9. Blubber Bay, Bloody Sunday

Labour history is often a tale of the unpredictable. Certainly, no one could have foretold that a former whaling station on Texada Island with the unglamorous name of Blubber Bay would be the site of the first critical strike by a newly formed organization that for decades would be the province’s largest and most important union. The eleven-month strike in 1938–39 by the International Woodworkers of America resonates still, with its combination of workers fighting hard for their union—and company and police actions that were shocking even for those repressive times.

The roots of the bitter confrontation go back to 1935. Even beyond its many strikes and protests, the year saw two key decisions that made it one of the most pivotal years in the history of the Canadian labour movement. Despite their profound implications for Canada, both decisions took place outside the country’s borders—in Washington, DC, and far-off Moscow. Meeting in the Soviet capital, the Seventh World Congress of the Communist International ordered communist-led unions in Canada to abandon their outsider status and throw their red caps in with the mainstream labour movement. It was time, the Comintern proclaimed, for a common front against fascism. That meant the abrupt dissolution of the Workers’ Unity League, which had spent five gainful years organizing and fighting for the unemployed and the country’s industrial workers. The WUL’s radical unions were now ordered to fold themselves into craft unions headquartered in the United States. At the same time, escalating tension between industrial unions and the craft union leadership of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) blew wide open into a complete rupture. The split was inevitable once the mercurial, charismatic leader of the United Mine Workers of America, John L. Lewis, punched out “Big Bill” Hutcheson, the pro-Republican head of the Carpenters Union, at the AFL’s stormy 1935 convention that summer in Atlantic City. Lewis and other industrial union leaders had made a pitch at the convention for the AFL to help them organize millions of employees in the nation’s mass-production industries. But the craft union members, proud of their status as skilled tradesmen, wanted no part of worker groups that one AFL leader derided as “riffraff [and] good-for-nothings.” After he and his industrial allies lost every vote, Lewis’s frustration boiled over into fisticuffs.

That November in Washington, Lewis presided over a historic gathering of fed-up industrial union leaders to form a new organization within the AFL, which became the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). Quickly turfed from the AFL and galvanized by the Roosevelt administration’s far-reaching Wagner Act that enshrined union rights, the CIO began organizing millions of workers into powerful, industrial unions throughout the United States. Without a northern equivalent to the Wagner Act, the CIO took longer to have a similar impact in Canada. But eventually, the robust CIO changed the face of labour here too.

Under pressure from the AFL, the Trades and Labor Congress of Canada expelled its industrial union affiliates in 1939. Ousted industrial unions soon merged with the relatively small All-Canadian Congress of Labour to form a more powerful Canadian Congress of Labour (CCL). Although minus much of the animosity that characterized the AFL and CIO feud in the United States, the TLC and CCL also operated as two separate, rival labour organizations. When the BC Federation of Labour re-emerged in 1944 (with a “u” in labour), it was for CCL affiliates only. And in Vancouver, each body had its own labour council.

The disappearance of the Workers’ Unity League, coupled with the rise of the CIO’s American-based unions, meant that for the next fifty years almost all private-sector unions in Canada had their headquarters in the United States. Although the pros and cons of this became a subject of heated debate in the years ahead, it was hardly an issue at the time. Only the CIO had the resources and the charisma to bring unionization on a massive scale to Canada.

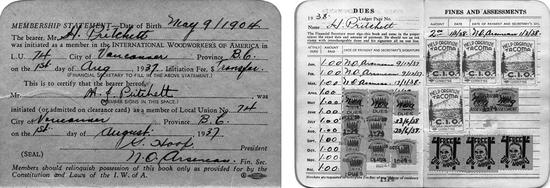

In BC, the Lumber Workers Industrial Union was first to be affected by these dramatic developments. The battle-scarred WUL affiliate obediently enlisted in the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners. It was not a good fit. Snubbed and forced to sit as second-class, non-voting delegates at the Carpenters’ annual convention, union lumber workers from Oregon, Washington and BC did not take long to map a different course. On July 17, 1937, at Tacoma, Washington, after receiving overwhelming support for the move in a union-wide referendum, heady delegates voted to join the CIO as the brand-new International Woodworkers of America. Harold Pritchett, the thirty-three-year-old committed trade unionist and communist who had led the Fraser Mills strike six years earlier, was elected president, the first and for many years the only Canadian to head a major international union.

In the United States, the move sparked an immediate organizing battle, laced with violence, between the Carpenters and the IWA. There, with companies compelled by the Wagner Act to recognize unions chosen by local bargaining units, the IWA managed to secure a majority of American lumber workers. But with no Wagner Act in British Columbia, it was tough sledding.

