15. That Seventies Socialism

The BC labour movement entered the 1970s in fighting trim. While court injunctions and anti-labour bills had taken a toll, the province’s trade unions had proven to be durable combatants, regularly winning respectable wage increases at the bargaining table. At 140,000, membership of the BC Federation of Labour was nearly double that at its founding convention in 1956. Although legislative hurdles and an expanding, unorganized service sector had reduced the rate of unionization to 43 percent of the workforce, BC remained the most unionized province in Canada. Its industrial unions were the country’s most consistently militant. Wages in the province’s big industries were enough for a young person without a university education to get a union job, buy a home and comfortably raise a family. A greatly expanded public sector was flexing its muscles too, no longer willing to tamely accept government-prescribed wage increases. The sixties had fostered a mood of rebellion in the land. While union members were hardly part of the Love Generation, they were also no fans of the status quo.

Sensing this increased militancy and noting recent union gains, BC employers stole a leaf from labour’s solidarity handbook. They themselves began banding together into industry-wide bargaining associations to a degree unmatched in Canada. The new kid on the block was the Construction Labour Relations Association (CLRA), which had managed to unite hundreds of independent-minded contractors into one large bargaining unit. Chuck Connaghan, the CLRA’s confrontational head, along with the influential Employers’ Council of BC, urged companies to get some backbone and start standing up to unions. Profits were being eroded by union wage increases, complained council president Tony Peskett.

Amid this polarized environment, employers and unions prepared for 1970. Contracts covering more than one hundred thousand workers in the province’s major industries—forestry, mining and construction—were due to expire. There had never been a bargaining year like it. Reporters from across Canada flocked to BC to cover the pending showdowns. The BC Federation of Labour fired the first shot across the bow, bringing leaders of leading unions together for a closed-door strategy session to plan a first-of-its-kind attempt to co-ordinate bargaining during the coming year. Attendees included the IWA, Pulp Sulphite, the United Steelworkers of America, the building trades and CUPE. As meetings continued, the Fed’s Ray Haynes told The Globe and Mail, “The major purpose is to keep the employers from forcing a settlement on a weaker group. No group is going to settle unless the other group settles.”

To underscore the strategy, Haynes and Pulp Sulphite leader Pat O’Neal accompanied IWA negotiators to their first bargaining session with the forest industry. The companies walked out. When Haynes and someone from the pulp union again showed up for the parties’ second meeting, company negotiators stayed but refused to talk to the IWA. The two sides sat across the table staring at each other, reading newspapers and talking among themselves. Afterward, John Billings, president of the companies’ bargaining arm, Forest Industrial Relations (FIR), said there would be no talks with the IWA “in front of people who are not the direct representatives of the industry or its employees.”

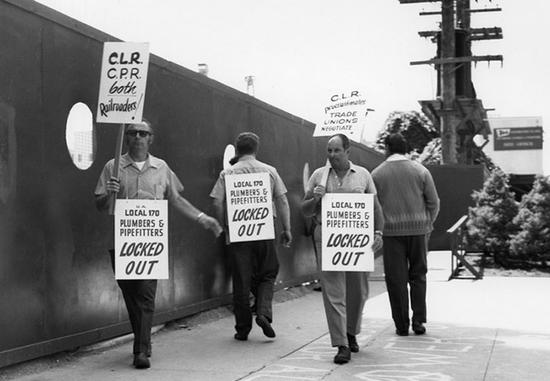

Labour soon had a real fight on its hands. In its initial set-to with the rugged building trades, the CLRA was determined to apply a province-wide settlement to stop a bargaining practice known as whipsawing, in which weaker segments are targeted for union pressure. Those deals are then used to strike equivalent or better terms with the rest of the industry. Partly as a result, BC construction rates were the highest in Canada. After a sprinkling of job action, the CLRA locked out nine of the construction unions across the province, idling twenty thousand construction workers. Others were laid off when many building sites closed down completely. Unions should expect more tough bargaining, vowed Peskett of the Employers’ Council. Companies had been giving in to union demands for too long, he said.

