6. One Big Union

When World War I finally came to an end on November 11, 1918, the spirit of resistance was soaring in Western Canada, especially among industrial unions. Despite double-digit inflation eating into workers’ pay while unregulated profiteering thrived, government and owners continued to reject workers’ rights to negotiate better wages and working conditions. Anger was particularly acute in BC, which had the highest inflation and unemployment in Canada. A record number of strikes hit the province in 1919. Union membership was at an all-time high.

The first two years after the Great War were the high-water mark of radical trade unionism in Western Canada. The temper of the times was reflected during a labour hall meeting in Victoria. Hobbling to the front of the hall on his crutches, a veteran of World War I demanded that the Union Jack draping the speaker’s podium be replaced by the red flag. “The realization is growing that there is a class war, a war in which there is no discharge,” chimed in a supportive William Yates of the city’s Street and Electric Railway Employees.

Having lost vote after vote at the annual convention of the middle-of-the-road Trades and Labor Congress of Canada in 1918, the radicalized Western Canadian union leaders’ frustration could not be contained. The TLC leadership’s decision to support conscription was the last straw. They decided to forge their own path. Western union representatives met in Calgary in the spring of 1919 to map out industrial unionism in a big way, free from the dominant craft unions they derided as too rigid and conservative. This division between industrial workers and those in craft unions with specific skills was to plague the labour movement for years to come.

One-third of the 239 delegates had made the journey to Calgary from British Columbia. Most had attended the BC Federation of Labor’s convention purposely held in Calgary just the week before, where moderate views were brushed aside. The Federation also abandoned its long demand for Asian exclusion. “This body recognizes no aliens but the capitalist,” delegates declared. “Asian workers should be encouraged [to join] white unions, for it is a class problem, and not a race problem that confronts the white mill-worker in BC,” exclaimed The BC Federationist. Finally and most significantly, the Federation announced its intention to embrace a single workers’ organization to take on the forces of capitalism, once and for all.

Delegates at the socialist-dominated Western Labor Conference that followed saw no need to spend any more time lobbying politicians and trying to elect their own representatives. They embraced direct action and general strikes as the way to end political repression and win breakthrough measures such as a six-hour day. The conference called for workers to rally behind a new, militant and radical organization called simply One Big Union (OBU). Industrial workers across the West stampeded toward the OBU as their organization of choice. By the end of the year, nearly twenty thousand BC workers were paying two cents a month in dues to the OBU: teamsters, metal workers, construction workers, railway workers, shop craft workers, miners and, significantly, loggers.

Given the low pay, dangerous work and grim accommodation early loggers endured, the province’s largest industry had always seemed ripe for unionization. But isolation and the transient nature of logging were rough terrain for union organizers, regularly rousted out of the camps by obdurate operators. Loggers liked to say there were three crews in the camps: one coming, one going and one working. Although the IWW had managed some inroads, it was not until the emergence of the Lumber Workers Industrial Union (LWIU) in 1918 that a union was able to take on the forest companies. Within a year, enhanced class attitudes brought on by the war, continued inflation and the misery of camp life had prompted eleven thousand BC woodworkers to join the LWIU, an enthusiastic supporter of One Big Union and its preferred weapon to achieve progress: the general strike.

The same mood prompted a five-day general strike in February 1919 by sixty-five thousand Seattle workers. Three months later, Canadian working-class fervour exploded into the historic Winnipeg General Strike. For six weeks, thirty thousand public- and private-sector workers withdrew their labour in a united bid to force Winnipeg employers to recognize unions and the right to collective bargaining. The breadth of the walkout, its disciplined non-violent organization and the harsh measures unleashed by authorities to crush it aroused workers across the country. Solidarity walkouts took place in more than two dozen Canadian municipalities from Victoria to Amherst, Nova Scotia, where more than a thousand workers shut down the town for three weeks.

While the Winnipeg General Strike remains a pivotal, much-studied event in Canadian history, these dramatic “sympathy strikes” are relatively forgotten today. Although Victoria came late to the struggle, five thousand mostly industrial unionists left their jobs for four days to protest the arrest of the Winnipeg strike leaders. Workers in Prince Rupert also walked out, as did miners in the Kootenays. And in Vancouver, ten thousand union members were off the job for an entire month in a sustained general strike to back workers in Winnipeg. Even after the Winnipeg General Strike ended in late June, Vancouver workers stayed out for another week.

