12. Bad News Bennett

Outside the conflict raging in BC union halls, a political shock loomed that was to consume and bedevil the province’s labour movement for the next two decades. After ten years in office, the Liberal-Conservative coalition government was fraught with tensions that could no longer be smoothed over. The two parties went their separate ways to fight the next election in 1952. Still worried about the steady strength of the CCF, however, coalition masterminds imposed a transferable ballot, which took into account second and even third choices until a candidate had a majority of the votes cast. They estimated that most people’s first and second choices would be split among the Liberals and Conservatives, keeping the CCF out of office. They didn’t foresee the unexpected appeal of an upstart Social Credit Party.

Tapping into a strong mood for change, Social Credit was many voters’ second choice. After a month of complicated calculations on the electoral abacus, the final totals stunned the province. With 31 percent, the CCF had the highest popular vote. Social Credit garnered 27 percent, the Liberals 23 and the Conservatives 17 percent. But the transferable ballot gave the Social Credit Party nineteen seats, one more than the CCF. The Liberals had six seats, the Tories four and independent labour candidate Tom Uphill had once again captured Fernie, as he had in every election since 1920.

Once confirmed as Social Credit party leader and premier, former Conservative W.A.C. Bennett parlayed BC’s polarized politics into a historic string of electoral triumphs, forever campaigning on keeping the socialists out of office. William Andrew Cecil Bennett was an ambitious, politically astute appliance store owner from Kelowna driven to open up the province with new roads, big dams and an expanding resource sector. With his customary eloquence, esteemed political writer Bruce Hutchison summarized W.A.C. Bennett’s stamp on booming British Columbia in the Vancouver Sun: “The fixed neon smile, bustling salesman’s assurance, ceaseless torrent of speech, undoubted talents of a small-town hardware merchant writ large and a certain naïve, boyish charm are … the emblem and hallmark of a new province.”

But Bennett and Social Credit were bad news for the province’s trade unions. The new government was dominated by an outsider’s spirit of unrestrained free enterprise that worshipped profits and the bottom line and hated anything that smacked of unions or socialism. The labour movement soon found itself locked into long, bitter combat with a government that made its battles with the coalition benign in comparison.

Ironically, perhaps, given the forces grouped against them, the 1950s and 1960s were also good times for BC’s organized workers. Apart from bashing labour, Social Credit fanned the province’s expanding economy with its all-out building program. Well-paying union jobs abounded. In 1958, unionization hit an all-time high, never to be surpassed, of 53.9 percent of the workforce. In reaching this plateau, unions were also aided by widespread adoption of the so-called Rand formula, which resolved dues check-off as an issue after more than half a century of contention. The formula compelled all members of a bargaining unit to pay dues regardless of whether they belonged to the union.

Despite hostility from government, corporations and the courts, the need for workers gave unions good leverage at the bargaining table. In addition to healthy wage gains, unions began to hone in on fringe benefits, winning more paid holidays, better overtime pay, disability provisions, pensions and other improvements. But this did not bring labour peace. Industrial relations under Social Credit were to be marked by confrontation, jailings of many union leaders and class bitterness.

After winning a strong majority in the 1953 follow-up election, Social Credit brought in its first labour legislation a year later. Bill 28 set the tone for all the years the Socreds were in power. Under the Labour Relations Act, powers of the courts and the labour minister were enhanced, those of the Labour Board curtailed. There were new restrictions on strikes and heavy penalties for contravening them. “[Bill 28 brought] industrial relations more into the political sphere,” observed labour historian Paul Phillips. They were to remain there for a long time.

Setting aside their differences, more than three hundred delegates from CCL and TLC affiliates gathered in Victoria to protest Bill 28 and lobby MLAs for changes. One of the delegation’s strongest demands, prompting some to call for a general strike, was an end to ex parte injunctions, which had become such a boon to strikebound employers. At the very least, unions contended, both sides should be heard before any injunction was issued. The government ignored them.

