Chapter 11: The Hopeful Coast

The summer of 1895 found Victoria-based surveyor Mr. T.S. Gore slogging his way through the bush on the Esowista Peninsula, survey gear and notebook at the ready. As he and his crew beat their way through thickets of salal and salmonberry, trudged through swamps, navigated gullies and deadfalls, and endured clouds of mosquitoes, they took sightings and measurements and blazed perimeter marks onto trees. By the autumn, when Gore had finished, almost all the land from the northern tip of the Esowista Peninsula right down to Ucluelet had been officially surveyed and given lot numbers. The numbers Gore gave the parcels of land he surveyed in 1895 are still used today.

Gore’s field books describe in precise detail every feature of the land, the shores, and the waterways, including the size, type, and density of timber on the land. The few existing structures on the peninsula also appear on his intricate maps, including the new cannery on land pre-empted in 1894 by the Clayoquot Fishing and Trading Co. at the mouth of the Kennedy River, the new sawmill belonging to Thomas Wingen and Bernt Auseth in Mud Bay (now Grice Bay; called Mill Bay by Gore), and the dike under construction at Jens Jensen’s place, in Jensen Bay. Out at Long Bay (Long Beach), Gore’s map of Lot 162 even includes “Dawley’s potatoe patch,” planted on land Walter Dawley pre-empted the previous year.

Following Gore’s survey, the lands on the Esowista Peninsula officially stood open to settlement and development. All this took place with scant, if any, reference to the local First Nations. In the mid-1880s, the government had established the extremely limited reserve lands for Indigenous people living in Clayoquot Sound (the establishment of Indian reserves is covered in Chapter 12). By assigning these reserves, the government had, in its own estimation, “given” sufficient lands to the Indigenous inhabitants; the rest of the land now could be inhabited by newcomers or earmarked for resource exploitation. As the late nineteenth century gave way to the twentieth, Indigenous chiefs and leaders watched with growing concern and perplexity as more and more settlers arrived in their traditional territories, intending to stay. Speaking in 1914, nearly a generation after the earliest wave of settlement, Chief Jimmy Jim of Ahousaht stated: “Some white men have 200 acres [81 hectares] or more, and some have 80 acres [32.4 hectares]. And why have we such a small place here? We were born here, and white settlers have a bigger place.”

The parcels of land surveyed by Gore ranged in size from sixteen to eighty hectares. These could be “taken up” as pre-emptions, timber licences, or mining properties, or they could be purchased outright. To obtain a Crown grant for their land, pre-emptors had to satisfy the authorities and “improve” the land, by building a dwelling, adding fencing, and attempting some form of agriculture—hence “Dawley’s potatoe patch.” While they were expected to live on the land they had pre-empted, many pre-emptors did not do so. They had little interest in agriculture, making half-hearted efforts while pursuing other interests such as handlogging, prospecting, or establishing businesses. Many pre-emptors, throughout the province, did not bother even with token gestures of “improvement,” and their lands reverted to the Crown.

A number of highly significant parcels of land in the Tofino/Ucluelet area had been pre-empted, purchased, or acquired as timber licences before Gore’s survey. William Sutton, of Sutton Lumber in Ucluelet, took up immense tracts of land around Kennedy Lake, Toquart Bay, and Ucluelet Arm in the early 1890s, a prelude to further land acquisitions by Sutton in Clayoquot Sound in the early 1900s. Many decades later, the fate of much of that land, including the original Sutton timber licences on Meares Island, would ignite intense controversy about logging practices. Nearer to Long Beach, the earliest pre-emption occurred in 1890 when James Goldstraw staked forty-eight hectares of land in Schooner Cove. The following year, George Maltby and William Kershaw took up parcels of land adjacent to Goldstraw’s. In 1894, Jacob Arnet, Bernt Auseth, and Thomas Wingen pre-empted land in Mud (Grice) Bay, along with Jens Jensen, in Jensen Bay. Also in 1894, Thomas Stockham took on the island bearing his name in Tofino Harbour, and Walter Dawley pre-empted land at Schooner Cove.

In the Tofino area, settler John Grice registered his strategic pre-emption on May 1, 1893: Lot 114, described in land records as “Low Pen, Hd of” (the Esowista Peninsula appears as “Low Peninsula” on early maps, a name used off and on until the early 1920s), encompassed the northwestern tip of the peninsula, an area of eighty-three hectares. Abutting his pre-emption to the east and south, the adjacent Lot 115 appears on Gore’s survey map as “Low’s Pre-emption.” Little is known of Mr. Low. He did not hold the land long, nor is his pre-emption properly registered, and Gore’s reference to his pre-emption is one of the few solid pieces of evidence about him. In 1896, John Eik and fellow Norwegian Svert Huseby took over Low’s property, eventually receiving a Crown grant for it in 1908. These two parcels of land, Lots 114 and 115, account for the present-day town centre of Tofino.

