Chapter 13: Separation

By 1914, the province of British Columbia operated sixteen church-run and government-funded residential schools for Indigenous children. Three of these stood on the west coast of Vancouver Island: the Presbyterian school at Alberni, which opened in 1891, and the two residential schools in Clayoquot Sound. A mere 14.5 kilometres separated the Roman Catholic Christie School at Kakawis on Meares Island from the Presbyterian residential school near the village of Maaqtusiis on Flores Island. These schools dominated their surroundings. The Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council’s book Indian Residential Schools explains: “In the past, the largest building…was the house belonging to the head Chief of that community. The comparatively huge residential school buildings implied an importance above and beyond that of any local traditional authority…Residential schools had an overwhelming physical-cum-political presence in Nuu-chah-nulth territory.”

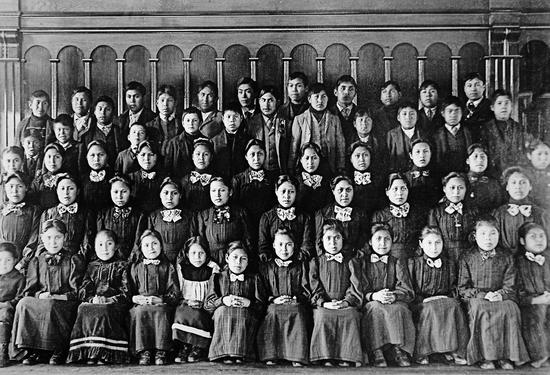

In the many decades of their existence in Clayoquot Sound, the residential schools at Kakawis and Ahousaht housed thousands of children from up and down the coast. During the 1920s and 1930s, attendance at Christie School hovered between 60 and 75 students. The Ahousaht school always had fewer students, averaging in those years 35 to 50, though enrolment peaked at 75 in 1939. That same year, following expansion, student numbers at Christie School increased to 101, giving a joint enrolment at the two schools of 176 children. The Ahousaht residential school closed in 1940, leaving Christie School as the only residential school in Clayoquot Sound from then on. Following World War II, Christie School consistently housed well over 100 students each year, some years more than 120. When Christie School closed in 1971, the school still had over 100 students.

Christie School at Kakawis first opened in 1900 with thirteen children, increasing to twenty-eight within weeks. A group of priests, brothers, and nuns, all members of the Benedictine Order based at Mount Angel, Oregon, formed the original staff at the school, arriving only twelve days before the first students. Many of these Benedictines came from Belgium and Switzerland; they arrived in North America believing they would be working among the Indigenous people near Mount Angel Abbey, never even contemplating the West Coast of Canada. But Bishop Alexander Christie of Victoria arranged with their superiors to have them come to Christie School and so, with English as their second language, absolutely no experience of boats or the sea, and after years of living in supportive religious communities, they arrived. Among them was the school’s first principal, Father Maurus Snyder; also Father Charles Moser, determined to record events in his diary: “In the year of our Lord 1900 on May 16th,” he wrote, “there arrived at Clayoquot on the West Coast of Vancouver Island, BC, Canada the following: Rev P. Maurus, Rev Chas. Moser, The Ven Bros. Leonard and Gabriel, also the Benedictine Sisters Sr M. Placide, Sr M. Frances, and Sr M. Clotilde. We were to take charge of the recently built Christie School.” The school awaited them, freshly painted, still smelling of sawdust, standing high on a south-facing bank overlooking a curving sand beach. Large, imposing, gleaming white, this structure became far larger over the years with various additions and changes. It would stand at the base of Lone Cone for most of the next century.

Father Augustin Brabant had vigorously campaigned for this school since 1895, when he approached Bishop Jean Lemmens in Victoria with the idea. Without a school, Brabant feared his bitter adversaries, the Protestants, would prevail. “Their efforts to invade the coast are very pronounced,” he wrote anxiously. Protestants had been making their presence felt on the coast since the early 1890s, mostly in Barkley Sound and at Nitinat, but by the mid-decade Brabant knew they had infiltrated “his” part of the coast, intending “to give us trouble and pervert our Indian children.” Bishop Lemmens died in 1897, and in 1899 his successor, Bishop Alexander Christie, approved the construction of the Catholic residential school on Meares Island. Brabant selected the site and considered it ideal, because it distanced the children from their own villages and from settlers. The school received a per capita government grant for the education of fifty children. “If we do not accept the grant,” wrote Christie, “it will be given to one of the sects; your children will be perverted and you will lose the fruit of all your labours.”

Although the residential school at Ahousaht opened five years after Christie School, it had been a gleam in the eye of the Presbyterians ever since 1896, when missionary John Russell first arrived there and opened a day school in the village. In 1901 he applied to the Department of Indian Affairs for the bigger prize. He wanted a residential school because only then, in his estimation, could he exert the control he desired. By removing the children from the influences of their home life, he could more readily convert them to Christianity, turn them from their “pagan” ways, and ensure they spoke only English. Russell argued that although over sixty children “received instruction” at the Ahousaht day school in 1901–2, the average attendance had been only twelve per day, a number that had dropped from previous years. He attributed this “to the wandering of the parents for fishing and hunting purposes. As the sealing industry decreases they go in larger numbers to the Fraser River Salmon fisheries and to the hop fields in Washington and can take more of their children with them…This can only be avoided by the erection of a Boarding School.” Faced with the Roman Catholics operating their government-funded residential school at nearby Kakawis, Russell believed the Presbyterians deserved an equal opportunity. Indian agent Harry Guillod supported this notion, pointing out in a letter to his superiors in Victoria in 1902 that Ahousaht had fifty-five school-age children, with forty-one enrolled in the day school. According to Guillod, this provided inadequate exposure to English, for “the rest of the day they are speaking their own language and conforming to the Indian irregular and improvident mode of life.”

