Chapter 3: The King George Men

For European explorers, the northwest coast of North America remained terra incognita for a very long time. Their voyages of exploration took them far and wide around the globe, yet not into the uncharted North Pacific, so distant and difficult to reach. To travel there from Europe meant braving a six-month voyage over vast and dangerous distances, sailing into the South Atlantic, around Cape Horn at the southern tip of South America, then up the west coast of South and North America. Russian explorers and traders approached from a different direction, making a three-year journey across Europe and Asia, then a sea voyage across the Bering Strait to the coast of Alaska.

Before the mid-eighteenth century, few dared consider such journeys, but by the end of that century, five maritime nations—Russia, Spain, Britain, France, and the newly formed United States of America—vied for control of the Pacific Northwest. They pursued a high-stakes trade in sea otter pelts there, and in some cases established permanent trading posts.

In the late 1700s, as early Canadian settlers struggled to gain a foothold in the eastern provinces, the lands west of what is now Manitoba lay virtually unexplored by newcomers, save for a limited number of isolated fur trading posts. The exploration and settlement pattern common to most of North America, with settlers steadily moving by land from east to west, did not hold true on the northwest coast of Canada. By the time Alexander Mackenzie famously crossed the continent from east to west in 1793, emerging near Bella Coola, the coast was already internationally renowned, and trade vessels from several nations visited regularly. With the frenzied trade in sea otter pelts underway, the coast became part of a territorial tug of war and an economic boom so lucrative it nearly precipitated a war between European powers. All this occurred before the Rockies had been mapped; before the great rivers of the Canadian west, the Skeena, Peace, Fraser, Thompson, and Columbia had been navigated by European explorers; before even one-quarter of North America had been mapped.

The first Europeans to arrive on the west coast of Vancouver Island and to make contact with Indigenous people appeared in 1774 aboard the twenty-five-metre frigate Santiago, sailing under the Spanish flag. Captain Juan Josef Pérez Hernández had been sent north by his superiors at San Blas, the Spanish naval base on the west coast of Mexico established by Spain in 1768. Pérez had instructions to explore the uncharted northern waters, to investigate reports of Russian activity in Alaska, and to lay claim to what Spain considered its territory. After sailing to the northern end of Haida Gwaii, Pérez returned along the coast of Vancouver Island. He anchored off what are now called Perez Rocks near Estevan Point on August 7, 1774, the sight of his ship exciting astonishment and fear among the witnesses on shore. Many who saw the strangers fled or hid, but a number of Hesquiaht warriors approached cautiously in their canoes, and the first coastal trading took place; Pérez and his crew obtained otter skins and conical hats in return for knives, cloth, and abalone shells from California beaches. Increasing winds prevented Pérez from going ashore with the large 4.2-metre-high cross his crew had made, intending to plant it as a formal Spanish claim to the area. The winds continued to increase overnight, and Pérez found himself in danger of going onto the rocks. Unable to hoist his anchor, he was forced to cut the cable and put out to sea. Before leaving, he named the head of the peninsula at Hesquiaht Harbour Punta San Esteban—Estevan Point—for officer Esteban José Martínez, who later played a leading role in Nootka Sound when the Spanish returned.

Spanish authorities found Pérez’s voyage a disappointment: he had not formally claimed territory, he had not gone far enough north to encounter the Russians in Alaska, nor had he produced a detailed chart. His pilot did, however, draw a coastline map of British Columbia, the first ever made, showing Nootka Sound and part of Haida Gwaii. Because Pérez and his men did not actually go ashore and ceremonially lay claim to the land, the British would later refuse to acknowledge Spanish sovereignty over the area. This lack of foresight on Pérez’s part would prove costly to Spain.

