Spiritual Realms

Prayers and Ceremonies

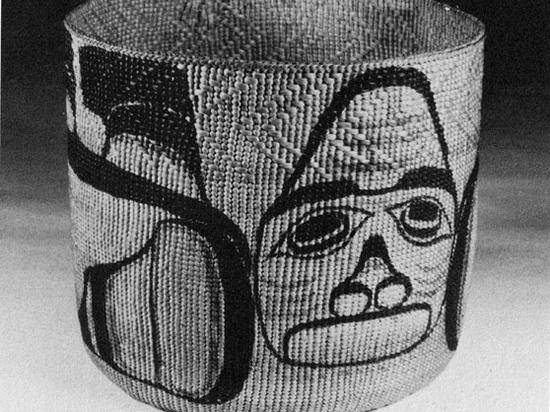

The Indians of the Northwest Coast showed much reverence and caring for the natural resources that were important to their cultures. They recognized that all living things—plant, animal, bird or creature of the sea—were endowed with a conscious spirit and therefore could present themselves in abundance or not at all.

There would have been years when the salmon came in extraordinary numbers and years when the run was poor or there was no run at all; years when the eulachon teemed up the rivers at a regular time and years when they came late; years when berries failed to mature and the picking was lean and years when the branches bent under the weight of the fruit. Most years migrating waterfowl would arrive in great flocks, but occasionally they would not. Since they saw the creatures’ coming as voluntary, the Indians reasoned that in a year of scarcity taboos had been broken or disrespect shown.

Writing in 1905 of the interior Indians of the Lillooet area, Charles Hill-Tout says:

“Nothing that the Indian of this region eats is regarded by him as mere food and nothing more. Not a single plant, animal or fish, or other object upon which he feeds, is looked upon in this light, or as something he has secured for himself by his own wit or skill.

“He regards it as something which has been voluntarily and compassionately placed in his hands by the good will and consent of the ‘spirit’ of the object itself, or by the intercession and magic of his culture heroes, to be retained and used by him only upon the fulfilment of certain conditions.”

Much the same attitude seems to have been prevalent among coast Indians. The “certain conditions” to be fulfilled were taboos, customs, and ceremonies that made an appeal to the spirit of the plant or creature to be harvested or caught. The ceremony might be simply a prayer—a supplication for success and abundance—and it showed humility, gratitude, and respect on the part of the human.

A prayer was said to the spirit of the great cedar tree before felling it, that it might fall in the desired direction. A prayer was said before the bark of the standing tree was stripped off, explaining what it was to be used for. It was a courteous apology as well as a prayer of thankfulness and recognition of so useful a material. The prayer was a gesture of reverence and a way of caring.

The fisherman used many different prayers and songs to communicate with the spirit of the fish and achieve success in fishing; these might be spontaneous, or acquired through spiritual experiences or in dreams. Those favoured with supernatural help guarded their songs and prayers with secrecy and became exceptionally good at fishing. Sometimes these individuals specialized in one particular kind of fish, earning an enviable reputation.

The Haida people of Skidegate said a prayer to the spirit of the mountain from which ran the salmon stream called Claig-a-doo, meaning “land of plenty.” If, at the end of September when the salmon came, the water was too low for their migration, the prayer beseeched the mountain spirit to make it rain and fill the level of the water so the fish could make their way upstream. 64.HA.

Sustenance for most of the people of the Northwest Coast was dependent on the return of the migrating species of salmon, and there were prayers said on the occasion of catching the first of the season, or of the run. The “First Salmon Ceremony” was a ritual of reverence and respect expressed in many different ways. Some people had a ceremony for the first of each species to be caught, some for just the first of the season; with some it was a family ceremony, with others the whole village participated. There were a ritual and prayers for catching the first load of eulachon. In each case the fishing season was not “open” until the ceremony had been performed.

The First Salmon Ceremony was also a celebration, a time of joy and renewal that brought cohesion to the village. It reminded the people of the rhythmic cycles in nature and the interdependence of all beings. It was a time to perpetuate the ancient customs and reinforce the regulating taboos. It was a time of thankfulness—for making it through to another year and for the return of the life-giving fish. The people looked forward to the start of the salmon run with great eagerness, for the dried fish of winter storage could be replaced with succulent red meat, fresh from the water.

