a considerable period of time. It was this skill in preservation that enabled a large population to thrive along the coast, for the ability to catch a great quantity of nutritious food at any one time would have been of no use without the ability to preserve it for a future time of need.

If the salmon run failed or was poor, there could be hunger or even starvation in a village. But if the run was abundant, bad weather could be equally disastrous. In bad weather as much as possible of the butchered fish would be taken into the houses to dry, but the limited space would not allow for the drying of sufficient fish to last the winter.

Improperly dried fish turned mouldy and spoiled, and even well-dried fish was subject to attack by insects unless frequently inspected and carefully watched. Thus the preservation of the catch was as important as the quantity.

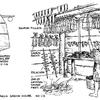

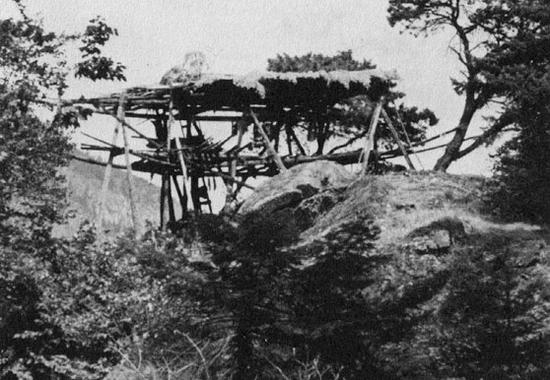

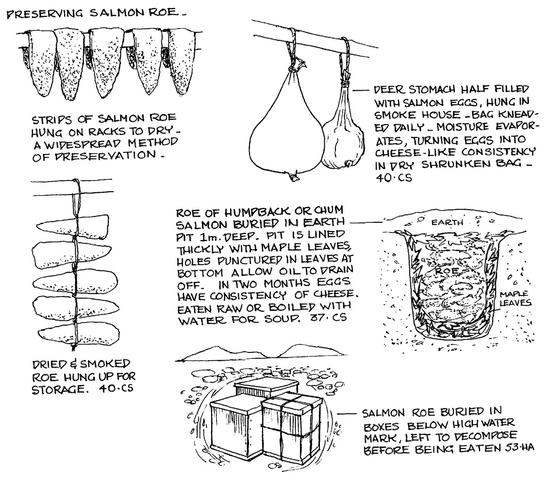

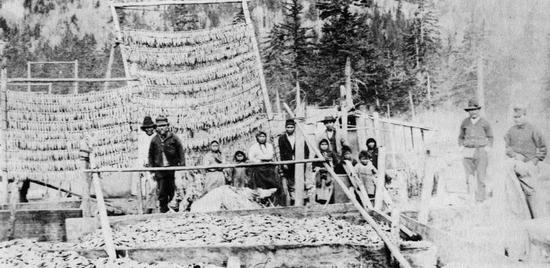

The two basic ways of preserving fish were by sun and wind drying or by drying and smoking. In the drier areas along the Fraser River, where the weather could be relied on with greater certainty, the age-old method was the outdoor drying rack roofed over with planks or branches as protection against direct sunlight and possible showers. Opened flanks of salmon, backbones, roe, and even heads were carefully tended to ensure even drying, with the flesh sliced in a special way to facilitate the process. Large spring salmon caught late in the season, when the weather was unstable, were cut thinner to promote faster drying.

Just beyond Yale on the Fraser River, where hot August winds funneled through the canyon, drying racks were poised high on rocky outcrops. Here salmon hanging from the poles dried in a few days. Layers of the flat dried fish were stacked between branches of green alder boughs to keep them in good condition and away from wasps until they were taken back to the village. The racks are still there and are still used, but as numbers of salmon diminish and government regulations tighten, they are no longer filled to capacity as I have seen them in years past.

Most other coast peoples had to contend with the rain and damp of unpredictable Pacific weather. They relied on drying and smoking to preserve their fish, and enjoyed the added flavour that smoking gave. Smoke houses, some quite large, were a vital part of the fish camp. Built of cedar planks over a sturdy post and beam frame, the building often had a second storey with a notched log ladder for access, and this was sometimes used for storage. Inside, rows of long slender poles held the fish high as the smoke permeated the fish before making its escape through the open hole in the roof and the cracks between the planks. Some smoke houses had a low bench-like rack around the walls where dried salmon were stacked in such a way as to permit air circulation. From pegs in walls hung strips of roe and pairs of backbones, while fish heads (the cheeks were a delicacy) were skewered on sticks for smoking.