One of the more egregious examples of injunction injustice befell Tony Poje, business agent of the IWA’s Duncan local. During the union’s big coastal strike in 1952, Poje oversaw picketing of a bridge leading to a dock in Nanaimo that prevented union dock workers from loading lumber onto a waiting cargo vessel. The ship owners quickly obtained an injunction, ordering the picketers to cease and desist. The next day, two hundred angry picketers showed up to keep the longshoremen away, ignoring a sheriff’s reading of the injunction and copies posted on the bridge. Six days later, the company summoned the longshore crew a second time. Again the injunction’s order was read out by the sheriff and again IWA picketers thronged the bridge. Poje was charged with contempt of court.

Before his case could be judged, however, the strike ended. As part of the settlement, companies petitioned the court to drop the charge against Poje. The chief justice of the BC Supreme Court, Wendell Burpee Farris, paid no heed. Declaring that defiance of court injunctions could not be bargained away, he sentenced Poje to six months in jail. Union members showed their appreciation of their business agent’s sacrifice by electing him president of the local even while he was locked up. (Three years later, Tony Poje switched to management, and was regularly heckled by union negotiators whenever he showed up on the company side of the bargaining table.)

As unions’ pursuit of better wages and worker rights accelerated, health and safety had tended to take a back seat, despite a growing toll in workplace tragedies. Yet some unions, with the backing of CCF MLAs, did keep up a steady outcry over such basic matters as adequate compensation for injured workers, better pensions for widows of husbands killed on the job and independent medical reviews to consider appeals of denied claims.

In 1949 Gordon Sloan, the chief justice of the Court of Appeal, was appointed to head a Royal Commission on workers’ compensation. By then Bill White of the Marine Workers and Boilermakers Union had made this a personal cause. He began fighting back on individual cases where he felt the Workmen’s Compensation Board had made a particularly bad decision to deny a worker’s compensation claim. Gradually, White acquired a grasp of medical matters, along with a group of doctors he could rely on for unvarnished opinions.

The Boilermakers president prepared for commission hearings for months. He spent days on the witness stand, detailing more than forty individual cases in which workers had suffered disabilities but been denied compensation. He called eighteen doctors, including eight medical specialists, to supporthis contention. “We were setting out to show that the board was absolutely rotten,” White explained. “Our basic demand was an appeal board where a fella could go to some outside authority and have his case reexamined, if the Board rooked him.” Dissatisfaction with the board was so rife, two years of hearings were needed to accommodate the hundreds of fed-up workers and many doctors who wanted to air their complaints.

As part of his comprehensive report, Justice Sloan urged the establishment of medical review panels, as advocated by White and other trade unionists. Unfortunately, his report came down shortly before the pivotal 1952 election, and the recommendation was left to the Social Credit government to implement. To White’s dismay, instead of instituting full-fledged review panels, the Socreds tinkered with the concept. Only after yet another Royal Commission in 1966 were effective and viable medical review panels put into place. White was also critical of the government’s attempt to head off complaints by appointing a form of compensation ombudsman, which he termed “about as much use as a pocket in your underwear.”

Benefits to workers were improved, however. Social Credit agreed to Justice Sloan’s call for higher compensation, better widow pensions and improved travel and therapy subsidies. Further, after considerable political pressure, the government made the increases retroactive to the start of the Royal Commission. “In the first year, monies paid out to BC injured workers by the Compensation Board increased by three million dollars,” White recalled with pleasure. While the outspoken trade unionist was hardly the only advocate on these issues, his leadership showed how one person can make a difference on an issue that gets few headlines but affects thousands of workers.

Despite the best effort of White and other advocates, however, the WCB maintained its regimen of denial. If the board could find a reason to shortchange or reject a pension to an ailing worker, it did. Nothing illustrated the board’s stringent approach more than its attitude toward the deadly mining disease of silicosis. Its hard-heartedness burst into public view in 1956 thanks to a courageous personal crusade by Bea Zucco, whose husband, Jack, was slowly dying of the disease. Although his condition was first diagnosed in 1949, the board repeatedly denied his petition for a pension. The WCB based its decision on X-rays showing he was suffering from tuberculosis, not silicosis. The board ignored the fact that tuberculosis often afflicted victims of silicosis and overshadowed its evidence in the lungs. A series of outside doctors, including a specialist in Bellingham, reaffirmed his silicosis, but the WCB continued to rule “no evidence.”