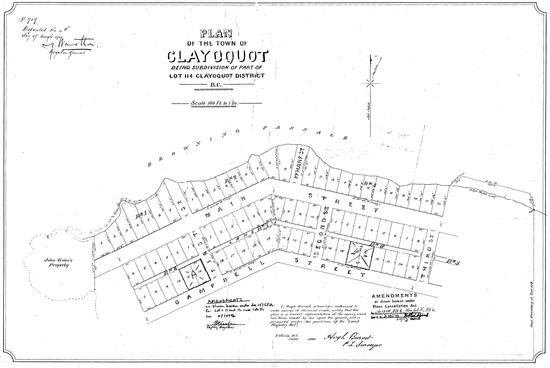

When John Grice acquired Lot 114 with its commanding view of Tofino Harbour, he sensed right away he had a superb property with future prospects. Only seven years later, in 1900, he had this land surveyed and subdivided into lots for a future townsite. At the time, this scheme for a town on the Esowista Peninsula seemed wildly optimistic, given the few settlers, the isolated setting, and the existing settlement just across the water at Clayoquot on Stubbs Island. Yet this type of optimism fuelled the schemes and dreams of countless settlers in British Columbia as they travelled hopefully to distant places, doggedly determined to establish themselves and to make good.

The survey map for Grice’s Lot 114 identifies the proposed settlement as “the town of Clayoquot.” His choice of name added to a confusion of “Clayoquots” that persisted for a number of years, with the name variously used for the community on Stubbs Island, for Stubbs Island itself, for the emerging townsite on the peninsula, sometimes for the village of Opitsat, often for the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation, and more generally for the whole of the Sound. In 1904, Father Charles Moser, the Roman Catholic missionary at Opitsaht, first used the name “Tofino” in his diary, referring to the peninsula townsite. This is one of the earliest known uses of the name.

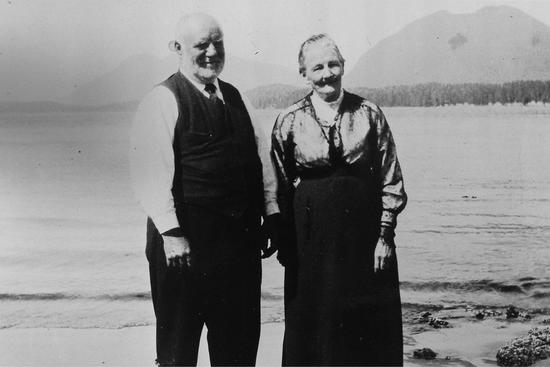

Like all other settlers, John Grice set out to make his mark in this new territory. He quickly learned to communicate in the Chinook trading jargon and began to act as an intermediary between the local hunters and the sealing schooner captains in their hiring negotiations. As a literate Englishman, later described by Dorothy Abraham in her book Lone Cone as “a very learned man, a great lover of Shakespeare and all the classics, also something of an astronomer,” Grice possessed a decided advantage when it came to acquiring local government jobs that provided stipends. By 1895 he had been appointed shipping master and Justice of the Peace for Clayoquot. Later years would find him filling other official positions, including customs officer, tide and rain gauge supervisor, and fisheries officer.

For most of his first two decades on the west coast, Grice lived as a single man. In 1912 his wife, Jane, joined him, setting sail from England aboard the Empress of Ireland with their daughter, Jennie, by then in her late twenties. The couple’s long separation still perplexes their descendants, some believing that John Grice may have fallen into disfavour for fathering a child or children out of wedlock in England. The birth certificate of his young son, Arthur, who accompanied Grice to Canada, names one Mary Nesbit as Arthur’s mother, not Jane Grice. Dorothy Abraham wrote glowingly of the Grices in their later years. “He was rather like a rosy apple to look at,” she declared, describing a punctilious early riser who drank gallons of cold water, and whose frail, sweet-natured little wife dressed in old-fashioned silk frocks and beribboned bonnets. They both lived out their days in Tofino; Grice died of cardiac failure in 1934 at the age of eighty-four. His wife, also eighty-four, died three days afterward of chronic bronchitis.

Looking at Grice’s earliest plan for the townsite that became Tofino, his own personal property stands out. He retained the very tip of the peninsula, now called Grice Point, for himself and built a house there. From 1901, the Chinese trader Sing Lee operated his store on the shoreline nearby, possibly on the same site briefly used as a trading post by Hugh McKay in the 1860s, and later by David Evans in the 1880s. Much to Walter Dawley’s chagrin, Sing Lee enjoyed a brisk trade in furs and attracted some of Dawley’s regular customers to buy provisions in his store, including Elizabeth Chesterman, who, when her husband could not take her by boat over to Clayoquot, found it easier to trade at the “China store.”

