Chapter 12: Disconnection

“Mr Guillod [the Indian agent] used to say to the Indians that there would not be any white people here,” Chief Jimmy Jim of Ahousaht stated in May 1914. “They will not come here; it is too wild, he said, and white people would not use this land. That is what Mr. Guillod told my father.” The chief was appealing to the officials of the McKenna–McBride Commission, trying to make them understand the Ahousahts’ need for access to their traditional lands, and expressing his people’s baffled disbelief at the changes being forced upon them. The commission, a group of government appointees, travelled the province for several years, visiting Indian reserves, hearing testimony from local leaders, considering requests for additional lands, and conferring with Indian agents, with the declared aim of settling once and for all the boundaries of Indian reserves.

Jimmy Jim’s testimony to the commission reflects similar statements from many other Indigenous leaders in Clayoquot Sound and throughout the province. “Now the Indians are beginning to know...,” he said. “Today they know they have so small a piece for my people. Some white men have 200 acres [81 hectares] or more, and some have 80 acres [32 hectares]. And why have we such a small place here. We were born here, and white settlers have a bigger place. Why don’t we have bigger lands?”

The McKenna–McBride Commission hearings took place when “the life of the Nuu-Chah-Nulth people was uprooted, causing many different cultural ‘breaks,’” as Ahousaht chief Earl Maquinna George stated in Living on the Edge. The population had dramatically decreased, and almost every bond in traditional Indigenous society had suffered some form of “cultural break”: certain customs, such as the potlatch, had been banned; the people had lost traditional forms of barter and exchange for a cash economy; children were facing removal to residential schools; nations were gradually losing their languages; and perhaps most confusing and alarming of all, they were losing traditional territory and fishing grounds. The Nuu-chah-nulth’s access to their traditional lands became radically restricted as settlement expanded, and the patches of land set aside as Indian reserves bore little relationship to the long-established understanding of traditional territories.

Most of the limited reserve lands set aside for Nuu-chah-nulth people of the west coast date back to the 1880s. Between 1882 and 1889, over the course of several trips to the area, Indian Reserve Commissioner Peter O’Reilly allotted reserves to all the different tribes on the coast, based on the assumption that people who relied on fishing did not need much land. When in the field, he worked fast, rarely spending more than a few days setting out reserve lands for any given tribe, carefully scheduling and planning his visits, attempting to see local authorities and chiefs, and briskly assigning the reserve lands as he saw fit.

In 1882, O’Reilly visited Barkley Sound and the Alberni area, and in the space of a week designated thirty-six reserves, almost all linked to sites of traditional fisheries. If Europeans happened to be living in a potential reserve area already, their claim to the land took precedence. Even so, O’Reilly assured one of the local chiefs that “the Government were anxious to secure to them all their fishing grounds.” In 1886, O’Reilly arrived in Hesquiaht Harbour, where he allotted five reserves. Three years later, in 1889, he spent most of June and early July in and around Clayoquot Sound, determining the reserve lands for the Tla-o-qui-aht and Ahousaht people.

