16. Inflation for the Nation

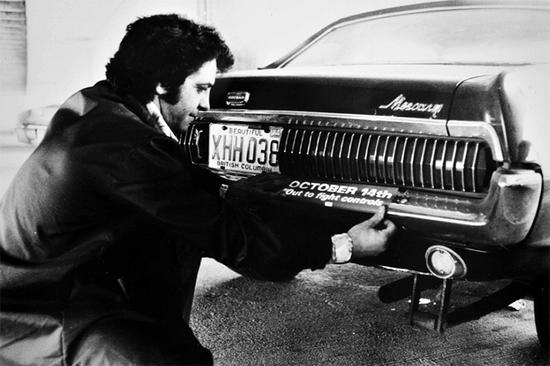

As they awaited their fate under Social Credit, BC unions had more pressing concerns. On Thanksgiving, October 14, 1975, fretting over cascading inflation and soaring wage increases, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau announced Canada’s first peacetime wage controls. Although prices were also to be controlled, wages were the chief target. Over the next three years, pay raises were to be limited to 8, 6 and 4 percent, with an annual upward adjustment of 2 percent allowed for productivity and catch-up. After two years of generous increases, workers were now handcuffed to a third-party tribunal, the Anti-Inflation Board (AIB). The heaviest government intervention in the economy since the end of World War II, controls were aimed directly at unions and their members. It was far easier to limit wage increases than prices. Adding to the sense of betrayal was Trudeau’s strong opposition during the 1974 election to the very wage controls he was now imposing. His anti-wage-control stance had drawn working-class NDP votes from across the country and catapulted the Liberals into a majority.

In BC, the program had an immediate impact on workers hit by the NDP’s back-to-work legislation. The IWA had escaped controls by the skin of their teeth, accepting the $1.55/hour wage increase already on the table, plus a few modest improvements, just days before the program was announced. But the pulp unions were trapped. In an ironic twist of fate, however, after scorning the IWA throughout the summer’s troubles, they were saved by its fortuitous settlement. The AIB exempted the two pulp unions from controls based on their historic wage relationship with the IWA. They were thus able to secure the same increase as the IWA, amounting to 28 percent over two years, well over wage guidelines. Supermarket workers were not so lucky. Wage controls forced them to accept a settlement that was significantly less than what they had been offered before they went on strike.

Union leaders were livid at the program. Even Joe Morris, the mild-mannered president of the Canadian Labour Congress, was roused to fury. At a meeting with NDP premiers Allan Blakeney of Saskatchewan and Ed Schreyer of Manitoba, who signed on to the federal program, Morris became so upset that he “literally chased them from the room, prepared to physically assault them,” former CLC research and legislative director Ron Lang disclosed in 2010. “I have never seen him so angry.” On another occasion, Morris was heard shouting behind closed doors, “This is one goddamned law I am prepared to disobey no matter what the costs!” His outrage was widely shared. A labour war chest of close to half a million dollars was quickly raised to fight controls, Why Me? buttons were ubiquitous and information seminars were held across the country. Unions were advised to negotiate as if controls did not exist. At the CLC convention in May of 1976, delegates voted overwhelmingly to endorse a plan of action that included a first in the arsenal of the national labour movement: a general strike or strikes “when and if necessary.”

In spite of all the fist-pumping vows from union leaders to defy controls, the major confrontation took place far from their podiums in the isolated community of Kitimat, home of the giant Alcan smelter in northwest BC. Although company towns had been part of BC’s resource-based economy since Robert Dunsmuir stumbled on the rich Wellington coal seam in 1869, none was quite like Kitimat. Hacked out of the rugged wilderness in the traditional territory of the Haisla, it was where Alcan had masterminded what was then North America’s largest private construction project. When Prince Philip poured the first ingot in 1953, thousands of construction workers, many of them Portuguese newcomers to Canada, had built a huge hydro dam, a power plant, a lengthy network of transmission towers, a deep-sea terminal, the world’s second-largest aluminum smelter and a townsite. For their instant town, Alcan hired a renowned urban designer to create a model community of happy, contented workers.

Twenty-three years later, those high hopes were in disarray. In the words of newspaper columnist Allan Fotheringham, Kitimat had become “a blueprint without a heart.” Unhappiness had been rife for some time. Fed up with their unsuccessful three-month strike in 1970 and union discipline meted out to some members by the United Steelworkers of America, smelter workers bolted from Steel to form their own union. The vote in favour of the Canadian Association of Smelter and Allied Workers was an overwhelming 1,112–305. On-the-job dissatisfaction, punctuated by class division, was also on the rise. Workers complained of arrogant treatment from company managers, many of whom lived in a more exclusive part of town. Their mood was further soured by the Anti-Inflation Board’s decision to hold their recent two-year contract to federal wage guidelines, saddling them with a wage increase of 15.4 percent while other workers won exemptions—most notably those at the nearby Eurocan pulp mill with their 28 percent pay hike.