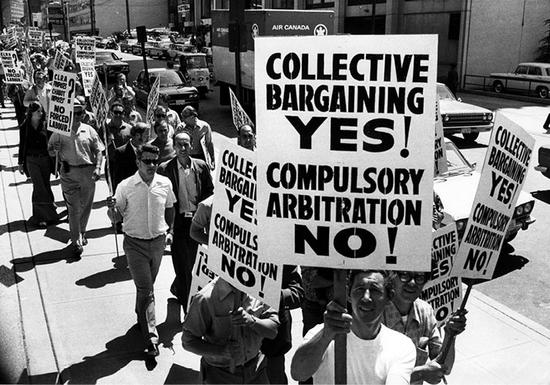

But coverage of all labour stories that spring was missing from the pages of the Vancouver Sun and Province. Union employees at both papers had their own strike. Vancouverites could still read what was happening in a new newspaper on city streets, The Express. The paper was published three times a week by striking members of the American Newspaper Guild. Keeping to the straight-and-narrow approach of mainstream newspapers, The Express proved a resounding success, packed with ads and gobbled up by a public starved for news. Revenue from the paper boosted strike pay and helped pressure the publishers to settle the dispute. A new contract was reached with the assistance of mediators from the Mediation Commission, accepted voluntarily by both sides. The deal confirmed labour’s position, said Ray Haynes, that skilled mediation rather than compulsion was the way to settle difficult strikes.

In the public sector, the BCGEU’s new general secretary John Fryer irritated the Bennett government to no end. With admirable cheek, he began sending out the government’s mandated wage increase to the membership for ratification, even though the terms were fixed. Protests multiplied. On one memorable occasion in the fall of 1969 that made news across Canada, the union hired a Cessna airplane to fly over the legislature towing a banner reading “Drop us a line, Mr. Black. —BCGEU.” The message referred to Wesley Black, cabinet minister for the public service, who continued to ignore all missives from the union.

The government’s long mean-spirited treatment of its employees had welded them into a strong union, far removed from the cap-in-hand association of the past. Victoria Times labour reporter Roger Stonebanks noticed the difference at the union’s 1971 convention. “[The 1965 convention] seemed a cross between a social club and a debating society, held together as much by charter flights to the Old Country as anything,” Stonebanks wrote. “[Now] the actions of the delegates are stronger. Speakers urge a militant stance.” Their day was coming.

Soon more labour turmoil surfaced from an unexpected source. The Canadian Merchant Service Guild (CMSG), representing about a thousand officers and engineers on BC towboats, struck for the first time in years in a dispute over staffing requirements and safety conditions. When the towboat companies began running tugs operated by supervisors, the CMSG expanded its picket lines to a number of IWA sawmills and several pulp mills using logs and wood chips transported by non-union tugs. The forest companies went to court, emerging with fistfuls of injunctions against the guild’s broadened picketing. Proclaiming that safety was too important to be decided by the courts, the union defied the injunctions.

“We will not drown one more man or maim one more person because of unsafe conditions,” declared an emotional CMSG president Captain Cecil Rhodes, pointing to the deaths of fifty union members in towboat accidents over the previous ten years. “Make no mistake about it. There’s a lot of us going to jail to change the laws.” The secondary picketing put fourteen thousand IWA members and nearly five thousand pulp workers off the job. With the wide net cast by CMSG pickets, the construction lockout, and a simultaneous strike by staff at hotel beer parlours, BC was a sea of labour trouble.

Emotions were cranked up by large union rallies to support leaders of the Merchant Service Guild as they awaited contempt-of-court convictions. Ray Haynes endorsed their civil disobedience, pointing out that restricting CMSG pickets to company offices would doom their strike. Ed Lawson of the BC Teamsters Union, while not condoning the union’s defiance, said he understood it. “When the courts are abused, when injunctions are used as a bargaining lever by employers, they almost forfeit the right to responsibility from the other side,” Lawson told the Vancouver Sun. The IWA’s Syd Thompson said his members accepted losing work because of guild pickets. “When you’re at war with the boss, there can be no division and no differences of opinion in the labour movement,” he thundered at a boisterous, two-thousand-strong protest outside MacMillan Bloedel headquarters in Vancouver.

