Spears and Harpoons

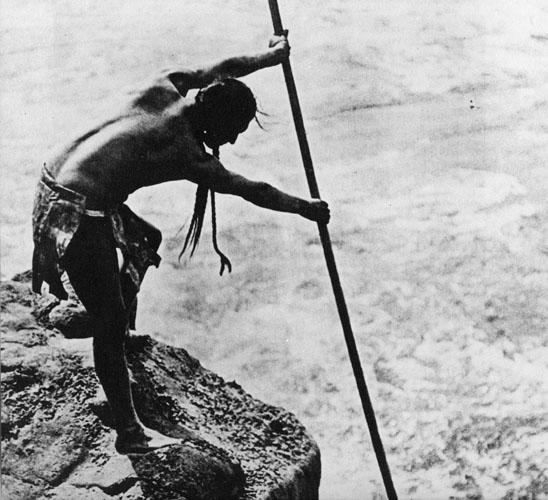

Thrusting his harpoon with just enough power to impale the fish, but not too much to break the gear if he should miss, a man learned to judge the depth of water and the speed of the swimming fish, allowing for light refraction at the same time. Referring to the skill and success of this type of salmon fishing, John Jewitt comments:

“Such is the immense quantity of these fish, and they are taken with such facility, that I have known upwards of twenty five hundred brought into Maquinna’s house at once; and at one of their great feasts, have seen one hundred or more cooked in one of their largest tubs.

“I used frequently to go out with Maquinna upon these fishing parties, and was always sure to receive a handsome present of salmon, which I had the privilege of calling mine; I also went with him several times in a canoe, to strike the salmon, which I have attempted to do myself, but could never succeed, it requiring a degree of adroitness that I did not possess.”

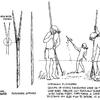

The implement Maquinna used to “strike the salmon” was probably a harpoon. The difference between the spear and harpoon lay in the manner of its use and the nature of the head of the weapon. The spear point was firmly fixed to the end of the shaft, which was thrust at the prey and remained in the fisherman’s hands. The harpoon head became detached from the prong or foreshaft when it struck the fish. It was tethered to the shaft by the lanyard. Some harpoons combined two and even three heads on separate prongs. A throwing harpoon had a finger grip at the butt end from which the shaft was propelled towards the fish, and it was afterwards hauled back in by the attached retrieving line.

While a large, struggling fish impaled on a fixed spear point could break the shaft or point, or free itself by thrashing about, the detachable harpoon head allowed the fish to move in the water without putting direct strain on the gear, while its struggles embedded the barbs well into the flesh.

The harpooning of salmon was generally limited to rivers and streams with clear water, but it was also practicable in bays and inlets, especially where the fish congregated prior to ascending the rivers. If a stream was not navigable by canoe, the fisherman walked up it or along its banks finding suitable places to fish.

So specialized was the art of fishing by harpoon that different types of harpoons were devised for different river conditions. Among the Nootka, for instance, there was a harpoon made for use in a small stream, a river with deep pools in it, a shallow river with rapids, and a wide expanse of river water.

The spear seems to have had its best use with the smaller species of salmon which were close at hand and readily available: for example, at a trap or dam where they were concentrated and could quickly be flipped onto the bank or into the canoe.

An efficient spear for salmon and cod was the leister spear with its reverse-angle barbs that held a fish very firmly. Used with a downward, vertical thrust, the leister was effective in taking salmon lurking beneath a log jam in a river, and was sometimes employed in conjunction with the cod lure. Another specialized spear was for flounder. This had two wooden prongs with tips sharpened to a point, probably to pierce right through the flat fish as it lay half hidden in the sand.

The spear for dragging the tenacious octopus from its den had a reverse barb a short distance from the long point. Chief Charles Jones described for me the catching of the “devil fish.” The long point was pushed into the hunched-up mass of octopus; the barb prevented it from slipping out. By maintaining strong and steady pull on the spear, the fisherman eventually forced the creature to let go its hold. Devil fish was extensively used for bait.

