13. A New Nationalism

The 1960s ushered in a new sense of nationalism and confidence, capped by the outstanding success of Expo 67 to celebrate Canada’s centennial. The inferiority complex of the postwar years, when the country fell under the large shadow of the United States, was shunted aside. Aided by a new flag, Canadians found that they too could be a proud country, able to stake their own place in the world. These feelings also played out in the country’s labour movement. Some Canadian trade unionists belonging to international unions, which made up the bulk of organizations within the Canadian Labour Congress, were becoming dissatisfied with top-down rule from their unions’ American leaders. Some began looking for alternatives, as Tom McGrath had with his Canadian Ironworkers Union. They wanted autonomy to make their own decisions, without being second-guessed or overruled by union officials in the United States.

No union in BC was more challenged by this emerging sentiment than the International Brotherhood of Pulp, Sulphite and Paper Mill Workers, which represented almost all of the province’s pulp and paper workers. Angus Macphee, a self-proclaimed socialist mill worker from Prince Rupert, and Orville Braaten, a bright, committed, left-wing trade unionist from Vancouver, were part of a cross-border group pushing for reform within the International. They were protected from the anti-communist purges that swept other US unions by Pulp Sulphite’s venerable president John “Paddy” Burke, who had led the union since 1916.

Just before the union’s 1962 international convention in Detroit, however, with the seventy-eight-year-old Burke about to retire, US immigration officials barred Macphee and Braaten from entering the country, citing their recent visits to Cuba. BC delegates who did make it to Detroit often had their microphones turned off when they attempted to speak. Not even a motion to allow Canadian locals to affiliate with the NDP passed muster. Al Smith from the Woodfibre local remembered, “As I left the convention hall, I felt dirty, depressed and a bit dazed. I crossed back into Canada and took a bath.”

For Macphee, Braaten and several others, the Detroit convention was the last straw. Feeling there was now no chance of reforming their international union, they decided to establish an independent Canadian union for pulp and paper workers. Although radical at the time, the idea quickly found favour. The founding convention of the fledgling Pulp and Paperworkers of Canada (PPWC) took place just four months later, in early January of 1963. Five of the province’s eleven pulp mills were represented. And the breakaways began.

Crofton was the first mill to go. Under the local leadership of Bill Cox, workers voted 94.6 percent to join the PPWC, once the union’s name on the ballot had been corrected from the “Pulp and Paperworkers of America.” The International fought back, imposing new leadership, sending in vice-president Henri Lorrain from Montreal to try to reason with the members and putting the local under trusteeship. But Cox had planned well, securing the local’s assets and making sure all legal requirements were followed. More than 85 percent of the three hundred Crofton mill workers subsequently signed PPWC cards, and on June 26, the new local was officially certified.

Yet Crofton was not the first PPWC local. That distinction belonged to workers at the Castlegar pulp mill. The previous year, before any talk of the PPWC, they had bolted from another international pulp union, the smaller United Paper Makers and Paper Workers Union. They were the first group of Canadian pulp and paper workers to negotiate their own agreement, independent of a parent organization. A few weeks before the Crofton mill formally joined, Castlegar mill workers decided to cast their lot with the PPWC as Local 1 of the new union. Angus Macphee’s mill in Prince Rupert and Woodfibre soon followed. By the end of the year, with the addition of certifications in a new Vancouver local, the PPWC had five locals and two thousand members.