As tension grew, Ottawa sent in its top mediator, Bill Kelly. With his assistance, the towboat dispute was settled. But there was a huge price to pay. Supreme Court Justice Thomas Dohm, who had sent Homer Stevens to jail for a year, sentenced the chief union negotiator, Captain Arnie Davis, to six months behind bars. Even more onerous, he fined the virtually penniless CMSG $75,000, the largest fine ever imposed on a union. There were also steep legal costs. Labour leaders were enraged, pointing out that the strike was not over wages but the lives and safety of towboat workers, matters that should have been federally regulated. Even Jack Moore, the moderate president of the IWA, called the courts’ treatment of the CMSG “an orgy of revenge.” Others branded employers’ use of the courts “a campaign of terror.” When the punishment was upheld, labour banded together to pay the record fine on behalf of the guild. The Federation of Labour pledged its East Broadway headquarters as security.

Meanwhile, confronted with a three-month shutdown of the construction industry, the provincial government invoked the Mediation Commission Act in a major dispute for the first time. After a round of fruitless talks in Victoria, BC labour minister Leslie Peterson used his powers under the act to issue a back-to-work order and proclaim compulsory arbitration. When contractors accordingly lifted their lockout, only three of the locked-out unions went back to work. Six building trades thumbed their noses at the back-to-work order, risking heavy fines by maintaining labour’s two-year boycott of the Mediation Commission.

At a special mass meeting, the Federation of Labour pledged total support for the construction workers. As a showdown loomed, the government drew back. Instead of cracking down on the unions’ now illegal strike and putting the matter to binding arbitration by the Mediation Commission, Peterson parachuted himself into a critical round of further negotiations at the Empress Hotel. After eight hours of tense talks, the parties reached an agreement. Striking construction unions would go back to work and the dispute would be put in the hands of an independent mediator. The Mediation Commission was sidelined. In its first big test over the act, labour had prevailed. “We have really ended Bill 33,” exulted Ray Haynes.

The long, hot summer continued. The Pulp, Paper and Woodworkers of Canada had been negotiating at the same time as their Pulp Sulphite adversaries. With talks going nowhere and fearing an IWA settlement would set a wage pattern they didn’t like, close to five thousand PPWC members at the union’s BC pulp mills walked off the job just as the building trades shutdown ended. Even after both the IWA and Pulp Sulphite settled, PPWC members stayed out for eight more weeks, determined to win a better deal than the three-year contract accepted by other pulp and paper workers. Not surprisingly, the industry refused to sweeten its offer, and PPWC members eventually voted to return to work. The failure of their strike did a lot to convince the PPWC that joint negotiations with their rivals seemed the only realistic way to take on the pulp and paper industry at the bargaining table.

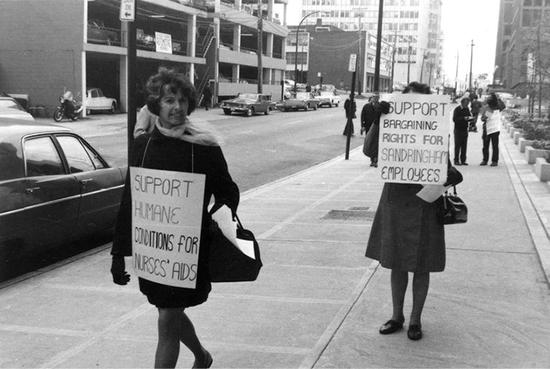

Also in 1970, an exceptionally bitter strike by eighteen hundred members of the United Steelworkers of America shut down Alcan’s vast smelter in Kitimat for three months. Some of the bitterness was directed at the union’s handling of negotiations and a hotly contested return to work with no appreciable increase. The Steelworkers eventually lost their certification to an upstart plant union, the Canadian Association of Smelter and Allied Workers, another of the independent Canadian unions making their mark in the province. Smaller but prolonged strikes dotted the labour landscape as well, including a five-month strike by municipal workers in Penticton and, little noticed at the time, a walkout by women employees at the private Sandringham Hospital in Victoria that turned into the longest strike in Canadian labour history.