On June 3, 1976, simmering discontent erupted into a full-scale revolt. When union electricians and welders walked off the job in a grievance dispute, they were soon joined by almost all of the union’s eighteen hundred members. It was the beginning of an intense wildcat strike that echoed across the country. At a heated meeting that night, union members voted 60 percent to continue their strike, rejecting an executive recommendation to return to work. They rallied behind a demand to reopen their contract. CASAW president Peter Burton spelled it out. The main cause of the wildcat strike, he said, was “Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau … and his rotten Anti-Inflation Board.” It was a fight against wage controls.

The strike became an all-out siege of the smelter. Workers barricaded the only road to the plant with boulders, logs and a high plywood fence. Hemmed inside were four hundred non-union personnel, struggling to keep the pot lines operating to avoid a multi-million-dollar restart if they went cold. In sweltering conditions, they toiled six hours on and six hours off, sleeping where they could on couches and rubber mats. Food and supplies arrived by helicopter and seaplane. After three difficult days, Alcan flew in two hundred supervisory reinforcements from the company’s smelter in Arvida, Quebec, which had been shut down by a legal strike.

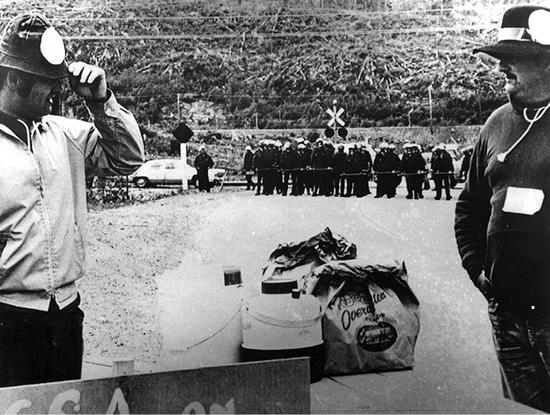

The Alcan workers ignored a cease-and-desist order by the BC Labour Relations Board. On June 8, the board upped the ante by filing its order with the BC Supreme Court. This made strikers liable to contempt-of-court charges, carrying the possibility of large fines and even imprisonment for staying out. On the picket line, amid a festive air of feasting, footballs and Frisbees, the mood remained defiant. “We just want what’s ours,” said one worker. An older employee said company attitudes had hardened. “In the past, it was a pleasure to work. Now, we’re just like a number and a dollar sign.” CASAW repeated its call for Alcan to reopen their collective agreement and support an application to the AIB for a wage adjustment. That, Alcan reaffirmed, was a non-starter.

That evening, at a massive steam bath of a union meeting, the contempt-of-court threat only toughened resistance. More than 60 percent opposed another “strong” executive recommendation to return to work, the highest percentage so far. Earlier that afternoon, meanwhile, sombre news had come from inside the smelter. Kevin Rooney, a thirty-five-year-old reduction development engineer, father of two and unused to pot line work, died of a heart attack after completing his six-hour shift.

By then the RCMP had sent in superintendent Gordon Dalton to oversee restoration of law and order. Tension swept the community, heightened by throngs of media waiting for what seemed an inevitable showdown between workers and police. But Dalton was cut from different timber than the Mounties who had busted so many picket lines in the past. He stayed his hand, hoping to get the two sides to resolve matters voluntarily. On a visit to the picket line, he warned strikers they were forcing an “extremely dangerous” confrontation. Careful not to choose sides, Dalton said he wasn’t concerned by defiance of the courts, but by their blockade of the highway. That was a criminal offence and a matter for police. “This is going to create many problems,” he told them. “You are going to be the loser, the plant is going to be the loser and the community is going to be the loser.”