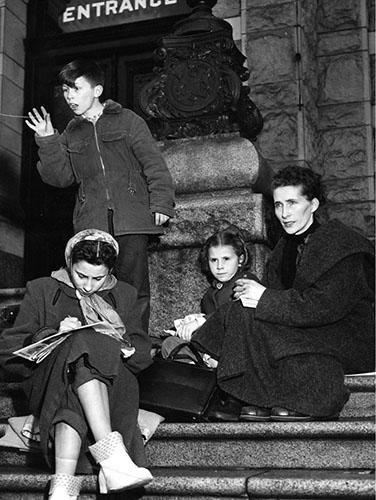

After more than five years of fighting for her ailing husband, on February 23, 1956, Bea Zucco went public. She camped out for a day at the WCB. Four days later, accompanied by three of her children, she staged a sit-down protest on the steps of the legislature in Victoria. The determined miner’s wife captivated the media. Even the Social Credit government was sympathetic. Labour minister Lyle Wicks ordered another review. The WCB didn’t budge. Evicted from her home, relying on donations, Bea Zucco took off on a province-wide “Car Crusade for Silicosis” to raise awareness. On September 11, Bea Zucco became a nationwide cause célèbre when she again camped out on the legislature steps, this time for nine days. Her sign read, ONE SICK HUSBAND. ONE MOTHER—BC PRODUCT. FOUR CHILDREN—ALSO BC PRODUCTS. SEVEN YEARS OF STRUGGLE—A BC DISGRACE!! She won the hearts of the public but could not sway the WCB. Rules were rules.

With Bea holding his hand, Jack Zucco breathed his last in early April 1958. Three weeks later, an autopsy confirmed what the couple had known all along. His lungs had been ruined by “advanced silicosis.” The WCB could not fudge any longer. Expressing “deep regret” over its previous rulings, the board awarded Bea Zucco retroactive compensation of $12,998.87, carefully itemized lest she get a penny more, plus a monthly pension of $75 and $25 for each of her children. After so many years of grinding adversity, Zucco declared it “a hollow victory,” but she was nonetheless proud of her perseverance. “They just can’t do this to ordinary people, not in Canada. I know they can’t,” she said. “I didn’t know anything at the beginning. All I had was the spirit.”

The impact of her indomitable spirit went beyond Bea Zucco’s personal mission. She had exposed the WCB as a cold, unfeeling bureaucracy that shortchanged workers. Unions renewed their attacks on the board at a large special conference, slamming its use of “rigid and legalistic formalism” to reject legitimate claims by injured and ailing workers. Qualifications for silicosis pensions were finally overhauled, ending their sole reliance on X-rays and providing suffering miners like Jack Zucco the benefit of the doubt.

Concurrently, a sea change in attitude was taking place among the country’s trade unions. The more governments rolled back labour’s wartime legislative gains, the more labour realized they could only fight back effectively by calling off the historic conflict between craft and industrial unions. It happened first in the United States. Unions headquartered there had long played a dominant role in Canada’s labour movement, as most workers considered the border irrelevant to their struggle against the boss. Positively, American-based CIO unions spurred the great industrial organizing drives of the 1940s. Negatively, the bitter split between the AFL craft unions and the CIO industrial unions spilled over into Canada, resulting in two national union organizations, the craft-dominated Trades and Labor Congress and the Canadian Congress of Labour, bastion of industrial unions. In BC, the rift compromised solidarity on a growing number of issues as Social Credit fastened its grip on the province.

Under far heavier fire from anti-union forces in their country, US unions realized their rivalry was hurting no one but themselves. In 1955, the AFL and CIO patched up their deep divisions and made peace. The newly merged AFL-CIO claimed a membership of fifteen million workers. Once their merger was complete, the way was open for labour unity in Canada. Facilitated by a no-raiding pact, ongoing talks between TLC and CCL leaders culminated with the formation of the unified Canadian Labour Congress in April 1956. More than a million Canadian workers, representing 80 percent of the country’s trade union membership, belonged to union affiliates of the new national organization.

