1. Beginnings

The rich culture and societies of British Columbia’s First Nations did not collapse the moment British explorer James Cook sailed into Nootka Sound on a blustery March day in 1778. In fact, for the next hundred years, despite the toll taken by smallpox, alcohol and guns, many First Nations more than held their own. On the coast, with their sophisticated governance based on clans and an existence based on salmon and cedar, the First Nations were among the most advanced and diverse in the Indigenous world. When BC entered Confederation in 1871, Indigenous people outnumbered non-Indigenous people nearly three to one; not until 1891 did non-Indigenous residents represent a majority of the population. Missing from most history books has been the role Aboriginal people played in driving the pioneer economy. For much of the nineteenth century, in addition to sustaining the critical fur trade, First Nations provided the bulk of wage labour in British Columbia. Logging, sawmilling, longshoring, mining, farming, canning and fishing all featured significant numbers of Indigenous workers in the workforce, willing to trade their labour for wages to improve their own lives and communities. The importance of First Nations to the growing settler economy was made clear by the province’s attorney general in 1871:

"Every Indian who could and would work was employed in almost every branch of industrial and domestic life, at wages which would appear … high in England or in Canada. From becoming labourers, some engaged in their own account in stock breeding, in river boating, and in packing, as carriers of merchandise by land and water. Others followed fishing and hunting with more vigour than formerly to supply the wants of the incoming population. The government frequently employed those living in the interior as police, labourers, servants, and as messengers entrusted with errands of importance.

"

Cook was not the first European to land on the BC coast, but it was his arrival that set the wheels of change in motion. Once white traders discovered the value of sea-otter pelts in China, the demand for the sleek, luxuriant fur was insatiable. Scores of ships plied the West Coast seeking furs that the inhabitants provided in staggering numbers. Skilled First Nations traders accumulated iron chisels and other metal tools and adornments, blankets, clothing, cloth, molasses, rice, bread, biscuits, guns and alcohol. Within just a few decades, the once plentiful sea otter was hunted to virtual extinction, but the more traditional land-based fur trade continued. None of it would have been possible without the province’s First Nations, both men and women, who fed, guided and mostly welcomed the early fur traders and explorers as well as providing the furs once trading posts were established.

As with coastal First Nations, whose first word to Cook was makúk (“let’s trade”), trade was hardly new to the Indigenous people of the BC Interior. They had been trading for centuries via a network of age-old trails that elaborately wound through difficult terrain. In particular, there was the storied “grease trail” that carried precious oil from the oolichan to almost everywhere. Both West Coast and Interior Indigenous people had been quick to embrace trade in furs. Each new post, including the key colonial trading hub of Fort Langley, was quickly surrounded by native encampments anxious to barter whatever they had, including labour, for new possessions.

When Fort Victoria was erected in 1843, the Lekwungen (whom settlers called the Songhees) moved their biggest village close to the fort and even helped build its large stockade, receiving one blanket for every forty pickets they cut. With so few non-Indigenous people on hand, there was plenty of work to be had. By 1853, the Lekwungen had amassed sufficient wealth to host a massive potlatch attended by three thousand guests, sparking a seasonal migration of several thousand Indigenous people every year over the next three decades, some of them canoeing as many as a thousand kilometres to spend six months or so near Victoria. Governor James Douglas wrote in 1854 that they were drawn “by the prospect of obtaining employment as labourers and procuring by their industry supplies of clothing for themselves and families.”

The opportunity for Indigenous people to trade goods enhanced many aspects of their daily lives without serious disruption. Throughout the fur trade, they retained control of their traditional territories. Fur traders were not settlers; most got along with those who permanently inhabited the land. When one fur trader tried to push his weight around against the “savages,” Chief Kwah of the Dakelh Nation near Fort St. James, who supplied abundant salmon to the trading post, spoke for many with his dignified resistance when he reminded trader Daniel Harmon: “Do I not manage my affairs as well as you? When did you ever hear that I was in danger of starving? I never want for anything, and my family is always well clothed.”