The presence of these Presbyterians at Ahousaht enraged Father Brabant. In his early days, Brabant counted Ahousaht territory as Roman Catholic, having baptized 135 children there on one day during his first visit to the coast in April 1874. Yet over the years Ahousaht presented many challenges to the Catholics, no priest ever lived there for an extended period as they did at the Hesquiaht and Opitsaht missions. Brabant built a small Catholic church at Maaqtusiis in 1881, and in 1885 Fred Thornberg helped construct a priest’s residence for Father Jean Lemmens, who remained only two years before becoming bishop of Victoria. Father Heynen succeeded Lemmens there, and like his predecessor he briefly attempted to run a Catholic day school at Ahousaht, reporting to the Indian agent in 1889, probably with some exaggeration, that he had twenty-seven pupils. Statistics for all day school enrolments tend to be sketchy and unreliable, frequently exceeding the estimated number of children living nearby, and often failing to report actual attendance. Father Heynen’s school petered out after a couple of years, like most other sectarian day schools on the west coast. Heynen’s name appears on the 1891 census for Ahousaht, but by then he likely lived there only part time—Father Brabant, who definitely did not live at Ahousaht, also appears as a resident in that census. Father Van Nevel served there on and off in the 1890s, but according to Brabant, Van Nevel neglected Ahousaht in favour of Opitsaht. In 1896 the Presbyterians seized their chance and moved in, setting up both a mission and a day school at Ahousaht. By 1900, when Father Maurus Snyder tried to recruit children from Ahousaht for the newly opened Christie School, he noted that “a burly fellow wanted to shoot me for going on the Ahousat reserve for children.”

Such territorial disputes occurred repeatedly between Catholics and Protestants in many locations on the west coast. At Nootka, around the turn of the century, Father Brabant waged a vigorous battle against the “preachers,” who in turn, according to Nootka storekeeper William Netherby, seemed ready to “fight the priests…and make it hot for the Catholics.” At Clayoquot, the Methodist medical missionary Dr. P.W. Rolston arrived to work among the Tla-o-qui-aht in 1898, followed by Dr. Charles Service until 1902, then by William Stone, Dr. McKinley, and later by Dr. Melbourne Raynor, who established a small hospital on Stockham Island, which the Methodists had purchased from Stockham and Dawley for this purpose after the storekeepers left the island in 1902.

From his established mission at Opitsaht, Father Charles Moser grimly observed these Methodists making incursions into the village he considered his own. In 1901 a Methodist day school opened at Opitsaht in direct competition to the Catholic one; in 1905 the Methodists purchased property near the village and began conducting church services in a house there. The tension continued for years. On November 8, 1909, Father Charles resorted to bribery. “From the beginning of October until today I had empty school days. Nobody would come, they all went to the Methodist school. On All Saints day I offered an Indian 25 cents each day whenever three of his five very near relatives would come to my school. In spite of this offer I had none of them till today and then only one of the five.” A month later, Dr. Raynor staged a potlatch to attract local people to his church. “His church bell rang three times for the meeting,” wrote Father Charles. “About 20 men attended. They were treated with coffee, bread, crackers, pies and fresh pears which latter were furnished by John Grice of Tofino who…exhorted the Indians to join the Doctor in school and church and for so doing were promised free medicine when sick and the best kind of medicine.” Providing medical care, often with government-supplied medicines, played a central role in the work of all missionaries on the coast.

At Ahousaht, where both Catholics and Protestants had set up shop, the local community had no hesitation playing one against the other. In June 1904, as soon as the Presbyterians established a residential school there, a group of Ahousaht leaders protested the actions of the newly arrived Presbyterian teachers in a petition sent to Ottawa. Addressed to Clifford Sifton, Superintendent General of Indian Affairs, and signed by “Chief Billy, Chief Moquiney, Chief Benson, Chief Atlin and Chief Nokhamas [Nokamis],” it stated: “A number of the Indians were frightened and compelled to sign a paper and give up these children to this new [Presbyterian] teachers, and for them to have control of the children until they are 16 years of age.” The letter also pointed out that “the church-house belonging to our old teacher the Priest was standing here on our land, and they could see it alright, so why did they come here to make trouble.” Along with several other petitions from the local community during the early years of the Ahousaht residential school, this document clearly states that parents did not wish their children to attend the school. It also seems to favour the Catholics over the Protestants, declaring of the Catholics that “it was all right with them we had respect for them. They made us better people. We kept from work and trade of a Sunday. There was less whisky and gambling.” In the same letter, the chiefs also wrote: “We know how 2 of the [Presbyterian teachers] assaulted an old white man here and took his children by force from him and why because their mother [an] Ahouset Indian was a Catholic and so was the children. We don’t want such trouble here, we did not ask for these new people to come here.”

This “old white man” was Fred Thornberg, formerly the trader at Clayoquot. Often in the thick of village disputes, Thornberg suspected everyone around him of ill-will and conspiracy; he even believed his water barrels and door handles had been tainted with tubercular blood by the people he called the “Divels of Ahouset Indians.” Although he had married an Ahousaht woman, Thornberg managed to be at odds with almost everyone in the village. He wrote voluminous and angry letters to the priests, to government agencies, even to the Victoria newspaper, complaining about countless perceived wrongs in Ahousaht. A number of his letters detail his fury with the Presbyterian missionaries, accusing them of turning his daughter Hilda against him, and forcing her and his younger son to attend their school. In the long run, little Freddy Thornberg attended the Roman Catholic Christie School like his older brothers. Daughter Hilda, after many dramatic arguments and a volley of letter writing from her father, endured a brief period at the Ahousaht school and then refused to go to school at all.

Despite his contrarian ways, or perhaps because of them, Thornberg fit in fairly well at Ahousaht. The village seemed to thrive on confrontation, and disputes continually flared up, for the Ahousahts never hesitated to challenge anyone trying to impose authority upon them. Back in the late 1880s, Father Jean Lemmens remarked on how his Ahousaht converts would argue hotly during Mass, disputing the homily “with all the noise they could make.” Indian agents, missionaries, storekeepers, and sealing captains had known for many years to expect challenges at Ahousaht. A.W. Neill, the Indian agent who succeeded Harry Guillod, described the Ahousahts as “the most impudent and aggressive on the coast.”

In the heyday of sealing, Captain Sieward wrote to Walter Dawley expressing concern about doing business at Ahousaht. “Billy is here and wants me but I am afraid that…there will be a hot time in Ahousat.” The “Billy” in question was most likely Billy August. One of the most vocal leaders of his time, Billy August figured in many Ahousaht disputes, never afraid to stand up for himself and his people. In the teeth of shrill protests from Fred Thornberg, Billy August set up a small store on the Ahousaht reserve in 1899. Thornberg jealously reported to Dawley that Billy was selling overalls (ninety cents a pair), neckties (twenty-five cents each), and sacks of onions. “I askt him how much he had clearet on his trade he said $20.00 August can read & write and I supose he has lerned from Mr Russell how to write & order goods.” Billy August had his own store letterhead printed and ran his store for a number of years, despite Walter Dawley repeatedly badgering wholesale suppliers in Victoria to stop selling him goods. “Sales to Billy August will cease,” declared Johnson Brothers Dry Goods in 1909, and the Hudson’s Bay Company also agreed to stop trading with Billy August. Yet his little store kept going.