Early running species of salmon will congregate at the mouth of a shallow creek before the spring runoff has swelled it sufficiently to allow them to proceed up to the spawning grounds. At this time, if a fisherman paddling a canoe in the vicinity saw a salmon jumping, he at once prayed to it:

"“Haya! Haya! Come up again, Swimmer,

"

that I may say ‘Haya,’ according to your wishes,

for you wish us to say so, when you jump, Swimmer,

as you are speaking kindly to me when you jump, Swimmer.” 66.KW

Also:

"“Welcome, friend Swimmer,

"

we have met again in good health.

Welcome, Supernatural One,

you, Long-Life-Maker,

for you come to set me right again

as is always done by you.

Now pray take my sickness

and take it back to your rich country

at the other side of the world,

Supernatural One.”

The man answered for the fish and said “Ha, I will do so.” 66.KW

The form of the First Salmon Ceremony was based on the normal activities associated with the fish—the handling, butchering, cooking, serving and eating—but it was embellished and made more affirmative, sometimes even dramatized. The method of taking the salmon up the beach to the house was often an elaborate one, testifying to the special occasion, and a new mat was made to lay the honoured guest upon.

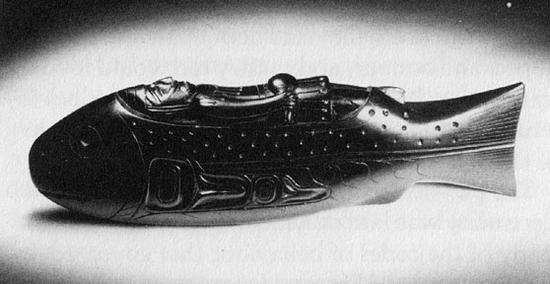

When a Kwagiutl fisherman trolling with hook and line for sockeye salmon caught the first nine fish, he clubbed them only once so that they were not quite dead. With a long twisted cedar withe he strung them through gill and mouth, tying both ends of the cedar to form a hoop. Holding each side of the hoop in his hands he prayed:

"“O, Swimmers, this is the dream given by you,

"

to be the way of my late grandfathers

when they first caught you

at your playground in this river.

Now you will be the same way, Swimmers.

I do not club you twice, for I do not wish

to club to death your souls so that you may go home

to the place where you came from, Supernatural Ones, you,

Givers-of-Heavy-Weight.

I mean this, Swimmers, why should I not go

to the end of the dream given by you?

Now I shall wear you as a neck ring going to my house,

Supernatural Ones, you, Swimmers.” 66.KW

The fisherman put the hoop over his head and it formed a ring similar to the cedar bark neck ring of the winter dances. He wore the ring of fish as he walked up the beach to his house and then, lifting it off, he held it in his hands and prayed:

"“O, Swimmers, now I come and take you into my house.

"

Now I will go and lay you down on this mat

which is spread on the floor for you, Swimmers.

This is your own saying when you came

and gave a dream to my late grandfathers.

Now you will go.” 66.KW

The ring of fish was placed on a new mat of cedar bark strips made especially for the occasion. The fisherman’s wife sat beside the mat, holding a fish with her left hand and a ground slate knife in her right. She prayed:

"“Thank you Swimmers, you Supernatural Ones,

"

that you have come to save our lives,

mine and my husband’s,

that we may not die of hunger,

you Long-Life-Maker.

Only protect us that nothing evil may befall us,

you, Rich-Maker-Woman,

and this also, that we may meet again next year,

good, great Supernatural Ones.” 66.KW

And she cut the fish with the slate knife in the accepted manner.

Another prayer for the first salmon of the season caught by hook was:

"“Swimmer, I thank you

"

because I am still alive at this season,

when you come to our good place,

for the reason why you came

is that we may play together

with my fishing tackle, Swimmer.

