19. Expo 86 and a New Premier

Bill Bennett’s third term continued to be difficult terrain for unions. While his government never quite found the gumption to bring in right-to-work legislation to end both the union and closed shop, the concept had more than a few adherents within the Social Credit caucus. They particularly detested the near monopoly held by the powerful building trade unions on all major construction projects in the province. These unions, whose origins went back to the nineteenth century, had weathered twenty years of W.A.C. Bennett and were more than holding their own under his son Bill.

But in 1982, J.C. Kerkhoff and Sons, a little-known construction company from Chilliwack, shocked the building trades by securing a $14 million contract to build the new provincial courthouse in Kamloops. It was the largest public project awarded to a non-union contractor in BC. Despite union protests and considerable skepticism that the company had the skill and expertise to do the job, the courthouse was finished ahead of time and under budget. At the official opening, local MLA and ardent right-to-work advocate Claude Richmond could not resist crowing, “People were abusive and told me point blank it couldn’t be done. But Kerkhoff showed that non-union contractors can do anything done by the union sector, do it faster and for less money.”

The driving force behind the company was chippy thirty-seven-year-old Bill Kerkhoff. With the help of like-minded concrete supplier Ewald Rempel, Kerkhoff displayed a single-mindedness in blazing a trail for non-union contractors that was underestimated by the building trades. He had hands-on support from many in government. Claude Richmond made that clear at the opening of the courthouse: “There’s no question that Mr. Kerkhoff and I were in the trenches on this for quite a while.”

In the spring of 1984, Kerkhoff took his crusade to Vancouver, emerging with the contract to build the final two-thirds of a large, luxury condominium project known as Pennyfarthing in False Creek. Enraged to find Kerkhoff on a site where they had worked two weeks earlier, the unions could not let this pass. “It was like a red flag in the face of the building trades,” summed up Local 115 of the Operation Engineers in its account. A union blockade went up. The site became a daily magnet for hundreds of desperate, unemployed construction workers haunted by the lack of available jobs during BC’s grim recession. Close to downtown and the popular Granville Island market, and a short stroll from the city’s two newspapers, Pennyfarthing was big news.

Tantalizingly visible just across the waters of False Creek was another reason for the union stand. There sat the vast site for Expo 86, an ambitious world’s fair scheduled to welcome visitors in little more than two years. Pennyfarthing was a warning by the building trades of their determination and capacity to fight to ensure the fair’s massive amount of construction would be the exclusive preserve of union contractors. “We’ve got to convince Bennett that we can screw up Expo,” BC and Yukon Building Trades Council president Roy Gautier told a heated rally at Pennyfarthing. Stoked by such talk, protesters confronted anyone who challenged their illegal blockade.

On March 19, Kerkhoff and Ewald Rempel decided to do just that. When Rempel purposefully drove up to the site, his Ford Ranger was quickly surrounded, rocked back and forth, pelted with a foul-smelling material no one wanted to ask too much about, and its tires were slashed. A truck loaded with lumber was similarly attacked and disabled. A week later, Kerkhoff had a court injunction allowing unimpeded access to Pennyfarthing. “We didn’t want to get six months into the contract and have all this happen,” he gloated. “So we sent someone in right at the beginning to provoke a confrontation.” The strategy worked. Already hit with a $30,000 fine by the courts, the unions’ month-long blockade came down.

But the building trades had served notice of the chaos that could erupt over any attempt to allow non-union contractors a share of the construction jewel across the water. Expo 86 had ballooned into an ambitious $800 million venture planned on 175 acres of industrial land laced by sawmills, railway tracks and a Victorian-era barrel factory. It was a lot of construction, and the fair had to be finished on time. Gautier and other building trades leaders were adamant that Expo would be an all-union site or not get built.