Unity followed in British Columbia as well. Rival local labour councils merged across the province, and the founding convention of the third reincarnation of the

BC Federation of Labour, with craft and industrial unions together for the first time, was held in Vancouver in November 1956. They united around a socially progressive platform calling for, in addition to extensive labour reform, universal health care, post-secondary colleges across BC and nationalization of BC Electric. The exercise was not without rancour. Some unions stayed on the outside, including the United Mine Workers, several rail unions and the BC Teachers’ Federation, which decided it was more a professional association than a trade union. Also missing, of course, were the unions that had been tossed out of the CCL and TLC for their communist leadership.

Politically, the industrial unions were big on supporting the CCF, the craft unions not so much. There was also tension over how activist the Federation should be. The more autonomous-minded craft unions initially preferred leaving political action to individual unions, but they too had been affected by operating in a province with a long history of union resistance. It did not take long for the new BC Federation of Labour to resolve these matters and emerge as the most effective, hands-on, centralized labour organization in the country. With unions under persistent attack from hostile employers and government, the Fed was soon taking a new, heightened interventionist role in the province’s labour disputes. Strike co-ordination, beefed-up picket lines, “hot” declarations proscribing union members from handling goods produced by a strike-bound company and threats of a general strike became regular weapons in the Federation’s arsenal.

There were changes in the public sector too, particularly for the BC Government Employees’ Association (BCGEA) as it tried to grapple with the tight-fisted Socreds. The union was led by Ed O’Connor, a Dublin-born son of a soldier who had been working for the government as a court registry clerk since 1928 and delighted in wearing Homburg hats. His mettle was tested almost from the moment W.A.C. Bennett came to power in 1952. For the next twenty years, Social Credit policy was unyielding: keep government employees under thumb, with no say in determining their wages and working conditions.

Within two years, O’Connor was complaining that the Socreds had “all the earmarks of fascism, Nazism and communism.” As he did whenever he felt that the BCGEA was getting uppity, Bennett punished the association for O’Connor’s remarks. In a fit of pique, he cut off all meetings with the organization, vowing no resumption until the BCGEA had leaders more akin to his liking. Thus began the annual ritual of government unilaterally ordaining wage increases for the coming year. There was no collective bargaining, not even talks. Instead, Bennett notified employees of their modest annual raises through the media, without a word to the association. The BCGEA and the provincial Civil Service Commission made competing cases to the government through written presentations, dubbed by union historian Bruce McLean as “the battle of the wage briefs.” Even commission head Dr. Hugh Morrison admitted the process was nothing more than “legalized paternalism.”

The association did manage to gain a five-day week in 1955, plus improved vacations and sick pay. But pay hikes remained stuck around 2 percent a year, well below those won by government employees in other provinces and leaving them ever further behind wages in the private sector for similar work. It seemed as if the words of civil service commissioner W.E. MacInnes to a small gathering of government workers back in 1919 were still relevant nearly forty years later: “Blessed are they that expect little, for they shall not be disappointed.”

In 1957, fed up with their low wage rates and armed with an 89 percent strike vote, the BCGEA threatened to strike for the first time. Taken aback by their resolve and cognizant of public support for underpaid civil servants, Bennett agreed to bump up their small raise, albeit minus six months’ retroactivity. That set the stage for 1959, when the BCGEA took on the government in earnest. Demanding a 10 percent wage increase and full collective bargaining rights, the association called a strike for March, Friday the thirteenth. Once again, on the eve of a walkout, the government wavered, doubling its previous wage increase to an acceptable 7.5 percent. But there was no give on collective bargaining, so the association went ahead with its first-ever full-scale strike.

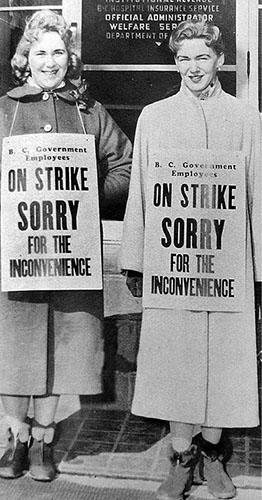

At 7 a.m., carrying signs that read “On Strike. Sorry for the Inconvenience,” thousands of union members began picketing government buildings across the province. Three and a half hours later, the government had an injunction ordering pickets to stop “watching, besetting or picketing” any of its premises. Half an hour after that, the association complied. The historic strike was over. O’Connor said there was simply not enough solidarity to maintain what the Vancouver Sun called “the most genteel strike in British Columbia labour history.” “A few people crossed our picket line, but we were too polite to call them scabs,” said first-time striker Dorothy May.

