Traps and Weirs

Probably the most productive of any of the fishing devices, the traps and weirs allowed large quantities of fish to be taken at a time when the salmon runs were at their peak.

Weirs—fences through which water flowed—were either built right across a shallow river or angled to guide the migrating fish into traps. The traps were either the removable type made with a basketry technique using sticks and lashing, or were structures built into the river bed.

Stone traps were basically wall-like rock alignments built singly or in a series, in a river, at its mouth or in a bay drained at low tide. These would either function as a trap or funnel the fish towards the mouth of a trap.

Two basic principles were responsible for the success of almost all the weirs and traps. One was the relentless urge of the salmon to make its way upstream to its spawning grounds despite all obstacles; the other was governed by the ebb and flow of the tide. Many species of fish drift shoreward on the incoming tide, and recede again to deep water on the ebb tide. This especially applied to salmon congregated at the mouth of a river as they awaited melting snows or heavy rain to swell the creek. They swam over the traps on the flood tide and became trapped or stranded on the ebb.

Variations in trap devices depended on the species of fish, the type of environment, the building materials available, and the cultural background of the people. The wide variety of traps seems to underline the Indian’s keen observation of marine life, and reflect his ingenuity in harvesting the resources of the sea.

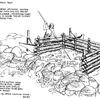

Fish Weirs

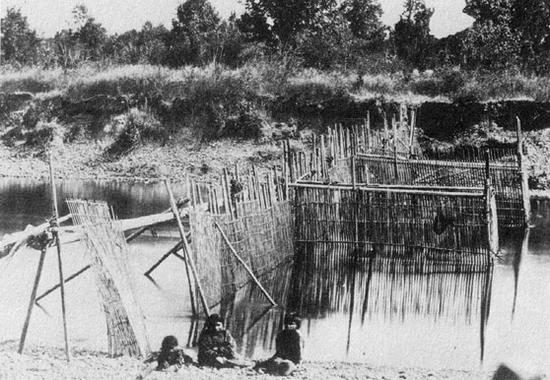

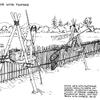

Weirs were built in shallow estuaries, rivers and streams, either to block the upstream passage of salmon or to guide the fish into a trap—or towards the fisherman with waiting spear. Some fence weirs consisted of convenient-sized latticework sections lashed to the upstream side of a sturdy framework in the river. The lattice was put up for the fishing season and removed afterwards. The framework remained in the river all year and was repaired as necessary. Fir branches, vine maple saplings or other material could also form the fence.

Ownership rights to traps and weirs varied among the different cultures and bands, but usually a large weir across a major salmon river was owned by the whole village. Building the weir was a community effort—its very size made co-operation an advantage—and everyone shared in the catch. However, a weir across a small stream could be privately owned by a person of wealth or high rank. He would fish from it at night, when the run was at its best, and allow others to use it by day.

Downstream villagers owning weirs had first advantage in harvesting the run. When they had sufficient salmon, sections of the weir were removed to allow the fish to continue upriver, where they would encounter the weir of the next village. It is said that if the downstream people were tardy in opening the weir, their angry neighbours might launch a massive log into the fast flowing waters and smash it open.

It is still possible to find, in a stream or mud bank, or on the beach at the mouth of a stream, the remnants of a long since abandoned weir. Weather-worn stubs of wooden stakes stand in mute rows showing where the weir had once been. The truncated posts, continuing to defy years of spring flood and winter storm, testify to the strength of arms that once wielded a heavy piledriver to pound them into the river bed.

At the mouth of the Little Qualicum River, on the east coast of Vancouver Island, can be seen the posts that once were a part of a weir, and on the beach a two-metre-long post with steeply sharpened point lies partly buried, upended, in the gravel. Upriver is a modern government fish hatchery with artificial spawning grounds. Ten miles to the north, another river also holds the remnants of a fence weir on a beach that is now a trailer park and campsite owned and operated by the Qualicum Indian Band. The rivers have seen changes!

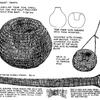

Basket Traps

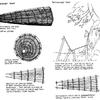

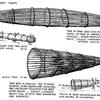

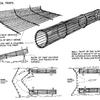

Most basket traps worked in conjunction with a weir or blockade of some kind. Two converging weirs formed a V shape that funneled the migrating fish into the trap. Once inside, the fish became confused and were unable to find the small opening again to escape. Some traps were made very long and narrow so that the fish were unable to turn around to go back downstream in search of another route.

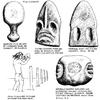

The Haida had names for their fish traps, and the Tlingit attached carved figures to the tops of the posts used in the structures. These beautifully wrought figures may have had special powers to attract the fish, or they may have been to indicate ownership.