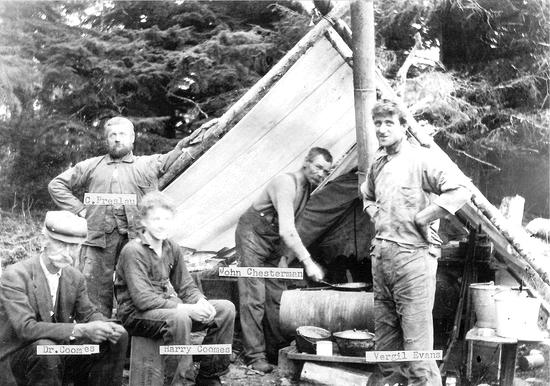

No one lobbied more energetically on behalf of the new settlement than John Chesterman. He felt sure the early settlers would succeed in creating a lasting community, with a dock, post office, school, stores, and many other amenities. Chesterman had been in the area since taking up his first seventy hectares of land in 1895, adding the adjacent sixty-seven hectares in 1900, which gave him ocean frontage encompassing all of what are now called North and South Chesterman Beaches. He cleared land and built a house on the sheltered inlet side of the property, and settled there with his young wife, Elizabeth, following their marriage in 1901. Their first child, John Filip Reginald, was born later that year. Chesterman kept his finger on the pulse of every potential development in the area, informing himself about local politics, remaining close to Harlan Brewster of the cannery and to A.W. Neill, the west coast Indian agent, later elected Member of Parliament for Comox–Alberni. When word came in 1901 that the Dominion Government Telegraph Service intended to extend the telegraph line from Alberni to Clayoquot, Chesterman pushed to have the terminus at “the settlement” on the peninsula rather than extending it underwater to the community on Stubbs Island. Although the telegraph, completed in 1902, officially terminated at “the settlement,” an underwater line did reach over to Stockham and Dawley’s establishment, possibly because they lobbied even more energetically than Chesterman and likely resorted to bribery to make this happen. At least initially, most of the telegraph business went through the telegraph operator at Stockham and Dawley’s.

Chesterman found lucrative employment for an eighteen-month period as foreman of the local telegraph crew during the installation of this line. He obtained many jobs over the years: building roads to Ucluelet and to Bamfield, on the telegraph line, at the cannery, and on the construction of Estevan lighthouse in 1908. Many of his letters to Walter Dawley survive, placing orders from his various workplaces for everything from “jap rice” to dynamite, all written in a meticulous script and often including wry jests.

In the spring of 1901, settler George Maltby landed the job of enumerator for the census in Clayoquot district. Over nearly three months, travelling mostly by rowboat, he listed the settlers in the Tofino area, on Stubbs Island, and at Opitsaht, Ahousaht, and Hesquiaht; he even included the staff of the recently established Christie Indian Residential School at Kakawis on Meares Island, and the Chinese workers at the cannery and the hotel. No Indigenous names appear; records of their population relied on the efforts of government agents and missionaries, and later on band lists assembled by Indian agents.

Most of the seventy-two men enumerated by Maltby in 1901 described themselves as farmers or miners, with a handful of carpenters and prospectors. Seventeen had wives living with them, and eleven of the wives had children. The Guinard (or Ginnard) family, living at the southwestern corner of Meares Island, then had five children; the Arnets three; the Wingens one. With the pace of settlement gradually increasing and the birth rate rising, a school was needed. To qualify as an “assisted” school, with the provincial government covering a teacher’s salary, at least seven children had to attend regularly. According to Catherine (Katie) Monks’s brief history of Tofino, in the booklet Cedar Bark and Sea, “Two French-Canadian families had pre-empted up the Inlet…between them they had over twenty children.” The 1901 census does not reflect these numbers, but Katie Monks could have been referring to the Guinard family and possibly the families of Paul and Nelson Fayette, who pre-empted land up the inlet in the mid-1890s but did not remain long in the area.

A newspaper clipping in a scrapbook created years ago by Daphne Gibson mentions a receipt dated April 23, 1899, made out to Auseth and Wingen for materials for the “Clayoquot Schoolhouse.” This shows that the schoolhouse had purchased some 8,000 board feet of lumber from these local sawmill owners, who forgave part of the $57.60 owing, donating $17.50 to the “Clayoquot School Fund.” Not much evidence survives of this early Clayoquot school, but its location is recognized in a commonly used place name: Schoolhouse Point, up Browning Passage, at the entrance to South Bay. Provincial school records indicate the school opened in 1898, with twelve children enrolled the first year; the teacher, Miss A. Doran, received fifty dollars per month. The following year, three different teachers worked at the school, a high turnover perhaps explained by the drop in salary to forty dollars per month. In 1900–1901, still with twelve children in attendance, the doctor at Clayoquot, Dr. P.W. Rolston, served as teacher. The school operated only forty-four days that year, and it likely closed the following year. Hints of moving this original schoolhouse to “Clayoquot” emerge in Walter Dawley’s correspondence, not indicating if that meant to Stubbs Island or to the emerging Tofino townsite, nor if the building was ever moved. In 1903, James Redford, an Alberni merchant active in provincial politics, wrote to Dawley saying, “The schoolhouse will remain where it is and the townsite also.”