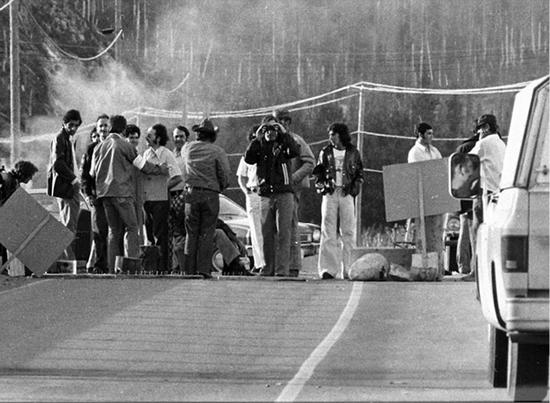

Neither side moved. Burton said union members understood the consequences of their ongoing resistance. “But they have stated five times in the last eight days that they don’t feel they are getting justice under the regime of Alcan and [AIB chair] Jean-Luc Pepin.” When picketers refused to allow company personnel returning from Kevin Rooney’s funeral back into the smelter, police action seemed inevitable. That Friday night, hundreds of workers congregated along the road leading to the barricade. Portuguese strikers turned the occasion into a community gathering. They picnicked, drank wine, sang and waited to be arrested. Scores of vehicles were parked helter-skelter in the middle of the highway to make police manoeuvres as difficult as possible. By midnight, with no sign of the cops, almost everyone had packed up and gone home.

The raid came at dawn, signalled by a stream of headlights cutting through the morning mist. In a long line of cars and buses, the police arrived in force. Wearing visored helmets, beating a steady tattoo with their long riot sticks, 150 Mounties advanced toward the union line. About thirty groggy picketers waited for them. When Superintendent Dalton asked the group to come forward to be arrested “or we will come to you,” they quietly complied. In short order the strikers, including Burton and national union president Bob Feltis, were bundled onto a bus and driven off to jail. A company front-end loader shunted aside the logs, boulders and plywood barrier that had blocked the road for the past ten days. The siege of the smelter was over.

But that was not the end of the strike. Three hours after the blockade came down, eight workers from Alcan’s strikebound Arvida smelter in Quebec set up their own picket line. CASAW members refused to cross, while news of the arrests aroused an outburst of pent-up emotion. Hundreds surged onto the smelter highway. A car that tried to get through was jostled and turned back. The head of the Kitimat RCMP detachment was pushed into a ditch by the wife of one of the strikers, who told him, “Now, you will remember a Portuguese woman.” Speaking from the back of a pickup truck, union executive member Wiho Papenbrock managed to calm the crowd, but hard feelings persisted, particularly toward members who had returned to work; there were fist fights, slashed tires, parking lot confrontations and threats.

Still, the strike lost much of its oomph. Now that Alcan controlled the road, more members began going to work. On Friday, June 18, the LRB ruled the Arvida picket line was also illegal, and it came down. Later that night, trouble flared anew on the road to the smelter. CASAW leaders were told to stay away. Short-lived barricades went up, bottles were thrown and a foreman’s windshield was smashed. Police convoys patrolled the road all night to maintain an uneasy peace. But it was a last gasp. Two days later, a quiet crowd voted on ending the strike. With no further options, half still opted to keep fighting. The count was tied, 374–374. As chair of the meeting, Peter Burton cast the deciding vote to return, after seventeen days of the most determined challenge in the land to the federal government’s wage controls.

Alcan moved swiftly to punish the strikers. Thirty were fired, seventy-four suspended from one to twelve weeks. However, in a ruling that confounded Alcan officials, the firings were subsequently overturned and suspensions reduced by LRB vice-chairman John Baigent. Not only did the company not have “clean hands” in the dispute, Baigent concluded that a discharge or lengthy suspension in a community like Kitimat, with little other viable employment, was “qualitatively different from that same discipline in another setting. In company towns, a job is more a way of life than it is in the more populous southern part of the province.”

The company also failed in its attempt to charge a dozen of the strike ringleaders with contempt of court. BC Supreme Court Justice Henry Hutcheon dismissed the case on the grounds that by the time Alcan filed the charges, the strike had ended and the back-to-work order was immaterial. “The courts should not be used as a means of punishing those who disobey orders of the Labour Relations Board,” Justice Hutcheon said. His judgment showed just how far industrial relations had travelled in the three years since the NDP ended ex parte court injunctions, which regularly put union leaders in jail. Even the thirty workers arrested on the picket line got off, after the presiding judge threw out the first case against Peter Burton for lack of evidence on his public mischief charge. Only in the company’s suit for damages was a price exacted, although CASAW managed to negotiate Alcan’s original $1.3 million claim down to a still onerous $135,000.

Years later in a union history, smelter worker Brent Morrison looked back on CASAW’s stand with pride. “It’s quite a big deal when you go on a wildcat strike for three and a half weeks with one of the largest corporations in the world,” he said. “They don’t like you going on strike in the best of times, the little working man being able to head out and just stop a big company’s production. You can imagine how big a deal it was for a wildcat strike.”

Beyond statements of public support and donations from some individual unions, the mainstream labour movement did not rally behind the Alcan workers’ wage-control fight. CASAW was an independent Canadian union that had broken away from a house of labour affiliate. Instead, the CLC and BC Federation of Labour geared up for their own protest. Plans were set in motion for a one-day general strike on the first anniversary of wage controls: October 14, 1976.

