Chapter 14: Community

“It was like there were three or four different villages,” observed Mabel Arnet, recalling Tofino in the 1920s and ’30s. “You knew you were in the Scandinavian group. Or if you were in the Scotch group, you knew you were in that group. Then there was the Indian village, which was hands off, and the Japanese people. You spoke with them but you didn’t associate with them socially.”

Several different worlds of people came together in Tofino. The Norwegians hailed from hard-working fishing and farming stock, stoic, unpretentious, and clannish, described by Dorothy Abraham as “tall, handsome women…and taller handsomer men”; the Scots and English groups included Gaelic-speaking Orkneymen, stubborn north country folk, and a handful of educated expatriates clinging to the notion of the British empire. The First Nations occupied separate spheres around Clayoquot Sound: on reserves, in villages, in schools, and in social groupings largely unknown, and unfathomable, to most outsiders. The numerous Japanese settlers who arrived in the area in the early 1920s, all of them fisher-folk, clustered in settlements known locally as “Jap towns” in Tofino, at Clayoquot, and at Ucluelet.

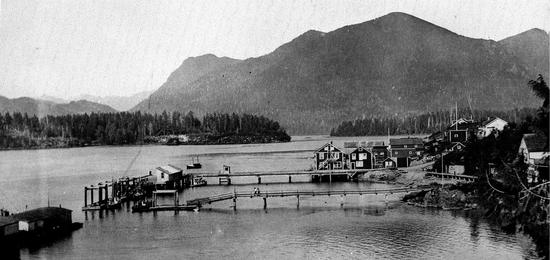

Despite their clear divides, everyone in the area knew each other, or knew of each other, at least by sight and by racial type. They knew each other’s boats; they met on the docks; they glimpsed each other at the stores, at church, at dances, and at special events, when they met in large numbers. Perhaps most importantly, they met for Clayoquot Days. From the first such event organized by Filip Jacobsen in 1896, sports and picnic days occurred at Clayoquot, initially on the May 24 weekend to celebrate Queen Victoria’s birthday; later on Dominion Day on July 1. Over the years this all-inclusive gala event became the best-loved and largest gathering in the area. “The morning of the 24th would be a time of great excitement,” Ronald MacLeod recalled in his memoirs. “Women packed picnic fare with families sharing the catering. New running shoes and light summer clothing for the children. Local fish boats swarming to the government wharf to pick up people to ferry them across to Clayoquot. Indians in flotillas of gas boats and canoes making their way to the event of the year.”

Recalling the Clayoquot Days of the 1920s and ’30s, Ian MacLeod described crowds of “twelve or fourteen hundred people from Tofino, Ucluelet, the reduction plants, the sawmills, the hatcheries, from Hot Springs Cove, Ahousaht, Nootka. There would be dozens and dozens of fishboats.” Students from Christie and Ahousaht residential schools also attended Clayoquot Days and the brass band from Christie School would play. The local Japanese community participated enthusiastically at Clayoquot Days, the children joining the races and enjoying “Canadian” ice cream cones, as the Christie School band entertained everyone with tunes like “Bicycle Built for Two.”

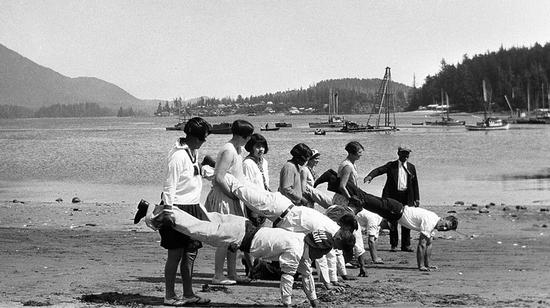

The races and sports competitions welcomed everyone. “Foot races for all, from the very young to the aged,” Ronald MacLeod recalled, “three-legged races, sack races, high jump, broad jump, hop-step-and-jump, pole vault, relay races, hurdles, tug-of-war, canoe races, upset-canoe races, skiff races, rowboat races, fish boat races—we had it all, even a greasy pole hung off the wharf and out over the water.” Epic feats of strength took place, the star event being the tug-of-war. Onlookers sang out encouragement to their teams—aboriginal chants, Norwegian Viking tunes, songs in Gaelic. By the late 1930s, according to Walter Guppy, during the short-lived mining boom, the tug-of-war pitted local fishermen against miners. The fishermen, accustomed to pulling heavy ropes, always won. In the sporting events, Ian MacLeod, age seventeen, excelled at the broad jump, making a twenty-one-foot (6.5-metre) jump. “But Isaac Charlie…he could make over twenty-four feet, twenty-five maybe. According to…the judges in those days, he broke the world record, but it was unofficial.”

“I won all the skip races,” Arline Craig recalled, with a laugh. “And there were softball games out on the sandspit—Ahousat against Opitsat, and a Ucluelet team too.” Because Arline so often rowed from her family’s home on Bond (Neilson) Island to Tofino, she also won the rowing races. She enjoyed seeing Mamie Dawley, Clarence Dawley’s wife, enjoying herself at Clayoquot Days, wearing a sun hat wreathed with flowers, greeting everyone, telling funny stories, and playing the piano at the hotel, where a good number of men could be found in the beer parlour, having come in “for a quick one when the throat got too dry from cheering and hollering,” according to Ronald MacLeod.

“All the Indians turned out in their war paint,” Dorothy Abraham reminisced, claiming that she too won a good many of the rowing races. To her delight, tennis arrived in Clayoquot by the late 1920s, becoming a regular feature of Clayoquot Days. When George Nicholson took over management of the Clayoquot Hotel in the mid-1920s, he convinced Walter Dawley to establish tennis courts on a “nearly level enough” patch of grass, fenced to keep the local bull away. Thirty-eight people signed up to join the tennis club, paying a dollar each, and according to Dorothy Abraham, membership soon swelled to seventy. The club bought “racquets and balls and shoes of every size, which were housed in the hotel so that anyone coming in off a survey or fishing boat would find everything provided.” During Clayoquot Days, tennis also took place on the curving sandspit.

“The beach was so much bigger then,” Lorraine (Arnet) Murdoch recalled, “Everything took place over on the beach, all the games, but in later years most of that beach just disappeared. It’s never been the same.” Barry Campbell, formerly of Parks Canada, and an authority on invasive species on the west coast, knows why. He holds Walter Dawley responsible. Determined to firm up the sandy shoreline, at some point during his years on Stubbs Island, Dawley planted a European species of beach grass, Ammophila arenaria. Instead of protecting the sandy beach, this grass rapidly spread, drastically reconfiguring the beach by directing most of the windblown sand out toward the northerly sandspit, at the cost of the crescent-shaped beach in front of the hotel and store. Aerial photographs of Stubbs Island from the early 1930s onward reveal immense changes in the shape of the beach and the length of the spit. By the 1940s this erosion had become so serious that the area in front of the store threatened to drop into the sea. Ruth White lived at Clayoquot during the 1940s, and in later years she observed how “the sea had gradually taken the buildings away.” Despite valiant efforts to shore up the area with hefty log cribs, the erosion continued, slowly undermining the old store completely. Eventually loads of rock were barged over to the island to protect the shoreline.

The same beach grass that caused this erosion subsequently spread down to the Wickaninnish Beach area, where the delicate ecosystem of the sand dunes behind the beach has been seriously harmed by this and another non-native beach grass, Ammophila breviligulata. These firmly rooted, fast-growing beach grasses trap vast quantities of sand on a rising fore-dune crest that now stands two metres higher than the dunes in earlier years. This crest rises in front of the natural dunes, depriving them of windblown beach sand they need to survive, and without which the native plants on the dunes die. Barry Campbell, who since his retirement has led heroic efforts to combat invasive species, initially went to war against Scotch broom and English ivy before tackling the invasive beach grasses. Volunteers and Parks Canada employees now follow his lead, patrolling the sand dunes and pulling up dense clumps of the destructive grasses, allowing the native beach grass (Leymus mollis) to return, along with endangered plants like the pink sand verbena.