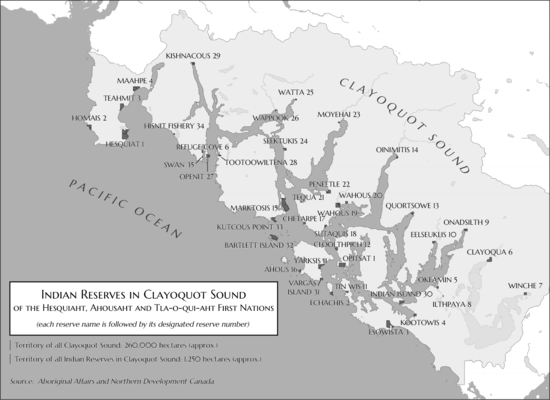

For the Ahousaht, including the Manhousaht and Kelsemaht bands, he designated nineteen reserves; on the map these appear as a scattershot of small dots, mostly situated at traditional village sites and fishing grounds. The largest of the Ahousaht reserves, the traditional winter village site of Maaqtusiis in Matilda Inlet on Flores Island, measured 105 hectares, the next in size being 57 hectares at Wahous, located at the mouth of the Cypre River. Most of the Ahousaht reserves measured between 9 and 20 hectares; the three smallest measured 5, 4.5, and 2.5 hectares. O’Reilly allotted ten reserves for the Tla-o-qui-aht people, the two largest being 73 hectares at Opitsaht and 44.5 hectares at Clayoqua at the mouth of the Clayoquot River. The smallest Tla-o-qui-aht reserve, Ithpaya, measured 1.4 hectares and was on the “northerly shore of Kennedy Lake at the rapids,” according to the Schedule of Indian Reserves. The Okeamin reserve, a traditional fishing village on the eastern bank of the Kennedy River near Tofino Inlet, measured 9.7 hectares and had fourteen houses. As Douglas Harris pointed out in his book Landing Native Fisheries, this last reserve included for the Tla-o-qui-aht the right to fish in the river from the boundary of the reserve downstream for about a kilometre and a half to the tidal waters of the Tofino Inlet. Yet only a few years after these reserves were established, the Clayoquot cannery began operating in that fishing area, having acquired 64.7 hectares of land nearby, specifically to access this same fishery. So the fishing rights granted to the Tla-o-qui-aht people on the Kennedy River, where they had always fished, proved far from exclusive. O’Reilly later denied he had allocated an exclusive fishery.

By the time his term as Indian Reserve Commissioner came to an end in 1898, Peter O’Reilly had established 654 Indian reserves throughout British Columbia, bringing the total number to just over 1,000. With these reserves set aside on the West Coast and elsewhere in the province, government authorities and incoming settlers perceived all the rest of the land to be entirely unoccupied, thus available for settlement and for industrial exploitation. As Cole Harris wrote in Making Native Space, “Opening land for others to own is what Indian reserves were intended to do.” With the diminishing population of Indigenous people officially corralled within their small, assigned spaces, others now took over the vast remaining spaces of British Columbia.

Few colonists ever questioned this; one notable exception was Gilbert Sproat. In 1860, Sproat overruled the objections of the Sechart people in the Alberni area when he arrived with two armed vessels and some fifty men to take possession of land at the head of Alberni Inlet, enabling Captain Edward Stamp to establish a sawmill and a settlement. Governor James Douglas contributed the gunboat Grappler to add to this show of force, and to ensure the takeover of the land. “We often talked about our right as strangers to take possession of the district,” Sproat later wrote. While he believed that strangers did have the right to purchase the land, he recognized that at Alberni “it was evident that we had taken forcible possession of the district.” His book Scenes and Studies of Savage Life, published in London in 1868, reveals how, as time passed, he felt increasing concern about the “injuries and discouragements [that] come upon the aborigines, through the occupation of their country by the settlers. Their hunting and fishing places are intruded upon, their social customs disregarded, and their freedom curtailed, by the unwelcome presence and often unmannerly bearing, of those who are stronger than themselves.” In 1876, Sproat became one of the first three Indian Reserve Commissioners, appointed as a team, before Peter O’Reilly took over. Sproat’s increasing sympathy for the Indigenous point of view, and his assumption that Indigenous people should control the fisheries on their reserve lands, made him unpopular with government authorities. The three-person team disbanded in 1878, and Sproat continued as the sole commissioner. Considered too generous with his land settlements, he was forced to resign in 1880.

Peter O’Reilly initially appeared to share Sproat’s assumption about Indigenous people controlling their fisheries, but later he backed away from this position. In the 1880s the federal government began the process that ended in its taking over legal control of all fisheries, relegating all First Nations to a subsistence food fishery. The result, according to Cole Harris, is that “many Native people today live in settlements that once depended on fisheries, and on reserves that were allocated to be fishing stations, but, because of one licensing scheme or another, have access to only a small share of the fisheries at their doorsteps.”