Notwithstanding the Kamloops courthouse, only the building trades had the numbers and range of skills essential for a big job. Proud and militant, the building trades also knew how to undermine a project. If the wrong person was assigned a certain task, if there was a slight bending of a safety rule, if there was even a single non-union tradesman on site, work would stop. With that kind of clout, how could Expo risk work stoppages that might imperil the fair opening on time? Nevertheless, the building trades were willing to sign a no-strike pact, as they had with W.A.C. Bennett for his big dam projects in the 1950s and 1960s, on condition that they received all the work.

Gautier was discussing such a pact as early as 1982 with his Expo counterpart Jimmy Pattison, the brash business dynamo from East Vancouver who had agreed to serve as president of Expo 86 for a dollar a year. But their best of intentions went awry with the post-election ascendancy of anti-union hawks in the Bennett government. The new government appointee to the Expo board was none other than Claude Richmond, still relishing his success against the building trades in the Kamloops courthouse skirmish. Bennett made it clear that Expo would be an open construction site. Contracts would be awarded to the lowest bidder regardless of union status. Bennett hailed non-union firms as the free market at work, “a gale of competition in a previously insulated environment.” In a pointed reference to Pennyfarthing, the premier told British Columbians that “the front-line mentality must be replaced by the bottom-line mentality.” He gave Pattison ten days to reach a deal with Gautier and the building trades. After that, Pattison was to recommend whether or not Expo 86 should be cancelled.

The prospect of Expo 86 not going ahead brought a wave of public pressure down on Gautier. But the tall, taciturn, resolute Scotsman had a powerful weapon in the form of the construction unions’ long-established non-affiliation clauses. These gave the trades the right to refuse to work beside any construction worker not belonging to the BC and Yukon Building Trades Council. Gautier said they would be willing to forego their non-affiliation clauses, but only if non-union contractors were obligated to pay a “fair wage” that would cut into their ability to win contracts by shortchanging their workers.

Trying to set that “fair wage” turned into the most excruciating and ultimately frustrating experience in the building trades’ long history. Time and again, Gautier and Pattison reached a deal, only to have it jettisoned by the Expo board or higher up by the ideologically driven government. It happened twice just during the short ten days Bennett had given Gautier and Pattison to forge an agreement.

With no pact in place, Pattison advised the premier to stop the fair. The risk of labour disruption was too great. Bennett ignored the recommendation, albeit insisting he still wanted a deal. That didn’t stop the cabinet from nixing yet another agreement, providing a minimum rate of just over $19 an hour—about $4 an hour less than the union rate and $5 an hour more than what non-union contractors generally paid. At a time when the construction industry was riddled with 50 percent unemployment, the government seemed unconcerned that desperate workers were willing to work for almost anything that would provide more than an unemployment insurance cheque did.

On May 8, the government introduced significant amendments to the labour code. In addition to further restrictions on secondary picketing and enhancing the ability of employers to resist unionization, the changes administered a blow to the solar plexus of the building trades and their critical non-affiliation clauses. The government gave itself power to declare “special economic development projects” like Expo where non-affiliation clauses would simply not apply.

At the end of May 1984, Kerkhoff won his first Expo contract, his bid just $45,000 lower than the nearest union bid. When the Chilliwack contractor turned up, the building trades walked out. The crisis produced still more meetings between the dogged Gautier and Pattison, who by then might have been joined at the hip with all the hours they spent together seeking something, anything, that would pass government muster. Proposed “fair wage” rates, including a whimsical suggestion by Gautier of $19.86 an hour, bounced around like a ping-pong ball. Every time, the government or Expo said no.

Finally, the two managed a deal brokered by deputy labour minister Graham Leslie that almost everyone, even Kerkhoff, thought would fly. But Claude Richmond railed against it, and that was that. Thunderstruck, Gautier called this latest double-cross “absolutely incredible,” a sign he’d been negotiating, he said, “in a sea of dishonesty and duplicity.” The Vancouver Sun sympathized with his exasperation. “Every time he makes a concession to cut a deal on the use of non-union contractors, the Expo directors throw it back in his face,” the newspaper wrote. “Are they mad, or just following orders from someone who is?”

