Chapter 7: The Sealing Years

The Nuu-chah-nulth always knew of the vast numbers of northern fur seals (Callorhinus ursinus) migrating offshore every spring as they travelled north from California to their breeding grounds in the Pribilof Islands in the Bering Sea. Highly skilled seal hunters all along the coast prided themselves on their prowess at locating and harpooning these seals, and because these northern fur seals never approached the shore, the hunters paddled far out to sea to find them. For Nuu-chah-nulth hunters, the shallow waters of La Pérouse Bank, some sixty kilometres offshore from Barkley Sound, always provided the best hunting ground. In this area, rich in marine life, the seals stopped to feed and rest.

This seal hunt had been significant for centuries; recent evidence from middens at Hesquiaht and elsewhere on the west coast indicates that the Nuu-chah-nulth harvested far more northern fur seals than other mammals such as sea lions, porpoises, or harbour seals. As William Banfield noted in 1858, “The flesh they eat, and deem it quite a luxury.” Yet despite this long history of traditional use, no significant trade in seal skins existed on the west coast of Vancouver Island until the mid-nineteenth century. European traders in this area focused on the immensely valuable sea otter pelts, but after the sea otter population dwindled to almost nothing, the fur seal hunt off Vancouver Island’s west coast gradually gained momentum. By the 1860s these seals had dramatically increased in number, the population having been seriously threatened in earlier years by the Russians’ extensive fur seal hunt off Alaska.

In 1786, Russian captain Gerassim Pribilof, working for an early Russian fur trading company in the Aleutians, discovered the location of the northern fur seal rookeries on the islands in the Bering Sea that now bear his name. For nearly two decades following his discovery, Russian hunters indiscriminately slaughtered untold millions of these animals in their rookeries. Eventually the Russian government realized that the uncontrolled hunt could destroy the lucrative sealing industry and took action to protect the seals from extinction. It banned sealing entirely for four years, from 1804 to 1808, and imposed rigorous quotas for many years following the ban. These closely enforced restrictions allowed the fur seal population to recover to the point that by 1867, when Russia sold Alaska to the United States for $7.2 million, the Pribilof Islands hosted an estimated two million seals on a total land area of under 260 square kilometres. The increased numbers of fur seals at the rookeries meant they reappeared in great numbers off the coast of Vancouver Island on their migration north. Beginning in December, and for the following five or six months, year after year, a massive host of fur seals journeyed along the outer coast, past Clayoquot Sound and beyond Haida Gwaii, heading for the Pribilof Islands.

Independent traders making their way up and down the outer coast of Vancouver Island became increasingly aware of this immense migration and of the expanding potential of the sealskin trade. The trade developed gradually, with the Haida starting to hunt seal for their pelts, rather than only for meat, in the late 1840s. By 1858, William Banfield observed that the Tseshahts of Barkley Sound had “developed a healthy trade in seal skins.” The skins were avidly sought for making sealskin coats; with 300,000 hairs per square inch (half that of the sea otter), they provided one of the richest pelts available.

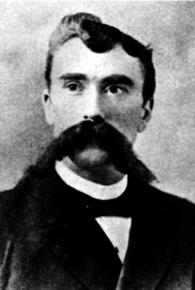

Coastal trader Captain William Spring, highly influential in the fur seal industry, began trading at Kyuquot, taking over from William Banfield, who had been mysteriously murdered in 1862 in Barkley Sound. Spring worked in partnership with Scottish cooper Hugh McKay, and they traded for seal skins, which, along with dogfish oil, they took to Victoria and sold to the Hudson’s Bay Company. Spring and McKay also cured salmon for sale to Hawaii. Within a few years, Spring’s interest in the fur seal hunt on the coast of Vancouver Island led to an innovative practice that transformed the hunt completely.

Born in Russia in 1831 to a Scottish engineer and his Russian wife, Spring had arrived in Victoria in 1853, aged twenty-two. He entered the partnership with Hugh McKay, who had arrived in Victoria five years earlier, and together they started in business in 1856 with their vessels Ino and Morning Star, running freight to the Olympic Peninsula and trading around southern Vancouver Island. Morning Star foundered off Discovery Island in 1859, to be replaced by the schooner Surprise. By 1864 another schooner, Alert, had joined their small fleet, later followed by the stalwart Favorite. For many years these vessels plied the coastal waters from Washington State up to Alaska, becoming especially known for their role in sealing.

