17. New Tactics and Workplace Tragedies

Much to Bill Bennett’s surprise, Social Credit almost lost the 1979 election. A rewarming of voters toward Barrett and the NDP and a lacklustre campaign left the Socreds with only a narrow, five-seat majority. Bennett cleaned house, turfing party veterans in favour of young, smart, talented political operatives, many from Premier Bill Davis’s “Big Blue Machine” in Ontario. They brought with them a neo-conservative gospel of reduced government and a free market unrestricted by such inconveniences as unions. The years that followed would be defined by almost constant warfare between a strong-willed Bennett and an equally resolute trade union movement, culminating in the most heartfelt and concerted protest movement in the province’s history.

Decades later, the uprising known as Operation Solidarity remains as a distinctly astounding event that brought hundreds of thousands of British Columbians into the streets in a never-to-be-forgotten crusade for social justice and basic union rights. On the other side, the war was fought under the all-encompassing umbrella of “restraint,” Bennett’s term for everything his government did to combat the province’s worst economic downturn since the Great Depression. But much of what was unleashed had more to do with ideological conviction than any prescription for the economy.

Fittingly, the 1980s kicked off with an inspiring struggle against an employer whose aggressive anti-union approach unsettled even the Employers’ Council. The US-owned BC Telephone Company had put the Telecommunications Workers Union (TWU) through a difficult three-month lockout in 1977–78. The union entered the next round of talks in 1980 determined to pressure the company without triggering another lockout. The head-butting began after BC Tel rejected proposals by conciliation commissioner Ed Peck as too generous and too restrictive for its workplace authority. A one-time company negotiator himself with the towboat industry, Peck noted that BC Tel had “an exaggerated notion of management rights.” When TWU members voted 81 percent to accept Peck’s proposals, the die was cast.

The union launched its action plan on September 22, 1980. Five hundred and thirty craft employees—who repaired business switchboards, did wiring work on new buildings and installed new telephone systems—refused all work but emergency repairs. The TWU aimed to cut off these money-making areas while keeping most members on the job. Idled craft workers spent their time playing parking-lot volleyball, endless games of Monopoly, cards, chess and checkers. Those remaining at work contributed $13 a week to provide them with 70 percent of their regular salaries.

As unfilled orders piled up, BC Tel began dispatching supervisors to do the work. Mobile pickets tailed the supervisors wherever they went. Management drivers ran amber lights, dashed the wrong way up one-way streets, dodged in and out of traffic, but were rarely able to shake the tenacious picket squads. As in the past, members of the building trades walked out whenever TWU picketers showed up at a construction site.

In December the company began to squeeze the union. A thousand employees were temporarily sent home for wearing buttons proclaiming the union’s desire for a “Crown Corporation Now.” Cars bearing the same message on bumper stickers were banned from company parking lots. Early in 1981, BC Tel started suspending workers for “low productivity.” At the end of January, more than a thousand employees were on permanent suspension. TWU strategists knew something bold was needed to head off another lockout. What if, someone suggested, workers simply refused to leave in the event of a lockout and took over operation of the phone company?

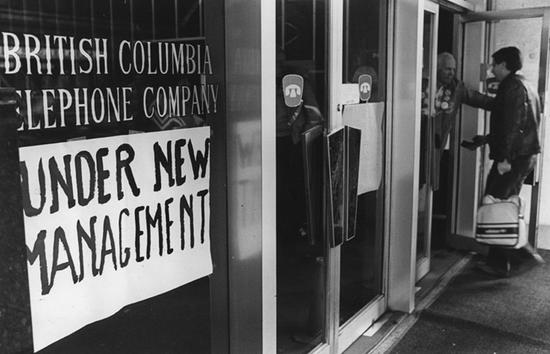

The spark was lit on Vancouver Island. On February 3, twenty-one maintenance workers in Nanaimo were suspended for “going slow.” Employees gathered in the main lunchroom and, just like that, they began to occupy the building. Workers took control of the switching equipment and switchboards. Shop stewards drew up round-the-clock shift schedules. During the evening, replacements arrived with sleeping bags and provisions. A banner hanging from the company’s microwave tower declared, UNDER NEW MANAGEMENT. “We’re just your common switchmen,” suspended employee Alf McGuire told reporters. “When ordinary people get desperate enough to take over a building, things are getting pretty desperate.” With no supervisors, the mood was jubilant.