Notwithstanding the Sun’s description, the sight of nattily dressed men and smiling women in their long coats and fur-trimmed boots wearing picket signs enraged blustery highways minister Phil Gaglardi. No government in a free country could give its employees full union status, he bellowed. “[Association leaders] are [only] interested in power so that they can abuse those civil servants, use them as pawns, [and] take over from the elected representatives.” A few days later, the Socreds passed an amendment to the Constitution Act making it illegal to picket government buildings. Later, they explicitly banned civil servants from striking at all.

Despite the strike’s speedy end, association members were energized by having stood up to the government, for however short a time. “It was a sad task convincing [some] members that the strike was over in four hours,” said Roy LaVigne, an employee at the Essondale (later Riverview) mental health facility. “But we had closed them down. You couldn’t get married, buried or buy a bottle of booze. If there is a next time, pray God that the union tells them to stick their injunction where Paddy put his sixpence.” Nancy Hamilton, who went on to serve many years as the organization’s treasurer, said the strike was an emotional experience for members at the Woodlands psychiatric facility. “It was a miserable morning, snowing and blowing. We were all keyed up. It was a disappointment to have to go back in the afternoon,” Hamilton recalled. “But I was relieved, because I had seen some nurses and aides in tears on the picket line, really worried about their patients. There was a lot of heartbreak.”

The previous summer, a horrifying tragedy had befallen members of Local 97 of the International Association of Bridge, Structural and Ornamental Ironworkers. On the hot afternoon of June 17, 1958, the lead crew of ironworkers on the massive Second Narrows Bridge under construction across Burrard Inlet laboured to put one more section of steel in place to complete the last anchored span jutting out from the north shore. Just before quitting time, with a terrifying roar that could be heard all over East Vancouver, the span collapsed, bringing previously built sections of the bridge down with it. In six seconds, seventy-nine men were pitched more than a hundred feet into the deep, swirling water amid a lethal cascade of massive steel girders.

“I went right down to the bottom, right down to the soil. I thought I was gone. Goodbye. Adios,” recalled Norm Atkinson on the fiftieth anniversary of that fateful day. But just the year before, a new safety regulation had required all those working above water to wear a life jacket. Somehow, the veteran ironworker managed to undo the quick release on his heavy tool belt, and his mandatory life preserver brought him to the surface. “As I came up, I remember the water getting lighter. Finally, I hit air. What a wonderful feeling that was.” Atkinson and other survivors surfaced to a scene of horror: maimed, mangled bodies and terribly injured men trapped in the twisted steel and rising tidewater, screaming for rescue. “I saw a hell of a lot of things that day, and I forget nothing,” said Atkinson. “Bodies going by like corks, like pieces of wood. They were your mates, but you couldn’t do anything. It was awful.”

Gordy MacLean remained alive after hitting the water but he was trapped in the cab of his small shuttle locomotive that shunted steel along the bridge. Divers tried frantically to free the well-liked engineer, who was hollering for help as his cab filled with water. One was sixteen-year-old scuba diver Phil Nuytten. As he prepared to make yet another rescue dive, Nuytten looked over to see MacLean’s blond hair floating under the surface. He was gone. Continuing to dive, Nuytten found two ironworkers still upright on the bottom of the inlet, anchored by the weight of their tool belts. When he arrived, he noticed three bodies laid out on the wharf. “By the time I left two hours later, there were twelve.”

Eighteen lives were lost that day, most of them ironworkers. A diver later died during a search for victims, bringing the final death toll to nineteen. Another twenty workers were seriously injured. It was by far the worst industrial accident in Vancouver history. The catastrophe was front-page news across North America. Hundreds showed up at Empire Stadium for an emotional outdoor service. Country star Jimmy Dean and Stompin’ Tom Connors wrote heartfelt songs about the tragedy. The provincial government wasted no time striking a Royal Commission into the disaster, headed by BC Chief Justice Sherwood Lett, a veteran of both world wars with a reputation for no-nonsense jurisprudence.

