7. The On-to-Ottawa Trek

No era in Canadian history is as well-defined as the Depression. Even the dates are precise, from the spectacular Wall Street crash on October 29, 1929, to the beginning of World War II on September 3, 1939. The bottom fell out of the economy, inflicting untold misery and poverty on millions of Canadians—whether ill-fated Saskatchewan farmers, eastern factory workers or labourers in BC’s once humming woods and mines. By the time it ran its course, the Depression had shown once and for all the inadequacy of an unregulated free market and the need for government action to ensure a decent life for ordinary people.

The ten lost years were characterized by government indifference. There was nothing like the New Deal of US president Franklin Delano Roosevelt that did so much to limit the plight of millions of hard-hit Americans. Instead, those unable to find work in Canada were provided with extremely meagre relief payments if they had a family—or if single, forced into work camps for a pittance. Both R.B. Bennett and William Lyon Mackenzie King, the country’s two prime ministers during the 1930s, were more concerned with balancing the budget than helping citizens in desperate need. Those who protested were more often than not clubbed or thrown into jail. “The image of a policeman’s truncheon bringing a shabbily dressed man to his knees was to become familiar,” wrote Pierre Berton in his angry book The Great Depression.

The Depression seemed to come out of nowhere. As the Roaring Twenties neared their end, prosperity continued its multi-year roll. Investors were making fabulous riches on paper from the ever-rising stock market, financing their wealth by loans and buying on margin. Production was at record highs. But consumers couldn’t buy everything. Worrisome stockpiles of unsold products began to accumulate. Then in the fall of 1929, the stock market’s Black Thursday, October 24, was followed by the even more catastrophic Black Tuesday of October 29, and the house of cards collapsed. Billions of dollars were lost in a single day. The Great Depression was on, triggered at its most basic level by overproduction, under-consumption and a sea of credit based on expectations of endless growth.

Products moving through BC’s formerly busy ports declined nearly 60 percent. Lumber production, critical to the province’s economic health, fell 30 percent. A scourge of horrendous poverty and unemployment fell over the land, never seen before or since. By 1933 one-third of all eligible wage earners, 1.5 million Canadians, were without work, many with no social safety net. For hundreds of thousands of mostly young Canadians, riding the rails, occupying jungle camps, visiting soup kitchens and bumming a meal became part of the rhythm of daily life. Large numbers of Prairie families driven from their land by dust storms, drought and plagues of grasshoppers added to the desperation.

Before long, with its relatively mild climate, Vancouver became the unemployment capital of Canada. In the fall of 1931, Andrew Roddan, minister of the First United Church, told a visiting federal cabinet minister that his church’s bread lines were feeding more than 1,200 people a day. Hundreds were sleeping in shacks made of bits of tin and wood, while others slept outside, often in the rain, among rats “as big as kittens,” Reverend Roddan reported. When a local restaurant began handing out bags of bread crusts at the end of the day, a hundred men would show up every evening for the scraps.

As most labour unions focused on their own members, and politicians with no answers tried to pass responsibility to other levels of government, the country’s Communist Party (CP) came to the fore. From its founding at a 1921 clandestine meeting in an Ontario barn, where the twenty or so delegates slept in the hayloft, the party had grown in influence during the 1920s. Although ever subject to the policy whims of the Moscow-based Communist International (Comintern), the CP had developed a base of skilled, committed organizers, who found the country’s hard-pressed industrial workforce and hordes of single unemployed men tailor-made for action. Ordered by the Comintern to abandon its previous policy of working within established unions, the CP established its own radical federation in early 1930, just as the Depression hit. The Workers’ Unity League (WUL) was to hold its red banner high for the next five years and play a major role in confronting authorities and the forces of capitalism.

A union of the unemployed affiliated with the WUL was soon leading regular protests and hunger marches demanding, with some initial success, better relief. Still, assistance remained barely above subsistence levels and predominantly restricted to families. For the masses of unemployed single men, many of whom washed up on the West Coast, there was nothing but charity. The WUL’s involvement in organizing the unemployed made authorities nervous. “Communist agitators,” they feared, were stirring up revolution among the throngs of jobless hanging around Vancouver and other cities.