Now, go home and tell your friends

that you had good luck on account of coming here,

and that they shall come with their wealth bringer,

that I may get some of your wealth, Swimmer,

also take away my sickness, friend,

Supernatural One, Swimmer. 66.KW

At the mouth of the river where the congregating salmon were plentiful and the water clear, the first fish was often speared from the bow of the canoe. Clubbing it once, and holding it in his hands, the fisherman prayed to it:

"“We have come to meet alive, Swimmer,

"

do not feel wrong about what I have done to you,

friend Swimmer,

for that is the reason why you came,

that I may spear you,

that I may eat you,

Supernatural One, you, Long-Life-Giver, you,

Swimmer.

Now protect us, me and my wife,

that we may keep well,

that nothing may be difficult for us

that we wish to get from you,

Rich-Maker-Woman.

Now call after you your father and your mother,

and uncles and aunts

and elder brothers and sisters

to come to me also, you Swimmers,

you Satiater.” 66.KW

When the first four silver salmon (coho) were caught by trolling, the fisherman’s wife met her husband’s canoe at the beach and said a prayer of welcome to the fish. She brought them up to the house and butchered them according to custom, leaving the heads and tails still attached to the backbones. These she set in the roasting tongs to cook by the fire. When the eyes of the fish were blackened, the family group was assembled in the house, and they sat behind the fire. The tongs with the roasted fish were laid on new mats spread before the people, who were given water to drink. The one of highest rank then prayed to the food before it was eaten:

"“O friends! thank you that we meet alive.

"

We have lived until this time when you came this year.

Now we pray you, Supernatural Ones, to protect us from danger,

that nothing evil may happen to us when we eat you,

Supernatural Ones!

For that is the reason why you came here,

that we may catch you for food.

We know that only your bodies are dead here,

but your souls come to watch over us

when we are going to eat

what you have given us to eat now.”

“Indeed!” 66.KW

After eating, the family wiped their hands on shredded cedar bark, but did not wash them. The wife gathered up the bones and all that was not eaten into the mat, and threw it into the sea, including the mat, thus ensuring that the salmon would become whole again and return to the land of the Salmon People. Others of their species seeing them knew they had been treated with due respect and honour, and so they too would follow up the river. It seems the custom of all the tribes to return the bones to the water, with the exception of the Tsimshian, who burned them in the fire.

The pattern for the Tsimshian First Salmon Ceremony was laid down in a myth, as were many of the codes of behaviour that governed certain aspects of life, and from this it is not difficult to envision the solemnity and joy of the celebration of the return of the salmon.

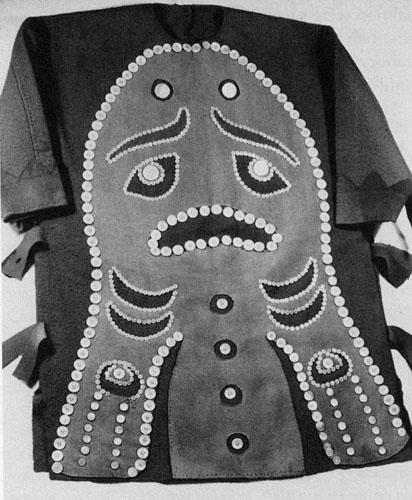

When the first salmon of the season were caught, four elderly shamans were called down to the fishing platform at the water’s edge from which the fish had been caught. They brought with them a cedar bark mat, freshly made for the occasion; eagle down, symbol of peace and friendship, and red ochre. One of the shamans put on the garment worn by the man who had caught the fish, and painted his face with the ochre. In his right hand he held his ceremonial rattle, and in his left an eagle tail, the long black feathers tipped with white.

The four shamans carefully placed the salmon on the new mat, and holding it by the four corners carried it up to the chief’s house, the place where special guests were always taken. The shaman wearing the fisherman’s raiment led the procession, shaking his rattle and swinging the eagle tail, eagle down on his head floating to the ground. Eventually they reached the big plank house of the chief, where young people having recent contact with birth and puberty (the ritually unclean who might offend the salmon) were required to leave.

Old people led the procession into the house, and they were followed by all the shamans of the village dressed in colourful ceremonial regalia.

