Nets and Netting

Indians today still use fishing nets in many ways, but the spun nettle, cedar (and occasionally hemp) fibres of the coast have been replaced by nylon net, while the carved wooden netting needle is now of moulded plastic.

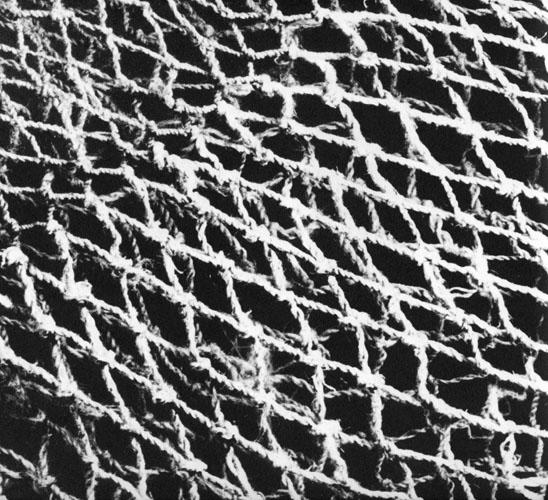

As with fish hooks, spears and harpoons, coastal Indians devised a great many different styles of nets for the taking of fish. A material much used was the well-known stinging nettle (Urtica lyallii) that grew tall in the rich soil of forest clearing or river bank. In an amazing evolution of plant knowledge, the Indians discovered that one part of a plant as formidable as the nettle could be cut, split, dried, peeled, beaten, shredded and spun into a fine two-strand twine of exceptional strength. Interestingly, the preparation and manufacture of nettle fibre into thread was known in early European times and it was considered to be stronger than flax. In fact the word “net” is derived from “nettle.”

On the Northwest Coast, nettles were gathered in late summer or early fall when they were mature, the fat, hollow stems towering over a person’s head. With the leaves stripped off, the stalks were split before being dried. One account of the fibre preparation says that the splitting was done with the thumbnail. I tried it in my experiments in making nettle twine, and although it worked well I found after a while the need to resort to a tool. A bone herring knife, shaped from a deer ulna, made a fine substitute, running smoothly and easily up the stem to split it.

It was the nettle’s cortical “bark” and not the woody inner part that produced fibres. After this was peeled off it was beaten and then cleaned of its outer covering by drawing the lengths of fibre over a section of bone (bear rib) held between thumb and little finger, the other fingers pressing the fibres against the bone.

Long, fine fibres, clean and separated, were the result of much labouring, and these were spun into a two-strand twine by using a spindle, or rolling the fibres on the naked thigh with the palm of the hand. Finding that I was not at all proficient at using the spindle I had made, I tried out the other method, and with blue jeans around ankles eventually came up with a few metres (about four yards) of reasonably good nettle twine. It was then I understood and appreciated the time involved and the skill required to gather, prepare and spin sufficient of the fibre to make a net.

The bark of willow saplings (Salix hookeriana) was spun into two-ply twine for reef nets by some of the southern Coast Salish, while up the Fraser Valley the prepared fibre of a plant now known as Indian Hemp (Apocynum cannibinum) was utilized for netting. The ubiquitous inner cedar bark was also often used for netting.

Net making by hand is another ancient skill still practised in many parts of the world. The size of the mesh must differ according to the species of fish to be caught, and to ensure uniformity of any one size a mesh gauge was usually employed. I was fascinated to watch a young native boy in Hawaii sitting on the deck of his fish boat making a net with agile fingers. The tip of the conical net was fastened to the stay above him, and he worked around the edge as it hung down, adding to the number of meshes every few rows. He measured and knotted several meshes around the gauge before taking them off, thus minimizing labour. The same technique was used by the coast Indians.

Many of the nets on the coast were attached to a hoop or frame of some sort. These served to dip out or scoop up the fish massed in migratory schools or congregated in a trap or dam. Hoops were often of bent vine maple (Acer circinatum) with the net lashed around the rim. I have found that a slender fresh length of vine maple will bend into the hoop shape without steaming.