The final showdown came in August when a second non-union contract was awarded. Marabella Pacific Enterprises, a cobbled-together enterprise with Ewald Rempel as half-owner, won the contract with a $4.7 million bid that was only $20,000 less than the bid of a unionized company. The moment Marabella equipment moved in, out went the building trades once again. Bennett didn’t wait for the labour board to rule on the walkout. The government quickly exerted its new power to proclaim Expo an “economic development zone” carved into fourteen union and non-union sites. Further, the premier warned that contracts would be taken away from any construction firm whose workers were off the job for more than three days. The hammer had come down with all the powers of law and government. Short of defying the courts and having their treasuries drained, there was little the once mighty construction unions could do.

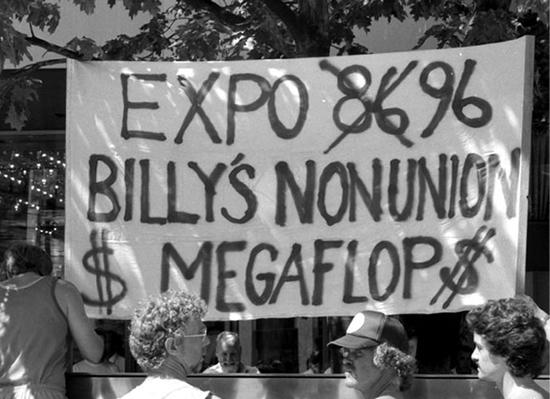

In addition to myriad compromises by Roy Gautier, the building trades had fought back with every weapon they had. But their lanky leader had been whittled down like a piece of wood. Although the vast majority of construction at the fair subsequently wound up in union hands, Expo was a watershed event that changed the nature of the BC construction industry for good. Over the next six months, the share of non-union construction in BC went from 37 percent to 54 percent. The figures would fluctuate from year to year, but the days when a job in major construction meant joining one of the building trades were at an end.

The building trades did get in a late lick at Expo’s non-union contractors. A number of them had taken advantage of unemployed workers’ desperation by stiffing them on overtime and paying less than the $15.25 minimum wage eventually established by the government. The carpenters’ union took up their cause, running large newspaper ads calling on shortchanged workers to contact the union. Scores did. Many said they had no idea of the mandated rate, since Expo had refused to post it at construction sites and failed to monitor compliance. Some were paid as little as $7 an hour.

As these horror stories came to light, the Employment Standards Branch assigned ten full-time officers to investigate. By the end of February 1986, non-union contractors had been forced to pay out more than $110,000 in back wages. Diedrich Gerbrand was one who benefited. An experienced carpenter, he’d been paid $8 an hour with no overtime. “But what could I do? I’ve got four kids to feed. I’d been off work for quite a while,” he said. So much for fairness in Bill Bennett’s “new economic reality.”

The fight with the construction unions was Bennett’s last as premier. Shortly after Expo 86 opened, on time and on budget, “the tough guy” resigned after a stormy eleven years as premier, his lingering unpopularity from the 1983 confrontation with Operation Solidarity making re-election uncertain at best. His surprise successor was former Social Credit cabinet minister Bill Vander Zalm, the perpetually smiling gardening guru from Surrey. Parlaying his photogenic charisma and effective glad-handing into a “faaaaan-tastic” election victory over the NDP’s bland new leader Bob Skelly, Vander Zalm promised an end to the bitter divisions of the Bill Bennett era. It was not to be, as foreshadowed by something that happened even before voting day.