Through his trading ventures, Spring began to consider how best to maximize the potential profit of the fur seal trade. In 1868 he came up with a new idea. Knowing the dangers faced by Indigenous hunters who paddled up to fifty or sixty kilometres offshore in their small canoes to hunt the fur seals in their feeding grounds, he decided to take the hunters to the seals. He ordered Captain James Christensen of the Surprise to take twelve Tla-o-qui-aht hunters and four canoes out to La Pérouse Bank. After three days of hunting, the expedition netted only twenty-seven skins; Spring’s schooner kept nine pelts, and the Tla-o-qui-ahts eighteen. Two of their canoes and six hunters were lost in fog, but when Surprise returned to Clayoquot Sound the crew discovered the lost hunters had made their way safely back to shore on their own.

This voyage, unpromising though it seemed at the time, marked the beginning of the Victoria-based pelagic, or open ocean, seal hunt. Over the next forty-seven years, this became a massive international business involving Russia, Japan, Great Britain, Canada, and the United States. The industry made the city of Victoria and the province of British Columbia economically stable; transformed the First Nations economy on the west coast, changing it from a system based on trade to one based on currency; and eventually reduced the fur seal populations from an estimated five million in 1864 to 123,000 by 1911.

In 1869, despite the meagre catch on that first pelagic sealing venture, Spring sent Captain Peter Francis out to La Pérouse Bank to try again. With him aboard the schooner Alert, Francis had twelve Ucluelet hunters and their canoes. This time the returns could not have been better, and the crew salted down 900 skins for Francis to take back to Victoria. The west coast fur seal industry suddenly became viable.

By 1876, nine sealing schooners based out of Victoria took Nuu-chah-nulth hunters and their canoes to the sealing grounds. Five of these ships were owned by Captain Spring and his growing number of partners. By 1882, fourteen schooners engaged in this pelagic hunt. That year, sealing captains spent $200,000 on wages and supplies in Victoria, hired as many as 400 Indigenous hunters in a season, and paid them from $2 to $4 a pelt, good money in those times. The numbers of schooners continued to rise, and by the end of the nineteenth century, over seventy sealing schooners, many from San Francisco, could be found anchored in Victoria.

Typical of these schooners, the 120-ton, 27-metre-long, 7-metre-wide, double-masted Favorite often frequented Clayoquot Sound during the sealing era. Like so many other schooners, she sailed into the Sound to recruit Tla-o-qui-aht, Ahousaht, and Hesquiaht seal hunters, known to be the best on the coast. Built in 1868 at Sooke for Captain Hugh McKay from Douglas fir cut in the Sooke hills, the Favorite could carry a massive 400 square metres of sail.

In July 1868, McKay, then in partnership with Captain William Spring, sailed the Favorite to Hawaii with 120 tons of mixed cargo. Upon his return two months later, he began using the schooner on the west coast as a trading vessel. After seven years at the helm, McKay sold the ship to Spring and his new partner, Peter Francis, and Favorite became more heavily involved in the sealing trade. Father Augustin Brabant frequently found himself a passenger aboard the ship on his trips to Victoria and around the Sound. In 1885 she carried much-needed medicine to Hesquiaht during an outbreak of measles and smallpox. On another trip she carried a new bell for the Hesquiaht church, which the crew helped install; legendary sealing captain Alex MacLean rang this bell for the first time. In 1888, on a government contract, she carried lumber to build housing in First Nations settlements. The bricks found today in the church at Friendly Cove arrived, along with the lumber, aboard Favorite. This schooner lived out her days in Clayoquot Sound; today her hulk lies at the bottom of a small cove at the head of Holmes Inlet.