In May 1914, the evidence given by Nuu-chah-nulth leaders at the McKenna–McBride Commission’s hearings at Opitsaht, Ahousaht, Hesquiaht, and Nootka consistently focused on a few main points. They all wanted more lands made available to them; they wanted to be free to harvest cedar trees for canoes and bark; above all, they expressed confusion, dismay, and sometimes anger about the restrictions on hunting and fishing, particularly fishing. Chief Napoleon of Nootka spoke for all First Nations on the coast when he told the commission “I don’t want any white men to…[take away] any of our land or fishing places or hunting places, because God made us this way and put us in the places where we live.” A young man at the time of the McKenna–McBride hearings, Chief Napoleon had been educated at Christie Indian Residential School at Kakawis on Meares Island. In 1908 he married Josephine, who also had attended Christie School, in a lavish Christian ceremony at Friendly Cove, the first such ceremony for an Indigenous leader on the west coast. Like the older Nuu-chah-nulth leaders, Chief Napoleon pointed out very basic problems concerning his people’s access to resources, including how they could no longer even gather logs from the beach freely. “The white people that are around here,” Chief Napoleon explained, “…stop us taking the logs and timber along the beaches. [They] don’t want us to take any of that lumber or any of the wood.”

The testimony of Chief Billy of Ahousaht fills several pages in the published record from the McKenna–McBride Commission. He repeatedly stated his fear that white men would destroy the houses of his people, giving examples from Vargas Island of how their houses had been either used or destroyed by settlers. He also told of other Indigenous houses on non-reserve lands that had been there for many years for seasonal use when the people fished there; he feared their removal. He commented on the increasing scarcity of fish; he described many traditional fishing sites and their various uses; he solemnly stated, “My people are not going away from the places where they used to live.” He also specifically asked the commission about beach wood on Vargas Island, and whether his people could take wood from the beaches in front of the new settlers’ homesteads: “One time we went on to the beach and picked up a piece of 2 X 4 lumber and he [“Mr. Abraham”] said to us you can’t take that—that lumber belongs to me. And don’t you come on this beach any more, because that is my beach. Therefore I want to know when he buys the land does he get the beach?” The chairman of the commission replied, “If a man buys a piece of land the beach on which it fronts belongs to him. And it is the same with the Indian on his reserve.”

In his testimony, Jimmy Jim of Ahousaht spoke of access to good timber: “The white settlers can take up timber limits on the lands, stay here in Clayoquot a few years, and after they have cleared up a little place of farm land, they sell it for a good many hundred dollars and sometimes thousands of dollars and then get away…we know that us poor Indians here have nothing. We cannot sell any timber land or we can’t down the timber on our own reserves. It is just like holding us as blind men.” He elaborated: “There are a few cedar trees around the shore from the bark of which we made baskets. We cannot do that anymore. We cannot cut down the cedar trees so that we can make canoes or can get the bark. What are we going to do for a living?” He spoke of the restrictions imposed on his people’s use of their traditional summer camp area on Kennedy Lake; they were no longer permitted to fish or even trap there. The land around Kennedy Lake, and all of its rich resources, had always been central to his people’s lives; here stood their heartland, their major source of sustenance. Their increasingly curtailed access to the lake and its resources, and to many other traditional sites, baffled and angered them. “We wish to have a place to make canoes and some other things…We want to ask you to be allowed to do the same as the white men are doing here with their lands and timber limits.”

The Nuu-chah-nulth leaders all faced questions from the commission about how they used their various reserve lands, and why they required the additional lands they were requesting. All of their answers related to long-established patterns of fishing or sealing or some form of harvesting from the sea or land: they explained their connection to these lands in terms of access to different salmon runs or to clams, berries, seal, halibut, cedar trees. They described how and where they harvested and processed these and other resources, season by season. Every village site or summer fishing camp or stream had a story behind it of long-standing, usually seasonal, occupation and specific usage. When asked to explain why the Ahousahts had so many different traditional places for fishing in one area, Chief Keitlah gave the obvious reply: “So that we could go from one place to another. That is how we got the fish.” With some twenty-four fishing streams and rivers in their territory, the Ahousahts simply followed the salmon, travelling anywhere from eight to thirty-two kilometres from the main village of Maaqtusiis. The name of the village reflects these movements; it means “moving from one place to another.”