Amid the continued singing of special songs, the honoured fish was placed on a cedar board, and four times the shamans encircled it, rattling their beautifully carved rattles and swinging the eagle tails. The singers finished the songs and seated themselves in the proper place around the house. The fire crackled, making light and shadow patterns along the roof beams and the sturdy walls.

All was hushed. The shaman wearing the fisherman’s garment called upon two old women shamans to cut the fish, for butchering fish was traditionally women’s work. With a mussel shell knife the salmon head was first severed, then the tail, followed by a cut along the ventral side to remove the inner parts. All the people assembled maintained silence, and as the fish was being cut, the women shamans called the salmon by honorary names of great significance: “Chief Spring Salmon… Quartz Nose… Two Gills On Back… Lightening Follow One Another… Three Jumps.” 68.TS

The giving of names bestowed high social privileges, and the first salmon of the season was thus being honoured. Finally the fish was cooked in the prescribed manner and shared among the guests. When they had finished, all the bones, entrails and any uneaten parts were gathered up carefully into a clean mat and ceremonially put into the fire. This ensured the fish’s revival and return to its home in the Spring Salmon village out in the sea. Since it had been well treated and duly honoured, the other salmon would follow up the river.

With the ceremony concluded, the catching of great quantities of the fish could then proceed.

Among the Comox people of the Coast Salish, the First Salmon Ceremony for sockeye involved the Ritualist (a shaman) who stood on a platform singing a secret spiritual song, shaking his ceremonial rattle. His face was painted with red ochre and there was eagle down in his hair, symbol of peace and welcome. He then took his canoe out and harpooned several sockeye, putting to one side the first one he caught.

Everyone was on the beach anticipating his return. He carried the first salmon gently up to his house, where his immediate family gathered, and they too had eagle down on their heads as a symbol of welcome to the fish. The Ritualist sang special songs while he shook his rattle, and honoured the fish by sprinkling eagle down over it. When the salmon had been boiled, everyone in the family shared the meal, including the children.

The following day all the villagers were invited to the Ritualist’s house for a feast, and they ate the remainder of the salmon that had been harpooned. With the ceremony over, all the families were then entitled to go out fishing.

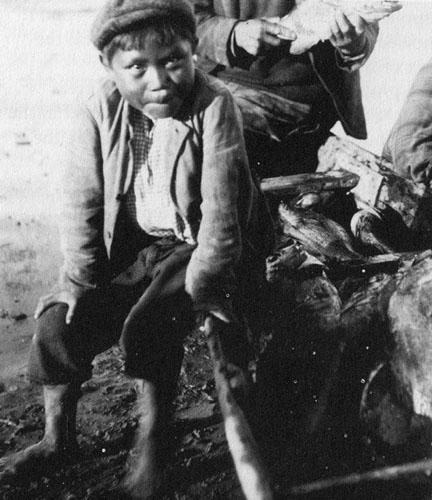

The Saanich, to the south of the Comox, practised a variation of the ceremony when the Ritualist, with helpers, caught several sockeye with the reef net. When they returned to the beach, the people had formed an avenue from the water’s edge up to the cooking fires. Children, with red ochre painted faces and white eagle down in their shining black hair, each carried up a salmon by holding the dorsal fin in their teeth. They stroked and soothed the fish as they went in procession up the avenue, with the Ritualist singing songs to the fish and shaking his rattle. At the fire, his wife was directed by him on how to cut and roast the fish, which were cooked over alder fires in trenches. The salmon, served on long planks of split cedar, had to be handled so that the heads always pointed inland or upstream, the direction the run was to go. At the conclusion of the meal, all the bones were gathered up and returned to the sea. 69.CS

Across the water from the Saanich were the Squamish on the mainland (also Coast Salish), who had a different custom involving the children. Anthropologists describe how the youngsters there carried the salmon up the beach from the canoe in small slings they had made of flexible cedar branches, one for the head and one for the tail of each fish. After conveying the fish to the Ritualist’s house, they returned to the beach and shouted up river, “We’re going to break its head off!” 69.CS (I can’t help feeling that something has been lost in the translation here!)

Among the Haida and Tlingit people there was no salmon ceremony. For them the fish was less abundant, and they were not dependent upon it since they were able to catch in great quantity the great halibut, a fish that could also be preserved and stored for winter.