Salmon could be half smoked for eating right away; then it was left soft. Fully smoked fish became hard as it was completely dehydrated for storage. Some people pounded the fish frequently during the smoking process in order to keep it soft.

As well as in the smoke house, fish were often dried in the bighouse close to the fire or hanging from poles under the roof where they would be flavoured by the smoke of the fires spiralling up to the smoke hole.

In early June one year when I was canoeing with friends in the Queen Charlottes we paddled into the sheltered mouth of the Ain River, in Masset Inlet. Well constructed cabins straggled along the grassy bank and between the trees, some built on similar lines to the old-style plank houses but having a corrugated iron roof. At the far end of the fish camp an old disused smoke house was leaning under the weight of great age and weathering. Its beams and posts were mostly hand-adzed. Another smoke house, not as old, served the present needs of the fish camp, and looking inside I saw the ashes and charcoal of four fire hearths on the dirt floor, evenly spaced in the four quarters of the interior. The vertical cedar plank walls and the racks were blackened from the smoke of many years.

Rights to fish the Ain River traditionally belong to the Haida of Masset, and many of them still make the long trip by boat (the only way to reach it) to net the salmon that annually migrate up the river to spawn. The fishing season had just ended and the camp was deserted, but in the smoke house the delicious aroma of smoked salmon still lingered.

More recently, I visited another of this band’s fish camps, at the mouth of the Yakoun River on the opposite (south) side of Masset Inlet. Here the cabins perched on the brink of the river bank on both sides, and wooden ladders provided access down the steep bank to the river when the tide was low. Drying racks stood close by the smoke houses and vivid red fillets of sockeye salmon contrasted sharply with the dull grey of the overcast sky. I watched expert hands butchering and processing the fish, and went out with the fishermen to check the nets periodically. Powerful outboard motors had long replaced the tedious process of poling the canoe upriver against the current, but the problem of seals coming into the river to take bites from the fish caught in the nets remained the same.

Salmon from the smoke houses was eventually canned and cooked in a large metal container on an outdoor fire. Now the bentwood boxes of smoked and dried fish of the old days have been replaced with rows of shiny cans stored away in kitchen cupboards. But the love of the salmon is the same, and the pursuit of it brings families back to the fish camps year after year.

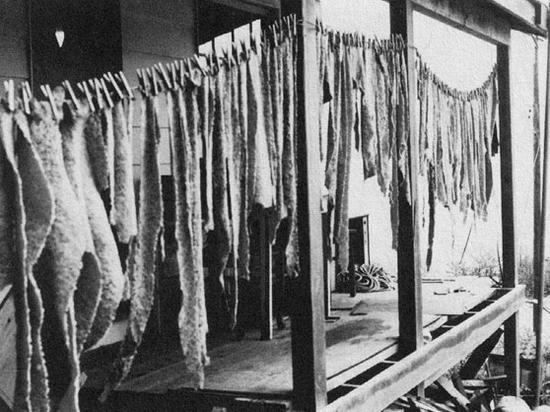

Not having rivers teeming with hordes of salmon as in most areas, the Makah, Haida, and Tlingit were more reliant on halibut for their winter supplies. The flesh of the large fish, sliced as thinly as possible, was draped over the drying rack like pieces of fabric, after much of the moisture was first pressed out with weights. When it had been sufficiently smoked, the white meat turned a golden tan colour. Black cod, also, was dried and smoked for storage, but it did not keep as long as halibut.

Having a good supply of food put away for the winter must have been comforting, but it was not achieved without a great deal of effort by the whole community. During the salmon runs especially, because of the sudden influx of such a huge quantity of fish, long hours of work were required to catch, transport, butcher, clean, fillet, dry, smoke and then finally store away the catch. Men often fished all through the night when the run was at its best, for it was men’s work to catch the fish. They were the skilled harpooners, the spear throwers and the netters; it was men who pounded stakes into river beds to construct traps and weirs, and who hauled heavy rocks to build up the stone dams. While a woman paddled a canoe, a man swept the herring rake through the water and filled the craft to the gunwales with the glittering fish.

