Chapter 18: Peacetime

Disembarking from the Princess Maquinna at Clayoquot in June 1945, Ed Ricketts looked around at “a lovely place of green gold hummingbirds, I never saw so many in my life before, and thrushes always singing, and rhododendrons in bloom until you can’t see over them, and white seagulls flying by the black mountains. I can’t think of a prettier or better place to work and rest.” Following “the unpleasantness of wartime travel” up the coast from California, on ships still painted battleship grey, Ricketts based himself at Clayoquot for the following five weeks. A pioneer ecologist and marine biologist, Ricketts came from Monterey, California, where he ran Pacific Biological Laboratories on the street later known as Cannery Row, made famous by his close friend, novelist John Steinbeck, who also lived in Monterey. Ricketts had a profound influence on Steinbeck, encouraging in him a deeper understanding of the human factors causing ecological crises of the time, including the dust bowl of the 1930s, powerfully described in Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath, and the overfishing of sardines off California, a subject central to Steinbeck’s Cannery Row.

Ricketts came to Clayoquot to study marine life, collecting specimens and attempting to map what he termed a “biological picture” in and around Clayoquot Sound. He planned to include his findings in a second edition of his well-known book Between Pacific Tides, a study of Pacific Coast marine life. During the time he and his common-law wife, Toni, spent at Clayoquot, Ricketts recorded his keen observations in his diary, writing of the exciting varieties of marine life, and also providing vivid details of the social life he encountered. The “peppy and drunken country dances at Tofino” came in for comment, as did the fluency of Father Mulvihill, then principal of Christie School, when he spoke the Nuu-chah-nulth language to schoolchildren there, and the unspoken racial protocols. Ricketts noted that “visiting of unauthorized whites at these Indian villages isn’t customary and I believe it’s actually prohibited.”

Ricketts stayed at Clayoquot as a guest of Betty Farmer for most of his time on the west coast, living with Toni in the apartment above the old store. Betty, along with her brother and sister-in-law, Bill and Ruth White, remained happily in charge of the Clayoquot Hotel, store, and post office; the place now had cows, chickens, guinea fowl, and a pig to clear the land. Betty was establishing a remarkable garden, and the hotel had a reputation for serving excellent meals. Bill White served as Clayoquot’s postmaster until he and Ruth moved into Tofino in 1947, when Betty took over as postmistress, holding the position until 1964. In her early years, mail still went out on the Princess Maquinna. When the coastal steamships no longer called, she did three mail runs a week to Tofino in her boat. From there letters went to Ucluelet by car and then by boat to Alberni. During her many years on the island, Betty commanded both respect and admiration, described in an article by Mildred Jeffrey as a “wonderful little character…strong as a man [she] runs boats, a tractor, acts as fisherman-hunter guide…day or night she is on hand ready to serve her hotel guests, visiting fishermen, hunters.” In 1949, Betty’s widowed sister Jo Brydges joined her at Clayoquot, and they operated the place together, both sharing a passion for gardening. Freddy Thornberg of Ahousaht, youngest son of pioneer trader Fred Thornberg, became their faithful jack of all trades, working closely alongside them for many years.

In the decade after Ed Ricketts visited the area, Clayoquot’s beer parlour began to face competition. For a number of years the Tofino Legion arranged a temporary liquor licence once a month to host “The Smoker,” an evening when alcohol was served, but in 1954 a licensed bar finally opened there. In 1955 the Tofino Chamber of Commerce (formerly the Board of Trade) wrote to the provincial Liquor Control Board about the “clear necessity” of a provincial liquor store in Tofino. The wait proved long, for the liquor store did not open in Tofino until the mid-1970s. A beer parlour started up in Ucluelet in the 1950s, and by 1959 the new Maquinna Hotel in Tofino opened, with its own beer parlour and a cocktail lounge. Yet despite this competition, the Clayoquot establishment continued to thrive; in 1954 the hotel expanded, with a room for dancing added, and the beer parlour enlarged.

Famous for her sharp tongue and generous spirit, Betty Farmer kept the tradition of Clayoquot Days alive during her years on Stubbs Island, and she also established an enduring legacy there and elsewhere through her love of gardening. She planted many species of trees, shrubs, and flowers at Clayoquot, but above all, as Ed Ricketts immediately noticed, she planted rhododendrons. In 1963, Mildred Jeffrey reported some 130 varieties of rhododendrons growing on Stubbs Island, the damp and mild climate being ideal for this plant. Many of Betty’s rhodos still bloom around the Tofino area, for she shared plants liberally. Because of her encouragement, Ken Gibson took up growing rhododendrons in Tofino in the 1960s; since then his expansive garden has become widely famed, eventually featuring nearly 1,000 varieties and some 2,500 shrubs. Responsible for officially naming a dark red rhododendron “Clayoquot Warrior,” Ken named another “Brianna,” and all over Vancouver Island a species form (R. praestans) is known as “Dot Gibson,” for his late wife. Renowned among rhododendron growers in western North America, particularly for promoting tender maddenii and broad leaf species, Ken Gibson is one of only a handful of Canadians to receive a silver medal from the American Rhododendron Society. His “rhodo heaven” still blazes with colour every spring, near downtown Tofino.

Long before this, outstanding rhododendrons were growing on the west coast in the garden of the genial Scottish pioneer George Fraser, in Ucluelet. An experienced horticulturalist, Fraser settled there in 1894, gradually establishing his extensive nursery garden that would eventually supply the Empress Hotel in Victoria with plants and flowers. Fraser had worked in many well-known parks and gardens, including the newly created Beacon Hill Park in Victoria, before settling at Ucluelet. Renowned as a botanical hybridizer, his garden became a favourite destination for the fledgling tourist traffic on the west coast. Captain Gillam of the Princess Maquinna often delayed the steamer’s departure from Ucluelet to allow tourists time to visit Fraser’s garden, and on the Princess Norah’s inaugural run in 1929, Governor-General Willingdon and his wife also visited the garden. No one returned to the steamer without flowers, particularly rhododendrons. By the time he died in 1944, Fraser had gained international recognition for his work. He sent pollen of his rhodos to Kew Gardens and to growers in England, America, and New Zealand. Fraser’s hybrids, including the one named after him, R. fraserii, flourish in many countries, and plants from his garden appear in a number of places on the west coast, including Cougar Annie’s garden in Hesquiaht Harbour. Over at Clayoquot, “bright with hummingbirds” in the early summer, many rhododendrons share this coastal lineage.

To the eye of outsider Ed Ricketts in June 1945, despite the brilliance of flowers and birds and the generous welcome he received, Clayoquot at first seemed a bit ramshackle. He noted “lots of tumbledown buildings by the wharf, the remains of a blacksmith shop…signs of the Japanese fishing village still in place,” and he heard how the Princess Maquinna no longer always stopped at Clayoquot; in bad weather, especially in the winter, she sometimes bypassed this former coastal hub completely. But the place surprised Ricketts, the comfortable apartment complete with generator-powered electricity and running water, the delicious meals, the lively life of the hotel bar. He had a keen eye for the unexpected, noting the collection of Burmese art at the hotel, including a giant Buddha, acquired by Betty Farmer’s late husband, who had been a magistrate in Burma; the “fantastic library” with titles on communism, labour unions, socialism, and Russian literature; a young Indigenous girl doing chores, effortlessly singing the Gregorian Kyrie from the Missa de Angelis as she worked around the hotel, then paddling home to Opitsaht in her canoe.

