Chapter 1: The Lay of the Land

Immense, slow, and complex forces have shaped the land around Tofino and Clayoquot Sound. The scenery that has drawn millions of visitors to the west coast took its present form over eons of time and through cataclysmic geological events. The relentless actions of plate tectonics, volcanoes, earthquakes, glaciers, rivers, wind, and ocean waves have produced this landscape, leaving the entire west coast of Vancouver Island with a beautiful, bewildering array of geologic and geographic features.

The formation of the land around Tofino and Clayoquot Sound began in the tropical regions of the South Pacific some 200 million years ago, when the landmass that would become British Columbia did not even exist. Then, as now, massive tectonic plates that make up the earth’s crust and range in depth from thirty to one hundred kilometres moved very slowly on top of the earth’s molten mantle. The constant movement of these plates, resembling huge industrial conveyor belts driven by convection currents in the mantle, caused earthquakes to occur, volcanoes to erupt, mountains to form and portions of the earth’s crust to appear and disappear. What is now the West Coast of Canada lay east of today’s Rocky Mountains, with Pacific Ocean waves sweeping ashore where the foothills of Alberta now meet the prairies. These ancient Pacific waves crashed against the western edge of a large tectonic plate called Laurentia, which comprised the Canadian Shield and most of what would later become Canada. After moving slowly eastward for millennia, for some unknown reason Laurentia quietly changed direction and began moving westward at a rate of two to ten centimetres a year, bumping into offshore island chains and reef-like landmasses called terranes lying in its path. This slow collision caused the soft sea bed between the colliding landmasses to buckle and fold upward, forming the Rocky Mountains. This young fold mountain range, as geologists call it, thrust upward in exactly the same way as the Himalayas, the Alps, and the Andes, which explains why climbers and geologists find marine fossils in the layers of sedimentary rock as they ascend these ranges. This also explains why limestone—formed from coral and other living sea creatures—is still being mined on the western side of the Rockies.

Laurentia’s slow movement continued crumpling the sea bed for the succeeding 200 million years, incorporating other terranes into Canada’s western landmass. Sometimes this tectonic movement caused new volcanic activity to occur as plates forced their way over other plates along North America’s West Coast. Consider the string of volcanoes between Alaska and California: California’s Mount Shasta; Washington’s Mount Rainier, Mount St. Helens and Mount Baker; British Columbia’s Whistler Mountain and Mount Edziza; and Mount McKinley in Alaska—all the result of volcanic action brought about by plate tectonic movement.

A mere hundred million years ago, after five separate terranes slowly collided with the west coast of Laurentia to form most of British Columbia, the Wrangellia terrane showed up. Having begun its millennia-long journey somewhere in the eastern South Pacific near the island of Tonga, Wrangellia arrived off Laurentia, and slowly the two welded together. Wrangellia came equipped with ready-made volcanic mountains, which today make up the Vancouver Island Ranges, Haida Gwaii, and parts of southeastern Alaska. Formed of igneous rocks produced by volcanic activity, these Wrangellian mountains differ entirely from the sedimentary formations of the Rocky Mountains.

In geological terms, the West Coast’s Wrangellian mountains make the Rockies look like infants. Some of the rock in Wrangellia’s mountains dates back as far as 400 million years before Wrangellia hit the BC coast. This means that 200 million years before Laurentia collided with its very first terrane to begin to form the Rockies, the earliest signs of Wrangellia began emerging above the ancient South Pacific ocean floor near Tonga. Volcanoes erupted under the sea, pouring lava and ash upward to form islands. After the volcanoes stopped erupting and the lava cooled, coral and other tropical sea life began living on the cooled rock along the shorelines, forming coral reefs. River-borne sediments from these newly formed islands began washing down rivers to form deltas and broad coastal plains. Then, about 160 million years ago, volcanic action restarted the island-building process. Unlike the first undersea volcanic activity, this time the volcanic material, or lava, cooled in the air, forming rock that looked entirely different from that formed under water. When Wrangellia crossed the equator into more temperate climates, advancing at a speed of seven or eight centimetres a year, deposits of land-formed rock like shale and sandstone began to adhere to the moving platform of islands, increasing its size. This massive rock mass evolved as it moved; a lot can happen in a million years of travel.