To get them off the streets and away from the clutches of the Workers’ Unity League, the federal government devised a network of relief camps, perhaps the most mean-spirited of all the country’s responses to the ravages of the Depression. Most were wilderness work sites far from the city, where single unemployed men received bare-bones accommodation, skimpy food and paltry compensation in return for their labour. The first camps provided $1.15 a day. The men worked building roads, parks and other public facilities. A year later, pay was down to $7.50 a month. A year after that, all relief camps were taken over by the Department of National Defence. The daily stipend was further reduced to the derisory sum of twenty cents, and the trouble began.

Rather than squelching unrest, the camps proved fertile ground for communist organizers. While few camp workers had any interest in Stalin, they appreciated efforts to improve their lot and fight back against the camps’ harsh military-like rule. The Relief Camp Workers’ Union, a direct charter of the Workers’ Unity League, became a force in all eighty-three BC camps. Braving blacklists, camp residents staged numerous strikes and protests to demand better conditions, keeping abreast of activities in other locations through the union’s popular, surreptitious newsletter, the Relief Camp Worker. Much of the successful organization could be attributed to the efforts of one driven individual: Arthur H. “Slim” Evans.

In short order, Evans would become a household name across Canada and a red flag to governments, police and the courts wherever he led a fight on behalf of workers or the unemployed. Fiercely committed to working-class struggle, the lean carpenter in his mid-forties had already been wounded once and jailed three times for his role in union battles, including most recently in Princeton. There, a miners’ strike provoked cross burnings and frightening threats by a local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan, violent attacks on peaceful pickets, a late-night vigilante attack on a local union leader and the kidnapping of Evans himself. Yet it was Evans who went to prison, serving more than a year in jail on a charge of advocating the overthrow of the Canadian government during the strike. When he rejoined the relief camp protests in late 1934 as district organizer of the Workers’ Unity League, protests began in earnest.

Responding to growing strife in the camps, Evans and the Relief Camp Workers Union declared a strike on April 4, 1935. Their rallying cry, “Work and Wages,” was to resound for the rest of the Depression. Nearly fifteen hundred camp workers answered the summons to Vancouver, pouring into the city by rail, road and foot. The presence of so many young, restive unemployed men with no money and nothing to do, under the leadership of communists, unnerved civic leaders. Flamboyant mayor Gerry McGeer bombarded Ottawa with demands that they be rounded up and sent back to the camps.

But organizers displayed an astounding ability to feed and billet the strikers, keep them occupied and, most importantly, maintain order and discipline. In defiance of civic ordinances, they raised funds with regular tag days. Men wearing sashes that read “When Do We Eat?” worked four-hour shifts at busy street corners, holding out tin cans for donations. A sympathetic public showered them with cash. On one bumper Saturday, tin-canners brought in a record-breaking $5,500. With a sense of mischief, Evans, who had been up for forty-eight hours organizing the all-out blitz, asked police to safeguard the tidy sum until the banks opened Monday morning. When two officers arrived to carry off the money, he told them it was “Moscow Gold.”

Little was left to chance. The men were organized into four divisions, each with its own leader. There were committees for just about everything. All reported to the central strike committee headed by Evans. “We couldn’t slice a loaf of bread into five bologna sandwiches without appointing a committee to see it was done according to plan,” division leader Steve Brodie joked later. Hunger marches, demonstrations, tin-canning, large public rallies and boisterous snake dances through downtown streets became as familiar to Vancouverites as the North Shore mountains. May Day produced the largest parade in the city’s history.

Mother’s Day was even better. The Mothers’ Council, a broadly based, left-wing women’s group that was formed to muster sympathy for “our boys,” led a large Mother’s Day march to Stanley Park. There, they formed a giant heart around the young relief camp workers. That night, mothers across the city invited strikers to their homes for a meal. It was, said one event planner, “something of real value instead of the usual bourgeois, maudlin sentimentalism associated with Mother’s Day.”

The only trouble occurred during an impromptu snake dance through the aisles of the Hudson’s Bay Company on April 23. When police arrived to evict the protesters, a large glass display case was shattered and merchandise strewn about. Hundreds then marched down Georgia Street to the Victory Square cenotaph, where squads of RCMP, provincial police and city police surrounded them in a tense stand-off. A delegation of strikers was dispatched to the mayor’s office to try to defuse the situation. The twelve-member delegation got nowhere with the bullheaded Gerry McGeer. As they left his office, all but one was arrested for vagrancy. McGeer proceeded to a corner of Victory Square for a much-ridiculed reading of the Riot Act.

