20. War and Peace under the NDP

The volatile Vander Zalm years, which had British Columbians and Canadians across the country shaking their heads over some of the antics that went on, came to an end in 1991. After forty years as a fixture in BC politics, Social Credit soon disappeared, mourned by no one in the trade union movement. Decades of fighting the Socreds’ anti-union policies had unions looking forward to an era of progress and relative harmony under the NDP and the province’s new premier Mike Harcourt, a former activist lawyer and popular mayor of Vancouver.

In the meantime, the face of the labour movement had changed. As public services expanded and private-sector unions saw their membership reduced by workplace automation, free trade and other pressures, public-sector unions were moving to the forefront. Women, who constituted a large part of the public sector, took on an increasingly prominent role. These trends were apparent in a big way ahead of the change in government during the seventeen-day BC Nurses’ Union (BCNU) strike in the summer of 1989.

The tumultuous nurses’ strike rocked the province and permanently changed their union. For years, nurses tended to believe that patient care was too saintly a task to be sullied with demands for more pay. Rather than being rewarded for their dutifulness, however, nurses found their wages falling further and further behind those of other professions. Only when they began to embrace the collective advantages of a union did their employers cough up better pay and improve working conditions. BC nurses began negotiating through their professional association, the Registered Nurses Association, but it was not a satisfying arrangement.

In 1976, the RNABC established a separate Labour Relations Division headed by Nora Paton to bargain formally for the province’s nurses. Separation became complete five years later when two hundred nurses congregated at the Empress Hotel in Victoria to form the BC Nurses’ Union. Although conditions and wages subsequently improved, the restraint programs of successive Social Credit governments had kept their pay levels below nurses in other provinces. As bargaining for a new contract covering 17,500 hospital nurses got under way in 1989, the membership’s mood was militant, as shown by a lofty 94 percent strike vote. Beset by a nursing shortage they believed was caused by inadequate wages, nurses were determined to boost rates to a level commensurate with bottom-line industrial workers.

“We have been undervalued for years, and we believe our time has come,” said BCNU president Pat Savage. The union called for a 33 percent wage increase over two years. Job action began in late May with a ban on cleaning, housekeeping and other non-nursing duties. It took two more weeks for the hospitals’ Health Labour Relations Association (HLRA) to table its first wage offer: an increase of 18 percent over three years. Spurning the proposal, nurses began walking off the job on June 14. Within days, their strike had spread to all public hospitals in the province. Hospital workers belonging to the Hospital Employees’ Union and the paraprofessional Health Sciences Association respected the nurses’ picket lines.

While essential services were provided by all three unions, the strike was the most extensive labour disruption to hit BC hospitals. Elective surgeries were cancelled, patients were discharged where possible, and managers were forced to prepare meals, make beds and do the laundry. HEU members officially joined the picket lines on June 22 with their own strike. At the HEU’s strike rally, where secretary-business manager Sean O’Flynn vowed his members would “wipe the smiles off management’s face,” Pat Savage told the many nurses in the crowd, “We are making progress in turning up the heat. So keep it up!”

Four days later, BCNU negotiators announced they had a tentative agreement providing a wage increase of 29.5 percent over three years. The deal did not go over well. Their determination and expectations rising with every day on the picket line, many nurses reacted to the news with anger. The next day, more than seven hundred crowded into a large Vancouver hotel room to demand answers from Pat Savage, the only member of the bargaining committee to show up. The BCNU president was booed and heckled. In the heat of the moment, Savage agreed to change the recommendation to accept the pact, a decision she rescinded in the calm of the following day.

Two days later, 150 nurses stormed a union executive meeting, tearing up copies of Pat Savage’s press release and insisting on renewed negotiations to get a better contract. “I was in the office when they stormed in,” said Fernie executive member Andy Wiebe. “I thought they were going to rip the office apart. It was pretty awesome, let me tell you. Members wanted to have their voices heard and they did.” One embittered nurse explained, “This strike was to get nursing up to a professional level, beyond the blue-collar worker. Well, this offer isn’t going to do it.”