By the time Wrangellia arrived off the coast of Canada, it had incorporated many newer forms of rock on its surface, but it still consisted largely of ancient igneous rock formed under the sea. Some of this 270-million-year-old rock, the oldest on Vancouver Island, can be found near Buttle Lake, about fifty kilometres east of Clayoquot Sound. A rock sample found at Grice Bay near Tofino is believed to be 260 million years old, and the bedrock of Lemmens Inlet also derives from the Wrangellia terrane. Lone Cone and Catface Mountain arrived in Clayoquot Sound on the Wrangellia terrane; their age, some 41 million years. Contrary to a widespread local belief, Lone Cone is not a volcano. According to Melanie Kelman, a volcanologist with the Geological Survey of Canada, “Lone Cone is one of the Catface Intrusions, masses of quartz diorite that intruded the Westcoast Crystalline complex about 41 million years ago. So Lone Cone is definitely made of igneous rock but it is intrusive, not volcanic.” In lay terms, the rock that formed Lone Cone solidified deep underground.

When this mixed-up mass of geology named Wrangellia slowly collided with Laurentia, the collision caused earthquakes that crushed, folded, and fractured the rock. The sea bed between the two plates rose up with pressure so great that Wrangellia eventually split in two. The western section continued on its slow way 2,000 kilometres northward to form parts of Alaska; the rest remained in what is now southern British Columbia.

The story does not end there. Far from it. The most important part of Clayoquot Sound’s geological drama still lay in the future. After Wrangellia had adhered to what became British Columbia, huge submarine landslides, caused by the collision of tectonic plates, occurred in the area of the San Juan Islands, south of Victoria in Washington State. A mass of underwater rock and other material released by these landslides began moving northward, attaching itself to the western edge of Wrangellia about 55 million years ago. This Pacific Rim terrane, as geologists call it, includes material underlying Vargas Island and extending down to Port Renfrew. Highly visible outcroppings of this terrane appear along the Esowista Peninsula, on the stretch of land running past Long Beach down to Ucluelet, including Radar Hill, and also on various islands offshore, including Frank and Lennard Islands. About 42 million years ago the Crescent terrane, the last of the terranes making up Vancouver Island, and the smallest one, arrived to complete the puzzle; this now makes up the Metchosin area near Victoria. With these terranes in place, water, wind, waves, and, later, ice began attacking the land and busily wore away masses of rock and other material over the next 40 million years. A great deal of this eroded material settled on top of the Pacific Rim and Crescent terranes and piled up on the original bedrock surrounding places like Radar Hill.

The greatest transformation of Vancouver Island occurred in fairly recent geologic time. During the Pleistocene era, which lasted 200,000 years and ended only 10,000 years ago, four separate continental ice sheets covered almost the whole landscape of what is now Canada. Imagine ice up to 3,000 metres thick covering Canada from Newfoundland to Vancouver Island, and as far south as the mid-United States. The weight of such a mass of ice caused Vancouver Island to sink under the pressure, and as that immensely deep ice shifted back and forth it sculpted the land beneath. At one time the ice extended as much as ten to fifteen kilometres off the west coast of Vancouver Island. When it melted, as it did from time to time, contemplate the amount of water released, and how the land would have rebounded—a geological process called isostasy—as the weight of the ice lifted. During this melting process, sea levels stood an estimated ninety metres above today’s sea level, leaving only the highest points, such as Mount Colnett, Lone Cone, and Catface Mountain, emerging above the sea as small islands. The deep valleys and inlets of Clayoquot Sound; the huge boulders found on some beaches, called glacial erratics; the gouges, or striations, seen on some bedrock; the glacier-formed lakes such as Kennedy Lake; and the rocky soils all attest to the last ice age.