Being literate, August retaliated by sending his complaints about Dawley’s store at Ahousaht directly to Ottawa, going over the head of the local Indian agent. “Dear Sir,” he wrote to Clifford Sifton in June 1904. “We have found out that you are boss of all the Indians, so we ask you for justice.” His complaint focused on Dawley owing rent to the Ahousahts for having his store on their land. “Please have the whiteman’s store removed,” he wrote. The controversy about stores at Ahousaht, and who had the right to be there, provoked agitated streams of correspondence for several years. Meanwhile, both stores stayed put, and Billy August continued to lodge his protests about a number of other issues. In 1911 he complained to Indian Agent Neill that a survey party, hired by the Gibson family, had damaged Indian houses on Ahousaht land at Moyeha, and he asked for reparation. Later, in 1914, he appealed to the Department of Indian Affairs in Ottawa when four Ahousaht people, including his wife, “Mrs Bill August,” were threatened with jail and then fined seven dollars each for potlatching. The Ahousaht missionary, John Ross, who had by then taken over from Russell, made the arrests and brought the charges. “Mr Ross is not good teaching for the children,” wrote Billy August angrily. “He is Policeman all over the west coast Indians they know that he is Policeman…Mr Ross always make a lots of trouble.” The Superintendent of Indian Affairs in Victoria, A.W. Vowell, clearly believing Billy August to be the troublemaker, once described him as “an agitator and a mischievous man.”

On occasion, the authorities took the grievances of Ahousaht leaders very seriously, never more so than in 1900, when William Netherby, who had taken over as the Ahousaht storekeeper, found himself facing death threats. The Ahousahts accused him of grave robbing. Constable Spain from Clayoquot and Indian Agent Guillod became embroiled in the fray, understanding, as Spain explained in a letter to the Attorney General, that grave robbing was “about the greatest crime in the eyes of the Indians.” Spain evidently believed Netherby to be guilty, yet when Netherby appeared before the magistrates at Clayoquot, they dismissed the case. The enraged Ahousaht leaders did not have a chance to air their case in court because, delayed by bad weather, they did not arrive at Clayoquot until after Netherby’s hearing. Head Chief Nokamis of Ahousaht protested in a letter to the Attorney General, demanding Netherby’s removal from Ahousaht land and enclosing a petition from the Ahousaht people. Highly anxious about the situation, Constable Spain lent all the support he could to the Ahousaht complaints. Netherby departed from the area, never to return.

Despite such successes in protesting to government authorities, when it came to the Presbyterian residential school at Ahousaht, local opposition and petitions to Ottawa proved futile. Confident his application would be approved, missionary John Russell began taking day school children into his own home, starting a de facto residential school in advance of government approval. By 1903 he had twenty-six boarders living with him, and he soon received the go-ahead to build a school for up to fifty children. His wife’s health broke down under the strain of all the work, and he resigned before the school had been completed, succeeded by John Ross.

Russell’s bid to set up this school did meet at least some opposition in official circles. Martin Benson, clerk of the Schools Branch of the Department of Indian Affairs in Ottawa, spoke against the idea. Benson had protested before within the department about another residential school matter. In 1897 he noted the spread of tuberculosis in residential schools across Canada: “It is scarcely any wonder,” he wrote, “that our Indian pupils who have an hereditary tendency to phthisis [tuberculosis] should develop alarming symptoms of this disease after a short residence in some of our schools, brought on by exposure to draughts in school rooms and sleeping in overcrowded…dormitories.” Years would pass before others publicly protested the fatal flaws in the hygienic arrangements at residential schools.

In a letter to the head of the department dated November 29, 1901, Benson outlined his objections to a residential school at Ahousaht. He explained that such a school appeared unnecessary, listing all the schools on the west coast of Vancouver Island at the time: residential schools at Alberni and Clayoquot (Kakawis), and day schools at Ahousaht, Ucluelet, Opitsaht, Kyuquot, Nitinat, Ohiat, and Dodger Cove; two of these Roman Catholic, four Presbyterian, and one Methodist. According to Benson, the west coast had no need of another residential school. “While a boarding school would ensure constant attendance and quicker progress,” he wrote, “it is a question whether what they can acquire at the day school will not be sufficient for their future needs.” In his view, the children would likely grow up and live as their parents had lived; therefore, he stated, “it seems to me that they will be better fitted to follow these pursuits…when they are young, than after several years residence in a boarding school.” Benson had often seen religious denominations facing off in the mission field, and he knew all too well the “disputes between opposite religious denominations in their endeavours to obtain Government support for their schools.” He wearily pointed out that “whatever concessions are made to the one will be demanded by the other.” In short, he felt the application for an Ahousaht residential school had more to do with local religious factions jostling for position than it had to do with the children’s needs.

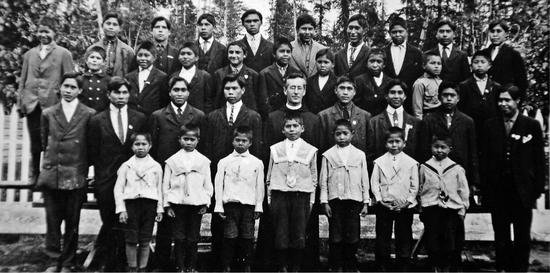

His advice went unheeded. John Ross oversaw the building of the Ahousaht school on a 56.6-hectare tract of land near the Maaqtusiis Reserve. It opened in 1904, with twenty-five students and the first principal, Rev. J.C. Butchart. Within a year of opening, forty children lived at this school, twenty-three boys and seventeen girls. The first school inspection report in November 1905 describes the children as being bright and well, despite an outbreak of whooping cough and an inadequate water supply. Arithmetic and singing receive praise in the report, but the lack of order in the classroom came in for censure.