Two nurses from Vancouver General Hospital emerged as leaders of the growing dissident movement: Debra McPherson and Bernadette Stringer. With strong membership support, the two set out to defeat the tentative contract. In addition to unhappiness over the terms themselves, nurses also felt the wishes of the membership had been given short shrift by the BCNU’s paid staff, whom they accused of doling out little information and running the union as a fiefdom. “Their refusal to talk to the membership was disrespectful,” recalled McPherson. “We got disrespect from the employer. We didn’t need it from our union.”

The nurses’ picket lines came down on July 1 and the ratification fight began. At a large, enthusiastic “no” meeting, attendees donated $5,300 to send Stringer and McPherson on a province-wide tour to urge nurses to vote down the deal. It was a throwback to the days of grassroots organizing. Billeted in members’ homes, the duo spoke at impromptu membership meetings in the Okanagan, the Kootenays, northern BC and on Vancouver Island. All told, they travelled sixteen hundred kilometres by car, listening to nurses’ concerns and explaining why they should vote no. BCNU president Pat Savage also toured the province but found it tough slogging.

With a 77 percent turnout, nurses voted 65 percent to reject their union’s recommended agreement. As much as anything, the success of the protest movement was a matter of membership empowerment. Nurses had wanted more. They felt their leaders hadn’t listened to them. But there now seemed no way for the parties to settle the dispute on their own. The parties agreed to binding arbitration by Vince Ready. The labour fixer decided on a two-year contract with a total wage increase of 20.9 percent, a slight hike in the annual pay package from the original three-year agreement.

The membership may not have been pleased with the result, but the strike and rejection campaign were pivotal events for the union. No longer were members willing to accept a union that appeared to be controlled by its paid staff with little input from the rank and file. Kathy Bonitz, a Burnaby Hospital shop steward, said the “no” camp demonstrated you couldn’t ignore the membership. “Since then, BCNU has become much more of a member-driven, grassroots organization. And that’s a very good thing.” The strike also led to a fundamental change in leadership. Debra McPherson used her experience in the “no” campaign to run successfully for president of the nurses’ union a year later. She wound up heading the BCNU for a total of eighteen years.

Despite the NDP victory in 1991 and the glow from Harcourt’s “Let’s boogie!” invitation on election night, there was no immediate difference for public-sector unions at the bargaining table. For twenty-nine thousand frustrated members of the Hospital Employees’ Union, the same employers’ attitude that had earlier provoked such anger among BC nurses carried on. After twelve months without a contract, the hospitals’ wage offer remained stuck at 2 percent a year, well below other public-sector settlements. At the same time, Social Credit’s prescription of bed closures, layoffs and contracting out continued as if nothing had changed.

Faced with growing cost pressures and a large deficit inherited from the Socreds, the Harcourt government seemed loathe to intervene. NDP health minister Elizabeth Cull was booed when she spoke to HEU protesters outside the legislature. Their mood was not improved when the HLRA’s confrontational president Gordon Austin headed off job action by applying to the detested Industrial Relations Council, which had not yet been replaced, for a special mediator.

Renewed bargaining improved the employer’s offer, but there was no provision for a key union demand, pay equity for women. By April 23 a series of small rotating strikes had turned into picket lines at selected hospital departments across the province. Finally the government stepped in. After meeting with the union, labour minister Moe Sihota appointed former LRB chair Don Munroe as a special conciliator. Munroe recommended a three-year contract containing improved wage increases, pay equity adjustments and rate comparability with the BCGEU by October 1, 1994, all of which led to a large raise for the union’s lower-paid women workers. Members voted overwhelmingly in favour.

In the meantime, the NDP was grappling with recommendations by the Royal Commission on Health Care and Costs established by Social Credit in 1989. The commission’s well-received report concluded the health-care system was too centred on costly acute care in hospitals. Both care and the bottom line would be enhanced if there were fewer hospital beds and more resources siphoned into long-term care, community health centres and home care. But cutting acute-care beds would also mean the loss of thousands of union jobs. Early in 1993, assistant deputy health minister Peter Cameron was assigned to see what could be worked out with the HEU, the BC Nurses’ Union and the Health Sciences Association.

Cameron showed the unions how many jobs were likely to disappear under the government’s ambitious goal to reduce patient days in acute-care hospitals. His charts convinced the unions to buy in and reopen their existing collective agreements. After forty-four gruelling days of negotiations, including some sessions lasting well into the night, the parties produced an agreement that was unparalleled in scope. Covering more than forty-five thousand health-care workers, it recognized their job security while paving the way for slashing up to 10 percent of the hospital workforce.