Four years after Pérez’s voyage, on March 29, 1778, British captain James Cook landed at Nootka Sound, which he named King George’s Sound. Although the extraordinary navigator Cook is widely acknowledged as the first explorer to set foot on the coast of British Columbia, theories of other, earlier explorers reaching the coast have surfaced over the years. Some archaeologists speculate that a Chinese Buddhist priest named Hui-shen, may have visited the North America continent, which the Chinese called Fusang, in 458 A.D. Many centuries later, further Chinese contact may have occurred. According to Gavin Menzies in his book 1421: The Year China Discovered America, Chinese junks could have sailed in BC waters in 1423. Menzies also points out that Vancouver Island appears on the Waldseemüller map, published in 1507, 250 years before Europeans “discovered” coastal BC. A later chart, published by Venetian Antonio Zatta in 1778, the same year Cook arrived at Nootka, names Haida Gwaii as Colonia dei Cinesi. Another notion suggesting a possible early arrival appears in Sam Bawlf’s book The Secret Voyage of Sir Francis Drake. Bawlf maintains that the explorer Sir Francis Drake secretly sailed his Golden Hinde along the coast of BC in 1579, 200 years before Cook. He claims Drake circumnavigated Vancouver Island, sailed through Juan de Fuca Strait, and identified the area around Comox and Courtenay as a possible site for a future English colony, to be named New Albion. All of these “earliest” explorer theories and claims remain contentious.

No one disputes the arrival of Captain James Cook. On his third circumnavigation of the world and in search of the Northwest Passage, Cook and his men sailed their two ships, the Resolution and the Discovery, into Nootka Sound seeking a sheltered bay in which to make repairs to the storm-battered vessels. After finding a temporary anchorage for the first night, Cook navigated a short distance into the Sound and dropped anchor in Resolution Cove (Ship Cove), off Bligh Island. Cook named the island after his midshipman William Bligh, later to become famous as captain of HMS Bounty.

The braver among the local Mowachaht approached in several canoes and remained nearby, standing off the ship in complete silence for many hours. “My forefathers, on seeing [the white men] thought they were the dead returning,” wrote August Murphy of the Mowachaht First Nation. “The hunters returned to the village with the astonishing news that they had seen a floating house on which a strange people lived and moved around on the waters. They expressed it in a single word that to this day describes the people who have come after them, ‘Mamuthlne.’” In an interview for the Sound Heritage series, Peter Webster of Ahousaht explained further, stating that the Nuu-chah-nulth word, sometimes written as mamalth’ni, “means that you are living on the water and floating around, you have no land.” According to Webster, right after seeing the ships and the strangers on board, “somebody composed a song…while they were still on the ocean. The song says: ‘I got my walls of a house floating on the water.’”

Once Cook and his men had anchored in Resolution Cove, the Mowachaht came near their vessels again and called out “Itchme nutka! Itchme nutka!” urging them to go around Bligh Island and anchor at Yuquot, later known as Friendly Cove. Not knowing that the word nutka means “go around,” Cook assumed the men were indicating their name or the name of the place. Both became known as “Nootka” in subsequent years, and for many years the term “Nootka” came to include all of Vancouver Island’s west coast peoples, as well as their linguistic group.

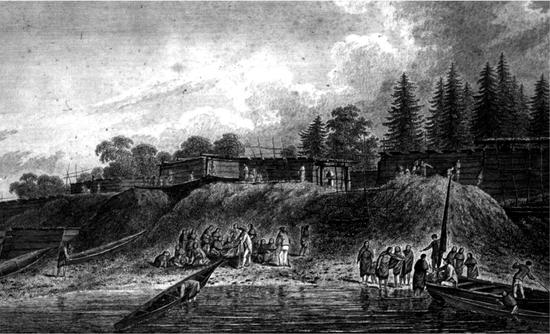

For the following month Cook’s men cut trees for masts, brewed spruce beer, and traded with the Indigenous people and their powerful chief, Maquinna, who would later exert immense influence on the sea otter trade. The Mowachaht offered the British various furs for trade, including sea otter pelts, and also carvings, spears, and fish hooks. In exchange they gladly accepted knives, chisels, nails, buttons, and any kind of metal. While repairs continued, Cook explored the rest of Nootka Sound by longboat, stopping at Yuquot where John Webber, his shipboard draughtsman, produced many sketches and watercolours depicting the dwellings, the way of life, and the people.