When schooners such as Favorite arrived in Clayoquot Sound, their captains sought out the best Indigenous hunters and, with the help of local middlemen like Fred Thornberg, Walter Dawley, and John Grice, signed them on for the hunt. Hiring took place only after their chief had negotiated a price for each seal caught. Then the hunters loaded their dugout canoes onto the schooner; a dozen and more canoes could be stacked on the decks of the larger vessels, which could carry up to thirty hunters. Sometimes women accompanied their husbands on the seal hunt, handling the canoes and participating skillfully in the hunt. Once at the sealing grounds, the chief hunter, who acted as “boss” for the others on board, would judge the weather and the wind, deciding when to launch the canoes. Crewed by a harpooner and a paddler or steersman, the canoes would be dropped from the mother ship at daybreak to begin searching for and hunting seals.

The fur seals fed at night and slept at the surface during the day. Their keen sense of smell meant they could detect predators from two kilometres away, so the hunters cautiously approached the seals downwind. The steerer brought the canoe to within ten metres of a seal, and the harpooner grasped his weapon, a wooden shaft with two detachable spearheads attached to prongs at the leading edge. Holding the harpoon in two hands, he hurled it at the seal’s head. The hunters always aimed near the head to avoid putting a hole in the skin, hoping for an unblemished pelt.

Once the seal had been harpooned, the shaft of the harpoon detached from the spearheads and floated on the surface; tied to the canoe by a four-metre-long cod-line, it was easily recovered later. Without the heavy wooden shaft, the harpooner was more easily able to play the seal, just as a fisherman would play a large fish. After the fight, which might take from five minutes to several hours depending on the size and strength of the seal and on how well, and where, the spearheads had embedded, the harpooner drew the seal to the side of the canoe, where he dispatched it with a blow to the head.

Using this method, hunters rarely lost a seal because the harpooned animal remained attached to the canoe by lines and floats. When both Indigenous and European hunters began to use guns, many seals were lost, their bodies sinking before they could be recovered. Estimates reveal that three seals were often lost for every one collected, and sometimes the ratio was far higher; in 1882, 100,000 seals were killed in order to obtain only 15,000.

Sometimes two or more canoes would raft together for stability, and the steerers would pull the dead seals aboard and skin them on the spot, allowing the carcasses to drop into the sea. Sometimes, if the kill happened near the mother ship, they would skin the seals on the schooner and retain the meat and blubber. Manhandling these carcasses required strength and good balance: a large male could measure over two metres long and weigh over 360 kilograms; the much smaller females weighed only around 50 kilograms. The hunting and skinning continued until nightfall, when the canoes returned to the mother ship, where the crew laid the skins flat and salted them down in the ship’s hold. When the skins eventually reached Victoria, where servicing the sealing industry played a major part in the economy of the young city, handlers rolled them in salt and packed them into barrels for shipment to C.M. Lampson, the company in London, England, that processed the fur seal pelts. There, processors dyed the skins—if it was not dyed, the skin looked decidedly unappealing—and cured them. Following processing, Lampson auctioned off the skins, most of which became coats. Five skins made one coat, which sold for a little over $100. At the height of the industry, more than 10,000 people in England found employment processing fur seal pelts.

Pelagic sealing off the coast of Vancouver Island served both the Nuu-chah-nulth hunters and the early schooner owners well. The hunt took place within the local people’s traditional seal hunting season, before the halibut fishing season began, and during a slack time for the schooners, which usually did their trading cruises to collect dogfish oil in the autumn months. The Indigenous “boss,” who received a bonus for his role on the schooner, worked collaboratively with the captain on daily decision making. The schooners returned to the hunters’ home villages every five or so days to dry the seal meat, a delicacy more valued by coastal people than the skins. They would also return to shore when storms made hunting dangerous.

Even while this offshore, schooner-based sealing took place, Indigenous hunters carried on independently, hunting seals and selling skins to nearby trading posts, or taking them to Victoria by canoe for sale. According to Peter Murray in his book The Vagabond Fleet, in 1880 a total of 900 pelts from shore-based seal hunters at Hesquiaht netted $30,000, making some hunters as much as $120 a day. With returns of this magnitude, the once lucrative dogfish oil trade suffered. Father Brabant wrote in 1882: “Two years ago I persuaded the young men to try their luck as fur seal hunters. From the beginning, their success was such that they now seem to be determined to prosecute this lucrative work and leave the dog fish business to the old people.”

