Chapter 21: The War in the Woods

In the early 1930s, Tofino’s Rowland Brinckman composed a few lines of verse to protest plans to log Cathedral Grove, the stand of old-growth forest alongside the highway east of Port Alberni, near Cameron Lake. Part of the poem reads:

“Pardon me,” he wrote in a postscript, “if I utter a small squawk in defense of one of the loveliest spots I’ve ever been lucky enough to see.”

Appeals in defence of Cathedral Grove date back to 1911, when James Anderson, secretary of the newly formed British Columbia Natural History Society, put forward a proposal to protect the area, supported by the Vancouver Island Development League. A renewed campaign arose in 1929, led by the Associated Boards of Trade of Vancouver Island. Finally, in 1947, the provincial government established the 136-hectare MacMillan Provincial Park to preserve this area of old-growth forest.

The preservation of Cathedral Grove was highly unusual. Throughout the twentieth century, the prevailing attitudes in British Columbia broadly aligned with the stance of provincial politician Phil Gaglardi, who once declared: “Those trees weren’t put [there] by God to be praised, they were put there to be chopped down!” And so most of the old-growth forests and great trees of eastern Vancouver Island fell to axe and saw, and the advent of the chainsaw, which could cut down as many trees in a day as six handloggers, accelerated the pace of logging enormously. The easily accessible valley-bottom timber fell first, with railways carrying logs to the water’s edge, where they could be boomed and towed to sawmills. By the late 1950s, logging trucks had replaced steam locomotives, leaving many mountainsides on Vancouver Island zigzagged with steep gravel roads, as trucks retrieved timber ever higher on mountain slopes. These roads became so steep that some logging trucks carried 1,350-litre tanks of water to cool their brakes as they negotiated the switchbacks on their way down carrying log loads of over 100 tonnes. Exports of wood products and an increased number of pulp and paper mills within the province led to an ever greater demand for new sources of trees.

In 1959, when the road to the west coast opened, forestry giants MacMillan Bloedel (MacBlo) and BC Forest Products thrilled at the prospect of logging huge stretches of untouched old-growth forest. Long before the road, logging had been done in Clayoquot Sound, but only as a relatively minor industry, feeding logs to early sawmills such as those run by Tom Wingen in Grice Bay, John Darville at Calm Bay, the Gibson Brothers at Ahousaht, and the Suttons in Ucluelet. Most of this early logging could not be seen from Tofino, although since the mid-1950s one highly visible logging scar had stared Tofino residents in the face. Fred Knott and his brother John then owned a logging outfit based in Tofino, Knott Brothers Logging; with the agreement of the Tla-o-qui-aht, this company logged the southern face of Lone Cone, directly opposite Tofino, in 1954–55. “It was a terrible scar, they just shaved the side of that mountain, you could see it from everywhere,” Jacqui Hansen recalled. “But it’s all grown over now.” From out at sea, a few more clear-cuts could be spotted, including a large area on Catface Mountain. Ron Dalziel spent the summer of 1964 fishing offshore, and in his memoirs he wrote of the view looking toward land from his boat: “Except for the odd scar, from a fire or a clearcut—such as Catface Mountain that you could pick up from twenty miles out—untouched timber spread out on the hillsides all the way from Kyuquot right down to Tofino.”

When MacBlo and BC Forest Products (BCFP) began logging in earnest on the west coast, they focused on cutting trees in the vicinity of Kennedy Lake and around Ucluelet. Through the agreement they struck with the provincial government in the 1950s to help build the Ucluelet–Tofino road, the two companies had acquired the rights to log a vast amount of land, including all the timber licences once held by the Sutton Lumber and Trading Company, located around Kennedy Lake, Toquart Bay, and Ucluelet, on Meares Island, and in various other locations in Clayoquot Sound. Additionally, in 1955, BCFP was granted a vast area encompassing 101,214 hectares between Port Renfrew and Estevan Point along the west coast of Vancouver Island. The political shenanigans behind the BCFP grant led to one of the biggest scandals in BC’s political history. The provincial minister of Forests, Robert Sommers, earned the distinction of being the first government minister in the British Commonwealth to be jailed; he went to prison for twenty-eight months after his conviction for accepting a bribe to facilitate the awarding of timber licences to BCFP.

For a while, Clayoquot Sound remained comparatively unscathed, even as clear-cuts began to spread far and wide around Ucluelet. By the early 1970s, several small “gyppo” logging outfits operated within the Sound. One logged at Windy Bay on Meares Island, out of sight of Tofino in Fortune Channel; others set up camps in Shelter Inlet and on Flores Island. Hamilton Logging took over from Knott Brothers and operated a camp from Hecate Bay near the mouth of the Cypre River, under contract to MacMillan Bloedel; in 1972, owner Tom Hamilton died in a plane accident when taking off from that operation. Greenwood Logging also operated under licence to MacBlo in Herbert Inlet, Hot Springs Cove, and later Stewardson Inlet, its operations stretching across the peninsula past Cougar Annie’s garden in Hesquiaht Harbour. Even smaller gyppo logging outfits, like Sam Craig and Dave Bond Logging (C&B Logging), operated in the Kennedy Lake area and Stewardson Inlet. Meanwhile, Lowry Logging was cutting on Catface Mountain, and Ray Grumbach had a small operation first at Hot Springs Cove and later in the Bedwell River area. These independent logging operations, including Pacific Logging and Coulson Prescott among others, peaked around 1976, when MacBlo and BCFP began bringing in their own crews, changing the general mood of logging in the Sound. MacBlo built the Cypre Crescent subdivision in Tofino to house some loggers and their families, and the Maquinna Hotel expanded to serve the influx of new workers. While he accommodated certain MacBlo housing developments, Mayor Don McGinnis worked hard to keep Tofino from becoming a company town.

The agreement the forest companies signed with the provincial government when they agreed to help build the road to the coast required them to harvest on a sustainable yield basis, to replant new trees, to replace the ones cut, and to take precautions against fire. However, the agreement did not stipulate how the companies would harvest the trees, and clear-cutting proved the most efficient and economical method. It also proved to be the most visible. As logging roads extended farther and farther and the clear-cuts grew in number, the cutting methods of the forest companies came under increased public scrutiny. Truck logging gave loggers greater access to wilderness areas, but the roads they built also allowed more and more members of the public to view their logging practices. As an increasing number of British Columbians took to the wilderness along logging roads to camp, hike, fish, and recreate, they were appalled by the landscapes of utter devastation left by clear-cuts. Entire mountainsides had been stripped. Trees had been cut to the edge of lakes, leaving shorelines choked with debris. Rivers and streams ran brown with silt and rocks, rendering them unusable for the fish that had once spawned in them. Soil that would have sustained new growth had been washed away, leaving only bare rock, and erosion caused by logging roads had led to landslides that gouged massive scars on hillsides, visible for kilometres.

This was not the wilderness visitors expected to see, and people began to speak out against clear-cut logging. At the same time, the environmental movement gained ever greater momentum following its protests against nuclear testing in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Groups such as US-based Sierra Club, founded in 1892, and Vancouver-based Greenpeace, founded in 1972, eventually joined forces with Friends of Clayoquot Sound and the Western Canada Wilderness Committee to protest the practices of the BC logging industry. Clayoquot Sound’s two leading industries, logging and tourism, soon reached a crossroads and a bitter collision pitting economic prosperity against the preservation of wilderness.

The first major, widely publicized confrontation in Clayoquot Sound between environmentalists and the forest companies occurred in 1984 on Meares Island, directly across the harbour from Tofino. In November 1983 the provincial government gave MacMillan Bloedel permission to log 90 percent of Meares Island, deferring for twenty years the remaining 10 percent. Rumours had been circulating around Tofino for years of MacBlo’s intentions to log the island. Young people gathering at the Gust o’ Wind Arts Centre in the late 1970s anxiously discussed what could be done to stop this, and those discussions led to the creation of Friends of Clayoquot Sound (FOCS). Everyone in town had seen the results of clear-cut logging around Ucluelet, and even if they supported logging elsewhere in Clayoquot Sound, they did not want that kind of devastation happening within sight of Tofino.