The Health Labour Accord attracted national attention, hailed by public-sector unions across the country as a landmark social contract in government-employee relations. Under the accord, unions accepted the government’s plan to eliminate two thousand acute-care beds with an estimated loss of as many as forty-eight hundred jobs. Most were members of the Hospital Employees’ Union. In return for their co-operation, the unions won guarantees of job security, retraining, a role in hospital decision-making and a reduction in the workweek from 37.5 to 36 hours a week with no loss of pay. Employees losing their hospital jobs were to be offered equivalent positions elsewhere in the system. It was hoped many replacement jobs would be found in non-hospital facilities, where the government aimed to put more and more of its dollars. Early-retirement incentives and attrition were also part of the package.

“It means our people can move with the switch from acute care to community care,” said Carmella Allevato, secretary-business manager of the HEU. Predictably, the opposition, editorial writers, business leaders and the hospitals themselves assailed the package as a “sweetheart deal” with the unions. Wild costing figures were tossed about, none of which stood up to scrutiny. The HLRA failed to ratify the package, provoking impromptu, one-hour study sessions by health-care unions at five BC hospitals. Finally, after the government threw some extra money into the hospitals’ pot, the accord went ahead.

It was tested right off the bat when the government decided to close the aging, three-hundred-bed Shaughnessy Hospital in Vancouver. Twelve hundred employees shifted seamlessly along with specific Shaughnessy services to other locations. But 439 employees saw their positions disappear altogether. The accord’s newly established Health Labour Adjustment Agency managed to find jobs for all who were willing to accept them within the health-care system. Three hundred managers were not so fortunate. With no union contract, they were simply let go. Overall, the Shaughnessy closure saved the government nearly $40 million a year, with no loss of union jobs.

Similar results occurred wherever there were bed closures. The government was able to reduce costs, few health-care employees lost their jobs, and a difficult transition was managed without serious bumps and bruises. Originally expected to be temporary, the accord was so effective that its core feature, the Employment Security Agreement, was written permanently into the health unions’ collective agreements in 1996.

Replacing Vander Zalm’s ideologically based Industrial Relations Reform Act (Bill 19), a centrepiece of the party’s election campaign, was another early task of BC’s first NDP government in sixteen years. Emulating the course of its NDP predecessor, the Harcourt government appointed a troika of experts to recommend measures for a new labour code. Instead of Bill King’s “three wise men,” however, they became known as “the three amigos”: mediator Vince Ready and experienced labour lawyers John Baigent and Tom Roper. Pulling together and fine-tuning proposals from a nine-member committee, they produced a 125-page report that would form the basis of the new labour code.

The IRC was scrapped in favour of a reconfigured Labour Relations Board. The right to secondary picketing, though still subject to LRB approval, was restored, as was the legality of “hot” declarations. Automatic union certifications, based on a majority of the workforce signing union cards, were back. And BC became the second province in Canada, after Quebec, to proclaim a so-called anti-scab law, banning the use of strikebreakers during a strike or lockout. Strikebreakers do nothing but prolong labour disputes and induce picket-line violence, said labour minister Moe Sihota.

Ending mandatory union certification votes was a boon to organizing. During the eight years Social Credit had required a vote every time a union applied to represent a bargaining unit, the average number of annual certifications fell by 45 percent. With the return of sign-up certifications, which eliminated the opportunity for employers to intimidate workers and campaign against the union in the run-up to a vote, newly organized workers more than doubled to an average of 8,762 a year.

However, Sihota disappointed the labour movement when he declined to follow the amigos’ recommendation to bring in sectoral bargaining. That would have allowed unions to win a few certifications in a hard-to-organize industry such as retail, negotiate a master agreement and then use that contract to gradually claim other certifications until most of the industry was unionized. Small business would have “gone berserk,” Sihota explained. “We had a mandate to bring in a new labour code … that made it easier to unionize. [But] we made a conscious decision not to swing the pendulum [too far] and have another government come in and reverse it.”

The NDP also raised the minimum wage to $7 an hour, the highest in the country, and further enhanced working conditions with a new Employment Standards Act. For the first time, farm workers, live-in nannies, taxi drivers, artists, security guards, fishermen and newspaper carriers were brought under the legislation. And as the Barrett government had done, the Harcourt government brought in a fair-wages act to ensure that union rates, or close to them, were paid on all government projects.