Back in the 1920s and 1930s, the annual Clayoquot Days offered the largest local get-together, but residents enjoyed other comparable events from time to time. Sports days took place regularly at various First Nations villages and at the residential schools, baseball being particularly popular, and invitations often extended to all living nearby. Community picnics occurred: on Vargas Island, at Long Beach, at Echachis, and especially at MacKenzie Beach, organized by the Legion, the Japanese community, or the church. “A monster picnic was held at Mackenzie’s Beach recently, King’s Jubilee Day,” reported the Daily Colonist in May 1935, one of many such notices. Royal landmarks often inspired special events; the coronation of George VI in 1937 called for a day of “celebration sports” at Clayoquot, with prizes of “Coronation mugs, plates, cups and saucers and knives” donated by Robert Guppy, likely also responsible for handing out 100 coronation teaspoons to local schoolchildren.

A staunch royalist, formerly with the British civil service in India, Guppy came to Tofino with his wife and family in the early 1920s. Initially they settled on John Chesterman’s original property some distance from town, where the family endured their first winter in a leaky shack, tacking a leopard skin to the wall to keep out drafts, and placing a tiger skin on the bare floor. They then moved into Tofino, to a newly built house the family called “Clay Bank.” Robert Guppy returned to India for two years, leaving his wife, Winifred, in charge. Accustomed to having servants in India, she did not even know how to make porridge when she first arrived in Tofino, but she quickly adapted. On her husband’s return, he did not live with the family, preferring to live across the harbour on Stone Island, which he had purchased from William Stone. Guppy had a liking for islands: he also bought Strawberry and Beck Islands, renaming the latter Garden Island and establishing a hobby farm with cows and sheep and goats. He rowed into town almost every day with milk and produce for the family; his grandson Ken Gibson recalled watching the sun shining on his grandfather’s long, spooned oars as he feathered his way across the harbour, sculling in the manner he learned as a rowing blue for Pembroke College, Oxford. He would climb out of the boat and walk barefoot up the beach over the barnacles, in Ken’s memory always wearing the same outfit: short pants and a pith helmet.

Guppy’s attraction to the islands in Tofino Harbour has been shared by many over the years. From the earliest days of settlement, these islands have been repeatedly bought and sold. Thomas Stockham became the first island pre-emptor in 1898, promptly giving Stockham Island his name. Filip Jacobsen followed suit in 1899, pre-empting an island listed in the land records as “Clayquot Snd, small island,” at first simply called “Jacobsen’s,” and later Stone Island. In 1907, when James Beck and Thomas Gardhouse acquired an unnamed “Island nr Jacobsen’s I.,” it became Beck Island, and two years later Aksel Nilson pre-empted the island now called Neilson Island. Not all of these early island-seekers lived on their islands, though some did. In 1898, Mrs. Rolston recorded that “on all or most of these lonely scattered islands a family or bachelor is struggling to clear the dense bush and have a patch ready for vegetables or garden.” Notwithstanding the tidal rips, the winds and storms, the difficulties of moorage, and the lack of fresh water, the romance and charm of these islands have won the hearts of many over the years. Others considered island life and quickly abandoned the idea, among them Mike Hamilton, who briefly owned Strawberry Island in the 1920s. His fiancée, Mabel, liked the notion of living there, but Mike hastily sold the island, pointing out the practical difficulties of such a residence in a letter. “I was jolly glad even to see 150 bucks as the island would have been a white elephant,” he wrote, assuring Mabel that “we can get lots more islands bigger and better ones and close to hand.” They never did. Strawberry Island was later owned for many years by well-known diver and whale researcher Rod Palm.

Of all island dwellers in the harbour, none ever matched the impact made by Fred Tibbs during his years on his Dream Isle—also called Castle Island and Arnet Island. Before Tibbs headed off to serve in the Canadian Forestry Corps in World War I, he sounded one final blast on his cornet from his treetop platform, saying goodbye to his island domain. He told no one he was going, simply boarded up the windows of his wooden castle and left. On one window, up in the tower, he painted a picture of a beautiful princess; some say she looked like Olive Garrard. No one knew at the time, but Tibbs harboured secret romantic attachments, not only to Olive but also to Alma Arnet. Some thought he also fancied Winnie Dixson. “Oh he tried all of us, all the different girls,” Winnie later commented. “I didn’t have much interest…I had about 300 chickens.”

Neither Alma nor Olive had any idea what lay ahead. Tibbs had made his will before setting off to war, leaving the island “and everything thereon, excepting the house and ten feet of land on either side of the house site,” to Alma Arnet, “because she’s the nicest girl I know.” He left the house and contents, except for his gramophone, to Olive Garrard, “because it was built for her.” If Olive married, the house should go to Alma “if she is still single.” Returning intact from the war in 1919, Tibbs resettled on his island and resumed his land-clearing, his gardening, and his risky experiments with explosives. On New Year’s Eve in 1919, he tried to explode dynamite from his tree platform thirty metres up in the air, to “blow the old year to the four winds,” but the explosion did not go off with the bang he had hoped, the dynamite being frozen. In his wooden castle, Tibbs entertained visitors who came to listen to his gramophone and drink cocoa, and he often went to Tofino to collect mail and to “have some music, as there are two or three damsels here who play very nicely.” He attended community events and dances—though he never danced—and he also took up a new job. Rowing his skiff around the harbour, he tended the navigation lights, coal-oil lanterns mounted on tripods on wooden floats. Every second day when the lanterns required refilling, Tibbs would tie up to the floats and clamber on to fuel the lights.

In early July 1921, Francis Garrard noted that Tibbs had been blasting rock on his island; “he had got badly powdered and had been quite ill from the effects.” Immediately after this, on July 4, the Clayoquot Hotel went up in flames. Along with every other available man, Tibbs rushed over to Stubbs Island to assist in fighting the fire. The following day he went out to tend the lights, but after landing on one of the floats, his skiff drifted away. He dived in to swim after the boat. Not realizing what had occurred, a Tla-o-qui-aht man who saw the empty skiff towed the boat to Opitsaht. Tibbs turned and made for the nearest land, on Stubbs Island. Perhaps overexertion, combined with the effects of the dynamite powder, had weakened him, for although he was usually a powerful swimmer, the effort proved too much. “He made the spit alright,” Bill Sharp recalled. “He crawled up on the sand and lay there.” A Japanese fisherman alerted the authorities; the telegram sent from the Clayoquot police to their superiors in Victoria read “Frederick Gerald Tibbs found exhausted on beach at Clayoquot by Jap fisherman early this morning.” Tibbs could not be revived. “When the Doctor arrived…,” wrote Francis Garrard, “Tibbs was already dead…it was a very sad affair.” The gravestone for Frederick Gerald Tibbs stands in the old Tofino cemetery, on Morpheus Island.

Following Tibbs’s death, the Garrard and Arnet families reached an agreement about his unusual will. Olive Garrard relinquished her share of the inheritance, his castle home, to the Arnets, and Dream Isle became Arnet Island. A group of men went over to the island shortly after Tibbs’s death to cut down the thirty-metre-high “tree rig,” deeming it unsafe, and as time passed the clear-cut island slowly greened over. A few others attempted to live on the island, renting out Tibbs’s castle, but the place became associated with bad luck and sudden death. According to Anthony Guppy, after several unfortunate fatalities and mishaps there, the “strange little castle remained unoccupied for a long time…People began to believe it was haunted. It became a sort of game for young people to go over there, get inside, and make the most hair-raising ghostly noises.” The stories of Tibbs lingered and grew; by the late 1920s, “Fred Tibbs had already acquired the gloss of a legendary figure,” according to Guppy. The year after Tibbs died, Alma Arnet married Harold Sloman; Olive Garrard also married in 1923. Had Tibbs lived a bit longer, perhaps he would have reconsidered his will. He certainly would have enjoyed the livelier social scene that began to emerge in Tofino in the ensuing years.