After almost a month in Nootka Sound, Cook and his men left the area on April 26 and sailed north to Alaska and into the Bering Strait, seeking the elusive Northwest Passage, before heading home via Hawaii. On February 14, 1779, Cook met his death there, on the beach of Kealakekua Bay on the Big Island of Hawaii, while investigating the theft of one of his ship’s boats by Hawaiians. His crew later returned to the beach, collected his dismembered body parts, and, after placing them in a coffin made by the Resolution’s carpenter, consigned him to the deep. The Resolution continued across the Pacific to Canton in China, and there the crew traded 300 sea otter pelts they had acquired at Nootka. These pelts, which the crew had been using as bedding in their hammocks, fetched the staggering sum of 120 Spanish dollars each, more than double the yearly wages for a seaman. They loaded up with porcelain, silks, and spices, and the Resolution continued its circumnavigation of the globe by sailing across the Indian Ocean, round the Cape of Good Hope, and north to Britain. Back in England, they sold the trade items they had purchased in China for profits ranging as high as 1,800 percent. News of such vast profits spread rapidly.

In 1783, John Ledyard, one of the two Americans in Cook’s crew, published his memoir entitled A Journal of Captain Cook’s Last Voyage to the Pacific Ocean, and in Quest of a North-West Passage between Asia and America. In his book, Ledyard described how sea otter pelts, “which did not cost the purchaser six pence sterling, sold in China for one hundred dollars.” The following year the British Admiralty published a heavily edited account of Cook’s voyages in three volumes; the books sold out within days and went into several more editions, followed by translations. As word of Cook’s voyages spread, avid interest in the North Pacific fur trade escalated, spurring British investors to sponsor trading ventures on the Pacific Coast, using Cook’s precise maps and observations. Some of Cook’s officers, Nathaniel Portlock, George Dixon, and James Colnett, recognizing the commercial opportunity in the sea otter fur trade, quit the Royal Navy and formed their own trading company, the King George’s Sound Company, to engage in fur trading in the Pacific Northwest.

The rush for “soft gold” was on. Because sea otters only live in the Pacific Northwest, traders and adventurers targeted this area for decades to come, in a frenzy of trade for the glossy, luxurious furs. With 600,000 hairs per square inch, sea otter pelts have the thickest fur of any mammal. Their unparalleled softness, near-luminous sheen, and immense warmth made them an invaluable commodity. In the peak years of the sea otter trade, from 1790 to 1812, up to two dozen trading vessels plied the coast of what is now British Columbia, taking tens of thousands of sea otter pelts. Farther north, the Russians generally confined their territorial and trade interests to Alaska, where they had first landed in the early 1740s. They established a permanent settlement on Kodiak Island in 1784. In all locations along the coast, as the trade increased, the various First Nations became more experienced at driving hard bargains and more accustomed to European goods, including firearms, alcohol, and foods like molasses and beans. They also became more exposed to disease, particularly syphilis and tuberculosis.

The sea otter trade began in earnest with the voyage of Captain James Hanna. On August 18, 1775, Hanna became the first British commercial trader to reach the West Coast, arriving at Nootka aboard his sixty-ton brig Sea Otter. He had set sail four months earlier with a crew of thirty, leaving from the Portuguese colony of Macao, just south of Hong Kong. Hanna’s voyage received backing from John Henry Cox, a British trader in China, and though he never set foot in BC, Cox Bay near Tofino, and Cox Island, off Cape Scott, bear his name. Hanna traded iron bars for furs at Nootka, returning to China at the end of September with 560 sea otter pelts, which sold in Canton for 20,600 Spanish dollars.

Although Hanna’s trip proved highly successful in commercial terms, it introduced the first bitter note of conflict in relations between traders and Indigenous people on the West Coast. During Hanna’s time in Nootka Sound, he and his crew killed twenty Mowachaht men and a chief as they tried to board the Sea Otter in broad daylight. This confrontation arose either because of a practical joke in which gunpowder exploded under Chief Maquinna’s chair, or because of the theft of a chisel from the Sea Otter. Despite the killings, and possibly because Hanna and his crew took care of the Mowachaht whom they had wounded, he was able to complete his trading and leave with his ship and crew intact.

Different notions of property ownership repeatedly fuelled disagreements between local people and the visiting traders, sometimes with fatal results. Indigenous people generally held to the idea of universal ownership of property, seeing nothing wrong in taking whatever the owner could not protect. Nails, rowboats, tools, and clothing proved fair game, but the traders saw this as theft deserving severe punishment. The coastal people never forgot violent responses, such as the Sea Otter incident, and they could wait a long time for revenge. Nearly twenty years after the unhappy confrontation with Hanna and the loss of so many of his people, Chief Maquinna achieved his revenge when he and his tribe seized the American trading vessel Boston and killed all but two of that ship’s crew.