This was new territory for the labour movement and for Canada. Editorial writers, business leaders and most politicians reacted with predictable hysteria. Outspoken Vancouver Liberal MP Simma Holt topped them all, suggesting the proposed strike was tantamount to treason. Opinion polls found most Canadians felt the CLC was acting irresponsibly. Many predicted the protest would be a flop. Undeterred, labour leaders continued to organize and plan for their wage-control D-Day. In BC, labour got a big boost on the eve of the strike when LRB chairman Paul Weiler sent shockwaves through government and the employer community by rejecting their application to have the walkout declared illegal. Weiler concluded that the planned action was political and not designed to improve wages and working conditions. Therefore, it did not meet the definition of a strike under the province’s labour code.

As October 14 dawned west of the Rockies, wheels of production in the province ground to a halt. The public sector was quiet too. Nearly two hundred thousand BC workers answered the call to strike. The forest industry went down. So did the mines and the waterfront. Buses and ferries didn’t run. Garbage piled up for a day, and phones went unanswered in government offices. Normally humming construction sites were silent. No presses printed the Vancouver Sun and Province, though the Fed granted dispensation to their reporters so the day would not be covered by non-union employees. Downtown Vancouver streets had never been so deserted on a weekday. The walkout was capped by a march and boisterous downtown rally attended by more than six thousand good-humoured workers.

Overall, an estimated million workers took the day off to protest, with BC reporting the highest participation rate in the country. To the surprise of many, the twenty-four-hour national general strike—the first in Canadian history—was a resounding success from Victoria to St. John’s. Although labour leaders vowed to continue the struggle, this was the last arrow in their quiver. If anything, the strike’s impressive show of strength had served as an outlet for labour anger. Once it was over, spirit to keep fighting ebbed. After running its three-year course, wage controls died a quiet, natural death.

BC unions were also grappling with the return of Social Credit. But first they had to go through a bruising internal brawl over the direction of the BC Federation of Labour. Len Guy’s leadership and harsh criticism of the NDP government had divided the Fed. Moderate leaders like IWA leader Jack Munro blamed Guy for contributing to the NDP’s defeat. They wanted closer ties with the party, whereas Guy and his supporters embraced what they referred to as “the trade union position.” That meant functioning independently of the NDP, putting union interests ahead of party interests. In the background was Munro’s continued anger over the 1975 pulp unions’ strike and their decision to picket IWA sawmills. Both actions had been backed by Guy and the Fed. The duel played out on the floor of the Federation’s annual convention in November 1976.

On one side were large unions such as the IWA, BCGEU, CUPE and the Steelworkers. On the other side, supporting Len Guy, were the building trades and most of the Federation’s many mid-sized and smaller affiliates that didn’t have the clout of big unions and were more reliant on the Fed. Guy had fired the first public shot at a CUPE convention that summer. Without naming Munro or his union, Guy attacked “some unions and union leaders” for weakening labour by “siding with politicians against the trade union movement. They insist we should try to resist attack only with kid gloves behind closed doors.”

The factions fought it out with gusto at the convention. Anti-Guy forces threw their weight behind Art Kube, the CLC’s effective but relatively low-profile BC education director, who challenged Guy for the Federation’s top job. Most unions sent a full contingent of eligible delegates, cramming the vast convention floor to the hilt. Exchanges were hot and heavy. At one point, Munro complained that Guy was following him from microphone to microphone to respond to every criticism. “I feel like I’m pissing into the wind,” the caustic Munro raged. “Sometimes you need to do it, but you know some of it is going to blow back on you.” President George Johnston brought the house down when he responded, “Piss away, Brother Munro. Piss away.” Even Munro had to laugh.

But the rift could not be papered over with humour. Matters came to a head over the executive report endorsing a Federation independent of the NDP. After an emotional debate, the report was narrowly approved. Gerry Stoney of the IWA immediately called for a roll-call vote, a lengthy, arcane procedure in which each delegate comes to the microphone to announce his or her vote individually. The laborious process took a full day. Although the gap narrowed slightly, the Fed position still prevailed. After that, it was clear Guy would continue as secretary-treasurer, preserving the Federation as a labour organization prepared to take on all governments no matter what their political stripe.