In 1882, sealing schooner captains began following the fur seals up to Alaska and to the Pribilof Islands, taking their crews much further afield. Many more problems and dangers now presented themselves to the schooners and to their hunters. Until this point, the seal hunt had taken place between January and June, within reasonable distance of Vancouver Island—never more than a couple of days away. When the hunt extended up to the Bering Sea, it began in July and ended in October, taking hunters away from their villages for months at a time, cutting into the fall salmon fishing season, and interfering with the centuries-old rhythm of the Nuu-chah-nulth calendar.

In 1884, Brabant wrote of the first Hesquiaht crews going up to the Bering Sea. “Last June seventy young men went on the sealing expedition to the Bering Sea. They did very well and arrived home highly delighted with the success of their long voyage. They killed 1400 animals, receiving two dollars per animal.” By 1885, the harpooners from Kyuquot thought that they had become so indispensible that they demanded $5 a skin from the schooner owners, refusing to sign on until they got their price. Unable to find crews, the owners eventually settled on $4 a skin. As time passed, prices mounted; by 1907, traders were paying hunters $8 a skin as the price of seal skins increased on the international market.

The rising prices of seal skins encouraged Indigenous hunters to take up shore-based sealing, making it more difficult for the captains of pelagic schooners to sign the best hunters. Agents and middlemen, often traders along the coast, took an ever more active role on behalf of the schooner owners, trying to secure the best hunters. These middlemen would start bargaining months before the sealing season began, at a time when hunters needed money, paying them advances on their potential earnings as early as January, well ahead of the Bering Sea hunt that began in June. But by the late 1870s, salmon canneries along the coast, along with hop farms in the Fraser Valley, also vied to attract Indigenous workers, and those industries provided accommodation for entire families. Many chose these forms of employment because they could preserve the family structure, rather than having men leave their villages and families for months at a time to go sealing.

In 1897, some of the sealing captains became so frustrated dealing with the hard-bargaining Nuu-chah-nulth hunters that Captain Sprott Balcom, later a prominent figure in the West Coast whaling industry, floated the idea of bringing Micmac hunters from Nova Scotia to take their place. “The Indians of the West Coast will not be so independent in their dealings with the white skippers; incentives for good work will be developed; and our own Siwashes will find in the Micmac’s industry an object lesson,” observed the British Colonist on January 16, 1897. Balcom proposed locating the Micmacs on an unnamed island comprising “5 to 600 acres [200 to 245 hectares] of arable land somewhere between Clayoquot and Ahousaht,” suggesting “the Indians [Micmacs] be hired at wages that would astonish the west coasters.” The unlikely idea also recommended that the Micmacs bring birchbark with them so they could construct canoes and dwelling huts when they arrived. Nothing came of this scheme.

In many of his letters, Ahousaht trader Fred Thornberg described striking bargains with seal hunters on behalf of schooner captains. Always a contrarian business, this became far more complex when several schooners showed up at the same time in the villages, squaring off to obtain hunters. Walter Dawley, at the Clayoquot trading post, received a constant stream of letters from anxious sealing captains, who wrote to ask for advice, intervention, or special treatment in finding hunters. In 1899, Captain H.F. Sieward announced, “I have secured 13 canoes try and secure me Kelsamat Jack…get him somehow but get him…clinch him with an advance.” In another letter, Sieward foresaw trouble, writing, “I am afraid that with 3 schooners…there will be a hot time in Ahousat,” while Captain J.W. Peppett braced himself for an enjoyable scrap at the village: “If I am obliged to make a fight for hunters, I want to be in the hottest part of the fight.” The scene of the fiercest competition always tended to be Ahousaht, but all along the coast small conspiracies and shifting allegiances among the captains, hunters, and middlemen made for continual deal making and breaking. The more determined of the seal hunters would head down to Victoria to bargain directly with the captains, cutting out the middlemen and striking deals on behalf of a group of hunters, much to the chagrin of the sealing companies. William Munsie, head of the Victoria Sealing Company, wrote angrily to Walter Dawley more than once, reporting that hunters had been striking their own deals in the city and demanding that Dawley keep them in their villages.