Chief Joseph of Opitsaht expressed his perplexity at no longer being allowed to fish from the 44.5-hectare Clayoqua reserve. “They put us in jail for it,” he stated. The restrictions on fishing at Kennedy Lake dated back to October 1905, when John Grice, as fisheries officer, and fisheries inspector Edward Taylor first informed the local people they could not continue to fish there. Father Charles Moser attended the meeting with the fisheries inspector on October 30, 1905. His diary reports that Taylor forbade the Tla-o-qui-aht to fish in the lake and also banned “the use of nets (they still could use spears) in the river coming from Kennedy Lake. The Indians were wild and used insulting language to the Inspector.” Taylor also banned traditional fish traps in the river. In subsequent letters to Taylor, John Grice commented that the ban on fishing in Kennedy Lake seemed a “desperate remedy” and that “I came in for my share of abuse.”

Nine years later, at the time of the McKenna–McBride Commission hearings in the area, fishing in Kennedy Lake remained contentious. Tensions increased following the establishment of the hatchery on the lake in 1910. Limitations on fishing in the Kennedy River had become even stricter, the Clayoquot cannery effectively having taken control of that fishery. Kelsomaht Charlie testified to this before the commission, saying, “I want to tell you that Mr. Grice does not like to see the traps in the creek so we took them down, and Mr. Grice used to go down to [Harlan] Brewster and tell him to get the fish right in the creek, with a seine…There used to be lots of fish in the creek, but since the cannery has come on that creek there is no fish there at all.” Jasper Turner of Opitsaht also gave evidence: “The canneries get all the fish and we have nothing for the winter. Of course we cannot live on the white people’s food, we have to live on our own.”

The McKenna–McBride Commission also scrutinized the monetary value of reserve lands, and the value of the extra lands being requested by the various tribes. At the Tla-o-qui-aht hearings, John Grice gave evidence about this, generally valuing reserve land for the tribe at twenty to forty dollars per acre (less than half a hectare), with the exception of Esowista, the seven-hectare (seventeen-acre) reserve out at Long Beach. “That is the most valuable, for this reason,” Grice explained. “There is a lot of talk about the CPR building a hotel on Long Beach which practically adjoins this particular reserve. A section was sold, consisting of about 70 acres, for $5,000 not very long ago. And I should think the value of this 17 acres would be $4000.” The short-lived rumour about a CPR hotel at Long Beach quickly died away, along with rumours about a railway line extending to Long Beach. Without such speculative value, Grice estimated the Esowista reserve to be worth only thirty dollars per acre.

The Nuu-chah-nulth leaders who gave testimony to the McKenna–McBride Commission requested that specific areas of land, clearly identified, be granted to them. Like his fellow chiefs, Chief Joseph of Opitsaht spoke with straightforward eloquence. “I am the Chief here. I am going to tell you what I have in my mind…I have 221 Indians and this place is too small for that number of people. I am very anxious to get more land for my people.” His requests for land on behalf of the Tla-o-qui-ahts included all of Wickaninnish Island, all of Indian Island in Tofino Inlet, and four small fishing stations out at Long Beach. The Ahousaht, Kelsemaht, and Manhousaht requests included both Blunden and Bartlett Islands, Kut-cous Point, various lands on Vargas Island, and some land in Mosquito Harbour, “all covered with timber limits [licences],” according to Indian Agent Gus Cox.

If the requested lands had already been assigned as timber licences, the Indigenous people stood little to no chance of acquiring them for additional reserves. An immense amount of land had already passed beyond their reach in this way. Between 1905 and 1909 a rush of timber speculation occurred in British Columbia, with the government granting thousands upon thousands of timber licences. These encompassed vast tracts of land around Kennedy Lake, on Meares and Flores Islands, and throughout Clayoquot Sound, much of it going to Sutton Lumber, anticipating construction of the Mosquito Harbour mill. With this timber-licence land off limits, the Tla-o-qui-aht request for all of Indian Island seemed doomed to fail, as one of William Sutton’s many timber licences covered most of the island. The Tla-o-qui-aht did eventually acquire a small new reserve on Indian Island: “that portion of the island exempt from the Sutton timber license.” Although logging in Clayoquot Sound had scarcely begun at the time of the McKenna–McBride Commission, this system of granting renewable timber licences set the standard for future logging practices, effectively alienating huge swathes of heavily timbered land. The fate of this land became the flashpoint of an international storm of controversy in the late twentieth century.