Surprising to those in the labour movement who feared the worst, Bill Bennett’s first years as premier did not provoke a full-blown confrontation. Changes to the labour code, while significant, were not as draconian as expected. The definition of essential services was expanded, but for the moment the core of the code remained intact. Not so at the WCB. When Terry Ison was fired, to the joy of BC employers, workers lost a passionate advocate for their right to work in safety, coupled with a willingness to crack down on hazardous conditions. Just before his firing, Ison imposed a stiff financial penalty on Cominco for excessive lead levels at its Trail smelter. With him gone, the WCB returned $1 million in fines to the company in expectation they would use the money to clean up the smelter. They did, eventually, but on Cominco’s timetable rather than the WCB’s.

Ison’s hands-on approach to workers’ health and safety had also targeted the fishing industry. Harvested almost to extinction, herring had begun to return to BC coastal waters in a big way in the early 1970s. With insatiable demand for the herring’s roe in Japan, where it sold as a high-price luxury product, astronomical prices were to be had. The fishery turned into a wild, gold-rush-like pursuit of the lucrative roe. Skirting lax federal inspections, a number of boats took to the seas in risky shape. During the spring opening in 1975, two seiners and a gillnetter went down, claiming thirteen lives.

Ignoring federal jurisdiction, Ison flew to Prince Rupert and ordered WCB teams to begin checking fishboats in time for the final opening. The Fisherman newspaper hailed his bold action as “the first time in history inspectors were out in the field to protect fishermen.” Inspectors ordered several boats tied up, cited as a danger to their crews. Others were found lacking in proper equipment. The WCB continued its fishboat inspections through the 1976 spring herring fishery. But gradually, the federal Ministry of Transport (MOT) reasserted its jurisdiction. With no protest from the Social Credit government and a weaker board, fishboat inspections by the WCB ended in July. All told, their inspectors had written 4,866 orders on 585 vessels. It was back to MOT policy: no inspections of the small boat fleet and once every four years for vessels over fifteen tons.

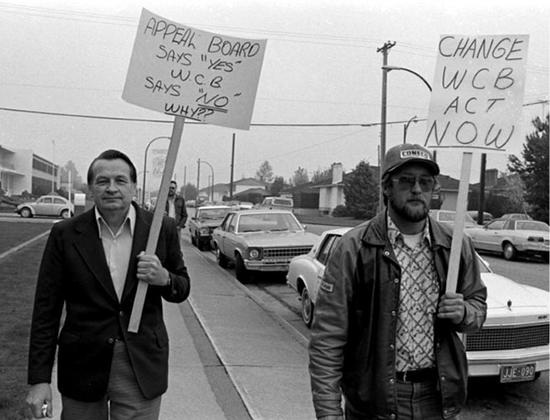

Elsewhere at the board, cost cutting resulted in serious delays processing worker appeals, while the trio of commissioners who replaced Ison declined to implement board-of-review rulings that overturned WCB decisions. In November 1976, board secretary Connie Sun was fired for resisting this policy. The brief existence of a compensation board that gave workers the benefit of the doubt was now but a memory.

Labour minister Allan Williams was an austere, white-haired lawyer who had played a key role in Bennett’s victory with his late switch from the Liberals to Social Credit. No ideologue, Williams fought off attempts within Social Credit to advance anti-union right-to-work measures similar to those in the southern United States. But he had little understanding of labour relations. Williams allowed education minister Pat McGeer, a fellow former Liberal, to push through legislation barring university faculty associations from unionization. The Labour Relations Board found McGeer guilty of an unfair labour practice for interfering with faculty bargaining rights at the decommissioned Notre Dame University in Nelson. Human resources minister Bill Vander Zalm won his anti-union spurs by not only wiping out the much-loved Vancouver Resources Board, but decertifying its fourteen hundred unionized employees ahead of the chop.

The day after Labour Day, 1977, Williams did his part by announcing changes to quell union organizing. Certification votes would now have to be won by 55 percent rather than a simple majority. That evoked such ridicule Williams soon withdrew it, with the humiliating admission he hadn’t read the drafted bill closely enough. “It was all a mistake.” There were no errors in other amendments. Employers would no longer have to provide employees’ names, addresses and phone numbers to prospective organizers, and they were now allowed to convey their views to employees during an organizing drive. After the flood of new certifications under the NDP’s organizing rules, it was back to the same old ball game. “This removes [our] shackles,” said pleased Employers’ Council president Bill Hamilton. The new measures were rammed through the legislature in such haste that Dave Barrett wondered if Williams feared “a conspiracy among working women to join a union in the next few hours and overthrow their bosses.”