At the request of Tofino municipal council, the provincial government established the Meares Island Planning Committee in 1980. Consultations began among concerned citizens, local environmentalists, First Nations, forestry union representatives, the provincial government, and MacBlo to see what could be done to prevent a repetition of the ugly mess left around Ucluelet. “We didn’t want to look out our windows and see a clear-cut on the south side of Meares Island,” commented Whitey Bernard, who served as Tofino’s representative on the committee. “We even flew Premier Bill Bennett and some of his cabinet ministers up from Victoria in a Beaver to let them see Tofino’s ‘viewshed,’ as they called it, and told them how concerned we were.” Over the next three years, the committee tried to reach consensus, suggesting a number of options to preserve Meares Island. One proposal was to log only half the timber; another to log half now and the rest after twenty-five years. “There were a lot of balls in the air at the time,” said Bernard. “Tourism was beginning to take hold, and many people in the community made their living from logging, but I think MacBlo was beginning to realize that if they were going to log Meares Island they were going to have to do it in a totally different way.”

Frustrated at the slow pace of these negotiations, MacBlo walked out of the Meares Island Planning Committee, calling all the options unfeasible and suggesting that it be allowed to log 53 percent of Meares Island over the next thirty-five years, most of it on the north side of the island, out of sight of Tofino. Around the same time, Tofino resident Harry Tieleman decided to take action. A member of FOCS, and owner of the Esso gas station and Happy Harry’s Restaurant in Tofino, Tieleman purchased a hundred shares in MacMillan Bloedel, which allowed him to attend the 1984 annual shareholders’ meeting at the Hyatt Regency Hotel in Vancouver. At that meeting he put forward a motion that MacBlo cease all plans to log Meares Island. Though his motion ended in defeat, Tieleman gained widespread publicity, prompting MacBlo chairman Adam Zimmerman to blurt in frustration in front of a CBC camera: “Who needs tourists? Tourists are a goddamn plague! Tourists are the most polluting thing you can introduce into the environment!” Zimmerman also asserted that logging Meares Island would look like only a minor dose of acne. “Every time he opened his mouth, we gained another 10,000 supporters,” commented Michael Mullin, one of the leading anti-logging activists in Tofino and a founding member of FOCS. A veteran of the riots in Chicago in 1968, and having, as he put it, “cut [his] political teeth in Chile during the Allende period,” Mullin had a keen sense of how protest movements worked. Along with others in FOCS, he knew the vital importance of attracting publicity and media coverage.

To raise awareness of the proposed logging of Meares Island and to emphasize their total opposition to any logging there, FOCS held the Meares Island Easter Festival at the Wickaninnish school gymnasium in Tofino on April 21, 1984, bringing some 600 people together from around the province. The short-lived Tofino Echo reported that “the media was here in full force.” Regional and international musicians and other entertainers performed in front of the tall carving called Weeping Cedar Woman, created for the event by Godfrey Stephens. Representing the guardian spirit of the area, Cedar Woman became a powerful symbol for conservation. At that Easter Festival, Tla-o-qui-aht chief councillor Moses Martin declared Meares Island to be a Tribal Park, a term he coined to assert Tla-o-qui-aht territorial rights over the island.

Fired up by this declaration, FOCS worked with the Tla-o-qui-aht to make a trail on Meares Island from Heelboom (C’is-a-quis) Bay to some of the oldest and biggest trees on the West Coast, one of which measures over nineteen metres in diameter. The “Big Tree” trail let visitors and journalists see close-up the giant trees that would be lost if logging took place. Local residents also set up camp on the site where logging would start, and Tla-o-qui-aht carvers Joe and Carl Martin began carving dugout canoes on the shore of C’is-a-quis Bay, where they also built a cabin. Anti-logging protesters organized a large Meares Island protest rally in Victoria on October 21, 1984, attracting 1,200 people to the Legislative Buildings. At the protest, the Tla-o-qui-aht raised the 8.5-metre-tall welcome figure Haa-hoo-ilth-quin, a carving by Joe David that stands today outside the Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia.

During this period of intense campaigning and publicity seeking, some of the more militant, self-proclaimed eco-warriors began driving spikes into trees on Meares Island, a practice that would destroy chainsaws, cause injury, and impede logging when and if it began. Neither FOCS nor the First Nations condoned tree spiking.

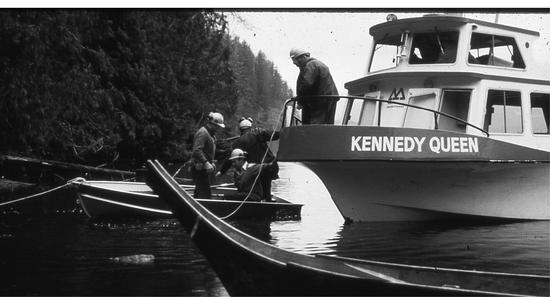

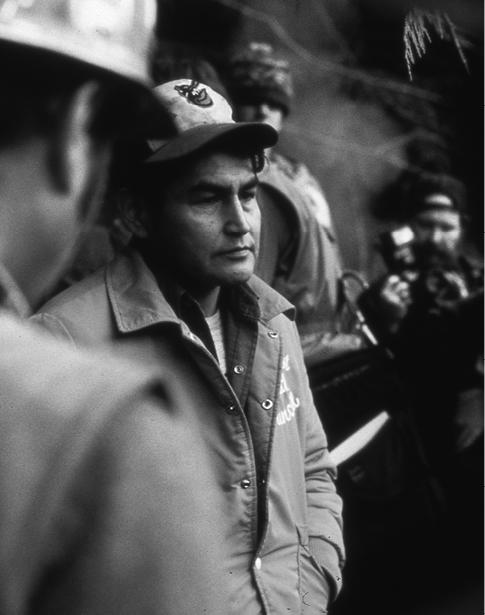

On the morning of November 21, 1984, the MacBlo crew boat Kennedy Queen arrived at Heelboom Bay, with loggers aboard prepared to start operations. A flotilla of boats awaited them, filled with people who had been waiting to be called to the scene when the loggers were en route, to prevent their landing. The organizers radioed the code message “Coffee’s On,” and the boats converged on the bay. Media helicopters flew overhead, and other reporters, who had been alerted to this event well in advance, followed the action from other boats. On the foreshore, sixty or more protestors stood waiting and watching, and a standoff ensued. The RCMP spent several hours trying to negotiate a compromise, and finally, at 1 p.m., the loggers landed. Chief Councillor Moses Martin, waiting on shore, stepped forward to greet them. Taking a paper from his pocket, he began reading the terms of the original timber licence issued to Sutton Lumber and Trading Co. in 1905, the same licence MacMillan Bloedel had acquired in order to log Meares Island. Martin pointed out that the Land Act, in defining the terms of the timber licence, stated: “You will respect all Indian grounds, plots, gardens, Crown and other reserves.” He then said that the land was a Tribal Park and declared, “This land is our garden. If you put down your chainsaws you are welcome ashore, but not one tree will be cut.” Speaking of this historic faceoff in later years, Moses Martin told of an RCMP officer confronting the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council leader George Watts, who stood beside Martin. “He said, ‘I’ve got room to put a thousand Indians in my jail,’...George said, ‘You go ahead. We’ll bring a thousand more.’”