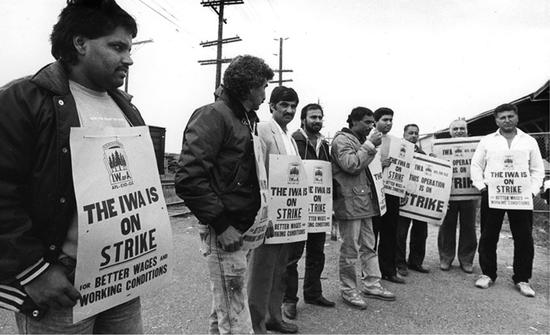

The flags were set by the podium with care, in hopes that the premier soon would be there. It was early evening, October 3, 1986, and Bill Vander Zalm was about to get a lesson in labour relations. The new premier had taken a highly publicized break from the current election campaign, convinced he was about to settle one of BC’s most challenging and costliest strikes, a showdown between the IWA, its largest private-sector union, and the coastal forest industry, its largest employer. The dispute was then into its third month. Aides scurried about, affixing the BC seal to a hotel room podium and setting up a pair of BC flags to adorn what was expected to be the grand announcement. Reporters sat waiting before the vacant podium. The hours ticked by. No premier. Well past midnight, a bewildered, bleary-eyed Vander Zalm emerged briefly from shuttling between the dug-in parties, musing to reporters, “Strange business, this negotiating …” At 3 a.m. the premier, who seemed to think his legendary charm was all that was needed for peace to break out between two sides at odds for months, gave up. The seal and flags were packed away, and Vander Zalm scuttled back to the campaign trail, humiliated.

Only later did it emerge just how ineffectual the premier’s intervention had been. In his autobiography, IWA leader Jack Munro recounted an early-morning plea by Vander Zalm for union negotiators to be more flexible. The blunt Munro said he was tired of the premier’s “yapping.” He suggested that Vander Zalm tell the industry to move. “But Jack,” said Vander Zalm, “they won’t move.” Exhausted, exasperated and feeling he was being used as an election ploy, Munro snapped, “You’re the fucking premier. Act like one!”

The dispute ran two more months. When it was over, twenty thousand woodworkers had waged the most prolonged shutdown ever experienced by BC’s coastal forest industry. And it had nothing to do with money. It was all about jobs. For four and a half months, an angry Jack Munro and his unyielding membership fought what at times seemed an unwinnable strike for protection against the contracting out of IWA jobs. Munro’s bitterness over the companies’ attitudes ruptured his long understanding and quasi-friendship with his counterpart on the industry side of the negotiating table, Forest Industrial Relations (FIR) president Keith Bennett. The two didn’t speak to each other for another year.

At their first bargaining session, FIR tabled four pages of contract concessions. For his part, Munro was single-minded: there would be no agreement without effective restrictions on contracting out. As companies opted to hire cheaper contract crews for work formerly performed by union members, too many IWA jobs were “going down the tubes,” said Munro. In early July 1987 he removed all IWA issues from the table but two: pensions and contracting out. The fight was now clear, and it soon moved to war. On July 25, IWA members walked out at logging and sawmill operations up and down the coast.

Going on strike in the midst of an industry downturn on a non-monetary issue was not for the faint of heart. As a skilled negotiator, Munro was under no illusion of the difficulties. Rather than shutting everyone down, he reached out to operators agreeable to the unions’ contracting-out demands. To FIR’s annoyance, the industry found itself being whipsawed. When the union signed deals with employers in the northern Interior and four coastal companies—Doman, Whonnock, Nova Lumber and Westar—FIR responded with large newspaper ads accusing the IWA of “economic terrorism.”

Less than two months in, however, the IWA’s strike fund was down to $17. Munro asked the labour movement for help. The response was overwhelming. The CLC provided an immediate loan of $1 million by taking out a mortgage on its own building in Ottawa. “What good is a building when people are getting their asses kicked on the streets?” said CLC president Shirley Carr. The BCGEU also handed over $1 million. CUPE and Local 40, the Bartenders Union, coughed up big bucks too. Union dock workers, often at political odds with Munro, voted to personally donate the equivalent of an hour’s pay each. The ninety-nine-member projectionists’ union threw in $50,000. Small individual cheques came in from everywhere. IWA members still working contributed $5 a day. The shutdown continued.