Besides collecting samples of marine life from the beaches on Stubbs Island, Ricketts also explored Round Island and Deadman’s Island, as well as visiting Vargas on Dominion Day 1945. “Walked 3 miles along the trail. I should say through the trail since sometimes we were literally tunneling under the underbrush, and we had to crawl on our bellies.” Built by the long-departed Vargas settlers, the sturdy plank trail across the island, with its footbridge over the marshy interior, had been all but obliterated. Later that evening, Ricketts and Toni enjoyed “a swinging dance, complete with brass band, at the Royal Canadian Airforce base.” Four days later they hitched a ride in a jeep heading down Long Beach, collecting specimens en route to Ucluelet, where they joined an impromptu Independence Day celebration at the seaplane base. “I don’t know where the army gets all its liquor under rationing,” mused Ricketts. Fond of a drink, he often made his own concoctions in his lab on Cannery Row, and he found the west coast decidedly odd concerning alcohol. “On the whole west coast of Vancouver Island a shore line of at least a thousand miles [1,600 kilometres], there are only two liquor stores and three pubs. At the pubs you can only get beer.” At the Clayoquot beer parlour he noted how “on Saturday nights people come in from 30-40 mile [48- to 64-kilometre] boat trips,” and how wartime restrictions allowed patrons to buy only one case of beer to go. But despite these apparent shortages, no one wanting a drink went thirsty. Plenty of homebrew could be found in town, and as Jacqui Hansen realized when she arrived in Tofino in the early 1950s, “there were always bootleggers, someone would get a case in and sell bottles to friends.”

At evening gatherings over a few drinks, Ricketts regaled the Whites, Betty Farmer, and others with stories of Monterey and of John Steinbeck, whose Cannery Row had just been published, to great acclaim. In that novel, Steinbeck based his leading character, “Doc,” on Ed Ricketts, and even 2,400 kilometres away at Clayoquot, the fame of this character dogged Ricketts. Yet later on, recalling his time with them, Ruth White remembered Ricketts not as the larger-than-life “Doc” but as an astute and dedicated collector, able to discern imperceptible creatures in seemingly empty tidal pools. “He would see things in tide pools where I would see nothing,” she stated. “One time he found these little transparent fish and all you could see were two little black dots for the eyes.” Ricketts and Toni collected hundreds of marine specimens during their time at Clayoquot, carefully preserving them in their makeshift lab above the old store. Five weeks after they arrived, after a final party, Ricketts and Toni departed on the Maquinna. Bill White recalled in a letter: “After the Ricketts departure, we all got gloriously drunk...Betty went to milk the cow and passed out, hanging onto its tail.”

A year later, Ricketts and Toni, accompanied by his son Ed Jr., returned to Clayoquot aboard the Princess Norah, as the Maquinna was having her wartime grey painted over. They stayed for a month, roaming the intertidal zones as before, collecting specimens, constantly amazed by the immense variety of species. Describing a reef off Wickaninnish Island, spangled with thousands of starfish of every imaginable colour, Ricketts wrote: “There are more species here, and incomparably more individuals too, than anywhere else in the world.” They headed north to continue collecting in Haida Gwaii and in Alaska, and on their return they saw the destruction caused by the June 23, 1946, earthquake. Measuring 7.3 on the Richter scale, this had been “one of the most severe which has been recorded in Canada within historic times,” according to the Seismological Division of the Dominion Observatory in Ottawa. On Stubbs Island, many chimneys had been knocked down, windows smashed, and most of Betty Farmer’s dishes broken. Ricketts’s sample bottles, with their specimens preserved in alcohol, mostly remained intact.

True to form, Ricketts threw another farewell party when they left on July 20, 1946, this time aboard the Princess Maquinna, attended not only by his Stubbs Island friends but also by Captain MacKinnon, who kept the ship tied up in Tofino for an extra half hour while he continued partying. “Everyone including Capt. MacKinnon got quite swacko,” wrote Ricketts. When the ship finally got underway, the officer on duty, “so young and gold braid and trim and disapproving,” disputed with the captain exactly where they were in the fog that enshrouded the ship once they left Tofino, and about when and where to change course. “And of course it worked as you’d suppose. The drunken Capt., by this time cold sober, was right, and the precise and sober younger office was minutes and a half a mile off. The Capt. was on the nose.”

Ricketts planned a return trip to Clayoquot in the summer of 1948, accompanied by Steinbeck, so the two of them could work on a new book, The Outer Shore. A week before departing, Ricketts’s car collided with a train at a railway crossing in Monterey. Ricketts died a few days later. Bill and Ruth White heard the news on the radio, shocked by the death of the charismatic man they had expected to see within days, who once said his “idea of heaven was to be out on the reef near [Lennard Island] on the west coast at low tide when the sun was rising and marine life was just teeming.”

The teeming life of Clayoquot Sound has attracted countless scientists and researchers both before and since Ricketts’s day. Initially they came as collectors, trying to gather, preserve, mount, and catalogue every specimen they could find, marine life, insects, birds, and mammals, working to establish an inventory of the amazingly rich biodiversity of Clayoquot Sound. Professor George Spencer of the University of BC spent a summer at Tofino in the mid-1920s, boarding with Dorothy Abraham and her husband. He set up a laboratory in a shed where he dissected and bottled his specimens, much to the fascination of his landlady, who greatly enjoyed the “wonderful collection of crabs and every kind of marine life, every bug and beetle that crept upon the earth at Tofino: we all became biologists that summer!” In 1931, as a very young man, Ian McTaggart-Cowan arrived for his first visit to the area, ranging far and wide as he collected small mammals and birds. This work involved shooting and trapping them, then skinning, cleaning, drying, and stuffing the creatures at makeshift field camps. McTaggart-Cowan went on to a distinguished career as a professor at UBC, gaining international recognition for his work as a wildlife biologist and conservationist, and later awarded both the Order of Canada and the Order of BC. He worked with a wide range of environmental organizations over the years, inspiring many scientists and naturalists who followed in his wake, including Charles Guiguet. For two summers in the early 1960s, Guiguet came to Clayoquot working as a field biologist for the National Museum of Canada. A specialist in birds and small mammals, he focused on collecting varieties of mice, becoming known locally as the “mouse man.” His wife, Muriel, and his children accompanied him, camping on Stubbs Island. “We had 5 tents: the boys’ tent, our tent, the girls’ tent, and then a skinning tent,” Muriel recalled in an interview with Briony Penn. “Charles would make up the birds, and skulls had to be dried. So there was a little packet of skulls hanging above the stove.” Like his mentor Ian McTaggart-Cowan, Guiguet visited Cleland Island, enthralled by the many varieties of marine life, birds, and small mammals there. On his recommendation, and with the active involvement in later years of Bristol Foster of the BC Provincial Museum, Cleland Island became the first ecological reserve in BC in 1971.

In postwar Tofino, dances took place every month at the Legion, and twice a month at the Community Hall, with live music provided by Walter Arnet and Sam Craig on violin and piano, and other musicians and dancers often coming up from Ucluelet to join the lively whirl. “We danced polka, schottische, foxtrot, waltzes,” remembered Jacqui Hansen. “Everyone went.” And thanks to Les Busswood, ex-RCAF, now living in Tofino with his wife, “we have a permanent movie in town!” Islay MacLeod wrote excitedly for the West Coast Advocate in January 1946. Delighted that the Busswoods had chosen Tofino as “a home for their movie projector,” she described the first show in the Community Hall, attracting “swarms of ‘first-nighters’” to a Bob Hope movie. Les Busswood’s van, emblazoned with L.D. Busswood, Mobile Movies, Tofino – Ucluelet, travelled the region showing films in community halls, First Nations villages, and logging camps.

