5. The Great War and Canada’s First General Strike

The outbreak of the ghastly “war to end all wars” in 1914 had a profound impact on the BC labour movement, as it did on almost every aspect of provincial life. Among the fifty-five thousand British Columbians who went off to the butchery in Europe were many workers, motivated both by patriotism and a deep recession that made jobs hard to find. The war and a slumping economy cut BC union membership in half, from twenty-one thousand in 1913 to less than eleven thousand in 1915.

The longer the war went on, however, the more matters began to change. Labour shortages increased unions’ bargaining power, while paycheques eroded by wartime inflation whetted an appetite for fighting back. Workers not in the trenches flocked to join unions once again. By 1917, BC union membership was back over twenty-one thousand, a trend that continued until 1919, when an impressive forty thousand workers, representing 20.8 percent of the workforce, held union cards. At the same time, the terrible death toll in a conflict that seemed to have neither point nor end hardened class attitudes. What could be more unjust than an economic system allowing capitalists to profit from a war that was killing millions of workers?

Inspired by the 1917 Russian Revolution as well, many workers—particularly in the West—became increasingly militant and radical. The federal government’s promotion and eventual enactment of conscription was a tipping point. At the 1917 convention of the BC Federation of Labor, delegates elected a socialist slate bitterly opposed to conscription, a key rallying point in the growing class war. They were further infuriated by the Trades and Labor Congress of Canada, powered by eastern-based craft unions, which had swung behind mandatory military registration. “The Labor movement of the east is reactionary and servile to the core,” stormed The BC Federationist. A resolution to fight conscription with a general strike received overwhelming support from Vancouver trade unions. Although the conscription strike didn’t happen, workers were downing tools throughout BC, from the mines of the Crowsnest and Kootenays to the shipyards, laundries and shingle mills of Vancouver. All told, upwards of fourteen thousand BC trade unionists hit the bricks in 1917, followed by more than sixteen thousand in 1918. Such labour turmoil was unprecedented to that point in the province.

This simmering anti-capitalist anger erupted into out-and-out rage when charismatic union activist, socialist and organizer Albert “Ginger” Goodwin was fatally shot on July 27, 1918, by special constable Dan Campbell in the woods overlooking the working-class bastion of Cumberland. Goodwin, a vice-president of the BC Federation of Labor, had been hiding out to avoid a politically suspicious order that he report for military duty. The order, which followed his equally dubious reclassification from unfit to fit for service, took place during a strike he led for an eight-hour day by Trail smelter workers. The Dominion Police had been tracking him for months. Although the precise circumstances of Goodwin’s killing remain inconclusive, there is no doubt he died a martyr to the cause of working-class struggle, pursued solely for his trade union leadership.

Remembered for his role in the 1912–14 coal strike, Goodwin was revered by the people of Cumberland, who had helped him survive his clandestine existence. Already a veteran of nearly nine years in the mines of Yorkshire and Canada, Goodwin had come to Cumberland the year before the strike began, five months shy of his twenty-fourth birthday. His solid play for the local soccer team and growing espousal of socialism and worker rights soon made him a community fixture. On a hiring blacklist after the strike, Goodwin managed to find work at the smelter in Trail, where he significantly upped his activism. He ran for the Socialist Party in the 1916 BC election, winning 20 percent of the vote. He helped organize and was elected full-time secretary of the local smelter workers’ union. He was also chosen as a vice-president of the BC Federation of Labor. His prowess as a Socialist orator, urging “the wage slaves” to rise up and overthrow “the master class,” led to many speaking engagements. A reporter for the Vancouver Daily World covering a Goodwin speech at the Rex Theatre on August 19, 1917, praised his socialist knowledge and calm delivery. Six months later, he was on the run.

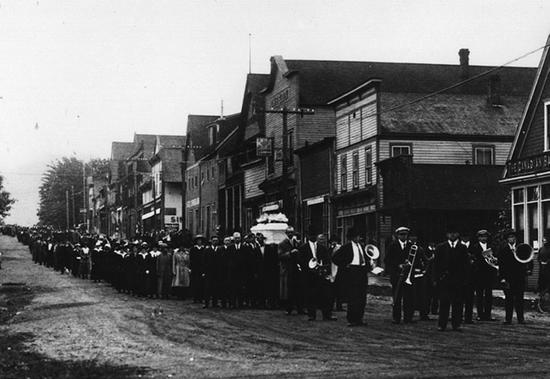

His sombre funeral procession, led by the municipal band, stretched from one end of town to the other. “The casket was packed shoulder-high right through Cumberland,” miner Ben Horbry recalled years later. “When one bunch of men got tired, another bunch took over.” Police were told to make themselves scarce. “The miners were so incensed over it,” Horbry said. “It was a good thing for [Dan] Campbell that he got out and disappeared when he did. He would have been hung or shot.”