In mid-September, the IWA got another boost. A non-binding report by BC Supreme Court Justice Henry Hutcheon concluded that the union was justified in its contracting-out concerns. Although FIR rejected his report, it shored up union morale and public opinion. As Vander Zalm discovered, however, there was no bend in the industry’s willingness to ride out the dispute as long as it could. Mediator Don Munroe tried and failed to end the impasse, now stretching into November. The IWA seemed to have nowhere to go.

But one more settlement attempt, this one by former IWA officer Stuart Hodgson and forestry expert Peter Pearse, tipped the balance. Their recommendations were so bad, so far below the IWA’s realm of settlement that it rejuvenated the membership. After more than four months on strike and suffering financially, their vote to reject the report was higher than their original strike vote. The strike took on new life. Mass pickets defied court injunctions at a non-union logging operation. Munro delivered a barnburner speech at the BC Fed convention. The growing anger prompted the influential Truck Loggers’ Association to reach an understanding with the fired-up IWA and pressure the large coastal forest firms to do the same. It worked. FIR agreed to a letter of understanding that the companies would not contract out IWA jobs, pending the findings of a one-person commission by lawyer Ken McKenzie. Based on McKenzie’s report, the two sides reached a deal on contracting out that was acceptable to the IWA. The union also won pension improvements, including the right of long-time workers to retire at sixty, and a small wage increase.

With few cards to play other than their solidarity and fortitude, twenty thousand woodworkers had taken on the most powerful industry in BC for seventeen tough weeks on a matter of job security, not money, and scored a victory. Looking back, Munro pointed to the assistance from other trade unions. “We were able to borrow $8 million basically on our word,” he said. “I don’t think anything like that has ever happened in Canada.” By assessing all members $5 a day, the union was able to pay back every cent in less than four months.

Three years after many had questioned his trade union bona fides over the Kelowna Accord, Jack Munro demonstrated what had always been true. In the BC labour movement, he was a moderate, believing in compromise whenever possible. But when left with no option but to fight, the province’s most high-profile trade unionist proved a working-class warrior. The next year IWA members in Canada joined the labour movement’s growing nationalization. They left their international union in an amicable separation to form an all-Canadian union, IWA-Canada.

On the eve of Social Credit’s re-election, Bill Vander Zalm had mused to the Rotary Club of Vancouver how great it would be if labour and management could sit down and work things out without strikes and lockouts. The premier committed himself to a tripartite forum for ongoing consultation among business, labour and government. “We’ll show there is a better way.” Like many politicians before and after him, once in office, Vander Zalm’s shiny election promises became yesterday’s news.

Vander Zalm was even duplicitous about his vow to seek industrial relations harmony. While rookie labour minister Lyall Hanson and his deputy Graham Leslie dutifully set out to consult with labour, management and the public about possible changes to the labour code, Vander Zalm convened a cabal of lawyers and others to draw up legislation for his own reforms. Hanson knew nothing about it. Still piqued by the failure of his ham-fisted intervention in the IWA strike and obsessed with union rights that didn’t allow organized businesses to do whatever they wanted, the premier was planning yet another Social Credit assault on the province’s trade unions.

In the meantime, with a strong push from Leslie and private arbitrator Joe Weiler, labour and business leaders were behind closed doors coming close to a milepost agreement to set aside their differences and work together to improve the province’s investment climate. Leading labour’s side of the talks was the new president of the BC Federation of Labour, Ken Georgetti. He had run unopposed in late 1986 to replace the battle-weary Art Kube. The thirty-four-year-old Georgetti had spent most of his working life as a pipefitter at the Cominco smelter in Trail. There, he rose to prominence as president of the Steelworkers’ large Local 480 during a spirited but ultimately unsuccessful raid by Steel’s archrival CAIMAW.