Along with other governments across Canada, the province aligned with powerful business interests and police to clamp down on union organizing at every turn. While thousands joined the IWA in Oregon and Washington, encouraged by US labour legislation, BC’s twenty-five thousand woodworkers remained virtually unorganized, stymied by persistent company refusals to recognize any union or bargain collectively. And why not? There was no legal compulsion to do either. When a union did strike for recognition, police were regularly dispatched to protect strikebreakers and break up union protests, while company blacklists ensured that pro-union loggers found it difficult to obtain work. In this imposing environment, successful strikes were few and far between.

Finally, in 1937, with a stated goal of furthering labour harmony in BC, the Liberal government of Thomas Dufferin “Duff” Pattullo passed the Industrial Conciliation and Arbitration Act (ICA). The legislation mandated conciliation, then arbitration, to settle labour disputes. It also recognized a few union rights. But tellingly, it put company unions and ad-hoc employee groups on the same legal footing as legitimate unions. Employers remained free to ignore unions chosen by the workers, a situation unchanged since the first organizing efforts of Nanaimo-area coal miners in the early 1870s. Still, as part of its recent embrace of reform over revolution, the BC IWA decided to give the ICA a chance at Blubber Bay.

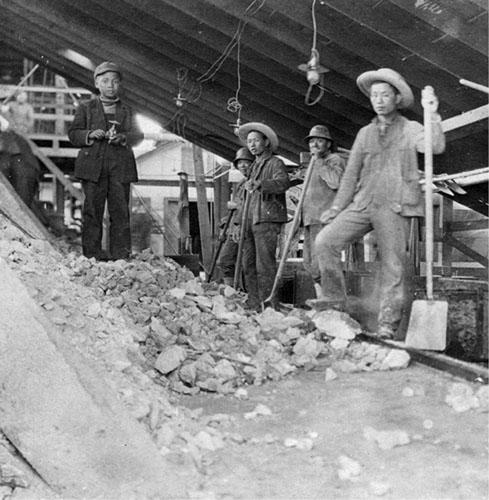

The one-time landing spot for removing blubber from captured whales on the northern end of Texada Island was now the site of a small sawmill and an enormous open-pit limestone mine. For thirty years workers, many of them Chinese, had quarried the 250-foot-deep “glory hole” with little labour turmoil, despite wretched working conditions. But an obstinate new manager and a wage cut spurred the workers to join the IWA. A six-week strike brought a modest wage adjustment and promises by the Pacific Lime Company not to single out union activists. Instead, once production resumed, PacLime fired local president Jack Hole and twenty-two other pro-union workers.

Rather than strike again, the IWA opted for the ICA. After lengthy hearings, the arbitration board appointed under the act recommended reinstatement of those fired. But the board refused to recognize the IWA as the workers’ union, allowing PacLime to brush off the recommendation. The ICA had proven useless. On June 2, 1938, after an angry public meeting, two-thirds of the company’s 156 employees walked off the job. For the union’s credibility, this was a fight the IWA had to win.

It turned into a strike like no other, where authorities acted as a law unto themselves, reminiscent of the Deep South. Along with the usual trappings of a company store and company housing, PacLime owned virtually all property and every facility in the community. During the strike, schoolchildren had to obtain a pass to cross company roads merely to attend school. Strikers were denied access to telephone and telegraph services. When union leaders were able to find a phone, police monitored their calls. Strikers were followed and often thrashed by company thugs if they wandered too far astray. High barbed-wire fences surrounded PacLime production sites. The officer in charge of the squads of provincial police sent in to protect strikebreakers helped recruit the scabs from provincial relief rolls.

Chinese strikers were ordered out of their bunkhouses. When union lawyer John Stanton entered the bunkhouses to retrieve some of their belongings, he was arrested. Other workers were evicted from their small family homes. On an island under police and company rule, union members had to find a way to survive. One of the few private property owners allowed members to set up camp on his meadow just outside town. Donated provisions, including tons of vegetables, had to be brought in from Vancouver. The Chinese strikers were particularly resourceful. By travelling in groups and letting it be known they were not afraid of a fight, they were left alone by company vigilantes. They slept in shifts in tents, deftly scrounging Texada for food.

In the unfortunate vernacular of the day, the IWA’s John McCuish saluted their resolve: “There was a lot of Chinamen. They went out on the docks and rocks, and caught rock cod. They killed deer. There were quite a few pheasants on the island, and they lived mostly on that … Them Chinamen were solid. I never seen such a bunch as solid as they were.” The IWA took pains to ensure Chinese strikers attended and voted at union meetings. “There can be no differentiation between a worker, whether he be white, yellow or black,” a union rep told the ICA hearings. Union demands included a base rate of forty-five cents an hour for all employees.