Two days later, MacBlo sought a court injunction against anyone who obstructed their work. The Tla-o-qui-aht and Ahousaht First Nations filed for their own injunction to prevent MacBlo logging their territorial land, occupied by Indigenous people for 4,200 years. They documented the many sites showing Indigenous land use on Meares Island and launched their court case based on aboriginal title. In subsequent years, significant and far-reaching research has documented the history of Indigenous land use throughout Clayoquot Sound, stretching back thousands of years.

In January 1985 the BC Supreme Court ruled MacBlo could go ahead with its logging on Meares Island, a ruling immediately appealed by the Tla-o-qui-aht and Ahousaht. The BC Court of Appeal overthrew the Supreme Court ruling, and on March 27, 1985, the court granted an injunction freezing all plans to log Meares Island until First Nations claims could be resolved. The immediate threat of logging Meares Island had ended. Complex legal proceedings then dragged on for years. Supporters set up the Meares Island Legal Fund, and major fundraising efforts took place, with funds coming from all quarters: high-end art auctions, raffles, dances, and humble bake sales. The Martin brothers of Opitsaht donated two specially carved dugout canoes to be raffled for the fund. As late as 1991, MacBlo continued its efforts to overturn the injunction; the company’s lawyer, John Hunter, told The Sound magazine that summer that the chances of lifting the injunction were good. He was wrong; the injunction held firm.

“The Meares Island confrontation was the first time the whites and natives have gotten together on anything that was worthwhile,” Joe Martin, then a Tla-o-qui-aht band council member, stated in an interview in the New York Times. Reflecting back on events ten years later, local writer Frank Harper agreed, pointing out that “the folks who lived in Clayoquot Sound had probably never before or since been so united around a political issue” as they were on Meares Island. However, Leona Taylor did not sense such a degree of unity in the town: “You had to be pro-logging or anti-logging, there was no room for discussion,” she commented. “It split the town into two factions.” The battle was difficult and sometimes bitter, but Meares Island became a template for future environmental actions and First Nations land claims in British Columbia. It also proved a watershed moment for the people of Tofino.

“The town of Tofino paid dearly for…the Meares Island process,” recalled former mayor Whitey Bernard. “The industry and government weren’t particularly happy that a town had stood up and said ‘We have some very, very serious concerns about logging this particular piece of land.’” According to Steve Lawson in the documentary film Tofino: The Road Stops Here, “MacBlo moved its office to Ucluelet. The Bank of Commerce, some of whose directors also served on the Board of MacMillan Bloedel, became a branch office of the bank in Ucluelet. The Forestry office relocated, the Fisheries and Wildlife Officer left town and the government even threatened to shut down the liquor store.”

“House prices dropped twenty percent and it took a long time for the town to recover,” Bernard noted. “All of this, a direct result of the community standing up to the forestry companies. Thankfully the fish farming industry began and that kept the town going.” Others pointed out that during the years after the Meares Island confrontation, tourism in Tofino began to fill the economic breach, growing slowly but steadily, and attracting many new enterprises to the area.

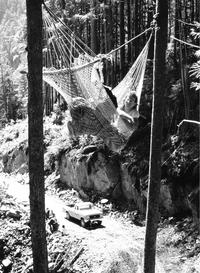

Following their efforts to help the Tla-o-qui-aht prevent logging on Meares Island, environmentalists kept a watchful eye on logging practices elsewhere in Clayoquot Sound. In June 1988, wildlife photographer Adrian Dorst raised the alarm when he spotted workers blasting a logging road in Sulphur Passage on the east side of Obstruction Island, south of Shelter Inlet. This proved to be the work of Fletcher Challenge, the New Zealand-based company that had bought out BC Forest Products in 1987. A small number of protesters descended on the area, first blockading the road builders’ boats, then lying along the route of the proposed road. By law, blasting could not occur with people in close proximity, so the protesters aimed to maintain a presence in the area. Some even suspended themselves in makeshift hammocks from the cliff edges and from trees within the blast safety zone. In one incident during the Sulphur Passage protests, loggers cut down a tree in which a protestor was suspended in his hammock.

Fletcher Challenge responded by applying for a court injunction to prevent the protests. Undeterred, the protesters defied the injunctions and remained in the area, forcing the RCMP to arrest thirty-five of them, among them Ahousaht hereditary chief Earl Maquinna George. Twenty of those arrested received sentences ranging from three to forty-five days. Suzanne Hare was flown to Vancouver in handcuffs, along with local fisherman Pat McLorie, also arrested at Sulphur Passage, to appear before a judge. Their plea of “not guilty” did them little good; some time later Hare again boarded a plane, this time en route to jail with five other women arrested at the protest: Shari Bondy, Valerie Langer, Julie Draper, Bonny Glambeck, and Shelley Milne. Along with five of the men arrested, they chose jail time over paying a fine.

On April 27, 1989, a headline in the Victoria Times Colonist, accompanying a photograph of Suzanne kissing her three children goodbye, read “Mum kisses her children, takes jail for forest fight.” The women had hoped to serve their eight days at a halfway house in Victoria, but instead they went to Oakalla, a maximum-security prison in Burnaby. According to Suzanne, the judge decreed, “If they are going to do time, they are going to do hard time.” On arrival at Oakalla, she recalled how they “were put into a cramped little cell for hours, Shari Bondy was pregnant at the time, and there wasn’t even room to lay down. We were then stripped down, given prison clothes and doused with a chemical delousing poison…until we were finally settled into our cell area.”

These arrests at Sulphur Passage, and the jail sentences meted out, gave a taste of what lay ahead. For Valerie Langer of Friends of Clayoquot Sound, three more arrests would follow in various logging confrontations over the next decade. “After you’ve been arrested once, the other times don’t really matter,” she later commented. “You already have a criminal record from the first time.”

The environmentalists attempted to acquire their own injunction against the road building in Sulphur Passage and requested a six-month moratorium on logging. Chief Earl Maquinna George also sought injunctions to stop the logging on his tribe’s traditional lands. “This was traditional Ahousaht territory and I, as chief, decided to protest the logging,” he wrote in Living on the Edge. In his traditional role as streamkeeper for Shark Creek, a salmon stream in Ahousaht territory draining into the northwest side of Millar Channel near Sulphur Passage, he saw he had a clear duty: “I am the person who watches and sees that no damage is done to Shark Creek.” None of the court actions succeeded in stopping Fletcher Challenge, but the growing publicity created by the activists, using the age-old war slogan “No Pasarán” (they shall not pass), attracted a great deal of media attention. After five months of protests, Fletcher Challenge shelved the Sulphur Passage project and built a road farther back in the mountains, less visible from the water, where it clear-cut the slopes of Shelter Inlet. After the protest, Bob Bossin wrote his song “Sulphur Passage,” which became a rallying cry for protests that followed.

In the early hours of December 23, 1988, the towboat Ocean Services lost its tow, the tanker barge Nestucca, off Grays Harbor, Washington. Attempting to set another line, the boat rammed its barge, causing 5,500 barrels of heavy, thick, bunker oil to spill. Tides and currents soon caused the oil slick to drift northward onto the west coast of Vancouver Island. The residents of Tofino and Clayoquot Sound forgot their differences in responding to this emergency, which threatened local beaches and wildlife. Over Christmas and New Year, groups of volunteers spent every waking hour dressed in white plastic protective suits, patrolling the beaches at each high tide and collecting bag after bag of seaweed clumps, covered in thick tarlike oil. “The oil was several inches deep in huge raised lumps that came in sections up to the size of dining tables,” according to Barry Campbell, then with Parks Canada. “Staff had to remove thousands of dead birds immediately so that predators wouldn’t try to eat them and die themselves.” Local businesses and individuals donated food for a soup kitchen to feed the volunteers; others attempted to save as many birds as they could. An estimated 56,000 birds died. Crab and shellfish beds, as well as herring spawning grounds, suffered from oil contamination. Tofino people focused on the task at hand and kept at it until, finally, the provincial government stepped in to help. Eventually some 5,500 volunteers showed up, some arriving from Vancouver and Victoria to take up the cause and relieve the locals. This incident focused further attention on the fragility of the west coast ecosystem and also demonstrated the unity that still existed in Tofino.