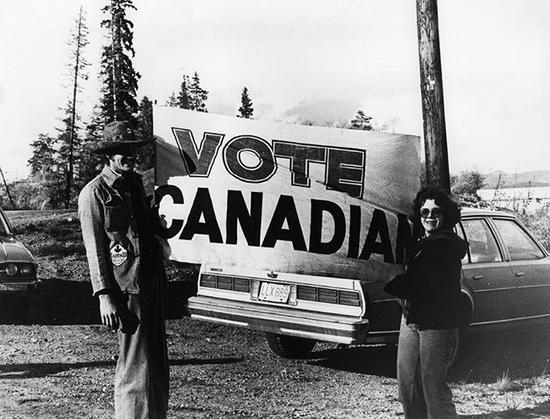

At the beginning, with strong local leadership, workers needed little convincing to opt for the PPWC, which soon changed its name to the Pulp, Paper and Woodworkers of Canada. They responded to the union’s prominent nationalism, leading critics to mock the PPWC as “flag-wavers.” Each local was autonomous, officers were elected annually by referendum, conventions were held every year, and none of its few full-time business agents and leaders could earn more than the highest rate in the mill. As well, unique among unions in Canada, after five years working for the union, officers had to rejoin the workforce for at least one year.

Stan Shewaga, perhaps the most well-known PPWC leader over the years, said he didn’t mind going back into the mill to resume his trade as a millwright. “It’s good for you, and it’s good for the membership,” he reflected. “When you go back to work, it makes the guys feel good. ‘He’s one of us.’” Shewaga added with a chuckle, “And you end up making more money than you did as a porkchopper.” (“Porkchopper” is a colloquialism for a full-time employee of a union, sometimes used derisively, sometimes humorously.)

Dissatisfaction with Pulp Sulphite was not confined to British Columbia. After one more failed convention attempt to push through reforms, twenty-eight thousand union members in Washington and Oregon also left in favour of a new independent union. But the battle for worker allegiance continued to grow in British Columbia, fought out at a number of other pulp mills. The PPWC also made forays at some IWA sawmills and a bold but unsuccessful effort to represent workers at the large Alcan smelter in Kitimat who had become increasingly unhappy with their union, the United Steelworkers of America.

Raiding is loathed by many in the trade union movement. They believe it deflects focus and resources away from fighting the boss. Some also consider it immoral to pick off already unionized bargaining units rather than organizing the unorganized. The CLC has strong rules against inter-union raiding. (The BC Nurses’ Union has been suspended from the CLC since 2009 for raiding other health-care workers.) On the other hand, the right of workers to change unions is guaranteed under the Labour Code, providing a vehicle for them to leave a union they feel no longer adequately represents them. But there is no softening the animosity a raid evokes. Like a civil war, it strikes at the heart of solidarity, pitting union brothers and sisters against one another.

Raids were plentiful in BC in the 1960s and 1970s, most of them clashes between American-based unions and independent Canadian unions seeking to supplant them. Although the independent unions—grouped together after 1969 into the Confederation of Canadian Unions—did by no means sweep the BC labour movement, unions such as the PPWC, the Canadian Association of Industrial, Mechanical and Allied Workers (CAIMAW), the Canadian Association of Smelter and Allied Workers (CASAW) and the Independent Canadian Transit Union (ICTU) made notable inroads into the province’s labour movement.

