14. Jailings, a Fired-up Fed and Public-Sector Fightback

In addition to serving as a reminder that BC trade unionists could not be relied on to always follow the dictates of their leaders, the Lenkurt dispute was also a key event in labour’s growing resentment over the use of court injunctions to stifle union struggles. Seeing top Vancouver labour leader Paddy Neale carted off to jail in handcuffs for six months turned the fight against injunctions into an all-out campaign.

Injunctions had multiplied after the enactment of Bill 43 in 1959. The Social Credit government’s new Trade Unions Act was a direct affront to the rights of free speech and freedom of assembly. Banned were not only information and secondary picketing, in which striking unions picket companies doing business with their struck employer, but pamphlets or newspaper ads simply suggesting the public might not want to patronize certain anti-union employers were prohibited as well. Labour leaders never tired of pointing out that long-haired hippies could legally demonstrate outside a restaurant that denied them service, but a union was not allowed to protest outside a workplace that was unfair to its own employees.

Companies wasted little time in taking advantage of the new legislation. Even as strikes declined, the number of court injunctions curtailing union activity shot up nearly 50 percent over the next five years. Eighty percent were issued ex parte, without a formal hearing. So many were coming down the pipe that the Fed’s Pat O’Neal garnered a wave of publicity by wallpapering his office with copies of injunctions and calling in photographers.

The campaign against injunctions became a personal mission for Ray Haynes, who replaced O’Neal as secretary-treasurer of the BC Federation of Labour in 1966. Son of a Vancouver cop, he first became a union man in the late 1940s while working on the green chain at the unionized Canadian White Pine sawmill. After drifting around a bit, he wound up in the wholesale division of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Unhappy with the low wages and poor working conditions, he helped organize a union there, eventually parlaying his abilities into a job with the Retail Wholesale and Department Store Union.

During his dozen years with the union as a robust organizer and international representative, Haynes excelled at the rough and tumble of organizing small bargaining units and getting them contracts against resistant employers. He came to realize the value of assistance from a centralized organization like the BC Federation of Labour in winning disputes without the resources and might of large industrial unions. The Fed’s only full-time leader for the next seven years, Haynes’s passionate push for labour unity and militancy helped propel the organization into becoming a major combatant in BC’s labour wars. A cartoonist’s delight with his black-framed glasses and prominent features, the pugnacious, poker-playing Haynes became one of the most recognizable individuals in the province, scourge of employers, governments and newspaper editorial writers.

Appointed to the position on his thirty-eighth birthday and already infuriated by the Lenkurt charges, Haynes soon had more cause to be upset. “I’d been on the job one day, and already ten more people were in jail for contempt of court,” he remembered. For two years, the International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union (ILWU) had tried unsuccessfully to get maritime employers to recognize statutory holidays included in a rejigged Canada Labour Code. In a bid to bring the issue to a head, the union advised members to ignore a call to work on Good Friday. They did. This sent the employers to court. There, they obtained an injunction prohibiting the union from calling for a similar work stoppage on the next holiday. Union officers paid no attention to the order, and on Victoria Day the waterfront fell silent once again. A few days later, Canadian area president Roy Smith and nine local presidents were cited for contempt of court.

In a ringing courtroom defence, Smith justified defiance of the court’s order. “We cannot and we will not allow ourselves to be bullied by the employers into doing something which will take away the rights of the membership,” he declared. Unmoved, the court fined Smith $500 and the others $400 each, with the option of three months in jail. All chose prison. “To pay our fines would be an encouragement to the employers’ tactics of seeking injunctions and fines as means of harassing our union and draining its financial resources,” the group said in a collective statement.

Off they went to the provincial prison camp in Chilliwack. The fact that ten men were in jail for trying to force companies to comply with the Canada Labour Code roused the dozing federal government to action. Labour minister Jack Nicholson promised to strengthen the code’s holiday provisions to ensure they applied to dock workers. The ILWU got the holidays. But the fact that employers were able to use the courts to undermine such a legitimate cause reinforced labour’s determination to erase injunctions from the field of struggle. “This one item has caused more bitterness and unrest than any other issue in this province,” said Haynes. “It has no place in twentieth-century industrial relations.”

On the other side of the judicial bar, the courts were also getting edgy, frustrated that their orders were being regularly defied by labour leaders willing to accept time in jail. Instead of concluding that something was inherently wrong with the system, judges opted for even stronger sentences. The first figure to be hit by this “tough on crime” approach was the forceful head of the United Fishermen and Allied Workers’ Union, Homer Stevens.