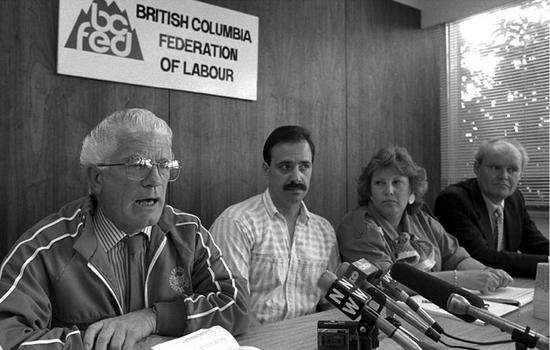

Despite the NDP’s many moves to improve matters for workers and the labour movement, there were still disputes with unions who felt the government should do more. Yet whenever it did anything perceived as friendly to labour, the government faced a chorus of attacks, denounced for “caving in” to unions. BC Fed president Ken Georgetti was termed the “nineteenth cabinet minister,” as if working people having access to government was a bad thing. “We don’t have our way all the time, despite what most of the media claims,” Georgetti said. “But we do know that when the government makes a decision, our views [are] considered. And that is a significant breakthrough.”

As it was, Georgetti was irked that two large, union-backed developments he vigorously promoted were killed by the government. The ambitious Bamberton housing project north of Victoria and a controversial convention centre, hotel and casino development on the Vancouver waterfront were to be financed largely by union pension funds and create thousands of jobs. But hostile community pressure prompted a thumbs-down from the NDP government. Teachers also found themselves in conflict. Flexing their new right to strike acquired under Bill Vander Zalm, over thirty BCTF locals hit the bricks from 1988 to 1994, winning good wage increases and in most cases, limits on class size.

But the government seemed to grow tired of seeing classrooms behind picket lines. In 1993, the province legislated an end to protracted strikes in Surrey and Vancouver, and the following year put a stop to local-by-local negotiations that teachers found so beneficial. The Public Education Labour Relations Act imposed province-wide negotiations for all major issues, severely limiting what could be negotiated at local bargaining tables. There would be no more strikes in individual school districts. Teachers were incensed by the change, but there was no rolling it back.

The Harcourt government did manage a compromise with public-sector unions, which had threatened to disrupt the NDP’s 1995 convention over a proposed 1.2 percent cap on wage increases. The unions agreed to accept restraint, provided that money was channelled to lower-paid workers and that the government reviewed public-sector wages. “We have acknowledged that there is just so much money to go around,” said BCGEU president John Shields.

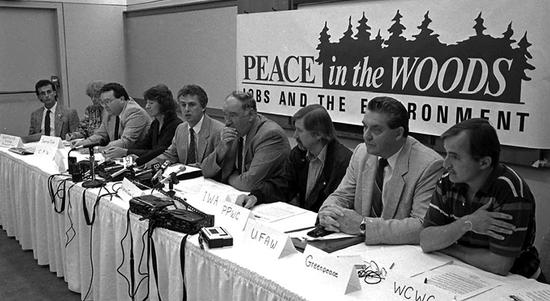

It sometimes seemed as if the Harcourt government spent almost all its energy trying to steer a middle course through a minefield of problems left behind by Social Credit. No issue sparked more attention, controversy and emotion than the government’s attempt to resolve growing demands by environmentalists and First Nations for the preservation of Vancouver Island’s remaining old-growth rainforests. For the labour movement and particularly the IWA, whose members stood to lose good-paying union jobs for every stand of timber saved from the chainsaw, this was a frustrating matter beyond the realm of collective bargaining. This time, no indomitable strike could stem the tide, as the union had against contracting out in 1986.

The IWA was paying the price for a rapacious forest industry that had had its way for years under Social Credit, clear-cutting, damaging sensitive watersheds and skimping on reforestation. With BC dubbed “Brazil of the North,” the anti-logging campaign was on. The previous decade had already witnessed some high-profile skirmishes. First Nations and green activists had halted logging on Meares Island near Tofino and Lyell Island on Haida Gwaii. More protests preserved half the Carmanah Valley on Vancouver Island for parkland. Conscious of the growing clamour, the NDP made sustainable development a key plank in its election campaign, vowing to end valley-to-valley conflict by striking a balance between preserving jobs and preserving the best of the province’s precious rainforests. But a temporary truce between the factions did not last, and confrontations resumed.