Harpoon and spear shafts were frequently of cedar so as to be lightweight. Strong, durable cherry bark was used for lashing on prongs of a tougher, often springy wood: yew, ironwood, or service berry wood.

Sturgeon Fishing

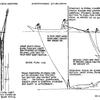

Probably the largest of the fish caught by the coast Indians was the sturgeon, a long-lived freshwater fish that can grow to about six metres (20 feet), and range in weight up to 812 kilos (1,800 pounds). While the sturgeon inhabits the major rivers of the Northwest Coast, the Coast Salish people were the great pursuers of this fish.

The sturgeon, sluggish in winter, lay in deeper water during this time and was not difficult to locate by probing with a two-pronged harpoon with an extended shaft. In the early summer the sturgeon came in to shallower water to spawn, and from April through summer could be taken in the sloughs by fence weir, set net, trawl net and harpoon. Harpoons, the same ones used for seal and porpoise with a trident butt, were used in the daytime on low tides. At night, on any tide, a fish swimming about 2.4 metres (8 feet) deep could be seen well ahead by its phosphorescence, and became an easy target.

A large sturgeon, struck with a harpoon, would take off into deeper water, speedily towing the canoe behind it. The late Chief August Jack Khahtsahlano (born 1887 in Vancouver) once described how a heavy stone on a cedar bark rope would be dropped from the stern of the canoe to help slow down and steady the erratic craft being powered by a captive sturgeon. When eventually the fish tired and sank to the bottom, the line went vertically down—a signal to the fishermen to bring it to the surface. With sufficient lines embedded in the flesh, the fish was hauled up and clubbed on the side of the head.

In a well practised manoeuvre the canoe was then tipped, the sturgeon rolled in over the gunwale, and the water bailed out. Sometimes an outrigger was made to steady the canoe for hauling in a large fish. A pole, with a block of wood at one end, was put across the canoe and lashed to the thwart. Another method of getting the catch home was to simply reverse the fish-towing-the-canoe procedure and have the canoe tow the fish.

The 1827 journal of Fort Langley, on the Fraser River, has a July 21 entry reading:

“We procured a small supply of fresh sturgeon from the Indians today. These fish are as large as those of the Columbia, and are killed in this River with Spears fifty feet in length, having a fork at the end, Barbed occasionally with iron, but oftener with a piece of shell. When the fish is struck, the barbs having a cord, attached to their middle, and held at the end of the Spear, are drawn from their socket and remain in the fish across the wound, til it is drawn up and killed.”

On August 2 the fort traded “two hundredweight of sturgeon” and at a later date “Bought a sturgeon from the Cowichans—weight 400 lbs. the guts out.”

Another eye witness to sturgeon fishing was Sir Arthur Birch, Colonial Secretary at Government House in New Westminster. In a letter to his brother John, dated 7 May 1864, he writes: “I have got a very nice little Wooden Office & my room is charming now though I fear very cold in the winter. It is close onto the Fraser & the balcony & veranda over hang the water. All the Indians now fishing and it is great fun to watch them spearing Sturgeon which here run to the enormous size of 500 & 600 lbs. The Indians drift down with the stream perhaps 30 canoes abreast with their long poles with spear attached kept within about a foot of the bottom of the River. When they feel a fish lying they raise the spear and thrust it at the fish seldom missing. The barb of the spear immediately disconnects from the pole but remains attached to a rope & you see sometimes 2 or 3 canoes being carried off at the same time down river at any pace by these huge fish.”