In the winter, with picnics and sports days off the agenda, lively gatherings in Tofino were few and far between. For those seeking excitement, dances occasionally took place over at the Clayoquot Hotel, and the beer parlour there always welcomed thirsty men. Following the fire in July 1922, determined to lose no drinking time, Walter Dawley promptly rebuilt both the hotel and beer parlour, just as he had following an earlier fire in 1908; the second time around, having learned from experience, he had the place insured. Yet despite the busy scene in the beer parlour, and the comings and goings in the hotel, on the whole Dawley’s establishment held limited appeal for townsfolk, especially families and young people. In the dark rains of winter, they remained grounded in Tofino, hemmed in by thick bush, their scattered homes joined up by muddy tracks and dimly lit by kerosene lamps. A “mug up” of coffee with the neighbours, getting together to listen to one of the few radios in town, arranging meetings to voice community concerns, and attending church services provided the limited distractions. “Do you know, they had never had a bazaar, or even such a thing as a whist drive!” wrote Dorothy Abraham in amazement after she and her husband left Vargas Island and moved into town in the early 1920s.

Social life in Tofino took on a fresh dimension in 1923 with the construction of a new community hall. The original hall in town had been built before the war by a group of settlers, all of them shareholders in the undertaking. Following the war, the Great War Veterans’ Association of Tofino purchased this hall for its clubhouse, calling it the Clayoquot Sound Great War Memorial Hall. Because some townspeople felt the Legion Hall, as it became known, functioned more as a club for its members than as a community hall, a group formed to build another hall. The Tofino Community Hall Association raised funds for a larger structure by selling shares, with a minimum of five and a maximum of 100 shares per person. Volunteers built the new hall in a series of work bees, within months producing a simple and solid building: wooden floored, red roofed, painted cream, with one large hall, a smaller anteroom, and a covered porch. The hall officially opened in mid-July 1923, with its first whist drive and dance. Over the years this hall hosted countless badminton tournaments, strawberry teas, box socials, whist drives, even early movie shows, including Felix the Cat and Charlie Chaplin, magically brought to life courtesy of Mike Hamilton’s hand-cranked projector. The hall became famed for hosting elaborate New Year’s masquerades and wedding receptions—yet in its glory days, nothing the Tofino Community Hall offered could eclipse the Saturday night dances.

Saturday after Saturday, decade after decade, the dances continued, the social heartbeat of the town. In the afternoon before a dance, the big wood stove would be lit, and willing young men fetched the piano from a nearby home. This instrument could not be left in the hall because the damp spoiled the tuning. An accordion and a violin often joined the piano, and in a pinch, a gramophone played. The musicians tuned up and never faltered. “Three waltzes, three fox-trots, three polkas, a sequence that repeated over the course of the evening,” Jan Brubacher wrote in an article for The Sound. “With a whooshing of dresses and a tap, tap, tap on the hardwood floors, Norwegian traditions of dancing passed down through the community with dances like the Hambo and the Schottische.” And Dorothy Abraham enthused, “The Norwegians were the most wonderful dancers.”

Men lined one side of the hall on the big benches, ladies on the other, while at the back, tables groaned with the food laid out for the dancers. Alcohol not being permitted in the hall, those who wished to drink stashed their liquor in the bushes, and men would pop outside from time to time to their designated spots; no one would ever touch another’s bottle. “If you were a lady,” Vi Hansen observed, “you did not step outside.” Everyone came to the dances: children and old people; loggers and fishermen passing through; people off visiting boats; miners and prospectors who hiked down from the mines for the weekend; all the girls in town, dressed in their finest; and sometimes, depending on the state of the road and the season, even people coming up from Ucluelet.

Special occasions called for extra dances; Walter Guppy recalled a “cougar dance” in the mid-1930s, held after a group of men tracked and shot a trapped cougar that had dragged itself up a creek, trap and all. No single man could claim the bounty, so they shared it, rented the hall, invited everyone, and danced away the proceeds. The prospector Sam Craig trekked into town from Bear River one weekend, expecting a dance. Finding none planned, he started asking friends if they planned to come to the dance that night. “Dance? There’s a dance?” Word spread, and within hours the event became a certainty, a piano had been moved to the hall, food and alcohol mysteriously appeared, and the dancing began. The following Sunday mornings could be tough, especially for the men who had to move the piano back to its home and then make the return trek to their mines, or go out on their fish boats, heads throbbing.

The promise of entertainment could entice party-going locals a good distance out of town. At Calm Creek, the Darville family liked to have parties, despite being some twenty-three kilometres from town. On December 22, 1925, the Colonist reported: “An enjoyable party and dance was given at John Darvil’s mill at Calm Bay and, although…a furious southeaster prevailed at the time, the young folks braved it with true Canadian determination.” Three years later, in April 1928, the Darvilles hosted a masquerade ball at the Tofino Community Hall. “About 150 guests were present. Costumes worn by Miss Ethel Darville, Tyomi Onami, Miss Audrey Coton, the Misses Nicholson and Wallis, Andy Gump, Mrs McKenzie, ‘Mickey’ Nicholson, Mrs E W [Dorothy]Abraham, the Darville brothers, Mrs Norman Thomas, Miss Winnie Dixson, Daphne Guppy, Mrs Trygve Arnet.”

In 1929 the Tofino Community Hall Association and the Great War Veterans’ Association of Tofino reached a compromise. Rival events had sometimes occurred on the same night at their halls, so the two groups agreed to hold dances on alternate Saturdays, an arrangement that lasted for a number of years. The Legion Hall also hosted the occasional vaudeville show, and it acquired the added attraction of a poolroom and a barber shop, both operated by the one-legged “Peg” White. From time to time, Legion members raised the question of whether they should obtain a beer licence, but the red tape proved too daunting, and they settled for temporary liquor permits at special functions.

Weightier political matters preoccupied Legion members much of the time. Made up of returned veterans from World War I, the Clayoquot Legion included Murdo MacLeod, who had been seriously wounded in action twice, as the first president. Other members included Harold Monks, Fred Tibbs, Harold Sloman, Rowland Brinckman, Jack Mitchell, Wallace Rhodes, Alex MacLeod—to name only a few. In 1921, this group accepted Lillian Garrard, who had been a nursing sister overseas, as an honorary member, though she no longer lived locally. The Legion took its responsibilities seriously, using its lobbying power to ensure returned veterans received jobs on the fisheries patrol, at the lifeboat station, or in other government-funded positions. Legion meetings addressed many matters of concern to the community, helping to defend the Tofino post office in 1921 when it faced the threat of closure, and initiating discussions about how to obtain better medical care in town. Legion members also participated energetically in the perennial campaign for a road.

For decades, west coasters had hankered for a road. The notion of linking to Alberni via a permanent route across the mountains had persisted since the earliest days of settlement. Back in 1896, Clayoquot storekeeper Filip Jacobsen petitioned for funds to improve the trail leading out of Ucluelet toward Long Beach. The provincial government allocated $500 in funds, keeping eighteen men and a foreman busy working that winter on a section of the path “a distance of 3 miles [4.8 kilometres]…building four bridges…and making a trail…passable for either horse or cattle.” In 1898 another $500 kept the project moving slowly forward.

Ten years later the Colonist expounded on the importance of a proper connection between Ucluelet and Tofino, stressing the potential tourist benefit. The newspaper declared that the imminent arrival of a railway in Alberni would draw visitors down the Alberni Canal to Ucluelet, and then up to Long Beach—if a road existed. Later that year, the village of Ucluelet acquired more funds to improve the connection to Tofino and, “using wheelbarrows, picks, shovels and crosscut saws, the only equipment affordable from the paltry government grants,” kept a crew of men busy, achieving little more than allowing surveyors to mark where the road eventually would run.