The Kwagiutl halibut fisherman prayed when putting tackle into the water. Once in the canoe with all his gear he set out on the incoming tide. But first he drew alongside a rock, plucked seaweed from it and rubbed it all over his hands, and held them underwater. This was to remove the human scent before handling the hook and bait, since he knew the fish had a sense of smell. While cleansing his hands he prayed to the halibut, using the customary term “Old Woman” and other nicknames, and referring to the hook as “younger brother.”

"“O Old Woman! Look at my work on your behalf.

"

Now this is clean, my younger brother,

with which I am going to catch you… yes, yes.

After he attached the bait to the hooks, and set the lines, the sinkers and the bladder floats, he further beseeched the halibut:

"“Top bladder, go on, Old Woman!

"

Crawl up to it. Now it is well prepared.

This is your sweet food,

You, Wrinkled-In-The-Mouth!

You, Squint-Eye! Go on, go on,

else I may be stiff when I leave this place,

Old Woman!”

Before long Old Woman took the sweet food and as he hauled in the long line the fisherman prayed to Younger Brother, the hook, not to lose the catch:

"“This is what I was wishing, Old Woman,

"

not to wait long on the water for you.

Now hold this my younger brother.

Don’t let go this my younger brother.”

With all the gear and the halibut stowed safely into the canoe, he took his fish club in one hand and prayed to the fish:

"“Now come, Old Woman!

"

Now you have enough to eat,

now you have tasted your sweet food.

Now I shall give you this sweet food

as your second course.” 10.KW

And the halibut was killed with a blow on the head. Another prayer beseeching the halibut to take the bait was:

"“Now go to it, Scenting Woman.

"

do not play at your sweet tasting meat.

Take it at once, Born-To-Be-Giver.

Go ahead Old Woman, take your sweet tasting food.

Do not let me wait long on the water.

Go ahead, come on,

my younger brothers are dressed with your sweet

tasting food,

O Flabby-Skin-In-The-Mouth.” 66.KW

There was also a prayer addressed to the hook while it was being made:

"“O Younger Brother, pay attention.

"

Now Younger Brother, your dress has been put on.

You will go to the village of Scenting Woman,

Born-To-Be-Giver-of-The-House,

Old Woman, Flabby-Skin-In-The-Mouth.

Now clean and purify yourself, Younger Brother,

Do not let go of Old Woman…

when she takes hold of you, good Younger Brother.

I shall blacken you, Younger Brother,

with these spruce branches, that you may smell good,

that you may be smelled by Scenting Woman

when I first put you in the water.” 66.KW

A simple ceremony marking the catch of the first halibut of the season was observed by the Kwagiutl. There were no doubt many variations of this, but one demanded that the fish be butchered and cooked without delay, following a specific procedure.

The flanks were removed for drying, and all the rest steamed in a pit with eel grass, broadleaved grass and hot rocks. The fins were roasted over the fire in a grid of split cedar sticks. Guests, invited in to share the meal, put all the bones and other uneaten parts on a new mat placed before them. After the meal all the scraps, and the guts also, were gathered up into the mat, the contents tossed back into the sea and the mat washed.

Were the fisherman not to observe this ritual, he would not get another bite. 28.KW

Eulachon, so important for the rendered oil, was also recognized with a ritual when the run began. A chief, with the privilege of catching the first of the eulachon, went in his canoe to a special place in the river, tying the canoe up to a particular overhanging branch. It was always the same place. Taking up his dip net, he addressed it in prayer that it might be successful:

"“Go on, friend,

"

on account of the reason why you came,

placed in the hands of my late ancestors

by our Chief Above, our Father,

and go and gather in yourself the fish,

that you may be full when you come back, friend.

Now go into the water where you may stay, friend.” 66.KW

He then partially lowered the dip net three times, and pushed it right down for the fourth. When it was hauled up he prayed to the shimmering mass of fish writhing in the net:

"“Now come, fish, you who have come

"

being sent by our Chief Above, our Praised One,

and you come trying to come to me.

