11. Postwar Politics

When IWA contract talks got underway in 1946, the union’s demands were ambitious, but familiar: a forty-hour week, union security and dues check-off, plus a wage hike of twenty-five cents an hour. This time, however, there was a difference. The union claimed an astonishing eighteen thousand members, and its wartime no-strike policy was gone. When the companies offered an hourly increase of twelve and a half cents, provided the union dropped its other demands, the union wasted little time pussyfooting around. On May 15, 1946, the vital BC forest industry was shut tight by the largest strike the province had ever seen. The prodigious walkout extended from the coast through to the Interior, closing logging and sawmill operations from Vancouver to Port Renfrew to Prince George.

In a surging show of solidarity, non-union employees joined their union co-workers on the picket line. Within a week, thirty-seven thousand woodworkers were off the job. As in the Queen Charlotte Islands dispute, no one scabbed. Even remote logging camps such as Blue River, where no union organizer had set foot, went out. The union had prepared well, with its dynamic Ladies’ Auxiliary playing a key role. Far from a tea and crumpets organization, Auxiliary women bolstered picket lines, staged marches, helped fundraise and solidified support for the union’s demand for a shorter workweek. “I didn’t marry a meal ticket,” said one Auxiliary member, “but that’s what it amounts to if my husband works more than forty hours a week. We just never see our husbands when they work such long hours.” When the City of Vancouver refused permission for a union tag day, the IWA held one anyway, raising buckets of money from a supportive public.

Halfway through the strike, federally appointed arbitrator Gordon Sloan, a chief justice of the BC Supreme Court, handed down his contract recommendations. He proposed a wage increase of fifteen cents an hour, a limited reduction of working hours that nonetheless set the union on the road to a five-day, forty-hour week, and some improvement in dues check-off, though short of a complete union shop. The companies accepted Chief Justice Sloan’s report. The IWA did not. Fearing the provincial government was about to legislate Sloan’s recommendations to end the dispute, the union mounted a mass march on the legislature by three thousand strikers and supporters.

They came by ferry from Vancouver and by car and bus from all over Vancouver Island. Jonnie Rankin was inspired by the sight of scores of women boarding the midnight boat to Victoria. “You know, it was a wonderful thing,” Rankin told interviewer Sara Diamond. “They came from all these mills all over New Westminster and they were just ordinary working girls, and they walked on that boat singing, ‘You Can’t Scare Me, I’m Sticking to the Union,’ and militant, you know. They just lifted the whole thing.”

After bunking overnight in local armouries, the demonstrators were led by a large group of women from the Lake Cowichan chapter of the Ladies’ Auxiliary, carrying signs and banners backing demands for more take-home pay and particularly the forty-hour week. Cheered on by the citizens of Victoria, they marched toward the Parliament Buildings. As union leaders met inside with members of the cabinet, the protesters paraded around, chanting, “25–40 Union Security!” and singing union songs, their voices clearly audible to those within the legislature’s thick walls. But the stirring protest failed to soften the government’s attitude, and the IWA’s first major strike soon came to an unexpected close.

Influenced by complaints from Okanagan fruit growers, who feared their crops would rot because the strike had cut off their supply of wooden shipping crates, the federal government ordered Okanagan mill workers back to work at their old wage rates. At this point, the IWA was beginning to feel some heat, worried the back-to-work order would be extended beyond the Okanagan and sensing some wavering within the membership. On June 20, the union leadership decided to call off the strike and accept Chief Justice Sloan’s recommendations.

Yet the overall results were positive. There were clear gains in the Sloan report, even if they were short of the union’s hopes. The thirty-seven-day strike solidified the IWA’s position as the strongest union in BC. With the addition of ten thousand new recruits who signed up during the strike, the IWA now claimed twenty-eight thousand members. Its militant leadership had shown an ability to take on the might of the province’s major industry. The fifteen-cent pay hike smashed federal wage controls, setting a pattern for other industrial unions both in BC and across the country, and it would not be long before most woodworkers could look forward to weekends without work.

The strike was a watershed event. During all the years BC workers had been fighting for their rights, such a province-wide walkout would have been beyond the wildest dreams of union organizers. Now, it had happened. The strike also convinced the province’s anti-union employers there would be no rolling back of workers’ wartime gains. For the moment, employers focused on opposing labour’s drive for legislation to impose a union shop and dues check-off on all bargaining units. Such measures, the Canadian Manufacturers’ Association told cabinet, would produce a “tyranny of the majority” in violation of an individual’s right to work.