Pausing on a river raft trip down waterways of the interior of British Columbia one year, I with my companions pulled into the bank on a remote part of the Fraser River. On the other side of a ridge an Indian family had set up their annual fish camp and I visited with them a while. Fish hung on racks above a smoking fire tended by an older woman; tents, bedding, pots and pans, food and an array of belongings indicated a fairly lengthy stay. Every year around this time—it was August—they came to this spot on the river for a few weeks.

For generations their families had been coming, the husband standing on the end of a rocky point jutting into the river, sweeping his dip net downstream with the current, the wife butchering and smoking the fish that would see them through the winter. Children played nearby. I watched the man on the point of rock repeatedly dipping in and taking out the net in a slow steady rhythm, over and over again, hoping for a catch. When a salmon on its upstream journey became caught in the net being swept downstream, it was quickly lifted out and put into a low stone wall enclosure built up of loose rocks. I noticed that the fisherman’s dip net was not nylon but chicken wire! This material was obviously heavy, but he explained its advantage: the salmon would not get entangled and so could be emptied out more easily and quickly.

The fish were few and far between, partly because it was too early in the afternoon (the fishing is better when the sun is off the water; then the salmon rise nearer the surface) but also because there were fewer fish going up the river now. Not as in the old days, he told me, when there were lots of fish and no government regulations. There were plenty of fish in those days and you got one, sometimes two, with every dip of the net. You caught more fish than you needed and you shared it with others in the village, with old people who could no longer go to the fish camps.

Many of the older people are so accustomed to the dried, smoked fish that they can eat little else in the way of protein, and having to do without it creates a real hardship for them.

We ran into similar complaints about the diminishing salmon runs much farther down the river, near Yale, where for countless generations the people have come to their hereditary fishing grounds on the Fraser River. Evidence from an archaeological site on the other side of the river (Site number DjRi-3) dates its occupation back to 9,000 years ago, and in all probability the people then were down at the river for the very same reason: the catching of salmon.

Fishermen here set out gill nets in the quiet backwaters, where the salmon pause to rest in their upriver migrations. In the summer, nets with their wooden floats bobbing on the water can still be seen not far from the highway. In some places a long pole, one end anchored on the rocky bank, holds the net out into the muddy, silt-laden river.

It was early morning. We had set our sleeping bags on a ledge high above the river the night before. Waking to the spectacular sight of shafts of sunlight stabbing diagonally into the canyon through mist clouds on mountain tops, I peered over the rocky ledge to the river below. Two men were striding over the rocks towards a quiet bay with a net stretched across it, and I watched in anticipation. They hauled in the long net by its rope and there, hanging in the net caught behind the gills, was a solitary salmon.

Later I walked along a path to another net and talked with a woman who said that new government regulations had cut down on the number of days a week they were allowed to have their nets out, and now it was hardly worth coming to the fish camps, spending so much time, to catch so few fish. Each year fewer people were spending less time at the camps.

I recalled visiting this same area 14 years before when the river banks were alive with families busily catching, butchering and drying salmon, stacking it between branches of alder to keep it from wasps. Drying racks high on rocky pinnacles were loaded with the bright red sockeye, and warm winds blowing down the canyon worked the miracle of preservation the way it had always done.

But there were a lot fewer fish now, and the blame was tossed in various directions: too many salmon being taken on the high seas, too much commercial fishing at the mouth of the river, pollution of the river by industrial waste.

The following spring, by arrangement with the Masset Band Council, I was at a fish camp at the mouth of the Yakoun River, at the end of Masset Inlet on the Queen Charlotte Islands. The water was shallow, especially when the tide was out, and gill nets were stretched right across one arm of the river. Neat one-room cabins, drying racks and smoke houses dotted the bank on both sides. The falling tide left small boats sitting on mud banks the way canoes might have once been. An eagle circled the gray sky and raven cries brought to mind the myths and legends of the Haida people who had been coming to fish the Yakoun for longer than anyone could remember. A few of them were still lured back each season by their love for the rich, succulent salmon.