By no means all of the Nuu-chah-nulth seal hunters attempted such assertive bargaining, most being content to let the “boss” of their crew negotiate. The type of conflict experienced at Ahousaht did not arise to the same extent in other locations in Clayoquot Sound. At Opitsaht, Chief Joseph appears to have been influential in keeping the peace between his Tla-o-qui-aht hunters and the sealing captains. Renowned as a whaler in his youth and as an extraordinary canoeman, Chief Joseph made several trips to the Bering Sea aboard schooners, and the sealing captains “bid high for his services,” according to George Nicholson in a Daily Colonist article. Held in high esteem by his own people and by the white community, Chief Joseph arbitrated disputes of any kind with a firm hand. His wife, who spent several seasons on sealing vessels as a cook, became known as “Queen Mary,” a name probably given to her by a sealing captain. The couple lived to a great age, in later years easily spotted paddling every day from Opitsaht to Clayoquot, where they found a warm welcome from the storekeeper.

Whether shore-based or pelagic, sealing presented many dangers and at times led to loss of life. In May 1875, over a hundred shore-based Nuu-chah-nulth seal hunters, in seventy canoes, died in a sudden storm that carried some of them as far southwest as the Washington coast; this incident made it easier for the schooners to recruit hunters. The single most tragic event affecting hunters from Clayoquot Sound occurred twelve years later, on April 1, 1887. The schooner Active sank in a storm off Cape Flattery, claiming the lives of twenty-four Kelsemaht hunters from Yarksis on Vargas Island. The tragedy left nineteen widows and forty-two orphans destitute, and it devastated the relatively small Kelsemaht band, nearly wiping out its male population. Five others also died aboard the Active, including one of the vessel’s owners, Jacob Gutman, at the time co-owner of the Clayoquot trading post along with partner Alexander Frank. Gutman had employed Fred Thornberg to run the operation there, and because Thornberg had hired their fellow tribesmen to go on board, many Kelsemahts blamed him for all the deaths. Seeking vengeance, two Kelsemahts broke into the Clayoquot trading post; “bothe had a very wild look on their face…they could hardly speak,” Fred Thornberg wrote. He managed to appease the men with tobacco and matches, promising that with the help of the Indian Department and the Catholic priest he would arrange relief for the families of the lost men. Thornberg later wrote, rather sadly, “If I had not askt them to goe sealing they would not be drownet & lost.”

As the Bering Sea fur seal hunt continued, serious and lengthy jurisdictional disputes surfaced. In 1867, the United States had purchased Alaska from Russia, partly to secure the fur seal rookeries of the Pribilof Islands. The United States did not want foreign competition in this area, and in 1881 it declared that all fisheries, including the one for fur seals, whether on land or sea, stretching from the coast of Alaska to the International Date Line, were American property. To enforce this edict, the United States dispatched gunboats to the North Pacific to protect its interests. Before long, those gunboats began seizing any foreign schooner in the Bering Sea that had guns, harpoons, or seal skins aboard. The seizures occurred up to a hundred kilometres offshore, at a time when five kilometres (three miles) was considered the limit of a country’s territorial waters. The gunboats arrested crews and escorted them to Alaskan ports, where their harvest of pelts, and the schooners themselves, faced impoundment. The Indigenous hunters on board sometimes suffered a worse fate, with the Americans seizing their canoes and gear and often marooning them on islands, or setting them adrift in their canoes. Many died of exposure. The Russians and the Japanese, who also controlled islands in the North Pacific where fur seals bred, conducted similar seizures and arrests. The hunt became an international jousting match.

Right from the beginning of fur sealing on the west coast, the schooner Favorite played a role. In 1883, then still owned by William Spring, Favorite came under the command of a new captain, Cape Breton-born Alex MacLean. MacLean’s fame, and that of his brother Dan, also a sealing captain, reached legendary proportions all along the Pacific Coast from Alaska to Mexico. In his 1904 novel The Sea-Wolf, novelist Jack London based his villainous character Captain Wolf Larsen on the larger-than-life exploits of Alex MacLean, while Dan served as the model for Wolf’s fearsome brother Death Larsen. This brought them even greater renown, but the MacLeans resented the comparison, for although hard men at sea, and harsh with their crews, their behaviour had nothing in common with the murderous, half-mad Larsens.