Despite such spurts of activity, prior to World War I the “road” linking Ucluelet to Long Beach consisted only of straggling stretches of overgrown trail through the bush, with occasional lengths of corduroy logs laid over boggy sections. Yet the dream of this and future roads persisted, fuelled by news of the forthcoming “Canadian Highway.” On May 4, 1912, near Alberni, road crews began “surveying the new road from Sproat Lake to Long Beach…The Long Beach road will connect up at Alberni with the Canadian highway, so that in the very near future this highway from Victoria will find a true seaboard terminal on that ocean, at one of the finest beaches in all North America”—or so declared the Colonist on May 9, 1912.

Given such optimistic forecasts, in the pre-war years settlers and land speculators began snapping up every available section of land between Ucluelet and Tofino. In 1910, over 200 land transactions took place in the Ucluelet/Tofino area, many at Long Beach: pre-emptions, purchases, Crown grants, and a handful of mining claims and timber licences. By 1912, over 300 transactions occurred. Many parcels of land changed hands several times within a few years, and a significant number of people acquired multiple adjacent tracts of land; short-term land speculation was rife. By contrast, a handful of earnest settlers tried valiantly to settle on their newly acquired lands, working every daylight hour to clear land, packing supplies on their backs over rough trails if they were not on the waterfront, and labouring against considerable odds to keep their families fed and their livestock safe. The coming of the war put an end to many of these early homesteads, and the land rush petered out. In 1918, only eight land transactions took place in the entire Clayoquot District, extending from Hesquiaht to Ucluelet.

While the pre-war fervour persisted, the Colonist breezily reported in 1914 that construction continued on the Ucluelet/Tofino road. Because motor cars had by then arrived in BC, the paper noted that “Long Beach, which will be connected with Tofino before long by the road, is the finest stretch of hard sandy beach...and will someday be the scene of automobile racing such as is practiced on the Florida beaches.” Given that no one in Tofino or Ucluelet owned a car until the early 1920s, such a notion must have seemed foolish nonsense to most locals.

Postwar road-building efforts saw little progress and increasing local irritation. Leading the charge against ineptitude and wastefulness, the Great War Veterans’ Association of Tofino convened a public meeting in July 1920. “It appears the road foreman is frittering away the money by making trails to land which is neither in occupation or cultivation,” snapped the Daily Colonist. Even so, postwar road work did provide sporadic employment for locals. When Harold Monks returned from the war, he initially worked at the Tofino lifeboat station for $105 a month, but in May 1920, when the lifeboat service cut its winter crew for the summer months, he took a job with the Tofino road-building crew, receiving $76.43 for eighteen-and-a-half days’ work.

In 1921, to press for more action on the road, James Sloman, Francis Garrard, and others from Tofino joined forces with a group from Ucluelet and travelled to Victoria to lay their case before the Good Roads League, an organization created by cyclists in Rhode Island in 1892 to lobby for improved roads. A Tofino branch of the BC Good Roads League formed in 1922, with Captain John W. Thompson as secretary. Known as “Cap” Thompson, and considerably older than most war veterans, he became one of Tofino’s most beloved citizens. Thompson claimed to have been the oldest person serving in the Canadian army during the war; he had lied about his age, knocking off a couple of decades, and joining up in 1918 at the real age of sixty-eight. Renowned in Tofino for greeting every coastal steamer at the dock, Thompson’s flower garden boasted dahlias as big as dinner plates and prize gladioli. Local children vied to help out in the garden for a nickel a time.

The short-lived Tofino Good Roads League put out a publicity leaflet mincing no words. After a spot of purple prose extolling the town and its location—the “verdure-clad fairy islands” of the harbour, and the “sunlit summer seas that lie embosomed among the everlasting hills”—a blunt subheading came straight to the point: “What the West Coast Needs: Good Roads. More Settlers. Much Advertising.” Then another headline, “What we want You to Do,” and the command “Boost For a Road—Yell For a Road.” While the Good Roads campaigners set their sights on a connection to Alberni, the first step still remained completing the laggardly connection between Tofino and Ucluelet. Yet despite the local campaigners winning a meaningless “Good Roads Pennant” in 1923, the road extended only three kilometres outside Tofino at the end of that year.

By 1925 the road from Tofino stretched nearly to Long Beach, and local optimists hoped that Tofino residents wanting to picnic there would no longer have to rely on the tides to make the journey. Until this time, excursions to Long Beach had to coincide with high tide so people and supplies could be unloaded from their boats in Grice Bay before walking the trail across the peninsula to the beach. The return trip had to meet the next high tide in the evening; missing the tide meant a very messy trek through the mud flats of Grice Bay out to deeper water. Helen Malon reported in her diary how she was “a little late in coming back and had to walk three or six hundred yards [275 to 550 metres] in the mud, barefoot, not at all a pleasant experience.”

Anthony Guppy recalled the Tofino road of his childhood days as “nothing more than a rough gravel trail that began at the government dock in the village and wound its way through the village into the woods. This trail...continued on for some three more miles [five kilometres]...then turned into a sort of rough road bed that led through the forest to Long Beach.” Overgrown with flourishing vegetation, this “so-called road remained an almost unusable trail, winding up and down steep little hills and through marshy land.” In winter, any car foolish enough to venture out of town “would sink to its axles in the soft brown quagmire” before reaching Chesterman Beach.

Slogging through thick mud is an apt metaphor for the road. The Tofino–Long Beach section became infamous for its washouts, axle-deep mud, and waist-deep sinkholes. After that came the easy part—driving many kilometres on the sands of Long Beach before joining up with the better, but still very rough, road to Ucluelet.

Rough or not, vehicles began to make the journey. In early June 1928, the Daily Colonist noted that “H.T. Fredrickson brought the 1st tourist car over the road from Ucluelet to Long Beach,” and two months later Peter Hillier of Ucluelet seized the opportunity and established an occasional bus service to carry sightseers from Ucluelet to Long Beach in the summer months. Tom Scales and J.R. Tindall of Vancouver drove a motorcycle at 145 kilometres per hour across the sands of Long Beach in August 1930, proclaiming it “the finest speedway ever seen.” The following month, Arthur Lovekin, who had bought 244.5 hectares of land fronting on Long Beach a few years earlier, had a car shipped to Ucluelet. After driving it up to Long Beach, he took a spin along the sand accompanied by his wife and daughter, driving at speeds up to 112 kilometres per hour. The Lovekins had built a large house and extensive gardens on their property, and used the place as a summer residence for thirty-five years; Lovekin confidently expected development would follow them to Long Beach, once declaring it to be “the playground of the Western World.”

Travelling by road in and out of Tofino remained a nightmare for many years. Ronald MacLeod remembered that “by the late 1930s, if the summer was dry, a truck could make its way to Ucluelet with great difficulty but only if the driver had an axe to cut poles and branches to lay across the sinkholes.” Yet residents stubbornly clung to the road dream. After all, ever since 1926 a sign had stood near the government dock proclaiming the location to be the “Pacific Terminus of the Trans-Canada Highway.” Surely one day this would come true. Meanwhile, the sign became a favourite rubbing post for the local cows roaming the town. On one occasion it disappeared and emerged mysteriously in Ucluelet, and for many years it provided photo ops for tourists disembarking from the Princess Maquinna. Tom Gibson, later the mayor of Tofino, repainted the sign year after year, keeping the dream alive. With the formation of the Tofino Board of Trade in 1929, yet another lobby group took up the cudgels in the fight for a road link out to Alberni. This road campaign still had thirty long years to run; it needed all the fresh energy it could muster.

Rowland Brinckman dashed off these lines about the road with his usual insouciance. One of Tofino’s most popular residents, Brinckman neatly captured the spirit of the town in his tongue-in-cheek writing and quirky paintings. An energetic organizer, he established a dramatic society and put on many light-hearted skits, plays, and concerts in the town, writing the material himself and uniting the community in a new manner. He designed and painted elaborate backdrops for these events, wild, colourful flats of scenery featuring imaginary monsters. The children loved him. On summer evenings they would wait till “Brinky” went on his night watchman shift at the lifeboat station, and they would visit him there, begging for stories. He introduced the little crowd of MacLeod boys to a hitherto unknown world, reading them the recently published Winnie the Pooh, among other books. “He gave us a sense that there was a world beyond our cocoon called Tofino,” Ronald MacLeod wrote, marvelling at “the rich flow of wonders that sprang forth from his brain.”