On the morning of February 5 in the supply depot at BC Tel’s high-rise “boot” in Burnaby, shop steward Lila Wing was told to leave and change her anti-company T-shirt before returning to work. When Wing asked the union for direction, the TWU called on workers to take over the building. Similar instructions were issued to employees at fourteen additional company exchanges throughout the province. By the time the clock struck twelve, the deed was done. TWU president Bill Clark told the public that union members would be staying at their posts, providing basic telephone service twenty-four hours a day.

Switchboard operators were soon answering information calls with “TWU directory assistance” or “BC Tel, under workers’ control.” There was a new feeling of co-operation and solidarity among union members, who mingled in areas they had never visited before, learning and appreciating what their co-workers did. The media, police and company managers were invited to tour the occupied facilities to observe the lack of damage to equipment. With its incessant rate increases, seen by many as gouging, and its rejection of the Peck report, BC Tel had few admirers. The union’s unlikely seizure of BC Tel premises captured the imagination of the public. While BC Tel railed about “anarchy,” papers like the Daily Times in Nanaimo saluted union members for “pulling off a diplomatic coup.”

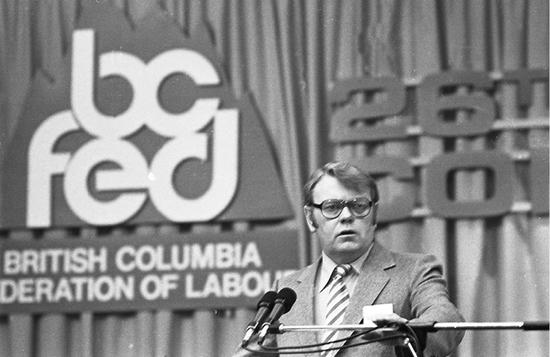

The situation energized the BC Federation of Labour and its steely president Jim Kinnaird. A former head of the BC building trades who also spent time as deputy labour minister under the NDP, the forty-eight-year-old Kinnaird had taken over the Fed from Len Guy in 1978 and managed to soothe its divisions. Normally soft-spoken and low-key, he could be hard as nails when riled. Noting other ongoing labour disputes in the province, Kinnaird accused BC employers of thwarting labour’s legitimate aspirations with injunctions, drawn-out wrangles at the LRB and inflexibility at the bargaining table. In a fiery speech at a public rally in support of the telephone workers, Kinnaird declared “industrial relations war” on the employers of British Columbia. Evoking Tom Joad’s spellbinding farewell vow of commitment to his mother in The Grapes of Wrath, Kinnaird told the crowd that wherever workers were on the line, the BC Federation of Labour would be there, and wherever workers were punished for taking a stand, the BC Federation of Labour would be there. “Tonight I am telling you, we are going back, back to the old, bare-knuckled ways of fighting labour disputes,” declared Kinnaird in his distinctive Scottish accent. “The gloves are off.” He announced a series of regional general strikes to begin within a week.

Police made no move to end the occupation. They waited for the courts to deliver their verdict. That came on day five. The BC Supreme Court found the TWU guilty of criminal contempt of court for ignoring an injunction against occupying BC Tel property, fining the union an indeterminate amount to be increased each day the occupation continued. The prospect of losing all its assets left the union with little choice. The executive ordered its members onto the streets to begin a full-scale strike.