Vancouver Island became a Crown colony in 1849—not long before things began to change. Within a few decades, the economy of BC was taken over by the beginnings of a rampant capitalism reaping as much profit as possible from the province’s rich resources—a formula that remains in place today. BC’s abundant supply of timber, minerals and salmon was opened up for mass exploitation. Working for wages soon eclipsed the fur trade. Yet for most of the next fifty years—even as many of their villages were decimated by disease—Indigenous people continued to adapt. When jobs were to be had in the nineteenth century, they were glad to take them; their sweat and toil drove much of BC’s early resource economy.

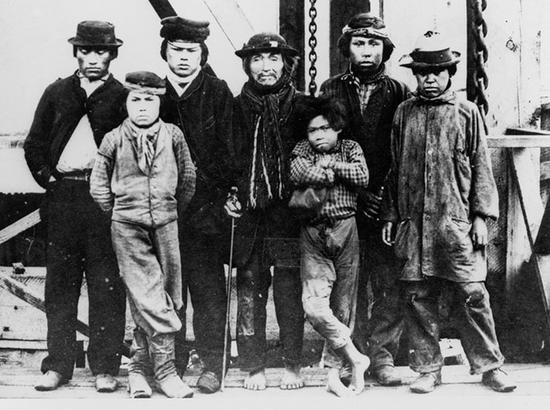

First Nations were in the thick of the muddled, unassuming start to the fledgling resource boom. Members of the Kwagiulth subgroup of the Kwakwaka’wakw First Nation alerted the Hudson’s Bay Company to the presence of surface coal near their village by present-day Port Hardy. With the advent of steamships, coal had become a valuable mineral, and the HBC established Fort Rupert to extract it in 1849. The first miners were the local Kwagiulth inhabitants who mined the surface coal with axes and crowbars, then transported it to offshore ships by canoe, receiving one large blanket for every two tons of coal. At the same time, the Kwagiulth asserted their ownership of the coalfields, forcing Douglas to negotiate a treaty to gain access.

A cockamamie scheme was hatched to import a group of experienced Scottish miners to sink shafts and mine the more lucrative underground coal seams. Most of them eventually deserted Fort Rupert for the California gold rush, with the help of a rival Kwakwaka’wakw group, the Nahwitti. Douglas complained that the Scottish miners had not “turned out a single bushel of coal since their arrival, all the coal we have hitherto sold being the produce of Indian labour.”

Among a group of Scotsmen hired to replace the deserters at Fort Rupert was a man who would dominate the BC coal-mining industry for more than thirty years. Robert Dunsmuir, as hard as the rock faces that made him wealthy, was perhaps the most merciless foe workers in British Columbia ever faced. Beset by scurvy, loss of life and harrowing sailing conditions, Dunsmuir’s trip from Scotland lasted nearly eight months—after he agreed to go on barely a day’s notice with his wife pregnant. On arrival, Dunsmuir separated himself from the other miners, impressing his overseers by completing his contract. When coal petered out in Fort Rupert, the HBC dispatched him to Nanaimo, where local First Nations had identified an abundance of deeper, thicker seams. There, in time, Dunsmuir founded his empire.

As in Fort Rupert, the Indigenous inhabitants of the nearest Snuneymuxw villages were the first miners, gleaning surface deposits and loading the coal onto ships by canoe, lugged and transported by women who earned tickets for blankets and shirts at the company store. Like the Kwagiulth, they too claimed ownership of the coal seams, forcing Douglas to compensate them and negotiate another treaty to obtain clear access. The 1854 agreement with the Snuneymuxw was the last of the fourteen so-called Douglas Treaties signed with Vancouver Island First Nations. All received compensation, recognition of their existing village sites and surrounding fields, plus the unrestricted right to continue hunting and fishing on the large tracts of traditional territory they gave up.