In 1967, the colourful Stevens was already something of a legend in BC for his committed representation of commercial fishermen and fish-plant workers. Of mixed Indigenous and immigrant ancestry, Stevens had been dominant within the UFAWU since his election as the union’s full-time secretary-treasurer in 1948 at the age of twenty-five. A big man, his slow, deliberate nature belied an iron determination and vast knowledge of all the many aspects of the complicated, multi-geared fishing industry. His hide and those of others in the union had been toughened over the years by fighting off concerted McCarthyist attacks on the union’s communist leadership.

Forced to operate as an independent union after being exiled from the house of labour for its political leanings, the UFAWU had thwarted attempts to break the union by both the thuggish SIU and federal combines investigators, who alleged that bargaining for fish prices was illegal price-fixing. Further complicating union efforts was the legal status of fishermen as independent businessmen rather than workers dependent on the fish companies. Thus excluded from provincial and federal labour codes, the UFAWU held no certifications on the water. Nor was there dues check-off. The union’s ability to negotiate with the hard-nosed fish companies depended solely on collective support from individual fishermen, who had to be signed up every year boat by boat.

Negotiating leverage was almost entirely dependent on gauging the size and timing of the peak salmon runs, the same high-stakes showdown that had pitted fishermen against companies since the turn of the century. It was not for the faint of heart. The union had its biggest breakthrough in 1959, shutting down all segments of the coastal salmon industry for the first time in a successful two-week strike that produced large gains.

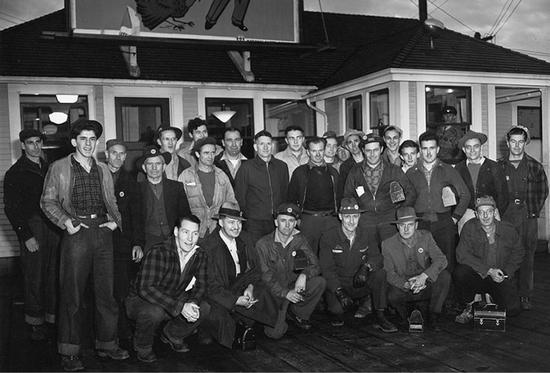

In 1967, however, the UFAWU launched a difficult strike to bring trawler vessel owners under a union crew-share agreement. With a strong mandate from crew members, the fleet tied up on March 25. A few days later, five trawlers came into Prince Rupert loaded with fish. When the UFAWU declared their catch “hot” and not to be processed, the owners swiftly obtained an ex parte injunction against the union. The UFAWU was directed to order its officers and members to allow the fish to be unloaded and processed. Instead, the union’s executive board put the issue to a vote by the membership, which voted 89 percent to leave the fish where they were. After going bad, the catch was dumped.

Notwithstanding the vote, some union shore workers at the large Prince Rupert Co-op fish plant began to handle fish caught by non-UFAWU boats. This brought union pickets and plenty of Mounties to the waterfront. At one point, Stevens, business agent Jack Nichol, twenty-one-year-old organizer George Hewison and fisherman Jose Verde were arrested by the RCMP, which had been running interference for non-union boats. The four were held in jail until midnight on charges that were never made public and never pursued. “You almost felt like you were catapulted back into the labour battles of the 1930s,” observed Stevens in his autobiography written with Rolf Knight. “It was about as stiff a battle as had ever hit the fishing industry in BC.”

Emotions intensified when the “Marching Mothers” began harassing the union. They were led by Iona Campagnolo, who went on to serve in Pierre Trudeau’s cabinet and later as lieutenant governor of BC. In those days she was a local school board trustee married to a fisherman and among a number of anti-union women who wanted the UFAWU gone from Prince Rupert. Contending the UFAWU had brought nothing but division to the community, the mothers paraded through the city with banners calling for its decertification at the Co-op and urging the union to get out of town.

The situation was further worsened by the role of the Deep Sea Fishermen’s Union, a Prince Rupert–based CLC affiliate that had been signing up boats behind the union’s back. A vote to decertify the UFAWU at the Co-op was the last nail in its coffin. In August, after signing several trawl agreements elsewhere on the coast, the UFAWU bitterly called off the strike. By then, the courts had ruled on the decision to submit its order to the membership at the outset of the strike. Noting that despite repeated jailing, unions were continuing to ignore court injunctions, Supreme Court Justice Thomas Dohm said it was time to send a sterner message.