Young Alma Arnet attended school at Schoolhouse Point only briefly before it closed, her father Jacob taking her there by rowboat or sailboat. When interviewed later in life, Alma remembered her family moving to Ucluelet for a year and a half, where she attended school with several other youngsters in the front room of their teacher’s home. Jacob found work with the Sutton sawmill in Ucluelet during this period, all the while continuing his seasonal work at the Clayoquot cannery and keeping an eye on his homestead and livestock at Mud Bay. Every summer, with Jacob working at the cannery, the Arnet family moved onto a floathouse anchored near the cannery, much to the delight of the children.

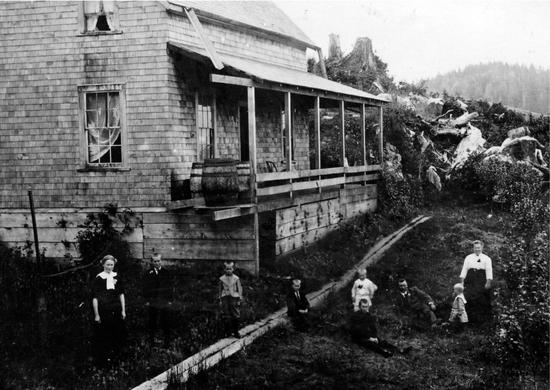

In 1906 the Arnets returned from Ucluelet to find a small school operating in Tofino. Accounts of this school vary, but it likely started in a private home, shortly afterward replaced by a one-room schoolhouse built by volunteers on land cleared by George Maltby at the corner of what is now Third Street and Campbell. To be near the school, Jacob Arnet built a home on the waterfront in Tofino, and the family moved from their homestead into “town.” Several other families who initially lived farther away from the townsite also moved into town, including John Chesterman and Tom Wingen. In addition to the Arnet family, Chesterman and his wife, Elizabeth, contributed to the required head count for the new school, as did Francis Garrard and his wife, Annie, whose children bravely came to school in Tofino by rowboat, a perilous journey from their isolated home on the new Lennard Island light, constructed in 1904. Formerly employed in the construction of the telegraph line between Alberni and Clayoquot, Garrard had come to Lennard Island to assist in building the new light station. He stayed on as lightkeeper until 1908, when he moved his family to Vargas Island and later into Tofino. He and Annie had eight children in all, several of whom attended school in Tofino.

The first Tofino school and its teacher received an approving nod from the British Colonist in June 1906: “The school started on Clayoquot townsite, so ably presided over by Miss May Clark of Victoria, has been very successful so far, the daily attendance averaging 12 scholars.” In fact, some twenty-eight students appear on the official enrolment for the school that first year—absenteeism clearly ran high—but nonetheless the school at Tofino, called Clayoquot School until 1924, never looked back. In 1909, W.A. (Bert) Drader came to teach there; thanks to him, many early photographs of the area now survive.

The coastal steamers sometimes called at Tofino now, on their twice-monthly trips up the coast, even though the place did not as yet have a dock, and all supplies had to be offloaded onto scows and small boats. With ambitious new developments underway, like the Mosquito Harbour sawmill, newcomers continued to arrive at the townsite, a few at a time, some just passing through, some coming to stay. Among the long-term players was the quick-witted trader James Sloman.

Sensing a golden opportunity at the emerging townsite, Sloman abandoned his storekeeping job with Walter Dawley to become his direct competitor across the water at Tofino. Dawley was not amused. He had already been double-crossed by Thomas Stockham, who walked out on their partnership in 1904 in a bitterly acrimonious dispute. Stockham then purchased two sealing schooners and carried on trading seal skins and furs in defiance of Dawley, using Sing Lee, the Chinese storekeeper in Tofino, as a middleman. Stockham even provisioned his boats through Sing Lee, the very man he and Dawley had tried so hard to put out of business. With Sing Lee’s sudden death in 1906, Stockham and James Sloman acted together to seize the moment. Sloman formed a partnership with Stockham’s brother-in-law John McKenna, and together they purchased the “China store,” almost certainly with help from Stockham, knowing full well that Dawley had also been trying to acquire this store.

A wily operator, James Sloman learned all the tricks of the trade from Dawley, having worked for him at the Nootka store for five years, and briefly at Clayoquot. He well knew the importance of acquiring additional services to create a thriving enterprise, and within three years a post office found a welcoming corner in Sloman’s store, bringing with it increasing traffic and trade. With the arrival of its own post office, the name “Tofino” became formally accepted in the community: the names “Lone Cone” (for the mountain) and “Riley” (for Reece Riley, an early settler) had been considered, but “Tofino” triumphed, taking its name from Tofino Inlet. The inlet had been named in 1792 by Spanish captains Galiano and Valdés, honouring Spain’s chief hydrographer, the renowned astronomer and mathematician Vicente Tofiño de San Miguel.