Already up to 29.8 percent of the non-agricultural workforce in 1945, unionization surged even more during the immediate postwar years, fuelled by a booming economy. Toughened by the Depression and six years of war, workers were not content to accept a lesser share of the pie. This time the craft unions, which had lost initiative during their rancorous split with the muscular industrial unions, were in the forefront. Not only did the building trades expand as construction increased across the province, but other unions within the craft union orbit—belonging to the Trades and Labor Congress of Canada—also took off.

The International Pulp and Sulphite Workers regrouped at large pulp and paper mills in Ocean Falls and Powell River, where managers had fired all “left-wingers” and “foreigners” in the mid-1930s. Union membership also rose among teamsters, transit workers and the fishermen’s union. As workers in the public sector began to attach themselves to the labour movement, their organization of choice was also the TLC. The BC Teachers’ Federation brought five thousand members into the congress, the BC Government Employees’ Association four thousand and the National Union of Public Employees, a forerunner of the Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE), another two thousand.

Industrial unions suffered a slight, temporary membership dip, with a decline in coal mining and the province’s once mighty shipbuilding industry. But they lost none of their fight. In the dying days of the war, just before the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, 450 members of the United Steelworkers of America struck American Can, the Vancouver factory that produced all metal containers in the province, in a forceful bid for a union shop. Later in the year, thousands of Crowsnest coal miners staged a month-long wildcat walkout over, of all things, inadequate meat rations. They demanded more fresh meat and an end to rationing of bologna for their lunchtime sandwiches. The baloney brouhaha finally ended when the miners secured concessions from the Wartime Prices and Trade Board.

The next year, just as the IWA had taken on the province’s forest industry, the Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers’ Union went head to head with BC’s obstinate mining companies. Having secured a good agreement for its several thousand members at the Consolidated Mining and Smelting Company’s large smelter and mining operations in Trail and Kimberley, Mine Mill sought industry-wide bargaining for its twelve metal mines in the province. When the companies refused, two thousand Mine Mill members walked out on July 3, 1946, shutting down the province’s metal mines except those run by Consolidated. Chief Justice Sloan, fresh from his similar role in the forestry strike, was quickly appointed as a conciliator. After ten days he quit, declaring that the mining companies’ refusal to bargain as an industry made a settlement impossible. In a blunt message to the mine owners, the chief justice told them, “If 147 lumber operators can sign an agreement, so can you.”

Instead, the companies kept up a steady barrage of propaganda against the union and its spirited leader Harvey Murphy. With regular radio broadcasts, they also raged against BC’s allegedly union-friendly labour legislation. New laws were necessary, proclaimed the Western Miner, “to cope with the rapidly increasing power concentrated in the hands of union leaders … so communists will be deprived of their most potent weapon.” Despite their bluster, the employers’ solidarity shattered first. In mid-October, two copper mines settled with the union, followed shortly afterward by two silver-lead-zinc mines. A month later, the Hedley Mascot gold mine signed a union agreement. The remaining mine operators accepted settlement terms on December 5, and the strike was over. Although wage gains by the union were modest, their members had stuck together and broken the mines’ resistance to any form of industry-wide negotiations.

It was an impressive display of union strength, which only hardened the owners’ determination to see the last of labour minister George Pearson, whom they blamed for creating a climate in which unions could persevere. BC employers began pressuring the shaky ruling coalition to tilt the legislative balance in their favour once more. The fact that company representatives received an advance look at the new Industrial Conciliation and Arbitration Act (Bill 39) while labour was left in the dark showed which way the wind was blowing. Introduced in March 1947, the bill contained two key employer demands: government-supervised votes on all conciliation reports and making unions liable to heavy fines and lawsuits for any activity deemed to be illegal. Rather than quell job action, labour leaders predicted these measures would only lead to more strikes. “Where [the Act] puts one tooth in, it puts in a pair of pliers to yank it out,” said Federation of Labour president Dan O’Brien.

The labour movement’s fight against Bill 39 marked the beginning of a new era in industrial relations. Now that the fight for basic rights such as certification, compulsory collective bargaining and union recognition had largely been won, union energy was increasingly directed against a steady stream of legislation that restricted them in other ways. They found themselves fighting off employer actions in the courts and shoring up structurally to take on the battles ahead. Advances continued, but the struggles were different.