Throughout the strife, the BC Federation of Labour was a constant factor: rallying the troops, pressuring employers and government, and ensuring respect for its policies. Intrigued by the extent of union ferment, The Globe and Mail sent its veteran labour reporter Wilf List to take a look. List told his readers there was no labour climate like it. “The reputation of BC labour for militant action has spread far beyond the boundaries of the province,” he wrote. “There is more co-operation among unions than anywhere else in Canada and perhaps North America.” List pointed to the sanctity of the picket line and the effectiveness of “hot” declarations in BC, unmatched, he said, anywhere in Canada.

The war continued in 1971. Teachers got into the act, with the first province-wide strike in their organization’s fifty-four-year history: a one-day action to press demands for better pensions, not for themselves but for teachers already retired. Underlying their action was anger over restrictive policies that capped wage increases while leaving them with class sizes among the largest in Canada. As it had done ten years earlier to the BC Government Employees’ Association for its brief strike, the Bennett government punished the BC Teachers’ Federation. A long-standing clause in the Public School Act assuring compulsory BCTF membership was simply removed, leaving the organization vulnerable to any number of withdrawals. In a raspberry to the government and an impressive show of support for its organization, only sixty-nine of the BCTF’s twenty-two thousand members took the opportunity to opt out.

Accompanied by Bennett tirades that regularly excoriated labour leaders, Social Credit’s record of anti-union legislation was unrivalled in the history of BC. By the time of the 1972 election, the province’s unions were in a virtual state of war against Bennett, his government and BC employers. That year, labour disruptions topped even those in 1970, accounting for the loss of an incredible two and a half million workdays among a workforce of fewer than a million employees. “That is a ratio I have never known to be attained anywhere,” said labour law academic Paul Weiler.

Unions were determined as never before to finally put an end to Social Credit rule. The premier got a taste of what was to come during his annual cabinet tour of the province that spring. Locked-out/striking construction workers, furious at another back-to-work order issued by the Mediation Commission, showed up to vent their anger at many of Bennett’s campaign-like stops. In Kamloops, they drowned out the opening of a new vocational school with a cascade of boos and catcalls. As Bennett left the event, surrounded by police and protesters, his famous smile frozen in place, one construction worker jeered loudly, “Keep smiling, Wacky!”

The melee was far worse at the Royal Towers Hotel in New Westminster, where the tour wound up. Hundreds of fired-up building trades members gathered outside. Many carried protest signs nailed on two-by-fours. Bennett was escorted in by a back entrance, but cabinet ministers had to make their way through an intimidating gauntlet of placards. Several ministers were hit on the head. Agriculture minister Cyril Shelford suffered a broken collarbone when he tried to deflect a placard aimed at cabinet minister Isabel Dawson. Amid cries of “Seig Heil!” and “Get that Mussolini!” protesters pounded the car of high-profile minister “Flyin’ Phil” Gaglardi.

It was an ugly scene. But two decades of attacks from government, the courts and anti-union business hawks had left labour tempers short and civility on hold. The Mediation Commission’s arbitrary interference in the ongoing construction industry dispute was the last straw. Shortly after the New Westminster dust-up, the RCMP raided a number of construction union offices for evidence that leaders had counselled defiance of the commission’s back-to-work order. The raid prompted BC Fed secretary-treasurer Ray Haynes’s cutting comment, “There is no way you can build skyscrapers with search warrants.” Criminal charges were soon laid against a dozen leaders of the building trades.

Fresh from its one-day strike over pensions, the BCTF set up a cash-flush Political Action Committee to oust Social Credit. Friendly with Bennett in the past and no friend of the Federation of Labour, BC Teamsters Union leader Ed Lawson had nonetheless seen his union burned by the Mediation Commission as well. “In every case, our membership wound up being penalized [by the commission]. Stabbed in the back might be a better explanation,” said Lawson. He too pledged an all-out effort to get rid of the Socreds.