A gifted artist, musician, and writer, Brinckman’s charm and keen humour won the hearts of everyone he met during his time in Tofino. Even the most phlegmatic Scot had to admit he was not bad—for an Englishman. His puckish wit emerges in his illustrated map of Clayoquot Sound, still hanging in the Tofino municipal offices. The map lists the languages spoken in town—including Gaelic, Norwegian, and Japanese—and its intricate cartoon sketches and captions poke fun at “fierce fishermen” and the “Presbyterian Mission (very holy)” at Ahousaht. Off Lennard Island, in exposed waters, Brinckman wrote: “Here ye sick transit spoileth ye gloria Monday,” punning on the Latin sic transit gloria mundi.

Born in Kilkenny to a privileged Anglo-Irish family and raised in England, Brinckman came to Canada in 1914, perhaps to free himself from the pressures of his background. His father, a career military man who served in many colonial campaigns, received the Order of the British Empire for his services during World War I. His Irish grandfather, John Elliot Cairnes, an economics professor at both Queens University in Belfast and Trinity in Dublin, gained renown for his writings on economics and the slave trade. Brinckman arrived in Vancouver and found work as a farmhand. A year later he signed up to join the Canadian Expeditionary Force, giving his occupation as “Architect.” He spent the rest of the war overseas, serving in the Machine Gun Corps, and taking part in the battle of Vimy Ridge in 1917. On his return to Canada in 1919, he worked for a while as a clerk in Vancouver before heading to the west coast with some friends, seeking adventure.

According to Gordon Gibson, Brinckman and his friends arrived on the coast in 1923 in their small six-horsepower boat. They settled initially at White Pine Cove, on the southern shore of Herbert Inlet, near where dozens of marines and sailors began their infamous land attack on the Ahousahts following the Kingfisher incident in 1864. Before long, these inexperienced Englishmen were cutting shingle bolts, enthusiastically and ineptly, for the Gibson Lumber and Shingle Company at Ahousat. The hard labour of felling trees, then bucking and splitting them, proved too much for Brinckman’s friends, who retreated to Vancouver, but he stayed on for a number of years, settling on land he pre-empted at the head of Matilda Inlet on Flores Island, and spending a great deal of time with the Gibsons in Ahousaht, where he worked in the sawmill and in the cookhouse.

The tough-talking, hard-drinking Gibson boys, four brothers famed for their risky and ambitious ventures, had never seen the like of Rowland Brinckman. “[He] brought an entirely new dimension to our lives,” wrote Gordon Gibson. “He was a music buff and a fantastic cartoonist…an avid reader and had a standing order with a bookstore in Vancouver to send him novels as soon as they were available.” Thanks to Brinckman, the Gibson house rang to the music of Gilbert and Sullivan, and the works of P.G. Wodehouse and Arnold Bennett entered the home. Evenings around the piano, rousing singsongs, and hours listening to the gramophone became part of their lives. “He was such a gracious man that all of us were grateful for the warmth and new interests he brought into our lives.” Possibly Brinckman encouraged Gordon Gibson’s unexpected passion for poetry. A colleague once described Gibson as “such a complex character…a person who could talk like a muleskinner…and in the next breath recite verse after verse of the most complex poetry without missing a word.”

Brinckman no doubt encouraged the impromptu dances that often occurred at the Gibson household on Saturdays, when the teachers and staff from the Ahousaht mission came over, or whenever the Princess Maquinna called. “In the early days the Maquinna tied up overnight at Ahouset,” Alder Bloom of Tofino recorded in his memoirs, “and the Gibson boys would escort the passengers across the island, on plank walks that they had built over the wet ground, to the local hot springs for a refreshing dip, then they would return to their home where they danced in their living room to the wee hours of the morning.” If young single ladies were aboard, “lady tourists” as they were known, taking the round trip up the coast and back, the dancing became even merrier. “Up the coast we were good dancers,” Gordon Gibson wrote. “We would dance all night when there was a fiddle and enough light.” But all too soon the Princess Maquinna would be on her way, with a shriek of her whistle, manoeuvring slowly away from the dock at Matilda Creek—no small feat in the dark or the fog, because the ship had to back down the narrow inlet for about a kilometre before she had enough room to turn around and head off.

When little Mary McKinnon was growing up in Ahousaht in the 1920s, she would walk over to see Rowland Brinckman, and he showed her the children’s books he was writing and illustrating. Her mother, Gladys (Izard) McKinnon, formerly a concert pianist in England, bitterly resented being transplanted to Ahousaht, where her husband worked for the Gibsons after losing his family fortune, but she took comfort from finding in Brinckman someone she could talk to about books and poetry and music. Fearing tuberculosis, Gladys did not allow Mary to play with Ahousaht children; the solitary little girl could hear their laughter and see them playing, but she had to make her own entertainment. She collected shells and learned to row all by herself in a little skiff in the harbour, but her best moments came when she could visit the Princess Maquinna, for Captain Edward Gillam always allowed her to come aboard and have a meal at his table. Other than this, her great delight lay in visiting Brinckman and hearing his stories.

After moving into Tofino, Brinckman lived in a cottage opposite the present-day Maquinna Hotel. He soon befriended the entire town, including the sometimes testy George Nicholson, who had moved to Tofino in 1930 after managing Walter Dawley’s hotel and beer parlour for several years. Nicholson took over the Tofino Hotel, formerly owned by Hans Hansen. Not renowned for a sense of humour, Nicholson suspected Brinckman was in cahoots with the local teenagers who, on occasion, enjoyed playing pranks. One Halloween proved particularly lively: pranksters tied Nicholson’s doors shut from the outside, and boys throwing firecrackers managed to damage a small totem pole Nicholson had erected outside the hotel. The figure had a prominent penis, which strangely vanished. The enraged Nicholson took up his shotgun and let loose a volley, and some of the shot peppered the backside of one of the boys. A local feud led to charges of assault being brought against Nicholson. The Ahousaht magistrate came to town to hear the case, but dismissed the charges.

Despite any differences, Brinckman and Nicholson, as Great War veterans, addressed each other as “comrade” at the local Legion gatherings, and they collaborated successfully on several dramatic productions. The most ambitious occurred in May 1931 when, backed by the Legion and the BC Historical Association, they mounted an elaborate re-enactment of Captain Cook’s landing at Friendly Cove in 1778. Described in the West Coast Advocate as “by far the most elaborate performance ever attempted locally,” the pageant aimed to be a “performance identical in every detail of the actual occurrence.” This extravaganza took place on a Tofino beach, likely Tonquin Beach, and according to the Daily Colonist practically everyone in the district attended, including “hundreds of Indians from nearby reservations.” Featuring accurate period costumes for Cook and his men and for the Indigenous characters, and with “exact detail paid to the Indian language of the time,” the pageant included a boat landing, scenes on board ship and in war canoes, and song, dance, and dialogue. Large flats painted by Brinckman depicted the scenery of Friendly Cove, and the two producers had obtained elaborate props: “a priceless collection of old totems, masks, cedar bark blankets, monster mounted eagles that moved their wings and heads, and many other old valuable Indian articles.” Many of these items were loaned by people from Opitsat; others came from George Nicholson’s private collection.

The cast numbered twenty-two, including five elders from Opitsaht, named by the Colonist as “Chief Joseph, Queen Mary, Paul Avery, Iskum Jack and Chief E. Joe.” Chief Joseph and Queen Mary carried great authority locally, being the best-known Tla-o-qui-aht elders; their participation in the pageant added considerably to its status. Nicholson described them “both arrayed in their war paints…and clothed in bearskin rugs.” Queen Mary nearly stole the show, holding everyone spellbound “for as long as she continued her friendly gestures in both song and dance.” Not having a sufficient number of Indigenous participants to represent the Nootka people, “a band of young ladies from Tofino [acted] the part of the Nootka tribe.” This explains the distinctly Norwegian appearance of some of the “Nootka” girls in surviving photographs. George Nicholson took the role of Captain Cook, and the part of Chief Maquinna, according to Nicholson’s account of the event, fell to Chief Joseph. The Colonist reported that Brinckman played Maquinna, but he more likely acted as Maquinna’s interpreter during the long speeches made by Chief Joseph in that role.