The mustachioed Georgetti was young, energetic and moderate, with little time for table-thumping rhetoric. He would preside over the Fed for the next thirteen years before making the leap to leader of the Canadian Labour Congress, a post he held for another fifteen years. Eager to put an early stamp on his provincial leadership, Georgetti was receptive to the idea of a structured forum of consultation and consensus with business. After a series of meetings, Georgetti, Graham Leslie, Business Council president Jim Matkin and Darcy Rezac of the Vancouver Board of Trade tentatively agreed to set up the Pacific Institute of Public Policy, with a goal of working together to improve business and labour practices. The Canadian Labour Market and Productivity Centre promised $1 million in funding.

This hard-won spirit of good will and co-operation was soon blown out of the water. At the beginning of April 1987, Vander Zalm brought in Bill 19, one of the most comprehensive, one-sided pieces of legislation to hit the province’s trade unions. The new Industrial Relations Act replaced the NDP government’s groundbreaking Labour Code, much of which had remained intact under Bill Bennett. Unlike Bennett’s restraint measures aimed at the public sector, Bill 19 was directed primarily at BC’s private-sector unions.

The Labour Relations Board was sent packing, replaced by an all-powerful Industrial Relations Council (IRC) headed by Ed Peck. The former overseer of Bennett’s wage-control program was given broad powers to intervene in any strike or lockout deemed to be affecting “the public interest” or a threat to the economy; impose lengthy cooling-off periods; order essential services maintained even in private-sector strikes; and institute binding arbitration. These were unprecedented powers for an unelected individual, taking Peck from “wage czar” to “labour czar.” (Subsequent amendments transferred some of these powers to the cabinet, but the essential arbitrariness of the legislation remained unchanged.)

“Hot” declarations, secondary picketing and most union successorship rights were done away with. The building trades’ vital non-affiliation clauses were restricted. Unionized companies were allowed to set up non-union branches, a practice known as “double-breasting.” Employers would now be able to order votes on their “final offers,” they were given more freedom to campaign against union organizing drives directly in the workplace and they could sue unions in the courts without prior permission from the labour board, now the IRC. The government’s public hearings and vaunted consultations had been nothing but a sham.

Reaction was swift. Georgetti called the package “a flagrant insult.” Jack Munro thundered, “It’s just insanity.” New NDP leader Mike Harcourt said the Socreds had moved labour relations back fifty years. Key employers also objected to the bill, criticizing its interference in free collective bargaining. Graham Leslie, the government’s respected deputy labour minister with a long history of bargaining for municipalities, soon resigned. In a startling open letter to the premier, he denounced the legislation as an attempt to de-unionize the province and predicted confrontation ahead. “The bill was … the product of too few and too narrow minds,” he told Vander Zalm through the pages of the Province.

At an overflow union meeting in Vancouver, Fed secretary-treasurer Cliff Andstein said many in the room might have to go to jail for defying the legislation. To tumultuous applause, he declared, “If that’s the case, so be it.” As its first protest, labour withdrew from all joint government-business-union initiatives,including apprenticeship programs, a drug and alcohol task force and the fledgling Pacific Institute of Public Policy, dashing what Leslie called a “once-in-a-lifetime opportunity” to improve BC’s adversarial industrial relations. Next there were threats to boycott the IRC, swelling protest rallies and a work-to-rule campaign, plus a ban on overtime set to begin May 21. On the eve of the overtime ban, ten thousand trade unionists gathered in Vancouver’s Robson Square to hear a call to arms. Georgetti announced that members had voted 91.6 percent to back the Federation’s action plan, which included the possibility of a general strike. “Bill 19 goes, or we fight,” said the BC Fed leader.

The Robson Square rally included many teachers, who had already been out on the picket lines to protest another piece of anti-labour legislation. Introduced at the same time as Bill 19, Bill 20 gave teachers full bargaining rights, with the right to strike, for the first time. But the package also included some poison pills. Attesting to Vander Zalm’s conviction that the BCTF did not represent the views of rank-and-file teachers, the bill ended the organization’s compulsory membership and dues check-off. Teachers in each individual district would now have to reorganize and apply for certification. Principals and vice-principals were unilaterally removed from the union. Teacher certification, discipline and professional development were taken from the teachers and given to a new, multilateral College of Teachers.