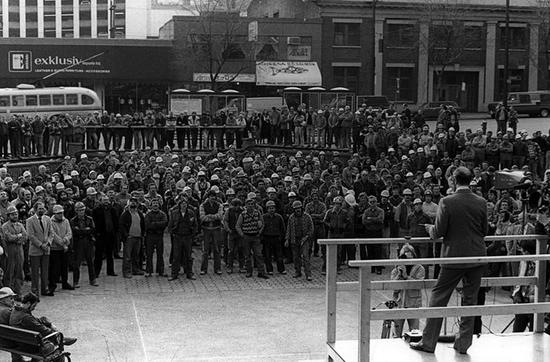

The last building to empty was the company’s twelve-storey “nerve centre” in downtown Vancouver. At noon the next day, hundreds of workers poured from the building in a lengthy, spirited procession led by a union bagpiper. They were joined by hordes of noon-hour construction workers and other supporters who filled the street and crowded all four levels of a parking garage overlooking the building. Speeches of support were delivered by Jim Kinnaird and Jack Munro, who ended the rally with the worst rendition of “Solidarity Forever” ever heard at a union gathering. “I’ve got to admit, I’m the worst singer in the goddamn crowd,” laughed Munro. More seriously, Bill Clark told TWU members to report to their picket captains. “Let’s get to it.”

Although the first workers’ occupation of its kind in BC was over, morale among the strikers was through the roof. The federal government and even other employers began to fret about BC Tel’s attitude. Observing that the company was “perhaps not as sensitive to the situation in British Columbia as might be desired,” federal labour minister Gerald Regan sent in troubleshooter Bill Kelly. Over the years, the veteran red-haired mediator had helped resolve some of the country’s most difficult labour disputes. He had seen just about everything. Nothing prepared him for BC Tel. In a move that the Province newspaper said could come “only from someone dwelling in Never-Never-Land,” the company insisted it could not improve its wage offer without yet another rate increase from the CRTC. “That’s a new experience in any mediation I’ve been involved in,” Kelly said. He returned to Ottawa.

Private pressure from a worried employer community and a wave of negative public opinion finally forced BC Tel back to negotiations. On March 2, 1981, the parties reached a tentative deal, embracing Ed Peck’s wage package of long ago, plus more accumulated time off and a compromise on jurisdiction and scheduling. But that did not end the strike. BC Tel refused to take back twenty-four workers fired during the strike. The union would not return without them. The one-day regional strikes vowed by Jim Kinnaird were back on. Nanaimo, scene of the first TWU occupation, was chosen for walkout number one.

On March 6, a makeshift sign posted at the entrance to the Vancouver Island city announced in large letters, NANAIMO CLOSED. It was. Thousands of private- and public-sector union members took the day off. PPWC members at the large Harmac pulp mill put aside their differences with Fed affiliates to walk out too. “We are with the Telecommunications Union 100 percent,” said Harmac local president Bill Bryant. From dawn to midnight, almost every union work site in the area was shut tight as a drum: ferries, supermarkets, liquor stores, government offices, the post office, construction sites, buses, sawmills, the docks. It was a prime example of union solidarity. The next strike, Kinnaird said, would take place in the Kootenays, halting production at the giant Cominco smelter, a number of mines and a wealth of sawmills.

BC employers became increasingly nervous that this union muscle-flexing would spill over into their own negotiations. In private, they increased heat on the telephone company to settle the dispute once and for all. The upshot was an agreement to submit the twenty-four firings to Prince George arbitrator Allan Hope for a quick decision before a return to work on March 23. Fifteen months after their old contract had expired, after a rousing six-week strike, the TWU’s ten thousand members voted to ratify their new agreement.

They returned to work in triumph, having wrestled the most obstinate employer in the province to the ground. There was one further bonus. Arbitrator Hope rescinded the firings of all twenty-four employees. Stunned, the company appealed to the BC Supreme Court, which overturned Hope’s decision. But by then BC Tel no longer had the will to evoke more bitterness. The fired employees stayed at work.