The immediate postwar years found Sid Elkington and other storekeepers in Tofino regretting the departure of RCAF personnel from the area. Trade decreased considerably following the bustling days of the war, with so many people coming and going from the air base. Yet though business slowed, Tofino’s population increased slightly, for a number of discharged air force personnel and workers decided to settle there, some building homes right in the town. Many practical improvements also resulted. “Tofino benefited by being connected to the large airport electric power generating plant, with the capacity of supplying power and light for the whole district,” wrote Elkington in his memoirs, relieved he no longer had to maintain and produce his own power from a generator. Two street lights appeared in the town in 1947, provided by Hilmar Wingen; not long afterward, lights appeared on the government wharf, and a long-awaited water system for the village seemed about to become a reality, having been approved by the village council. “Also, the old telegraph service was replaced,” Elkington reported, “with an adequate telephone service, connected to the cities.”

In April 1947, after seventeen years in Tofino, Sid Elkington sold his store to the Kyuquot Trollers’ Co-operative Association. Some Tofino fishermen already belonged to this co-op, for it had a fish-buying camp in town. Now the co-op wanted to add Elkington’s store to its chain of fish camps and stores stretching along the coast from Barkley Sound to Quatsino Sound. Elkington left Tofino and started working for the co-op as purchasing agent and stores manager in Victoria. The Kyuquot Trollers’ Co-operative continued under that name for a few years before becoming the Tofino Consumers Co-op. It remained at its original site at the head of the government dock until 1964, when it moved to a new building up the hill on First Street, now the site of the Co-op Hardware Store. Towler and Mitchell’s store also changed hands after the war, becoming Sinclair and Boyd’s, and later the Tofino Fishing and Trading Co. Even the Tofino Hotel changed hands, in July 1949 becoming the Tofino Lodge under its new owner, Bud Fillies, who installed a soda fountain and a freezer unit, making his café the first on the coast to serve ice cream sodas. “He also plans to cater private parties and banquets with meals served by candle light,” announced the West Coast Advocate. “His wife will operate a beauty parlor in the same building.”

Having expanded the T.H. Wingen Shipyard considerably during the war, Hilmar Wingen continued to build and launch boats. An enthusiastic crowd attended the 1946 launch of the twelve-metre troller Cash-in, built for Mickey Cashin of Bamfield. In April 1948, Hillier Queen skidded down the ways and entered the water, built for George Hillier of Ucluelet in just three months. She was “48 ft [14.6 metres] long, 13 and a half [4 metres] beam, 30 tons. 6 cylinder Murphy Diesel, 135 horsepower. With automatic controls, 75 watt radio telephone, and a ‘Bendix Sounding Unit’ for all types of fishing, first trip being for halibut.” Two tugs and one other troller emerged from the shipyard in 1948–49. In 1950 Wingen built the crab boat Jo-Anne for Pierre Malon and Bill White, along with two other vessels, and 1952 saw the launch of the fourteen-metre tug Dog Star, with its “360 hp Cummings Diesel, first of its kind to be used on a marine installation.” In 1950, “another new progress for Tofino was the opening of the Standard Oil station, operated by H. Wingen. The station is situated near the Tofino Marine Service with a float and wharf for the convenience of all boats.” The whistle marking the beginning and end of the workday at Wingen’s, at 9 a.m. and 5 p.m., continued to sound until 1955, when boat building ceased and the business diversified. The shipbuilding records of the company, dating back to 1918, reveal twenty-seven new vessels built there, including six tugs (two for the Gibson brothers), six boats rebuilt from the waterline up, and six other substantial rebuilds. The Wingens’ various operations over the years had immense influence in Tofino, creating steady employment and serving as a cornerstone of the local economy well into the 1970s.

A new enterprise started up in Tofino shortly after the war, when Pierre Malon and William Lornie built a crab cannery at Armitage Point, where the Malons had bought property. Lornie originally tried to start this cannery at Clayoquot, where he worked for some years, but the idea proved unworkable there. At Armitage Point, Pierre Malon and Bill Bond built the cannery, and within its first year the Tofino Packing Company employed three workers from Opitsaht to pick and can the crab. Bill White moved from Clayoquot into Tofino in 1947 and became Pierre Malon’s partner in the crabbing business. By this time the Malons had moved into their new home near the cannery; Joan (Malon) Nicholson remembered the excitement of seeing her family’s future home, consisting of two sections of the former RCAF hospital, floating down the inlet on a scow toward their property.

A Daily Colonist article by George Nicholson in February 1956 described the cannery, which then operated two boats and offered year-round employment for a dozen men, and part-time work “for the same number of local housewives…and…several salmon fishermen during the off-season.” The business by this stage had expanded, occasionally canning salmon and clams as well as crab; the salmon came from Ben Hellesen’s fish-buying plant in Tofino when he had surplus fish. In the following few years the cannery took on more employees and built larger facilities, as well as extending the dock, still known locally as the “crab dock.” A larger boat, the 11.5-metre Stubbs Island, built in Nova Scotia and designed along the lines of lobster-fishing vessels, arrived on the scene to boost production. Over its years of operation, many employees at the cannery came from Opitsaht, although plenty of Tofino people also found employment there, including many women. The cannery closed in 1964 when Pierre Malon decided to sell the property and move away. Betty Farmer, by that time ready to leave Stubbs Island, bought his property and moved to Armitage Point with her sister, Jo Brydges. With Freddy Thornberg helping, they brought with them many plants from Stubbs Island, digging up a number of their special rhododendrons, some 3.5 metres high. Freddy paddled the plants from Clayoquot to Tofino in his canoe, their foliage trailing through the water. They rinsed them off with a garden hose, and every rhododendron survived.

The aftermath of war saw heated political arguments in many coastal locations in British Columbia about whether the thousands of interned Japanese residents should return to their former lives on the coast. Ed Ricketts wryly noted “a fine political fight going on” in the 1945 federal election: “one candidacy was announced on the bald platform ‘We don’t want the Japs in here—ever.’ ” In the Comox–Alberni constituency encompassing Tofino and Ucluelet, A.W. Neill had served as MP for six consecutive terms, voicing his virulent opposition to Japanese immigration and to the presence of Japanese fishermen in British Columbia since 1921. In 1945, Jack Gibson succeeded Neill as MP, promoting the policy of repatriating all displaced Japanese back to Japan. Many leading citizens of Tofino favoured this policy, clearly stating they did not want any Japanese returning to the village. The first indication of this appears in the minutes of the Tofino Board of Trade in September 1942. At a meeting attended by A.W. Neill, “C.A. Elkington called Attention to the Japanese Question and strongly urged the repatriation of all of Japanese origin.” Three years later, as the war drew to a close, the Tofino Board of Trade sent a telegram to Ottawa, dated December 13, 1945. Signed simply “Tofino Board of Trade,” and addressed to J.L. Gibson MP, House of Commons, Ottawa, it reads: “We wish to again vigorously protest the expected return of persons of Japanese origin to the West Coast and feel we should warn of likely trouble from unanimously determined Canadians against such policy.” A year later, on December 12, 1946, the Board of Trade’s minutes state: “A discussion was held on the Japanese question and it was moved by T.H. Wingen and seconded by H. Sloman that we wire and vigorously protest the return of persons of Japanese origin to the West Coast and feel that a warning of possible danger should be voiced as people in these parts are determined on this matter.”