Now call the fish to come and follow your magic power

that they may come to me.” 66.KW

The chief then poured the hundreds of slender, silver fish from the net into the canoe. Four times over he did this to complete the ceremony, and then returned home. All fishermen were then allowed to start harvesting the oil-rich fish that came in millions every year. When each man pulled up the first in his dip net, he offered a prayer of gratitude to the eulachon. There were different ways of saying it, but a common prayer was:

"“Thank you, Grandchildren, that you have come to me

"

to make me rich as it is done by you, fish,

you Dancers. You will protect me

that I may see you again next year, Grandchildren.

Thank you that you do not disdain trying to come to me,

Supernatural Ones.” 66.KW

Another prayer was:

"“Now you have come, Grandfather, you fish,

"

that you may not ill-treat me,

that you may only bring good luck by your coming to me,

Supernatural Ones, you Dancers, I pray you,

Supernatural Ones, that we may meet again next year,

and please, protect me, friends, you fish.” 66.KW

Tons of eulachon were rendered for their oil each year, but great quantities were also strung up to dry, and a prayer of welcome was said to the first to be strung:

"“Now welcome, fish, you who have come,

"

brought by the Chief of the World-Above,

that I see you again,

that I come to exert my privilege

of being the first to string you, fish.

I mean this, that you may have mercy on me

that I may see you again next year

when you come back to this happy place, fish.” 66.KW

There were many ways of greeting and honouring the different kinds of fish, and a great variety in the prayers offered to both the fishing gear and the species of fish. These tributes were far more profound than they might appear; they were deeply significant to a people who based their way of life on the natural rhythms of their environment, a people who had a close spiritual relationship with the plant and animal kingdoms of their coastal world.

The significance of the prayers and ceremonies cannot be fully understood by those of us who were not a part of the culture, but they nevertheless convey a message as meaningful today as it was a thousand years ago. It is a legacy of wisdom: that to honour and respect the resources of the sea and river is to ensure their continuous abundance for all time.

Beliefs, Customs and Taboos

Because the fish of the river and sea were life itself to the coast Indian peoples, rules (customs and taboos) arose to regulate the activities connected with fish and fishing, and beliefs gradually surrounded the mystique of a never-ending supply of food from the waters. Because the five species of salmon were, for the majority of the coast cultures, the most important of all the fish, there were more beliefs and customs about salmon than about any other fish.

Some of these beliefs have about them a certain charm, while many touch on the attitude of caring for the fish as people, and of reverence for their role in life. Some are fearful, and some seem difficult for us to equate with present day society and our knowledge of biology. But these were the thoughts of a people living intimately with the river and sea, a people with their own way of understanding the intricacies of biology. For them it worked, and it worked unimpaired for thousands of years.

While many beliefs, with variations, were widespread and shared by many different cultures of the coast, others would be more localized, belonging to a region, a band, or perhaps a single village.

Without attempting to analyse the reasoning, here is a sampling of various beliefs and customs I have come across and found worth remembering.

- It was a general belief along much of the southern coast that the salmon were really people who lived in villages in a magical place under the sea, at the edge of the horizon. Five villages housed the five tribes of Salmon People, each with its own habits and breeding places. At specific times of the year these people transformed themselves into fish and swam up the rivers after journeying through the sea. Some fishermen believed the fish were led by their chief, who would then be the first one caught, and therefore must be accorded such honour as befits a chief. But others believed they sent scouts out ahead, and if the scouts were not treated with courtesy and respect when caught, then other salmon would not follow to ascend the river.

- Shamans could tell when the salmon would arrive. In visions they could see them as they headed across the open sea or up the inlets to the rivers. 68.TS

- Twins had great rapport with salmon, and many varying customs grew out of this general and fairly widespread belief.