Christie School responded to the arrival of the Ahousaht school by expanding. Two substantial dormitory wings, added to the original box-like structure in 1904, could now accommodate up to seventy-five students. With staff, support workers, and visitors, this meant the community frequently numbered well over a hundred people. Parents wishing to visit their children could see them in the specially constructed “Indian House” under a strictly controlled timetable allowing no more than a couple of hours on specified Saturdays; parents did not have access to the school or to the dormitories. Visiting parents sometimes came by canoe from Kyuquot, Nootka, or Hesquiaht, as well as from nearby Opitsaht—all the Catholic missions on the coast aggressively recruited schoolchildren from these nominally Catholic villages.

From the outset, Father Brabant warned that “it is terribly hard for the parents to part with their children,” describing a bereft mother to Father Maurus in a letter: “You have no idea of the distress the mother of Mamie is in since the little girl left. I am sure she would do anything to have her back. But it will wear off.” Father Charles’s diary contains several descriptions of distraught parents and crying children being forcibly removed at the time of saying goodbye. One account outlines a miserable scene at Echachis in 1905, when Sister Placida forced little Emma Peter into a canoe bound for the school: “The child don’t want to go and hides under blankets. The parents of course side with the daughter. Sister grabs the child and carries it in spite of howling and kicking like a wild animal down the beach and deposits it in the boat.” Emma Peter’s mother took the unusual and brave step of seeking help from the police constable at Clayoquot to get her child back, to no avail. “The Policeman rightly informed,” wrote Father Charles, “turned against the Indians and sent them home minus Emma who is to stay in school.” Most families did not openly resist in this way; fearing repercussions if they refused, they allowed the children to be taken away to school with stoic acceptance. Nonetheless, the undercurrent of resistance and unhappiness ran very deep, and a familiar pattern emerged: grief-stricken partings, children sometimes hiding or being hidden, police involvement when trouble arose, children forced back to school. Time and again, in subsequent years, police acted as truant officers, seeking out children who had run away from school or whose parents attempted to hide them.

Because of the seasonal work undertaken by most of the parents, often at distant canneries and hop farms, children at the schools could find few people to turn to in their home villages. The villages lay semi-deserted for months at a time during fishing season, when the canneries operated, and when the hop harvests occurred; only old people remained. So if the schoolchildren ran away, their families might not be there. To make matters more difficult, from the earliest days of the schools, many students came from families fractured by disease and death. When recruiting children for Christie School, Father Brabant sought out those he called the “semi-orphans” of tubercular parents, knowing these children, less well-protected by family, would be easier to recruit. All of the children, though, whatever their circumstances, found themselves marooned at the schools, cut off from their own communities, wearing strange clothes, eating strange food, and following stern rules that forbade girls and boys to speak to or play with each other, even their own siblings and cousins. Worst of all, they could not speak their own language, even to each other, and they faced punishment if they did so.

Just over a year after the Ahousaht School opened, serious trouble arose following the death of Will Maquinna, son of hereditary Chief Billy of Ahousaht. Only eight years old, Will was the last of Chief Billy’s children. The others had already died. Will died at the school in November 1906, apparently of food poisoning, following a visit to his grandparents. The school, then with the Rev. J. Millar as principal, insisted he had eaten tainted food while visiting his grandparents and this had caused his death on returning to school. Chief Billy’s outrage and grief could not be appeased. He had been in Victoria when the boy died, and by the time he returned to Ahousaht the body had been buried.

Determined that his complaints be heard, Chief Billy sent a petition to Ottawa, signed by a number of community members, demanding that all the teachers at the school be removed, threatening that no more children from the village would ever attend, and saying parents were removing their children from the school. He met with Indian Agent Neill, who angrily reported to his superiors that Chief Billy had “publicly done his best to injure the school,” dismissing him as “one of the worst Indians on the Coast.” Neill warned the distraught father “in fairly strong terms…he had better take care of how he sets himself to undermine [the school].” Further, Neill insisted that Chief Billy had no right to the title of “Chief,” explaining he had “removed him from being Chief” and instructing others not to use this title in any correspondence with Chief Billy.

Nothing came of Chief Billy’s angry complaints. The Ahousaht school carried on as before, although it learned a lesson from the little boy’s death. Several years earlier, Christie School had learned the same lesson when a boy named Mike, son of the Kyuquot chief Hackla, died at school of pneumonia within months of the school’s opening. Given the outcry that followed these deaths, and the volleys of blame hurled at the school authorities, both schools knew they must try to avoid having children die in their charge. Put simply, if a child became dangerously ill at either school, the administrators preferred to send the child home to die.

On numerous occasions in subsequent decades, sick children were discharged and sent home, encouraging the spread of tuberculosis to the villages. Examples of this abound in surviving records of both Christie and Ahousaht schools. In 1911, John Ross reported from Ahousaht that in a list of sixteen former students, six had died of tuberculosis. In 1912 he wrote that “in the early part of the year two girls were discharged on account of symptoms of decline,” adding that both girls died of consumption at home shortly afterward. From 1904 to 1916, one or two students at the Ahousaht school died each year, the average enrolment being thirty-five. In 1913, three students of Christie School died, “one through tuberculous glands and two through consumption,” according to a letter from Father Frowin Epper to the Department of Indian Affairs. Father Charles Moser frequently described in his diary his travels up and down the coast to attend the deathbeds of former students at home in their villages; he would arrive determined to administer the last rites, remaining by the bedside, whether or not the family wanted him there, until the person died.

A number of letters written by Christie School students to Father Maurus Snyder in 1911 describe their own illness and the illness of other students. “I am sorry to tell you that I am sick yet. Please pray for me,” wrote Maggie Stevens, later sent home. Cosmos Damian William wrote, “I am sorry to say that I am spitting blood for three days.” From Emily Jacob: “I have a sore on my neck both sides.” From Cosmos in another letter: “I am sorry to say that Didac is dead…he lived only four days after he left here.” The sisters also often wrote to Father Maurus, the health of the children dominating their letters. “We lost dear little Barnabas,” reported Sister Mary Clara. “Alice is improving, Maggie…has also bad consumptive cough.”

Treatment of the evidently serious illnesses at Christie School and Ahousaht relied on a limited array of medicines provided by the Indian agent. A surviving “Requisition for Drugs for use of Indians,” dated July 1910, indicates the diseases being treated by the missionary John Ross both at the school and in the village: “Scrofula, Consumption, Rheumatism, Syphilis, Sore eyes etc.” The “drugs” include sulphur and zinc ointment, turpentine, castor oil, Listerine, boracic acid, mustard, iron pills, and carbolated Vaseline. Children who were sick at school appear routinely to have been treated with laxatives and enemas, and in later years with half an aspirin tablet. Each of the schools had an infirmary where children with infectious diseases would be kept, but all too often ailments like influenza or measles proved fatal, in many cases because the children’s health was compromised by underlying tuberculosis or congenital syphilis. The most commonly cited cause of death, whether for children who died at the school or for those who had returned to their villages, was “tubercular meningitis.”