In 1786, Hanna returned in a larger 120-ton ship, also named Sea Otter, on a voyage financed by the Bengal Fur Society. He found that other traders had already bought most of the available skins at Nootka, so after two weeks there, during which he obtained only fifty pelts, he sailed north to the top of Vancouver Island and then south again into Clayoquot Sound, seeking more furs. At the principal Ahousaht village, then on Vargas Island, he befriended Ahousaht chief Cleaskinah, who subsequently became known as “Captain Hanna” following an exchange of names in accordance with local custom. With this visit, Hanna and his crew became the first Europeans to enter Clayoquot Sound and to trade there. Hanna acquired some furs, although far fewer than on his first voyage, and netted only 8,000 Spanish dollars for his cargo when he returned to Macao in February 1787.

Another private trader arrived on the coast in 1786; Captain James Strange, son of the eminent engraver Sir Robert Strange and godson of James, the Pretender to the Scottish throne. With his crew suffering from scurvy, Strange arrived at Nootka Sound aboard the vessels Captain Cook and Experiment. He remained at Nootka long enough to plant a vegetable garden, and on departing he left his surgeon’s assistant, Irishman John Mackay, with Chief Maquinna. Before joining Strange’s ship, Mackay had served in the British Army in Bombay, and when in Nootka he contracted an illness described as “purple fever,” forcing Strange to leave him at Nootka with a promise to return for him at a later date. Maquinna assured Strange that his doctor “should eat the Choicest Fish the Sound produced; and that on my return, I should find him, as fat as a Whale.” Having equipped Mackay with two goats, some seeds, and a gun, Strange departed, leaving Mackay to become the first European resident of British Columbia. In mid-November 1786, when Strange reached China, he sold his cargo of 600 pelts for 24,000 Spanish dollars.

At Nootka, Mackay endeared himself to Maquinna by curing the chief’s daughter Apenas of a “scabby disease.” Having recovered from his own malady, he settled into life among the Mowachaht, and all went well until he unwittingly broke a local taboo by stepping over a cradle bearing Maquinna’s child, for which he was beaten and banished. Later, when the child died, Maquinna exiled Mackay from his house, forcing him to live on his own. He barely managed to survive, but he did discover the place he resided was not on the continent of America but on a sizable island, something not reliably acknowledged until a decade or more later when Captain Vancouver circumnavigated Vancouver Island in 1792.

As Strange sailed for China, the fourth European nation to take an interest in the Pacific Northwest arrived on the coast, not seeking sea otters, but bent on finding the Northwest Passage. Eager to keep pace with Britain, in 1785 King Louis XVI of France sent Jean-François de La Pérouse with the vessels Boussole and L’Astrolabe on a scientific expedition of discovery in the Pacific Ocean. After visiting Easter Island and Hawaii, La Pérouse arrived off the coast of Alaska on June 23, 1786, and then sailed south, mapping the coast of Haida Gwaii and the west coast of Vancouver Island, continuing until he finally reached Monterey, California. Neither La Pérouse, nor any of his 114-man crew, set foot on British Columbia soil. La Pérouse continued to explore in the Pacific for the next two years. In December 1787, his expedition lost eleven crew and the commander of the Astrolabe, killed by Samoan Islanders, before landing near Botany Bay, Australia, in 1788. After leaving Australia, all members of the expedition died when both ships sank during a violent storm off Vanikoro Island in the Solomon Islands. Offshore from Vancouver Island, La Perouse Bank, famed as the feeding grounds for migrating fur seal, bears the name of this explorer.

In June 1787, Captain Charles William Barkley, aboard the 400-ton Imperial Eagle, arrived at Nootka with his wife, eighteen-year-old Frances Hornby Barkley, the first European woman to visit British Columbia. Imperial Eagle was the largest ship ever to enter Nootka Sound. The size of the ship, along with Frances Barkley’s impressive red-gold hair, left a lasting impression. Barkley sailed under the flag of the Austrian East India Company, trying to avoid the high fees demanded by the large English trading monopolies, the East India Company and the South Sea Company. During their month-long stay at Nootka, the Barkleys met John Mackay, whose facility with the language greatly assisted Barkley in negotiating for pelts. They took Mackay aboard and eventually returned him to the Orient; fortunately for him, as Captain Strange had not returned to pick up Mackay as promised.