In an attempt to understand more about the environmentalists and to come up with a new approach to “the whole nightmare,” as a company spokesman termed the continuing protests, MacMillan Bloedel hired consultant Rosy Siney in 1989 to assess matters. Her internal report, “The Land Use Controversy: How did we get into this mess?” was to be shared with front-line foresters. In this report, Siney attempted to explain to MacBlo executives how significantly times had changed. Rather than supporting patriarchal/masculine values that saw men conquering the wilderness and felling giant trees as an honourable means of earning a living, society now placed increasing value on matriarchal/feminist ideals relating to “sustainability, conservation, nurturing, caring, slow or no-growth, emphasis on equal opportunity, consensus, [and] choice.” The author pointed out that “the preservationists are attacking not our numbers, but our values.” Stuck in its business-as-usual mentality, MacBlo’s management and, indeed, its individual employees had great difficulty accepting this new reality.

The Sulphur Passage confrontation led to yet more government-appointed committees. These included the Clayoquot Sound Sustainable Development Task Force Steering Committee (CSSDTF), formed in 1989, and its subcommittee, the Clayoquot Sound Sustainable Development Steering Committee (CSSDSC), which grew out of the CSSDTF in 1991, both formed to decide which areas of Clayoquot Sound should be logged and which should be protected. Unsurprisingly, this committee-heavy approach gave rise to frustration. Environmentalists called it the “talk-and-log” period: “While we talked, they logged,” Valerie Langer told Tim Palmer, author of Pacific High: Adventures in the Coast Range from Baja to Alaska. “For fourteen years we tried to protect what was left uncut, and for fourteen years the rate of cutting increased.” Despite the efforts of environmentalists who staged small-scale protests, set up blockades, and sometimes faced arrest, vast clear-cuts continued to spread in Clayoquot Sound and up the coast, many on slopes and watersheds in remote areas unfrequented by tourists and the media, and difficult for protesters to access. Around Hesquiaht Harbour, the sides of Mount Seghers and others stood stark naked; the infamously scalped Escalante watershed north of Hesquiaht could be seen from outer space; and the clear-cuts on the mountainsides above Shelter Inlet, Cypress Bay, and other inlets “look[ed] like they’ve been napalmed,” in the words of protester Betty Krawczyk.

Outraged by the continuing devastation, some activists took matters into their own hands. In April 1991, protesters set fire to the Kennedy River Bridge, putting it out of commission, preventing access to an active MacBlo logging area, and throwing 210 loggers out of work. When MacBlo tried to barge eleven vehicles and their crew up Tofino Inlet to access the area from another direction, the barge sank in Tofino harbour, costing MacBlo huge embarrassment and its insurance company $250,000. “Tofino was a town bewildered this week,” wrote Frank Harper in The Sound, describing “a half-mad, bizarre dance that can only go on at westcoast levels.” In rapid succession the bridge burned, the barge sank, the beloved Legion Hall went up in flames, and the Tla-o-qui-ahts began to boycott Tofino businesses in response to Tofino council’s refusal to support the First Nation’s bid to have land at Tin Wis set aside as an Indian Reserve. Any one of these events would have had the town on edge, but the burning of the bridge particularly shocked everyone. Following a telephone threat that his art gallery would be burned down in retaliation for the bridge destruction, Roy Henry Vickers of the Eagle Aerie Gallery, who had been supportive of the environmental movement, issued a public statement in The Sound. He reiterated his environmental concerns but condemned the burning of the bridge as a criminal act. The town became ever more divided against itself, and the protests continued. Later that year, in September, when the government allowed limited logging in the Bulson Creek watershed, activists blocked the logging road, leading MacBlo once again to seek injunctions, which led to further arrests. Protests and arrests at Bulson Creek continued off and on for years.

A British Columbia-based logging company, International Forest Products or Interfor, entered this tense environment in October 1991. The company had purchased Fletcher Challenge’s tree farm licences when that multinational wound down its operations in the province. Vowing to operate in a different manner, Interfor established an office in Tofino, with Dean Wanless in charge. “Our Chief Forester told me to think ‘outside the box’ and mandated me to practise sustainable forest management; to practise innovative harvesting techniques and to still make a profit,” Wanless said. “It was a tall order and to accomplish it we set out to make ourselves part of the community, to work with the First Nations, and to work to preserve habitat by using helicopters and smaller logging equipment so as to make a smaller imprint on the environment.” By attempting this, Interfor generally managed to avoid the high-profile bad publicity and disruptions to its operations that MacBlo was experiencing, although its local offices periodically attracted groups of protestors holding signs with slogans like “Interfor—Clear-cut Destruction.” Interfor continued harvesting in Clayoquot Sound, although in smaller cutblocks than MacBlo and Fletcher Challenge. Its largest clear-cut of 1994 measured 31 hectares, but as Frank Harper pointed out in The Sound in January 1994, “31 hectares is about the size of greater Tofino.”

Around the time Interfor appeared on the scene in 1991, BC’s Ministry of Forests released a discussion paper as it prepared to develop its Forest Practices Code, which would eventually become law in 1995. After years of rapacious logging practices, signs of change were beginning to appear in British Columbia’s forest industry, but these changes were not happening nearly fast enough for some.

International publicity decrying logging practices in British Columbia mounted steadily in 1991, largely due to the efforts of Greenpeace Canada through its connections with environmental groups abroad. Several European countries began discussing the possibility of banning Canadian wood products from old-growth forests. In March 1991 a German television program, A Paradise Despoiled, came up with the phrase “Brazil of the North” to describe the effects of clear-cutting, and in December 1991 the British newspaper The Observer published a four-page feature accusing the BC forestry industry of a “chainsaw massacre.” More such coverage would follow.

In January 1992, NDP premier Mike Harcourt’s new provincial government announced the formation of an independent and impartial Commission on Resources and the Environment (CORE), which would create a land use plan for every region of BC. Headed by Stephen Owen, CORE possessed a mandate to consult local interest groups, including environmental organizations and First Nations, about land use, forest practices, and stewardship, encouraging consensus on these issues. Clayoquot Sound was not included in the CORE process because of the ongoing deliberations of CSSDTF and CSSDSC, then trying to reach agreement on how best to deal with short-term logging in the Sound. Nonetheless, Owen’s final report would undoubtedly have ramifications for the Sound.

Early in 1993, Greenpeace, the Sierra Club, and a coalition of other environmental groups began their international campaign in earnest. Drawing on their wide membership, and using their proven ability to attract media attention, they spread the news of Clayoquot Sound’s clear-cuts around the world. In January, the New York Times ran a full-page advertisement headlined “Will Canada do nothing to save Clayoquot Sound, one of the last great temperate rainforests in the world?” The ad named many Hollywood stars who lent their support to the protests, including Tom Cruise, Nicole Kidman, Robert Redford, Tim Robbins, Martin Sheen, and Oliver Stone. Activists placed prepared articles in leading European, American, Asian, and Latin American newspapers, using the term “Brazil of the North” for Clayoquot Sound, and publishing graphic pictures of clear-cuts. Protests organized by different environmental groups took place in front of Canadian embassies in a number of countries, and talk of boycotting Canadian wood products continued.