E.B. (Burdett) Garrard, Francis Garrard’s brother, became the first Tofino postmaster in 1909, by then having already served two years as the Tofino telegraph operator. Burdett built his home around the telegraph office and later expanded operations when he moved the post office to the same location. This communication hub remained in the Garrard family for years to come. In 1911, when Burdett and his family moved to Alberni, Francis Garrard became Tofino’s next postmaster and telegraph agent He held both positions, with the assistance of his wife and daughters, until 1924.

While it became increasingly evident that this new Tofino townsite had come to stay, the strong arm of the law remained firmly based at the established settlement of Clayoquot on Stubbs Island. Following the departure of Constable Spain in 1902, Constable Daniel McDougall took over at Clayoquot, remaining there for over five years before Ewen MacLeod took over from him. MacLeod had first seen the area early in 1905 when working as a seaman on the sealing schooner Charlotta G. Cox. According to his niece Mary Hardy (née MacLeod), “When he viewed Lone Cone and the mountains surrounding the harbour, it reminded him so much of the island he came from (Raasay, on the northwest coast of Scotland) he determined to return.” In 1906, Ewen joined his older brother Murdo, who had arrived on the coast the previous year and was working on the road at Bamfield. Ewen heard of the opening at Clayoquot for a police constable and applied. Both brothers came to Tofino, Murdo finding work at the Mosquito Harbour sawmill—for which he received $1.10 per day—and in various construction jobs. Murdo and Ewen were the first of several MacLeods to come to the area—another brother, Alex, followed in 1911, accompanied by his cousin John (Jack) MacLeod and an unrelated John MacLeod, whose sister Julia later married Murdo MacLeod.

Ewen MacLeod felt entirely at home in the damp, grey, island-strewn landscape, and far better suited to this life than to his earlier police work in Glasgow. He enjoyed the hunting and fishing, and like Constable Spain before him he travelled far and wide around Clayoquot Sound in his rowboat, ranging farther afield, to Nootka and to Kyuquot, by steamer when necessary. Having been brought up in a crofter’s cottage, both Ewen and Murdo MacLeod well understood hardship and poverty, and they felt an affinity for the growing plight of the Indigenous people as their access to traditional lands and resources diminished.

When he began working at Clayoquot in 1907, Constable MacLeod’s pay stood at seventy-five dollars per month, five dollars of which went toward renting a cottage from Walter Dawley. Attached to this cottage stood the rudimentary jail, built in 1906, complete with ringbolts embedded in the walls. Over the years, this jail occasionally housed prisoners for short periods—sometimes those awaiting transport to face charges in Victoria, sometimes seal hunters who jumped ship, breaking their agreements with the captains. In March 1907, when Father Charles Moser’s motor launch Ave Maria suffered mechanical problems, he turned to the Clayoquot jail for assistance from the “2 Nootka Indians in jail [who] had deserted their sealing schooner. At my pleading and promise they would return to jail these 2 Indians towed my launch to Opitsat with their canoe and after a good meal returned to jail.” In later years, rebellious runaways from residential school were sometimes tracked down by police and truant officers and held in this jail before being returned to school. More often than not, though, the jail simply served as a drunk tank. With many sealing schooners still visiting Clayoquot Sound to pick up hunters and replenish supplies, the bar at the hotel on Stubbs Island, the only one on the west coast north of Victoria, did a booming business. Veteran sealing captains like Alex MacLean and George Heater would stop by, needing to boost their morale as their livelihoods slowly vanished, and the bar regularly welcomed workers from Mosquito Harbour, along with the usual traffic of prospectors. This kept Constable MacLeod busy, for often the “uncivilizin’ influence of Clayoquot liquor” led to barroom brawls, forcing him to intervene.

Prior to his marriage in 1911, Ewen MacLeod often took his meals at the Clayoquot Hotel, paying twenty-five cents for breakfast, fifty cents for dinner. His precise account book shows that for $2.50 per month he had a standing order for milk from the one cow at Clayoquot, and that he bought salt cod from the fish saltery on Stubbs Island for twenty-five cents per fish. For seventy cents he could purchase over a kilogram of smoked salmon from Indigenous families, and tins of salmon from the Clayoquot cannery cost twenty-five cents each. He made no mention of buying a drink at the Clayoquot Hotel, but clearly various MacLeods enjoyed good times there. In later years, Ewen wrote to Walter Dawley, saying: “I trust you will keep the MacLeod boys in order…don’t let them drink too much boose.”