The pageant opened with Chief Maquinna and his men discussing rumours of a big “devil man” coming to threaten their way of life. A white sail then appeared out at sea, and the “Nootka tribe” danced defiantly, interrupted by gunfire. After an encounter at sea, a sailors’ hornpipe, more Indian dances, and an elaborate exchange of gifts, the boat sailed into “Friendly Cove,” peaceful accord was established, and Cook and his men came ashore to a welcoming ceremony. A concert in the Legion Hall followed the pageant, and according to Nicholson, “Chief Joseph and Queen Mary put on a song and dance act that certainly brought the house down, and called for several encores.”

The historical importance of Captain Cook had been commemorated on the west coast well before the famous pageant. August 12, 1924, saw the unveiling of a cairn at Friendly Cove to honour Cook’s “discovery” of Nootka Sound. Several dignitaries from Victoria participated, including Lieutenant Governor Walter Nichol, Dr. C.F. Newcombe of the Provincial Museum, and the influential historian F.W. Howay of the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada. The group travelled to Friendly Cove by steamer, its numbers swelling en route as local participants in the event came aboard, including a group of schoolboys from Kakawis. “I joined the Princess Maquinna at Tofino, there was quite a party aboard,” Dorothy Abraham enthused, delighted when her newly formed Brownie troupe received a Union Jack from the dignitaries on board. When the crowd of visitors arrived at Friendly Cove for the unveiling of the eleven-foot-high (3.3-metre) cairn, Father Charles Moser acted as interpreter between the Lieutenant Governor and Chief Napoleon of Yuquot. This cairn joined another commemorative cairn already in place nearby. The earlier one, known as the Meany monument, had been erected by the Washington State University Historical Society in 1903, through the efforts of history professor Edmond Meany.

Following the 1931 Captain Cook pageant, the area witnessed yet another attempt to make the road between Tofino and Long Beach passable in winter. With thousands of unemployed men left idle by the Great Depression, the Canadian government set up relief camps in remote locations to keep them busy on public works projects—and also to keep them out of the cities, fearing the spread of communist agitation. Camp 101 went up near Chesterman Beach, alongside the road, to house 100 men, mostly fishermen from Tofino, Ucluelet, and Ahousaht. Another section of the relief camp went up at Long Beach. The young Guppy boys often went out to the Chesterman camp and chatted with the men, who “would tell us tales about wild animals around the camp...hungry mosquitoes, atrocious food and damp beds in damp tents...the place was driving them crazy.” The men laboured at ditching, grading, and gravelling the Tofino–Ucluelet road, doing all the work by hand with pick and shovel, the only machine available being an old Ford truck. They earned twenty cents a day plus room and board. The Guppy boys also visited the Long Beach camp once, meeting the camp foreman, who whiled away his time building a highly finished Welsh dresser from wood collected on the beach. “I doubt the crew there did much work,” wrote Anthony Guppy. “I think they likely spent their time walking the sands and discussing ways to reform the capitalist system when and if they ever got back to civilization.”

Following the first winter, local people began to reach out to the unemployed men in the camps, offering support and entertainment. This followed a letter to the Colonist asking “if anyone would donate a battery radio for use at Long Beach Unemployment Camp; there are now over 100 men there, and they have very little contact with the outside world. Mail delivered twice a week, and no form of entertainment.” The men received a radio, and Captain Neroutsos of the Canadian Pacific Coast Steamship Service sent three bundles of magazines. Later, “a football game between the Camp and Opitsat Indians was played, ending in a win for the road camp by 4 goals to one,” reported the Colonist on March 29, 1932. “In the evening the men were entertained to the Legion show and dance.” A month after that, some local entertainers took their show out to the camp; performers included Rowland Brinckman, Rev. John Leighton, George Nicholson, and Eileen Garrard. Such diversions must have been more than welcome at the dismal work camp, although other excitements did occasionally present themselves. On August 24, 1932, a Boeing five-passenger flying boat crash-landed on Long Beach. Pilot Gordon McKenzie had taken off from Nootka for Vancouver but flew into fog, forcing him to make an emergency landing. Swells caught the plane and carried it out into the surf, rolling it over and over, as men from the relief camp rushed to the rescue, fixing ropes to the plane, and the Tofino lifeboat hurried to the scene. The pilot escaped serious injury.

For many years, a silent undercurrent of activity all along the west coast involved selling booze. Since 1854, selling alcohol to Indigenous people had been against the law, a prohibition based entirely on race that gave rise to decades of bootlegging, along with persistent, unavailing efforts to stop this activity. During the sealing era, schooner captains frequently provided alcohol to bribe hunters to sign on; in later years, bootleggers sold whiskey or moonshine from their motor launches, anchoring off the villages and waiting for customers to come out in their canoes. At the Clayoquot beer parlour, some customers regularly bought beer for Indigenous people, who would wait outdoors for the surreptitious handover.

During the years of prohibition in British Columbia, from 1917 to 1921, alcohol could not legally be bought or sold at all, inspiring highly inventive ways of obtaining liquor. After 1920, with the introduction of prohibition in America, many Canadians entered the lucrative rum-running trade, a cross-border traffic that thrived until US prohibition ended in 1933. Tall tales of illicit booze sales in and around Tofino have been told for decades, mostly unsubstantiated, always colourful, and generally leaving more questions than answers: about bottles of booze hidden in the piano at Clayoquot; about a large stash of liquor in a disused fishing scow on the waterfront; about scowloads of rum leaving Tofino for offshore vessels; about one of the prettiest houses in Tofino having bottles hidden in a little-used cellar. Impossible to verify and improving with age, such stories live on. When America ran dry, various local citizens probably did have extra liquor on hand, perhaps a fair amount, to sell to visiting American boats, either at the local docks or offshore. As Douglas Hamilton commented in his book Sobering Dilemma, “The illicit booze trade was a small entrepreneur’s dream.”

In 1932, Tofino officially incorporated as a village, a coming-of-age process enabling the community to govern itself. A board of three commissioners became the first town council; Jacob Arnet acted as chairman of the commission, working alongside John Cooper and Robert Guppy. Wilfred Armitage served as town clerk. In the ensuing years, most prominent local citizens served as commissioners at various times. At first, meetings took place monthly in the home of one or other of the commissioners, the minutes recorded by hand in imposing ledgers. The commissioners gravely discussed all matters of local concern, large and small. The safety of pedestrians came up at one of their meetings during Tofino’s first winter as a fully fledged village. The commissioners agreed to ban vehicles from Main Street because of its deteriorating condition, and to allow people to walk safely. An overly cautious decision, considering the town had, at most, half a dozen vehicles.

The question of health care in Tofino frequently surfaced as a matter of concern for village leaders. Medical care in the area had never been adequate, and a series of different physicians came and went at Clayoquot in the early years of the century, followed by the establishment of the short-lived Methodist hospital on Stockham Island. After only a few years of operation, that hospital closed around 1912. Father Charles Moser noted its demise in his diary: “The Mission was given up by the Methodists. The Hospital used to be a Hotel was bought by Chief Joseph for something like $20.00 for the lumber that was in it.”