All the while, the provincial government had been planning its own form of action. On April 13, 1993, Premier Mike Harcourt descended from a helicopter at Radar Hill and announced his government’s Clayoquot Sound Land Use Decision. Billed as a “compromise solution,” the decision allowed the forest companies to log 62 percent of the Sound, while placing 17 percent of the old growth in the Sound under “special management.” The decision also promised to end clear-cutting, to set higher standards for logging road construction, and to monitor more closely the logging practices of forest companies. Those companies generally welcomed the decision, although not all were happy. “That decision reduced Interfor’s allowable cut from 171,000 cubic metres to 66,000 cubic metres—a reduction of over 60 percent,” said Dean Wanless of Interfor. “Which made it ever more difficult to run a profitable forestry operation.” In addition, as part of the land use decision, the government promised to work to establish a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve in Clayoquot Sound.

The details came as a complete shock to most environmentalists. Viewing the Clayoquot Sound Land Use Decision as a call to arms, the Western Canada Wilderness Committee, Friends of Clayoquot Sound, the Temperate Rainforest Alliance, and the Valhalla Wilderness Society all immediately resigned from the ongoing CORE deliberations, unwilling to put any further trust in government-led environmental initiatives. Many also saw the Clayoquot decision as a conflict of interest, as the BC government had purchased $50-million worth of shares in MacBlo in February 1993, making the government one of the company’s largest shareholders. Without doubt, the badly handled and badly timed decision provided the spark that ignited the largest protest in Canadian history, leading to the largest mass arrests in the country, and drawing national and international media attention. The San Francisco Chronicle published a lengthy front-page story about the decision, again repeating the “Brazil of the North” slogan.

Shortly after the Harcourt government announced its decision, another bridge came under siege in Clayoquot Sound. In May, Michael Mullin and two others attempted to set fire to the Clayoquot Arm Bridge in an effort to cut access to most of MacBlo’s logging sites in the Sound. They were arrested, given short jail sentences, and ordered to do community service. Mullin did his for FOCS; he had been a director of the organization but resigned when he was arrested.

As the summer of 1993 approached, FOCS prepared to take action. At one of the early strategy meetings, the six people present boldly proposed they try to draw a large number of people to Clayoquot Sound, maybe as many as 200, for a mass protest. In hoping for 200 people they were “dreaming big,” according to Tzeporah Berman. Building on a base of support from other organizations, they sent out invitations for participants to attend training sessions on civil disobedience and non-violent protest, and to learn about the rainforest and media skills. The first training camp took place at Clayoquot on Stubbs Island in early June 1993. The headline in the Westerly News declared “Learning Disobedience in Tofino,” and the accompanying article described people attending from as far away as California and Germany. The organizers had expected a hundred or so people; 250 showed up. Another highly visible training camp took place in Stanley Park in Vancouver, attracting several hundred people, with news reporters in attendance. Central to the training were principles of non-violence and civility, and all participants had to agree to FOCS’s code of conduct: “We will not run, we will not shout and will carry ourselves in a calm and dignified manner; we will respect all other beings; we will carry no weapons and we will not be under the influence of drugs or alcohol when at a function in public.”

FOCS began to realize its movement might grow into something far bigger than anticipated; the group hired eight people to coordinate events for the summer, and other environmental groups mustered resources, support, and strength to face a summer of protest. Faxed notices sent to the media said only “Clayoquot Blockades will start July 1,” providing no details in the hope of exciting curiosity about what lay ahead. By the end of June, a small group began to set up tents and a makeshift kitchen for what would become the Clayoquot Peace Camp.

Hundreds of people from across Canada and from the United States, Mexico, Australia, and Europe began converging on the Sound. Galvanized into action by all the publicity about clear-cut logging, they gathered at the Peace Camp. It opened on Canada Day, July 1, 1993, in an old clear-cut commonly called the “Black Hole,” which had been burned to allow for natural regeneration. One of the ugliest examples of logging practices, the Black Hole lay right beside the Tofino–Alberni Highway a few kilometres east of the Ucluelet–Tofino junction. Mountainsides defaced by washed-out logging roads and mudslides, and huge piles of logging slash, provided a backdrop for the camp, vividly illustrating what the environmentalists were protesting and offering a dramatic background for media pictures and interviews.

The organizers hired Tzeporah Berman, a twenty-four-year-old graduate student from the University of Toronto, to coordinate and run the camp—an extraordinary challenge given the magnitude of what followed. Some 10,000 to 12,000 people passed through the Peace Camp by the time it finally closed on October 9, 1993, and throughout that time it exemplified the non-violent principles of civil disobedience observed by Mahatma Ghandi in India against British rule, and by Martin Luther King in the American Civil Rights movement. “I was very concerned about making sure that the protest would be peaceful,” said Berman. “We organized mandatory training sessions in non-violence every day. We developed talking circles as a way of decision-making, and we gave people a sense of ownership in the process.” Over that summer, women comprised an estimated 80 percent of those staying in the camp, many inspired by the eco-feminist successes of the Women’s Pentagon Action in the United States, and the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp in Britain. Jean McLaren, one of the earliest of the “Raging Granny” protesters in British Columbia, brought her experience of the Civil Rights movement and Greenham Common to the Peace Camp. Having been arrested in 1992 at another logging protest, and banned from going within 200 metres of any logging road in the province, she stayed put in the camp for four months, giving daily training sessions in non-violent communication and peacekeeping skills.

While previous protests and logging blockades on Meares Island, at Sulphur Passage, and at Bulson Creek had taken place in relatively inaccessible locations, the Peace Camp could not be missed; anyone travelling toward Tofino and Ucluelet had to see it. Similarly, all of the logging blockades and protests during the summer of 1993 took place at the readily accessible Kennedy River Bridge, giving the media unprecedented access to all the action. “One of the reasons the Clayoquot protest grew so big so fast,” said Vicky Husband, of the Sierra Club, “was that people could easily drive to the area and see for themselves the horror show of what was going on with the logging.” The protests gained momentum far faster than anyone expected. In early August, FOCS campaign organizer Valerie Langer commented in a CBC News interview, “When we started this five weeks ago we were told it would fizzle in a week. Look at this! If this is a fizzle let’s keep fizzling.”

Each morning at 4 a.m., activists formed a motorcade at the Peace Camp and drove up the West Main logging road leading off the highway opposite the camp. They travelled about ten kilometres, to the Kennedy River Bridge, where the protestors, often carrying signs with slogans like “No Trees, No Fish, No Jobs” and “No Fish, No Forests, No Future,” took their positions, waiting for the trucks. Some people sang, some drummed, many linked arms. Some stood beside the road; others sat or stood directly on the logging road, forming a human barrier in front of the bridge as a cavalcade of logging trucks, crummy wagons, and RCMP vehicles arrived. “All of the laughing and the talking and the drumming and whatever was happening would just end,” said Berman. “There’d be complete silence as all of the people of different ages and different backgrounds stood in front of the trucks.” An RCMP officer would then inform the protestors that they were breaking the law—both MacBlo and Interfor had taken out court injunctions preventing protests. When the protestors refused to move, officers began making arrests, often carrying those arrested to a nearby bus, which then transported them to the athletic centre in Ucluelet to be processed. Those who stood by the side of the road and chose not to be arrested that day would return to the Peace Camp for one of the meals, cooked three times each day in the camp kitchen, that fed 200 people at a time with donated food.

The well-organized, peaceful blockades aimed to attract the broadest possible support and to encourage more and more ordinary citizens to join the protest. The daily ritual continued all summer long. By September, 932 people had been arrested, the single largest mass arrest occurring on August 9, when it took RCMP officers seven hours to arrest 309 protestors. The protests and arrests garnered increasing worldwide media attention as the environmental movement kept up, and won, the publicity battle. Marches and demonstrations in support of Clayoquot protesters took place in Vancouver, Munich, Bonn, London, and Sydney, Australia.