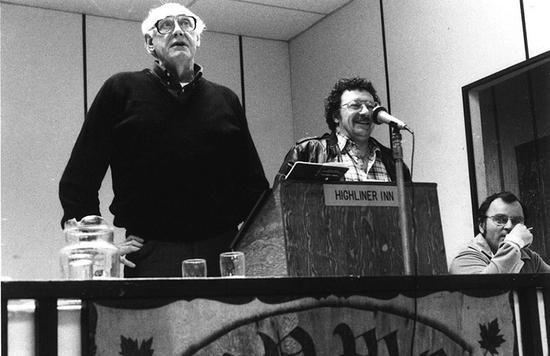

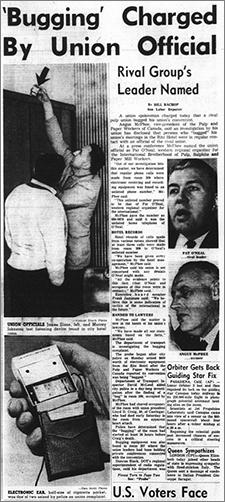

The PPWC’s early successes led to the infamous “bugging caper,” one of the most bizarre events in BC labour history. It was engineered by one of labour’s most colourful and controversial figures, the unique Pat O’Neal. Unquestionably talented, O’Neal had been lured from his post as secretary-treasurer of the BC Federation of Labour to return to his old union, Pulp Sulphite, specifically to stop the bleeding of members to the PPWC. His murky background, which emerged only after he ended his eight years in the Fed’s top job, became a legend in labour circles. Not Pat O’Neal at all, he was really Tommy Joe Casey, a native of Ireland’s Mayo County. In 1947, he abandoned his British merchant vessel, the Samadang, on its arrival in Victoria. The brash ship jumper took the name of an American uncle, Edward Patrick O’Neal.

O’Neal wound up in Prince Rupert, where he worked in a fish cannery before getting a job at the pulp mill. By 1952, he was president of the Pulp Sulphite local. Two years later, the Irishman was on the BC Federation of Labour’s executive council. In 1956, he ran successfully against the reunited Fed’s official slate to become a vice-president, and in 1958, he completed his remarkable rise with election to the organization’s full-time position of secretary-treasurer. During his time there, O’Neal boosted the Fed’s public profile and forged a credible fightback capacity for an organization that, when he took over, had only recently shed its divisive past.

But he chucked his job at the Federation to anchor Pulp Sulphite’s increasingly desperate struggle to retain its BC membership. At the time, Harmac in Nanaimo, Elk Falls in Campbell River, and Prince George had strong PPWC certification applications pending at the Labour Relations Board. Nor was the cause helped when Pulp Sulphite’s international vice-president Joseph Tonelli showed up at a packed union meeting of Harmac workers and began by referring to them as “You boys from Heymac here …”

But the LRB handed O’Neal and the International a huge reprieve by rejecting all three PPWC applications on the grounds that the Canadian organization was not a bona fide union under provincial labour legislation—notwithstanding its existing five certifications and collective agreements. There were strong protests in all three communities, but O’Neal drew heart from the ruling, embarking on a province-wide tour of pulp mill locals to boost the International’s standing with the help of paid-for radio show appearances.

What followed could have come from Ripley’s Believe It or Not! In early November 1966, PPWC executives gathered at Vancouver’s Ritz Hotel to prepare for their fourth annual convention. When Angus Macphee awoke the morning of November 5, he found his roommate, national president Lloyd Craig of Castlegar, dead on the floor, victim of a heart attack. Still in shock, PPWC officials decided to rearrange the room for another use. As they moved some furniture, a small object fell from the top of a wardrobe. No one knew what it was. Not long after that, a hotel switchboard operator who was friendly with one of the PPWC delegates passed along some startling information. She had noticed a large number of calls from Room 309 directly above the PPWC rooms to an unlisted number in Vancouver, which was traced to the residence of Pat O’Neal. When she listened in on one of the calls, she heard someone giving a precise account of what PPWC representatives were saying.

The light bulb went off. They were being bugged. In full film noir mode, the union called in Ace Investigations. The detective agency found three more listening devices. When police burst into Room 309, they found a chagrined private detective named Bud Graham and $700 worth of electronic equipment. The plot thickened when Graham confessed on air to radio hotliner Jack Webster that O’Neal had given him $250 for his services. After first denying any knowledge of the bugging, O’Neal ’fessed up, insisting the action was not illegal, which indeed it was not. But news of the bugging caused a public uproar, prompting Premier Bennett to appoint a Royal Commission into the matter.

Commissioner R.A. Sargeant, seemingly charmed by O’Neal’s blarney on the witness stand, exonerated the bugger and punished the buggee. Who should wind up in jail but the PPWC’s Orville Braaten, sent there by Commissioner Sargeant for contempt of court after refusing to answer questions about his political past. A BC Supreme Court justice quashed the decision.

