Foreword

For many years Northwest Coast cultures have exerted a magic appeal to layman and specialist alike. We have been swept off our feet by the potlatch, dazzled by dance and sculpture, lured into searching out the rules and meanings of mythology and art. Because there is such richness in accounts of these cultures, we have been easily distracted from examining workaday routines of daily living. Technology has been neglected. Hilary Stewart’s work on fishing is a welcome contribution that will do much to achieve a more balanced understanding of Northwest Coast life.

Technology is fundamental to all cultures, although we sometimes forget this in the face of such natural abundance as characterizes the Northwest. The coast was home for a variety of land and sea mammals, great flocks of waterfowl, and above all, teeming hordes of fish. These were the foundations upon which Northwest Coast cultures were built. But nowhere were riches of nature always abundant or entirely free for the taking. Some of them, on the contrary, were exceptionally hard to get at, as you will see. It was technology, plus the knowledge of its application, which provided the vital links—means for tapping the resources.

What we see revealed in this book is an incredibly varied and highly refined assemblage of tools, techniques and knowledge, the culmination of thousands of years of evolutionary development. These tools and techniques were not imported ready made, nor did they suddenly spring into being. They developed slowly and painstakingly as more effective variations were invented or introduced and applied to achieve more rewarding ends. The final result adds up to one of the most elaborate and productive fishing technologies achieved by any non-industrial society.

Out of the total range of technology, that is the arts and industries of material things, Hilary Stewart has chosen to tell us about fishing. Taken thus, her topic cuts across other categories conventionally used when dealing with material culture. It touches upon the work of men and women, upon things made of stone, wood, and the full range of materials available, but it doesn’t attempt to cover such categories. Appropriately it sticks to fishing and the use of fish, themes at the heart of Northwest Coast cultures.

The artistry of Hilary Stewart’s work is undeniable, but I take that as an added bonus. The meat and substance reside in its descriptive accuracy. Each of the illustrations of artifacts was made from an actual specimen and identifying information is provided. Illustrations of the working use of various devices could not, for the most part, be made from actual observation, and so they are necessarily reconstructions of how it was. But in this the author has used every clue available—descriptions by anthropologists, explorers and Indian informants, information from old photographs, and her own experience.

It is in this last respect that Hilary Stewart has her own unique strength. Artistry and descriptive accuracy are enhanced by her practical ability. Refusing to be mystified by deficient descriptions of long forgotten processes, or to be stymied by absence of data she has set about experiencing the “hows” of doing, by teaching herself. I have before me on my desk a three-foot length of twisted cedar bark twine. It’s smooth, shiny and strong—just the sort of thing to use for cod-line, just the sort of material made in great skeins by Northwest Coast women for just that purpose. Hilary Stewart made it from red cedar bark, split, dried, softened, then twisted on her thigh, as she describes in the book—in order to “see how it was done.” She has also made nettle fibre twine, kelp line, several styles of fish hooks and a host of other objects. All of them are workable and tested.

It is such concern for detail and process, above all else, which marks this book apart. Drawings of the application of hooks, nets and the like are meant to show how the objects worked, and the drawings do more, in this respect, than any photograph or description could hope to do. One finds the working of such familiar things as halibut hooks and harpoons more clearly shown here than in any other available work, and we find here, for the first time, understandable illustrations of such nearly forgotten devices as the Salish reef nets, trawl nets, sturgeon harpoons and how they were actually used.

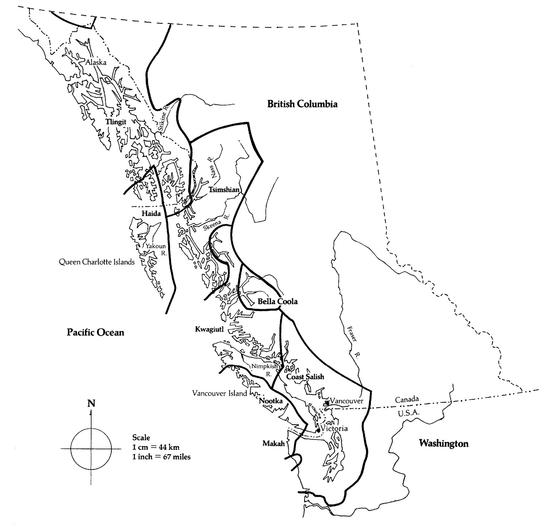

There are, of course, questions which the work does not answer. It is not meant to be a definitive study nor a book for scientists, although they will be informed by it. The Northwest Coast culture area extended from Yakutat Bay in Alaska to Northern California. This book looks at the cultures ranging from Alaska south to Washington. The distribution and frequency of use of artifacts from tribe to tribe is not discussed. Rather, the coastal area is treated as a whole. One must not conclude however that every device or process was equally popular with all the tribes. The author has been honest and practical in the face of the considerable difficulty of sorting out tribal styles and tendencies. She has identified each piece and each process, as best she can, with recorded occurrences. When she tells us that a particular hook was made, or a specific fishing process was used, by a particular tribe, we may depend upon her accuracy. Hilary Stewart tells us what she knows, she does not jump to conclusions or generalize. Readers will be well advised to follow her example.

Finally, it should be made clear at the outset that this book is more than a bare account of the technology of fishing. It is about fish and fishing in the total lives of Northwest Coast people, and that is as it should be. Indians did not separate material and spiritual realms of experience as we tend to do. Fish were holy. Fishing was a connection between humans and the spirit world, never simply a matter of creating tools out of wood and bone, then putting them to work.

Fittingly, this book opens with a myth and concludes with Indian prayers and poetry. In between are “practical” considerations. But separateness of these parts is an illusion. The reality of fishing, for the Indians, was in the whole. We will gain in our understanding of the Indians’ world, and of our own, if we follow Hilary Stewart’s lead and attempt to see the interdependence of myth, tool and prayer. In such unity resides the genius of Northwest Coast culture.

Michael Kew

Associate Prof. of Anthropology

Department of Anthropology and Sociology

University of British Columbia