Early in 1947, the Tofino commissioners, the municipal council of the day, weighed in on the Japanese question. A number of these local officials also belonged to the Tofino Board of Trade, and they expressed in council the sentiments repeatedly voiced by the board. The minutes of January 24, 1947, record a resolution passed by council: “The Commissioners of the Corporation of the Village of Tofino hereby resolve that, at the request of the residents of the Village of Tofino, all orientals be excluded completely from the Municipality, and shall be prevented from owning property and carrying on business directly or indirectly within the Municipality. “ The handwritten minutes add the following information: “Copies of this resolution to be sent to Mowat (MLA) Gibson (MP), Legion and Board of Trade.”

No official motion supporting this resolution appears in the minutes, and no subsequent reference to this subject appears in the ensuing months and years of council minutes. No law or bylaw excluding “Orientals” ever officially passed, nor was any such law or bylaw proposed. Nonetheless, this resolution proved highly effective. No Japanese returned to Tofino after the war. Furthermore, a widely held assumption spread, and continues to be repeated, that a law had indeed been passed banning Japanese from owning property or living and working in the town. The extent of local resistance to their return effectively made any such law unnecessary. It had been passed in spirit, if not in fact. The leaders of Tofino made their point.

Tofino’s attitude toward the returning Japanese reflected similar positions held by communities in Ontario and in the Fraser Valley, where other local councils also attempted to exclude “Orientals.” “Municipal councils actually didn’t have the authority to impose any exclusion of Canadian citizens,” wrote Ken Adachi in The Enemy That Never Was, “but the Department of Labour generally operated on the principle that it would not permit Japanese to reside anywhere in Canada where there was an official protest.”

In 1949, all talk of repatriation to Japan had faded and Japanese Canadians again had the right to vote—a right taken away from them in 1895 and never restored, except to the 222 Japanese Canadian veterans of World War I. Also in 1949, wartime restrictions on the movements of the Japanese ended and they could return to live within the 160-kilometre protected area along the coast. Those who did so risked hostility. In the Skeena district, the Native Brotherhood declared, “We flatly do not want the Japs back in our coastal region,” and many farmers in the Fraser Valley openly resisted Japanese attempts to return. In Ucluelet, some twelve Japanese families did return to live, but not to their former land and homes, which had been absorbed into the adjacent Indian Reserve land. No Japanese returned to Tofino.

Even if he had been welcome in Tofino, Naoichi Karatsu, a Canadian citizen, would not have returned. Like many other families, the Karatsus had left their home intact, believing they would be back, and leaving behind many of their valued possessions, including two precious dolls in glass domes, beloved by the Karatsu girls. The notion of returning withered away in the bitter years of internment. After the war, Naoichi Karatsu took his family to Toronto and started a new life; he never talked about the war years to his children, other than to say he would never return to the coast. Their home in the “Japtown” on Stubbs Island disappeared into the bush like all the others; its contents mysteriously vanishing over time. In August 1948, an article in Island Events by E.M. Watson described a stay on Stubbs Island, and a tour of the island with Betty Farmer. They visited “the now deserted Jap-town” and its “once lovely gardens…completely overgrown.” They peered into one “poor little lost house, now almost completely swallowed up in a jungle of vegetation. The door stood—or rather, leaned—permanently ajar; there were holes in the roof; the windows were gone.” Nothing of any value remained.

During the war years the elderly and respected John Eik faced an impossible task. Surviving correspondence from Mr. H.F. Green, the “Custodian of Enemy Property” in the Secretary of State’s office in Vancouver, indicates that at the request of the custodian, Eik did what he could to safeguard the property left behind in the houses of his Japanese tenants. He made inventories and sold various bits of Japanese fishing gear, stacks of firewood, and other items, submitting monies received to the government agency in charge, to be passed on to the owners. Monitoring the Japanese homes proved very difficult, as the custodian acknowledged in a letter dated November 13, 1944. Alluding to the “general conditions at your end” and the “difficulties you have met with,” Green wrote: “We appreciate that you have done what you can and we would not expect you to be responsible for any losses after the precautions you have taken.” The Japanese homes and possessions fell prey to looting; the houses quietly rotted away or passed into other hands. “People in Tofino had a heyday as soon as the Japanese people left,” Ellen Kimoto commented in an interview in 2012. “They were in there taking absolutely everything.” But this was wartime; no one commented, no one raised awkward questions. A veil of silence fell over the whole subject of Japanese possessions. “I never sold my house in Tofino, but somebody got it,” Johnny Madokoro said, years later. “We never put up a squawk. We thought ‘Oh, the heck with that place, it’s not worth anything.’”

Curious to see where she grew up on Stubbs Island, Ruby (Karatsu) Middeldorp revisited the site of the old Japanese village on several occasions. Members of the Karatsu family from later generations have made the same pilgrimage, noting the bits of broken Japanese pottery and the domestic artifacts marking the area. In the 1980s Rennie Karatsu, Ruby’s older brother, unexpectedly found himself hailed on the street during a visit to Tofino. “Hey, I know you,” said an Indigenous man, who recalled fishing alongside the Karatsu boys. The Karatsus’ eldest daughter, Alice, who had married Tohachiro “Toki” Kondo in 1937, settled in Toronto following the war, where Toki took a series of different jobs, “but his heart remained on the west coast,” according to his granddaughter Christine Kondo. In 1950, Toki began making annual trips out to the coast, fishing every season out of Ucluelet. Because of a recruitment drive by BC Packers, seeking experienced fishermen on the coast, some ten former west coast Japanese fishermen returned to their fishing careers in 1950. Some resettled on the coast, including Mary and Johnny Madokoro and their three boys, who had been living in Toronto. They relocated to Alberni in 1951, and Johnny resumed fishing on his new boat, Challenger II. Mary’s brother Tommy Kimoto and his family settled on a property in Spring Cove at Ucluelet, and Tommy took the helm of the well-known troller La Perouse.

The Tofino municipality’s 1947 resolution to exclude “Orientals” hovered uneasily in the back of many minds for many years. It resurfaced in 1981 when cited by Bob Bossin in Settling Clayoquot, and later came under scrutiny in 1997 when the Tofino council addressed the subject. Councillor Roly Arnet moved to search the records to ensure the resolution was not in effect, and he raised the challenge of issuing an apology to the Japanese. The motion passed, but no apology ensued.

In 1988 the federal government apologized to all Japanese Canadians who had been interned; each surviving internee received $21,000 reparation. In 2012, the BC government issued its own apology to the Japanese. Finally, in 2019, Mayor Josie Osborne apologised to Japanese Canadians on behalf of the people of Tofino for the actions taken against them during the war.

During the postwar years, protracted debates arose in Tofino and Ucluelet about how best to make use of the infrastructure left behind at the air base. One of the earliest suggestions aroused strong local opposition. In 1945, the west coast Indian agent, P.B. Ashbridge, suggested closing the aging Christie School at Kakawis and using the former air force hospital as a new residential school. The school’s principal, Father Mulvihill, petitioned to have the school relocated, and the summer of 1946 saw an intense flurry of letter-writing to authorities in Ottawa. Most writers expressed strong objections to the idea. Jack Gibson, MP, stated that having a residential school near Long Beach “would prejudice the value of the adjoining property for summer resort purposes.” The Alberni District Board of Trade concurred, declaring such a school would “seriously affect Long Beach as a Summer Resort.” Protests also came from Arthur Lovekin and his lawyer. Lovekin, whose property at Long Beach abutted the hospital site, had donated the four hectares of land for the hospital to the RCAF during the war “as a patriotic gesture.” His lawyer stressed that Lovekin had given the land for this specific purpose, and if a residential school were located there his home property and the house, on which “he expended…in excess of $10,000.00,” would suffer “tremendous depreciation.” The lawyer added that other nearby property owners also opposed the school, intimating that if the idea persisted, Lovekin would take legal action to prevent it. Meanwhile, Andrew Paull weighed in from Vancouver. As president of the North American Indian Brotherhood, he stated that Christie School had a legitimate claim to be relocated on government property, that the old school was a fire trap and must be replaced, and that the government should “exert every effort to defeat the rapacious hand of the exploiter.” By the end of August the idea had been quashed, and Father Mulvihill withdrew his application. The Tofino Board of Trade then made another proposal: that the hospital be used as a home for war veterans. Nothing came of that, either, and the land in question reverted to the Lovekins. Fleetingly, the RCAF seaplane base at Ucluelet came under scrutiny as a potential site for relocation of Christie School, but to no avail. The school remained where it was, and the “old fire trap” continued as a school until 1971, later becoming a family treatment centre. In 1983, as long predicted, it finally went up in flames. The RCAF hospital buildings eventually found other quarters; one section still stands at the corner of Campbell and Third Street in Tofino, a long, rectangular structure that once served as a church run by the Shantymen’s Christian Association, and later as Tofino’s maritime museum.