Success depended on stopping the flow of strikebreakers. Whenever Union Steamship delivered a group of new workers, confrontations erupted on Blubber Bay’s government wharf as police physically prevented strikers from stopping them. At times emotions boiled over. The worst incident took place in mid-September, three and a half months into the strike. As the steamer Chelohsin lowered its gangplank, local vice-president Bob Gardner yelled, “Here come the scabs among us!”

Strikers rushed forward, trying to get at them through heavy police lines. Clubs and tear gas drove them back. Police continued the chase along local roads, while strikers and company employees hurled rocks at one another. Eleven wound up in hospital in Powell River. Twenty-three strikers were arrested. That night, Bob Gardner, one of those arrested, was taken into a private room and beaten by Constable Andrew Williamson, suffering four broken ribs.

The next day, forty members of the Pulp and Sulphite Workers journeyed over from Powell River to warn police commander T.D. Sutherland that if police didn’t cool it, four hundred of them would be back “and we won’t fool with you bastards.” The day after that, sixty striking seine-boat skippers dropped anchor at Blubber Bay on their way to Vancouver. They left in the morning, buoying the strikers with a chorus of defiant horn blasts.

Despite the strikers’ resolve, the arrests from the dockside fracas did them in. Not only did they lose their leadership, defending those charged sapped the union of funds and energy. Charged with rioting and unlawful assembly, strikers were tried in groups of four, giving proceedings an aura of show trials. Twelve were convicted, sentenced to four to six months of hard labour at Oakalla prison. In a rare turnabout of justice, Constable Williamson also got six months at Oakalla for his brutal assault of Gardner.

With local leaders in jail, its coffers drained and PacLime operating normally, the IWA decided further resistance was futile. After eleven months, picket lines came down and the IWA virtually disappeared. While organizing drives thrived in the United States, BC remained a burial ground for industrial union aspirations. It took the coming war for seventy years of government anti-unionism to loosen and finally provide a fairer playing field for workers to organize. Bob Gardner would not be around to celebrate. Sentenced to four months in Oakalla, the forty-four-year-old former train engineer, still ailing from his injuries, contracted influenza while in prison and died.

As the worst of decades neared its end, it seemed as if the forces of law and order had become hooked on bashing anyone who rose up to demand change. For those who were not British subjects of the Commonwealth, there were arbitrary deportations with no right to appeal, regardless of their roots in the province. In Princeton, Vancouver, Anyox, Corbin, Blubber Bay and even in Regina, the recipe was the same: British Columbians who challenged the existing order were to be trampled. In Vancouver, this shameful period concluded with yet another calculated, cold-blooded attack on peaceful protesters. It remains known today as Bloody Sunday.

After the decisive ousting of Prime Minister R.B. Bennett, the economy took a marginal upturn. Premier Duff Pattullo, elected on his own “work and wages” program, unrolled a public works program that included the Fraser River bridge that bears his name. But toward the end of 1937, when the economy slowed once more, governments showed they had learned nothing from the turbulence of previous years. As before, no one wanted to pay for the rising numbers of unemployed. Ottawa cut grants to the provinces, including its 50 percent share of funding BC’s relatively successful forestry camps.

Unwilling to absorb the added financial burden, BC closed the camps down in the spring of 1938, driving six thousand unemployed men to Vancouver with little means of support. Organized tin-canning and communist leadership of the unemployed were back. Once again, the men were organized into divisions, causing familiar headaches for authorities with their constant marching. This time there was no Slim Evans to lead them; he was busy organizing. The man in charge was Steve Brodie, a few years shy of thirty but a veteran of the On-to-Ottawa Trek.

Brodie had lived the hard times of the Depression. Blown from his job on a farm by Prairie dust storms, Brodie rode the rails and suffered the indignities of the relief camps. After the trek came to its violent end in Regina, he drifted from job to job. His experiences had turned him into a communist. But Brodie preferred action over ideology. He felt tin-canning had run its course. “It no longer had nuisance value, nor could it provide enough for two fifteen-cent meals per man,” he recalled. Brodie opted for a bold strategy to bring the desperation of the unemployed right into government front yards. On the afternoon of May 20, he sent all four unemployed divisions on various downtown marches, spreading word that they were headed to Stanley Park.