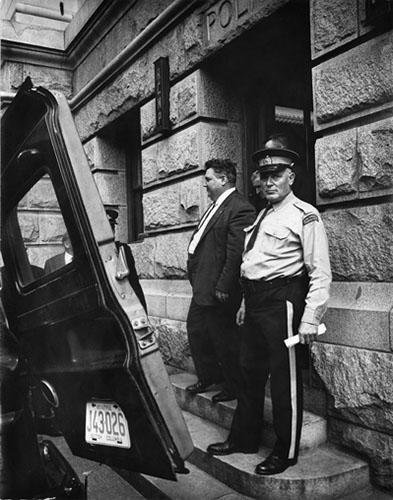

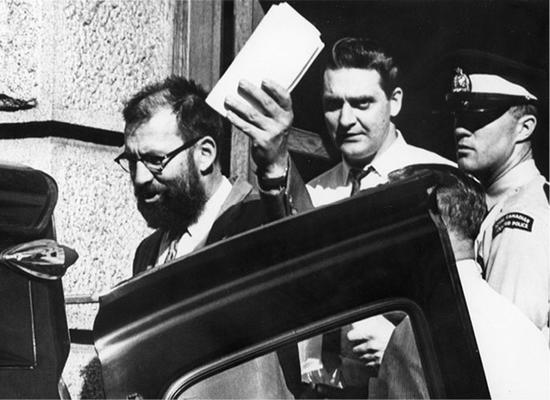

On June 21, in addition to fining the union $25,000, Justice Dohm sentenced Homer Stevens, union president Steve Stavenes and business agent Jack Nichol to a year in jail for contempt of court. “I am sorry for the families of these men,” he professed, “but they did what they did here coldly and calculatingly.” Justice Dohm warned that those disobeying future injunctions should expect even “more severe” penalties. With that, the trio was whisked from the courtroom to Oakalla, where they languished for ten days until lawyers managed to secure their release, pending an appeal.

Despite the UFAWU’s communist leanings and tendency to operate outside the mainstream union movement, the severity of the court’s punishment caused an uproar among organized labour. At the Vancouver and District Labour Council, there was talk of a forty-eight-hour general strike. “If this is equality under the law, we [might as well] move to some fascist country,” stormed VDLC president Paddy Neale, who had earned his spurs with his own six-month sentence. “The way injunctions are being issued, in a few years we could be getting thirty years. In ten years, we could be getting life.”

The call for a general strike did not get off the ground, but with seventeen trade unionists having been imprisoned in the last year, Ray Haynes announced a massive petition drive to end court injunctions in labour disputes once and for all. Tens of thousands of dollars were raised to help fight the case, including donations from some of the UFAWU’s fiercest anti-communist critics within the labour movement. When the BC Court of Appeal upheld the one-year jail terms meted out to Stevens and Stavenes (Nichol’s sentence was overturned by a 2–1 decision), the Fed announced a special convention on injunctions for January 1968. “Continually imprisoning trade unionists does nothing to improve the already chaotic labour-management relations in this province,” said Haynes.

At the anti-injunction convention in Victoria, Haynes hammered away at the devastating impact Bill 43 and the resulting accumulation of injunctions had had on unions. With the ban on leafleting, protesting outside an anti-union business, or publishing information about working conditions there, organizing had become an exceedingly uphill battle. Labour cited the legislation as a major reason unionization had fallen from its high of 53.9 percent in 1958 to 42.7 percent in 1966.

“You can picket any supermarket your heart desires providing you are protesting prices or the sale of Dow chemical products,” Haynes told delegates. “But Lord help you if you picket some anti-labour sweatshop employer to advise the public that he has no union agreement or that he has fired his employees because they tried to organize a union.” He referred to an ongoing strike at Canada Rice Mills in Vancouver. There had been no incidents, no violence, no mass protests, nothing but peaceful picketing. But that hadn’t stopped the companies from seeking seven separate injunctions in the previous six weeks. Although it would take five more years before anti-picketing injunctions ended, labour’s unrelenting campaign had made the matter a prime area for change.

The BC labour movement had also reached a realization that extraordinary measures were often needed if any disputes were to be won. Led by the Federation of Labour, unions demonstrated a significant uptake in collective solidarity and a willingness to wage industrial-relations warfare on a wide scale for the first time in years. The province had received its first inkling of this combative mood in late 1965, which hinged on the emergence of automation as a worrisome workplace issue. With more and more jobs being lost because of production advances, the labour movement opted to throw its weight behind a challenging strike on that very issue by the Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers Union (OCAW).

Faced with rapid automation that had cut its membership in half at the province’s seven unionized refineries, the OCAW sought protection and/or compensation for future employees sent packing by technology. At the bargaining table, union negotiators demanded eighteen months’ written notice of further automation, retraining for displaced workers and generous severance pay.

When the oil companies refused to even address the matter, the OCAW served strike notice at all refineries, electing to walk out first at the British American Oil refinery on September 14, 1965. Due to the very technological change the union was confronting, company supervisors were able to maintain regular deliveries and production at the plant. When talks continued to go nowhere, the union launched a second strike at Imperial Oil’s Ioco refinery on November 5, fuelled by the company’s suspension of thirty-five workers. A strike deadline at the other five refineries was set for midnight, November 15. That brought a pumped-up BC Federation of Labour into the action.