The BCTF wasted little time striking back. On April 28, 1987, the vast majority of the province’s twenty-eight thousand teachers ignored Vander Zalm’s threats and stayed away from work on a one-day strike. Under the leadership of Elsie McMurphy, teachers continued their protest with an instruction-only campaign, withdrawing from all extracurricular activities for the rest of the school year and into the fall. The BCTF was also fully supportive of the Federation of Labour’s action plan, even if that meant more time off the job.

The day after the Federation’s defiant rally, Georgetti and Andstein spent an astounding nine hours closeted with Vander Zalm and Lyall Hanson going through Bill 19 clause by clause, spelling out their objections. Afterward, Georgetti told the media, “We did all the talking. [Vander Zalm] did all the listening.” A few days later, Hanson tabled forty-eight amendments to Bill 19. Although some provisions were softened, the thrust of the legislation remained. “This is the final package,” insisted Vander Zalm. The next day, accusing the premier of choosing confrontation over co-operation, Georgetti declared a one-day general strike by all organized labour in BC on Monday, June 1.

The Fed’s careful preparation and pent-up union anger produced a historic walkout. More than a quarter of a million workers in every corner of the province stayed home. Ferries, trains and buses didn’t run. Mills and mines were shut down. Construction sites and newspaper presses were stilled. All public services including schools were closed. Non-Fed affiliates such as the Teamsters and unions in the Confederation of Canadian Unions went out too. It was, summarized CAIMAW leader Jess Succamore, “an unprecedented demonstration of solidarity within the BC labour movement.”

In response, the government seemed to lose its collective marbles. Attorney General Brian Smith went to court seeking an injunction to prevent future illegal walkouts, which were characterized in overblown language as an attempt to resist “legislative change, showing Her Majesty has been misled or mistaken in her measures, [and] pointing out errors in the government of the province.” The Vancouver Sun retorted that while “Her Majesty” was safe, it was democracy that was in trouble. Georgetti, McMurphy and eight other union leaders were cited for conspiring to advocate the use of force “as a means of accomplishing a governmental change.” This followed the Criminal Code definition of sedition, prompting one of those named to hide in the closet when he heard a knock at the door.

The overreaction to the peaceful one-day protest was ridiculed everywhere and strongly criticized in the media. The Province splashed the word Sedition! all over its tabloid front page, adding in an editorial that BC was threatening to turn into “an unnerving version of [apartheid] South Africa.” The BC Supreme Court wasted little time dismissing the government’s legal action.

After the June 1 blowout, the labour movement focused its attention on boycotting the Industrial Relations Council. Seeking amendments that would forestall the boycott, Vander Zalm’s key aide David Poole met secretly with Georgetti and Andstein. Although they came close, they couldn’t close the deal. Bill 19 became law after the longest debate on a single bill in legislative history. The labour boycott was on. The protest was not as complete as labour’s shunning of the Mediation Commission nearly twenty years earlier. Unions still had to use the IRC for such matters as certifications, strike votes and fighting employer applications. Although it was far less active than the former Labour Relations Board, the council was able to struggle along until consigned to the trash bin by the new NDP government.

Despite failing to head off Bill 19, labour’s strong opposition dealt the first real body blow to a premier who was presiding over an increasingly disastrous, chaotic administration. As for the teachers, they demonstrated just how little Vander Zalm knew about the depth of their support for the BCTF. They rejoined the organization in massive numbers in every district in the province. Not only did they get their union back, they now had local bargaining and the right to strike.