But the credit for providing a winter supply of food did not rest solely with the men. All the great catches of fish and all the abundance of food from the sea would have been useless without the skilled hands and hard work of the women. It was the women who laboured long and tediously to clean and butcher the catch. A trap might take a hundred salmon at a time, but the fish had to be cleaned and cut individually, one at a time. It was the women who hung up the butchered fish, tended the drying racks, watched over the fires in the smoke house, turned the fish at the right time, and took it all down when experience told them it was fully cured. Women stacked up the dried flesh, loaded the baskets and boxes, filled the caches, and kept a constant check on the stored food to ensure that it did not spoil.

And when evenings shortened and darker nights turned fall into winter and north winds blew; when the feasting and potlatching began, and when bowls of eulachon oil were set beside dishes of smoked salmon or halibut; or when large feast bowls were brim full of fish soup and the big house was filled with guests and the aroma of good food, then the weeks of work by both men and women—and youngsters too—were rewarded in many different ways.

Dried Herring Spawn

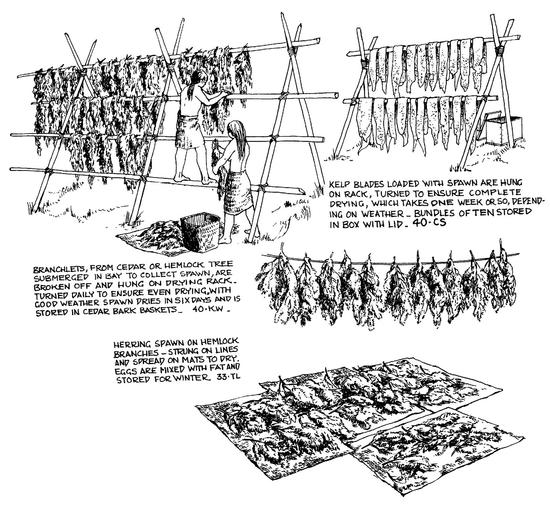

A favourite food of the past, herring spawn is still gathered, dried and enjoyed by many Indian peoples today. I was in the Queen Charlotte Islands in the early spring of 1975, a year that experienced an exceptionally heavy run of herring. Standing on the dock at Skidegate Landing I watched a small boat being rowed in. The craft was laden with piled-up lengths of spawn-covered kelp draped over the seats and in the bow. The young couple in the boat had gone out early to be at the kelp beds at low tide, when it was easier to reach the seaweed.

In the village of Skidegate long lengths of seaweed, creamy amber with spawn, hung from nearly every porch and sun deck; racks and clothes lines in gardens and carports were festooned with it. Some of the kelp was draped over the lines, but much of it hung down full length, held at the top with clothes pins, blowing freely in the breeze. The owner of the large hardware store in Charlotte City said he hadn’t a clothes pin left in the place.

In the old days, spawn-covered branchlets were hung in the sun on racks or lines, or spread out on mats and turned frequently to ensure complete drying all over. In some areas the branches were taken down and the spawn wiped off and scattered on mats to finish drying. Put in a lidded box, the crisp, dried egg masses were stored for winter use.

Spawn-laden kelp was always hung for drying, and the long edible fronds waved in the winds to dry along with the spawn. When hard and brittle they were tied in bundles of ten and put away in a lidded box.

Eulachon Oil

The arrival of the eulachon in spring meant far more than a change of diet, welcome though the fresh fish were. The purpose of catching the fish in such great quantities was for the extraction of their rich and nutritious oil, often referred to as grease.

Villages having hereditary rights to rivers with eulachon runs were able to render large amounts of oil not only for their own consumption but also for trading purposes. Those in villages some distance from such rivers bought temporary rights to fish and render the oil. They encamped by the river until the processing was complete, then returned home with the valuable oil. The Haida, Tlingit and Nootka on Vancouver Island had neither eulachon rivers nor rights to the fish; consequently they, and others, came long distances to trade for the oil with those who had a surplus.

So much sought-after was the oil that it was traded great distances eastward through the mountains to tribes in the interior. Recent research on obsidian trade routes, conducted by British Columbia archaeologist Dr. Roy Carlson, led to a three-man expedition through the coast mountains to the sea. Evidence from their findings proved that when explorer Alexander Mackenzie made his famous journey overland to the Pacific Ocean, he followed one of several ancient trade routes to the coast. Eulachon oil carried along these and other

routes has given rise to the name “grease trails.”

The rendering of the oil was a family or community affair; in early spring, camps on the river banks resembled a massive processing plant. Methods of doing some things varied among the different peoples, but in general the process was much the same.