Labour historian Elaine Bernard suggests their walkout was arguably more radical than the Winnipeg General Strike: “While the Winnipeg strikers were supporting workers engaged in a struggle with the local captains of industry, the Vancouver strike was remarkable in that it was motivated by solidarity for workers more than a thousand miles away.” The strike in Vancouver had gradually expanded in response to the city’s threats to fire its own employees for walking out and to the city allowing private vehicles to carry paying passengers. By mid-June those off the job included stevedores, shipyard workers, streetcar drivers, telephone operators and linemen, CPR workers, woodworkers, teamsters, brewery workers and city employees including non-emergency police and firefighters. Vancouver strike leaders soon issued their own set of demands, including compensation and pensions for veterans and their dependents, nationalization of food storage plants to combat postwar hoarding, and a legislated six-hour day for all industries hit by unemployment.

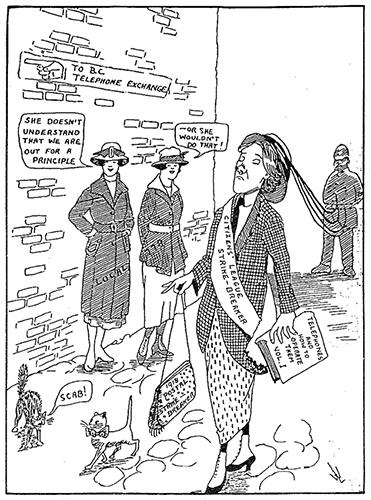

The city’s women telephone operators, regrouped as IBEW Local 77A, had been called off the job on June 14, 1919. After locking the doors and dropping keys through the window of BC Telephone’s Seymour Street headquarters, more than three hundred operators and supervisors joined the general strike. BC Telephone responded by recruiting seventy-six strikebreakers, many of them society women, to maintain service. As the strike continued, the financial pinch on the striking women was acute. “My landlady didn’t come looking for rent money. She kept me going,” operator Leona Copeland told The Federationist. “I was pretty close to brass tacks. Most of us who stayed out couldn’t afford to stay out, but we did.”

Not only did they stay out, but the Vancouver telephone operators were the last of the sympathy strikers across Canada to return to work. In an ultimately unsuccessful effort to prevent supervisors from being disciplined for joining the picket line, they remained off the job for another thirteen days after the general strike officially ended. Afterward, The Federationist doffed its hat to the operators’ resolve. “The action of the telephone girls in responding to the call for a general strike has placed them in a class by themselves amongst all women workers in this province,” lauded the labour paper. “These girls have won the admiration of all those who admire grit and working class solidarity.”

Another unusual feature of the Vancouver general strike was a censorship board set up by the International Typographical Union (ITU), whose members printed the city newspapers. Prevented from striking, the ITU set up a committee “to ensure the publication of the strikers’ views and [to prevent] deliberate misrepresentation … under penalty of cessation of work.” They made good on their vow by shutting down the Vancouver Sun for five days over its anti-strike diatribes. The Vancouver Province also lost an edition because of an anti-strike ad that ITU members refused to print.

With unions having no inkling that any of their demands would be met, coupled with growing threats of government-backed vigilante violence, momentum eventually faded. The Vancouver general strike officially came to an end on July 4. All told, forty-five union locals had taken part, a remarkable response considering that the original vote by union members in favour of the strike was hardly a landslide: 3,305–2,499. The strike committee ran up a grand total of $462 in expenses.

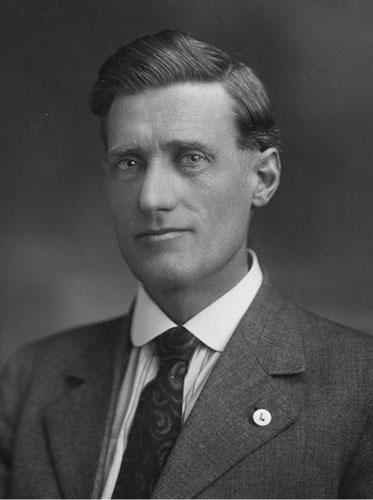

An ardent socialist and president of the Vancouver Trades and Labor Council, Ernest Winch had been in the forefront of the city’s general strikes in 1918 and 1919. He was also the energetic head of the expanding Lumber Workers Industrial Union. With LWIU offices springing up across BC, the province’s first “war in the woods” ensued. Over the next two years, government records list eighty-one separate walkouts by disgruntled lumber workers. Most resulted in substantial on-the-job improvements. The union was also One Big Union’s largest affiliate, constituting more than 40 percent of its total membership.