In Vancouver, news of the shooting hit like a thunderbolt. At noon on August 2, the day of Goodwin’s funeral in Cumberland, close to six thousand workers walked off the job across the city to mourn Goodwin and protest his fatal shooting. Shipyards and the docks were shut tight. Trolleys were taken off the streets by their drivers. Construction trades, linemen, garment workers and other assorted groups also took part. The shutdown lasted twenty-four hours. It was Canada’s first general strike.

The business community reacted hysterically to the show of union force. Branding strike leaders as both pro-Bolshevik and pro-German, they incited hundreds of ex-soldiers into a frenzy. The vets, some fortified with booze, proceeded to ransack the Labor Temple at Dunsmuir and Homer Streets. They destroyed records, broke up furniture and assaulted several VTLC officers. Secretary Victor Midgley only just avoided being tossed from the building’s second floor when switchboard operator Frances Foxcroft bravely stood in front of the window to protect Midgley as he crouched on the outside ledge. The mob did not leave until the union men knelt and kissed the Union Jack.

The next day, with many workers still off the job, the same veterans tried to invade the Longshoremen’s Hall. This time, union members were ready, beating back all attempts by the soldiers to get inside. The strike was a resounding success, giving unions a strong taste of collective action.

The intensive class struggle and political action that permeated much of the first two decades of the twentieth century in British Columbia did not leave women sitting on the sidelines. Many had already shown their mettle during early strikes in the coalfields of Vancouver Island, hectoring strikebreakers and helping to hold their families together with little income. In Vancouver, which had emerged as an increasingly working-class community, women resisted the prevailing view they should remain at home with no part in industrial work. They joined existing male unions. In occupations where women dominated, they formed their own unions. As on Vancouver Island, they also backed the struggles of male workers while playing a major role in union label campaigns to push goods produced by union workers.

Toiling long hours in small, scattered work sites, with little access to child care or even public transportation, Vancouver women were far from a union organizer’s dream. Yet as labour historian Star Rosenthal points out, the fact that some organized at all “argues either a large degree of class-consciousness, or a large degree of desperation, or both.” Much of the activity was stoked by Helena Gutteridge, the city’s most prominent woman activist almost the moment she arrived from England in 1911. Relentless in her drive for women’s suffrage, she was also a social reformer and active trade unionist.

By 1914 Gutteridge was president of Local 178 of the Journeymen Tailors’ Union of America and the first woman elected to the executive of the Vancouver Trades and Labor Council. Later that year, as the city was swept by unemployment, she organized an exceptional co-operative to provide work for impoverished women struggling to make ends meet. The Carvell Hall Cooperative Settlement made toys, dolls and puddings, rushing them into production in time for Christmas sales. Scores of women found work at the “toy factory,” earning $3.50 a day, three days a week. Others did sewing work. At the end of the year, proceeds amounted to more than $2,500. Although hostility by business operators and some male workers eventually did in the co-operative, the tireless Gutteridge barely paused for breath.

Gutteridge was in the forefront of the successful 1916 referendum that at last gave British Columbia women the right to vote. (Asian and Indigenous men and women remained barred from voting.) During the campaign, prompted by fears that increasing numbers of women replacing men in wartime factories would become low-wage competition, the labour movement reversed its previous support for women’s suffrage. A wrong-headed editorial in The BC Federationist predicted that once women had the vote, they would help keep the establishment in power, while their presence in the workforce would enable employers to roll back fifty years of trade union gains.

Despite her anger at this turnabout, Gutteridge continued to work with the VTLC. In 1918 she and several other women led a spirited campaign supported by the labour movement that resulted in BC’s, and Canada’s, first minimum-wage law for women workers. Although the law fell short of guaranteeing a living wage, it did result in significant pay increases for women in many areas of employment. The measure had been piloted through the legislature by another female pioneer, Mary Ellen Smith. The widow of union leader-turned-politician Ralph Smith, she was BC’s first woman MLA, elected in a by-election as an independent Liberal with the slogan “Women and children first.”