Vander Zalm’s gospel-like adherence to untrammelled free enterprise carried over into the public sector as well. Out of the blue, the government privatized the province’s bridge and maintenance system. For-profit, private companies were invited to bid for contracts in twenty-eight districts, leaving thousands of government employees facing an uncertain future with no union protection. An innovative bid by the BC Government Employees’ Union to take over the entire system and run it on a non-profit basis was dismissed by the government. Although diligent organizing eventually brought most of the former highways employees back under the union’s umbrella, the process awakened BCGEU leaders to the need to be more than a government employees’ union. Governments were downsizing. Services were being contracted out and bargaining units fragmented. The union responded with a commitment to reach out to workers beyond the direct arm of the provincial government, wherever they were providing services, including the private sector.

The shift meant altering the union’s long-established component bargaining structure, designed for a single employer—the government—and there was strong membership resistance. The matter was thrashed out at the union’s two-day convention in 1989. Debate was long and passionate, stretching into the evening on both days. When the final gavel sounded at 8 p.m. on day two, four hours past adjournment time, delegates had narrowly voted down several proposed component mergers and president John Shields had barely retained his job. But these, as Shields pointed out, were details. With a few changes, the union’s course was set.

To better reflect its growing non-government membership base, in 1993 the union changed its name to the BC Government and Service Employees’ Union, while retaining its BCGEU acronym. By 2016, the union had over seventy thousand members—only twenty-seven thousand of them employed directly by the government—and 550 separate bargaining units. A quarter of the membership worked in BC’s health sector. Another ten thousand were employed in community-based social services. Others worked in credit unions, casinos, community colleges and hotels. Two years earlier, social services worker Stephanie Smith had become the union’s first woman president. She was also its first elected leader to have not worked directly for government.

As the turbulent decade of the 1980s drew to a close, labour found itself fighting another adversary—free trade. In the 1988 federal election, unions poured all the resources they could muster to campaign against the Canada-US Free Trade Agreement. They feared huge job losses to low-wage areas of the United States and an inevitable lowering of their own wages and benefits. But a massive propaganda blitz by Canadian business in the final two weeks helped Brian Mulroney’s pro–free trade Progressive Conservative government romp home with a reduced but comfortable majority. The pact came into effect on New Year’s Day, 1989. Five years later, Canada signed on to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), a new free trade pact that included Mexico.

Although some sectors did better, the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives estimated that Canada lost 334,000 manufacturing jobs over the first six years of free trade, while the income gap between rich and poor widened significantly. In BC, free trade signalled a distinct shift away from highly paid industrial jobs, where unionization was high, to the service sector, where it was low.

Free trade also contributed to the decimation of the unionized BC fishing industry. The United Fishermen and Allied Workers’ Union had parlayed a 1980s boom to negotiate record fish prices and solid contracts for cannery workers, including clauses to alleviate the impact of technological change. In the meantime, set off by the Prince Rupert Co-op’s purchase of Alaska-caught herring roe for processing in Canada, US companies challenged Canada’s ban on the export of its own unprocessed fish. A General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) ruling in late 1987 ordered an end to the restriction, threatening BC coastal cannery jobs. Despite a vigorous campaign by the UFAWU, including a one-day shutdown of the fishing industry, the GATT decision became part of the US-Canada free trade deal.

Cancelling plans for new fish plants, companies used the ruling to demand sweeping concessions from the union. In the summer of 1989, the UFAWU took a stand. Declaring “a free trade strike,” union fishermen tied up for what UFAWU president Jack Nichol called a “historic confrontation to protect Canadian resources, fish prices, working conditions and jobs.” Angry members intercepted trucks crammed with unprocessed, non-union-caught fish as they headed across the border toward American fish plants, and vigilant picket squads did their best to block non-union fishermen. After sixteen days, the union won a concession-free contract for shore workers and fishermen, which included a pension plan still providing benefits today. But they could not escape their fate. With free trade allowing raw fish to move freely across both borders, BC fishermen lost their clout. Within a few years, minimum pricing agreements disappeared and processing switched increasingly to US plants, where wages and benefits were lower. Free trade had done its job.