The popularity of the OBU’s revolutionary industrial unionism set off alarm bells in the ruling class. In Vancouver, police staged night-time raids on the homes of socialist labour leaders such as Winch, Bill Pritchard, Jack Kavanagh and Victor Midgley. Offices of The Federationist and other left-wing publications were ransacked and BC Federation of Labor records seized. Most companies refused to negotiate with OBU locals, while the national Trades and Labor Congress, egged on by international craft unions, cancelled the charters of unions and local labour councils that joined or supported the OBU. These counterattacks, along with the usual media and government hysteria over “Bolshevism,” were effective. At the same time, the BC Federation of Labor surrendered its charter voluntarily to the TLC in 1920, mistakenly thinking One Big Union was the future. And Vancouver’s grand Labor Temple, its financial resources crippled by the split, was bought by the province.

Nothing illustrated the hurdles faced by the OBU more vividly than what happened to the fighting coal miners of the Crowsnest Pass area in BC and Alberta. After voting more than 95 percent to leave the United Mine Workers (UMW) and join the OBU, six thousand miners went on strike in May of 1919, seeking higher wages, cost-of-living protection and better working conditions. But the UMW, which revoked the miners’ union charter, made a backroom deal with the companies, grouped together as the Western Coal Operators’ Association. There would be wage increases for the strikers, but only if they rejoined the UMW. At the same time, with the active support of the government-appointed director of coal operations, the companies imposed a UMW closed shop at all organized coal mines, meaning no one but UMW members could work there. One Big Union was blindsided, and the United Mine Workers regained control over a bitter membership.

There was also active opposition to the OBU by union moderates. In Vancouver, Helena Gutteridge and other leaders remained loyal to their international craft unions. They established their own labour council separate from the Vancouver Trades and Labor Council, which supported the OBU. As in the Crowsnest, employers united with international unions to freeze out the OBU. Its adherents were blacklisted, left to press demands that had no hope of succeeding. Inevitably, there were ideological divisions too, amid a worsening economy. After internal conflict over Ernest Winch’s plan to begin organizing workers in other occupations, the lumber workers dropped out of the OBU in 1920. They were not alone. Within a year the organization was a shell of its former self, reduced to running a lottery to stay afloat.

The revolution didn’t happen. Yet it would be wrong to see the rapid rise and fall of One Big Union as a historical blip. The attempt to build the OBU paved the way for the eventual rise of the US-based Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), which spearheaded an unprecedented union organizing drive across North America, including BC, from the late 1930s well into the 1940s. Labour historian David Frank observed that “the OBU was not so much an institution as an idea. It had an influence that went well beyond its high, short-lived membership.”

In contrast, the International Longshoremen’s Association had been a fixture representing Vancouver dock workers since 1912. Continuing the waterfront workers’ combative tradition that predated the turn of the century, the ILA was a strong union with solid membership support. It could point to real achievements: wages were now competitive with other West Coast ports and the union had established regular shifts. Dockside labourers no longer had to spend long, unpaid hours waiting in all kinds of weather for a ship to arrive and a chance call to work by a straw boss who regularly played favourites.

But in 1923, the Shipping Federation decided it was time to break the union. When the ILA advanced a series of modest demands for its next contract, the companies refused to negotiate. Not knowing this had been the Shipping Federation’s game plan all along, ILA members voted overwhelmingly to strike, setting up picket lines on October 8. The companies were ready. Protected by several hundred armed security guards who patrolled the waterfront day and night, hordes of strikebreakers were imported to load and unload the ships.