They came to a head in “the War in the Woods” at Clayoquot Sound, 260,000 hectares of mostly unharvested, pristine rainforest on the west coast of Vancouver Island. In April 1993, the government enraged environmentalists by leaving up to two-thirds of the lush area open to selective logging, albeit under the most restrictive regulations ever imposed on the forest industry. In what was termed the largest act of mass civil disobedience in Canadian history, environmental groups marshalled waves of protesters that summer to blockade the main logging road, in defiance of a court injunction. More than eight hundred individuals, from grandmothers to kids, were arrested and charged with criminal contempt of court. Many were jailed for up to sixty days.

With the War in the Woods garnering global attention amid worrisome boycotts of BC-cut wood, a new set of rules were applied to logging in Clayoquot Sound that were light years from the haphazard cutting of the past. Environmentalists were pleased. But the IWA estimated that the new cutting restrictions and park preservation would cost its members at least fourteen hundred jobs. Feeling like “the meat in the sandwich” between environmentalists, First Nations’ land claims and the government, twenty thousand angry woodworkers and their supporters marched on Victoria in a noisy demonstration to bring attention to their pending unemployment.

The NDP was sympathetic. Established as a Crown corporation to retrain and find jobs for laid-off woodworkers and funded by a bump in stumpage fees, Forest Renewal BC provided some employment relief. Later however, a Jobs and Timber Accord, trumpeted as a “social contract for the woods,” foundered with the dramatic revenue loss from the collapse of the Asian economy. IWA frustration boiled over when two Greenpeace vessels docked in Vancouver Harbour on their way up the coast to more logging protests. Turning the tables, the union kept the ships tied up for a week with a blockade and picket line of its own. “The issue is [Greenpeace] imposing its will on our members and their families,” said IWA president Dave Haggard.

By the time the NDP government was defeated in 2001, it was recognized worldwide for its environmental record, preserving millions of hectares of wilderness, doubling parkland in the province and installing a long-awaited Forest Practices Code with real teeth. Still, the many union jobs lost in the process would never return. It wasn’t easy coping with so many conflicting interests, acknowledged former environment minister Moe Sihota. “You have to deal with the reality of jobs, the reality of wood running out, the reality of communities that have always voted for you up in arms, and the reality of others that have looked to you—environmentalists, Natives—up in arms as well.”

These years also saw the beginning of new labour awareness of Indigenous issues. Unions strongly supported the controversial 1998 Nisga’a Treaty, the first BC treaty signed in a hundred years. That same year, a comprehensive task force on First Nations education by the BCTF led to the hiring of a full-time Indigenous staff person and a reaching out to Indigenous educators to improve graduation rates and the teaching of Indigenous history. The BCGEU succeeded in organizing employees of two First Nations governments, although opposition from some Indigenous leaders prompted the union to set up an Aboriginal council to try to foster understanding.

(Such moves have continued in the 2000s. The BC Federation of Labour meets with Indigenous organizations and has actively promoted reconciliation over the tragedies of residential schools and missing and murdered Indigenous women. Some unions have included Indigenous customs within their contracts, including a right to seasonal leave without losing seniority and easing seniority to provide more apprenticeships. And midway through 2017, the Labourers’ International Union, Canada’s largest construction union, with eight thousand BC members, inked a pact with the Assembly of First Nations to encourage training and employment of Indigenous workers on big projects. “The potential is incredible,” said union vice-president Joseph Mancinelli.)

Tension between unions and the NDP did not magically disappear under Harcourt’s successor, Glen Clark, who pulled off an unexpected come-from-behind election win in 1996. Clark, a former union organizer, was helped immeasurably by strong support from organized labour. Unions were particularly offended by Liberal leader Gordon Campbell’s vow to scrap the anti-scab law, and encouraged by Clark’s direct appeal to blue-collar workers. The United Food and Commercial Workers, for example, sent letters reminding each of its twenty-five thousand members about Campbell’s scab promise. On election day, the union organized carpools to ensure all members at its many organized supermarkets got to the polls, the kind of initiative considered critical to the party’s narrow victory.