No doctor lived in Tofino until 1912, when Dr. Douglas Dixson arrived; he remained the only doctor permanently based in Clayoquot Sound for nearly twenty years. Appointed to provide medical care for aboriginals on the coast, Dixson faced an impossible job. He ranged from Tofino to Kyuquot, travelling continually up and down the coast by rowboat, fishing vessel, and coastal steamer, attending to the residential schools and the villages. Whenever he could, Dixson hired the Agnes, a vessel owned by the Grant family and regularly used to transport mail and workers up Tofino Inlet to Grice Bay and the Clayoquot cannery. Every month Dixson received his “Indian cheque” for around forty dollars, and filed his “Indian report” and “Schools report.” His duties included checking children for contagious ailments and deciding if they were fit for admission to residential school. Dixson also cared for the Tofino townspeople and for scattered settlers requiring his help on a fee-for-service basis.

Dixson’s surviving diary from 1916 lists all his patients by name or nickname: Topsail George, Big William, Bachelor Tom, Bill Spittal, Reece Riley, Lockie Grant, and many others, along with their various ailments. Phthisis appears often—a term used for tuberculosis—along with measles, mumps, whooping cough, syphilis, pneumonia, rheumatism, teeth extractions. In his travels, Dixson visited the workers at the copper mine in Sydney Inlet, settlers on Vargas Island, the storekeeper at Nootka—and he made regular runs to the hotel at Clayoquot to see patients, followed by a meal at the hotel and a few shots of rum or whiskey. The diary indicates that he sometimes received urgent summons to visit isolated homesteads, like that of the Rae-Arthur family in Hesquiaht Harbour, and on one occasion to visit a serious burn victim at Ahousaht. Bad weather could easily prevent him making such emergency calls; far too frequently his boat had to turn back.

Dixson also checked the Tofino schoolchildren for signs of tuberculosis. The schoolteacher, Katie Hacking, who later married Harold Monks, recalled the doctor’s much-dreaded visits to the school. At first she failed to understand the children’s unhappiness when they knew he was coming. Eventually she learned they did not like how Dixson used the same tongue depressor on all of them. She suggested they bring an implement from home, perhaps a teaspoon or butter knife, to serve as a personal tongue depressor. On the day of the health checks, Dixson expressed amazement at all the cutlery the children produced. When Katie explained, he expostulated, “But I do nothing of the kind! I use one end of the depressor for the girls, and the other end for the boys!” Described by Dorothy Abraham as “a funny old boy,” easily overexcited and unable to suture a badly cut hand, Dixson did not inspire confidence as he grew older. He remained in Tofino until just before his death in 1932, succeeded by Dr. A. Swartzman.

It became increasingly clear that one doctor could not adequately serve the area, and that sending seriously ill people out by boat to hospital in Alberni often imperilled lives. The lifeboat, fisheries patrol vessels, lighthouse tender, and coastal steamer all dealt with medical emergencies, but they could not always respond quickly enough, nor could they provide proper care to patients en route. Dr. John Robertson, who took over from Swartzman in the autumn of 1934, set about making changes. On contract to the Department of Indian Affairs, he was primarily responsible for serving Indigenous people, but inevitably he served everyone who needed him. He recalled his early experiences in an article for Canadian Hospital in June 1937. “When I first came here… I found it necessary to do emergency appendectomies in the homes with no running water and no means for safe sterilization.”

According to George Nicholson, who often ferried the doctor to visit patients in remote areas during his five-year tenure in Tofino, Dr. Robertson performed a total of three appendectomies in the Tofino Hotel, one in a floating logging camp, two in private homes, and four at the mission schools. “Many a mulligan pot had to improvise as a sterilizer,” wrote Nicholson. Robertson’s young wife, Marguerite, assisted at one of these appendectomies, carried out by gaslight on a table in the Tofino Hotel. With no sterile linen available, Marguerite turned to her trousseau because her tea towels “were quite new.” She put them in a disinfectant solution, donned rubber gloves, and laid out surgical instruments—including bent forks in place of retractable forceps. The surgery proceeded, and the patient recovered. Robertson conducted another of these emergency appendectomies on the kitchen table in the home of Murdo MacLeod, who stoically held the gas lamp for the doctor during the operation on his young son Ronald.

From the moment of her arrival in Tofino, Marguerite Robertson learned to expect the unexpected. She arrived after her husband, disembarking on Christmas Eve 1934 from the same boat carrying the much-anticipated order of Christmas liquor, eagerly awaited by revellers at the dock. Her introduction to Tofino came the following morning in church, when even the minister, Rev. John Leighton, felt the effects of too much Christmas cheer. He left the service halfway through to be quietly sick in the churchyard and returned with a smiling apology. Dearly loved in the community, “Padre” Leighton could do no wrong in the eyes of his parishioners. Another memorable event occurred when Queen Mary and Chief Joseph of Opitsaht came to visit Marguerite. As a sign of her status and wealth, Queen Mary arrived wearing three hats. Marguerite presented tea and cookies to her visitors; when she offered a refill, Queen Mary declined, “but I would have if you’d had coffee.” Queen Mary came to know Dr. Robertson well; he gave her the empty hypodermic glass vials from his surgery, and she made them into a treasured necklace. She wore it on special occasions, including the day in August 1936 when she and Chief Joseph greeted the visiting BC premier, Duff Pattullo, on the dock at Tofino.

At first, Dr. Robertson saw patients in a tiny damp shed on the waterfront. He had to coat instruments with Vaseline to stop them from rusting, he fetched water in a pail, and he kept the wood stove going in a space too small for an examining table. A frail partition that did not reach the ceiling divided the examining area from the cramped waiting room; sometimes the doctor asked patients to wait in Towler and Mitchell’s store next door, to afford privacy for others. This store, formerly Sloman and McKenna’s, had changed hands twice during the 1920s, before being purchased in 1928 by two former employees of Walter Dawley, Fred Towler and Jack Mitchell. Although on the site of the original store in Tofino, Towler and Mitchell’s was no longer the only store. Shortly after Duncan and Maude Grant arrived in Tofino in 1916, they built a store on pilings at the end of the government wharf, just a short distance away. Grant’s store operated until 1930, when former cannery employee Sid Elkington took it over, changing the name to Elkington’s.

The doctor’s “office” perched on the boardwalk known as Grice Road, near the homes of several early settlers. First John Grice built his house on Grice Point, later the MacLeods, Larkins, Rileys, and others built their homes along the waterfront here. In 1927, John Cooper, originally at Long Beach, built his new Tofino home just above the road, and shortly after, Cooper opened the Imperial Oil marine station on the waterfront below. Harold Monks later bought Cooper’s home and business. With the oil station, two stores, post office, mining recorder’s office, several homes, doctor’s office, and government wharf all in close proximity, this became the commercial centre of Tofino. And as daily gathering places in town, nothing beat the conviviality of the stores. Often a good number of townsfolk could be found hanging around the potbellied stoves, talking politics and local gossip with whoever came by. First Nations families also whiled away their time in the stores, including Chips George and his wife, who sometimes spent entire days at Towler and Mitchell’s. Comparing prices between the stores provided a special pleasure; if tinned corn, print fabric, lamp wick, hair ribbon, or flour varied by as much as a cent, word would spread at once. Being asked to wait in the store, watching all this activity, never seemed a hardship for Dr. Robertson’s patients.

The doctor, though, knew he needed a facility offering patients better care and a guarantee of privacy. This became particularly clear to him when treating venereal disease. Both gonorrhea and syphilis were rife on the coast, cutting across all populations of fishermen, settlers, and aboriginals. Syphilis also affected children, who could be born with the condition. Records survive of one little girl at the Ahousaht residential school who received eight treatments for congenital syphilis before dying of tuberculosis at the age of only eight. Her case was not unique. For adults affected by venereal disease, particularly rampant during fishing season, the doctor had to put aside a good deal of time for the required treatments. Robertson had so many cases of syphilis coming his way that at certain times of year he dedicated every Friday to treating the condition, privately dubbing the day “Dirty Friday” as a steady stream of patients attended his clinic for IV treatments of the pre-antibiotic drug known as Salvarsan, compound 606, or arsphenamine.