Many trade unionists, particularly in the IWA, were outraged by the bugging. Weldon Jubenville, head of the IWA’s Duncan local, said labour should dissociate itself from anyone who would “hire private eyes to spy on his fellow workers.” Vancouver IWA president Syd Thompson called O’Neal’s actions “harmful and detrimental to the entire labour movement and [especially] international unions.” He demanded O’Neal’s removal from the Fed’s executive council.

O’Neal agreed to resign, but far from chastened, he and the International resumed playing hardball against their rivals. They demanded Harmac fire nearly eight hundred of its pulp mill workers for paying dues to the PPWC instead of Pulp Sulphite, which was still the union of record. The LRB averted a showdown by certifying the PPWC at the Nanaimo mill without a vote, citing the union’s overwhelming membership support.

But at Prince George Pulp and Paper, at the behest of O’Neal, the company fired five leading PPWC activists for refusing to pay dues to Pulp Sulphite. The group maintained a lonely picket protest through the frigid Prince George winter before the LRB ordered a vote at the mill. The PPWC prevailed 344 to 129, and the fired employees were quickly rehired. Before the decade was done, the independent Canadian union picked off three more mills. Still, O’Neal managed to head off other potential breakaways and keep a majority of the province’s expanding pulp mills within the international union.

Few would deny the impact of the PPWC’s grassroots trade unionism. Rocked by defections in BC and the western United States, Pulp Sulphite merged with the United Paper Makers to form the United Paperworkers International Union (UPIU). In 1974, Canadian members peacefully left the UPIU to establish their own Canadian Paperworkers Union (CPU), an entirely Canadian union with no ties to its former international unions. This historic decision was the first of a number of other voluntary separations that took place between Canadian and American sections of international unions in the years ahead, as workers felt increasingly comfortable belonging to a Canadian union free of international ties.

Much to the surprise of those who had booted it out of the CLC, the left-wing Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers’ Union survived into the 1960s as the province’s chief mining union. Members stuck with the lone-wolf union during the worst of the “Red scare,” appreciative of its leaders and the job they did representing them. As battles accelerated, Mine Mill hired several committed young organizers including Vince Ready, a non-communist who went on to become the most accomplished mediator in Canada. Ready barely missed death in 1965 when a thunderous avalanche swept over the camp at the new Granduc copper mine near Alaska. Twenty-eight miners lost their lives, and the main bunkhouse was split in two. Ready, who had taken a job to help keep the mine in Mine Mill hands, happened to be sleeping in the far end of the bunkhouse. The rest of the building was demolished.

The union continued to wage strikes, most notably at the Britannia copper mine on Howe Sound north of Vancouver. The multi-month dispute, lasting into 1965, inspired a song by a mine employee that was resurrected fifty years later by folk singer Sarah Jane Scouten. Referring to the company’s threat to close the mine, one verse went: “My son, I worked the miner’s trade with dignity and pride,/ Until they forced us out on strike, with Mine Mill on our side/ They tried to break our union, a lesson to us teach,/ And that’s the cruel reason they closed down Britannia Beach.”

Yet raids on Mine Mill locals did not let up. Although the union retained almost all its BC certifications, the constant warfare was wearying. Back east, the union had finally lost its huge Inco local in Sudbury to the relentless United Steelworkers of America by fifteen votes. Mine Mill leaders made the difficult decision to seek a merger with their bitter foes, the Steelworkers. “Mine Mill was broke,” said Trail local president Al King. “There was fear we’d end up without any union.” The merger, effective on Canada’s one hundredth birthday, July 1, 1967, guaranteed jobs for Mine Mill leaders, among them Harvey Murphy, who had poured his heart and soul into the union for more than twenty-five years. Members voted strongly in favour, including those at Trail, who had resisted so many forays by the international union. But there was no denying the emotional residue from one of labour’s most long-lasting inter-union conflicts. “I swallowed my pride and voted for the goddamned thing, because in my mind, there was no alternative,” said King. The most radical, tenacious mining union the province had ever seen, from its beginning as the Western Federation of Miners, faded into the sunset, still beloved by its loyal, diehard supporters.