This time, there would be more than angry words and demonstrations. Labour leaders began planning the first general strike in BC for close to half a century. Determined to go to bat for the oil workers, who were finding it difficult to pressure the industry, the Fed aimed to shut down much of the province for forty-eight hours in conjunction with the OCAW’s own expanded walkouts. To give the Federation more time, the OCAW extended its strike deadline to midnight, November 24. Plans were worked out at a series of large meetings attended by union representatives from across BC.

A general strike would demonstrate “labour’s solidarity in support of oil workers battling for protection against automation,” the Fed’s strike co-ordinator George Johnston told the Vancouver and District Labour Council. “Perhaps we should have done this a long time ago.” The plan involved a forty-eight-hour “hot declaration” imposed on all petroleum products, which would essentially shut down unionized industrial workplaces throughout the province. Others untouched by the oil embargo would also walk out.

When the strategy was announced, industry and government seemed to break out in hives. Union leaders have “rocks in their head,” raged Socred Attorney General Robert Bonner. Labour minister Leslie Peterson called it an NDP plot. “It’s the most idiotic call I’ve ever heard of.” A front-page story in the Vancouver Sun explained helpfully to readers that a general strike is “the hydrogen bomb in organized labour’s arsenal… and the collective finger of the BC Federation of Labour is now on the button.”

Some international union representatives opposed the action. Dave Chapman of the International Association of Machinists advised his union’s six thousand BC members to stay on the job. “Like it or lump it, there are laws,” Chapman told the Vancouver Sun. William Ladyman, Canadian vice-president of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, instructed IBEW members to report for work. In defiance of his directive, and foreshadowing the Lenkurt dispute, they voted overwhelmingly to back the strike.

Amid feverish media coverage, the pressure began to build. With two days to go, the Canadian Manufacturers’ Association and its six hundred members in BC warned workers of “serious consequences” if they left their jobs, ranging from a loss of rights and benefits to suspension to outright dismissal. But the oil workers’ cause was bolstered from an unexpected source.

Ed Lawson, BC leader of the independent Teamsters Union and perpetual thorn in the side of the Federation of Labour, had refused to join the Fed’s general strike. To the surprise of his adversaries, however, he said Teamster truck drivers would refuse to “handle or use” any oil products considered “hot,” as soon as the oil workers expanded their strike. Once their gas tanks were empty, trucks would be off the road. “You don’t have to be a genius to figure out what effect that … will have on the trucking industry in the province,” said Lawson. It would be a strike in all but name.

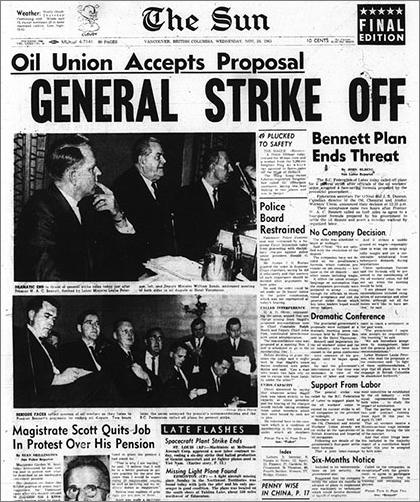

As the hours ticked down, the government grew alarmed at the prospect of mass job action. W.A.C. Bennett blinked. On Wednesday, November 24, with the strike due to begin at midnight, he called both sides to meet with him at the Hotel Vancouver. There, he tabled a proposed settlement and strongly advised the parties to accept it.

Bennett’s package included a joint labour-management committee to study the impact of automation. In the meantime, companies would have to provide six months’ notice of layoffs. For displaced workers, there would be retraining and one week’s pay for every year of service. The proposals were far beyond anything the industry had offered. The OCAW quickly agreed to the premier’s terms. Far from happy, the oil companies waited until a few hours before midnight before they reluctantly said yes too.

It was a significant victory for the union and organized labour in BC. Thanks to the oil workers’ breakthrough, automation was now on the bargaining table. Employers could no longer simply dismiss the adverse effects of technological change as the way of the world. Many other industrial unions began to negotiate agreements that also tempered technology’s impact on workers. Knowing the issue was won because of the collective solidarity and strength of virtually the entire labour movement made the result that much sweeter. The next day, a triumphant Federation of Labour took out a bold ad in the Vancouver Sun. Under the headline “THANK YOU!” in large black letters, the organization acknowledged all those who had pressured the government and big international oil companies into addressing automation, “the foremost of all challenges facing both blue- and white-collar workers.”

After years of noisy protests that yielded few concrete results, this was a high-water mark for the revitalized Federation. There was no turning back. Under Ray Haynes, the organization had worked hard to plaster over its cracks to become a unified, centralized force to be reckoned with.