John Jewitt’s narrative describes a large Nootka trap (which he calls a pot) and the method of its use:

“A pot of twenty feet in length, and from four to five feet in diameter at the mouth, is formed of a great number of pine splinters,3 which are strongly secured, an inch and a half from each other, by means of hoops made of flexible twigs, and placed about eight inches apart. At the end it tapers almost to a point, near which is a small wicker door for the purpose of taking out the fish. This pot or waer [sic] is placed at the foot of a fall or rapid, where the water is not very deep, and the fish, driven from above with long poles, are intercepted and caught in the waer, from whence they are taken into the canoes. In this manner I have seen more than seven hundred salmon caught in the space of fifteen minutes. I have also sometimes known a few striped bass taken in this manner, but rarely.”

Unfortunately very few of the various kinds of traps remain today. Large and cumbersome, they were not items for collection as were carvings and art objects, and so they eventually disintegrated outdoors. Traps can sometimes be spotted in the background of old photographs taken in more remote villages. Their construction was frequently complex, and most were made with the precision, care and fine finishing so often found in utilitarian items of the coast people.

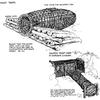

Stone Fish Traps

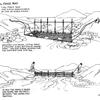

Stone traps were widespread along the whole coast, with the Kwagiutl people making the most extensive use of this effective method of catching fish. In their central coastal area, almost every creek or stream contained some kind of stone trap. Many and often elaborate were the stone-walled structures that relied on “tidal drift” for their success.

Salmon often congregate at the mouth of a stream or creek so that spring runoff or late summer rains may swell the river and make it deep enough for their passage upstream. As the tide rose, the waiting fish drifted shoreward with the flow of the water, swimming over the tops of the traps. As the tide receded they became trapped behind the stone walls, unable to retreat to deeper water.

So successful was this system that frequently a whole series of stone traps was built at one river mouth. Boulders reached a fair size, and the supply was not always close at hand. The large amount of labour involved in moving so many tons of rock into place, and the quantity of fish they would catch, suggest joint ownership and use by a whole village or groups of people. Smaller, single stone traps in suitable places would catch shiners and other small fish for bait.

An elderly and knowledgeable man of the Qualicum Band, Alfred Recalma, told me that there were once so many salmon in the sea at migration time that the traps did not have to be at the mouth of the river; traps along the beach anywhere in the vicinity would catch fish. “The salmon would go up the stream packed together so tight you’d swear there wasn’t room for one more fish,” he said. He blamed logging and the destruction of the watershed for the present-day lack of salmon. Heavy rains pour down the denuded mountain sides and swell the creeks to rushing torrents that sweep away the fertilized salmon eggs.

It is still possible to spot the remains of some of the stone fish traps in bays and inlets, even though many years of tidal action have torn apart walls that once stood much higher. On Mitelnatch Island (south of Cortes Island in Johnstone Strait), in a large bay drained by the outgoing tide, is a fairly obvious V-shaped rock alignment. This is pointed out by a sign put up by the park naturalist on the island, and can be seen at low tide. Less obvious, though, is a series of small, half-circle rock wall remains, also within the bay. Their demarcation is helped by the fact that the oysters now growing there are concentrated on the outer side of the traps, but are sparse on the inner side. Often no more than one boulder high, the rocks of these old stone traps are usually larger than others in the immediate area, and fairly evenly placed in a straight or curved line.

Remains of stone fish traps are evident in Deep Bay on Vancouver Island, and are best seen when the tide is just high enough to allow the lines of the large boulders to appear above the water. Camping at Bajo Point, north of Friendly Cove on the outer west coast of the island, I found a large bay with the tide out and the remains of a series of small stone traps. Near our beach camp was the site of an ancient Indian village. Relatively young spruce trees marked out the rectangular areas where house floors had once been, each outlined by high mounds of earth now tall with wet grass. The rotted bow of a small dugout canoe, moss covered, silent, lay at the edge of the forest within sound of the sea.

The Herring Spawn Harvest

Just as important as catching the herring was harvesting the eggs (spawn) of that fish, a delicacy much enjoyed by the coastal peoples of all areas.

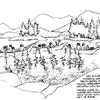

Knowing that the herring run would start in early spring (March), and that the fish would congregate in certain bays and coves with quiet water to deposit their eggs on seaweed, the resourceful fisherman made use of this annual occurrence for his own benefit by careful manipulation.

Prior to the run he set out branches and other material in selected places, and the obliging herring took advantage of the ample supply of substance upon which to spawn. The fisherman, returning a few days later, carefully lifted the heavily laden branches out of the water, piled them in his canoe and returned home to the village.

Spawn-covered seaweed growing naturally was collected also, but the pre-set material was easier to harvest.

__________

3. This wood was probably cedar.