The flat land lying at the foot of the mountains and along the shore between Tofino and Ucluelet consists of glacial till, a mix of jagged rocks, sand, and silt making up what geologists call the Estevan Coastal Plain. Rivers flowing across that plain in front of the glaciers sorted some of the glacial material into rounded rocks and pebbles, as well as silt and sand, depositing it in deltas. Then the sea and the waves lashed the shore, further grinding the river deposits and creating long sandy beaches such as those at Wreck (Florencia) Bay, Long Beach, Cox Bay, Chesterman Beach, and MacKenzie Beach. Within Clayoquot Sound, away from the pounding waves, at low tide massive mud flats reveal an abundance of the finely ground material created during the post-glacial period.

Once the ice receded for the last time about 10,000 to 12,000 years ago, the newly uplifted land began basking in warmer temperatures, and plant life and animals began to reappear, eventually drawing the first human settlement to Clayoquot Sound. The earliest people may have migrated along the Beringia land bridge, a stretch of land across the present-day Bering Strait that once connected Asia and North America. They then could have made their way slowly down the coast and through North, Central, and South America on what anthropologists call the Coastal Migration Route. Other theories suggest the first inhabitants of North America arrived by sea via an ice-free coastal corridor along the edge of the Bering Sea about 17,000 years ago. Anthropologist Alexander Mackie argues this means “that all early period sites could be accommodated by people immigrating along the edge of the Bering Sea—previously thought by naysayers to be so inhospitable an edge of ice that no one could pass that way.”

Archaeological evidence suggests that people lived at Yuquot in Nootka Sound 4,300 years ago, in Barkley Sound 5,000 years ago, and in Bear Cove near Port Hardy 6,000 years ago. Others likely lived on the mainland coast of BC near Namu as long as 10,000 years ago. The village of Opitsaht, visible across Tofino Harbour, is believed to have been continuously inhabited for at least the past 2,000 years and possibly longer, given that Indigenous people have lived in Clayoquot Sound for some 4,200 years. Before the first contact with Europeans, the Indigenous population in what is now British Columbia is estimated to have been anywhere from 100,000 to 250,000, though more conservative estimates suggest only around 80,000. Of these people, an estimated 15,000 lived along the west coast of Vancouver Island.

One of the most important natural resources on the West Coast, enabling Indigenous people to live and settle here in such numbers, is the versatile red cedar (Thuja plicata), sometimes referred to as the “tree of life.” Massive red cedars thrive on this coast because of the moist climate, and for those living here, truly “people of the cedar,” these trees came to have great spiritual significance, as well as countless practical uses. Cedars provided material for dugout canoes, housing, paddles, clothing, baskets, rope; for many household implements; for medicine; and for ceremonial purposes. Planks of cedar could be cut from living trees, and the trees would survive; similarly, areas of bark could be stripped from standing trees with no harm done. Such “culturally modified trees”—or CMTs—can be found, still thriving, in the great forests of Clayoquot Sound, evidence of how a resource could be used wisely and well.

These immense cedars require an equally immense amount of rain, an inescapable fact of life here, especially in the winter. In this temperate rainforest, where the great cedars can grow to heights of sixty metres, heavy rains must fall, and they do. Tofino averages 202 days of precipitation a year and an annual rainfall of 3.3 metres—over ten feet. The maximum precipitation recorded at the Tofino Airport weather station for one day stands at 18.4 centimetres and on October 6, 1967, a record-breaking rainfall of 48.9 centimetres was recorded by the former weather station at the now defunct Brynnor Mine near Maggie Lake. By comparison, Vancouver receives a paltry one metre of rain a year and only averages 166 days of precipitation. As for the temperature, freezing temperatures and snow rarely occur at sea level, and the Tofino Airport weather station records an average of 364 days per year when the thermometer stands above freezing. January boasts a daily average minimum temperature of 1.2°C, while the summertime average stands at only 14.4°C.