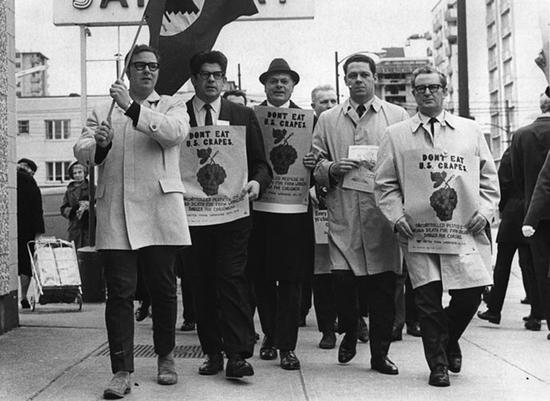

Stormier times were ahead for the Federation and the labour movement, but when he was not in the trenches, Haynes pushed the Fed to take stands on social issues that were not immediate concerns of its 125,000 members. The Federation gave unswerving support to a boycott of non-union-picked California grapes in aid of the courageous organizing crusade of Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers union. Chavez made regular appearances at Fed conventions to personally thank the BC labour movement, which he said was the most effective in North America.

In its annual brief to the Social Credit cabinet, the Federation took several positions on the environment, opposing oil drilling in Georgia Strait, flooding the Skagit Valley and logging at Cypress Bowl above West Vancouver. The brief harshly criticized the government’s inaction on pollution control while calling for grants to municipalities to fund anti-pollution campaigns. At the 1971 Fed convention, delegates urged affiliates to set up environment committees and negotiate anti-pollution funds into their contracts. An employer contribution of one cent for every hour worked by an employee could raise $3 million a year to help protect the environment, the Fed asserted.

Just before the convention, the Federation made an unprecedented gesture in the campaign for nuclear disarmament. On November 3, to protest a US underground nuclear test on Amchitka Island, Haynes called on union members to stop work for thirty minutes as part of a “Shutdown for Survival” labour protest against the explosion. Despite little notice, some did. A front-page picture in the Vancouver Sun showed a group of hard-hatted construction workers marching against the nuclear test, peace symbols on their placards.

“For the first time in North America,” Haynes told protesters outside the US consulate, “workers are downing tools, not over wages, not over working hours, and not over working conditions, but because of a danger to all mankind.” At Fraser Mills in New Westminster, local IWA president Gerry Stoney said three hundred workers stood in the canteen during the protest. “If we had a week’s notice, we could have almost shut down the industry tight,” said Stoney.

Vancouver Sun columnist Bob Hunter, the legendary co-founder of Greenpeace, heaped praise on Haynes and the labour movement for its stand. “Let me take my furry Yippie hat off to organized labour in BC,” he wrote the following day. “Never before had labour unions on this continent stopped work over an issue like this one. The stoppages may have been spotty, but some workers did it … More to the point, their leadership not only endorsed the move but pushed for it. That was a first.” The BC labour movement was also an active participant in the many protest marches against the US war in Vietnam, a marked contrast to the military cheerleading of AFL-CIO president George Meany and other American trade union leaders.

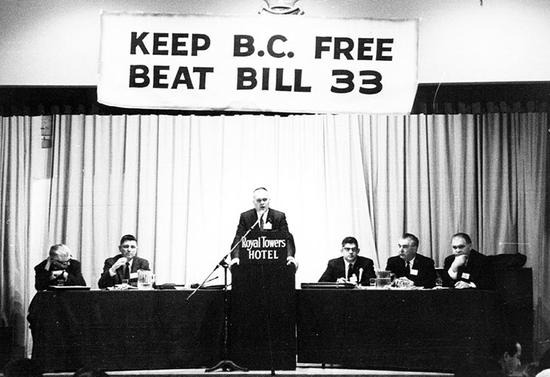

Haynes’s last four years with the Federation were dominated by the long, concerted fight against Social Credit’s most anti-union legislation yet. Spooked by growing labour unrest in the province and a strike by BC ferry workers, the government introduced the Mediation Commission Act (Bill 33) in early 1968. It provoked all-out war. For the first time in peacetime Canada, a government gave itself powers to settle disputes in both the public and private sector through binding arbitration, a capacity that existed nowhere else in North America.

Strikes and lockouts deemed by the cabinet to be against the public interest or public welfare were to be referred to a three-person Mediation Commission, which could then impose a settlement commissioners decided was “fair and reasonable.” Once a designated dispute was before the commission, job action was prohibited, with heavy fines for noncompliance. Bill 33 also banned provincial government employees from going on strike at all.