In 1910, on a trip to the sawmill at Mosquito Harbour, Ewen MacLeod met Mabel Reeves of Seattle, holidaying with the summer caretakers. Evidence of his attraction surfaces in his account book: one box of chocolates, $1.00. They married the following year, and Mabel gamely settled into life as the local policeman’s wife. One of the perks, when the first baby arrived, was the extra space in the jail next to the house: an excellent place to dry diapers on a rainy day. The MacLeods left Clayoquot in 1914, first moving to Hope, and later to Lytton. They had purchased their cottage at Clayoquot from Dawley, and it remained in the MacLeod family until the 1960s.

The year 1908 saw significant changes at Tofino. The much-desired government dock went in that year, at the location occupied today by the First Street dock. This large structure, extending sixty metres offshore, finally established Tofino as a regular stop for the coastal steamers. Prior to this, the coastal steamer Tees would not stop at Tofino unless at least three tons of freight had to be unloaded, which meant the Tees holding her position offshore, arduously shuffling freight from her cargo deck onto a scow, and landing goods on the beach. With a decent dock, Tofino could now rely on mail and supplies arriving three or four times each month. The 1909 schedule for the British Columbia Coast Steamship Service of the CPR still insisted on calling the community “Clayoquot townsite,” but by 1910 the name “Tofino” appeared as a fixed stop on the schedule.

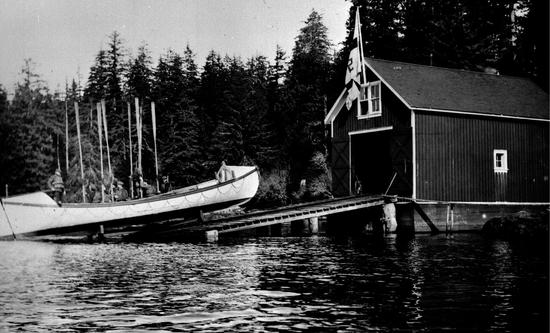

Another proud new institution began in 1908 with the establishment of the Clayoquot lifeboat, an essential service that over subsequent years employed scores of local men. As coxswain, John Chesterman had charge of maintaining the vessel and managing a crew. Bernt Auseth constructed the boathouse for the new lifeboat on a waterfront lot in Tofino that had been purchased for fifty dollars by the Department of Marine and Fisheries. Powered by oar and sail, the lifeboat required ten men to row any distance, leaving little space on board for shipwrecked victims; at most three or four passengers could be safely taken aboard at one time. Originally manned by volunteers, before long the lifeboat crews received hourly pay when on duty, and the coxswain enjoyed an annual salary. Apart from being on call for emergencies and regular drills, the crew also cleared land, built fences, and maintained the property around the boathouse. One crew member kept watch at night, and the single men on duty slept at the boathouse in the uncomfortable loft. Married men, if they lived nearby, slept at home. In the early days, the lifeboat sometimes even served as a means of transport for taking new settlers to their homes. By 1913, because the original “surf boat” faced increasing criticism for its evident limitations, the inspector from Victoria recommended that the boat be replaced by a motorized vessel.

As time passed, the lifeboat station took on an increasing roster of duties: provisioning and delivering mail to Lennard Island light; monitoring the official gauges for tide and rainfall; maintaining the increasing number of whistle buoys, markers, and lights in the harbour. The lifeboat crew could be called on to assist at any local emergency, including fires and medical calls, ranging all over Clayoquot Sound and down the coast along Long Beach to Ucluelet. The lifeboat also served to transport coffins for burial in the town cemetery on Morpheus Island. It became a fixed point of reference in town; a reliable source of employment for many men, and a source of considerable local pride.

The year 1908 also marked the arrival on the west coast of a self-effacing young man, Frederick Gerald Tibbs, destined to become one of Tofino’s best-known characters. At first glance not a prepossessing character, Tibbs appeared stocky and rather shy, painfully self-conscious about a facial disfigurement dating back to a childhood injury in England and made worse by various surgeries. Benignly good-natured and cheerfully eccentric, Tibbs first settled on land he pre-empted at Long Bay (Long Beach), a considerable distance from Tofino and from other settlers, the area now occupied by Green Point Campground. Strangely keen on physical exercise, Tibbs caused locals to shake their heads when they heard he took a plunge in the breakers at Long Bay every morning, followed by an energetic run round and round a huge tree stump on the beach. Tibbs wrote voluble, friendly letters to Walter Dawley, including fussy and precise shopping lists. He ordered such items as “limewater glycerine” for his hair, lemons, mousetraps, nails, thimbles, a blue sweater, and on one occasion a can of bright pink paint, enclosing a sample of rose-covered wallpaper providing the hue to be matched. After passing on good wishes to everyone in the “liquid dominion of Clayoquot,” as Tibbs called Dawley’s establishment, he signed his name in a flourish of calligraphic curlicues. While living at Long Bay, Tibbs gave his return address as “Tidal Wave Ranch.” He did no ranching there, but filled his days clearing land and establishing himself in a rough little cabin “built out of driftwood and gas cans and made quite ornamental,” according to Mike Hamilton’s memoirs, and featuring—if the paint did arrive as ordered—a rosy pink interior.