“We wanted to run a campaign that raised a profile beyond Vancouver Island,” said Valerie Langer. “We wanted to run it in a media-savvy style, one that your grandma would feel comfortable joining.” The protesters sustained a clear, well-planned media campaign, every day presenting news outlets with ready-made copy. As well, by continually offering reasoned solutions to the problems at hand, the movement garnered more credibility, while the logging companies and the government looked and sounded completely unnerved. The events of the summer provided rich fodder for the crowds of reporters, given the almost daily scenes of police dragging off peaceful, non-violent protesters from all walks of life, the highly photogenic surroundings, the scenes of devastation on the surrounding hills.

Nonetheless, journalists had their work cut out for them in that pre-digital age, as CBC television reporter Eve Savory vividly recalled.

Robert F. Kennedy Jr., then an environmental lawyer in Washington D.C., made an appearance in support of the protestors, as did Tom Hayden and the Greenpeace-sponsored enviro-rock band Midnight Oil. The band flew from Australia to play a concert in front of an estimated 5,000 people at the Black Hole in mid-July 1993. The band’s towering, six foot six, arm-swinging, bald-headed lead vocalist, Peter Garrett, encouraged the crowd to continue its protest, declaring he was “bugged by a government who bought shares in the forest industry prior to making a pro-logging land use decision like Clayoquot,” and he found it “scandalous, immoral and improper.” Renowned environmentalist David Suzuki sat in the front row near the stage, which was constructed of burned wood from the Black Hole site. The international press turned out in force for the event.

Matt Ronald-Jones, who worked at the newly opened Middle Beach Lodge, where the band stayed, recalled cars parked on both sides of the road for kilometres leading to the concert site, and noted that a cloud hung over the clearing from all the marijuana being smoked. “After the concert we were heading back to my car, when I saw a brand new Pontiac Trans-Am sports car loading passengers by the side of the road. The door sat open. Just then a crummy wagon full of loggers came up the road moving pretty fast. Seeing the open door of the Trans-Am the crummy driver didn’t slow down one bit…and the big van ripped the door clean off that Trans-Am and kept right on going. It was something to behold!”

“The loggers were angry and frustrated,” reporter Eve Savory commented. “Most of the protesters were young females who spoke softly and sang. What’s an angry man to do? Yes, there were many angry words, but my impression was they felt baffled, out of their depth, deeply frustrated, and probably deeply anxious. With good reason.” Some of the loggers had spent decades of their lives in the forest; they took pride in their work, and they could not begin to comprehend this mass opposition to everything they had ever done, much of it coming from people who did not know the area at all. Small wonder anger erupted. Tzeporah Berman received so many death threats on her voice mail that a colleague began filtering them so she would not hear any more; she also received anti-Semitic hate mail. Opponents often targeted the Peace Camp, leaning on horns in the middle of the night, throwing stones at tents, and harassing people from the gates. Tensions rose in Ucluelet and Tofino, with families becoming estranged, car and truck tires being slashed, boats being sunk. Warring bumper stickers could not begin to reveal the depth of feeling in the area; “Logging Feeds My Family” and “Hug a Logger, You’ll Never Go Back To Trees!” only hinted at how threatened the logging community felt.

In mid-August 1993, the logging-industry-sponsored pressure group Share BC organized a two-day rally in Ucluelet to express support for the government’s Clayoquot Sound Land Use Decision, and to bring loggers together in a show of solidarity. Some 5,000 loggers and their supporters from all over BC came to Rendezvous ’93, billed as a “protest against the protesters” in the Westerly News. Many participants sported yellow ribbons and T-shirts, and “along with the yellow were countless yells, yells everywhere of support for the embattled loggers of the West Coast…The yellow army rallied in support of the government and encouraged it time after time to stand its ground on the decision.” Rousing speakers urged the local loggers not to lose their backbone, with Jack Munro of IWA-Canada saying, “Maybe you feel by yourselves in the morning some days, but we’re sure as hell there with you, we appreciate you keeping your cool.” Gerry Stoney of the IWA stated, “This will be a moment of truth that will put an end to the distortion and plain unadulterated BS that the preservationists are feeding to the people of BC and the world. I want to say to anyone watching on TV or listening on the radio, folks you’re being swindled, you’re being conned, you’re being lied to by the so called leading lights of the environmental movement.”

As the summer of 1993 wore on, the RCMP continued their arrests, which came to include women from the Raging Grannies, one of them eighty-one years old. One day four grandmothers linked arms with MP Svend Robinson and several others, “and all launched themselves and Clayoquot into the international sphere with the simple words, ‘No, I will not move,’” as Valerie Langer wrote later. A great-grandfather of eighty was arrested, children as young as eleven and twelve, Anglican priests, professors, lawyers, teachers, doctors, high school students, politicians, Indigenous people, and even some loggers. “Theme days” saw only people from specific groups blockading: on one day, those from the Gulf Islands; on another, artists, including nature painter Robert Bateman; and on it went, with people of faith, business and professional people, tourists, foresters, and even deaf people taking their turns to be arrested.

In his autobiography, Premier Mike Harcourt wrote: “But despite the protest, the arrest of almost eight hundred protestors and the Greenpeace-inspired boycotts, I was not about to give in to the protestors. I was not about to give in to the clear-cutters either. I was not about to give in to the forest industry. I was not about to give in to aboriginal demands. I would most certainly not give in to the likes of [Robert] Kennedy’s grandstanding. He said he was outraged over our decision. I wrote of him and his ‘outrage’ that ‘he was asking loggers and forestry workers to live off their inheritance—just like he does.’”

In August 1993, the first of a series of eight trials began before Justice John Bouck in the theatre of the Royal BC Museum in Victoria, the number of defendants so great that the provincial courthouse proved too small. In order not to clog the courts, protestors were tried en masse, leading to complaints of Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms being violated and basic legal rights denied. The first trial of forty-four protestors continued for five weeks; the rest followed in 1994. Most of those arrested faced criminal contempt charges for defying MacBlo’s court injunctions rather than the charge of civil contempt, which carried a less severe penalty. Even though the court documents stated that the case pitted MacMillan Bloedel against John and Jane Doe, no MacBlo lawyers appeared in court, as they would have done had the protesters faced civil contempt charges. Instead Crown counsel from the Attorney General’s office prosecuted the case, which made it look like the province of British Columbia had quietly taken over the prosecution of the cases for MacBlo. As lawyer Jim Miller stated, this left the impression “that the Attorney General is joined at the hip with MacMillan Bloedel.” By taking over the prosecution, the Attorney General’s office saved MacBlo thousands of dollars in lawyers’ fees, passing those expenses on to the province’s taxpayers.

Most of the accused appeared in court for the first time in their lives. Most appeared without lawyers to represent them and could not opt for trial by jury or call witnesses to appear in their defence. The court denied them the opportunity to explain why they had stood on the road at the Kennedy River Bridge. Each defendant was asked: “Were you there? Did you hear the injunction read?” In most cases, videotaped evidence provided by MacBlo proved the defendant had been there, and then the defendant was found guilty because, as the judges stated over and over, “If you were on the road and knowingly disobeyed the injunction, then you are guilty. That is the law.” The judges imposed widely inconsistent sentences: fines ranging from $350 to $3,000; sentences ranging from suspended sentences to six months in jail, and sometimes probation. MP Svend Robinson received a fourteen-day sentence. Local doctor Ron Aspinall was slapped with sixty days in jail and a $3,000 fine. When two of the arrested grandmothers—Judith Robinson, aged seventy-two, and Betty Krawczyk, sixty-five—refused to sign undertakings that they would stop protesting, they each served eighty-five days in prison. At one point during their sentence they were transferred by air, with another older woman, from Nanaimo to Victoria, a trip made “unbelievably complicated by the leg shackles and handcuffs we were forced to wear,” wrote Betty. “Three grandmothers in leg irons for protesting the demolition of one of the world’s last old growth rainforests! Lord have mercy on us.” The severity of some of the sentences came as a terrible shock; many of those participating in the blockades had expected to do community service, not to be taken from the courtroom in handcuffs by a sheriff.