Not long after the war, employers had discovered to their delight that the courts could be just as effective as truncheons for thwarting unions. For the next twenty-five years, police on horseback and the billy club were replaced by the court injunction to keep labour in its place. Injunctions could be obtained against almost any union picketing that kept customers and other workers away from the work site. The vast majority were issued after one-sided hearings on the basis of employer affidavits without any union representation in the courtroom. Not only did these ex parte injunctions tie up resources as unions fought to overturn them, they also led to many trade unionists going to jail for defying them.

The pattern was set in 1946 during a violent strike at the Vancouver Province newspaper. Members of the International Typographical Union struck the paper on June 5 to support ITU members in Winnipeg, whose strike against that city’s two dailies was not going well. Both the Province, then Vancouver’s largest-circulation newspaper, and the Winnipeg Tribune were part of the Southam chain of papers. The union was not above using muscle to try to keep the Province from publishing. Four strikebreakers brought in by the paper were forcibly evicted from the company building across from Victory Square. Others were harassed and manhandled, their hats grabbed and put on display at the front of the Province building with a label “Rats’ Hats.”

When the Province tried to resume publication on July 22, delivery trucks leaving the loading docks were confronted by crowds of union supporters. One vehicle was overturned. Copies of the paper were burned or scattered about surrounding streets. Photos of strikebreakers, including their names and addresses, were published in the ITU’s publication, the Typo Times. Labour forces in the city carried out an intense boycott campaign against the Province. Some news vendors were warned their stands would be overturned if they carried the paper. Other newsstands were picketed. Signs read, “It is easy to help the union printers. Don’t buy the Daily Province.” Many didn’t. Thousands of readers cancelled their subscriptions and turned to the Vancouver Sun, which supplanted the Province as the city’s number-one newspaper.

But the ITU strike led to BC’s first significant court injunction against union activity. After the initial attack on strikebreakers, the company obtained an injunction preventing the union and its supporters from gathering in large numbers, from accessing the Province building and from “watching and besetting” the paper’s premises. In short order, the injunction became a blueprint for the courts, its terms often copied word for word in other far less violent cases where companies applied for relief against picketing. “Watching and besetting,” a term lifted from the Criminal Code, became a key phrase in injunction after injunction. Not long after the Province case, an injunction against striking employees of the Aristocratic Restaurant in Vancouver seemed to outlaw legal and peaceful picketing merely for being effective.

Court injunctions gave employers a powerful new weapon. Since almost all applications were ex parte, with only the employer allowed to present evidence, they were almost never denied. Nor did they have any time limit. Unions had to challenge ex parte injunctions after the fact, when it was often too late to do any good. Worse, anyone disobeying an injunction could be found guilty of contempt of court and sent to jail. When emotions ran high during a bitter strike, complying with an injunction was not always easy, especially when the courts rarely gave any thought to the root causes of a dispute or considered behaviour of the employer. For the first time since the 1930s, labour leaders were finding themselves behind bars.

Dan O’Brien’s prediction that Bill 39 would lead to more rather than fewer strikes proved correct. A few months after its passage, a major flare-up took place in Nanaimo over unionized laundry worker Violet Dewhurst’s decision to book off work to attend a BC Fed convention in Vancouver. When Dewhurst returned, she was fired along with another worker who had taken time off to care for her sick mother. Twenty-eight employees walked out in protest. They had strong backing from the labour movement, which saw the dispute as the first fightback against Bill 39’s prohibition of spontaneous strikes. There were mass pickets and a large parade through the streets of Nanaimo featuring Bill 39 hung in effigy and one-day sympathy strikes by local coal mine and sawmill workers.

Authorities quickly laid charges under the new ICA Act against all twenty-eight strikers, the Nanaimo Laundry Workers’ Union, regional CCL director Dan Radford and the United Mine Workers’ Percy Lawson. This time the courts were sympathetic. Judge Lionel Beevor Potts pointed out that the wildcat walkout had nothing to do with collective bargaining procedures. “It’s a great pity this thing ever arose,” he said, adding the relevant provision in the act was “cumbersome and long drawn out.” Although he found most of the strikers guilty, he fined them a token one dollar each.