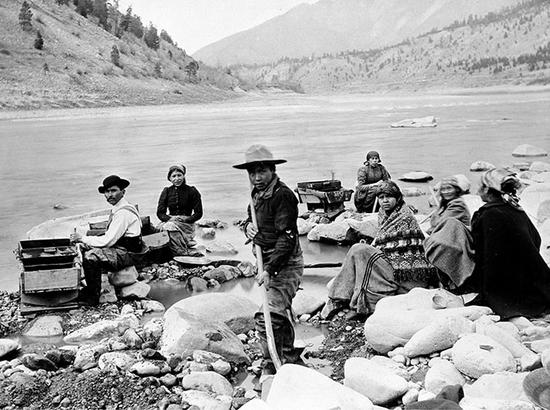

In 1858, news of gold found along the Thompson River reached San Francisco, where hordes of penniless miners who had failed to strike it rich in the fabled California gold rush of 1849 still lingered. Soon, tens of thousands of unruly prospectors were making their way to the distant canyons and riverbanks of the Fraser and Thompson Rivers. There were no laws, no authorities, no regulations and plenty of Aboriginal people who had inhabited the region for eons. Alarmed, Douglas rushed to the region to assert sovereignty and in August the British government established a second colony, calling it for the first time British Columbia. But this did not head off a little-known brief but bloody conflict between the Nlaka’pamux First Nation and several vigilante militias formed by the gold-rush invaders. Numerous casualties occurred before the parties agreed to a truce that promised tolerance for the rights of both sides.

By the end of the year more than twenty-five thousand rambunctious, predominantly American newcomers had pushed through Victoria and were strung out in makeshift camps along the Fraser and the Thompson. Rarely in any gold rush had so many arrived in such a short time. The pickings proved relatively modest, however, and most moved on to try their luck elsewhere, particularly in the Cariboo where a new gold rush erupted. But the sudden, dramatic influx of 1858 was the beginning of British Columbia’s modern history.

Victoria became a bustling outpost overrun by thousands of miners waiting for their licences to prospect. Businesses emerged like mushrooms after a heavy rain to supply the miners with dry goods and materials. In the former wilds, crude transportation and horse-packing networks sprang up to deliver the miners and their bulky possessions to the gold fields. Local Indigenous people again showed their willingness to work. They panned and dug for gold, they were hired to help white miners work their claims, and they kept the miners fed and supplied, skillfully packing in goods through the harsh, rocky terrain by horseback. Indigenous labourers maintained their packing dominance until motor vehicles came along in the early part of the twentieth century.

For a brief time, during the larger and more lucrative Cariboo rush a few years later, the pop-up wilderness community of Barkerville was the continent’s largest city north of San Francisco and west of Chicago. A significant number of the thousands who sought gold were Chinese. In addition to mining, some Chinese immigrants went into business, establishing BC’s first Chinatown on the outskirts of Barkerville. Although the frenzy eventually died out, there were now roads and steamship services into the Interior and the beginnings of thriving settlements.

For the working people of British Columbia, the gold rush also launched the province on the journey from which it has never veered, an economy based on harvesting riches that only had to be found to be exploited. Alone among Canada’s provinces, with only 4 percent of its large, forbidding land base suitable for growing, BC was not nurtured by agricultural roots. By and large, it was shaped by a capitalist thirst for natural resources and the sweat of industrial labour. Historian Martin Robin assesses BC as a province “primarily built by the working class,” amid a corporate entrepreneurship that was “speculative, acquisitive and adventuresome.” While it took thirty more years for Indigenous people to be supplanted as British Columbia’s main workforce, the great transformation was now in motion. Settlers, not fur traders, were dictating the future.

The road to what became by far BC’s number-one industry started in the 1860s with small-scale logging and sawmills to cut the timber. As the forest industry expanded, Indigenous people flocked to the mills and woods to do the work. On Vancouver Island and along Burrard Inlet, all newly built sawmills relied on Indigenous workers, many of whom travelled from far up the coast for the chance to earn wages there and across the border in Puget Sound. Pay was not all that bad for the time, said to be between at least $20 and $30 a month plus board at several Burrard sawmills in 1875.

Although claim to the province’s seemingly infinite forests, featuring some of the tallest trees in the world, was unceremoniously taken from those who had frequented them for millennia, that didn’t stop Indigenous loggers from harvesting them. Until increased mechanization and more regulated production methods cut into the industry, hand-logging was part of the work rhythm of many Indigenous labourers. Legendary Squamish chief August Jack Khatsalano started in the forest industry at a young age in False Creek sawmills and developed a successful logging partnership that he ran into the 1930s.