It was a difficult time for labour. With wage controls in place, strikes were rare. Average annual contract increases plummeted in a single year by more than a third, from 11.9 percent to 7.4. “We’re in relatively poor shape,” confessed Len Guy. A month after the labour code amendments, workers on the expanding BC ferry fleet bucked the ebbing fightback tide, taking on the government in the biggest scrap of Bill Bennett’s first term as premier. When Williams moved to head off a union strike by imposing a ninety-day cooling-off period, the twenty-four hundred members of the newly formed BC Ferry and Marine Workers Union walked out anyway. On Friday, October 7, at a series of charged union meetings up and down the coast, ferry workers voted unanimously to keep the big boats tied up, in defiance of the government’s order. The next day, the LRB issued its own back-to-work edict. Still angered by a host of layoffs the previous year and fighting off attempts to gut their contract, ferry workers maintained their illegal shutdown through the Thanksgiving weekend.

Heading the strike was terminal attendant and rookie union president Shirley Mathieson. Just twenty-eight years old, Mathieson proved cool as the proverbial cucumber in the face of a fuming government and frothing media. An “adolescent, power-intoxicated [union is] trampling on the helpless and innocent travelling public,” encouraged by “revolutionary screaming from the BC Fed,” seethed the Vancouver Province. Looking back, Mathieson said she was neither overwhelmed nor frightened by possible legal consequences of the strike. “I didn’t know how it would play out, but it was the will of the membership,” she recalled. “It was quite exhilarating.”

On October 11, a frustrated Williams reinserted mediator Clive McKee into the conflict. A day later the union agreed to go back to work while negotiations continued. In return, LRB chairman Paul Weiler signed an undertaking that no legal action would be taken against the union or any of the strikers. Ferries resumed running on October 14. Their employees had stared down the Social Credit government, the Labour Relations Board, the BC Ferry Corporation and the Province editorial board for an entire week without blinking. Several months later, both sides accepted Clive McKee’s recommendations to settle the dispute. Takeaways demanded by the ferry corporation were gone.

Over in Victoria, Bill Bennett hated every minute the ferry workers thumbed their nose at Allan Williams’s ineffectual ninety-day cooling-off period. The moment ferry service returned, he announced a major expansion of essential services legislation—previously restricted to police, firefighter and health-care unions—to include any union whose job action the labour minister ordained was “an immediate and substantial threat to the economy and welfare” of BC and its citizens. How that exceedingly broadened definition might be applied was uncertain.

But the NDP’s measured approach to essential services strikes was clearly over. The Barrett government pioneered the designation of specific services to be maintained by striking employees. That received its trial by fire during a hospital strike by the Hospital Employees’ Union in 1976. LRB chairman Paul Weiler said that deciding which employees had to remain at work, without easing pressure on the employer or endangering patients, was “the tensest, most difficult thing I’ve ever done.” But it worked, and the HEU won the strike.

Not all labour happenings concerned the provincial government. One day in June 1977, bank worker Dodie Zerr was in the large vault of the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce’s branch on Vancouver’s Victory Square. She was about to hand over great dollops of cash to a couple of gun-toting guys from Loomis when ledger-keeper Jackie Ainsworth came dashing into the vault. “We won!” she yelled at Zerr. “It’s branch by branch!” Their downtown workplace had just made labour history. According to a Canada Labour Relations Board (CLRB) decision released moments earlier, bank workers could now be organized by individual branches. No longer would they have to wait for a union to achieve the impossible task of signing up a majority of all branch employees across the country in one mammoth national bargaining unit. With their legions of poorly paid women employees, the country’s powerful chartered banks were effectively open to unionization for the first time.

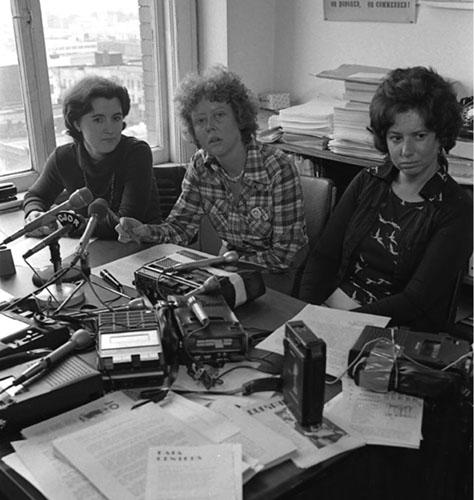

The historic breakthrough was made by the most unlikely of unions. The Service, Office and Retail Workers’ Union of Canada was everything the mainstream union movement was not. It was small, grassroots-based, staunchly political and overtly feminist, with the goal of “organizing the unorganized.” In the words of a labour relations officer, SORWUC saw itself as “an instrument of social reform rather than a bread-and-butter union.” Its specific targets were women in service occupations at the bottom of the wage ladder who tended to be bypassed by established unions as too tough to organize: restaurants, bars, fast-food outlets—and banks. Founded by several dozen women in the fall of 1972, SORWUC’s constitution stressed membership empowerment rather than top-down leadership. In its first few years, the union won a mere scattering of diverse certifications with few workers: daycares, social services units, offices, pubs and a tuxedo rental store.