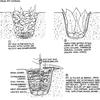

A large pit dug in the ground was filled with eulachon and covered over with logs; the fish were then left to “ripen” for ten days to three weeks, depending on the weather. The warmer the weather, the quicker the disintegration of the flesh that would allow the oil to be released readily. In a large bentwood box, fire-heated rocks were added to water to bring it to a boil, then the rotted fish was put in. As the rocks cooled they were removed, rinsed of fish bits, and returned to the fire for reheating. Fresh hot rocks were then added to maintain simmering, while continual stirring and agitating helped to free the oil from the fish.

After several hours the mixture was allowed to stand. The sediment and liquid sank to the bottom, while the purified oil rose to the top to be skimmed off or ladled out in small boxes with lids.

The canoe that brought in the fish could also become the vessel for rendering the oil. Partly buried in the sand or ground, and supported at the sides with stakes, it served very conveniently as a large container.

With the top oil removed, the residue of mush was scooped up into pliable baskets of woven spruce root. Remaining oil was pressed out with a lever device or by trampling on the baskets in the canoe. Further boiling finally rendered out the very last of the oil.

A three-man canoe filled with eulachon would yield between five and six gallons of oil; a fisherman might catch eight to twelve canoe loads of the fish.

As can be imagined, the odour from processing the oil was excessively strong, almost intolerable for unaccustomed nostrils, and the oil had a flavour to match! The late Chief August Jack Khahtsahlano once declared the oil “good medicine“: when it was two weeks old it had a mild flavour, at one month it was strong; at two months it was “very strong.” The Rev. C. M. Tait, an itinerant minister earlier in this century, recalled an instance when he arrived very late one night at an Indian fishing village:

“… I was immediately ushered into the chief’s house, and his wife began to prepare food for me. A fresh lot of halibut had just come in and she began to cook. Out came her oolichan box, and the big horn spoon, a sort of great ladle made, I think, from the horn of the big-horn sheep. Of course the more grease—they value it—the greater the honour to the guest. I protested that I was unworthy of so much grease, but without avail. To my chagrin she was lavish, and simply showered her esteem on me by smothering the halibut with grease. I never acquired a taste for it. I am without hope that I ever shall.”

Indian peoples relished the flavour and used the oil extensively with their meals. Dried fish, roasted roots, and many other foods were dipped into it, and guests were served the oil in individual bowls, often handsomely carved. Dried berries were mixed with the grease and stored for winter, but even fresh berries were enjoyed with this added ingredient. To eat berries without oil was considered a sign of poverty. Containing iodine and many necessary vitamins, eulachon oil was an important part of the diet.

Stopping off at Hot Springs Island, in the Queen Charlottes, I once had an unexpected opportunity of tasting eulachon oil. A Haida family were staying in their summer cabin close to the springs and graciously offered us the use of the bath house they had built incorporating the hot mineral water—a luxury for us after weeks of boating and beach camping. They also invited us to lunch and for the first time I tried steamed mussels and discovered how delicious they were. On the table was a jar of what, in our ignorance, we thought to be honey with its whitish, semi-crystalline appearance. Fortunately our hostess did not allow us to use it as honey, for it was eulachon oil. She did give us the opportunity of experiencing the taste but, like the good reverend, I am without hope that I could ever get to like it.

Oil rendering was not a process exclusive to the eulachon, although eulachon excelled as a source. The Haida, who were without this oil unless they traded at the Nass River for it, boiled quantities of black cod and skimmed the oil that came to the surface. On the Fraser River, the Coast Salish extracted oil from salmon by putting whole fish in wooden troughs which were left in the sun. When the fish decomposed the oil seeped to the bottom.

The dogfish, with its large, oil-rich liver, was also rendered for its oil content, though not aboriginally. In the early days of sawmilling in Vancouver, Indians caught dogfish off Point Grey, extracted the oil in big kettles on Deadman Island (just inside the present harbour), and sold it to the sawmills. Similarly, the Nootka had a small industry going in the 1880s. They sold the oil to logging outfits, who used it as a lubricant on the timbers over which logs were skidded to bring them out of the woods.

Still manufactured by several families with access and rights to eulachon fishing, the oil continues to find a market up and down the coast. It is now sold by the gallon and the price is high, testifying to its continued demand. In 1968, in the Charlottes, it was $25.00 per gallon; some years later it was selling for $35.00. The price on Vancouver Island in 1976 for oil from Alert Bay reached $50.00 per gallon, but to those who still treasure this important and nutritious food supplement, it is worth it.