“Labour is going to put up a fight that’s never been put up before,” vowed Haynes. Two weeks later, the Federation held a special convention to map its plan of attack. This time, calls for a general strike were deflected. Instead the Federation opted for protracted battle. Union members were asked to donate a day’s pay to finance the fight. There were public protest meetings, pamphlets with the slogan “Keep freedom alive—beat Bill 33” and pledges of full support for any union forced into compulsory arbitration.

Bill 33 did not become law until December. By then, the Federation’s strategy was in hand. At its annual convention a few weeks earlier, more than six hundred delegates voted unanimously to boycott all hearings by the Mediation Commission. It was a strong policy, and undoubtedly one reason the government avoided an early showdown with the labour movement over the act’s draconian powers. When strikes occurred, government mediators continued to work with the parties without involvement from the Mediation Commission.

But labour’s boycott was not airtight, as evidenced by a serious spat between the Federation and the OCAW just a few years after organized labour had committed to a general strike to back the same oil workers in their struggle against automation. In May 1969, when the OCAW again struck the oil companies in a more normal dispute over wages, solidarity went out the window. Besides quarrels over the OCAW’s picketing and fundraising tactics and a “hot” boycott, there was disagreement over response to a tragedy on the picket line. Two months into the strike, oil worker James Harvey was struck and killed by an oil truck driven by a non-union employee as he walked an early-morning picket line at the Shellburn refinery. To commemorate Harvey, thousands of union construction workers booked off work for half a day. But the OCAW vetoed a Fed plan to shut Shellburn down completely with mass picket lines.

More aggravating was the OCAW’s decision to ignore labour’s boycott of the Mediation Commission. In a telegram, Haynes warned the union that “any co-operation [with the commission] can only be detrimental to the entire labour movement.” The OCAW went anyway, contending the process might lead to a voluntary settlement.

The lengthy strike was eventually settled without the Mediation Commission, but Haynes remained furious that a union that had benefited greatly from the Federation’s support in 1965 would so soon turn its back on a key policy. The Fed threatened the OCAW’s BC division with expulsion. In turn, the oil workers filed charges with the Canadian Labour Congress, accusing the Federation of “unwarranted interference” in the affairs of an affiliate. Before the feud could play out on the floor of the 1969 Fed convention that November, the two sides patched up their rift during a two-hour closed-door session on day one.

The peace accord wasn’t good enough for delegates increasingly rankled by Haynes’s tough, hands-on approach to affiliates. One of them was Vancouver labour leader Paddy Neale, whose jailing for defying an injunction in the Lenkurt dust-up was still fresh. Neale decided to run against Haynes, demanding the organization return to co-ordinating rather than dictating strategy for affiliates embroiled in difficult strikes. Haynes retorted that past conventions had endorsed a strong leadership role for the Federation and he saw no reason to change it. His view prevailed. In a significant vote that confirmed the Federation’s brawny activism under Haynes, delegates rejected Neale’s bid 299–178.

As labour strife swirled around them, the BC Government Employees’ Association gathered in the fall of 1968 for its annual convention. The BCGEA had recently wea-thered seven years of no dues check-off, after it was abruptly cancelled by W.A.C. Bennett in 1960 over the association’s membership in the BC Federation of Labour. “Our whole world seemed to be coming to an end,” said BCGEA president Ed O’Connor, looking back. “There’s no doubt that it was [Bennett’s] way of getting even for the strike in 1959.” In full panic mode, the provincial executive voted to suspend affiliation with the Fed in hopes the government would restore payroll dues deductions. There was no response.

The move forced the association to virtually beg employees for their $2 monthly payments. Membership and revenue fell by 40 percent. Thanks to the efforts of hundreds of volunteer collectors like Ike Nelson, however, the association managed to survive until late 1967, when Bennett just as unilaterally restored dues deductions. “We had about eighty members in the Williams Lake branch in those days,” remembered Nelson. “I was the guy who would give ’em the gears if they didn’t pay their dues. I had to go from unit to unit to pick up the money.”

At the 1968 convention the organization debated whether to call itself a union. “Let’s be honest. We’re working stiffs who aren’t earning the money we should be,” said liquor store delegate Bob McMaster. “We’ve got nowhere with the name ‘association.’ Adopting the name ‘union’ would make a big difference.” But delegates voted 51–48 to remain an “association,” still concerned the word “union” would frighten members away.

A heated convention fight over the issue repeated itself in 1969. Again the vote was close, but this time “union” advocates won a narrow victory. When the tally was announced, even those opposed to the change joined in rousing cheers that rocked the convention floor. There was no turning back. “If you walk like a duck and talk like a duck, call yourself a duck,” reasoned the organization’s bright new thirty-one-year-old general secretary, John Fryer.