- Twin children would be sent down to the river bank, or out into the stream if it was shallow, to call the salmon, singing special songs and shaking rattles to entice the fish into the traps. 69.KW

- Twins had the power to call the eulachon as well as salmon. 69.TS

- The father of twins held special powers in the salmon world. During fishing season he would spend a great deal of his time and energy in singing and performing secret rituals to ensure a maximum salmon catch. 69.TS

- Twins of the same sex were salmon before birth. 69.KW

- The appearance of twins forecast an unusually large salmon run. 69.NK

- A twin child would burst into tears if a salmon was mistreated. 69.NK

- If a young girl saw a salmon jumping in the creek within a year of her puberty, all the salmon would leave the creek. 69.HA

- An evil-minded person could cause the salmon run to cease by burying the heart of a salmon in a clam shell, or in a burial ground. 42.CS

- If roasted salmon eyes were kept overnight in the house, and not eaten, all the salmon would disappear from the sea. 69.KW

- Salmon were responsible for the birth of twins and many of these people could assume salmon form at will.

- Using a stone or metal knife to cut fish in the First Salmon Ceremony would cause thunderstorms or some other disaster, so a shell knife had to be used. 68.TS

- Like people, salmon must enjoy eating the sweet inner bark of the hemlock in spring; so balls of it were rolled up, stuck with feathers, and sent floating down the river to the fish.

- Salmon hanging up on the drying racks would play among themselves when no one was watching. 42.CS

- When the dog salmon returned to their village in the sea, having been up the Fraser River, they brought back songs they had learned from the people along the way, and spent most of their time singing these songs. 70.CS

- Only old women past the age of childbirth were allowed to work on making or repairing salmon nets.

- A piece of Devil’s Club (Oplopanax horridus) was wrapped around the halibut hook before the bait was tied on, as a good luck charm. 74.HA

- When a halibut was caught, it was laid on its back in the canoe, head towards the fisherman; otherwise he would have no more bites. 67.KW

- Flicker feathers were often tied to fish hooks to bring good luck. 62.HA

- The Sun Dew (Drosera spp.) was a good-luck plant used by a fisherman. He would tie it on the end of his net to ensure a good catch, and if he did this without anyone knowing about it, the catch would be even greater. 74.HA

- To comment on the great number of fish being caught was considered unlucky. 32.CS

- When a codfish was caught that was too small, it was set free and told to send its big brother. 40.CS

- A lunar eclipse was caused by a codfish swallowing the moon. 72.NK

- It was considered ominous to catch a salmon having a twisted mouth, and it was therefore necessary to have it exorcised by a ritualist who then returned it to the water. 32.CS

- If herring failed to spawn, a male and a female herring were tied together and twins led them, on a string, into a bay where they were released. 40.CS

- The sturgeon was often referred to as “Sister” while being fished (70.CS) and the halibut as “Old Woman,” among other names. 67.KW

- Similarly the red snapper was never mentioned by name during the fishing, but rather was referred to as “High Class Person.” 40.CS

- When a lamprey was cooked, the head, still on its stick, was thrown. If it travelled far the thrower would have a long life, but if it fell short then a short life was predicted. 42.CS

As in cultures all over the world, many and varied were the “dos and don’ts” surrounding the Indians’ staple food. Most taboos are based on a belief or a necessity, and persist because of conditioning and habit even when they seem incongruous. A severe custom was that of the Bella Coola people who made the throwing of refuse into a stream during the salmon run punishable by death. (71.BC) If this ruling stemmed from the attitude of showing great respect for so revered a personage as the salmon, the underlying aim might well have been safeguarding clear water for the migration and spawning of this life-giving resource.

Other prohibitions regarding the river were enforced during the salmon run. Freshly split planks could not be floated down the river, and a new canoe had to wait ten days before being launched. The reason for this is not documented, but I find it interesting that research scientists today believe that naturally occurring wood extractives of cedar (from which the planks were made) are toxic to fish, as they are to other forms of life.

There would also seem to be good reasoning behind a taboo directed towards the women and children of the Katzie Band of the Coast Salish: during the sockeye run, women must not make any mats because Sockeye Salmon Women, in the land of the Salmon People far out in the ocean, did not make mats. To do so might offend the fish who could inflict a sickness on the mat-making women. Also, since the Sockeye Children had put away their play things to leap into the water and change into fish to go up the river, so the children of the village must put away their favourite play things until the run ended. 10.CS

No doubt mat-making among a group of women was also a time for idle chatter and gossip, and since the men would be constantly busy with the task of catching the salmon, I suspect that such taboos were to ensure that the maximum amount of time of both women and children was spent in butchering, cleaning, smoking and preserving the catch.