The strikers fought back. Teenager Albert Stock witnessed an onslaught on the strikebreakers at the Great Northern Railway Pier: “I heard all these longshoremen coming. They were pushing one of the tank cars from the Sugar Refinery. They pushed it right through the barricade, and it went to the end of the dock, just balancing over the end. The union guys were getting the men to leave. Every time one did, he got a big cheer.” Several union attackers were charged in the melee, which sent nine men to hospital. The ILA’s defence lawyer was none other than Gerry McGeer. A dozen years later as mayor of Vancouver, his union past forgotten, McGeer would unleash squads of mounted police against a march of unarmed union longshoremen.

The strikers held firm until December, but nothing, including pressure from a federal government conciliator and pared-down union demands, could move the companies. After nine weeks, members voted 584–337 to end their strike. The defeat was complete. The ILA disappeared from the waterfront. The Shipping Federation established its own hiring hall and a company union with a constitution that proclaimed, “Workers [must] support the existing form of government in Canada and resist all revolutionary movements.” A decade later, the Vancouver and District Waterfront Workers’ Association (VDWWA) developed into a strong union, shedding its company unionism and rising up to bite its employer overseers in the rear end.

After the strike, most ILA members were blacklisted. The Shipping Federation’s tough labour manager, Major William Claude David Crombie, could not resist rubbing it in when a striker asked for his old job back. “Well, young Will, do you know what the initials ILA stand for?” Crombie asked. “Yes, International Longshoremen’s Association,” the man replied. “You are wrong, Will,” gloated Crombie. “ILA stands for: I Lost All.”

Most of the Tsleil-Waututh and Squamish Nations’ lumber handlers from the North Shore, who had been reluctant supporters of the strike, survived the carnage. They regrouped the next year as the Independent Lumber Handlers’ Association (ILHA). Led by Andy Paull, the Bows and Arrows local was back. The ILHA had a three-storey union hall on the east side of Vancouver with a shop on the first floor, a bootleg joint called “Tween Deck” on the second floor and a dispatch centre on the top floor. Before merging with the VDWWA in 1933, the union negotiated several contracts that improved conditions for its members.

But the fact the powerful ILA could be swept away was a reminder of the precarious status unions had in the first decades of the twentieth century. “Organized labour is in a death [fight],” rued ILA business agent Bill Pritchard. The same anti-union backlash tore into the lumber workers’ union, as the big coastal logging operations set up their own hiring hall in Vancouver, carefully weeding out anyone identified as pro-union. The companies also began to realize that the better loggers were treated, the less likely they were to join a union. Camp food improved, as did health care, sanitation, bunkhouse conditions and grievance processes. A downturn in the forest industry, an ideological split and the union’s inability to organize sawmill workers also contributed to a fall in membership. A few years later the ambitious Lumber Workers Industrial Union had all but vanished.

For LWIU leader Ernest Winch, it became tough just to earn a living. He returned to the docks, only to be frozen out by employers after the ILA strike collapsed. With few jobs available elsewhere, his family was reduced to living over a shoe factory in a single room separated by blankets. Meals were often sheep heads or fish-head soup. According to his son Harold, who went on to head the BC Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) political party for fifteen years, a businessman once offered his father a job if he would renounce his socialist politics. Ernest refused.

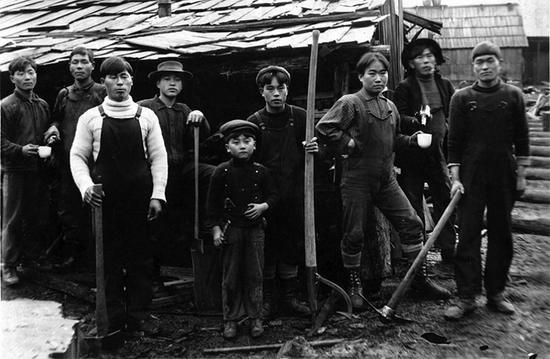

After the demise of the OBU, the newly reconstituted Vancouver Trades and Labor Council resumed its hostility to Asian immigration as a threat to non-Asian workers. This ignored the fact that Chinese lumber mill workers had taken part in the city’s two general strikes, while staging several walkouts of their own during the heyday of the OBU. With high unemployment and a recession in full swing, a VTLC committee proclaimed Asian immigrants “the most serious social menace facing the citizens of BC.”