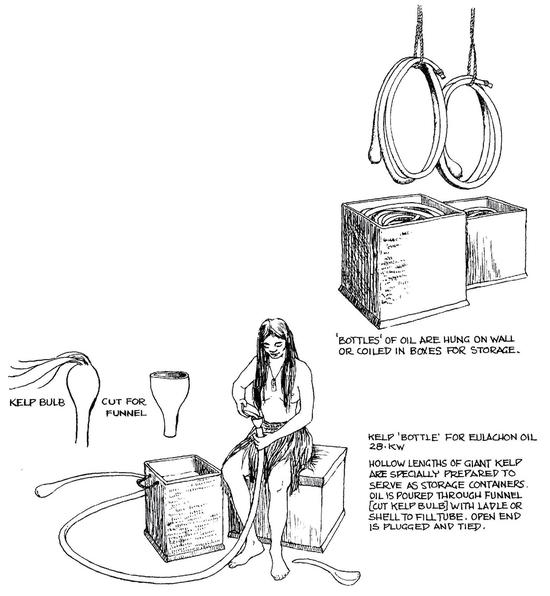

Kelp Bottles for Eulachon Oil

A lightweight storage container for eulachon oil was made from the long kelp stems that grow best in a strong current. These were harvested in the fall on a low tide when they were most accessible. With the leaves of the seaweed cut off, the stipe (stem) was scraped with a section of cockle shell cut to fit its curvature. Dried on a rack over the fire for two days, the stipes were carefully tended to ensure even shrinkage.

To test for airtightness, the sterns were inflated and the open end plugged with a wooden stopper and lashed tightly into place. Those that did not leak air were further dried and bleached before being deflated and stropped around a stake to soften them.

A funnel made by cutting the top off a kelp bulb was used for filling the long stems with eulachon oil. Kelp bottles of oil were coiled up into a box or hung on the wall for storage.

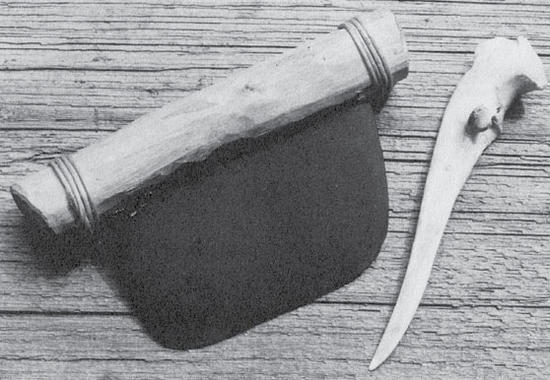

Fish Knives

The implement most used for cutting up fish was a thin-bladed knife made of ground slate, bevelled on the edge and hafted at the top. The wafer-like quality of many of these knives is astounding. Some from the Marpole site in Vancouver, excavated by Dr. Charles Borden, are only two and three millimetres thick, and some, interestingly, bear a strong resemblance to the Eskimo ulu, or woman’s knife. The oldest known ground slate knives date back about 5,000 years; they were used at a site on the Fraser River near Yale.

From the Katz dig, near Hope on the same river, an almost complete ground slate knife was found. So that he could experience the value of this implement, the dig director, Gordon Hanson, used it on one of the salmon an Indian lady living close by had taken in her net. After the fish had been cut open with a heavier stone knife, the ground slate knife easily cut deep scores through the flesh to open it for drying. To see the knife again cutting salmon on the bank of the river brought home the continuity of Indian habitation in the valley.

The Nootka, on the west coast of Vancouver Island, traditionally used only a shell knife for fish, made from the large sea mussel (Mytilus californianus) so abundant on the outer coast. With the edge ground on a sandstone abrader the knife was amazingly sharp. The Nootka felt that the sea shell was a fitting material with which to cut the much respected salmon, and long after metal knives became available to them, they could not bring themselves to put the steel blade into the flesh of the fish. To do so would have been an insult to the salmon.

I was intrigued to find in two museums small copper implements shaped like a mussel shell. There were no data on these, but I speculated that they might represent early attempts to make fish knives from metal. The material used was a break with tradition, but at least the appearance of the shell shape was maintained—perhaps out of respect for the salmon.