There was no such victory in the field of health and safety. The tough sledding of the latter 1970s continued into the 1980s. The labour movement was in perpetual conflict with a Workers’ Compensation Board that was underfunded, poorly run and tilted toward employers. Workers continued to be maimed, injured and killed on the job in distressing numbers, guilty of nothing more than going to work. There was little publicity for most of those who perished, their deaths noted only by grieving families and mourning workmates.

But what happened January 7, 1981, in downtown Vancouver was different. It would continue to resonate for decades after three journeymen carpenters and one apprentice ventured that sunny afternoon onto the outer edge of a construction work platform known as a fly form on the thirty-sixth and final floor of Bentall Tower IV. The building was close to completion as the highest of a multi-tower development on Burrard Street. Without warning, the fly form toppled over the edge, hurling the four men to gruesome deaths on the concrete plaza far below. “I heard a noise. I turned around and the panel was gone,” said co-worker Dieter Goeldner.

Killed were Brian Stevenson, twenty-one; Donald Davis, thirty-four; Yrjo Mitrunen, forty-six; and Gunther Couvreux, forty-nine. Their deaths shook everyone in the construction industry and beyond. In an emotional statement at the coroner’s inquest, read for her after she broke down in sobs, widow Carol Davis said that her husband had walked out onto the platform “convinced in his own mind, absolutely, that he was safe.”

The inquest was thorough. After eight days of intense testimony from workers, contractor representatives, independent experts and relatives of the dead men, the culprit was clear. The fatal fly form used in the floor-by-floor pouring of concrete had been “grossly under-designed” by its supplier, Anthes Equipment Supply of Toronto. Dominion Construction was also faulted for paying insufficient attention to the fly-form drawings and its assemblage. And the WCB was singled out for irregular inspection of the site and a failure to enforce existing industrial health and safety regulations.

Jury members worked past midnight to craft a series of recommendations to ensure such a tragedy would not happen again. They were undoubtedly affected by words at the inquest earlier that day from Kit White, mother of Gunther Couvreux. “What a terrible way for five women to become friends,” said White, referring to the sad bond formed by survivors of the victims. “Four men are dead. Four children ages six to thirteen are fatherless. Who cares? Who will look after them? … Life seems cheap in the construction industry. How many more will die before changes are made?” Her five-minute statement left many of those present sniffling and blinking back tears. An official termed it one of the most moving scenes he had witnessed in twenty years of attending inquests.

In addition to tightening the design, construction and professional scrutiny of construction fly forms, the jury demanded more on-site inspections by the Workers’ Compensation Board, clearer written regulations, increased on-the-job safety education and diligent compliance with safety standards. Finally, the jury—two carpenters, two engineers and a construction labourer—called on labour minister Jack Heinrich to strike a comprehensive inquiry into all aspects of safety in the BC construction industry.

A month later Heinrich appointed the Construction Industry Safety Inquiry, the first in-depth look at construction safety practices in years. With a panel of union, company and engineering representatives, the inquiry spent a year touring the province, holding public meetings, visiting construction sites and determining what needed to be done. By December, a special group had prepared a meticulous list of regulatory changes to address the urgent matter of fly-form safety. The most advanced in North America, they were quickly put in place. There has not been a fly-form fatality since.

The final report contained sixty recommendations to address carnage in the construction industry. The panel found a direct link between fewer WCB inspections and a higher accident rate. After initial resistance, the WCB accepted the need to hire more construction inspectors and visit all sites at least once a month. Another offshoot of the report was the Construction Safety Advisory Council, a permanent, multipartite body to oversee workplace safety in the industry. Small consolation as it may have been to their surviving families, the four workers did not die in vain. Improved practices live on after them. Each year on the anniversary of their deaths, a memorial gathering takes place at a small pocket park in the shadow of Bentall Tower IV to remember them and renew the commitment to safety on the job.