Mary Ellen Smith subsequently became the first female cabinet minister and first female Speaker in the British Empire. A true social reformer, albeit with the era’s prevalent prejudice against Asian immigrants, Smith also spearheaded legislation establishing social welfare for abandoned wives, mothers’ pensions, workplace protection for women, female appointments to the judiciary, and juvenile courts. In 1929 she represented Canada at the International Labour Organization.

In September of 1918, Helena Gutteridge headed a gutsy strike by city laundry workers, almost all of whom were women. They walked out at seven laundries after managers threatened to fire them if they didn’t quit their union. The owners quickly agreed to boost their pitifully low wages, but refused their demand for a closed shop, requiring them to hire only union members. At a lively meeting punctuated by cheering and wild applause, the strikers voted unanimously to reject the owners’ offer.

With solid backing from other unions, the women redoubled their efforts. They built wooden picket shelters, organized whist and dance nights to raise money, and rallied awareness at public meetings, undeterred by the death of four of their members from the worldwide outbreak of Spanish flu. “The laundry workers have decided to fight to the last ditch,” wrote Gutteridge in The BC Federationist. Alas, after four months on the picket line, the laundry workers voted to return to work. As in so many strikes, management simply refused to budge on the matter of a closed shop. Eighty women and twenty men were not hired back. Still, their militancy yielded real gains for those who were rehired. The new Minimum Wage Board awarded the laundry workers higher wages than their original demand.

Less successful were attempts to form a waitresses’ union and the Home and Domestic Employees Union (HDEU) of British Columbia. But the latter union did raise awareness of the plight of domestic workers, forced to work up to fourteen-hour days for just $30 a month and room and board. With policies that were both radical and feminist for the time, the union was led by Lillian Coote. She rejected the idea that domestics were mere service workers, viewing them as industrial workers under the capitalist system. During its two years of existence, the HDEU operated from an office in the Labor Temple, campaigning for a nine-hour day, a minimum wage and a union hiring hall.

Women retail clerks, described by the Vancouver Trades and Labor Council as “among the most exploited classes of labor on earth, subjected to the whims and idiosyncrasies of both customers and petty bosses,” also drew union attention. The Retail Clerks International Protective Association (RCIPA) was one of the first labour organizations to welcome women into its ranks, going to bat for earlier closing times, higher pay and an end to wage discrimination. “Every trade unionist whose female dependents … work in stores should see that they are made acquainted with the aims and objectives of the Clerks’ Union,” said organizer W.H. Hoop.

Not strong enough to combat tight-fisted merchants head on, the RCIPA did have some success encouraging union members to shop at stores employing union clerks. One was the pioneer family shoe store Ingledew’s. An ad listing pro-union stores in The Federationist referenced Ingledew’s as “Two soles with but a single thought. The Union Man and The Ingledew Shoe.” The RCIPA also exposed some of the shortcomings of the new Minimum Wage Board for female workers. After an investigation, the board proclaimed a minimum wage of $12.75 a week for women clerks, a level decried as ludicrous by the union.

Helena Gutteridge, whose laundry workers had received a much more favourable ruling, produced evidence showing $16 a week was the bare minimum a female clerk needed to get by. But efforts to raise wages by organizing more women retail workers were hampered by store-owner intimidation. Five pro-union women were fired by Spencer’s Department Store in late 1917, and Woodward’s sent managers to spy on union meetings at the Labor Temple to make sure none of its employees were present. Three years later, the clerks’ union in Vancouver was mostly dormant, not to resurface until the tail end of the Depression, but the foundation had been laid.

In the midst of all these struggles, the workers of BC achieved a significant milestone. In 1917, after many promises and strong protestations by labour, the government passed a meaningful Workmen’s Compensation Act. Rather than forcing injured workers to fight for compensation against deep-pocketed employers in the courts, the act guaranteed them 55 percent of their average earnings, and monthly payments of $20 plus $5 per child to widows of employees killed on the job. The act allowed employers to escape being sued over workplace deaths and injuries, but workers welcomed the security of knowing they would be compensated. The new act was also the first in North America to provide comprehensive medical aid for injured workers. And it covered almost all workers, rather than restricting it to select occupations as did the trailblazing but imperfect 1902 compensation act. During its first year, the new Workmen’s Compensation Board (WCB) registered six thousand employers covering seventy-five thousand workers.