Land pre-empted, Crown-granted, or purchased by settlers also stood beyond the reach of Nuu-chah-nulth requests. By 1914, such land accounted for almost all of the Esowista Peninsula and the land bordering on Tofino Inlet, large tracts around Kennedy Lake, most of Vargas Island, and numerous islands and scattered parcels of land throughout Clayoquot Sound. Settlers or land speculators holding land had nothing to fear from Indigenous requests for additional reserves; they knew their claim to the land would be considered superior and upheld. So when Chief Joseph requested all of Wickaninnish Island for the Tla-o-qui-aht people, Walter Dawley had absolutely no cause for concern. Dawley had applied to purchase the entire island in March 1912, declaring he would use the land “for agricultural purposes.” He paid a total of $2,145 for the 156-hectare island. The Crown grant (Number 6654) ceding the island to him was registered in Victoria on May 13, 1914, only two days before the McKenna–McBride Commission met with Tla-o-qui-aht leaders and heard Chief Joseph’s request for the island. The commission denied the chief’s request.

Some of the local chiefs indicated, in their testimony to the commission, that they realized their requests for particular parcels of land would prove hopeless. When Chief Billy of Ahousaht recalled some land at Bear River that former Indian agent Harry Guillod had promised to Chief Billy’s father, he commented: “A white man came along, and he is living there now, and I don’t know that I’m going to get that place, because a white is living there now…I don’t think I am going to get that land any more.” He was right.

As west coast Indian agent at the time of the commission hearings, Gus Cox tried his best to help with various requests for land in his testimony to the commission. He supported several, including the Ahousaht applications for both Blunden and Bartlett Islands. He endorsed many statements the Nuu-chah-nulth leaders made to the commission, and he encouraged every action possible to preserve their right to fish, saying, “I think they ought to have the privilege of catching fish at any time of the year for their own use.” He firmly asserted that the responsibility for depletion in fish stocks in Clayoquot Sound lay with the cannery owners, that it had nothing to do with the Indigenous fishery, which never harmed fish stocks. He stressed the futility of officials insisting that coastal peoples should clear the land and grow vegetables, saying the land did not lend itself to this. He also stated, “I think it is absurd that the Indians should not be allowed to cut down the timber on their reserves,” explaining that “the Department won’t allow them to cut down any timber on their reserves without first getting a permit from the Agent and then that permit only covers two or three trees…I think the Indians ought to be allowed as much as they want.”

The hearings of the commission did not last long, just a few hours in each location. The officials stuck to a strict schedule, always needing to move on to the next reserve and the next tribe a day or so later. Questions posed by the commissioners consistently focused on the same matters: they asked about numbers of people, canoes, and gasoline boats on each reserve; they asked about agriculture, about cows, about fish stocks and clam beaches, about hunting and trapping, about firewood supplies, about summer fishing camp sites. They always asked for named beaches and tracts of land to be identified on maps, a process entirely unfamiliar to the chiefs giving testimony; they knew their territories intimately, but not on printed maps.

The dauntingly formal hearings proceeded with sworn testimony heard before government authorities seated behind a table. The chiefs giving testimony faced close questioning, and most had to speak through an interpreter. Discouraged by such an alien process, many potential participants decided not to attend. Some, like Police George of Opitsaht, submitted a letter instead. At Hesquiaht, the day after the Ahousaht hearing, Father Charles Moser noted in his diary the arrival of the commission on board the Tees. “Only few Indians being here word was sent to Home-is for men to come and make suggestions and put in claims in regard to Indian claims for lands. But these did not arrive before 8 PM, which time was too late for a meeting.” Pleased to have officials visiting, Father Charles boarded the Tees and enjoyed a slap-up dinner courtesy of the visitors. “When I left them in the evening Chief Steward Richards gave me a box along with apples, oranges, bananas, grapefruit, nuts, cucumbers and a bottle of cognac.” Of the meeting with Hesquiaht leaders the following day, Father Charles wrote only “it was short.” Mike Hamilton happened to be at Hesquiaht, working to install the new telegraph line, at the same time as the McKenna–McBride Commission hearings. He noted the presence of the visiting officials in his memoirs: “I have no knowledge of who they were and just what they accomplished; not very much by all evidence. Poor Indians!”