Not that far from the Bentall Tower and other gleaming office towers, away from the view of most Lower Mainlanders, conditions akin to the Third World prevailed on many farms in the Fraser Valley. Thousands of mostly South Asian immigrants toiled long hours in the summer heat, under the heel of labour contractors who skimmed their low wages and farm owners who relegated them to abysmal living quarters. Young immigrant Raj Chouhan was shocked by what he found when he sought work on a few farms. “There was no running water, no toilets, absolutely no facilities,” Chouhan told a Burnaby Now reporter years later. Employees often lived in converted barns, six to a cubicle, their kids among them. “I was expecting, in a country like Canada, there would be something better than that,” said Chouhan. When he asked questions, he was fired, and the young immigrant had a cause.

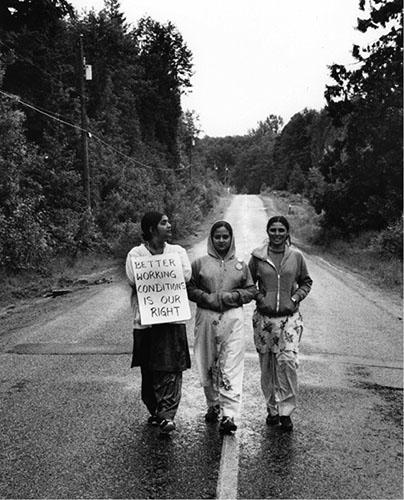

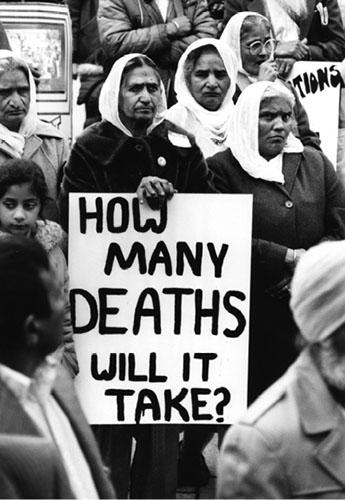

Stretching into the 1980s, along with Sarwan Boal, Judy Cavanaugh, Charan Gill and the IWA’s Harinder Mahil, aided by scores of volunteers and supporters, Chouhan led a valiant effort to organize Fraser Valley farm workers, publicize their plight and secure decent working conditions. Against the farm workers were an indifferent Social Credit government that purposely excluded them from regulations and labour standards covering other BC workers, a recalcitrant WCB, intimidation and violence. Yet they persevered, winning certifications and shining a spotlight on the dark corner where farm workers had been shunted by government and an unaware public.

Most farm workers spoke no English. Two-thirds were women. New to Canada, they were fearful of their fate if they complained. But privately, many detailed their grim situation to Chouhan and others in the community. On February 28, 1979, a small group gathered in a room at the New Westminster library to form the Farm Workers Organizing Committee (FWOC). It did not take long to have an impact. That summer, Mukhtiar Growers was beset by picket lines and walkouts until the owner forked over $80,000 he owed in back wages. On another occasion, a three-mile organizing march by more than a hundred FWOC supporters along farm-lined Huntington Road in Abbotsford drew farm workers out of the fields to join them. “Our purpose is to show the farmers and contractors that we will not be intimidated,” Chouhan declared at a wind-up rally in front of their ramshackle living quarters.

On April 6, 1980, to the rousing cry of “Zindabad!” (long live!), the FWOC upgraded itself into a union. Despite strong pledges of financial support from BC unions and the Canadian Labour Congress, organizing proved daunting. Ten days after formation of the Canadian Farmworkers’ Union (CFU), bat-wielding thugs attacked the home of vice-president Jawala Singh Grewal, smashing windows and trashing his pickup truck. On his way home from a banquet celebrating the union’s first certification at Jensen Mushroom Farm in July, Sarwan Boal was savagely beaten. It would take two years and a long, difficult strike before the CFU was able to win a first contract at Jensen’s Langley farm.