It did not take long to identify engineer John McKibbin’s inadequately designed falsework as the cause of the collapse. It had buckled under the weight of the outer span. Both McKibbin and his direct overseer Murray McDonald died in the collapse. But why had his mistake not been noticed? In his comprehensive report, Lett found contractor Dominion Bridge guilty of negligence for failing to submit the falsework plans to higher-up consulting engineers and “leaving the design to a comparatively inexperienced engineer, with inadequate checking.” Although he stopped short of citing Vancouver-based Swan-Wooster Engineering, the overall bridge designers, for negligence, Chief Justice Lett singled out the company for “lack of care.” No blame was attached to any of the workers who perished.

The media moved on to highlight the sad state of WCB pensions provided to widows and families of the dead workers: $75 a month for their wives and $25 for each child, amounting to barely a quarter of what their husbands or fathers had earned. Although a public trust fund amassed some extra money, most widows had to find ways to work to provide for themselves and their families.

Since 1994, the collapse has been remembered by renaming the bridge the Ironworkers Memorial Second Narrows Crossing. But few are aware of the dramatic events that followed for Local 97. As survivors returned to the job, Local 97 was locked in tough negotiations with Dominion Bridge. Armed with a strong strike mandate, including a 79–4 “yes” vote among those building the Second Narrows bridge, the union was seeking a wage increase to reflect the dangers they faced on the job, improved travel pay and a ban on using workers imported from neighbouring Alberta. On June 23, 1959, mere days after the first anniversary of the collapse, ironworkers were on strike at Dominion Bridge construction sites across the province.

At Second Narrows, the striking ironworkers left behind an expanse of steel balanced on falsework that was hanging over the road and railroad tracks leading to the “old” bridge farther east, which was still open to traffic. Declaring the overhang hazardous, Dominion Bridge asked the union to allow a crew to finish the span until it was anchored to the next pier. When Local 97 business agent Norm Eddison refused, the company went to court, where the drama really began to unfold. Submitting affidavits claiming the jutting span was a risk to the public, Dominion Bridge sought an ex parte injunction, ordering the ironworkers to resume work until the span was “entirely safe.”

The application came before Justice Alexander Malcolm M. Manson, who had begun his BC legal career in 1906. He had a reputation as an exceedingly prickly anti-union judge who didn’t hesitate to harangue lawyers he found annoying. Without much ado, Justice Manson ordered the ironworkers to return to work on the southern section of the bridge. Although pickets came down forthwith, ironworkers continued to stay away. Referring to company claims that the span was liable to plunge onto the roadway in a small earthquake or other tremor, Eddison asked, not unreasonably, “If the bridge is unsafe for the public, why is it safe for our members?” He avowed he would rather rot in jail than imperil their lives by ordering them back to work.

Justice Manson reconvened the court to consider the ironworkers’ appeal. There, he first clashed with the union’s brash twenty-six-year-old lawyer Thomas Berger, who argued it was not up to a judge to order men on a legal strike back to work. It was the job of the legislature. Berger got nowhere and Justice Manson upheld his injunction. Sheriffs trying to serve copies of the injunction found few ironworkers at home. Eventually eighteen were served, but the site stayed idle. When Manson summoned them to appear before him, none showed up. He ordered their arrests. Berger later wrote in his autobiography, “The judge was inventing his own procedure, because none in the books suited his purpose.”

On July 13, 1959, seven ironworkers finally complied with the angry judge’s summons. Union supporters crowded the courtroom, jeering the judge when he threatened Berger, later a BC Supreme Court justice himself, with contempt of court for his interjections. Eric Guttman, the first ironworker to take the stand, told Justice Manson he had been instructed by the union to return to work. “But it is a free country and nobody can force me to go to work to build a bridge if I don’t want to.” The judge got much the same answer from the others. In the end, union officials Eddison, Fernie Whitmore and Tom McGrath were fined $3,000 for criminal contempt of court, then hauled off to Oakalla until they paid. Justice Manson also fined the union $10,000 and Guttman $100 for his defiance, a penalty the rank-and-file ironworker described as a badge of honour. The union leaders were soon free, after the BC Federation of Labour raised money to help pay their fines.