A month later, it was the Steelworkers’ turn to defy the legislation, striking five Vancouver-area iron and machinery companies without holding a government-supervised vote. On September 2, 1946, 114 workers, two officials and two union locals were charged with violating the ICA Act. This case also drew withering comments from the judiciary. With charges pending against packinghouse and furniture workers who had also ignored the act, punctuated by a widespread, month-long transit strike and a walkout by Vancouver Island coal miners, the government bowed to growing consensus that its legislation needed to be amended. Legal proceedings came to a halt.

Although the amended ICA Act contained a few changes sought by labour, its overall thrust restricted unions even more than the original. Not only was the hated supervised strike vote retained, the Labour Relations Board (LRB) was given added power to order a membership vote on any “bona fide” settlement offer made by an employer. As well, unions were now more liable to be sued and even decertified for an illegal strike. They also lost their chief ally in the coalition government’s labour minister George Pearson, who made no secret of his opposition to supervised union votes. His departure was cheered by the business community, which had long agitated for someone less sympathetic to labour in the job. In his thorough study on the ICA Act, UBC graduate student Paul Knox observed, “The life work and philosophy of one reformer (Pearson) proved no match for the organized forces of a dominant class.”

The labour movement’s ability to fight the legislation was further compromised by the ongoing internal struggle between communist-led unions and those supporting the CCF. From the beginning, the main labour opposition to Bill 39 had been spearheaded by unions with communist leadership, whose membership numbers gave them control of both the Vancouver Labour Council and the BC Federation of Labour. But most communist leaders, like the IWA’s Harold Pritchett, knew enough not to let their left-wing politics get in the way of representing workers under capitalism. “It would be foolish—and impossible—for us to try and force socialism into Canada, until the people want it,” he told a Vancouver Sun reporter in 1947. In the meantime, Pritchett said, the IWA was “willing to operate within the framework of capitalism … The forest industry means our livelihood … We need it every bit as much as the operators do.”

But the writing was on the wall for communist leaders and their unions, both in BC and the rest of Canada. A Cold War between the western democracies and a newly powerful Soviet Union was being waged on the international stage, rife with fears of homegrown spies and communists. It was a period of witch hunts for alleged “Reds,” blacklists, and purges of organizations where communists were prominent, notably in the labour movement. Anti-communism began earlier and took hold more intensely in the United States. Even before the US’s entry into World War II, communists had been hounded out of many unions. Pritchett himself had felt its sting when he had to resign as international president of the IWA in 1940 after US authorities refused him a visa for speaking at the funeral of a BC communist. In 1947 Republicans and southern Democrats rammed through the odious Taft-Hartley Act, which piled numerous new restrictions on unions including a requirement that all officers take an oath affirming they were not members of the Communist Party.

The Canadian Congress of Labour and the rival Trades and Labor Congress also worked to expel unions with communist influence. In the most singular example, the Canadian government, shipping companies, AFL “roadmen” in Canada and eventually the tlc gave a green light to the US-based Seafarers’ International Union (SIU) to break the storied Canadian Seamen’s Union (CSU). The CSU was an all-Canadian, communist-led union that had organized freighters on the Great Lakes and the country’s extensive fleet of deep-sea vessels. The SIU was led by the notorious Hal Banks, who had served four years in San Quentin prison for forgery and whose connections to the American mob were shrugged off by those who wanted the CSU gone.

When the CSU launched an unprecedented strike against Canadian deep-sea shipping companies in 1949 that tied up ships at ports around the world, Banks used organized thuggery on vessels docked in Canada, including Vancouver, to help break the strike. Strikebreakers were herded through CSU picket lines by SIU goons wielding axe handles, chains and sawed-off shotguns. With the assistance of sweetheart contracts signed behind the backs of the Seamen’s Union, Banks and the SIU soon controlled the waterfront from coast to coast.

TLC president Percy Bengough, who got his trade union start as secretary of the Vancouver Trades and Labor Council at age sixteen, resisted for a time. Complaining to the federal government about AFL interference in Canadian union affairs, Bengough declared, “[We] will accept domination no more readily from Washington than from Moscow.” But once he fell in line, under intense pressure from the AFL’s threat to withdraw its affiliates from the TLC, there was barely a ripple of protest from the non-communist labour movement.