With no paid staff, one typewriter, one phone, a donated mimeograph machine, a working/meeting space in a member’s basement and a band of dedicated volunteers, SORWUC decided on an audacious campaign to break into Canada’s five chartered banks. Employees deserved a greater share of the banks’ $120 billion in total assets, the union asserted. Mostly women, their starting pay hovered around $600 a month, far below the national average wage. Merit increases were arbitrary. Working conditions could be onerous, with tellers often forced to make up balance shortfalls from their own meagre earnings and unpaid overtime considered part of the job.

In fact, it was unhappiness over overtime at CIBC’s Victory Square branch that started everything. Fed up having to stay late without compensation, employees met one night at the nearby Railway Club bar. Ainsworth, an early SORWUC supporter who had entered the banking business with union thoughts dancing in her head, suggested they approach the union. The next morning SORWUC volunteers were outside the branch, handing out pamphlets extolling the virtues of unionization. Within a month, nine of the bank’s twenty employees had signed union cards. Under the federal labour code, that was enough to apply for certification.

On August 16, 1976, SORWUC submitted its application for certification to the CLRB, the first such application in seventeen years. The news lit a fire in the industry. Tiny SORWUC was soon swamped by requests from bank workers across BC. By March 1977, the union had applied to represent employees at twenty-two branches. The banks argued vociferously that single branch certifications would lead to banking chaos, but the board opted for SORWUC’s view, ably argued by lawyer Ian Donald. The union was granted five automatic certifications. Votes were ordered at seventeen other branches. It was truly a milestone decision.

The union office was “nutso,” said one member. “Phones rang all day long. We’d done what everyone said was impossible.” For the moment, the little union that could had triumphed. Although SORWUC won only three of the first seventeen certification votes, employees continued their clamour to be organized. Within a year, SORWUC had amassed twenty-four official certifications. The union’s ambitious bargaining proposals, set by employees themselves, called for an 80 percent increase in the starting wage, based on the salary needs of a single mother with one child. They also sought a thirty-five-hour week, seniority rights, double pay for overtime, involvement in shift schedules and a paid holiday on International Women’s Day.

Talks did not go well. However much they detested the pesky little union fly buzzing around them, the powerful banks were far from beaten. When SORWUC asked for centralized bargaining in order to facilitate contract talks, the banks, which had argued so strongly against branch-by-branch certifications, now insisted on negotiating by individual branch, knowing that would stretch the union’s thin resources. As often as not, this led to young female employees preparing for talks in a nearby coffee shop, then sitting across from top executives in a fancy hotel meeting room. As described by bank worker Sheree Butt, “Right on time, in walked five men, all dressed in three-piece business suits, each carrying a briefcase. They sat down and proceeded to pull mounds of paper out of their briefcases. This went on for about five minutes before the meeting could begin.” All five chartered banks used similar tactics: stall, agree to almost nothing, exhaust employee negotiators who were still working full-time and demonstrate to non-union employees there was no advantage to joining a union.

Beyond these strategies, there was also a wage freeze. While employees at non-union branches received pay raises of 5 percent, those at union branches had their wages frozen until they secured a contract. The impact was devastating. Organizing ground to a halt. Membership dwindled to a third of its former level. “Bank workers obviously felt that a wage increase in hand was worth more than [possible] improvements that unionization promised,” wrote Elizabeth J. Shilton Lennon in a study of bank organizing. Workplace intimidation also sapped momentum, as the union became mired in fighting a slew of unfair labour practices at the CLRB. The banking sector accounted for more than a third of all complaints brought to the board in 1977 and 1978, prompting board chair Marc Lapointe to admonish banks for their seemingly deliberate campaign “to discourage employees from exercising their rights under the [Labour] Code.”

SORWUC struggled forward, but the writing was on the wall. Bereft of funds, turned down by the Canadian Labour Congress in its request for assistance, stymied by the banks’ refusal to negotiate any kind of decent agreement, hampered by the smallness of individual branches, the union was running on empty. Unwilling to sign contracts containing conditions no better than those already in effect at non-union branches, and believing there was no way to win a strike against the billionaire banks, SORWUC threw in the towel. At an emotional meeting in late July 1978, members voted to take the unprecedented step of withdrawing all twenty-four of its bank certifications in BC. The banks had won. Decades later, Jackie Ainsworth remembered the acute anguish of the decision. “It was horrible. We kept going round and round,” she said. Ainsworth stayed in banking and worked her way up to become a vice-president at US Bank in Seattle. “But we knew we just couldn’t bargain a good contract. It broke our hearts.”