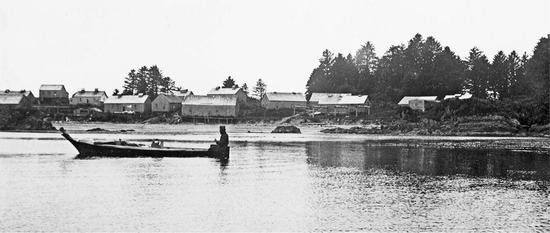

The summer of 1787 also saw the arrival of the Prince of Wales and Princess Royal in Nootka Sound at the same time Barkley’s Imperial Eagle was moored there. The arrival of these ships, belonging to the authorized King George’s Sound Company and commanded by Captains James Colnett and Charles Duncan, forced Barkley to leave because he did not possess proper trading credentials. He sailed south on July 24, 1787, in search of more pelts in less conspicuous territory. Entering Clayoquot Sound, he named it Wickaninnish Sound, after the Tla-o-qui-aht chief. Frances Barkley described the chief vividly in her journal, writing that he “seemed to be quite as powerful as the potentate Maquilla [Maquinna]. Wickaninnish has great authority and this part of the coast proved a rich harvest of furs for us. Likewise, close to the southward of this sound, to which Captain Barkley gave his own name. Several coves and bays and also islands in this sound we named. There was Frances Island, after myself; Hornby peak, also after myself; Cape Beal after our purser.” This visit made Barkley and his crew the second shipload of Europeans to visit Clayoquot Sound.

The Imperial Eagle continued south to Washington State, where a tragic confrontation with Indigenous people left six crew members dead. The ship continued across the Pacific to Macao, where Barkley sold his 800 sea otter pelts for 30,000 Spanish dollars. Barkley then sailed on to Calcutta to outfit the Imperial Eagle for a second voyage to the northwest coast, but his promoters sold his ship and cancelled their contract with the captain. Former Royal Navy lieutenant John Meares acquired Barkley’s navigational instruments and charts from the Imperial Eagle, which he would later use to advantage. According to Frances Barkley, Meares also “with the greatest effrontery” took possession of Barkley’s valuable seafaring journal, later taking credit for and publishing many of Barkley’s achievements as his own.

In 1786, Meares had ventured across the Pacific on his first voyage as a commercial fur trader sponsored by John Henry Cox and the Bengal Fur Society, earlier sponsors of James Hanna. On that voyage, Meares lost twenty of his twenty-nine crew to scurvy and nearly froze to death in Prince William Sound, Alaska. Undaunted by the ravages of his first adventure, Meares once again set out for the northwest coast, now armed with Barkley’s charts and journals, and under the auspices of a new sponsor, the Company of Free Commerce of London. He arrived at Nootka in May 1788, following a nearly four-month voyage from China in the Portuguese-registered Felice Adventurer. On board with him, Meares had twenty-nine Chinese workers, including “seven carpenters, five blacksmiths, five masons, four tailors, four shoemakers, three sailors and one cook.” A handsome, controversial figure, Meares has been variously described as a liar, scallywag, scoundrel, and conniver, the Machiavelli of the maritime fur trade. Historians concur that Meares rarely acted honourably, and Chief Maquinna called the wily trader Aita–aita Meares, meaning “the lying Meares.” During the month of May 1788, which he spent at Friendly Cove, Meares purchased land from Maquinna for “8 to 10 sheets of copper and several other trifling articles.” At this site, he instructed his Chinese workers to build a house, a storehouse, and a ship. When completed, the 40-ton North West America would become the first ship built in British Columbia. Meares intended the ship as a coastal trader, to scour the coast for furs, winter in Hawaii during the stormy months, and return each summer to operate out of a permanent base he planned to establish at Nootka. Leaving his compatriot Captain William Douglas of the Iphigenia Nubiana at Nootka to supervise construction, he set sail in the Felice Adventurer to explore the area to the south.