Tzeporah Berman had always made sure she was not on the road among those willing to be arrested. Nonetheless, one day the RCMP arrested her from the side of the road and charged her with aiding and abetting the commission of 857 criminal acts. The charge, which potentially carried a six-year prison sentence, outraged prominent criminal lawyers Clayton Ruby of Ontario and BC’s David Martin. They stepped up and defended Berman pro bono. “A Macmillan Bloedel representative [admitted] during the trial that the firm had lobbied for months to have the charismatic woman arrested,” reported Kim Westad in the Victoria Times Colonist. In rendering his decision after Berman’s four-day trial, Justice Richard Low opened with harsh words for the Crown, then dismissed the case. In 2013 the “whacked-out nature worshipper,” as one TV reporter dubbed Berman, received an honorary degree from the University of British Columbia, and today she appears on a list at the Royal BC Museum of 150 people who have “changed the face of British Columbia.”

Following their sentencing, each defendant reserved the right to speak to sentencing, giving rise to eloquent and moving statements. Peter Holmes stated, “I believe that these trials themselves are doing at least as much to bring the administration of justice and the courts themselves into disrepute as, and probably quite a bit more than the original actions of the arrestees that triggered these trials.” Margaret Ormond said, “I went to Kennedy Bridge, not as an environmentalist…but as a private citizen, out of concern for the world my children and grandchildren will inherit.” Carol MacIsaac said, “We are at a point in history where direct and urgent action is needed. If it does not come from government then it must come from people of conscience.” Kim Blank went on record saying, “The idea that the democracy of Canada has been threatened by the Clayoquot protestors is overstated. If our wonderful country is truly threatened by the action of a few protesters sitting quietly on a dirt road in the middle of the night, then it is time to hang up the old hockey stick and move to a different planet.” George Harris, a logger arrested with his two sons Adam, twelve, and Tyson, eleven, concluded his submission: “I was thinking what the parents of the eleven and twelve-year-old children said in Nazi Germany in the 1940s when their Jewish neighbors were taken away to be exterminated. This was done legally, this was done with everyone’s knowledge. What did parents say? What will I say when my children grow up and look at the destruction of this province? I will say that I stood with my friends on the line at Clayoquot Sound. Thank you, Your Honor.”

The arrests, the trials, and the convictions did nothing to stop the protests. Instead, environmental groups broadened their horizons, organizing a “markets campaign.” Careful research into which companies used paper products manufactured from logs harvested in Clayoquot Sound led the protesters to large American companies like Scott Paper and Pacific Bell Telephone. Faced with demonstrations in front of their offices and factories, and with activists offering to place stickers on their products bearing slogans like “I destroy rainforests” and “Let your fingers do the chopping,” the companies, fearing negative publicity, cancelled their orders. “Things didn’t turn around until we worked with international markets for wood products,” said Valerie Langer. The activists expanded their campaign to Europe and organized boycotts of MacBlo products in England, Australia, Germany, and Austria. According to author Lorna Stefanick, “In Britain activists were arrested for chaining themselves to the doors of Canada House; in Germany, Sweden, Australia, Italy, Japan and India groups protested the logging of Clayoquot Sound outside Canadian embassies and consulates.” The environmentalists brought with them a 3,600-kilogram red cedar stump, two metres in diameter, that was reckoned to be a young 390 years old—given that some cedars live to 1,500 years. Named “Baby Stumpy,” it toured North America before Greenpeace transported it to Europe, where it fascinated thousands and became a powerful symbol for the anti-logging campaign. European corporations began cancelling contracts with MacBlo. “They canceled over five million dollars in contracts in England and at least that much in Germany,” said Langer. “We were called ‘traitors’ by company executives and provincial officials.” She said that the publicity campaign in Europe and the United States “linked with the campaign for alternative paper fibers, recycling and reduced paper consumption. It was the most outrageously reasonable campaign. There is no question that ancient forests should not be used for telephone directories and newspapers.”

In October 1993 the Harcourt government launched a two-pronged strategy to defuse the situation. It first established a nineteen-member Scientific Panel for Sustainable Forest Practices in Clayoquot Sound, headed by Dr. Fred Bunnell, with Nuu-chah-nulth hereditary chief E. Richard Atleo as co-chair. The panel set out to find the most scientifically rigorous standards for environmentally sustainable logging. In March 1994, the BC government signed an Interim Measures Agreement with the Nuu-chah-nulth. This put land use decisions for Clayoquot Sound into the hands of a ten-member board made up of First Nations and provincial representatives, giving the First Nations a veto over all decisions, pending the completion of treaty negotiations. The Interim Measures Agreement also gave First Nations in Clayoquot Sound $4.5 million over two years for economic development. This agreement drove a wedge between First Nations and the environmental movement,

In the meantime, in February 1994, Stephen Owen released his CORE report recommendations. Although Clayoquot Sound had been excluded from his deliberations, among his recommendations he proposed preserving 13 percent of the rest of Vancouver Island as wilderness. He recommended that the government create new logging practices and standards, and impose heavy penalties for non-compliance; provide funds to oversee resource and environmental management in Clayoquot Sound; create a biosphere reserve in the Sound; and receive and respect policy advice on land use allocations reached by consensus at regional tables. Owen also asked that the Conflict of Interest Commissioner investigate the provincial government’s purchase of shares in MacBlo.

The CORE recommendations riled loggers all over BC, many of whom united behind the Share BC movement. They viewed the CORE recommendations as an assault on their livelihood that would eliminate 3,500 forestry jobs, cost $42 million in wages, and devastate their industry. On March 21, 1994, Share BC staged a massive event at the Legislative Buildings in Victoria, drawing a crowd estimated at between 14,000 and 20,000 loggers and their supporters, many wearing yellow ribbons. They came from all over Vancouver Island and elsewhere in BC, travelling by bus and in cavalcades of cars and logging trucks to hold the largest demonstration ever seen at the legislature. This rally, targeted not only the government and Owen’s CORE recommendations, but also, as Jack Munro of the IWA put it, “the cappuccino-sucking, concrete-condo-dwelling, granola-eating city slickers” who supported the environmentalists. Premier Harcourt tried to address the volatile gathering, saying he would not approve the CORE recommendations, only to be drowned out by the protestors.

The summer of protest in Clayoquot Sound did not for a moment stop the logging. As Tzeporah Berman put it in This Crazy Time, “MacMillan Bloedel was still logging Clayoquot as quickly as they could” through the summer of 1994. By then hired by Greenpeace as a campaigner, Berman asked that organization to send its mother ship to Clayoquot Sound to protest the continued logging at Bulson Creek. When it emerged that Nuu-chah-nulth leaders did not want Greenpeace protesting in the Sound because they valued the jobs provided by logging, long and difficult negotiations ensued. Moses Martin, chief councillor of the Tla-o-qui-aht, pointed out to Berman and her colleagues, “You have to understand you’re concerned about the trees and the wildlife, and many of us share those concerns, but we’re also carrying…the highest suicide rates in Canada, we have the highest unemployment rates in Canada, and our people are struggling so hard to survive that our culture and language are dying.”

In May 1995, Dr. Fred Bunnell’s nineteen-member scientific panel released its report, setting out new guidelines for forest practices in Clayoquot Sound and providing over 170 recommendations that would make forestry in this area “not only the best in the province, but the best in the world.” The report emphasized that “the key to sustainable forest practices lies in maintaining functioning ecosystems and that planning must focus on these ecosystems rather than on resource extraction.” It recommended that clear-cutting be replaced by variable retention forestry, an approach that would leave some trees standing in each area in order to protect the health of the forest ecosystem. The panel stated that the cultural values of the inhabitants of the Sound must be respected, and study of the scientific and ecological knowledge of Clayoquot Sound must continue. It also reduced the size of cutblocks, called for alternative harvesting measures, such as helicopter logging, and for sustainable forestry, with improved replanting and “greening” methods. The government could impose fines of up to a million dollars if the guidelines were not followed. Most of these measures had already been in place for months, many recommended a year earlier in Stephen Owen’s CORE report. In July 1995, the government accepted most of the recommendations of the Clayoquot Scientific Panel.