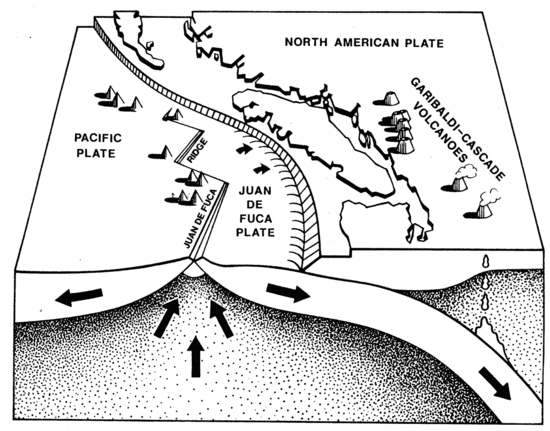

The location and geography of the West Coast present another drawback to people here, a potentially deadly hazard. Vancouver Island’s outer coast is located toward the northern end of the 1,100-kilometre-long Cascadia subduction zone, which extends up the coast from Cape Mendocino, California. Within this suboceanic zone, tectonic plates are constantly on the move, grinding past one another. The Juan de Fuca Plate, moving eastward, slips under, or subducts, the North American Plate, heading west. The continual slow-motion collision causes minor earth tremors, only detectable by delicate seismographs, almost every day. But the action taking place at the Cascadia subduction zone can, from time to time, cause calamitous natural disasters.

The danger occurs when the two plates become “locked,” causing pressure to build to the point where it must be released as a massive “megathrust” earthquake. Seismologists estimate that plate locking takes place every 400 to 500 years, meaning that the West Coast is constantly under threat from a “Big One.” Paleoseismic research has determined that thirty-nine megathrust earthquakes have occurred along the Cascadia fault in the past 10,000 years. Nineteen of these quakes ranged from 8.7 to 9.2 in magnitude on the Richter scale. Some of them took place 800 years apart, others less than 200 years apart. In geologic time, the last one occurred fairly recently, just over three centuries ago.

At about 9 p.m. on Tuesday, January 26, 1700, a massive earthquake shook the West Coast. The tremors lasted for several minutes, throwing people to the ground and continuing long enough for survivors to experience nausea and vomiting. First Nations oral history tells of whole villages being swept inland by a massive tsunami, or tidal wave, fifteen to twenty metres high, before the backwash took them out to sea. At Pachena Bay, just south of Barkley Sound and 130 kilometres south of Tofino, the wave swept the heavily populated Huu-ay-aht winter village of Clutus entirely out to sea. There were no survivors. Huge trees snapped like matches, landslides rained rocks and debris down slopes, and to the south a massive landslide completely blocked the mighty Columbia River, causing it to carve a new route for itself. In what is now Washington State, red cedar and spruce trees far inland died when sea water driven by the tsunami inundated their roots, leaving “ghost forests.” Destruction swept the land.

Ten to twelve hours later, the tsunami caused by this earthquake hit the shores of Japan, sending a five-metre wave crashing inland, killing thousands of people and causing widespread damage. Because no local earthquake had forewarned of the danger, the wave swept in unannounced. This has become known as the Orphan Tsunami.

The Japanese keep written records of earthquakes and tsunamis as far back as the 1500s, so seismologists have been able to calculate the time of the Cascadia Earthquake. By studying the cedar trees in the “ghost forests” in Washington state, researchers determined that their last growth ring dates back to 1699, the year before the earthquake. These findings coincide exactly with the First Nations oral traditions. A Cowichan tale recorded at the turn of the twentieth century and cited in the journal Seismological Research Letters describes the event. “In the days before the white man there was a great earthquake. It began about the middle of one night…threw down…houses and brought great masses of rock down from the mountains. One village was completely buried beneath a landslide. It was a terrible experience: the people could neither stand nor sit for the motion of the earth.” Another account, which appears in Kathryn Bridge’s book Extraordinary Accounts of Native Life on the West Coast, tells of the eradication of Clutus village near the mouth of Pachena Bay. “They had gone to bed, it was just like any other normal night. They were awoken during the night when the earth began to shake. The earth shook. Startled the people. They woke up. Thinking everything was over, they just relaxed. A little while later, the water came in real fast. Swept their homes away. Swept everything away. The water just came too fast. They didn’t have time to go to their canoes, so all the people that were living there were drowned. They were all wiped out.”