While most BC members were content with their US-based unions, international interference in some locals continued to cause problems. One of the most contentious examples took place at Lenkurt Electric, a telecommunications equipment manufacturing plant in Burnaby. The Lenkurt workers were represented by Local 213 of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW), with a long, progressive history in BC. Granted IBEW’s first charter in Western Canada in 1901, the local followed up its organization of early telephone linemen by signing up women telephone operators at the Vancouver phone company, which eventually became BC Tel and later Telus.

Organized into an auxiliary local, the women held their own meetings and elected their own officers. Both 213 units took part in the month-long general strike in Vancouver to back the Winnipeg General Strike. This led to its first run-in with the IBEW’s international leadership. Disliking the strike’s ties with the radical, all-Canadian One Big Union, the International suspended Local 213’s charter until it was restored a year later by a court order. Differences endured over the years as Local 213 continued to wage aggressive strikes and the International expelled elected business agent George Gee for his communist sympathies in 1955.

This cauldron of dissent and tension boiled over at Lenkurt Electric in 1966, Already upset by the International’s firing of assistant business agent John Morrison, Lenkurt’s mostly women employees elected a tougher new shop steward committee headed by George Brown. During difficult contract negotiations, members voted to impose a ban on overtime at the plant. Local management agreed to the ban, but Lenkurt higher-ups nixed it. Angered by the company’s turnabout, a majority of employees walked off the job April 27 on a wildcat strike. The company responded by firing all 257 strikers, and the battle was on.

The dispute turned into a cause célèbre. Much of the labour movement joined with the fired employees in defying a quickly obtained court injunction against picketing. Crowds surrounded the plant, trying to keep out employees willing to work, some of whom were newcomers who’d responded to company hiring ads. There were regular scuffles with police, on hand in great numbers to clear a path into the besieged workplace. But the real trouble erupted after employees overwhelmingly rejected a settlement arranged on May 9 by the International’s representative Jack Ross and Local 213 president Angus MacDonald.

Under the proposal, fired workers could reapply for their jobs without reprisal, but they would lose their seniority and there was no guarantee how many would be taken back. The BC Federation of Labour and the Vancouver and District Labour Council (VDLC) also denounced the deal. When Local 213 business agent Art O’Keeffe refused to implement it, he was fired by the Canadian vice-president of the union, William Ladyman of Toronto. The firing of O’Keeffe brought trade unionists and labour leaders from everywhere into the fray.

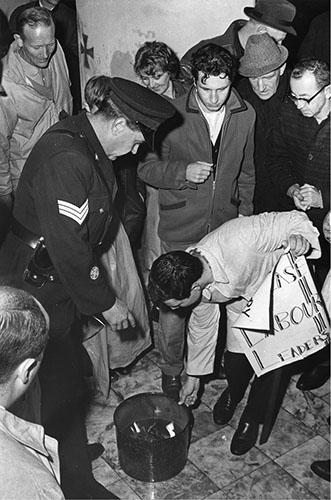

On May 10, the first day of all-out picketing, a mass coughing fit drowned out a sheriff as he tried to read terms of the court injunction to the crowd. Vancouver and District Labour Council secretary Paddy Neale told reporters, “Our intention is to shut down the plant. If necessary, we’ll have another picket line here tomorrow, a bigger one.” The next day, more than three hundred people showed up on the line. Ferocious clashes broke out as dozens of police struggled to guide non-strikers into the plant. More than two dozen picketers were arrested. That night, some angry strikers burst into a Local 213 executive meeting, physically ejected local president Angus MacDonald onto the street, demanded strike pay and began an occupation of the union’s premises. “This is our hall,” they told a Vancouver Sun reporter. O’Keeffe continued to report for work.