In the meantime, tragedy swept the growing fields. Sukhdeep Madhar, a seven-month-old baby, drowned when she rolled off a small bunkbed into a large bucket of drinking water in the converted horse stall used to accommodate her family. The farm owner, whose mansion, Cadillac, Mercedes-Benz and tennis courts were close by, had provided no running water. Barely a week later, three young boys, left to play by themselves while their parents picked berries, drowned in a nearby abandoned gravel pit. The deaths shocked British Columbians. Decrying the “horror” of living conditions on the farm, a coroner’s inquest into the infant death called for immediate inspections of all agricultural accommodation in the province. For the families of the three drowned boys, the CFU helped win $30,000 in damages from the gravel-pit owner.

The union pressed forward with demonstrations, public meetings and well-researched briefs, backed by a supportive media and public. Under pressure, the government announced WCB coverage would be extended to agricultural workers effective April 4, 1983, only to renege on its commitment just before that spring’s election campaign. Raj Chouhan lambasted the turnabout as Social Credit’s “most dishonest betrayal.”

Then there was another death. With no comprehensive regulations or mandatory training in place, nineteen-year-old farm worker Jarnail Singh Deol died of pesticide poisoning. “Jarnail’s death stands as a monument to government inaction,” raged the usually even-tempered Chouhan. “To those who demand patience, to those who are tired of our voices shouting for equality, we say, ‘No more deaths! No more watching our young people die!’” Finding Deol’s death “a preventable homicide,” an inquest jury recommended effective pesticide regulations and strict enforcement to prevent similar fatalities in the fields. The WCB began the process, but once again failed to follow through. Farm workers would have to wait until 1993 before they were brought under the same health and safety umbrella as other BC workers.

On the organizing front, inspired by the example of California’s brave organizer Cesar Chavez, who came up several times to lend his voice to the struggle, the CFU fought hard to bring farm workers the protection of a union contract. Bell Farms in Richmond was one of the few growers to accept the union. Covering ten full-time and thirty seasonal employees, the CFU contract at Bell Farms prescribed a forty-hour week, benefits and improved wages. A union hiring hall replaced the use of labour contractors.

Most growers fought the union every step of the way, mounting costly legal challenges, discriminating against union supporters, and intimidating workers with threats and firings. A gruelling strike at Jensen Mushrooms ended with good raises, benefits and April 6 as a holiday for Farmworkers’ Day. But the farm rehired few of the original workers. Four months later, the union lost a close vote to decertify. A long strike against Country Farms Natural Foods, which included picketing of the owner’s popular Naam vegetarian restaurant in Vancouver, was never resolved.

Organizing drives at Choi Mushrooms and Hoss Farm typified the uphill battle. In both cases, workers who joined the union were fired. To get their reinstatement and back wages, the union had to fight long and hard at the labour board and in the courts. It took nearly four years and a Supreme Court order to force Choi’s single-minded owner to pay out the $35,000 he owed his illegally fired workers.

At Hoss Farm, the fired women began picketing the next day. “I feel good about the picket line, because we are fighting,” said Jasweer Kaur Brar. But it took an all-out campaign by church groups, social organizations and the labour movement, including a “hot” declaration against Money’s Mushrooms, which used Hoss as a supplier, before the owner agreed to take back seven of the eleven fired women. Although certified at each location, the union was unable to reach a collective agreement at either farm.

The exhausting slog needed for the most minimal advances eventually wore down the union’s leaders, dogged by burnout and years of meagre incomes. They left to take other jobs, and the Canadian Farmworkers’ Union began to fade. Yet there was a strong sense its success could not be measured solely in certifications. The CFU was as much a social movement as a traditional trade union. With the help of the BCTF and Frontier College, the union had launched a successful “ESL Crusade” to teach Punjabi-speaking farm workers basic English. Instructional videos were produced on the safe use of pesticides and other health and safety practices. The union’s high-profile campaign on behalf of immigrants at the bottom of the wage scale and victims of abominable working conditions represented a social activism that began to hammer cracks in the Social Credit dynasty through the rest of the 1980s.