Brian Atwater’s book The Orphan Tsunami passes on information from James Swan, the first schoolteacher on the Makah Reserve on the Olympic Peninsula. On January 12, 1864, Swan recorded in his diary a conversation with Billy Balch, a Makah leader who lived near Neah Bay. Balch spoke of how all the lowland areas on the west coast of the Olympic Peninsula and Vancouver Island sank following the earthquake, with sea water inundating these areas after the tsunami. “That water receded and left Neah Bay dry for four days and became very warm. It then rose again without any swell or waves and submerged the whole cape and in fact the whole country except the mountains back of Clayoquot. As the water rose, those who had canoes put their effects into them and floated off with the current that took them north. Some drifted one way then the other and when the waters again resumed their accustomed level a portion of the tribe found themselves beyond Nootka where their descendants now reside and are known by the same name as the Makahs—or Quinaitshechat.”

At 5:36 p.m. on Good Friday, March 27, 1964, the largest earthquake ever to be recorded in North America shook Anchorage, Alaska, for four minutes. Measuring 9.2 on the Richter scale, the intensity of this quake is exceeded only by the Chilean earthquake of 1960, which measured 9.5. The Anchorage earthquake set off a tsunami that rushed south and west across the Pacific Ocean at speeds of up to 640 kilometres (400 miles) per hour. Of the 131 people killed by the quake, 122 drowned, not only in Alaska, but also in Oregon, where four people died, and California, where thirteen lost their lives. Though no deaths occurred in British Columbia, the tsunami hit Prince Rupert with a 1.4-metre wave just over three hours after the quake. Moving south it caused damage at Amai Indian Reserve at the head of Kyuquot Sound, at Zeballos, Hot Springs Cove, Tofino, and Ucluelet before surging up the Alberni Canal. There it washed away 55 houses, damaged 375 others, and left a swath of destruction. The cost to British Columbia is estimated to have been the current equivalent of $65 million.

Neil Buckle lived at Long Beach in 1964, and he recalled the tsunami in an interview with Joanna Streetly for her book Salt in Our Blood.

The slow grind of plate tectonic action remorselessly continues. Countries surrounding the Pacific Ocean and its so-called Ring of Fire keenly realize that any earthquake, anywhere in the Pacific Ocean, has the potential to create multiple tsunamis that could send waves from ten to fifteen metres high travelling at high speed right around the Pacific basin. Governments have established coordinated tsunami warning systems to alert people to potential danger in time for them to make for higher ground. Everyone living along the Pacific coast has now become aware that they must proceed to the highest available ground following an earthquake, in expectation of a tsunami. Nothing has made this clearer than the catastrophic earthquake of December 27, 2004, with its epicentre just off the coast of Sumatra. The subsequent tsunami, with waves up to thirty metres high, swept around the Indian Ocean, killing 230,000 people in fourteen countries. Most had no idea it was coming; at the time, no tsunami warning systems were in place in countries bordering the Indian Ocean.

In common with many communities along the outer coast of Vancouver Island, Washington, Oregon, and California, Tofino now has a highly sensitive tsunami warning system. Tofino’s system is recognized as a key “alarm bell” on the West Coast for detecting what experts term “tsunami events.” Once a tsunami hazard has been identified, sirens wail out, and residents should have at least fifteen to twenty minutes to get to higher ground, following the evacuation route signs along the roads. This system has evolved over a number of years, along with awareness among locals of the nature of the risk. On Vancouver Island’s west coast, tsunami warnings have been issued frequently enough in the past decades that people know the drill. Some take it more seriously than others, and every tsunami warning leaves a host of stories in its wake.