From about 1905 onward, the first wave of children who attended residential school in Clayoquot Sound began returning to their villages to embark on their adult lives. “In 1908 my school days came to an end,” wrote August Murphy, one of the earliest students at Christie School. “I had learned to read and write and speak the English language…Every morning we learned our catechism. Now I went out and started work.” His first job took him to the short-lived marble quarry near Yuquot. “I was the first Indian to work with the mamuthlne [white people] at this work. Later I went with the whaling ships.” In his brief, unpublished memoir, August Murphy noted the many challenges of transition from school. He wrote of how people at home “began using the clothing and food of the white people. Not knowing how to use them the health of the people suffered…The children, it is true, learned the proper preparation of these foods and the way to look after wet clothing, but when we got back to the reserve we didn’t care to force our knowledge on the others. It was the turning point of our civilization.” His memoirs reiterate the appalling death toll of tuberculosis. “One family lost nineteen of twenty children. Another family has only one living of seventeen. Another lost all of eighteen children.” He continued: “Then we learned to make home brew…[and since] the opening of a beer parlour not far from here, many of our boats have been lost and many lives with them.” August Murphy remained a devout Catholic for the rest of his life. His letters to Father Maurus Snyder, along with his brief memoir, are at Mount Angel Abbey. “Remember us in your prayers,” one letter ends.

Apart from their different religious persuasions, the schools at Ahousaht and Kakawis had far more in common than they may have cared to admit. Classes usually took place in the mornings, conducted strictly in English. Religious instruction, chapel, or Bible reading took up part of every day. After 1921, when schooling became compulsory, the schools shared the same basic curriculum for reading, writing, and arithmetic. At one point, the reading included a primer for Grade One entitled Two Little Indians, while the Grade 7s tackled Treasure Island and The Lady of the Lake. Afternoons at the schools meant doing chores: for the girls, housework and cooking and laundry and needlework; for the boys, an unceasing round of chopping firewood, clearing land, maintaining buildings, and gardening. At Christie School the sisters did much of the classroom teaching, and the brothers and priests took charge of practical tasks and taught skills like carpentry and shoemaking. Each school, at different times, taught the boys boatbuilding skills, and each attempted to keep various types of livestock, with immense effort and marginal success.

Some teachers at Ahousaht longed to enter the foreign mission field, arriving at the school for their introduction to missionary work. Usually in their early twenties, with little if any teaching experience, they aspired to go to China or India once they had served time in Clayoquot Sound. Staff turnover was very high. The teachers at Christie School, all Benedictine sisters and fathers and brothers, tended to stay for longer periods, yet they too had been sent to their remote school with little if any idea of what lay before them. From the very beginning they faced shock after shock at Kakawis. On their arrival in May 1900, Chief Joseph of Opitsaht kindly provided a great number of clams for a feast—the horrified sisters had never seen a clam and had no idea how to cook them. The sisters also had trouble getting in and out of canoes, thanks to their heavy woollen habits, and faced serious difficulty in mounting a rope ladder from a canoe to board the coastal steamer. But at least the sisters did not suffer the kind of scrutiny endured by the younger female teachers at Ahousaht. The appearance of any young single woman in the early 1900s always occasioned comment on the coast, with its shifting population of prospectors, surveyors, fishermen, and adventurers. The Ahousaht storekeeper William Netherby once wrote to Thomas Stockham, telling him to come immediately to survey the newly arrived teacher, with a view to matrimony. He assured Stockham that marrying her would cure his rheumatism.

In practical terms, both Christie and Ahousaht schools faced similar challenges; access and transport for each was a logistical nightmare. “Here again is a residential school awkwardly situated for transfer of freight,” wearily commented one of the school inspectors following a visit to Ahousaht. Transporting goods and people gave rise to endless small dramas. Cargoes offloaded from the coastal steamers into freight scows and canoes risked being dumped into the ocean on rough days. To land construction materials, school provisions, and large furnishings required careful timing, reasonable tides, and a good deal of assistance. Landing flour was particularly tricky, for once wetted it could not be used—and huge amounts of flour arrived regularly. A single batch of bread at the Ahousaht school required at least forty kilograms, while Christie School, with its higher enrolment, needed far more. By the late 1950s an estimated 30,000 loaves of bread were baked per year at Christie School; one breakfast disposed of forty-four loaves. Deliveries of up to two tons of flour at a time could arrive at Christie School, requiring every able person to swing into action. Not all of the flour reached shore safely, as Father Charles glumly attested on February 3, 1920 (one of many such comments): “One ton spuds, ½ ton flour...besides a few hundred lbs groceries were received. On landing on the beach our freight boat got swamped in the surf.”

By 1912, nineteen boys and sixteen girls attended the Ahousaht school. That same year Christie School had sixty-six students. Nothing indicates that the two schools ever interacted or visited; they functioned as if the other did not exist. Many students at Christie School came from distant, nominally Catholic, villages up the coast, and faced even greater dislocation from home than the students from nearby Opitsaht. Wherever they were from, all were effectively estranged from their families. At the Ahousat school, most children came from the adjacent village of Maaqtusiis, only a short walk away. Although they saw little of their families, some Ahousaht students were allowed home on Saturdays, but not to stay overnight. On Sundays they all attended church in the village, marching single file along the slippery raised boardwalk; a teacher led the boys first, then the matron followed with the girls, and the rest of the staff trooped along behind. When they reached the village, in order to prevent children slipping off to visit their homes, they walked two by two, closely watched by the staff. In the church, the girls and women of the village sat on one side, boys and men on the other. The schoolchildren occupied the front pews, their family members behind, with mothers and fathers and grandparents craning to glimpse their own children.

Both the Indian agent and the school inspectors made regular visits to all residential schools. The annual reports of the west coast Indian agents follow the activities of Christie School and the Ahousaht school closely in their early years, describing the numbers of children and their health, education, and surroundings. Detailed accounts survive of land being cleared, of the boys learning trades and the girls becoming good housekeepers, learning to sew and cook and excel at “fancy work.” Displays of the fancy needlework from Christie School appeared at the St. Louis World’s Fair of 1904, along with prizewinning samples of the handwriting of the students, who all learned the Palmer method, an immaculate copperplate hand that many students practised for the rest of their lives.