The hiring of Fryer, with his degree from the London School of Economics and stints as research director for the CLC and the AFL-CIO, was a clear sign that BC’s government employees had embarked on their most determined course yet to win the same collective bargaining rights that their counterparts enjoyed across the country. With a new slogan, “Collective Bargaining Rights Now!” the BCGEU raised its monthly dues, hired a full-time communications director, took on more organizers and began to seriously pressure the government for real negotiations. The way had already been set by the provincial ferry workers’ pivotal twelve-day strike the previous year. That resulted in a signed deal, although the government insisted it was merely a “memorandum of agreement,” not a formal contract.

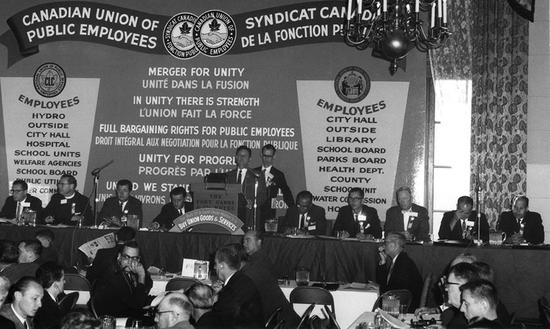

For other unions in the public sector, the 1960s was also a time of breakthroughs and expansion. The greatest leap forward took place among municipal workers. Two unions, the fifty-thousand-strong National Union of Public Employees (NUPE), which had a broader reach than civic employees, and the thirty-thousand-member National Union of Public Service Employees (NUPSE), whose roots went back to 1921, concluded seven years of difficult, sometimes testy negotiations with a new national union. The founding convention of the Canadian Union of Public Employees was held at Winnipeg’s Fort Garry Hotel on September 24, 1963. Overnight, CUPE became the second-largest union in the CLC, trailing only the United Steelworkers of America.

Most of BC’s sixty-nine delegates opposed the merger. They did not like paying extra dues when they felt well served already as members of NUPE. But opposition soon melted away and the new union rapidly began signing up unorganized public employees across the province. For CUPE’s three full-time regional reps in BC, it was a daunting chore to both service and organize over such immense distances. Interior rep Pete Driedger liked to say his territory covered “eight hundred miles, three mountain ranges and two time zones.” Initially, he operated out of his car, lugging around a

homemade plywood box full of files and a red portable typewriter, which he used to type up agreements in his hotel room. His life was not made any easier by independent-minded locals who had always done it their way and by directives from the national office with little understanding of BC geography. “They’d say things like, ‘While you’re in Prince George, why don’t you run over to Prince Rupert and see what’s going on there?’” Driedger recalled.

The hard-working union rep left a valued legacy when he negotiated a difficult master agreement for Kelowna municipal workers that contained a solid union security clause. Driedger used language in the Kelowna clause, based on a template devised by CUPE research director Gil Levine, as a negotiating benchmark for other agreements throughout his territory. For the next thirty years, Driedger’s contract was used by the union across Canada as a model of what can be achieved for workers at the bargaining table.

Within ten years, CUPE had more than doubled its membership, supplanting the Steelworkers as Canada’s largest trade union. The public sector’s rapid growth was beginning to change the nature of the trade union movement. It was not long before nearly half the members of the CLC worked for various levels of government. “Labour in Canada had always been a blue-collar, predominantly male organization,” observed labour historian Desmond Morton. “Public-sector unions added hundreds of thousands of members who were women or middle class, or both.”

As Morton noted, many of the new recruits were women. But it was telling that among BC delegates to CUPE’s founding convention, Verna King, secretary of NUPE’s Fraser Valley District Council, was the only woman. She went on to serve several years on the executive board of CUPE’s BC division, again as the lone woman. “The union sent me to talk to women in different locals to tell them how it would be good for them to be part of the unions. In those days, women didn’t always believe that,” King recounted. “Union work is very demanding. But I made a lot of friends through it. They are the finest quality of people you could find. You never forget them.”

For Thelma Roberts, secretary at Quamichan Junior High School in Duncan, unionization also meant walking a picket line for the first time when her CUPE local went on strike to win better wages for women workers like herself. “I didn’t even know how to walk a picket line,” she remembered. “I just knew you had to keep moving. Once, [CUPE rep Tom Smith] came up to me and said, ‘Thelma, you don’t have to walk so fast.’”

In 1966, CUPE beckoned the large Vancouver Civic Employees’ Union (VCEU) in from the cold. The union, representing outside workers at City Hall and the Pacific National Exhibition, had been tossed out of the mainstream labour movement during the purge of communist-led unions in the early 1950s. As an independent union that resisted numerous raids from other unions, the VCEU had staged several successful strikes, winning wage increases that raised the bar for all municipal workers. After fourteen years outside the house of labour, the union opted to join CUPE as Local 1004. At first, Cold War forces continued to keep the left-wing Vancouver local out of the Canadian Labour Congress. Only when CUPE threatened to withhold its large per-capita payments to the CLC did the congress relent.