Early in 1910, Tibbs left Tidal Wave Ranch and took a job on remote Triangle Island off the northern tip of Vancouver Island, which he described as “this mountain top, surrounded by ocean.” Tibbs assisted there with the construction of a new lighthouse, sending to Dawley for tennis shoes and a “good deep-toned mouth harp,” to be shipped up on the supply vessel Leebro. He saved enough money for a trip to England, but by November 1911 he was back at his “ranch,” in his spare time busying himself as president of the Clayoquot Conservative Association. The following year Tibbs took a job at the Kennedy Lake salmon hatchery and found himself increasingly drawn to Tofino. A small 1.2-hectare island in the harbour caught his fancy, so he sold his property at Long Bay and bought the island, which he christened Dream Isle, painting the name in huge white letters on the rocks. Here, Tibbs began to pursue his dreams, with the village of Tofino watching in complete astonishment.

In the first of many unexpected moves, Tibbs set about clear-cutting the entire island, blasting out stumps whenever he could. He had a fondness for using large amounts of dynamite; loud explosions from Dream Isle became commonplace. Ignoring Jacob Arnet’s kindly suggestion that he leave at least some trees for wind protection, Tibbs left only one tree in the centre of the island, an enormous spruce that he topped at thirty metres. Over time, he removed every limb, leaving a tall standing spar. Up this he built a sturdy ladder, almost a small scaffolding, mounting all the way, step by step, to the top, where he constructed a narrow platform. According to local legend, he would climb to the platform every morning with his cornet and serenade Tofino with lively tunes, in particular “Come to the Cookhouse Door, Boys.” Having first lived in a tent on the island, Tibbs gradually built his dream home, a wooden castle, three storeys high, complete with a crenellated tower and battlements. Painted red, white, and blue, held to the rocks with steel guy-wires, the castle eventually housed a piano and a phonograph, with a garden alongside featuring trellised roses, a loveseat, and a sunken well. Inside, the walls were “beautifully ornamented by artistic designs in plaster work,” according to George Nicholson, who managed Dawley’s hotel at Clayoquot during the 1920s. Tibbs lived on the ground floor; the upper levels remained unfinished and accessible only by ladder. In the years leading up to World War I, Tibbs had just begun all this work; he continued doggedly on, year after year, with each new development establishing him ever more firmly as one of Tofino’s leading eccentrics.

Although few could compete with Tibbs’s highly visible idiosyncrasies, from the earliest days of settlement the west coast consistently attracted its fair share of oddballs: independent, stubborn individuals determined to go their own way, brooking no interference. Solitary, a little—sometimes very—peculiar, these men (and they were always single men) tended to disappear up the inlets or into the bush, finding remote places to live undisturbed, coming to town only when it suited them. Dorothy Abraham described how one of them, “tucked away in the most remote part of Kennedy Lake…lived year in and year out in the solitary wilderness,” and how another, “the dirtiest specimen of humanity you could ever imagine,” built a house on a cliff on a distant outside beach, lived on “coon meat and candied peel from kelp,” and astounded everyone near the piano at the Clayoquot Hotel on one occasion with his exquisite rendition of Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata.

In his memoirs, Mike Hamilton also noted the presence all over Clayoquot Sound of “weird individuals, bearded and long-haired who somehow lived hidden away in some remote location,” particularly recalling the American known as Fitz. Formerly a cowboy in Montana, Edward Fitzpatrick arrived on Flores Island in 1915, having pre-empted land sight unseen on the northwest coast of the island. He arrived aboard the Tees with a bull, two cows, two horses, some chickens—and even a plough, according to Hamilton. With no dock at Ahousaht, the large animals had to swim for shore, while the missionary John Ross helped Fitz land the rest of his gear and the chickens by canoe. Fitz insisted he would farm his remote tract of land, even though, in John Ross’s words, it consisted only of “muskeg and moss...[with] hard pan not far below.” Laboriously, Fitz transported everything to his property by canoe, driving the larger animals along the shore and through the forest. He led an entirely solitary life in the cabin he built, emerging every month or so to purchase supplies, “a gaunt, unshaven figure, barefooted and clad only in overalls.” In October 1915, Fitz came to the Ahousaht store to purchase flour and coal oil, and headed out the next day in his skiff, planning to row the long distance home. Several people saw him off, including Mike Hamilton. Over two weeks later, a group of local boys, combing the shoreline for debris from the Chilean barque Carelmapu, recently wrecked off Schooner Cove, discovered Fitz’s homestead deserted, the chickens dead, and no sign of life. Fitz had never made it home. Some Ahousahts finally spotted him marooned on an exposed rocky islet in a terrible state of emaciation and distress. He had survived the swamping of his boat and struggled to shore, salvaging the sack of flour, a can of kerosene, and a few other items, including five precious matches, stashed in his hair to keep dry. He sheltered in the roots of a tree, lit a small fire, and somehow survived for nineteen days. Father Charles Moser received word of Fitz’s rescue from Pascal, one of the men who saved him. Fitz had written a note to the priest, explaining what happened: “Mr Pascal he got me of Iona Isl in sea where I was wrecked and I froze and starved 19 days. Will pay him well...God will be praised and glorified.” Mike Hamilton wrote of Fitz with awe, in part because of his spectacular body odour and the caked black mud that had to be scraped off him by John Ross in an enforced bath at the Ahousaht mission. Fitz returned to the United States in 1920.