Almost every official report on each school also commented on fire precautions, repeatedly urging improvements, assessing the exits from dormitories, the available ladders, the firefighting water supply and pumps, the students’ training in fire drills. The large wooden buildings, badly heated by inadequate wood and later coal stoves, posed serious fire hazards. At the Ahousaht school, the practice of locking the children into the dormitories at night, presumably to prevent their running away, put them even more at risk from fire. In response to a query from Ottawa in 1913 about how the children could exit locked dormitories in the event of fire, John Ross explained that inside each dormitory “a duplicate key is kept in a…box with a glass cover.” If the need arose, the glass could be broken and the key used. As for the bars on the dormitory windows, Ross reported that “an iron bar is left in each dormitory to break off wooden bars on windows in order to escape...The bars are not iron but wood, 3/4" x 2" [1.9 x 5 centimetres].” He added that each dormitory had a rope fire escape; this consisted of a single rope extending along the roof.

On May 5, 1917, the Ahousaht residential school burned to the ground, along with several outbuildings. No one suffered injury. Up at Hesquiaht, Father Charles heard the news over the telephone: “I could hear through my phone the roaring of the fire and the crackling of wood.” One month later, Father Charles wrote in his diary of “two more Indian schools having burnt down, the one in Alberni and the other at Sechelt near Vancouver.” In all cases, students set the fires in what John Ross described as an “epidemic of arson.”

Christie School escaped, but only just. In early June, students repeatedly tried to set fires, managing only to damage the roof slightly in one case, but making several attempts, hiding matches and stashing kindling under their beds. “So many times the boys tried to burn the school, but no success,” exclaimed Father Charles in a letter. “The finger of God! Deus etiam providebit.” Far more successful as arsonists, the Ahousaht students destroyed their school, but two of them were caught. John Ross reported two girls confessing that they set the fire “by soaking bundles of rags with coal-oil up in the attic and putting a match to them. They hurried down and sat by the kitchen stove busy at their knitting.” Along with six boys who had set the unsuccessful fires at Christie School, these two girls spent time in the Clayoquot lockup on Stubbs Island before appearing in front of local magistrates. Later they faced further legal proceedings in Victoria. Two of the boys served two years each in reform school in Vancouver; one of the girls spent two years in a penitentiary.

The stormy, confrontational atmosphere prevailing at Christie School before and after the fires of 1917 emerges vividly in Father Charles Moser’s diary and in surviving letters from Father Joseph Schindler, principal at Christie School from 1916 until 1919. They each noted the “rebellious spirit” of the students and “a kind of revolution” breaking out in April 1917, when Father Joseph called the police from Tofino to help control the boys. Threats of prison and reform school did not stop the persistent attempts to run away from the school, the stealing of food and Mass wine, the frequently violent clashes between staff and students. Common punishments, especially for the boys, included clipping their hair and confining them for many days in the photographic darkroom or in a bathroom, with only bread and water. Persistent offenders were confined for up to two weeks in the school jail, a newly created facility housed in the old blacksmith shop near the school.

Father Brabant would have been outraged by this. The older priest had died in 1912, forced by ill health to leave Hesquiaht and to spend his final years in Victoria. Trapped there by his age and infirmities, he fretted helplessly about his missions on the coast and about the school he founded, always yearning to return, fearing everything would fall apart without him. Brabant’s powerful influence lingered for many years in the lives of priests who succeeded him, particularly Father Charles Moser and Father Maurus Snyder. During his years as principal of Christie School from 1900 to 1911, Father Maurus frequently sought advice from Brabant. It arrived in lengthy, often irascible, letters in which Brabant shared in great detail his experience on the west coast, his familiarity with Indigenous families and customs, and his determined ideas about how the school should operate and how the priests should behave. He even warned Father Maurus against fasting too much, and chastised him severely for a risky canoe trip that had endangered the lives of students. Brabant also issued an unequivocal warning about physical punishment. “Be sure to abstain from bodily punishment,” Brabant wrote in a letter dated February 13, 1901. “Indians never resort to it and do not tollerate [sic] it on their children.”

Under Father Maurus, the school seems to have developed much as Brabant would have wished, and children rarely faced corporal punishment. But in 1911, Father Maurus left Kakawis and returned to Mount Angel Abbey. Under his successor, Father Frowin Epper, and the following principal, Father Joseph Schindler, the atmosphere in the school changed. In 1917, Father Charles Moser, happily ensconced at the mission at Hesquiaht, reluctantly obeyed a command from his abbot to leave and go to Kakawis. “It will be a sacrifice on my part to move there,” he wrote to Father Maurus, “as Kakawis as it is at present has no attraction for me.” Once there, he soon discovered physical confrontations with students to be commonplace. Between 1919 and 1922, he unwillingly served as principal, finding the position impossible. “[The boys] shake their fists in my face and try to fight me,” he explained to the Indian agent. At the trial of four boys charged with theft, Father Charles confessed his inability to handle them: “I cannot fight with my light weight and height against several of the boys.” The judge responded that Father Charles had lost control of the students and should be replaced, concluding, “You are not severe enough in your punishments.” The next principal of Christie School, Father Ildephonse Calmus, described by the bishop in Victoria as a strict disciplinarian, had no fear of the older boys, nor of inflicting severe punishments. In 1922 he faced assault charges for severely beating one of the boys; the incident came to the attention of Dr. Dixson in Tofino, who examined the boy’s injuries, and the case against Father Ildephonse was heard by Ted Abraham, then a Justice of the Peace in Tofino. It settled out of court.

The nature of punishments meted out at these residential schools depended on the nature of the principal and staff in charge at any given time, and could vary considerably in severity from one period to another. In 1934, with the Rev. Joseph Jones in charge and sixty-three children enrolled, the Ahousaht school received a glowing report from school inspector Gerald Barry. “The whole atmosphere in this school is in advance of our other BC Indian schools.” He continued, “This is one of the best administered Indian Residential Schools in British Columbia. The children are very happy, a condition I do not find prevailing in all our schools, and they are in the best of health. There is little if any corporal punishment.” Five years later, with the school now under principal A.E. Caldwell, the same school inspector, Gerald Barry, reported that “every member of staff carried a strap” and “children have never learned to work without punishment.” Elsie Robinson, who attended the school in the late 1930s, recalled other forms of punishment: “They were always holding a big stick, ready to hit you if you didn’t obey,” she stated in an interview for the United Church Observer in 2010. She also remembered being struck for speaking her native language, a common cause for punishment at residential schools across the country. Other punishments involved humiliation or hard work or both: “Some supervisors made us use a toothbrush to wash the floors. We were forced to do it…Just to be cruel, I guess.”