The Canadian Seamen’s Union disappeared, albeit with a reputation as one of Canada’s most inspiring rank-and-file unions. Now that he had cleaned out the CSU, Banks showed no sign of stopping. Under his direction, the SIU began expanding its empire, moving in on other Canadian maritime unions with the same tactics of violence, sweetheart deals and support from the AFL in Washington. Battles took place in Vancouver and other ports across the country. Too late, the TLC realized the SIU medicine was far worse than the cure. Only when the burly Banks went on the lam to the States in the mid-sixties, to escape a criminal charge of assaulting a rival union leader, did an uneasy calm descend on the Canadian waterfront.

After barring eighteen left-wing delegates from attending its 1950 convention, the TLC adopted its own Taft-Hartley-like policy banning communists, members of the Labour Progressive Party “or any person advocating the violent overthrow of our institutions” from holding office in unions affiliated with the TLC. One of the targets was crafty, cigar-smoking communist Jack Phillips, who headed Vancouver Civic Employees’ Union Local 28. The TLC ordered him to resign. Instead, Phillips led the union out of the TLC. Backed by the membership, Local 28 survived an onslaught of legal and raiding challenges by TLC unions before finally joining CUPE as Local 1004 in the late 1960s.

The United Fishermen and Allied Workers’ Union was another target. Amid fending off a raid by the SIU in line with Hal Banks’s determination to organize “everything that floats,” Bengough suspended the fishermen’s union because of its “very definite leaning toward communism.” As with the Vancouver Civic Employees’ Union, members of the UFAWU backed their leadership, flourishing outside the “house of labour,” as the mainstream labour movement called itself, for the next twenty years.

The rival Canadian Congress of Labour was equally eager to purge its communist-led unions. Firm supporters of the CCF, the CCL’s national leaders loathed communists within their ranks, not for their trade unionism but for their willingness to co-operate at times with the federal Liberals, their convention resolutions conforming with the Soviet Union’s view of the world and their resistance to embracing the CCF as Canada’s labour party. Nowhere was the militant Left stronger than in British Columbia, where communist-led unions had played a dominant role organizing the province’s industrial workers. In 1947 the congress appointed the brash thirty-year-old Bill Mahoney of the United Steelworkers of America as its Western director, giving him two years to “clean out the communists.” It took him less than one.

Mahoney scored an early success at the Vancouver Labour Council. He rounded up eligible delegates from every local, no matter how small and obscure, that had mostly shunned the left-wing council. Under his direction, they drew up a slate of non-communist candidates for the council’s twenty-one elected positions and won every one. The triumphant Mahoney next turned his sights on the BC Federation of Labour. He began by dabbling in the internal affairs of its largest affiliate, the IWA, working with its relatively small anti-communist “white bloc” to challenge the supremacy of Pritchett and other officers. This venture failed. Pritchett’s slate trounced the white bloc in union elections, retaining all executive positions and maintaining control of every local but New Westminster.

Then Mahoney was handed an unexpected plum by Mine Mill leader Harvey Murphy. At the time, that union represented almost all BC metal miners, plus several thousand smelter workers in Trail. “[Murphy] was the soul of the union,” remembered lawyer John Molson, who did legal work for the union during its fierce raiding battles with the Steelworkers in the 1960s. “He was all for the worker, and the men loved him. A real straight shooter, a good talker and he could be very funny. I liked him immensely. I would call him a rough diamond.”

Unfortunately for Murphy, his rough side came to the fore at a labour banquet in Victoria in the spring of 1948. Upset over CCL support for the deportation of Mine Mill’s international president Reid Robinson because of his communism, and having had by his own admission too much to drink, Murphy lashed out at CCL officials, ridiculing them as “phonies” and “Red-baiting floozies.” He went further, causing his speech to go down in labour lore as Harvey Murphy’s “Underpants Speech.” Referring bitterly to CCL president Aaron Mosher and secretary Pat Conroy, both hard-line anti-communists, Murphy suggested that if asked to kiss the boss’s arse, their only request would be for the boss to first pull down his underwear.

Mahoney pounced. He immediately laid charges against both Murphy and Pritchett, who had emceed the banquet without censuring his comrade-in-arms. While Pritchett and other Federation officers were merely reprimanded, Murphy was decked with a two-year suspension from all meetings of the Canadian Congress of Labour and its chartered organizations, including the Federation of Labour. Even better for Mahoney’s mission was Mine Mill’s suspension from the CCL over an attack on Mosher in the union newspaper. This cost the communist side twenty-two key voting delegates at the Fed’s forthcoming convention.