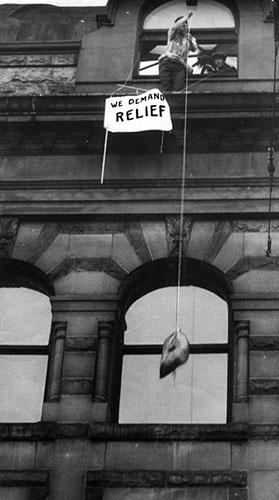

Six weeks into the strike, however, despite waves of public sympathy, there was no sign of either the city or Ottawa granting relief, providing “work and wages” or forcing them back to the camps. Running low on food, the stalemated strikers needed something different. On May 18, their four divisions marched off in different directions. Two headed to local department stores, one went to the West Vancouver ferry depot, while the fourth followed a familiar route toward Main and Hastings. But this time, catching police off guard, they strolled into the city library on the corner, headed up the spiral staircase of what is today the Carnegie Centre and began occupying the civic museum on the third floor. Barricading the door, they posted a large sign on the window: “When Do We Eat?”

Large, supportive crowds gathered in the streets below. Well-prepared, the men lowered baskets on a string. Citizens filled them with bread, pies and pastries from neighbourhood bakeries, jugs of coffee, cigarettes, chocolate and sweets. The bounty proved too much for some, who hadn’t eaten well in days. Bottles of pills were sent up to ease their stomach discontent. As police fumed, jubilant snake dances took over Hastings Street, accompanied by lusty renditions of the strike’s rallying song, “Hold the Fort.” (“Hold the fort/ For we are coming,/ Union men be strong./ Side by side keep pressing onward,/ Victory will come.”) For the first and only time in the protracted protest, Gerry McGeer gave in. By phone from the Vancouver Yacht Club, he agreed to have the city feed and lodge the fifteen hundred strikers over the weekend. The occupiers emerged from the library in triumph.

The tactic was typical of Slim Evans. He had a genius for maintaining momentum. “You can’t go on marching and singing and begging with tin cans,” he would say. “You’ve got to do something new.” Two weeks later, as the passage of time began to thin ranks, sap morale and cut into public support, Evans hit the strategic mother lode. At a mass meeting called to discuss the future of the faltering strike, someone put forward the idea of taking the protest to Ottawa. Evans seized on the idea. When the proposal was endorsed, the strikers nearly took the roof off the joint with their roars of approval. It was as if a huge jolt of electricity had revitalized their flagging spirits. They had a mission once again.

The ensuing On-to-Ottawa Trek remains one of the defining events of the Depression in Canada. It caught the fancy of the country in a way that not even Slim Evans could have foreseen. The journey came to epitomize everything that was wrong with the federal government’s hard approach to those brought low by forces beyond their control. The public saw it that way too. The farther the young BC trekkers travelled on top of swaying boxcars—many attaching themselves with belts or ropes—in their quest for a fair deal, the more they were embraced by Canadians as doing the right thing.

The idea was mad to begin with, of course. With a mere four days to prepare, little money and scant arrangements along the way, more than a thousand men had to be supplied and kept together for a three-thousand-mile journey to the lair of Prime Minister R.B. Bennett. Certain that it would quickly fall apart, governments and police could barely stifle a yawn when the trek was announced. But the relief camp strikers were charged with excitement by the sheer audacity of the plan. “Suddenly there was a new level of struggle. It was as if everything we had done up to that point was preparing for [this],” said trekker Willis Shaparla. Half a century later, Shaparla, a veteran of the D-Day landing, considered his participation in the On-to-Ottawa Trek the highlight of his life.

Yet no one knew what lay ahead the night of June 3, 1935, as hundreds of men clambered atop a line of CPR freight cars by the Vancouver waterfront and headed off into the darkness. Crowds had gathered to see them off. More than 800 left on the first train, another 200 boarded a later Canadian National Railway freight, and 350 more moved out the next evening.