One of the students at the Ahousaht residential school in the 1920s, McPherson George, became “a very strong believer in the Christian faith that he received through the teachings of the Ahousaht Residential School,” according to his son Chief Earl Maquinna George. Descended from Chief Billy, Macpherson George acquired his name at the school courtesy of the Presbyterians, who could not pronounce his Native name; many children received new names from residential schools. McPherson George and his future wife, Mabel, both attended the Ahousaht residential school, and in the 1930s their son Earl, born in 1926, went to the same school. His mother died when he was two, and in the summers, with his father away working at canneries, in fish plants, and on seine boats, he and his younger brother, Wilfred, were cared for by the school staff.

“Back in Ahousaht, the summer months became very lonely,” he wrote, “because all that was left in the village site of Maaqtusiis were the elders, who were unable to work in the fish canneries. There were very few of us left; I was one of those when I was young because I didn’t have any place to go at times. There were times that I stayed right at the residential school for the summer months.” From 1938, when he was twelve years old, Earl Maquinna George joined his father, the older children, and other adults and commuted every summer to work in the canneries on Rivers Inlet. McPherson George by then had a nine-metre-long combination gillnet–troller named Native Lass, powered by a single-cylinder Fairbanks “one-lunger” engine. This boat would transport large groups of Ahousaht people up to Rivers Inlet for the summer of fishing or working at the cannery, taking three days to travel up the coast past Kyuquot, rounding Cape Scott on the northern tip of Vancouver Island, and ending up at Good Hope Cannery. In his book Living on the Edge, Earl George recalled some 300 to 400 boats being there when they arrived, all preparing to go fishing when the gun went off, announcing the start of the salmon season. Earl found work in the cannery, overseen by the Chinese boss, for fifteen cents an hour. During his first summer, he netted thirteen dollars.

By the 1930s, both Christie and Ahousaht schools made sporadic attempts to encourage at least some traditional skills, often taught by earlier graduates from the schools. In this way lessons in carving, beadwork, and basket weaving occurred at the schools from time to time. Gerald Barry, in his report of 1939, approved of the “mat-weaving and basket making” at Ahousaht, praising one of the beadwork belts as the highest quality he had ever seen anywhere in British Columbia. It was later exhibited at the Canadian National Exhibition in Toronto. At Ahousaht, Nellie Jacobsen, who had attended the school as a child, taught beadwork, weaving, and other crafts. By way of contrast, Elsie Robinson and the other senior girls also attended an evening class called “Charm,” in which, she said, teachers from the Ladies’ Missionary Society “taught [us] how to dress and how to act. We had table etiquette and sex education.” Ahousaht elder Peter Webster also attended the Ahousaht school around this time. In his book As Far as I Know, he wrote: “My memories of attending the school are not pleasant ones. I entered knowing no English. I found that every time I used my native tongue I was punished…we had to listen, morning and night, to readings from the Bible. We did not understand any of it.”

Following the fire at the Ahousaht residential school in 1917, Presbyterian authorities had not wanted to rebuild, but the Women’s Missionary Society provided the funds to construct a new school. Like so many residential schools across Canada, the building went up hurriedly, relying on second-rate work, shoddily and cheaply done, leading to many problems later on. Within little more than a decade, the place was a mess. In 1929, the newly appointed principal, William R. Wood, wrote to Duncan Campbell Scott of the Department of Indian Affairs, describing how the children had suffered in recent years because of the lack of heating, good water, and acceptable toilet facilities. “Looking back over the record of the School during the past two or three years I find that there have been an unusual number of deaths among pupils and ex-pupils, and unusual number of discharges from the School on account of ill health, and that at the present time the number of pupils, especially of girls, who are normally healthy is startlingly low. I am convinced that they suffer constantly from the lack of elementary conditions of human comfort.” In another letter to A.W. Neill, now sitting as a Member of Parliament in Ottawa, Wood stated, “There is scarcely a machine or a utensil about the place that is not worn out and in need of replacement,” pointing out that students “sleep in dormitories from which the chill of the BC winter is never removed by artificial heat…the water they drink is never ordinarily drinkable…the toilet system exhibits none of the features of ordinary decency, much less comfort.” Wood’s warnings went unheeded. He remained at the school a little over a year, perhaps leaving in despair. Few principals of residential schools dared to raise their voices in this manner; if they did, they risked being removed from their positions and posted to other residential schools, even more isolated and deprived.

In 1936, when nurse Bessie Jean Banfill came to work at Ahousaht, she and the newly arrived younger schoolteachers shared their anxieties about the conditions at the school. Among themselves they discussed “how the government allowed six-year old children to be locked in the dormitory of a School, which had been condemned for years as a fire hazard; how the government officials apparently considered cod-liver oil a cheaper way of maintaining the health of the children than to provide them with decent living conditions.” The mandatory requirement that each child receive a dose of cod liver oil twice a day from November to April appalled the nurse; she thought it “awful stuff.” The children seemed resigned to it. After meals, “each child tipped back his head and opened his mouth…I dropped the allotted, compulsory dose…into those gaping mouths.” When a new arrival at the school, a little boy only four years old, refused to open his mouth, an older boy warned him “You’ll catch it!” but the nurse “did not have the heart to hold him, force it down, or to report to [the principal] who no doubt would have strapped him.”

Nurse Banfill’s book With the Indians of the Pacific presents a thinly fictionalized account of her time at Ahousaht, changing some names of places and people. Inspired to come here by glowing reports of the wonderful work done at far-flung missions among Indigenous people, she arrived full of hope, only to be quickly dismayed. When she and one of the teachers challenged the principal about conditions at the school, he replied, “If I could do what I think right for the Indians I would change the whole set-up here!” He explained defensively that his exaggerated official reports about the success of the school ensured its existence, and his position as principal. “Do you mean to say,” one of them asked, “that if you wrote the truth officials would ask for your resignation, because you disagreed with them?” “Wouldn’t they!” the principal replied, adding, “High-up government officials and church congregations want glowing reports to extract generous contributions. They do not want to hear, or let the public hear, about the other side of the picture.”