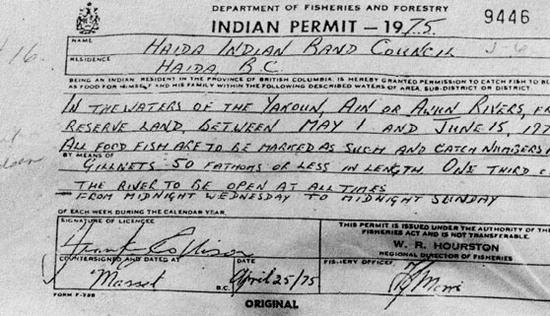

Inside a comfortable cabin a family of noble lineage made their evening meal of fresh roasted salmon. Outside, stapled to the cedar plank wall, a government permit from the Department of Fisheries and Forestry, issued under the Authority of the Fisheries Act, signed by the Director of Fisheries, gave them limited permission to catch the fish.

Eulachon Fishing

The contribution of the eulachon to the health and welfare of the Indian peoples makes it one of the important fish of the coast. The small, silvery fish, migrating in countless millions, were caught in enormous quantites. Some were eaten fresh and a great many dried, but the majority were rendered down for the rich oil they contained.

Often called “candlefish” (it is said you can light the tail of a dried fish and it will burn like a candle), the eulachon was also known as “salvation fish” since its arrival at the end of the winter meant so much to the food resources of the people. The Indian called it eulachon, a word pronounced with loose throat sounds difficult to spell with the English alphabet. In my research on this fish I have come across the following spellings, and there are probably more: eulachon, oolachon, eulachan, oolichan, hoolikan, hollikan, hollican, holligan, oligan, olachan, oulachon.

Eulachon spawn in a number of rivers on the mainland where the tides run strong. The migration lasts one or two weeks starting as early as the end of February in the north and continuing through to April in the south. Among the Tsimshian, the Nass and Skeena Rivers were major areas for catching the fish, as were the Kitimat River and the rivers of Knight Inlet for the Kwagiutl. The Bella Coola people fished the Bella Coola, Kimsquit and other rivers.

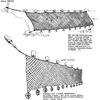

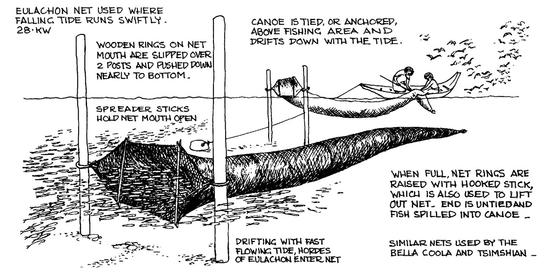

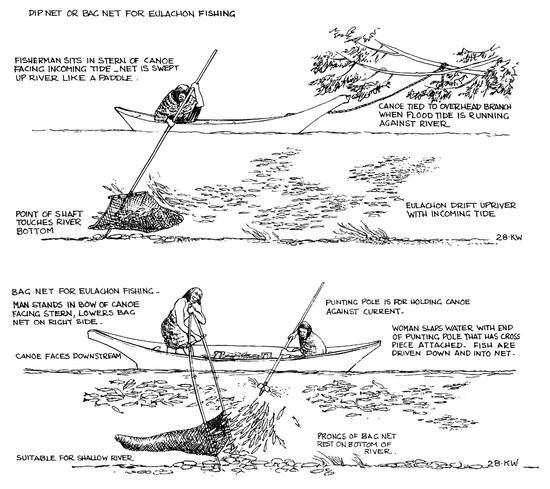

Most eulachon fishing was by net, and methods varied with different parts of the coast. At Fishery Bay, 14 miles inland from the mouth of the Nass, the river was still frozen over when the eulachon arrived and fishing was done through the ice. This ancient practice is still carried on today. People from the village of Greenville now travel the five miles down river to reach their ancestral fishing village by horse and sleigh.

The first wave of the eulachon run—the females usually preceding the males—were eaten fresh as a welcome change of diet for a people relying most of the winter on dried smoked fish. As the run built up and peaked, great quantities were caught for both preserving and oil rendering.

The Indian was not the only one to await and welcome the eulachon’s arrival. Sea lions, porpoises and whales followed the fish into the rivers; screaming hordes of seagulls filled the air, wheeling and diving to snatch at the glittering fish; bald eagles perched in trees along the river side, ready to swoop down and take their share. When the dead, spawned-out fish washed up on the river banks, the crows and ravens took the last of the feast.