The labour movement unleashed hundreds of volunteers in ridings across the province, flooding NDP coffers with cash. Yet party strategists were spooked by Bennett’s past success in linking them with “big labour.” Dave Barrett, who had taken over as leader following the Berger election debacle in 1969, persuaded Ray Haynes to withdraw as the party’s prospective candidate in Vancouver Burrard. Trade unionists were urged to keep a low profile. Many top union organizers found themselves shunted to the seemingly hopeless North Vancouver campaign of the BC Fed’s political action director, Colin Gabelmann. “We had twenty-five union types working for me full-time. They were bumping into each other,” Gabelmann recounted, laughing at the memory. “I had one guy who did nothing but make sure I got fed, my shoes were shined and my shirts ironed and clean. These were people not welcome anywhere else. And some were pissed that Ray Haynes had been shut out [in Burrard].”

But Barrett ran a masterful campaign. He hammered home his ringing cry, “Enough is enough!” with gusto and humour at every stop. The seventy-one-year-old Bennett seemed hesitant and out of touch, his fire gone. When the ballots were counted that unforgettable night of August 30, 1972, Social Credit was out, reduced after twenty years in power to just ten seats, done in by a 5.7 percent increase in the NDP’s popular vote and large numbers of British Columbians who split the “free enterprise” vote by switching to Liberal and Conservative candidates. Barrett and the NDP swept to power, taking thirty-eight of the fifty-five available seats. Even Colin Gabelmann won. The province had its first socialist government.

After weathering so many bitter electoral losses and government attacks, the labour movement saw its party in power at last. Amid joyous scenes at the NDP’s frenzied election headquarters in Coquitlam, Rudy Krickan of the Retail Clerks’ Union, a veteran of party campaigns since the 1930s, spoke for many when he told a reporter, “This is the greatest day of my life.” Despite a difficult relationship with Barrett, who was uncomfortable with labour’s ties to the NDP, union leaders felt their time had come. They looked forward to not only the overturning of Social Credit legislation but to laws that would allow unions and their members to expand and prosper. “For the first time I had the feeling we had a government we could work with,” said Haynes years later. “I felt we could bury the hatchet.”

Matters began well. During a quickie session that fall, the hated Mediation Commission and its compulsory arbitration powers were axed. The minimum wage was raised from $1.50 an hour to $2.00, with a commitment to $2.50 in 1974. Wage caps on teachers were eliminated and compulsory BCTF membership restored. And all charges against construction union leaders for defying the Mediation Commission’s back-to-work order were dropped.

Then the bombshell hit. Bill King, the new minister of labour, announced the appointment of a three-person commission to propose major revisions to the province’s outmoded labour code. None of the “three wise men,” as they were soon labelled, came from organized labour. Instead of the pivotal role they anticipated, unions were told they could present their views at public meetings like everyone else. For a process that would have such a profound effect on their members, this was a blow. “You help get the government elected. You think you’re partners,” explained Ron Johnson, who worked for the Fed in those days. “Then the three wise men are appointed. There was huge friction, right off the top.”

But this friction was not initially apparent when King introduced the NDP’s labour code in October 1973. It was a breathtaking document, detailing the most progressive industrial relations system in North America. For the first time anywhere, jurisdiction over picketing was taken from the courts and given to a newly powerful Labour Relations Board. There would be no more speedy ex parte injunctions that had stymied so many strikes and sent union leaders to jail. New rules facilitated union organizing. Employer hands were now tied during sign-up campaigns, and unions would be granted automatic certification without a vote if a majority of the workforce inked membership cards.

Police, firefighters and hospital workers were given the right to strike, with an option of binding arbitration without employer consent. Companies could be denied relief over a wildcat strike if the LRB determined they did not have “clean hands.” Professional strikebreakers were outlawed, while an innovative section on technological change gave unions the right to appeal to the LRB if significant mid-contract changes to existing work practices took place. After the dark decades of Social Credit, the sun seemed to be shining on organized labour in BC.