In 1885 the two brothers launched “the MacLean experiment.” Dan captained the schooner Mary Ellen with a European crew on board, and Alex went out in Favorite with seventeen Hesquiahts and three Tla-o-qui-ahts. They set out to determine whether Europeans using guns or Nuu-chah-nulth using harpoons would prove the most profitable. From January until August the two schooners plied the waters of the Bering Sea, hunting seals. Dan’s Mary Ellen acquired 2,309 skins and Alex’s Favorite 2,073. Yet while Dan MacLean may have beaten his younger brother, he needed the extra profit of Mary Ellen’s catch to offset the higher costs of his European crew: feeding a white crew doubled the cost of provisioning a schooner. The Indigenous crew lived chiefly on seal meat and hard biscuit. In the end, the MacLean experiment proved inconclusive.

On that same voyage, two hunters on the Favorite arrived home in Clayoquot Sound by a curious route. Separated from the mother ship while hunting in the treacherous and foggy seas off the Aleutians, the two men eventually reached a local trading post. The storekeeper provided them with food and directed them to a nearby settlement, where they were put aboard a steamer bound for San Francisco. After being treated well by the captain and crew, they arrived at San Francisco, where the British consul paid their passage back to Hesquiaht, via Victoria. Father Brabant reported that “they arrived home last Sunday, just in time to attend Mass. They now excite the wonder of all the Indians.”

In 1886, Dan MacLean returned from the Bering Sea with a record 4,256 skins on the Mary Ellen, allowing him to affix a broom to his masthead signifying a “clean sweep” of honour for the season. Alex MacLean in Favorite returned to Victoria with 3,325 skins. The brothers’ joint earnings that season exceeded $60,000; in today’s terms this would amount to around $1.5 million. Between them, the MacLeans dominated the sealing industry, renowned not only for the number of skins they caught, but also for their cunning avoidance of authorities in the Bering Sea. In 1886, American authorities seized several Canadian schooners—but not those of the wily MacLeans.

Much of the success or failure of sealing depended on the skill and guile of the sealing captain, and on his ability to keep out of harm’s way. Dodging international patrol vessels in the North Pacific waters became an essential skill, and luck also played a part. In 1893, storms in the Bering Sea blew Captain George Heater’s sailing schooner, Ainoko, into restricted Japanese–Russian sealing grounds. While he was trying to leave the area, a Russian gunship overtook the schooner and arrested Heater, seizing his ship, his papers, and his navigation instruments, and ordering him to follow the gunship into Yokohama to face trial. When his fifteen Hesquiaht hunters noticed the schooner was heading west instead of east, they threatened to mutiny. Heater, realizing they outnumbered him and his crew three to one, chose to make a run from the Russians rather than risk an uprising from the Hesquiahts. The Ainoko escaped under cover of fog, and once out of sight of the Russians sailed 4,800 kilometres back to Vancouver Island, without navigational instruments. Heater dropped his Hesquiaht crew at their village and sailed on to Victoria. A court later cleared Heater of hunting within the restricted territory.

Captain Alex MacLean managed to avoid capture by American authorities for many years, but in 1894 his luck ran out. Men from the US revenue cutter Mohican boarded the Favorite and, after finding an innocuous flare gun, seized the schooner and its 1,247 pelts. This seizure led the British government, representing Canada, to protest to the United States, defending the Favorite and other Victoria-based schooners faced with similar problems. In 1897, that protest ended with the American government paying just over $250,000 compensation to Canadian owners of sealing schooners for loss of livelihood and illegal arrest.

The year of MacLean’s capture proved to be a turning point in the industry and in the fortunes of the Nuu-chah-nulth hunters. Tensions between the pelagic sealers and the American, Japanese, and Russian rookery owners led to the closure of the Bering Sea hunt during the 1892 and 1893 seasons. Following arbitration hearings involving the British and American governments, new restrictions banned the use of guns in Alaskan waters. This edict made the Nuu-chah-nulth hunters, because of their harpooning skills, even more important. By 1899 the Nuu-chah-nulth comprised fully 88 percent of the hunters in the fur seal industry.