At Kakawis, on Meares Island, the Oblates of Mary Immaculate had been in charge of Christie School since before the war. The founding order, the Benedictines of Mount Angel Abbey, Oregon, had withdrawn from the school in 1938 following many years of internal debate. The responsibility for Christie School had always been an uneasy burden for the Abbey, requiring more administrative effort and support than the abbot in charge felt able to provide. The Benedictine fathers and brothers all returned to Mount Angel, while the Benedictine sisters of Mount Angel remained at the school to assist the Oblates. Under the Oblates, enrolment at Christie School remained consistently around 110 to 120 students. Ever more staff came to work at the school, including, as time passed, a handful of former students who worked as assistant cooks or mechanics, in maintenance jobs, and assisting with sports activities. In the early 1940s, former student Barney Williams agreed to work as the school’s boat builder; with the boys at the school he built a school freight boat in 1941, a new Ave Maria mission launch in 1945, and a motor launch for the Nootka mission in 1947, among other vessels.

In a booklet produced for the Golden Jubilee of the school in 1950, messages of commendation for Christie School appear from many sources. Noel Garrard, then superintendent of the Indian Agency, congratulated all of the staff for how “Christie School has taken a rightful place in the history and progress of the West Coast.” Photographs of the children reveal a total of 122 children attending Grades 1 to 8 that year. Only four appear in the Grade 8 photograph, all of them girls; Grade 1 had a total of forty boys and girls. Photographs of the staff also appear in the booklet, with captions providing their names and positions. These include a brother identified as “Brother Samson OMI, Disciplinarian.” “Disciplinarian” had become a job description. To this day, former students remember Brother Samson as a cruel and unjust man. Many years would pass before the nature of the discipline at this school, and at other residential schools, came under public scrutiny. In the 1950s, few people thought to ask searching questions.

The mid-1950s saw three new Roman Catholic churches under construction in Clayoquot Sound. The large new St. Lawrence’s Church at Ahousaht opened in the summer of 1956, with a 6.7-metre-high steeple. Mr. J. Bonn of Mount Angel did all the interior carpentry, constructing the altar and pews at Kakawis and barging them to Ahousaht. Tofino’s Roman Catholic church, St. Francis of Assisi, opened in 1958, with much of the construction material salvaged from airport buildings. Work also began around that time on the Church of the Immaculate Conception at Hot Springs Cove. Delayed in its construction, the church finally opened in 1963, its opening procession led by Chief Benedict Andrews. At Opitsaht, St. Anselm’s Catholic church had been completely destroyed by a massive fire in June 1925, when flames raced through the village, engulfing twenty-three homes and leaving the church in smoking ruins. Father Charles Moser heard the news up at Nootka, sadly observing, “It was a very hot day with a SE gale.” According to Dorothy Abraham, “the wailing and lamentation could be heard for miles.” Rebuilt by Father Charles in 1927, the church continued to exert considerable influence in the village. At a first communion in May 1958, in a packed church, the West Coast Advocate reported, “All girls wore sheer white nylon dresses, silk veils and orange blossoms, carrying white rosaries…Following mass, a banquet-like breakfast was enjoyed by about seventy-five persons…Harry Charlie of the Opitsats made an interesting speech in his native tongue…there was a procession of the sacrament through the village with the children’s choir singing and reciting.”

Determined to promote the west coast to tourists and visitors, the Tofino Board of Trade decided in 1947 to invite the editor of the Victoria magazine Island Events to Tofino. Board members provided ideas and photographs, and several glowing articles ensued, promising wonderful west coast experiences to visitors. Breathless with hyperbole, most of these articles described raking crabs from tidal pools, fishing in the surf on Long Beach, enjoying nightly beach parties where everyone could “pop corn, steam clams and crabs, roast wieners and tell stories,” with “rousing sing-songs” as part of the fun. Advertisements from many local businesses appeared alongside the articles, offering accommodation at the Tofino Hotel and Café, with “Rates Reasonable. Home Cooking.” The Clayoquot Hotel declared it had a “Homey Atmosphere” and could provide “Fishing. Boating. Hunting,” while the Singing Sands Camp on Long Beach offered daily or long-term accommodation in its cabins: the monthly rate, forty dollars. Situated on Fred Tibbs’s former property at Green Point in the middle of Long Beach, Singing Sands had been offering cabins to rent since 1937. Established by Peg and Dick Whittington, it became an annual retreat for many families; in the postwar years, Gene Aitkens and her two children, Fran and Art, came every year. Gene had first come to Singing Sands during the war to visit her husband, Chas, then posted at the air base, and she became a close friend of Peg Whittington. Fran and her brother delighted in playing on the beach and finding many sizes of glass balls, those translucent fishnet floats from Japan that slipped their nets and floated across the Pacific Ocean to bump gently ashore, sometimes in great numbers, at Long Beach. They also enjoyed seeing guests arrive at Singing Sands. The local bus dropped them some distance away on the beach, and Peg would harness her pony, Duchess, to the resort’s wagon, and drive along the sand to meet them. The children played around the pilings on the beach with Peg’s beloved dog, Posh, and swam fearlessly in the surf. “Art would swim out to get logs, he loved surfing in on them,” Fran recalled.

Peg Whittington remained at Singing Sands for over thirty years, operating her small resort and becoming one of the most respected residents of the area. Her husband died in 1946, a victim of the aftermath of war. A large unexploded mine floated onto the beach near their home, and after the Whittingtons reported it, a naval demolition crew came ashore in a skiff to detonate the mine. Returning to the ship, the small boat flipped in the churning surf. Dick Whittington and the local policeman from Ucluelet courageously tried to save the men in the water, at great danger to themselves. Both Dick and one of the naval men drowned.

As time passed, more accommodation became available at Long Beach. In the late 1930s, only the Whittingtons’ Singing Sands and Hazel and Jim Donahue’s Camp Maquinna had small cabins to rent, but following the war, Nellie and Joe Webb opened the Wickaninnish Lodge at the south end of Long Beach. They moved a section of the RCAF hospital building to the site and transformed it into the main lodge, offering a room with all meals for forty-five dollars per week. Before long they also rented cabins. In the early 1950s, Edgar and Evelyn Buckle arrived in the area with their sons, Neil and Dennis; they built Combers Resort at Long Beach. Shortly after, Jack and Norah Morae built their Long Beach Bungalows, near the Wickaninnish Lodge. Most of these places attracted regular customers who returned year after year: one of the most famous, painter Arthur Lismer of the Group of Seven, came to Wickaninnish Lodge every year from 1951 until 1968, painting daily from his chosen spot, which became known as Lismer’s Beach.