But among all the advances that were the envy of other unions across Canada, there were initiatives that labour leaders resented and fastened on. Many opposed a clause allowing union members to opt out for religious reasons. “Anti-union!” stormed Marine Workers’ head William Stewart in his thick Scottish burr. “We are now going to be asked to subsidize some other form of organization, whether it’s the Christian Labour Association or those funnily dressed people [Hare Krishnas] who make strange noises outside the Bay.” Nor did labour embrace an intriguing section allowing unions to seek binding arbitration to settle first contract disputes. That arose from Bill King’s frustration over his inability to settle the ongoing strike at Victoria’s private Sandringham Hospital, then into its fourth year. CUPE had managed to organize the mostly female workforce, but could not get the millionaire owner to negotiate an agreement. “It was tragic, totally unfair,” King reflected. With the code looming, the strike was finally settled after the twenty-eight strikers had spent a record thirty-nine months on the picket line. No matter how worthy its intention, however, organized labour refused to condone any use of binding arbitration.

But the biggest concern was picketing. Most union leaders preferred fighting in the trenches of industrial warfare without restraint. To their dismay, the code restricted their right to set up secondary pickets wherever they felt they were justified. Jurisdiction over secondary picketing was given to the LRB, and it was not wide open. “They were really heartbroken, because the one thing they wanted was the right to secondary picket,” said Ron Johnson. Several hundred union representatives journeyed to Victoria to lobby the government to change the code, but Bill King held firm.

“The BC Fed took the position that they had supported our party for years, which was true,” said King in 2008. “And labour had suffered from inequality and unfair treatment under a pro-management government. I was sympathetic to that argument, but I wanted to strike a balance.” Three NDP backbenchers—Gabelmann, Harold Steves and Rosemary Brown—voted against various sections of the code, but it sailed through the legislature after a remarkably rancour-free debate.

Despite the Fed’s unhappiness, organizing boomed under the code. Unionization rose to 44.9 percent of the workforce. The NDP also passed a fair-wages act, ensuring that union rates were paid on all public contracts. And although the Federation was skeptical about the new Labour Relations Board and its powers, the choice of Ontario legal professor Paul Weiler to chair the landmark tribunal turned out better than anyone could have foreseen. His measured decisions and judicious use of the board’s mediation powers gave unions the fairest treatment they had ever received. Under Weiler, the board specialized in practical judgments based on the nuances of a specific problem, a huge advance over “letter of the law” rulings from the courts.

There were also momentous changes to workers’ compensation and workplace health and safety. For the first time in Canada, independent boards of review were established to rule on Workmen’s Compensation Board appeals, ending years of having them decided by the compensation board’s own officials. The boards of review also published their decisions, as did the WCB, another Canadian first. Disability and widows’ pensions were hiked to fairly reflect loss of earnings and cost-of-living increases. Compensation for injured workers was raised too.

The ridiculous practice of giving companies notice of WCB inspections was ended. Worker representatives were allowed to accompany inspectors on their tours. More inspectors strengthened enforcement of WCB orders. The cost of noncompliance with safety measures skyrocketed. Premiums went up for industries found to be consistently hazardous. The definition of occupational disease was broadened. Toxicologists and hearing specialists were hired as part of unprecedented attention given to the complexities of industrial disease. Tougher contamination levels were set in many industries, and safety regulations extended to agricultural workers and fishermen. As a capper, the WCB’s name was changed to the non-sexist Workers’ Compensation Board, reflecting the large number of women in the workforce. Presiding over this sea change was Canada’s leading academic authority on workers’ compensation and health and safety, Terry Ison from Queen’s University in Ontario.

Labour welcomed these far-reaching measures but remained dissatisfied over the labour code. After Ray Haynes surprised everyone by quitting as secretary-treasurer in the fall of 1973 to run a resort on Quadra Island, the fight was aggressively taken on by his replacement, a blunt, tough-talking printer and air force vet named Len Guy. For the next two years, Guy and Bill King, a railway engineer and no pushover himself, locked horns in an ongoing confrontation over NDP labour policies. Guy was a class warrior. “Anybody who tells you he can shake hands and have a drink with the employer is screwing his membership,” he told Marcus Gee of the Province. For his part, as labour minister, King also wanted a good deal for workers. “But I think you have to be viewed as even-handed by the parties,” he later explained. “If you lose that, you’ve lost your effectiveness.” At times it became personal. Once, according to King, the two came close to blows during a private hotel meeting. Neither liked to back down.