By 1997, logging in Clayoquot Sound had been reduced to a tenth of what it was in 1991, with MacBlo recording losses of more than $350 million due to the limitations imposed by the Scientific Panel for Sustainable Forest Practices. In 1998, losses in sales of $1.1 billion forced the logging industry to cut jobs and close mills. Interfor closed its office in Tofino that year. The downturn forced MacMillan Bloedel, represented by Linda Coady, a Vancouver lobbyist who had been appointed vice-president of Environmental Affairs, to begin private talks with the Nuu-chah-nulth First Nations and five environmental organizations. The talks resulted in a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) signed on June 16, 1999, establishing a joint venture between MacBlo and Ma-Mook Development Corporation, a Nuu-chah-nulth-owned company, to create Iisaak Forest Resources Ltd. (“Iisaak” means respect). Ma-Mook would control 51 percent of the new company and MacBlo 49 percent, with MacBlo handing over its Clayoquot Sound tree farm licences to Iisaak.

In accepting this mandate, Iisaak became the only company licensed to operate in the Sound, and it agreed to follow rigorous guidelines set out in the not-legally-binding MOU. The guidelines specified logging could only occur outside the intact old-growth valleys of the Sound, using only existing logging roads, and conducting what a MacBlo spokesman characterized as “boutique logging.” All of the environmental groups save Friends of Clayoquot Sound, which had reservations about the compromise, promised to support Iisaak and help it look for new markets for its products. Twenty-four hours after signing this MOU, multinational giant Weyerhaeuser announced that it had bought MacBlo for $2.45 billion.

While all these protests and studies and discussions were taking place, the federal and provincial governments continued quietly working behind the scenes with the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) to have the United Nations declare Clayoquot Sound an international biosphere reserve. For many decades, scientists had recognized the unique biodiversity of the old-growth forests and the richness of marine life on the west coast, but much still needed to be learned. Between 1989 and 1991 a group of researchers, including Jim Darling, Kate Keogh, Josie Cleland, Karena Shaw, Mike Marrell, and Wendy Kotilla, worked in conjunction with the Nuu-chah-nulth of Clayoquot Sound to assemble “a scientifically acceptable pool of knowledge about the region that simply would not exist otherwise,” according to Jim Darling. Their wide-ranging work addressed “what species are present and which areas are important to them and why...stream inventories, fish habitat mapping…amphibian surveys, dragonfly inventories, microclimate projects and more.”

On May 5, 2000, Prime Minister Jean Chrétien and Premier Ujjal Dosanjh unveiled a plaque in Pacific Rim National Park declaring that the UN had designated Clayoquot Sound a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, one of over 600 worldwide. This designation gave international recognition to Clayoquot Sound’s biological diversity, “promoting and demonstrating a balanced relationship between people and nature.” The designation did not mean the UN would exert any control over the Sound, nor did it mean an end to logging or mining in the region. As a biosphere reserve, all stakeholders would work to balance conservation with sustainable economic, social, and cultural development. First Nations would be allowed to continue logging in a sustainable manner within the reserve. Both the federal and provincial governments allocated funds to “support research, education and training in the Biosphere region,” with the federal government contributing $12 million to establish the Clayoquot Biosphere Trust.

In the end, the “War in the Woods” of 1993 saw the environmental movement change the face of logging in British Columbia. It managed to shut down logging by multinational companies in Clayoquot Sound, paving the way for the Nuu-chah-nulth-owned Iisaak to become the only company working in the area. The activists’ actions helped transform how forestry would be conducted in the province. The Forest Practices Code of 1995 brought immediate changes, and additional regulations have since refined that original legislation. Roads that once slid down mountainsides are now made to stay in place, fish-bearing creeks and wildlife habitat are better protected, clear-cuts are limited in size.

Yet although 60 percent of Clayoquot Sound now stands protected from logging, chainsaws are still at work there. In March 2007, a First Nations company, Ma-Mook Natural Resources Ltd., bought Interfor’s 49,000-hectare tree farm licence in Clayoquot Sound. In order to finance the purchase, Ma-Mook entered into a joint venture with Coulson Forest Products, a logging company from Port Alberni, and soon lobbying began to allow logging in the intact watersheds of Clayoquot Sound. Although Ma-Mook’s alliance with Coulson Forest Products lasted only three years, leaving Ma-Mook in sole charge of the company’s timber holdings in the Sound, pressure to log areas of old growth still exists. Yet everyone involved in the forest industry knows that highly motivated individuals and vigilant environmental groups like Friends of Clayoquot Sound, Western Canada Wilderness Committee, and the Clayoquot Action group continue to keep a watchful eye on logging practices. No one in the business wants to attract the adverse publicity or reignite the bitter conflict of the early 1990s. For now, the unlogged, pristine valleys and watersheds that remain in Clayoquot Sound may stand intact, but if one lesson has been learned from the events of the late twentieth century, it is that nothing here should ever be taken for granted.

In April 2014, on the thirtieth anniversary of the Meares Island Easter Festival and the Tla-o-qui-aht declaration of Meares as a Tribal Park, a group gathered in Tofino to commemorate this landmark event that kick-started so many years of protests against logging in Clayoquot Sound. Central to the celebration, Godfrey Stephens’s five-metre-high carving Weeping Cedar Woman returned to Tofino after many years in his workshop in Victoria. Unveiled at her temporary location outside the Tofino Community Hall, Weeping Cedar Woman now stands fully restored, her tears flowing in cascades, one hand held out defensively, the other pointing at the earth.

The non-violent campaign conducted by protesters at the Kennedy River Bridge in 1993 became a template for environmental movements around the world. The Great Bear Rainforest campaign, Occupy Wall Street, Idle No More, the fight to stop the Enbridge Northern Gateway and Keystone XL pipelines, and the struggle to prevent old-growth logging at Fairy Creek have all been influenced by the landmark protest in Clayoquot Sound. The events of 1993 also brought the Nuu-chah-nulth to the forefront of treaty negotiations, which the provincial government had been reluctant to begin. By signing an MOU with the Nuu-chah-nulth in March 1994, it took the first step in beginning the treaty-making process.

The protests of 1993 brought the quiet, rain-drenched town of Tofino onto the world stage in ways no one could have foreseen, initiating irreversible changes in the community. While media exposure during the protests put the devastation of clear-cut logging on the television screens of millions of viewers around the world, many reports juxtaposed shots of clear-cuts with stunning images of the pristine areas of the Sound. Displaying the wildlife, the beaches, the mountains, and the great forests of the west coast at their best, such coverage acted as a massive and immediate tourist magnet for the area. “Thank God for all the protests,” said Gary Richards of Tofino Air, recalling the impact on his business. “Everyone wanted to hire us to fly them out to see the old-growth forest. They wanted to see the last big trees before they were cut down.” Others wanted to see just the opposite. One German tourist reportedly arrived in Tofino and immediately ordered a float plane pilot to “Take me to a clear-cut!” Float planes flew many international journalists over clear-cuts, old-growth forests, glorious beaches, glaciers, and then out to sea to spot grey whales, all in one flight.

Since that time, people have arrived in droves. In the scramble of development throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, Tofino has at times been overwhelmed by its own popularity, for preserving the beauty of the area, and sharing it with others, has come at a price. “One day all the West Coast territory will be opened up,” declared Dorothy Abraham some seventy years ago in Lone Cone, “and one day it will be the greatest playground of the Pacific: people will swarm in, and the silence will be broken.”

She was absolutely right.