Only division leaders knew the real plan. Brodie had meticulously timed and measured their routes to the last centimetre. At 2 p.m., seven hundred men marched through the doors of the imposing granite post office at Granville and Hastings Streets and sat down. Fifteen minutes later, as police hurried to the post office, three hundred men moved into the unguarded lobby of the Hotel Georgia at the corner of Howe Street. Another two hundred men strode farther west along Georgia Street to set up camp beneath the paintings of the Vancouver Art Gallery, then four blocks from its current site across from the Hotel Georgia. The fourth division simply paraded through downtown streets in a successful ploy to baffle police. The hat trick of occupations targeting federal, city and private-sector locations fired up the public’s imagination. Occupants were inundated with sandwiches, tinned goods, money and endless cups of coffee from nearby cafés.

Brodie shrewdly challenged police: if the occupiers are breaking the law, arrest them. It was his hope that mass arrests would finally force governments to accept responsibility for the long-suffering unemployed. But the mayor, the premier and the prime minister all stuck to their well-worn insistence that the unemployed were not their responsibility. Prime Minister Mackenzie King, who professed pride in his grandfather William Lyon Mackenzie for taking up arms in 1837 to fight for responsible government, denounced the protesters as “a bad lot. They do not want to work. They want trouble.” Authorities, however, blanched at the prospect of more than a thousand men clogging the city’s jails. They waited for the occupations to wither away. It was not to be.

Early on at the Hotel Georgia, nervous management agreed to pay the men $500 if they left. They took the money and left. But sit-ins at the other two locations stayed solid. Wickets remained open for business at the post office. Although art gallery officials opted to close their doors, there was not a hint of damage to any of the displayed artwork. A month in, the unemployed occupants had provided no reason to be evicted other than their cheek at being there. Finally, however, authorities ordered in the police, hitching their excuse to a health officer’s warning that disease might break out in the cramped, crowded quarters. MLA Harold Winch persuaded the men at the art gallery to leave if city police let them go free, which they did. There was no such resolution at the post office.

In the pre-dawn haze of Sunday morning, June 19, police massed menacingly on adjacent street corners. At 5 a.m., RCMP Colonel Cecil Henry Hill entered the building and ordered the men out. Brodie calmly replied that the protesters remained willing to be arrested, if they had broken the law. Hill’s cold response sealed their fate: “I have no orders about arrests.” Moments later, volleys of tear gas were fired into the midst of the protesters, and the onslaught began. Frantic, the men broke every window they could to bring in fresh air and rushed for the doors, blinded and choking from the gas. Gauntlets of police waited for them. As they emerged, a terrifying cascade of whips and riot sticks came crashing down on their heads. Brodie, easily visible in his bright orange sweater, was among the last to leave. Police singled him out for special attention. Blow after blow rained down on the defenceless protest leader. A chilling newspaper photo showed Brodie surrounded by police, his hands over his head in a futile effort to protect himself. He woke up at St. Paul’s Hospital twenty-four hours later, one of his eyes permanently damaged.

Thirty-seven other post office occupants were also hospitalized. Scores more were treated at the Ukrainian Labor Temple, its front yard covered with bloodied and bandaged victims. Livid by what had happened, those who had escaped injury and angry citizens raged along Hastings Street, shattering windows as they went. A spontaneous rally at Oppenheimer Park drew ten thousand people. Hundreds then massed outside the nearby police station, demanding the release of those arrested. Winch intervened again as a peacemaker. Climbing onto a light standard, the CCF MLA calmed the crowd, urging them to take their protest to Premier Pattullo in Victoria.

A one-hundred-strong delegation left on the midnight ferry, cheered on by large crowds of supporters. In Victoria, the answer was the same cold-hearted “no” that echoed just about every other government response to pleas from men at the end of their economic rope. “There comes a time when too much sympathy can be shown the men,” said the unfeeling Pattullo. Not long afterward, many of these men enlisted to fight for the same country that had shunned them when they needed help.

After nearly ten years of economic adversity, the dark days of the Depression showed few signs of brightening. In the early summer of 1939, unemployment remained stubbornly high, production levels in BC were still 12 percent below those of a decade earlier, and governments continued to resist spending money on social assistance. A million Canadians were on some form of pitifully low relief. Many others scrabbled to survive on nothing. Thronged by thousands of homeless, unemployed men, Vancouver had taken on the look of a shabby, beaten city.

Although the bleak situation drove many British Columbians to the political left, there was no significant breakthrough by the trade union movement. Without legislation compelling companies to recognize unions, overcoming determined anti-union employers—who had the help of police and governments—was simply too difficult. Workers were left with little love for the system that had done them wrong. “There were people who became leaders of the labour movement, who grew out of those days, and stuck with it all their lives,” said Syd Thompson, who himself became a long-time leader of the IWA’s Vancouver local and the city’s labour council. He was permanently scarred by his grim experiences during the Depression. “I have a hatred for this system that, in some ways, has never left me,” Thompson told an interviewer in 1978. “How could it be otherwise, I guess, after nine years on the bum?”