Ironically, a few months later the UFCW professed unhappiness over Glen Clark’s perceived role in ending the union’s six-week strike against the province’s supermarket chains. The BCGEU took out ads lambasting the government for trying to make small reductions in the civil service to balance the budget. In 1999, unionized community social services workers staged a hard-fought eleven-week strike to bring their wages up to the level of community health workers. And many teachers objected when BCTF president Kit Krieger and his executive reached a controversial deal directly with the premier’s office that provided class size limits and class composition standards in a master provincial agreement. In return, teachers accepted the government’s wage restraint pattern of 0, 0 and 2 percent over three years. At the next BCTF convention, arguing that Krieger was too close to the government, David Chudnovsky from the militant Surrey local ran against him for president and won.

The fall of 1994 had also seen a throwback to the old days of labour defiance and punishment in Port Alberni. Trouble flared when MacMillan Bloedel brought in a non-union contractor to work on an addition to its Alberni pulp mill, work that had always been done by BC’s unionized building trades. Hundreds of union members converged on the site to take a stand. For several months, mass pickets barred entry to the site, including a violent confrontation when the contractor tried to drive through. Court injunctions eventually did the trick and the way was cleared. But many chose arrest over stepping aside. Tears streaming down his face, pipefitter Ron Gehring told the Vancouver Sun’s Val Casselton, “I’m proud of what I’m doing. I can look [my family] in the face and tell them that.” All told, one hundred picketers were convicted of contempt of court and sentenced to fourteen days in jail or electronic monitoring. Cells filled up, and authorities ran out of monitoring bracelets. Minus a bracelet, former building trades president Bill Zander was told not to leave home for fourteen days. He complied. “I did a lot of gardening,” Zander said.

Overall, however, despite an up-and-down economy and ongoing difficulties for unions in the private sector, labour did well under the NDP. Extending basic health and safety standards at last to the province’s toiling agricultural workers was a real breakthrough. Under Glen Clark the NDP went further, setting up a hands-on Agricultural Compliance Team (ACT). With representatives from employment standards, the WCB, the motor vehicle branch and federal agencies, the ACT took a proactive approach to inspections and enforcement, providing the best protection BC farm workers had ever had. Changes and standards that unions had sought for years were now in place, and labour’s voice was heard at the cabinet table.

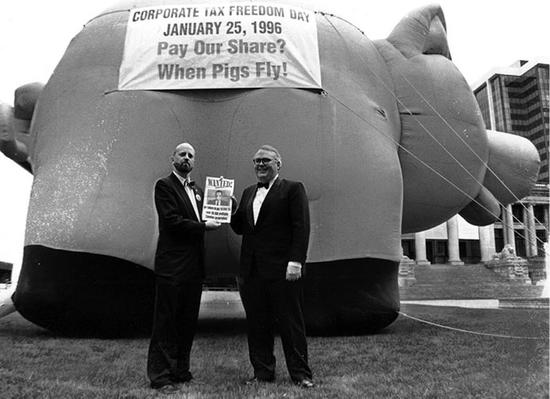

There was even opportunity for humour. Chuckles abounded over the BC Federation of Labour’s effective and funny “Corporate Tax Freedom Day,” a stunt dreamed up by the Fed’s communications director Bill Tieleman to counter the Fraser Institute’s vaunted Tax Freedom Day. The latter was the dubious date, usually in June, on which the right-wing think-tank claimed an average Canadian family had earned enough money to pay all its myriad taxes for the year. The BC Fed proclaimed “Corporate Tax Freedom Day” in early January to illustrate how little tax corporations paid. The share of federal revenue from corporate taxes had declined from 21.5 percent in 1960 to just 7.5 percent in 1990. The first Corporate Tax Freedom Day was staged on the top floor of a downtown hotel on January 27, 1993. Disguised labour types celebrated in tuxedos and fancy dresses. The highlight was a “Race to the Trough” featuring ten battery-operated, oinking toy pigs emblazoned with logos of Canada’s major corporations. The TV cameras loved it. When a fuming Fraser Institute denounced the well-covered event, the Federation was overjoyed. But far more serious matters lay ahead as the NDP’s ten years in office came to a shattering close with a 77–2 shellacking at the hands of Gordon Campbell’s Liberals in the spring election of 2001.