The commission’s work in Clayoquot Sound produced few changes, granting only a few new reserves in 1916, not nearly as much land as requested. The Tla-o-qui-aht acquired only 36.5 hectares on Indian Island. The Ahousaht gained Bartlett Island and Kut-cous Point at the south end of Flores Island, and the Kelsemaht acquired an 11-hectare patch on the southeast corner of Vargas Island, an old village site adjacent to the property owned by the Abraham family. Although Indian Agent Cox stated that “it has always been my policy to try and keep the whites and the Indians as far apart as possible, for the sake of both,” at this one corner of Vargas Island they were in close proximity, for a while at least. Elsewhere in Clayoquot Sound, at the time of the commission, most reserves stood some distance from settlers. Nonetheless, Indigenous people felt hemmed in and surrounded, if not directly by settlers, certainly by the alienating force of fisheries restrictions in waters they had once freely used, and by timber licences on land they thought of as theirs. As Chief Joseph put it: “[The land] is all taken up by white settlers who surround the reserve all round, and pretty soon there will be no room.” Possibly more than any other Nuu-chah-nulth leader in Clayoquot Sound, Chief Joseph had reason to hope his requests for extra land might be heeded. For many years he had been held in high regard by settlers, by various employers, by the storekeepers, by the missionaries. And as George Nicholson pointed out in the Daily Colonist, Chief Joseph’s “counsel was of inestimable value to both the department of Indian affairs and provincial police.” None of this helped when he asked for more land for his people.

As the McKenna–McBride Commission concluded its hearings, the Nuu-chah-nulth people struggled to adjust to a social and economic framework that had changed incalculably in only a few decades. Outsiders had assumed control of their lands and waters. The fur seal industry brought them into the cash economy but that source of income dwindled away, and the people now sought seasonal work in canneries and on hop farms, often far from home. The traditional seasonal rhythms of fishing and food gathering were faltering, and many people, particularly the elderly or the sick, now depended on the Indian agent to provide handouts of flour, sugar, and tea for their very survival. On top of all this, the potlatch ban, in effect since 1884, began to be enforced in an entirely new manner, so this traditional means of wealth redistribution, this institutionalized, engrained generosity among the people, no longer worked as it had in the past.

For many years the potlatch ban had little impact, and on the West Coast these traditional giveaway ceremonies and gatherings continued more or less as before. Potlatches had expanded in the late nineteenth century, becoming increasingly lavish as more money and trade goods became available. In British Columbia, the most elaborate potlatches occurred among the Kwakwaka’wakw (Kwakiutl) people in and around what is now Alert Bay. Host families sometimes gave away canoes, motor launches, money, jewellery, furniture, sewing machines, and musical instruments as well as the more traditional potlatch fare—flour, rice, clothing, basins, plates, blankets, and apples. On the west coast of Vancouver Island, potlatches never reached the proportions of Kwakwaka’wakw potlatches, being smaller and less lavish, yet they served many needs in the changing coastal communities, for all concerned. As Chief Maquinna cleverly pointed out to Indian agent Harry Guillod back in 1886, potlatches acted as “an incentive to industry, a great help to the white trade in Victoria.” Local traders like Walter Dawley consistently benefited from them, carrying items for what he noted in his ledgers as “Ind. Trade,” often cheaper goods of lesser quality for potlatching. “Ind. shawls,” as Dawley called them, sold for twenty-five cents in 1899, destined for potlatches; better-quality shawls then fetched one dollar. Crates of soup plates, washbasins, apples; stacks of blankets; and countless bolts of print fabric passed through Dawley’s hands, at a profit, for potlatches.

Stories of wife swapping, prostitution, and drinking tainted reports of some potlatches, as well as tales of European men taking advantage of these events by providing alcohol, abusing women, and spreading venereal disease. Yet despite occasional outbursts from government authorities about the perceived evils of potlatching, and about the dangers of spreading contagious illnesses like tuberculosis or measles at such crowded gatherings, little concerted effort went into enforcing the ban. “The priests and ministers of all denominations condemn the feast,” wrote Father Augustin Brabant, a comment that seems little more than a nod to the authorities. “As for me, I cannot see any harm in it, although I would rather have it abolished,” he added, with evident disinterest. His successor at the Hesquiaht mission, Father Charles Moser, largely shared this indifference. In his diary spanning the first three decades of the twentieth century, containing thundering denunciations of many other Indigenous customs, Father Charles never once condemned the potlatch, though he mentioned it frequently. “Four painted up and feathered Indians invite me to a potlatch to be held on the 10th,” he wrote on February 6, 1906. Being too busy offloading freight from the schooner Allie Alger, he could not attend, “but a dollar was given to me anyhow.”