Another useful knife was one easily made from a deer’s ulna bone, a lower foreleg bone. The shape of the bone lent itself naturally to edge sharpening, and while it is usually referred to as a herring knife, used for splitting open herring, I feel sure it had many other uses around the house. I made one of these and found it would cut nettle fibre string and cedar bark as well as split herring.

Eventually, when iron and steel began to replace more and more of the natural materials used for tools and implements, the ground slate fish knife fell into disuse. It was replaced with a knife made from part of the blade of a hand saw, though this knife was used the same way and given the traditional shape with the same hafting. Ultimately it too was replaced by the modern, long-bladed knife bought from the store.

In the renewal of Indian people’s interest in their old ways, and in the search to better understand how things were done, the saw blade knife is back at work. Robert Davidson, renowned Haida artist, carver and jewellery maker working in the Lower Fraser Valley, returns to the Queen Charlotte Islands annually at the time of the salmon run to fish and preserve the much loved sockeye. At the fish camp on the Yakoun River I found him butchering the red meat in the old way, using the traditional shaped knife on the triangular wooden cutting block.

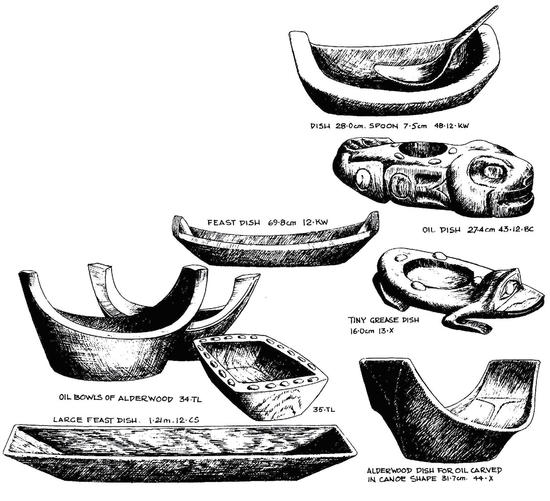

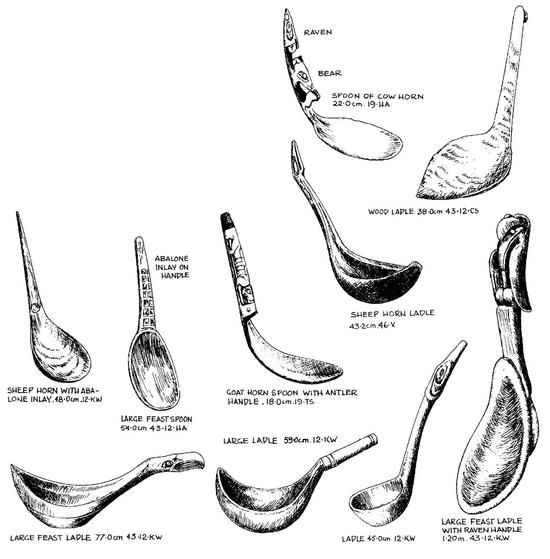

Spoons, Ladles and Bowls

Some of the most superb carvings of the Northwest Coast were to be found among the eating and serving utensils of a household. Artists carved bowls, spoons and ladles with pure flowing lines in simple statement, or elaborately embellished. Family status and wealth were reflected through the splendour of great feast dishes, the elegance of individual bowls for oil and the complex intricacies of goat and sheep horn spoons and ladles. But the care and attention focused on the eating utensils might well have also been a tribute to that vital and life-sustaining creature: the fish.

Etiquette and Feasting

Just as our society requires good table manners and eating habits from those said to be “well brought up,” so did the Indian cultures have standards of mealtime behaviour and etiquette among people of high class.

The seating arrangement was of prime importance, particularly when guests were invited. People were seated according to rank and social status and the highest ranking people received the most desirable portions of the food. Good manners required that small bites be taken with only partially opened mouth, the food be eaten slowly, and the chewing and swallowing done discreetly. It was not good manners to talk about food while eating. Solid food was eaten with the fingers, and water was provided before and after a meal to cleanse the hands, with shredded cedar bark for hand towels.

For special guests and at feasts, the “best dishes” were brought out and used. These would be the beautifully carved feast dishes, the handsome individual oil bowls, often inlaid with operculum, the carved sheep horn ladles and bowls, and goat horn spoons.