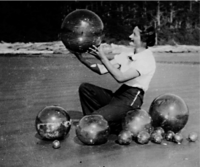

As well as these early resorts, several dozen people built summer cottages, and some thirty permanent homes appeared; by the late 1950s, over sixty residents lived at Long Beach full time. In those years, the now hard-to-find glass fishing floats from Japan floated ashore continually, “a dime a dozen,” according to Neil Buckle. One day in 1956, an unusually large number came in at once; the Buckles collected 236 balls that day in a 2.5-kilometre stretch of beach. Everyone collected the glass balls, competing for the most and the best. Nellie Webb made regular forays along the beach with her Clydesdale horse, Punch, hitched to a wagon, loading up with the balls whenever they drifted in.

A fresh influx of military personnel arrived at the RCAF station at Long Beach in the 1950s, bringing considerable excitement to the area for a few years. At the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, Canada contributed 26,000 men and women to a United Nations force attempting to prevent the communist takeover of Korea. This war intensified the tensions of the Cold War; fears of communism became ever more heightened, along with a growing dread that the Soviet Union might attack North America with long-range bombers and intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). In response, the US and Canadian governments joined forces in the early 1950s to build thirty-nine radar stations, known as the Pinetree Line, along the 50th parallel stretching from Newfoundland to Tofino. Construction on the Tofino station, named C-36 and located on what is now called Radar Hill, began in 1952. Although only a hundred people served at the radar station, the RCAF base at Long Beach reopened to house these personnel, including a number of families. To serve these families and other local children, in 1954 the Tofino Airport School opened in an RCAF building near Schooner Cove, enrolling twenty-six elementary students the first year. High school students took the bus to attend school in Ucluelet, along with their counterparts from Tofino, who had started to make that daily bus trek to high school in 1952.

Although an armistice ended the Korean War in 1953, dividing the Korean peninsula at the 38th parallel into North and South Korea, fear of communist aggression remained intense. The buzz of activity around Radar Hill carried on with the installation of complex radar and communications equipment, and in 1954 the radar station opened, becoming fully operational the following year. At the air base, the presence of military personnel, support staff, and their families created a busy social hub, and it became the scene of frequent dances and other events that often included the townsfolk. Everything from square dancing to bingo and children’s parties took place at the base, and the RCAF baseball team played against teams from local logging camps or the community of Opitsaht. Considerable effort went into these social and sporting events; the 1954 diary of the commanding officer, J.R. Ashworth, states: “More thought being given to future station entertainment—facilities that are most necessary in winter.”

During the height of the Cold War, local boys experienced some of the greatest excitement of their lives when Long Beach became a shooting gallery. Early every morning for about six weeks in 1953, combat exercises and target practice took place there as military aircraft strafed the beach with rockets and machine guns. With the beach closed off to locals, fighter planes roared in, guns blazing. Neil Buckle remembered the screams of the shells flying, heavy thuds of rockets landing, and metre-deep holes left in the beach: “They set up targets on the beach and had a target on Florencia Island in Wreck Bay and Mitchell bombers dropped 500-pound [226-kilogram] bombs on it for weeks on end. They set up cheesecloth targets, about ten feet by ten feet [three by three metres] with a big bulls eye, in front of the sand dunes…The Mustang fighters would start about six in the morning and start strafing the beach…They had so much ammunition that toward the end, they were firing all six rockets at once. As kids we used to collect the .50-caliber brass shell casings.”

In January 1958, Pinetree Station C-36 at Radar Hill closed, made redundant by newer technology and by the building of the Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line in the Arctic, which could provide more lead time in the event of a Soviet attack. The personnel stationed at the RCAF’s Long Beach base departed. Once again, a period of intense military involvement in the area ended, leaving large facilities deserted. Traces of the radar station remain visible on Radar Hill, and near them stands the Kap’yong Memorial honouring Canada’s contribution to the Korean War, in particular noting the battle fought by the 2nd Battalion of the Princess Patricia’s Light Infantry on April 22–26, 1951, a battle that helped stem a major breakthrough by enemy forces. On January 10, 1997, the Pacific Rim National Park Reserve, now encompassing Radar Hill, twinned with the Hallyo Haesang Sea National Park in Korea. Veterans and their families continue to hold a memorial service at the Kap’yong Memorial each Remembrance Day.

The Tofino Airport School continued operating under that name until 1964, when it became the Long Beach School. It carried on serving the growing community in the Long Beach area until its closure in 1970, at which time it had thirty-eight students. During its years of operation, enrolment in this school fluctuated; at its peak in 1956 it had forty-one students, but in other years as few as seven children attended. Meanwhile, in Tofino, enrolment in the village school stood at around forty students per year, remaining at that level through the 1950s.

In this postwar period, Long Beach and Tofino were gradually emerging as two distinct communities, closely linked, but different. Tofino clustered around its fishing industry, commercial activities, and community events, with the Board of Trade and the village council voicing matters of local and regional concern. Long Beach enjoyed a more fluid population made up of visitors, scattered residents, a few resorts, and summer people; also, by the 1950s, a few Tla-o-qui-aht families lived permanently at the traditional Esowista village site. Thanks to the military presence in the area, the road between Ucluelet and Tofino had greatly improved, although its washboard surface and potholes still gave rise to many complaints.

Transportation on the west coast underwent many changes in these years, with ever more small aircraft flying up and down the coast. Commercial air traffic had begun arriving in Tofino in the mid-1930s, with Ginger Coote Airways serving the gold-rush community up the coast at Zeballos in single-engined Fokkers and Fairchilds. These airplanes often stopped in Tofino, becoming famed for their mercy flights, rescuing injured or sick people in remote areas. The Gibson brothers at Ahousaht often flew with the red-haired Ginger Coote in the 1930s, never worrying about safety. As Gordon Gibson put it, “Ginger never flew very high so there was more chance of flying into a fishboat mast or a lighthouse than into a mountain.” But in May 1938 a Ginger Coote Airways flight crashed near the Alberni Canal, killing everyone on board, including George Nicholson’s wife Mary; the wreckage was not located for ten months. At the time, the Nicholsons’ daughter, Bonnie Arnet, worked as the agent for Ginger Coote Airways in Tofino. In 1941, Ginger Coote sold his company, which was soon absorbed into Canadian Airways.

Sid Elkington in Tofino became the local agent for Canadian Airways, and in the early 1940s local air traffic picked up considerably with two gold mines, the Pioneer and Bralorne, in production on the Bear (Bedwell) River. For a brief time, Elkington operated a branch store up the Bear to cater to all the miners, and he also took over the Tofino Hotel to accommodate their comings and goings. Mrs. Harold Arnet, known as Benny, managed it for him, proving highly adept at handling miners who had been “poured off the plane” from Vancouver after spending their days in the big city drinking away their paycheques. Knowing the state the miners could be in, Canadian Airways provided Elkington with “effective medication in pill form to calm heavy hangovers up to Delirium Tremens.” During the war years, Queen Charlotte Airlines (QCA) also began flying into Tofino; all planes landed out in the harbour, and passengers and freight came ashore in small boats operated by the agents. Later, Canadian Airways installed a small float near the government wharf, and de Haviland twin-engined Rapides, Noorduyn Norsemen, and Barkley-Grows began to arrive in the harbour, carrying more passengers. By the late 1940s, QCA dominated the west coast scene, even negotiating a franchise to land planes at the Tofino air base from 1948 onward. By 1952 it flew daily from Vancouver to Tofino, charging twenty-one dollars for the forty-five-minute flight. Pacific Western Airlines bought out QCA in 1955.