Knowing that local women could act as nurses to their own families, Robertson believed that, with ingenuity and volunteer help, Tofino could support a small hospital. It would mostly serve emergency cases, using relatives to nurse the patients, and the doctor would rent a section of the building for his offices. Robertson discussed the idea with community leaders and found eager local support. The idea quickly took hold, leading to one of the most extraordinary volunteer efforts the town ever witnessed. From the outset, everyone understood that this hospital would be a labour of love, relying on local generosity and volunteers. It would serve a wide area and a wide range of people, from Ucluelet to Estevan Point, a population of about 900 settlers and 1,400 Nuu-chah-nulth people.

Formed under the Friendly Society Act of British Columbia, the Tofino Hospital Society took on the challenge of fundraising. Government funds would cover 40 percent of the cost; the rest had to be raised by the society. Local merchants came forward to donate goods, services, and money, and many businesses and individuals from outside the area also contributed. Rowland Brinckman, a good friend of the Robertsons, donated the land for the hospital building. Well before construction began, the redoubtable Ladies’ Hospital Aid group sprang into action, numbering from twelve to twenty-five members at different times. They first met in February 1935 and decided to purchase fabric and start sewing all the bed linens, pillowcases, gowns, and curtains. Their subsequent fundraising efforts included raffles, bake sales, fashion shows, bazaars, and dances. For decades to come the Ladies’ Aid remained a local force like no other, tirelessly raising money for specific hospital expenses. “It was amazing,” Marguerite Robertson recalled, “how everyone pulled together. Whites, natives, Japanese—everyone.” By the spring of 1935, work had begun, described in the Daily Colonist on May 2: “Community spirit working overtime, all the men-folk of Tofino district turned out each day to help clear the site for the proposed hospital…a very few days had the property transformed ready for building.”

To contribute to the fundraising, Rowland Brinckman organized a “monster vaudeville show.” The curtain rose at the Legion Hall on May 18, 1935, for the first of two packed-house performances, admission twenty-five cents. The audience included Indigenous folk and Japanese, visiting fishermen, lighthouse personnel, dozens of people from Ahousaht and Ucluelet, plus, on the first night, officers, crew, and passengers from the Princess Maquinna. The steamer changed her schedule, staying in port overnight for the spectacle. Following the second night’s performance, a huge dance took place in the community hall. Over 200 people attended, the Ladies’ Aid served supper, and musicians from the lighthouse tender Estevan provided the music. The vaudeville show included an “Indian war dance in full costume,” led by Chief Joseph of Opitsaht and performed by eight dancers. The talent also featured an accordion concert, and a trapeze act by the doctor, who hit a rafter and broke a rib in the excitement. The centrepiece, a play written by Brinckman, poked fun at what he defined as the main interests of Tofino inhabitants: gas engines, fishing, rum, and sake, the powerful rice wine made by local Japanese.

Everyone in Tofino knew about, and many happily shared, the abundant homemade sake around town, thanks to the Japanese residents. Yoshio (Johnny) Madokoro recalled the local “part-time law-man” who would drop by to drink sake with his parents. “A few times when someone came in from ‘outside’ he would drop a warning and all signs of the illegal sake-making would magically disappear.” In a memoir written for his church newsletter in Toronto, Tatsuo Sakauye recalled proudly that his mother made “the best booze on the West Coast.” Mrs. Sakauye brewed her sake twice a year in her home at Eik Bay, each batch requiring two forty-five-kilogram sacks of rice. No one ever sold sake; it featured as a gift on special occasions. Padre Leighton had a great fondness for it, consuming impressive amounts without ill effect. Bill Spittal, the old prospector who lived on Tofino Inlet, became friendly with the Kami family, and their sake very likely inspired him when the family asked him to name their newborn baby. Spittal named him Napoleon Bonaparte Kami.

Fundraising efforts for the hospital continued unchecked. According to George Nicholson, the Vancouver radio announcer Earle Kelly raised many donations. Known as “Mr. Good Evening,” and sometimes hailed as Canada’s first personality broadcaster, Kelly regularly mentioned the Princess Maquinna’s progress up and down the coast during the 1930s. His comments about the vessel he dubbed “The Good Ship Maquinna” won him many friends on the coast. From 1929 onward, west coasters tuned in to catch his nightly broadcasts on radio news service CKCD from Vancouver, straining to listen through the scratchy reception. As Kelly wound up his show, he bid goodbye to all his listeners “on the land, on the water, in the air, in the woods, in the mines, in lighthouses,” often adding “and especially to everyone on the Good Ship Maquinna. Good night.” Marguerite Robertson recalled these broadcasts vividly: how everyone would tune in at 6 p.m. on the days the Maquinna was due; how “Mr. Good-Eve-en-ing” spoke so slowly and formally; how he spoke always of Clay-oh-kwot—never “Klakwot”—and To-fee-no. In Tofino, if the boat was delayed unloading freight at You-cloo-let or at Clay-oh-kwot, hearts would sink: “‘Oh dear, canned sausages for dinner again,’ we’d say.”

By October 1935, the Tofino Hospital Society agreed that to keep costs down, the hospital would have no furnace but would be heated by wood stoves and a coal-fired kitchen range; it would not be wired for electricity, but would instead use Coleman lamps; and the upper floor would be finished at a later date. Construction began in 1936, all done by volunteers. Every day, groups of women prepared large noonday meals for the workers. Within a few months the building became a reality.

In the early years, patients came to hospital with their own “nurse,” usually a relative, and paid one dollar a day to be there. The Ladies’ Aid did the mending and some of the cooking and cleaning, and continued to raise funds for whatever need arose. Marguerite Robertson assisted at surgeries in the new hospital, lighted by battery-powered headlamps and performed on an operating table built by the doctor. She would cautiously administer ether or chloroform, with her husband intoning “Drip, drip, drip,” but before long, trained nurses came to help. One travelled over from Clayoquot, where her husband ran a mink farm, and the nurse from the residential school at Ahousaht also came when needed. Bessie Jean Banfill wrote of one occasion when she received a telegram at Ahousat to come at once. The lifeboat from Tofino came to fetch her, her severe seasickness en route to the hospital eased by the “cheerful spirit of the huge, big-hearted, life-saving crew, as they vied with each other to serve me.” She assisted at the surgery, and the local telegraph operator, who had never before witnessed an operation, also helped. Within a few hours, the nurse found herself back in the lifeboat, heading to Ahousaht, while the patient recovered in hospital, attended by “a local Norwegian girl and a relative.”

Rowland Brinckman never saw the hospital completed. He had accepted a job in Ottawa, working for the National Theatre. Excited at the prospect of new horizons, he sold his possessions and came to stay with the Robertsons in April 1936, just prior to his departure. To the dismay of all his friends, the severe cold he had been nursing worsened into pneumonia. Despite the efforts of the doctor, assisted by Hilmar Wingen, who provided oxygen from his machine shop, Brinckman’s condition deteriorated. “We couldn’t save him,” Marguerite Robertson recalled sadly. He died in their home. “And bitter tears we children wept,” wrote Ronald MacLeod.

Unable to attend the funeral, Marguerite stayed home with her new baby. The rain lashed down in torrents, water poured off the handmade casket in the Tofino lifeboat, and the solemn cortege of boats heading to the cemetery on Morpheus Island looked so dismal that she made her husband promise if anything happened to her he would “never take [her] body to that dreadful place.” Not everyone shared her dread of the Morpheus Island cemetery, and the place still exerts a strong hold on local imagination. Twenty-two people are buried there, including John and Jane Grice, Jacob and Johanna Arnet, John and Annie Eik, Fred Tibbs, Harold Kimoto, and several members of the Garrard family. The island ceased to be used as a cemetery in the late 1940s, with the opening of a cemetery outside Tofino, near the airport.

With the building of the hospital and with a growing local economy, Tofino came into its own as a hub for the west coast. The population in town stood at around 250 by the late 1930s, nearly one third of the people in town being of Japanese descent. Well-established and well-respected, the Japanese had become an integral part of the local scene in Tofino. Given their growing families and increasing involvement in the community, their future here looked bright.