The trek had a rough beginning. In Kamloops, the strikers’ first stop, civic officials were unfriendly, and many men grumbled over the poor arrangements. At the small mountain community of Golden, however, things turned around. Sooty, begrimed, exhausted and hungry after a chilly night ride through the Selkirk Mountains and smoke-filled Connaught Tunnel, men staggered down from their perches and marched toward a local auto park. “I was so cold, I could have fallen off the roof of the box car,” remembered Red Walsh. As dawn broke, there waiting for them was a bathtub suspended over a fire and a grey-haired woman stirring its contents—a vast beef stew—with a three-foot-long ladle. Other stew-filled washtubs were nearby. “Good morning, boys,” she hailed them. It was a stew the men never forgot. Long tables laden with bread and eggs added to their wonderful breakfast.

On they went to Calgary, passing a handful of relieved provincial police at the BC–Alberta border, who gave them a cheery wave. The swirling, acrid smoke that filled the many Rocky Mountain tunnels blackened faces, stung the eyes and made breathing difficult. But Calgarians cheered from their housetops as the sooty trekkers marched to the city’s exhibition grounds. Thumbing their nose at the city’s refusal to grant them a permit, they raised $1,300 in a tag day. And when authorities denied them temporary assistance, they occupied the provincial relief office until the government gave in.

New recruits arrived on boxcars from Edmonton. One of them was Phil Klein, father of future Alberta premier Ralph Klein. (During a fiftieth-anniversary re-creation of the trek, Ralph Klein, who was mayor at the time, welcomed surviving trekkers to Calgary and formally guaranteed them safe passage through the city. He then invited them to lunch.) Fulminations by politicians that the men were being led by communists cut less and less ice. “To be quite frank, we don’t care very much,” said an editorial in the Calgary Albertan. The public saw the protest as just, and the protesters as disciplined young men who wanted a better deal, not revolution. Before leaving Calgary, they were feted at picnics and flooded with food and clothing. Hundreds gathered to say goodbye.

Back in Ottawa, Bennett was stunned by the trek’s growing popularity. Over five hundred more men had joined the venture since Vancouver. Bennett determined that it must be stopped. He chose Regina. As communities continued to bend over backward to feed and lodge the eighteen hundred men on their overnight stops, the RCMP began drawing up a battle plan. Having learned of Bennett’s plans, the trekkers held a mass meeting attended by three thousand people in Moose Jaw. The mood was defiant. “If they attack us, we are not going to lay down and take it,” warned twenty-four-year-old Matt Young. That determination quickened their departure to Regina on the next evening freight.

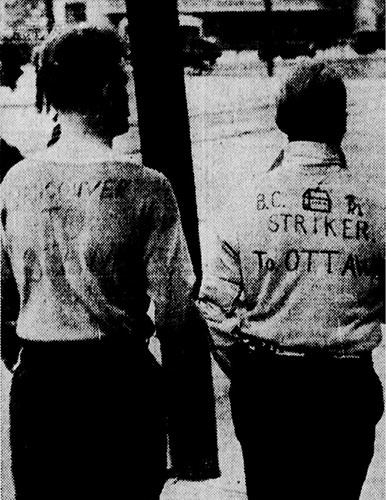

The overnight journey was terrible. A violent prairie storm replete with thunder and lightning lashed the men all night. But the strikers maintained their discipline. Arriving just after dawn on June 14, they made their way down from the boxcars, lined up in their divisions and proceeded in good order, four abreast, to the local exhibition grounds. Later that morning, they put on a show for the welcoming citizens of Regina, parading in a long line down Eleventh Avenue. “On to Ottawa” was chalked on the back of many flimsy jackets, and the men chanted, “Where are we going? Ottawa! Who’s going to stop us? Nobody!”

The RCMP had other ideas. Despite opposition from Premier Jimmy Gardiner and strong backing for the trekkers from the citizens of Regina, the Mounties moved hundreds of reinforcements into the city with the intent of stopping the boxcar cavalcade and arresting the leaders. Bennett leaned on the railways to no longer accommodate the trekkers. They were trespassing on private property, he reminded them. Nevertheless, Evans set June 17 for their departure to Winnipeg, where hundreds more single unemployed men were waiting eagerly to join up.