The small float planes operated by these various airlines served the larger coastal communities of Ucluelet, Tofino, and Zeballos, but would also put in at lonely outposts and inlets, speedily whisking people and supplies in and out. “Isolation was a thing of the past,” wrote Tofino resident Alder Bloom in his unpublished memoir. “A small float plane could land on the water at any camp and take a passenger to Vancouver in an hour.” Despite the convenience, he mourned previous times. “The glamour days were gone forever,” he stated wistfully, “when the loggers, fishermen, cannery workers, tourists and business men all dressed up in their best clothes for two days of elegance and fine meals, a touch of class that the Maquinna brought to a group of people whose lives were far from glamorous.” Yet even those who dearly loved the Princess Maquinna could see that the ship was showing her age.

For seven years following the war, the Maquinna soldiered on. In 1951, the journalist Cecil Maiden wrote of her: “She has stolen the hearts of the people, for she is not just a part of their history, she has made it.” He described how she “has taken the sons and husbands of the west to fight in two world wars. At times when no fish boat could fight through the wild seas...always around the headland or behind the driving rain, has been the Maquinna—The Maquinna has just gone on going on.” But she could not go on forever. Month by month, the Good Ship’s problems multiplied. “Passengers will never forget the cockroaches which infested Princess Maquinna in her last years, and the co-operative stewards who improvised traps to catch them—a tumbler, with a little water, greased on the inside with butter. The cockroaches climbed into the glasses, drawn by the butter, but couldn’t climb out again.” Passengers arose repeatedly in the night to empty the water tumbler and its victims out the porthole. Much more seriously, repeated mechanical difficulties, particularly involving her old boilers, afflicted the Maquinna. Even worse from the CPR’s viewpoint, the passenger and freight traffic had steadily declined on the west coast route. Nearly 11,000 people travelled on the route in 1939; by 1951 this dwindled to 7,215. Internal memoranda of the CPR and its subsidiary British Columbia Coast Steamships reveal equally woeful data about cargo. Most of the canneries on the west coast of Vancouver Island had closed by 1951 as companies centralized operations in Steveston, at the mouth of the Fraser River. The remaining plants on the coast processed fewer fish than in earlier years, and by 1952 only a few herring-reduction plants operated consistently. From 1942 onward, the west coast route ran at a considerable loss, each year becoming more of a financial liability. In 1945, Ed Ricketts airily commented of the CPR steamers: “I think they got done years back with the idea of making money…They seem to make an attempt to serve the region.” Yet making money did matter, and losing it mattered even more.

By 1952 Princess Maquinna’s boilers could not raise enough steam, and her speed reduced from fourteen knots to nine. The end came even sooner than expected. CPR authorities had planned to withdraw the ship from service following a final sailing on September 18, 1952, but she did not make that trip. “She was already loaded, passengers and mail aboard, and about ready to sail…Captain Carthew…assembled his passengers in the saloon and informed them that she had made her last trip and would sail no more. They would be permitted to stay on board—many had already retired for the night—and be provided with breakfast, but must find their way up coast as best they could.”

Reaction to the news of the Maquinna’s demise came swiftly. “Coast up in Arms at Loss of Service,” declared one newspaper headline. “The whole economy of the West Coast is at stake,” said R. Barr, member of the Tofino Board of Trade. “We are facing an intolerable situation. We must have steamship or highway connections in order to survive.” The CPR had anticipated such reaction, but its memos and reports also reveal keen anticipation that the long-awaited west coast road would soon connect Alberni to Tofino and Ucluelet. As a result, any planning for a post-Maquinna steamship service amounted to stopgap measures designed to continue just until the road came through. The resulting service, provided by the small and ugly Princess of Alberni, followed by the Northland Prince and the Tahsis Prince, did just that. For a number of years these vessels served the coast, carrying ever fewer passengers, never inspiring much enthusiasm in the hearts of west coasters. Increasingly, passengers chose to travel out to Alberni on the Uchuck, which left three times a week from Ucluelet.

When Padre John Leighton heard that the Maquinna faced her end, he wrote to the superintendent of the British Columbia Coast Steamships. “As Vicar of the West Coast for some years I developed a very warm spot in my heart for the dear old Princess Maquinna. I am sorry to see how gravely ill the poor old lady seems to be, but naturally old age is getting her down.” He requested that the bell of the Maquinna go to the Vancouver Mission to Seamen, where Leighton served as chaplain. In April 1953, after the Maquinna had been broken down to become an ore-carrying barge, Captain Carthew presented her bell to the mission. It accompanied Padre Leighton to Tofino when he retired there, and now hangs in Tofino’s Legion Hall. Ivan Clarke of Hot Springs Cove insisted on witnessing the breaking up of the Maquinna, attending as self-appointed chief mourner; he bought her stateroom keys as souvenirs. Stripped down to a shell and renamed Taku, the former Princess Maquinna stoically served as an ore barge for several years before being scrapped for metal.

By 1952, the Tofino hospital, so proudly built by local volunteers, had been serving the area for fifteen years. Now a fifteen-bed, two-storey institution, it employed three nurses and a doctor, providing service for patients from Amphitrite Point to Estevan Point. Patients living farther north went to Port Alice or to the little mission hospital at Esperanza, near Ceepeecee, which had opened in 1937 and was run by the Shantymen’s Christian Association. Having successfully raised funds for a nurses’ residence, the ever-busy Ladies’ Hospital Aid in Tofino continued organizing a seemingly endless procession of “linen showers,” “superfluity sales,” and “silver teas” to fund specific projects and to purchase equipment. By May 12, 1952, the Tofino hospital had admitted a total of 438 patients so far that year. Then disaster struck.

“It happened on a Sunday while many of the Tofino people were at church,” according to an article in a Ladies’ Aid cookbook from 1983. “The fire horn blew and Maidie Hansen went to the church and quietly entered. She walked over to Katie Monks and whispered, ‘The hospital is on fire.’” Katie Monks yelled out loud, ending the service abruptly. “The parson jumped up on the rails, tripped and fell flat on his face. He got up and went to pull the church bell (also used as a fire alarm), but the rope broke.” Everyone raced for the hospital and joined in fighting the fire, including a group of twenty Freemasons visiting from Alberni. The Ucluelet fire brigade careened wildly up the road to assist; some reports say they covered the forty kilometres to Tofino in thirty-five minutes flat. All patients were safely evacuated, and no one was injured. Rescuers managed to save most of the valuable medical equipment and hospital records, and the nurse’s residence escaped harm, but the hospital building did not stand a chance. Grim-faced Tofino residents looked on despairingly as it went up in flames, reduced in under two hours to charred ruins.

With temporary hospital facilities set up in the nurses’ residence and an RCAF hut, moved into Tofino from Long Beach, controversy erupted about whether Tofino or Ucluelet should be the site for a new hospital. According to Walter Guppy, “considerable animosity was displayed” over the ensuing months in a protracted series of meetings and debates about what to do next. Given Ucluelet’s population of around 700 to Tofino’s mere 300, the larger community felt it had a superior claim. However, factoring in the 1,400 Indigenous people in Clayoquot Sound, and the fact that few of them had cars to drive to hospital in Ucluelet, Tofino won the day, but not before the battle between the two communities caused much ill will.