The rupture became complete in 1974 when the NDP introduced a series of seemingly innocuous labour code amendments that solidified the LRB’s jurisdiction while strengthening its hand on arbitration matters. To Guy and a majority of Federation officers, the amendments confirmed that the government had no interest in addressing their concerns. After the amendments passed, Guy and president George Johnston told reporters that the BC Federation of Labour had lost confidence in Bill King as labour minister. They called on him to resign or be fired. After a mere two years of government by “labour’s party,” it was a shocking declaration.

A much worse confrontation erupted during the long, hot summer of 1975. Sky-high inflation had driven unions to negotiate unheard-of wage increases. Settlements were coming in with annual increases of close to 20 percent. Employers who resisted were struck. Members of the BC Employers’ Council decided the upward wage spiral had to be squelched. They began with the province’s dominant forest industry. Contracts of both pulp unions and the coastal IWA, covering more than forty thousand workers, expired within two weeks of each other. To harness their bargaining power, leaders of the Canadian Paperworkers Union and the Pulp, Paper and Woodworkers of Canada put aside their deep-rooted enmity to form a common front for the first time. Jack Munro and the IWA, though no fans of the pulp unions, agreed to keep communication channels open.

Far from cowed, the companies welcomed a showdown. In the face of double-digit pay hikes sweeping the province, the industry offered its workers a one-year contract extension with no wage increase at all except for a cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) at the end. It was a convenient time to take on the unions. With a worldwide glut of pulp and thousands of IWA members laid off by a softening lumber market, the bottom seemed to have fallen out of the industry. How much could a strike hurt?

Yet nothing slowed the pulp unions. Outraged by the companies’ provocative offer, brushing aside pleas from the government to give mediator Henry Hutcheon a chance, thirteen thousand workers walked out at all twenty BC pulp mills on July 16. The IWA stayed at the bargaining table. But a month later, sixteen thousand of its members were off the job anyway, idled by the ongoing industry slowdown and fallout from the pulp strike.

Hutcheon’s report to settle the dispute exacerbated the growing divide. The BC Supreme Court judge recommended a two-year total wage boost of $1.55/hour, plus a modest COLA clause. A healthy 28 percent increase on the base rate, it was still below recent BC settlements. The pulp unions rejected it without a vote. CPU leader Art Gruntman scorned the package as “not within a whisker” of the $3.00 an hour over two years they were seeking. The forest companies reluctantly accepted Hutcheon’s recommendations. The IWA was split. Its membership rejected the package by a slender 51.2 percent. Nevertheless, Jack Munro, who had urged a “yes” vote, opted to keep negotiating rather than joining a strike he felt was doomed.

When hard-pressed pulp workers decided to escalate their picketing to IWA operations, festering tensions among the three unions exploded. Munro blasted “super [pulp] militants” for “spreading their mess around” at a time when his union was anxious to keep as many of its members working as possible. Picket signs were ripped up at one mill, and verbal clashes took place at a Federation “unity” gathering. The pulp unions responded by slagging the IWA’s alleged lack of militancy and union solidarity.

The shutdown continued into a third month. In the mill towns of BC, hundreds of pulp workers began applying for welfare to feed their families. The prolonged dispute was also a major financial headache for the NDP government, which relied on the $3-billion-a-year industry for a large chunk of its revenue. Other strikes added to the malaise. Bakers, meat cutters and members of the Retail Clerks’ Union at 125 Lower Mainland supermarkets walked out at the beginning of September 1975, demanding annual wage increases of up to 50 percent. BC Rail was beset by rotating strikes, and a comparatively minor strike by 180 propane truck drivers was starting to disrupt the supply of heat to seniors’ homes on Vancouver Island. As September rolled along, the entire province appeared to be behind picket lines.

In Victoria Bill King, who had spent many frustrating hours to get the warring forestry parties to talk peace, was running out of patience. So was the premier. The government summoned the legislature in early October, ostensibly to order striking propane drivers back to work. Instead, they did the unthinkable. In one stunning swoop, they legislated everyone back to work. Pulp workers, supermarket workers, BC Rail workers and yes, the propane drivers, were given forty-eight hours to put down their picket signs and report for duty. The IWA was lumped in too. In all, Bill 146 covered more than fifty thousand union members, the most sweeping back-to-work edict ever made in the country’s private sector.