On May 16 a high-powered group of labour leaders, including Syd Thompson of the VDLC, BC Fed vice-president Jack Moore and Jack Ross of the IBEW, met with Lenkurt executives to try to resolve the volatile dispute, but the company refused to budge from the May 9 deal. “We pointed out the labour movement would never tolerate those terms,” Thompson said after the meeting. “[But] they’re a hard-nosed outfit.” Ladyman ripped the BC Federation of Labour for interfering in IBEW matters. “The International has not asked for help from the Federation,” he said. “We are quite big enough to settle this for ourselves.”

With the company standing firm, court injunctions still in place and IBEW brass opposed to the strike, the fired workers were up against it. On May 28 they voted to return to work under the pact they had earlier rejected. There was a price to pay: more than seventy-five workers were not rehired, including all members of the shop steward committee, while returnees lost their seniority.

Then the IBEW handed out its own discipline. For defying the International, O’Keeffe was suspended for fifteen years and Tom Constable, a future mayor of Burnaby, was fired as assistant business manager of the local and suspended for three years. Rank-and-file firebrands Les McDonald, Jess Succamore and George Brown were suspended from the union for thirty, twenty-five and fifteen years respectively.

After that, the courts had their turn. Fifteen workers were fined a total of $3,100 for contempt of court. BC Supreme Court Justice James MacDonald then targeted Paddy Neale, IWA local vice-president Tom Clarke, Boilermakers leader Jeff Power and Art O’Keeffe for jail time. Neale and Clarke got six months, O’Keeffe four months and Powers three months. Newspaper photos showed Neale and Clarke being led off together to prison, ruefully holding up their handcuffs for photographers.

The bitter Lenkurt dispute, ending in such dispiriting defeat, was a turning point for those dissatisfied with the lack of Canadian autonomy in some international unions. More union activists became convinced, like those in the PPWC, that something had to be done to wrest Canadian control from international unions in the country. Shortly after the IBEW announced its suspensions, those suspended or not rehired held a meeting at the Boilermakers Hall that was also attended by officers of the BC Federation of Labour. They expressed sympathy and disappointment that their just cause had not prevailed.

After they left, stirred by their sentiment, Les McDonald stood up and proclaimed, “What we need is a new Canadian electrical workers’ union!” The meeting enthusiastically embraced his idea. On November 6, 1966, seventeen trade unionists gathered to form the Canadian Electrical Workers, with George Brown and Jess Succamore taking leading roles. Like the PPWC, the CEW adopted a constitution emphasizing rank-and-file control, paying no full-time officer more than the top rate earned by members of the union and hanging its hat on Canadian nationalism. “[This was] made in Canada by Canadians and only Canadian workers can change it,” its founding document stated.

Kept alive financially by secretive membership dues from dissatisfied IBEW members, the CEW launched its first raid against the International early the next year, signing up a majority of workers at Phillips Cable. After spending months scrutinizing the application, the Labour Relations Board ordered a vote. The CEW’s narrow 57–50 victory was the beginning of a long presence in BC by the independent Canadian union, which soon aligned with the Winnipeg-based Canadian Association of Industrial, Mechanical and Allied Workers (CAIMAW). CAIMAW was particularly prominent in the 1970s and 1980s, waging a number of long, hard-fought strikes at BC mines amid a series of acrimonious, often successful raids against locals represented by the United Steelworkers of America. The union proved a catalyst in the drive for more Canadian autonomy within international unions and the eventual, uncontested severing of Canadian members from some of the country’s leading international unions.

There was no such trouble within the IWA, a model of how an international union should work, at least once its communist leaders had been rooted out. While divisions remained over the union’s new moderate leadership, wages, benefits and membership continued a steady rise, though not equally. IWA mills in the Kootenays and Okanagan consistently fell short of gains won by the union’s more powerful coastal locals, who liked to kid their Interior cousins by calling them “jack pine savages.” By the end of a poor three-year contract that ran out in 1967, the IWA’s five thousand members in the southern Interior were earning fifty cents an hour less than their counterparts on the coast for doing the same job. Their bargaining clout was hamstrung by a contract that expired two and a half months after the coastal master agreement. Members decided enough was enough. They determined not to accept any agreement minus wage parity with the coast and a common expiry date.