The hospital board sold the old hospital site, had volunteers clear the wreckage, and agreed to a new site on land donated by the Garrard and Monks families. Hospital fundraising once again began in earnest, with the local hospital board required to raise nearly one third of the hospital’s projected cost of over $200,000. Everyone chipped in: some 100 loggers and fishermen each donated $100, and local businesses contributed generously, as did the Advance Logging Company, MacMillan Bloedel, and BC Forest Products. The Ahousaht band donated $2,500 from the sale of timber rights; normally such revenue would have been shared among all members of the band, but the Ahousahts unanimously agreed to donate the funds to the hospital. In Ucluelet, a “rather risqué fashion show” also contributed its profits to the cause, and a dance at the RCAF station raised funds for a hospital incubator. Everything appeared to be going well, when a last-minute crisis arose. With costs escalating, another $23,000 was needed before construction could start, and the organizers had only thirty days to raise it. The hospital board invited the bank manager from Alberni to explain the situation to local residents. At that meeting, the bank manager accepted promissory notes totalling more than the required amount, with many local people putting up their homes, and in some cases their fish boats, as collateral. Construction on the hospital began in April 1953, relying heavily on volunteer assistance. The official opening took place in August 1954, at a ceremony attended by BC Minister of Health Eric Martin; Paul Sam, the first elected chief councillor of Ahousaht, also took his place among the dignitaries. Dr. Howard McDiarmid arrived to start his new job in the hospital less than six months later. The hospital had “17 beds, four bassinettes and a pediatric ward of ten cribs...a surgical operating room and an obstetrical delivery room…and an x-ray machine,” he recalled.

Fundraising continued long after the hospital had been rebuilt. The Tofino nurses put on a large dance at the air base in the summer of 1955 to raise funds; the “Loggers’ Party” of May 1955, sponsored by Knott Brothers Logging, passed the hat and raised eighty-nine dollars. A performance of the “Jerry Gosley Smile Show,” a popular Victoria-based song-and-dance revue, at the airport on September 23, 1955, produced forty-four dollars for the hospital, with Mr. Gosley planning to repeat the show in Tofino and Ucluelet. “Our hospital means so very much to us all,” the West Coast Advocate stated on May 10, 1956. “In addition to serving the villages of Tofino and Ucluelet, RCAF air base and radar stations, Long Beach, Port Albion, Kennedy Lake Logging Company, Knott Bros Logging, C&B Logging and several other logging camps, many Indian villages and staff and pupils of Christie’s Residential School, officers and members have all worked hard to ensure its success.”

Dr. McDiarmid found he had to cover a lot of ground in his new job; his schedule demanded he be in Tofino on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, and in Ucluelet Tuesdays and Thursdays. McDiarmid became actively involved in local events, helping to establish the Long Beach Curling Club, which set up a two-sheet curling rink at one of the old airport hangars. “The curling club went a long way to heal the bitterness that existed after the two towns’ long fight over the location of the hospital,” he wrote. “It drew residents of Tofino and Ucluelet together.” For several years during the mid- to late 1950s, in order to raise funds to operate the curling rink, the club became involved with the Aero Club of BC, helping to organize large scale “fly-ins” to Long Beach and Tofino Airport on the July 1 weekend. This event attracted small planes from flying clubs all over British Columbia and the United States, some from as far away as Texas. In 1958, 110 private aircraft and a chartered DC-6 passenger plane carried more than 500 people to the shindig. The following year, according to the Vancouver Province of June 22, 1959, a total of 138 planes landed, all of them at the airport—“for the first time they were not allowed to land on the beach.” The Toronto Star Weekly hailed this annual fly-in as “one of the gayest events in the Pacific Northwest.” The Long Beach Curling club catered a massive crab feast for the hundreds of people attending; in 1959, volunteers cooked up 1,800 crabs for the crowd, in huge pots over propane stoves on the beach. “We also sponsored a hangar dance, for which we hired a good outside band,” McDiarmid wrote. “The dance featured the longest bar in Canada, stretching the whole length of the hangar. It was staffed by ten bartenders, all volunteer curlers.”

Because the Ministry of Defence had transferred control of the Tofino Airport to the Department of Transport in 1958, commercial and recreational planes now regularly used the runways. Yet with all the improvements in air traffic, the west coast still had no road link to the rest of the island. Following the war, the Tofino and Ucluelet Chambers of Commerce formed a joint committee to advocate energetically for a road connection to Alberni. In July 1949, to publicize how much the two isolated communities wanted a road, a delegation of the committee—Doug Busswood, Robbie McKeand, and Walter Guppy—undertook a three-day hike over the mountains to Alberni. They then proceeded on to Nanaimo by car to attend the Associated Chambers of Commerce of Vancouver Island convention, which passed a resolution urging the provincial government to build a road to the west coast. At that time, though, other coastal communities were also demanding roads, and to make matters more difficult, the provincial government changed the official terminus of the Trans-Canada Highway to Victoria, rather than Tofino, in an attempt to attract federal funds for the Malahat Drive between Nanaimo and Victoria. All of this put the west coast road on the political back burner. Yet again, the campaign for the road stalled.

Even without a road to the rest of the island, optimistic Tofino residents purchased vehicles “really hot off the market,” according to the West Coast Advocate. “Tofino will soon be classed as the city of cars,” the paper enthused in September 1950, going on to list a few: Dr. Monteith owned “a dashing 1949 Chev,” Borden Grant “a striking 1949 Plymouth,” Bert Knott a “streamlined 1950 Chev,” and the Wingens “a 1950 Mercury.”

In 1952, the Social Credit party headed by W.A.C. Bennett took office in Victoria, heralding a twenty-year era of growth in the province, particularly in the resource industries. Forestry companies had long eyed the riches of the west coast of Vancouver Island, and in 1955, in return for logging concessions, BC Forest Products signed an agreement with the government to build the most difficult, westerly section of the west coast road, which involved a good deal of drilling and blasting of a sheer rock face near Kennedy Lake. MacMillan Bloedel would build the eastern section of the road around Sproat Lake, incorporating and connecting already existing logging roads. This included a notorious set of switchbacks, with unimpeded 300-metre drops into the lake below, at either end of a high, narrow, logging road. The Department of Highways, under the leadership of Phil Gaglardi, would build the twenty-kilometre middle section of the road to the coast.

Now that the road seemed a certainty, nervous reaction to the coming change mounted. After all, not everyone favoured the idea. Through all the decades of clamouring for a road, voices of dissent had been raised: “I can only hope that the road never gets through to Long Beach,” wrote a visitor to George Jackson’s Long Beach home back in 1929, “otherwise the place will be cluttered with a lot of millionaires, hot-dog stands and chocolate bar papers.” At a community meeting held at the Legion Hall around 1949 to discuss the matter, half the audience talked about the economic advantages the road would foster while those opposed argued that the town would become a tourist trap. The “pro” side won the debate by a margin of one vote. “Not that the vote counted for anything, but it did reflect the attitudinal changes introduced by ‘in-comers,’ as the returning veterans were called,” commented Ronald MacLeod in his memoirs.

Long-time resident Mary Evans definitely favoured a road to Alberni. “It took a war and the building of an air base to eventually get a halfway decent road [between Tofino and Ucluelet],” she wrote in her unpublished memoir. “Let us hope that we do not have to resort to the same measures in order to get our Tofino–Alberni road.” But others, including Jacqui Hansen, felt anxious. “The Chamber of Commerce really pushed for the road, but we knew what was coming, we knew the tourists were coming and we were real worried.” Many years later, when the road had become a reality and its full impact dawned, Walter Guppy looked back almost sadly on the many years of intense yearning for the road. “We thought of the advantages of being able to drive out without going to the expense of making a three or four day trip of it. We thought of how our property values would increase and of the employment opportunities that would result. We also thought of sharing the natural attractions of the area with others from the ‘outside.’ But we had little inkling of the extent of the development that would take place once the road was actually built.” All that lay ahead.