After a summer touring the province to round up convention delegates, Mahoney was ready for his coup de grâce. The Fed gathering that September, fought over political attitudes rather than specific trade union issues, turned into one of the most dramatic labour conventions ever. For two days, the two evenly split sides battled it out at the microphones. To paraphrase Abraham Lincoln’s famous statement, never was a house of labour more divided against itself.

Voting was even more intense. Left and right sides fielded full slates for all executive positions. Mahoney, a backroom master, was confident his side had one more vote. So he was stunned when communist Bill Stewart of the Shipyard Workers edged the Steelworkers’ Pen Baskin 66–65 for first vice-president. Positive he had left nothing to chance, Mahoney surmised someone had double-crossed him. For the next ballot, he assigned CCL officer George Home to “assist” the suspected vote-switcher in his vote for second vice-president. Sure enough, this time the same, razor-thin 66–65 tally was in favour of Mahoney’s candidate, Stewart Alsbury. With Mahoney’s men continuing to ride shotgun on the delegate, communist titan Harold Pritchett was toppled from the key post of secretary-treasurer, again by 66–65. When voting ended, Mahoney’s slate had control of the BC Federation of Labour. The communists were vanquished.

In the meantime, Mahoney had continued to zero in on the BC IWA, whose communist leadership was under increasing pressure from the union’s international officers in Portland. Working with the International, Mahoney vigorously played up some sloppy but not fraudulent bookkeeping by the BC District, which showed $150,000 unaccounted for. The district’s representative on the international executive was fired for refusing to take an oath that he wasn’t a communist, and thirty-three of their international convention delegates were refused entry to the United States. BC District leaders felt the walls closing in on them. Fearing trusteeship would be next, they made a fateful decision in the fall of 1948 to break away from the IWA and form their own union, the Woodworkers Industrial Union of Canada (WIUC). Officials quietly moved their assets to secret accounts. Files and office equipment were moved to an equally secret location.

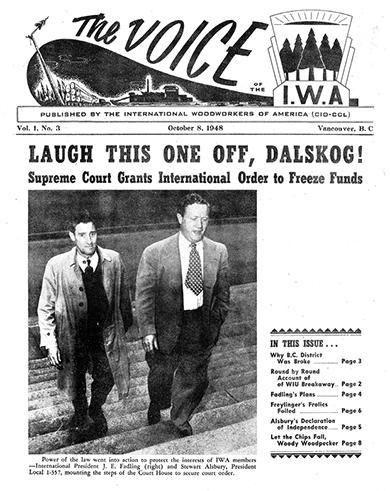

But the white bloc also moved quickly. That same night, with the help of the Sun’s Jack Webster, an ally of Mahoney’s throughout, two union officials worked until dawn to produce their own copy of the union Lumber Worker, which went out in the mail. The next day, international president James Fadling and New Westminster white bloc leader Stewart Alsbury applied to the courts to freeze the IWA’s BC assets. Alsbury was appointed provisional president of District Council No. 1, and the International undertook to secure all its local charters and certifications.

Three weeks later, the new forestry union held its first convention, full of bluster and bravado. “The Woodworkers’ Industrial Union is here to stay,” proclaimed Harold Pritchett, who had privately opposed the breakaway. But legally, certifications remained with the IWA and rare was the company willing to switch to the WIUC. Dues check-off became a serious problem. Whenever the new union did manage to reorganize a workforce and apply for certification, the Labour Relations Board often stalled proceedings long enough to stymie the union’s drive.

The fate of the WIUC seemed to boil down to a critical stand at Iron River, a MacMillan logging camp controlled by the union south of Campbell River. In mid-November, after a flare-up over the firing of two loggers, the WIUC shut down the entire operation. Both sides considered the dispute a key opportunity to prove their mettle. The WIUC went all out to support the wildcat walkout; the IWA tried to break it. On an application from the IWA, the LRB declared the strike illegal, prompting Stewart Alsbury and a few other IWA officers to escort a group of twenty-five IWA loggers in to work across the picket line.