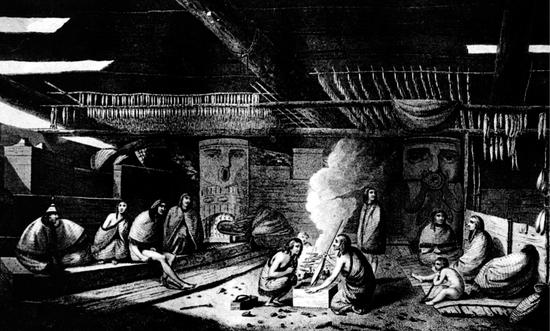

On June 13, 1788, Meares arrived at Echachis, Chief Wickaninnish’s main summer village. Located on a small island in Templar Channel near Wickaninnish Island and just west of MacKenzie Beach, Echachis at the time was a hubbub of activity, as the Tla-o-qui-aht gathered for a special feast. Meares and his men joined 800 other men in Wickaninnish’s longhouse for a welcome feast of boiled whale, while the women watched from the outer fringes.

Meares left behind detailed descriptions of Chief Wickaninnish and of life among the Nuu-chah-nulth, the Tla-o-qui-aht in particular. According to Meares, Wickaninnish held sway over a vast area between the Strait of Juan de Fuca and Woody Point, and although Wickaninnish estimated he had 13,000 subjects, Meares remarked that “we rather think that the chief, either from modesty or ignorance, under-rated the population of his country.” Meares visited Chief Wickaninnish’s principal village of Opitsaht, naming it and the nearby waters Port Cox after his backer. He estimated Opitsaht to be “three times the size of Maquinna’s Yuquot, with a population of about four thousand inhabitants.” There lived the chief “in a state of magnificence much superior to any of his neighbours, both loved and dreaded by other chiefs.” Meares described Wickaninnish to be in his early forties, reputedly with ten wives, and “rather inclined to be corpulent…athletic and active.” In Meares’s estimation, Wickaninnish equalled Chief Maquinna in power, and only the fact that Maquinna’s favourite wife came from Wickaninnish’s family kept the two tribes in a state of relative peace.

Having noted that the Tla-o-qui-aht women were “very superior in personal charm to the ladies of Nootka,” Meares traded for 150 otter skins and presented Wickaninnish with many gifts, including “six brass-hilted swords, a pair of pistols, and a musket and powder.” He then set off south as far as Juan de Fuca Strait before returning north again. As he neared Nootka, Meares encountered Captain Charles Duncan and his fifteen-man crew on the 65-ton Princess Royal sailing southward into Clayoquot Sound. Duncan and his companion James Colnett had spent the spring and summer exploring and trading in and around Haida Gwaii, and now Duncan intended to visit Ahousaht to top up his cargo of furs before sailing on to Hawaii to winter. Meares stayed at Nootka until September 24, 1788. By then he had squelched the second mutiny of this voyage among his men, launched the North West America on September 20, and loaded his ships with furs, spars, and masts. Meares well realized the vast potential of the coastal timber, knowing Europe’s shipbuilding timber to be all but depleted. “The woods of this part of America are capable of supplying…all the navies of Europe,” he wrote.

Just a week prior to Meares’s departure, on September 16, American captain Robert Gray, in the 90-ton sloop Lady Washington with a crew of nine, arrived at Nootka. Seven days later his compatriot and commander, Captain John Kendrick, arrived in the 212-ton Columbia Rediviva with a crew of thirty-nine. While rounding Cape Horn the two ships became separated but they eventually reunited, and their arrival on the West Coast opened a new chapter in the Pacific maritime fur trade. The introduction of the Americans into this highly controlled and jealously monitored trade ultimately broke the monopoly held by the East India Company and other British-owned companies. The Americans, or “Boston Men” as the coastal peoples called them, would become the dominant players in the sea otter trade on the coast.

During this early period of exploration and trade on the northwest coast, most of the explorers and traders dealt with the local people in a fair and respectful manner. “King George’s” captains, such as James Cook and later George Vancouver, were under orders to explore this territory and negotiate with the Indigenous people in a decorous manner. Not so the Americans. Motivated by quick profit, they treated the local people in an entirely different way, leading to dire consequences for both sides.