There were several postscripts to the union’s banking saga. After SORWUC’s breakthrough, the CLC rushed to form its own bank workers’ union. The Union of Bank Employees acquired a number of certifications across the country. Unlike SORWUC, the CLC union opted to sign status quo agreements when they could get them, providing wages and conditions similar to those of non-union employees but with an actual contract and union security in place. Over time however, despite the CLC’s clout and finances, most of their branches decertified as members questioned paying union dues for little benefit.

Yet the threat of unionization changed conditions for all bank workers. When SORWUC threatened to take the banks to small claims court over forcing employees to personally balance shortfalls, the practice ended. SORWUC also fought successfully against the banks’ use of lie detector tests. Best of all, when federal wage controls ended, bank workers received healthy pay raises. They also got a dental plan, regular coffee breaks, daily payment for overtime and improved vacations and job postings. (Once worries over unionization eased, however, banks went back to some of their old ways. In 2016, a class-action lawsuit led to a court-approved settlement awarding $20.6 million to sixteen hundred Scotiabank employees for years of unpaid overtime.)

Brief though it was, SORWUC’s success among unorganized bank workers, considered just about the toughest of union nuts to crack, was a singular chapter in the long fight of women workers to achieve respect and decent compensation from their employers. The idealism and grassroots lure of SORWUC, for all its shortcomings and ultimate failure, attracted bank workers to its fold in a way no other union managed, although unions such as the BCGEU and the United Steelworkers have made inroads in the province’s many credit unions. (SORWUC continued as a one-of-a-kind feminist union but never with anything near the impact it had had on the banks. Its last bargaining unit, representing fifty-seven home-care workers, merged with Local 1518 of the United Food and Commercial Workers in 1987.)

SORWUC’s bank endeavour was not the first advance by an overtly feminist union. Two years earlier, the brand new Association of University and College Employees (AUCE), formed by some of the same people who went on to prominence with SORWUC, won a thumping certification vote to represent twelve hundred underpaid, underappreciated and previously unorganized library and clerical workers at the University of British Columbia. The core of the union’s message was feminism: that women workers deserved to be treated and paid equally. AUCE carried that message to the bargaining table.

The result was a pioneering collective agreement that provided an across-the-board wage increase of $225 a month over eighteen months, amounting to an average pay hike of 54 percent. There were also clauses proscribing dress codes and making coffee for the boss, plus a landmark commitment to top up unemployment benefits received by women on maternity leave, so they would suffer no loss of income. This boon to working women was a BC first and soon a part of other contracts covering large numbers of women members. After this triumph, the union became a driving force on the province’s campuses, as support staff at other post-secondary institutions, including a large bargaining unit at Simon Fraser University, rallied to join.

Exploited for years, women were simply no longer willing to take it anymore. This hardening attitude, reflective of the changing times, paved the way for the ultimate goal: equal pay for work of equal value, or pay equity. That would eventually be won by larger unions such as the BCGEU, CUPE and health-care unions within the house of labour. Membership-driven unions like AUCE were absorbed over time into more established unions, offering greater security and financial support. Although AUCE disappeared, it left behind a trailblazing legacy for the victories to come.

Women were changing the labour movement. Between 1965 and 1981 the number of women in trade unions, particularly in the public sector, more than tripled. New issues emerged at the bargaining table: decently paid maternity leave, family and sick leave, and of course, pay equity.

Male trade unionists sometimes had to be educated on the changing landscape. After winning collective bargaining rights, the BCGEU launched a campaign to eliminate sexism both on the job and within its own union. Alice West, the wartime plywood plant worker, worked her way up to national director for BC in the Public Service Alliance of Canada (PSAC) representing federal civil servants, only to find she was not taken seriously by male union leaders. “It took a while to get ‘the suits,’ as I call them, to listen to us,” West recalled. “When women began speaking up, they weren’t used to it.” She and other PSAC women negotiators took on the issue of paid maternity leave. When they finally achieved it they were thrilled, only to be subjected to a backlash from many PSAC men and some older women who resented a benefit they couldn’t use. The historic breakthrough turned bittersweet, said West. “We hadn’t done a good enough job explaining the issue to our members.”

In 1973, women shore workers in the fishing industry finally won parity with male plant workers after years of wage discrimination, boosting their rates by 35 to 75 percent. About the same time, the Hospital Employees’ Union launched its long, ultimately successful campaign for pay equity in the province’s hospitals. There was no going back.