When the mill owners refused all entreaties by the union’s negotiating committee, workers walked out in the fall of 1967. The strike turned into one of the IWA’s most epic battles, lasting 224 days and catapulting a tall, outspoken tradesman into the beginning of a high-profile union career that made him one of the most recognizable individuals in the province for more than thirty years. Jack Munro was then thirty-six; he had grown up in poverty in Alberta and drifted to the BC Interior, where he worked on the railroad and as a welder at Kootenay Forest Products in Nelson. In a few years, Munro’s leadership abilities, his passion to represent those on the job, and his penchant for reaming out management in the same salty, oath-laced language that prevailed in the bar and in the workforce had made him job steward, plant chairman and then a full-time local business agent for IWA Local 1-405.

The local was soon awash in a flood of injunctions, ordering picketers to stop building fires on logging roads to halt log deliveries. The IWA responded by picketing a mill represented by another union. When their members crossed the picket line, Munro unleashed a torrent of abusive language on them. As affidavit evidence for their injunction, company officials wrote down what he said. Feeling the language was too blue for a public courtroom, the judge reviewed the evidence in his private chambers. At one point, as recounted by Munro in his vivid memoir Union Jack, he burst out to the chastened woodworker, “Jesus Christ, Munro, this is unbelievable.”

It was a hard slog for the strikers and their families. To help them through the winter, the union brought in truckloads of potatoes. Afterward, Munro paid tribute to the “guts and determination” of the women involved, both in the home and on the line, to help maintain the strike. At one mill, where there were rumours of trouble, women picketers locked arms outside the plant gate. Inside their purses were rocks and cans of hairspray, just in case.

Exasperated by the union’s determination to stay the course, Kootenay Forest Products announced its intention to resume production by advertising in the local Nelson Daily News for strikebreakers. Munro opted for a show of union force down the main street of Nelson. A famous photo of the ensuing march shows a lean, almost-boyish Munro in his trademark jacket and tie, leading hundreds of workers toward City Hall. There, he warned the mayor to see that no scabs were hired, or else. The company got the message, and the mill stayed shut. The bold march was a masterstroke. Not only did it head off the use of strikebreakers, it boosted morale and gave the strikers renewed purpose. Through the winter and into the spring, the five thousand strikers remained strong, supported by $100,000 a week in IWA strike pay. Backing from the public was solid too. The beer parlour at the Lord Nelson Hotel became a union hangout at night, where locals were always ready to buy strikers a round.

After seven months, the companies began to buckle. They offered the IWA close to wage parity, although no change in the contract expiry date. When union negotiators rejected the offer, the government ordered the IWA to put it to the membership for a secret ballot vote. Despite the breakthrough on wage parity, hardened union members gave a resounding thumbs-down to the company proposal. The margin was even larger than their original strike vote.

“That incredible ‘no’ vote won the strike for us,” Munro remembered. “The employers knew we were serious.” Shortly afterward, the union had a deal, getting to within fourteen cents an hour of parity with the coast and an expiry date of June 30 a mere sixteen days shy of the coastal contract. After one of the longest strikes in its history, and forking out more than $3 million in strike pay, the IWA had won a clear victory. No one was affected more than Jack Munro himself. He learned the responsibility of leadership.

“That strike completely changed me,” Munro said in Union Jack. “I had five thousand people really dependent on my decisions. They were giving up everything because of the decisions I was making.” In a candid revelation, Munro said he had to work “really really hard at not screwing up, because it wasn’t just me I’d be screwing up, but a whole lot of other people.” After that, Munro was ambitious for advancement. “I didn’t see myself going back to chasing burnt-out yard lights or settling small grievances,” he said of life as a business agent. The next year, he moved to Vancouver as third vice-president of the union, and in 1973 Munro was elected head of the fifty-thousand-member organization, drawing a salary of $18,000 a year.