A variety of taboos and customs were observed in the catching, cutting, handling, serving and eating of fish, and again most of these evolved around the hallowed salmon.

- If a fisherman caught two salmon on a single thrust of his two-pronged harpoon, he must not show any excitement or jubilation, but remain quiet; otherwise all the salmon already drying on the racks would get down and return to the sea.

- The first catch of salmon was never sold for fear that the hearts might be destroyed or fed to the dogs, for this would seriously affect the run. 69.CS

- Children were not allowed to play around with the salmon before they were cleaned; to do so would offend the fish, who would cause the child to become ill and pant the way a salmon does when it is dying. 42.CS

- The intestines of a salmon caught by spearing had to be broken off at the anal fin, not cut off, or else the spear would break when next in use. Similarly, a salmon caught by hook had the intestines cut off at the anal fin, not broken; otherwise the fishing lines would break. 69.KW

- A pregnant woman was not to split salmon in half or she would give birth to twins. 65.KW

- Those who had recent contact with puberty, birth or death (that is, the ritually impure) might not handle or eat fresh salmon. It would offend the fish and the run would cease. 68.TS

- When twins were born at a fish camp, the parents were sent back to the village and prohibited from eating any kind of fish. 69.MK

- Salmon might not be taken up the beach from the canoe in a basket; they had to be carried up one in each hand. 72.NK

- Blowing on hot, freshly cooked eulachon to cool it was taboo; this would bring windstorms. 73.TS

- Drinking water with a meal of eulachon was forbidden; to do so would bring rain and spoil the oil rendering. 73.TS

The reader may be tempted to laugh at the primitive thinking of people who would observe such taboos, finding them unfounded and absurd, but consider the belief of my friend. Serving tea to a casual group of friends, she was insistent that no woman other than herself pour from the same tea pot, for then she would become pregnant again.

Songs

Fond of music, rhythm and dancing, the Indian peoples had songs for both their everyday and ceremonial lives. Many songs, some supernaturally inspired, were the personal property of chiefs, families or individuals and they alone held the right to sing them. There were also songs of a more general nature, and both often referred to experiences of life which, quite naturally, included fishing.

This lullaby for a boy was concerned with spear fishing:

"“I, the slave woman,

"

am glad in my heart,

I will spear a whole salmon for you,

I am glad in my heart…

I will snare what you are going to eat…

I, the slave woman,

am glad in my heart

I will spear a whole salmon for you…

Our three spear poles will be used [all] at once

to catch salmon.

You will fill yourself with meat, O my sister.

Why are you looking for meat?

It is only the salmon eggs that really fill you.

Yes, I got filled with salmon eggs.” 82.TS

The first part of another lullaby for a boy looked forward to the time when the child would become a man:

"Mother:

"

“Dear boy, dear boy,

dear little boy…”

Reply from the child:

“Sit up at night, my sister,

Sit up with me at night,

O my sister to make me grow,

til I become a man.

Then I will go to the creek of my forefathers

Where I will catch the large spring salmon.

Then I will fish at Echo Cliffs,

That is where I will gather the backbones

or fish spines for Thunder-Woman…” 82.TS

Young boys casting for trout sang a song that was a kind of “dare” to the fish:

"“Come along, trout,

"

I want to triumph,

I want to triumph

Over you biggest trout.

I fish for trout,

I fish for trout.

Swallow [the bait] right down

To your very tail,

To your very tail,

Why, you cannot even break one of our hairs”4 80.BC

Typical of the frolicsome chants of youth, the following was sung by boys splashing in the water trying to drive minnows ashore:

"“Who is your father?

"

Who is your father?

Rotten stomach is your father,

Rotten stomach is your father.” 80.BC

A beautiful and ancient song is that of a chief, sung at a potlatch before the distribution of gifts:

"“I will sing the song of the sky.

"

This is the song of the tired—

the salmon panting as they swim up the swift current.

I walk around where the water runs into whirlpools.

They talk quickly, as if they are in a hurry.

The sky is turning over. They call me.” 82.TS

__________

4. Refers to braided human hair used in fishing lines.