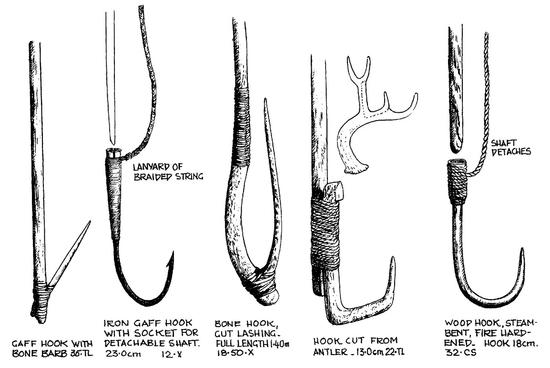

Gaff Hooks

Another method of taking fish, mostly salmon, was by gaff hook. Working from a platform built at an eddy or by rapids, or standing in his canoe, the fisherman quickly jerked the hook upward to impale the fish.

At night or in murky water, the feel of the fish brushing against the hook was the signal for him to strike. A gaff with a detachable hook prevented a struggling salmon from breaking the shaft or tearing itself free.

When the run of salmon was heavy, the fisherman stood on the river bank or in his canoe, and used the gaff with a quick raking motion along the bottom. He also used it at fish traps and weirs to haul out the catch.

Gaff hooks of iron, introduced through trading, eventually replaced those of wood, bone and antler. The metal hooks came fitted with a short handle designed for the white man’s way of using it, but the Indian replaced it with a long shaft to suit his own needs. It is legal for Indian people to gaff salmon and many of them still pursue this practice today.

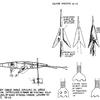

The Herring Rake

Today fishermen complain that herring runs are depleted by overfishing. Once Indians went out in canoes to meet herring that schooled in uncountable numbers. So thick were the fish that they were easily harvested by running a rake through the water to impale them. It was a method of fishing used extensively along the coast, and a single village might have ten or fifteen people on herring rakes gathering up the fish.

For bone barbs, splinters from the leg bone of deer were made by hammering the bone lightly until it began to crack. The crack was followed up until it split, and the splinters then shaped and sharpened on both ends by using a sandstone abrader. With the shaft set sideways between pairs of stakes in the ground, holes were drilled along the edge and the barbs driven in with a yew hammer, or set in with spruce gum.

For wooden barbs, sharpened points of ironwood were driven through the cedar shaft with a hammer so that they protruded on the opposite side in much the same way that nails would.

One account of making a Kwagiutl rake describes the barbs as being “three finger widths long and two finger widths apart,” but a rake I looked at in the B.C. Provincial Museum had barbs more closely spaced, about 1.5 centimetres (⅝ inch) apart. This more closely fits a Nootka rake described by Jewitt:

“A stick of about 7 feet long, by 2 inches broad, and a half an inch thick… formed from some hard wood, one side of which is set with sharp teeth made from whalebone, at about half an inch apart.”

To strengthen and waterproof it, the rake was smoked over a fire for four days, with tallow rubbed in each morning to make the soot from the fire adhere as waterproofing.

Early March brought the herring run and with it the eagles, the gulls, the seals and all the creatures eager for a share of the easily caught fish that would run in such abundance for about twenty days. The best time for herring raking was between sunrise and sunset, when the fish moved up off the bottom. When the fisherman and his wife reached the herring grounds in their canoe, she sat in the bow facing the stern and he sat in the stern facing the same way.

Observing the herring rake in action Jewitt declared:

“It is astonishing to see how many are caught by those dextrous at this kind of fishing, as they seldom fail, when shoals are numerous, of taking as many as ten or twelve at a stroke, and in a very short time will fill a canoe with them.”

In addition to herring, the rake was used with equal success in catching smelt. Sir Arthur Birch, who watched sturgeon fishing from his Government House office window, did more than merely observe the use of the rake. In a letter to England he wrote:

“I took a canoe from below my window and paddling with a rake had in about an hour 600 smelts in the bottom of the canoe. The rake is so—[he made a sketch] about 8 ft. long, you sit right forward and use the rake as a paddle bringing it behind you into the boat each stroke sometimes I would bring up 9 or 10 at a stroke very large smelts and delicious eating.”