The generally laissez-faire attitude toward potlatching came to an abrupt end under the stern eye of Duncan Campbell Scott, deputy superintendent of the Department of Indian Affairs from 1913 to 1932. Dismissing the “senseless drumming and dancing” of potlatches, as well as the sun dances and thirst dances of the Prairie First Nations, Scott determined to enforce the federal law against all these practices. He questioned how anyone could sympathize with such traditions, maintaining that “the original spirit has departed, and...they are largely the opportunities for debauchery by low white men.” Repelled by the “prolonged idleness and waste of time, by ill-advised and wanton giving away of property and by immorality,” Scott demanded that Indian agents and police take action against potlatching.

Renowned for his poetry as well as his career as a bureaucrat, Scott often wrote of Indigenous people in highly romantic terms. In his verse, they appear as a noble and doomed people, famously summarized as “a weird and waning race” in his poem “The Onondaga Maiden.” Waning indeed. When Scott ruled the Department of Indian Affairs in Ottawa, the Indigenous population had been diminishing for decades as the twin scourges of tuberculosis and alcohol did their worst. Some schoolchildren growing up in BC during the 1920s and 1930s heard in the classroom that Indigenous people would likely not exist in the future; they were all dying out.

In their book An Iron Hand upon the People, Douglas Cole and Ira Chaikin describe how enforcement of the potlatch ban in Scott’s era led to arrests and even to imprisonment, particularly for the Kwakwaka’wakw people, during the 1920s. The potlatch took a beating, more so in some areas than others, but the tradition survived. Hosts chose hidden locations, and they and their guests became expert at evading the authorities or putting up organized resistance and argument. Among the Nuu-chah-nulth, according to Cole and Chaikin, the practice survived, particularly in out-of-the-way places unfrequented by law enforcement officers. Gordon Gibson attended a number of potlatches at Ahousaht in the 1920s, during the height of the enforcement period, and witnessed the generous and practical gifts—everything from smoked salmon to a dugout canoe—being lavished on guests from as far away as Nootka. In the twelve- by twenty-four-metre longhouse, with walls made of 3.6-metre cedar splits, some ten or twenty families would gather for a few days. “The dirt floor was raked smooth, and a little light came through holes made in the roof for the smoke…Three separate cooking fires were often needed for a big potlatch…Some guests would be sleeping while others were dancing, singing or swapping tales.”

Government opposition to the potlatch gradually fizzled out, and by the end of World War II had all but disappeared. More pressing issues of social justice, education, housing, and resource management came to dominate the agenda for First Nations. The law against the potlatch dropped from the statutes in 1951. As the cultural revival of First Nations became increasingly strong through the ensuing decades, potlatch traditions have been revitalized up and down the coast.

As Tofino grew and began to flourish in the early decades of the twentieth century, as more settlers arrived, as more small enterprises took root, as more newcomers plied the waters of Clayoquot Sound, the connections among the various new arrivals slowly strengthened, and a sense of community grew. During these same decades, local First Nations reached their lowest ebb as tuberculosis and other diseases, including measles, whooping cough, venereal disease, and alcoholism, ran rampant. The people became increasingly disconnected from their former way of life.

In the villages on the west coast, missionaries were eager to exert ever more control in their zeal to Christianize and control the people they called pagans. Increasingly, the attention of the missionaries turned to influencing the children. Schools for Indigenous children arrived gradually in Clayoquot Sound: first a handful of sectarian day schools opened and closed sporadically; then, from the turn of the century onward, residential schools appeared. Of all the disconnections faced by the original inhabitants of the area, this would be the worst of all: the growing disconnection from their own children as one generation after another passed through these schools.