The People of the Sea

At the mouth of a river a sleek canoe is being paddled by a thickset youth, his eyes watching the surface of the water, his spear at the ready. Seeing a salmon jump, he at once speaks to it in prayer:

"“Haya! Haya! Come up again, Swimmer, that I may say ‘Haya,’ according to your wishes, for you wish us to say so, when you jump, Swimmer, as you are speaking kindly to me when you jump, Swimmer.”

"

The salmon hears the prayer and jumps again. “Haya! Haya!” And the spear flashes toward the silver swimmer.

On a warm day late in summer, when the stinging nettles have grown tall from moist air and rich earth, a small group of women cut the slender stems that tower over their heads. From the split and dried stalks their experienced hands prepare long fibres, spin the fibres into twine, and knot the twine into fish netting so strong it can lift a load of herring from the water into a canoe.

With gnarled hands an old man pulls a piece of hollow kelp stem from the ashes of a fire. From it he draws a slender stick cut and shaped from a hemlock branch, and deftly bends the steamed wood into a curving U shape. He is making a set of fish hooks for catching halibut.

A baby’s constant crying fills a crowded plank house on the edge of a village, and a young mother soothes her child by rubbing rat fish oil on its small naked body.

Using a piece of rough dog fish skin as sandpaper, a carver smooths the inside of a wooden bowl he has made in the shape of a frog. It is to hold eulachon oil for a coming feast. He inlays the rim with sea-snail opercula, securing them with fish glue.

An old woman tends a smouldering fire as smoke curls its way through the rafters of a smoke house, curing and drying great quantities of butchered fish hanging from the poles. Then she goes outside to the drying racks and checks on the rows of half dried fish.

A man brings his canoe loaded with halibut and black cod through twelve miles of rough water back to the beach of his village. Though hungry and tired, he unfastens, cleans and puts away all his fishing gear before eating a meal.

At one time scenes like these were reflections of everyday life along the thousands of miles of Pacific Northwest Coast and the rivers that flowed to it. The terrain, profuse with islands, channels, inlets and bays, sheltered many hundreds of villages housing many thousands of Indian peoples of several different cultures. They spoke different languages, and many of their beliefs, their ways of doing things, their ceremonies and their design styles differed one from another, but the one thing they all had in common was the sea and their dependency upon it.

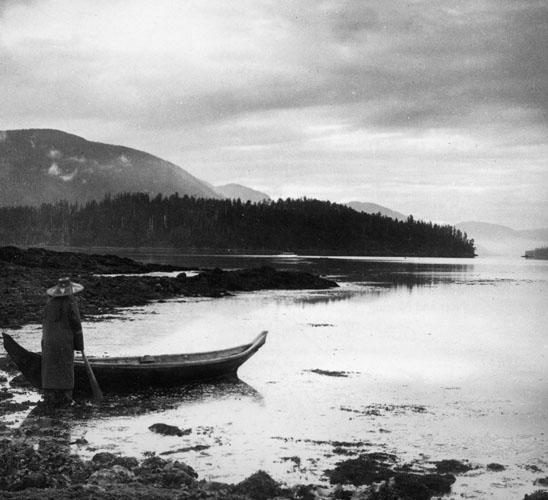

All villages hugged the water’s very edge; all houses faced towards the water. To the Indians of the Northwest Coast, the sea and the rivers were not just a way of life but life itself. In some areas there were inland trails for hunting, berrying, trading and other activities, but the waterways were the main highways. These were traveled swiftly by dugout canoes of various sizes and styles developed to meet different needs. The long, straggling row of canoes on the beach in front of the village was evidence of the people’s marine mobility. The same scene was repeated in villages on those rivers which flowed into the sea.

The people traveled to socialize, to attend a feast in another village, or to trade, exchanging goods they had in plenty for those not available in their area. They traveled to make war, to revenge a wrong, or to capture slaves for a chief’s household; they traveled to hunt sea mammals, to reach a good berrying place, to collect basketry materials or slate for tools. And they traveled to fish.

The beaches of the sea produced an abundance of shellfish, edible invertebrates and seaweeds. The long kelp stems of the rocky coast were made into strong fishing lines and storage bottles for eulachon oil. Sea shells were made into tools, implements, and ornaments. Many myths, songs, dances, and ceremonies were based on some aspect of the sea or the river, its spirits, the underwater world or the characteristics of the fish. Creatures of the sea became family crests or spirit helpers, and were carved into bowls, painted on possessions, tattooed on the body, woven into baskets and everywhere incorporated into the patterns of life.

Indeed, mankind itself was born on the edge of the sea. It was Raven, according to the Haida, alone and lonely in an empty world, who wandered down to the beach. From the wet sand at his feet came a bubble and a small sound. He saw a half buried, partially open clam shell and looked closer, bending his head to listen. He heard a soft sigh and the two halves of the shell began to open. A small face peered out then shyly withdrew again, afraid. Raven called to the face in a whisper and it slowly reappeared, stretched its neck, looked up at him and quickly withdrew again.