But Bennett put the trek on hold with a cagey invitation to the leadership committee to meet with him in Ottawa; in the meantime, the government promised the trekkers a week’s worth of meal tickets. Although Bennett’s invitation was clearly a delaying tactic to help the RCMP prepare, Evans felt they had no option but to accept. The meeting was a stage director’s dream. Dressed in their worn, rumpled clothes of the road, Evans and his committee sat opposite the corpulent R.B. Bennett, wearing a swallow-tailed coat and winged collar, with a diamond stick pin in his tie. It quickly degenerated into a bout of schoolyard name-calling. Bennett began by charging that the trekkers’ goal was not work but the overthrow of the government. If he believed that, Evans retorted, Bennett wasn’t fit to be leader “of a Hottentot village.” Furious, the prime minister shot back that Evans was an embezzler of union funds. Evans snapped that Bennett was a liar. “You are not intimidating me one bit.” The meeting came to a quick close. The verbal donnybrook between the two men was headline news across the country, setting the scene for the tragedy that followed.

By the time Evans and the delegation returned to Regina on June 26, the city was full of police with riot sticks. Their ranks included seventy-five Mounties freshly arrived from taking part in a bloody crackdown against striking dock workers in Vancouver. The trekkers were trapped, followed by police wherever they went. Assistant RCMP Commissioner Stuart Wood warned that any citizen assisting the trekkers would be subject to arrest. Donations dried up. Access to the radio airwaves ended. When only a sparse crowd turned out for a Saturday picnic on June 29, Evans realized there was no way forward.

He began to negotiate a resolution with Premier Gardiner, who was furious with Bennett and the RCMP for proceeding with no regard for the wishes of the province. The men were prepared to call off the trek and return west, Evans said, but they would not go to an alternate work camp in Saskatchewan as Bennett insisted. There matters stood on the Dominion Day holiday, July 1. In the circumstances, no one thought much about a rally scheduled that night for the city’s vast Market Square. The resulting Regina Riot remains one of Canada’s most widely known civil disturbances.

At 8:17 p.m., as a modest crowd of fifteen hundred listened to the rally’s first speaker, two loud blasts from a police whistle split the early evening air. Within seconds, police were charging through the terrified crowd, clearing a path to the speakers’ platform by knocking over anyone in their way with truncheons. Willis Shaparla called the sudden whistle and police charge “the most fearful moment of my life.” As people desperately took flight to escape the riot sticks, Evans and co-leader George Black were quickly collared and taken to jail. After a brief lull, the fracas turned into a riot.

The unprovoked attack on a peaceful gathering released an outpouring of bottled-up rage from the trekkers and equally angered citizens. Rocks, bricks and other projectiles rained down on police. A few attacked isolated officers with clubs and other weapons. Plainclothes city detective Charles Millar was struck and killed, his assailants never identified. The battle continued in Regina’s darkened downtown streets. Police advanced with tear gas, billy clubs, gunfire and fierce charges on horseback. Nick Schaack, an unemployed farmhand, received several blows to the head. He died in hospital three months later. Despite their numbers and firepower advantage, police did not manage to secure an edgy calm until 11 p.m. The city’s two hospitals treated more than a hundred victims, including some police and at least a dozen patients with gunshot wounds.

The next morning, outraged by the RCMP onslaught, Premier Gardiner wrested control of the situation from police and the federal government by arranging the strikers’ orderly departure. After their frustrating three-week stay in Regina, trekkers began to register for the trip home. All told, 1,358 men accepted the offer to leave—this time inside the trains and “on the cushions.” Two-thirds were from British Columbia, half from Vancouver. Although falling twenty-six hundred kilometres short of its goal, the On-to-Ottawa Trek, hatched in Vancouver, is remembered today as one of the country’s most inspiring protests. Sixty-six years later, at the age of ninety-two, trekker Harry Linsley told an interviewer, “All we ever wanted was work and wages.”

Two years after the trek ended, a number of participants were fighting in Canada’s Mackenzie–Papineau Battalion as part of the international contingent of volunteers against Franco’s fascist forces in the Spanish Civil War. Two who died, Peter Neilson and Paddy O’Neil, had been members of the trekkers’ delegation that met with R.B. Bennett in Ottawa.