The council, seven unions, five veterans’ groups and the Retail Merchants’ Association together reconstituted the notorious Asiatic Exclusion League. Among the league’s goals was educating “the white population to the terrible menace of Oriental immigration.” In 1923, supported by the BC labour movement, the federal government enacted the Chinese Exclusion Act, closing the door to any further immigration from China. The impact of the act was immediate. The “Oriental” share of the labour force fell from 20 percent in 1918 to just 12 percent by 1925. Over the next twenty-four years, until the act was repealed, no more than fifty Chinese emigrants managed to make their way to Canada. The province’s Chinatowns lost much of their vibrancy, dominated by aging, “single” males, many of whom continued to send money back to China for wives and children they were never to see again.

Matters were somewhat different for the Nikkei. Although immigration was restricted, it was not cut off completely. Hundreds of “picture brides” sent for from Japan helped ease the loneliness of the predominantly male immigrants and enhanced domestic life. But racism remained. Like the Chinese, Nikkei workers continued to be paid significantly less than non-Asians for similar work, and the Nikkei share of Fraser River fishing licences began to decline. With limited English, many immigrants were exploited by both white owners who padded their profits by paying poor wages and predatory Nikkei labour contractors, who got them jobs in return for a cut of the action. This double victimization was rarely understood by white workers. As they showed in the fishing industry, however, Nikkei immigrants were not always willing to turn the other cheek.

They were encouraged by the resourceful Suzuki Etsu, an acclaimed activist, journalist and translator who arrived in Vancouver from Japan in 1918. Suzuki soon began writing a column for the local Tairiku Nippo (Continental Times) that regularly called for common cause with non-Asian workers. During a 1920 strike at the Swanson Bay sawmill not far from today’s Hartley Bay south of Prince Rupert, Chinese and Nikkei workers joined other strikers to protest arbitrary wage cuts. About thirty Nikkei workers left on the next steamship to Vancouver. Although company pressure on the remaining workers led to the strike’s collapse, Suzuki sensed an opportunity. He organized a meeting of the Swanson Bay strikers at the Japanese Language School, where they were applauded by the Nikkei consul among others for uniting with white workers.

Out of that meeting came the Japanese Workers’ Union with Suzuki as its chief adviser. Not surprisingly, the Vancouver Trades and Labor Council refused the JWU’s request to affiliate. Yet the new union quickly made its presence felt, supporting a strike by Nikkei employees at the Alberta Lumber Co. sawmill in Vancouver. There, the racial tables were turned. White war veterans were hired as strikebreakers and the conflict was lost.

Suzuki continued to advocate for Nikkei workers. The Labour Weekly, a new paper he edited, targeted unscrupulous labour contractors. After the paper accused several Nikkei companies of making excess profits from supplying cheap food to camp workers, the publisher succumbed to strong pressure from wealthy Japantown merchants to shut it down. (During the Swanson Bay strike, a Japantown department store had sponsored newspaper ads for strikebreakers.) The dedicated Suzuki then began his own paper. Although boycotted by advertisers and forced to operate on almost nothing, The Daily People had many readers in the province’s isolated mills and lumber camps.

With more than a thousand members, the renamed Japanese Camp and Mill Workers’ Union was finally accepted by the Trades and Labor Council as its first Asian labour organization. Although Suzuki is not much remembered today, even by the Nikkei, historian Michiko Ayukawa concludes that Suzuki and his followers “had a tremendously positive impact on the community.”

Punctuated by the rapid rise and fall of the OBU, the 1920s were a challenging time for BC unions and those who believed in social change. Anti-union governments and hard-nosed employers were in the ascendancy. Union membership dipped dramatically while socialist/worker political candidates fared poorly. To put the cap on a difficult decade, Indigenous workers suffered another tragic loss. Not content with curtailing their hunting, fishing, logging and other traditional rights, authorities moved in on trapping. Northern First Nations had operated traplines since the beginning of the fur trade. Now, there were new registration requirements. Indigenous people would show up on traplines their ancestors had worked for generations and find non-Aboriginals there. George Archie of the Secwepemc lost a line he had trapped for twenty-five years. “The white people are taking Indian traplines, and the Indians cannot trap,” he wrote Indian Affairs inspector W.E. Ditchburn in 1927. “I would like you to help me get back my trapline, so I can support my family.” His plaintive plea fell on deaf ears.