On May 9, 1986, an earthquake in the Aleutian Islands off Alaska prompted a tsunami warning for Hawaii and the Pacific coast of North America. When the warning came, four hours before the impending tidal wave, Tofino boat owners began taking their smaller boats out of the water and anchoring their larger ones in Browning Passage, aiming them toward the open ocean and hoping they would ride out the wave. RCMP cruisers and a helicopter, all with loud-hailers, ordered people to make their way to Radar Hill. Some patrons of the Maquinna Hotel beer parlour, choosing not to go, carried their drinks up to the roof and set up chairs to watch the excitement. About 600 Tofino residents eventually did make it to Radar Hill where, according to Frank Harper in his book Journeys, “a huge bonfire was crackling. Many car trunks were open and out of them had come the beer, the chips, the sandwiches, the juice, the blankets. Music was blaring from Sue Kimola’s fine speaker system and the people, even kids, were dancing, some frenzied, some mellow, all happy…At five minutes after ten, the great, bogus, two-inch tsunami warning was officially cancelled.” Following Russia’s Kuril Islands earthquake of October 4, 1994, Frank Harper related how Tofino handled the third tsunami warning in eight years. Even though rumours circulated about potential fourteen-metre waves, no one seemed unduly troubled. Tourists evacuated from their hotels milled around the Wickaninnish School, but few local people paid much heed to the warning.

More recently, on March 11, 2011, the 9.0 magnitude Tohoku earthquake, the world’s fifth most powerful since 1900, detonated seventy kilometres underwater off the northeast coast of Japan. The savage tsunami that followed sent forty-metre waves sweeping ashore, extending up to ten kilometres inland over the Tohoku area of coastal Japan. More than 25,000 people were killed or injured. Seconds after the quake, authorities issued tsunami warnings for the whole Pacific Rim region. Although some areas of the US West Coast suffered damage, Vancouver Island’s west coast escaped; a wave of only one metre came ashore.

The tsunami in Japan swept enormous amounts of debris out to sea, estimated at 1.5 million tonnes. It travelled slowly eastward on the Kuro Siwo current, and within months some of this flotsam began to appear on West Coast beaches, prompting the Japanese government to give Canada $1 million to help with the cleanup. Community groups along the West Coast began collecting the plastic bottles, Styrofoam, rope, fishing nets, and buoys that washed up. Everyone finding debris was required to report it to the appropriate authorities, but stories have eddied up and down the coast on the “kelp telegraph” of fascinating objects both large and small discovered and quietly retained. A small boat washed up on Long Beach, another near Hesquiaht Harbour, but the object most discussed in the media proved to be a motorcycle. A year after the tsunami, a Japanese shipping container turned up on an island in Haida Gwaii, containing a Harley-Davidson. The company managed to locate the owner, Mr. Yokoyama, in Japan; he had survived the quake but lost three members of his family. He declined the company’s offer to restore the bike and ship it back to him, and instead donated it to Harley-Davidson to be placed, just as it was found, in the company’s Milwaukee museum. Experts suggest that detritus from the tsunami will continue to land on West Coast beaches for years to come; so far, less has arrived than many people anticipated.

Knowing that a “Big One” could shake the West Coast one day, and that a tsunami could engulf the low-lying land along the shore, has become an accepted fact of life in the Tofino area. The seismological threat will never fade away. Immense geological upheavals shaped this landscape, the movements continue under the surface of the earth, and the people living here choose different ways of handling this reality. Some simply try to ignore the geological time bomb, others hope the “Big One” will be deferred indefinitely, while many spend time and effort educating themselves and their children and putting complex disaster plans in place for the public good. Whatever their attitude, everyone living here has an awareness of what could happen, and in a very special way they all know what it means to live on the edge.