Labour leaders were aghast. “My first reaction is one of disbelief,” said Len Guy. “It’s utter strikebreaking,” stormed embittered pulp union leader Art Gruntman. PPWC negotiator Stan Shewaga said members were tearing up their NDP cards. He predicted “total warfare” in the mills. Plans were made to resist. “Rarely in modern times has a government in Canada interfered so brutally in free collective bargaining,” declared Guy. “It’s a complete betrayal of the principles and policies of the NDP and a complete betrayal of the working people who helped elect this government.” He pledged Federation support for any union choosing to disobey the back-to-work order.

There were no takers. Although CPU leaders recommended defiance, union delegates voted 51 percent to comply. Despite the tough talk and leadership outrage, there was not a lot of fight left on the ground. Seeing no point continuing a struggle they felt likely to lose, many rank-and-file workers began heading back to their jobs even before the forty-eight-hour deadline. Supermarket employees were not far behind. The government’s bold action had succeeded, and one of the province’s largest waves of labour conflict was over. But it was a distressing culmination of the strained relationship between the Barrett government and a significant portion of organized labour that had wanted something different from an NDP administration, even though—to outsiders, at least—it seemed the most labour-friendly government BC had ever had.

No such rancour existed in the public sector. Having achieved full collective bargaining rights for the first time, the BCGEU negotiated the largest ever pay increases for government employees, along with a thirty-five-hour workweek. And a spontaneous one-day strike by one thousand Surrey teachers in February 1974, led to a lower pupil-teacher ratio that added close to four thousand teaching jobs over the next five years. The deal resulted from an impromptu meeting between BCTF president Jim MacFarlan and Barrett, who asked what it would take to get protesting teachers off the legislature lawn. An annual two-point drop in the pupil-teacher ratio, responded MacFarlan. Barrett offered a one-point drop. MacFarlan suggested 1.5, and the deal was struck. Such was policy-making in the early days of the freewheeling NDP government.

Three weeks after his back-to-work shocker, Dave Barrett called a snap election. Coincidentally, the BC Federation of Labour’s annual convention took place a few days afterward. When Barrett spoke to the convention, CPU delegates walked out. Others remained seated during several standing ovations the NDP leader received. There was further discord during the convention. Munro harangued the pulp unions for their “useless strike” and the Federation for supporting their “picketing mistakes.” Guy strode to the microphone to defend the Fed. “Put labour first and party second,” he said. “No government could have done what this government did if we had been united.” Local IWA president Gerry Stoney put the best possible face on the acrimony. “The labour-NDP relationship [is still strong]. Bill 146 was labour’s night on the couch.”

A recommendation to continue labour’s support for the NDP was approved almost unanimously. “It was a family fight,” Guy told reporters. “We had a good one, but there’s [no way] we would support anyone else.” Gruntman was a holdout. “I can’t do it,” he said. “I have to put my members’ welfare number one.” But most delegates seemed to agree with IWA delegate Lyle Kristiansen, who reminded them, “Barrett is not the devil incarnate. The only question is: which side are you on?”

After one of the nastiest election campaigns in BC’s tempestuous political history, the NDP retained its share of the popular vote, but a united right returned a reborn Social Credit to power. While the Barrett government was far from perfect, its brief thirty-nine months in office left behind an unsurpassed legacy of progressivism in almost every ministry, including the Agricultural Land Reserve, publicly owned auto insurance, Pharmacare, rent controls and the purchase of two pulp mills and several other enterprises to preserve jobs. The new premier was W.A.C. Bennett’s son Bill, who authored the solidarity of right-wing voters desperate to get rid of the NDP.

New labour minister Allan Williams’s first act was to fire Terry Ison as head of the WCB. On the other side, skilled poker player that he was, Len Guy knew when to hold ’em and when to fold ’em. The game had changed. His first move was to warn Williams not to touch the same labour code that the Fed had criticized so heavily under the NDP.