Amid the pre-dawn glare of car headlights, the picketers turned on them. In the resulting mayhem, Alsbury had his ribs broken. Two others were also sent to hospital. The next night, twenty-six provincial police and a gang of 150 men recruited by the IWA—many from south of the border—made sure the loggers got in to work, daring the small band of WIUC picketers to take them on. When the picketers wisely opted to stand aside, the swarm of IWA men burned down their picket shelter instead. Five WIUC picketers were charged with assaulting Alsbury and the others. On the witness stand, Alsbury admitted that the company had invited him to bring loggers into the camp. He also testified that the IWA had enlisted white bloc volunteers to infiltrate WIUC operations on Vancouver Island. Defendant Mike Farkas confessed to beating up Alsbury and throwing him to the ground “because [he] had tried to lead scabs through a picket line.” His cause was not improved by defence witness Danny Holt, who recounted for the court that when Alsbury “yelled for mercy, I told Farkas, ‘Hit him again, Mike.’ And Mike did.”

Unable to maintain the strike, the WIUC picket line came down in April. By then, the union had managed to secure just nine certifications through the slow-moving labour board. The union’s stalwart vice-president, Ernie Dalskog, spent nearly a month behind bars until he complied with a court order to return the IWA’s $130,000 strike fund. As difficulties mounted, leaders of the WIUC realized success was not in the cards. They began to soften their vilification of the IWA, stressing the need once more for “one union in wood.” Less than a year after its bold separation, the WIUC closed its doors.

Bill Mahoney returned to Ontario, where he eventually became Canadian director of the United Steelworkers of America and a major advocate for AFL-CIO unions in Canada. WIUC leaders were blacklisted by the IWA. Pritchett returned to his old trade as a sawyer and shingle weaver, never allowed back into the union he had done so much to build. Ernie Dalskog could find work only as a first-aid man in non-union logging outfits. Still, with the white bloc at the helm, IWA members did not shirk from strikes. Not all produced the benefits that were sought, especially some long, bitter disputes in the Interior and northern BC. But on the coast, centralized bargaining produced good overtime rates, paid statutory holidays, compulsory dues check-off, medical insurance and other benefits, and a healthy fifty-cent raise in the base rate to $1.59 an hour. Other unions continued to look to the IWA to set wage and benefit patterns for BC industrial workers.

Bitterness from the deep political division in the IWA eased over time. Eventually there was appreciation of the communists’ contribution to the union, although its blacklist of so-called “errant members” took fifty years to erase. The move at the 1998 convention was “far, far overdue,” said president Dave Haggard. “They were workers, and they were IWA members, and they helped build this union.” Former BC Communist Party leader Maurice Rush used the occasion to return the original charter of Local 1-85 from Port Alberni, stressing what a mistake the WIUC was. “It did not strengthen workers,” said Rush. “It divided and weakened them in their struggle with the employer.” And some could laugh about it. One veteran of the ill-fated decision with a taste for graveyard humour liked to tell the story about a membership meeting near the end, when WIUC numbers were dwindling. Looking around at all the empty seats, an old Swedish logger observed, “Well, at least we got rid of all those phonies.”

At the national level, the Canadian Congress of Labour kept up its drive against communist-led unions. Although Mine Mill had been allowed back in the CCL after its suspension, higher-ups now wanted the troublesome union expelled for good. This would be a boon to the Steelworkers, who had an eye on the union’s certifications in the mines of BC and metal refineries and nickel smelters of Ontario. At the urging of the congress’s executive council, delegates to the CCL convention in the fall of 1949 voted overwhelmingly to throw them out permanently. The next year, with the expulsion of the United Electrical Workers and the Fur Workers, the CCL’s purge of communist-led unions was complete.

Mine Mill remained a force outside the Canadian Congress of Labour. Attempts by the Steelworkers to raid its large smelter workforce in Trail were rebuffed by a membership that stayed faithful to Mine Mill despite its communist leanings. Most of the union’s mines stayed too. Harvey Murphy also carved a place for himself in left-wing lore by organizing a legendary Paul Robeson concert. The famous American singer had been invited to perform at Mine Mill’s 1952 convention in Vancouver but was denied entry into Canada because of his politics. Murphy invited Robeson to a substitute concert at Peace Arch Park, straddling the border between Canada and the United States. Robeson famously sang from the back of a flatbed truck on the US side to an estimated crowd of ten thousand people on the Canadian side.

Ousting unions simply because their elected leaders took a different view of the world was not a glorious chapter for the labour movement. Few questioned the communists’ commitment to trade unionism. But their ejections played out against the anti-Red hysteria of the Cold War—from which the trade union movement was not immune—and a very real, intense political antagonism between the CCF, backed by a large majority of the country’s labour leaders, and those sympathetic with the Soviet Union. Perhaps, given the highly charged emotions of the times, the fracture was inevitable.