George North was not so fortunate. In a jaw-dropping sidelight to the legal furor surrounding the ironworkers, the editor of the Fisherman newspaper was also charged with contempt of court for what he wrote about Justice Manson’s original judgment. Calling the ruling prejudiced and collusive, North’s editorial appeared under the headline, “Injunctions Won’t Catch Fish nor Build Bridges.” For that effrontery, North was fined $3,000 and sentenced to thirty days in prison.

The BC Court of Appeal quashed all fines levied by Justice Manson against the ironworkers’ union and its leaders. The superior court also admonished the judge for his legal threats against Berger. But the jailing of George North was upheld. After the legal dust had settled, a new regulation, clearly motivated by Justice Manson’s judicial vendetta against the ironworkers, compelled BC Supreme Court judges to retire at seventy-five. “Judge Manson was no hypocrite. He hated unions,” wrote Berger. “He was out to get you, and he did.”

After a fifty-day shutdown, Local 97 settled its dispute with Dominion Bridge and work resumed on the Second Narrows Bridge. Almost two years to the day of the collapse, the last linking girder was lowered into place. First across was survivor Norm Atkinson. “Atta boy, Norm,” a workmate called out. Vancouver Sun reporter John Arnett wrote, “Atkinson’s grimy face creased into a wide grin, as he called back, ‘Bring on the cameras.’” It was the most bittersweet of moments.

There was more to come. As Atkinson strode jauntily across the twelve-ton girder, his local union was anything but united. Not long after the strike ended, the local’s international overseers came riding into town. Fed up with criticism from the local, the International charged Eddison, Whitmore and McGrath with organizing an unauthorized strike. After a one-sided hearing that found all three guilty, their punishment was harsher than anything handed down by Justice Manson. Not only were they fired, the three were banned for life from belonging to the union, making them ineligible to earn a living as construction ironworkers. Dismayed by the punishment, Pat O’Neal of the BC Federation of Labour noted the three men had organized “one of the most successful strikes conducted in this province for many years.”

Tom McGrath hadn’t waited for the decision. Calling the hearing against him “a vivid example of international gangsterism,” McGrath simply quit. The feisty, bantam-sized trade unionist had cut his union teeth at the age of sixteen during the Canadian Seamen’s Union strike against Canada’s deep-sea merchant marine fleet in 1949. Coloured by the Seafarers’ International Union’s crushing of the CSU and what had just happened to him in Local 97, McGrath felt it was time for all-Canadian unions, free of international entanglements.

He formed Canadian Ironworkers Union Local 1 to take on the International directly. Sid Stewart (the father of Alan Stewart, who died in the Second Narrows Bridge tragedy) signed on as business agent. A majority of Local 97 members joined up, and McGrath asked the Labour Relations Board to cancel four certifications held by the International, including Dominion Bridge. But McGrath’s dream of a Canadian union foundered on the same shoals of reality as the breakaway Woodworkers Industrial Union of Canada. The International held the contracts, certifications and resources to oppose all attempts by the Canadian Ironworkers Union to secure collective agreements with unwilling contractors. At the same time, open supporters of McGrath’s union found themselves kicked out of Local 97. Some were threatened with violence, although none took place.

Bled dry by ongoing legal battles, Local 1 eventually ceased to function as an effective union. One victory remained, however. Too late for it to make any difference, the courts awarded the Canadian Ironworkers Union $30,000 in damages from the International for its underhanded tactics. After paying off debts, McGrath donated the remaining $2,500 to another independent Canadian union, the Canadian Association of Industrial, Mechanical and Allied Workers.

Meanwhile, the country and the labour movement had a new political party. The CCF was gone. Taking its place was the New Democratic Party, unveiled to great fanfare at a founding convention in Ottawa in August 1961. The result of collaboration between the CCF and the Canadian Labour Congress, the NDP sought to distance itself from the rural roots of the CCF and attract new voters in Canada’s bourgeoning industrial workforce. Tommy Douglas, the long-time CCF premier of Saskatchewan, took over as leader. The BC New Democratic Party was formalized two months later. Carpenter Bob Strachan headed the provincial party with Tom Berger, fresh from his ironworker legal battles, as president. The significant involvement of unions, which now had an official party for the first time, did not go unnoticed. Premier Bennett hastily pushed through a bill banning unions from donating any portion of dues money to a political party.