Every child had to pass a medical examination to be admitted to residential school. The nurse checked all children for infections, impetigo, venereal sores, colds or coughs, and signs of tuberculosis and other infectious ailments. From the outset, she realized that some very young children at the school showed signs of congenital syphilis, a diagnosis confirmed by the doctor in Tofino, who indicated to her that “practically all the five and six year olds had been venereally infected before they were admitted to the School, and that every home had, or had had, tuberculosis.” The principal of the Ahousaht school made it clear to the new nurse that he did not “adhere strictly to government regulations,” and that he could admit students at his own discretion, regardless of their medical condition. Less than impressed by the medical attention the children had been receiving, Nurse Banfill also discovered a boy in the school suffering from diabetes, one of the symptoms being chronic bedwetting. He had been “whipped, starved, threatened, and given…pills” because of this bedwetting, and the principal had concluded “He is too lazy to get up at night.” When the doctor saw the boy, he again confirmed the nurse’s diagnosis, saying, “An interesting case, because I have never seen an Indian with diabetes. I doubt if he will live to be twenty.” Even though the nurse offered to provide injections of insulin, the doctor decided not to treat the disease, for no one in the boy’s family could give hypodermics when he went home.

Nurse Banfill stayed less than a year at Ahousaht. The place and the work overwhelmed her. She had not expected to be put in charge of health care for the entire village as well as the schoolchildren. She discovered on her arrival that her duties included making daily visits to most houses; during one such visit, a young Ahousaht woman further explained her duties to her: “You know we have to keep our houses clean for daily inspection, and you have to report any signs of whisky or drunkenness on the reservation.” The nurse commented, “I wondered if I was supposed to be a policeman as well as a nurse, and why I had not been informed about this unpleasant task.” She grew increasingly uncomfortable with her role, and angered by the visits of the “white bootlegger,” whose boat often stood offshore, attracting local customers.

In 1939, school inspector Gerald Barry wrote to his superiors in Ottawa that the Indian agent was not satisfied with the Ahousaht school, and it would soon close. Several letters reiterate this theme, with Barry also mentioning that the principal, A.E. Caldwell, carried out his duties with the help of a barbiturate called Luminol. Barry continued to repeat his fears about fire safety in the school, a concern of every inspector since the school had been rebuilt in 1917.

In 1940, before the school could be closed, it once again burned down. It was not rebuilt. From this time on, a series of different day schools served Ahousaht, catering largely to elementary students. Some students from Ahousaht went to the Alberni Residential School, particularly in their high school years. When he visited Ahousaht in 1945, marine biologist Ed Ricketts saw no evidence of a school nor of any missionary activity, commenting only that the place seemed “one of the sad and dirty Indian Villages,” but he missed a good deal on that brief visit. The United Church did continue to operate a day school for Ahousaht children, and in 1955 a new mission-funded day school was built there. In 1962 the provincial government assumed responsibility for the Ahousaht school.

Few indications suggest the settler communities at Clayoquot, Tofino, or Ahousaht ever had much awareness of day-to-day realities at either of the residential schools in Clayoquot Sound. The two schools existed in separate spheres, not far away yet maintaining a clear distance from the growing settlements. At Ahousaht, the emerging white community clustered around the sawmill, store, post office, and steamer landing, just across the inlet from the aboriginal village of Maaqtusiis. The Ahousaht school kept itself as isolated as possible, both from Maaqtusiis and the newer settlement. Christie School remained largely invisible to people living at Clayoquot and Tofino, although once in a while the brass band from Kakawis would perform at special events. Very occasionally both schools would be invited to attend public events, but apart from that, little mingling occurred. Few outsiders saw much of the schools and the students, apart from the doctor, various government visitors, and the police who went in search of truant children and brought them back to school.

In the 1920s, Dorothy Abraham visited Christie School several times, accompanying her husband when he went there in his role as magistrate “to straighten out their difficulties,” as she put it. And the Abrahams sometimes took their visitors to the school after visiting the “Indian ranch” (reserve) at Opitsaht, as part of the local tourist attractions. “Like all children the Indians were unruly at times,” she wrote, “and would make off into the bush with sides of bacon and a dozen or so loaves of bread, and be missing for days at a time…I remember the boys drank all the alcohol out of the specimen bottles (snakes, toads etc) and became very drunk. They were up to every prank.” Tirelessly enthusiastic about everything she saw, Dorothy wrote of “the very good Presbyterian Mission” at Ahousaht, and of Christie School being “splendidly run and up to date with all the latest devices, where Indian boys and girls are trained and educated to a very high standard.”

Mike Hamilton also visited Christie School on his travels up and down the coast. He had become friendly with Father Charles Moser, who helped to rescue him from a serious boating accident in Hesquiaht Harbour in 1917. Years later, the priest again rescued Mike when he fell off the dock in Tofino. Unable to swim and weighed down by his oilskins, Mike found himself hauled out of the water by Father Charles. “Born to be hung, not drowned,” he commented. Always prepared to help out if the school needed him, in the early 1920s Mike would go there to do mechanical repairs and to service the movie projector, allowing the children to enjoy an occasional Charlie Chaplin movie as a special treat. He told visitors to Clayoquot Sound that a visit to the school would be “extremely interesting and educational,” and that the staff would “spare no pains to welcome and entertain any visitors who call.” How often such visits occurred is unclear, as is the nature of the tour visitors received.

Christie Indian Residential School outlived the Ahousaht residential school by more than three decades, continuing to operate at Kakawis until it closed in 1971. By then, residential schools were closing all over Canada, as the emphasis on integrated public education grew. As the years passed following these closures, former students began speaking out publicly about their experiences. Gradually, and then more frequently, accounts of mistreatment, humiliation, and physical and sexual abuse were heard across the country, implicating school after school. Inevitably, people on the west coast began to wonder what really went on at the residential schools that had operated right there, in Clayoquot Sound, for so many decades.

Questions have become more and more pointed as revelations continue from residential schools across the country, of unmarked graves, of untold pain, of the still-unfolding outcome of these residential schools. Their legacy remains all too alive; a century and more after they were founded, their influence continues to resound, to disrupt, and to wound.