All the while, as the hunt accelerated, the seal population shrank. Alarm bells sounded about this for many years, from the mid-1880s onward, with fisheries inspectors, scientists, and politicians all asking how the seal population could survive. Between 1872 and 1891 an estimated million and a half seals were killed, including unborn seals in slaughtered females and abandoned pups in the rookeries. By 1910 the fur seal population had been reduced to fewer than 125,000 animals from its former millions. Urgent questions arose about the future of the seal population even as complex attempts to regulate the hunt failed and international bickering became ever more acrimonious. For many years, rumours about the imminent collapse of the entire industry circulated, and wily investors began buying up disused sealing schooners in hopes of receiving future compensation from the government for loss of livelihood. In 1909, negotiations to preserve the seal population began in earnest among the four sealing nations, with a view to establishing an international moratorium on pelagic sealing in the Bering Sea.

In the years leading up to this, a diehard coterie of schooner captains refused to believe their industry would ever cease. Despite their diminished catches, they continued doggedly heading up to the Bering Sea in search of a disappearing species. But fewer and fewer schooners made the journey, the number dropping every year during the first decade of the twentieth century. Embittered and threatened, the captains rancorously blamed their crews, each other, or the government for the hard times facing the industry, and they seized hopefully on scraps of good news. Hearts lifted briefly in 1908 when Thomas Stockham’s schooner Thomas Bayard returned from the Bering Sea with over 600 seal skins and 28 sea otter pelts. Nonetheless, only a handful of schooners went out from Victoria in 1909, and even fewer the next year. Against all odds, veteran captain George Heater managed to obtain 878 seal skins in 1910, and Captain Peppett made his final trip that year also.

In 1911, after prolonged discussions, Japan, Russia, Britain, and the United States signed the North Pacific Fur Seal Convention on July 7, halting commercial pelagic sealing for fifteen years. Victoria schooner owners and their crews, including 861 Indigenous hunters, responded by making individual claims to a royal commission established by the Canadian government, seeking compensation for loss of income. Some of the Indigenous hunters claimed they had made up to $500 per season. In 1916, after sitting for 120 days, the commission presented its report, awarding the 1,605 claimants a total of $60,663. Collectively, they had sought a little over $9 million. The Nuu-chah-nulth received a total of $15,240, the largest single award being $230. As a concession, the North Pacific Fur Seal Convention allowed Indigenous sealers to continue hunting seals using their traditional harpooning methods from canoes, but even that privilege ended in the 1940s.

Most of the Canadian-based sealing fleet was sold for a pittance, some schooners bringing as little as $150 to $200. Many spent their last days slowly rotting at anchor in Victoria harbour; a few were refitted and became rum-runners in the 1920s, carrying liquor from Canada to the United States during prohibition. According to Patrick Lane in his article “The Great Pacific Sealhunt” (published in Raincoast Chronicles 4), the pelagic sealing industry employed 1,400 Caucasians and 1,700 Indigenous hunters on 122 schooners; 15,000 people depended on this industry all along the coast from California to Alaska, and it played a crucial role in the history and economy of northwest North America. The Victoria-based sealing industry earned $1.5 million a year, a huge economic boon to the city, and in 1894, at the height of the industry, Victoria’s harbour bristled with the masts of over 100 schooners, comprising four-fifths of the entire northwest sealing fleet.

For many years these vessels brought trade, excitement, employment, and a great deal of money into villages and trading posts along Vancouver Island’s west coast. Each ship calling at the villages of Clayoquot Sound—Favorite, Surprise, Alert, Umbrina, Mary Ellen, to name only a few—had its own personality, and most had colourful characters at the helm. In their heyday, these schooners carried with them a sense of adventure and potential danger, as well as the possibility of large gains for everyone involved. When the west coast of Vancouver Island started to open up for business in the late nineteenth century, the sealing schooners, more than anything else, made that happen.