Lengthy municipal and school board strikes became less of a rarity as CUPE members increasingly resisted employer attempts to lowball their wages in the face of escalating costs. “Our challenge is to stop governments from thinking of public employees as instruments of fiscal policy,” national president Stanley Little told CUPE’s annual convention in 1969. “It seems the lower down you are on the economic rung, the more you get stepped on.” There were long strikes in Kamloops, Penticton, Trail and once more in Vancouver. Through all the disputes, CUPE followed labour’s boycott of the Mediation Commission, sometimes under intense political fire. “We were called down to Victoria and pressured by the minister of labour. But we wouldn’t buckle,” said Alan Underwood from CUPE’s striking Trail local. Public-sector workers were making their mark in BC’s seasoned trade union movement.

The Hospital Employees’ Union (HEU), representing non-professional health-care workers, had emerged in 1944 when separate male and female unions at Vancouver General Hospital united to fight for better conditions for themselves and their patients. Bill Black, described in his obituary as “a fiery diminutive Scot,” became its early secretary-business agent and was respected enough to become the first elected president of the BC Federation of Labour in 1956. Adopting an industrial union model, the HEU was soon organizing across BC, growing in strength as public health care became the norm in Canada.

The HEU was one of the first locals to join the new Canadian Union of Public Employees in 1963. Five years later, the union won its first province-wide master agreement. The landmark pact standardized rates and working conditions in all of BC’s unionized hospitals, setting the tone for the union’s ambitious drive to organize long-term care facilities in the private sector.

Elsewhere in the public sector, with vast numbers of new teachers needed to handle baby boomers flooding the classrooms, the ranks of the BC Teachers’ Federation grew dramatically, launching the union on a tradition of militant leadership that made it a force to be reckoned with in education. Registered nurses, too, flexed their bargaining muscle, even under the staid labour-relations umbrella of the Registered Nurses Association of BC. Since receiving its first hospital certification in 1947, the RNABC had twice threatened to strike, in 1957 and 1959, when hospitals refused to accept a conciliation board’s contract recommendations. Each time, the government came up with extra money.

On the political front, after three election defeats in nearly thirteen years at the top, BC NDP leader Bob Strachan’s resignation in 1969 led to a testy battle between Tom Berger and Dave Barrett to replace him. At the leadership convention, union delegates were almost all for Berger. With their support, Berger eked out a slim thirty-six-vote victory. The capable, youthful labour lawyer was seen as “a man of the times,” compared to the province’s aging premier. NDP election billboards displayed a smartly dressed individual striding toward the legislature, attaché case in hand, with the words “Ready to Govern.”

All signs pointed to the end of Social Credit’s seventeen years in government. Instead, Bennett won his largest majority ever. Bennett’s over-the-top accusations that Berger’s NDP would put unions in control of the province worked. For added measure, Bennett unleashed the communist bogeyman, conjuring up visions of state-owned collective farms and comparing labour’s urging of members to vote NDP to the Soviet Union’s suppression of Czechoslovakia. Social Credit’s slogan, “Strike Pay with Berger. Take Home Pay with Bennett,” struck home. The NDP was reduced to a humiliating twelve seats. Given the extent of labour turmoil that swept over BC during the next few years, a more accurate election prediction would have read, “Strike Pay with Bennett.” The province became a forest of picket signs.

There was an indication of what was to come even as Bennett campaigned on keeping unions in their place. BC telephone workers were into the second month of their first strike in fifty years. It was a lively dispute. With supervisors able to maintain telephone service, the Federation of Telephone Workers went after repairs and installation work. Flying picket squads picketed construction sites whenever non-union installers showed up. Coupled with a BC Federation of Labour “hot” declaration against all new telephone wiring, the tactics put a serious crimp in construction activity throughout the Lower Mainland.

On the picket line, stoked by years of resentment against the company’s US-style industrial relations, the workers’ mood was buoyant. As pressure mounted on both sides, the federal government, which had jurisdiction over the communications industry, stepped in and a tentative two-year agreement was reached, nudging wages up by 2.84 percentage points over the company’s pre-strike position. It was not a large amount, but members voted 65 percent to accept. Getting the hard-boiled honchos at BC Tel to move at all was a victory, and a newfound solidarity had emerged among the union’s clerical, traffic and plant divisions.

Ever since Social Credit brought in the Mediation Commission, the number of strikes had been going up. The lid came off in 1970, a year that became an industrial relations battleground from beginning to end. Over the course of the year, a record 2.9 million workdays were lost through labour disputes. So much for “Take Home Pay with Bennett.”