On the docks, as the port of Vancouver developed to handle the province’s budding export trade, nearly all the heavy lifting was initially done by members of the Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh Nations just across the waters of Burrard Inlet. As time went on, these longshoremen became famous for their ability to load lumber, a specialized niche of the trade they dominated for decades, praised by the likes of timber baron H.R. MacMillan for their speed. “They were the greatest men that ever worked the lumber,” said veteran dock worker Ed Long. Chief Joe Capilano worked lumber on the waterfront to help finance his historic trip to London in 1906 to present a petition of First Nations grievances to King Edward VII. The longshore tradition continued well into the twentieth century, producing three different incarnations (1906–07, 1913–16 and 1924–33) of a primarily Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh union local known to everyone on the waterfront as the Bows and Arrows, and providing Chief Dan George a living for twenty-seven years before he became a celebrated actor in the 1970s.

But no industry was more central to BC’s Indigenous people than fishing. Celebrated in their art and culture, salmon drew Indigenous people to the coast and to the great rivers of the Interior. The West Coast’s rich annual salmon runs, particularly of sockeye, sustained First Nations villages for almost the entire year. So when BC’s post-Confederation resource boom began to recognize the value of salmon, Indigenous people were in the forefront. From the 1870s onward, thanks to the Industrial Revolution, cheap canned salmon found a huge market among millions of British workers driven from agricultural land to factory sweatshops. With so much money to be made and the salmon there for the taking, a second gold-rush mentality began to sweep the Fraser.

Some of the most prominent corporate tycoons in BC got their start in the business of canning salmon. By the end of the century, dozens of canneries dotted the coast and lined the banks of the Fraser and salmon rivers farther north. For the better part of that time Indigenous men did almost all the fishing, working from dawn to dusk in small gillnet skiffs supplied by the canners. Couples often worked together, the men catching salmon for $2.25 a day and their wives working the oars for a dollar.

Indigenous women were vital to the industry. Besides helping on the fishing grounds, they worked inside the canneries, sharing the labour-intensive processing and canning with Chinese immigrants. As vividly described by historian Rolf Knight, it was not easy work: “They worked amid a Rube Goldberg collection of steam vats, chutes, canning machines, hoses, pipes, steam, clanking transmission belts and other paraphernalia.” Ten-hour days were the norm. When runs were at their peak, shifts were even longer.

The commercial fishing industry became part of the seasonal life for thousands of Aboriginal people. In Makúk, his thorough examination of the labour history of BC’s First Nations, historian John Lutz estimates that a family of four working in the canneries could earn as much in three or four months as a skilled white tradesman over an entire year. Many travelled long distances for the work, camping on their own or housed in company-built cabins. Once the salmon runs were over, they would return to their communities for the winter to engage in a regular round of ceremonial dances, potlatches and renewal of their ancestral ways.

With their well-developed subsistence economies, Indigenous people were attracted to seasonal jobs: fishing, canning, logging and, toward the end of the century, harvesting hops. They sought wages as add-ons rather than as a means of survival. Yet with the fur trade’s diminished importance, First Nations workers were important to the emerging economy of British Columbia. John Lutz concludes, “Coal would not have been mined in the 1840s and 1850s, export sawmills would have been unable to function in the 1860s and 1870s, and canneries would have had neither fishing fleet nor fish processors in the 1870s and 1880s without the widespread participation of aboriginal people.”

In general, the wages Indigenous workers earned were used to enhance their traditions rather than to buy into “the white man’s ways.” Money allowed the accumulation of goods that were then given away at traditional potlatches. But non-Indigenous authorities considered the potlatch an affront to Christian-based materialism and a barrier to assimilation. They moved to ban the practice in the mid-1880s. Until then and for a spell thereafter, Indigenous culture and artisanship flourished. “There was never a time in the history of the Province when the Indians have been so prosperous as during the present year,” wrote Indian superintendent Israel Wood Powell in his annual report for 1882.

It was not to last. In 1881, ten years after BC joined Confederation, Indigenous people were still a majority in the province; twenty years later, they constituted a mere 14.3 percent. Besides the loss of land, the banning of the potlatch and the ravages of disease, a succession of other calamities followed. After the Canadian Pacific Railway was completed in 1885, Indigenous people were crowded out by wave after wave of non-Indigenous settlers, the pell-mell drive for profit and outright discrimination by whites who wanted BC for themselves. In every industry where Aboriginal people had once laboured productively, they found themselves squeezed by new government restrictions on their hunting, fishing and trapping rights, and the desire by employers for year-round workers coupled with growing mechanization.