Once more Raven whispered, “Come out, come out!” Another sigh came from the shell and another face peered from between the valves. Soon there were more sighing sounds and more small faces until a whole row of them appeared from the edge of the shell. Little arms came out, pushing the clam shell open wider. Unfolding, stretching and emerging, hordes of little people released themselves from the open shell and went off to populate the land. They were the first people, and born of the shore they still lived by the shore.

A part of the vast system of life-support for the sea is the rivers that drain into it; among those of the Northwest Coast are the Stikine, the Nass and the Skeena to the north; centrally the Bella Coola and the Nimpkish; to the south the Squamish and the great Fraser River. Into these and countless other waterways swarmed the teeming millions of fish on the annual migrations, and along these valleys and inlets, and the nearby islands, thousands of people made their homes.

Villagers without nearby access to fishing runs made the often long journey by dugout canoe to reach their traditional fishing grounds. In the spring, the summer or the fall, depending on the locale and species of fish running, entire families moved out from their villages, glad of the change of activity and happy to have the chance of meeting friends and relatives who also gathered at the fishing grounds. They set up temporary camps and spent many weeks by the river, the men catching the fish, the women butchering and preserving them. Preserving the catch ensured a supply of food throughout the winter when the salmon were not readily available and when conditions for catching other fish were not as favorable.

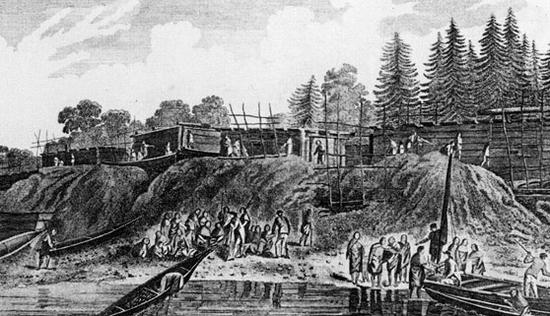

During the establishment of Fort Langley on the Fraser River, July and August entries from an 1827–28 journal (author unknown) make numerous references to the constant flow of canoes heading up the river for the salmon fishing. It names tribes, some from as far afield as Vancouver Island, and describes how the canoes moved two and three abreast lashed with planks between them to form a kind of barge that carried a whole family with its household goods. From mid-July to late August frequent journal entries note “Indians passing up in hundreds”…“Families from the Saanch [sic] village at Point Roberts have been passing in continued succession during the day all bound for the Salmon Fishery”… “Indians in swarms proceeding to the fishery above.”

The September entries kept tabs on the number of canoes returning with their load of dried fish, many of which stopped at the fort to trade some of the catch. “Sept. 22nd, 1828… 150 Cowichans families stopped at the wharf… there are now 345 canoes of Cowichans already passed.” The following day saw “100 canoes” go down the river, the next day “60 more canoes” and the day after “200 canoes of Whooms stopped alongside the wharf, they are on their way to Burrards Canal for the winter.” (This probably refers to Burrard Inlet, where there were winter villages.)

Families owned specific places at the fishing grounds and these were known and respected by others. A man might invite a relative to fish with him, or someone might request permission to use another’s fishing spot, and if he needed the food he was not refused. A good fishing place could even be leased out to someone for payment. The rights and privileges to fishing places were inherited from one generation to the next, or sometimes gained through marriage. Year after year families exercised the rights they had owned for hundreds of years, taking the fish they needed to feed their families and others of the village, to give feasts, to trade, and to keep going through the winter. It is no wonder Indian peoples today consider unjust the laws that deprive them of those long-held rights.

While the five species of salmon were the favorite catch, they did not migrate in such large numbers in the north, so that the Haida and Tlingit were far more dependent on the halibut, a large fish plentiful in that area. Caught in quantity by highly specialized gear, halibut could be preserved well by drying and smoking, and provided good reserves of food for winter.

Eulachon, caught in tremendous quantities in the rivers, were most valued for the rich oil they contained. In addition, the sea provided herring, various species of cod, kelpfish, red snapper, dogfish, flounder, smelt, devil fish (octopus), and many others. The rivers yielded sturgeon, trout, steelhead, and more.

The Northwest Coast Indian was totally adapted to living with the fickle ocean, its inlets, channels and straits and the rivers that flowed to the sea. He knew the ebb and flow of the tides, the currents, the changing winds that turned the water from a gentle ally to a violent, cruel enemy. He understood and respected the sea, its creatures and the entire coastal environment in a way the white man cannot. He loved the coast with a deep reverence, and in return the coast was good to him, providing him with wealth and nourishment for both body and spirit.

Because he was so completely in tune with the ways of the sea and river and all that was in it, the Indian was able to devise many methods for reaping its harvest. Differences in geography, climate, tides, species of fish and variations in culture led to different procedures in catching fish and different ways of making the gear required. But among all people dwelt the deeply inherent tradition of gathering the bounty of sea and river.