A German man named Edmund Proestler also attracted considerable attention from time to time on his property at Long Beach. Strikingly bowlegged and very shy, he generally avoided people, working hard on his property where he could be, as Mike Hamilton recalled, “a one-man nudist colony. He worked so much with nothing on that he was almost as brown as an Indian.” Occasionally, surprised visitors would come upon Proestler working naked, and he would flee into the bushes. He rarely came into Tofino, especially after World War I began. He so feared being arrested and interned he would only visit the village after dark to buy food.

Another storied local character, Bill Spittal, hailed from Glenshiel, Scotland. For many years he lived on the north side of Tofino Inlet in a leaky one-room shack, its walls streaked with tobacco juice, his sole companion a disreputable old dog named Joe Beef. Everyone had tales to tell of Bill Spittal, and he spun many a yarn himself about his prospecting experiences in the interior of British Columbia—how his nose had nearly frozen off, and the number of toes he had lost to frostbite when he had been given up for lost by his companions. “You know, he never washed his teacup,” Ian MacLeod claimed. “It was just as if it had been varnished inside.” Ian and his six siblings grew up in Tofino, where their father, Alex, was in charge of the lifeboat for many years. Bill Spittal and his dog made a lasting impression on local youngsters, perhaps because big, shaggy Joe Beef had such a fearsome reputation. “He was vicious,” declared Ian. “The dog was deaf and dumb and he couldn’t bark or nothing but he went around showing his teeth all the time.” Bill and Joe Beef were inseparable, even sharing the same, unvarying diet of clams and ducks and fish. “You’d hear [Bill] passing down to Clayoquot to get drunk,” Winnie Dixson recalled. The daughter of Tofino’s first resident doctor, Winnie arrived as a young woman in 1912. “I’ve seen him singing for dear life and rowing. The tide was so strong he was going backwards when he thought he was going forwards.” Brisk, matter-of-fact Winnie declared in an interview with Bob Bossin in 1981 that she never had much interest in men, nor time for them; she had milking to do, and people she checked on and people who needed to be fed. Nonetheless, she had a soft spot for Bill Spittal. They became unlikely partners in several of his mining interests, and when he died he left everything he had to Winnie. After his death, another reclusive Scot, Bill MacKay, lived in Spittal’s cabin.

The BC Directory for 1910 contains an entry for Clayoquot that includes the Tofino townsite, giving the population of the overall area as “300 whites and 250 Indians.” The directory provides names and employment of the male settlers, most of them described as carpenters or farmers, some as prospectors and miners, only two or three as fishermen. The directory lists several local amenities, the Methodist hospital on Stockham Island, the lifeboat station, and telegraph and post office among them. The newly constructed community hall, built by volunteer effort, and measuring 19 by 12.5 metres, receives no mention, but no fewer than four local stores can be counted: one at Clayoquot cannery, Dawley’s store on Stubbs Island, Sloman’s store, and that of William Stone and his son Stuart in Tofino.

A few years earlier the Stones had set up a little store on the island still bearing their name in Tofino Harbour—likely just a small operation in their own home. They had lived on the island since 1904, and the highly capable Christina Stone did her best to create a productive garden there, even bringing over a number of cows and setting up a small dairy. Later they moved into Tofino from the island and briefly ran their small store there, assisted by Wallace Rhodes. For many years Stone had been the Methodist missionary at Clo-oose, and his storekeeping efforts so close to Clayoquot annoyed Walter Dawley. Just as he did with Sing Lee and James Sloman, Dawley tried to prejudice his suppliers against Stone, even though Stone posed no threat. Writing to Dawley in May 1908, he apologetically stated “that our little venture in the store business was not against you but simply a means to a living.”

Actively involved in local politics, Stone further infuriated Dawley by becoming leader of the newly formed Liberal Association, in response to the election of the Conservative Richard McBride as provincial premier in 1903. Following this election, the first in British Columbia involving party politics, Conservative and Liberal factions squared off locally, Dawley staunchly behind the Conservatives, Chesterman favouring the Liberals, in company with Stone. While Stone and his family lived in Tofino, his sons Chester and Stuart took over the machine shop started by Jens Jensen. After moving to Alberni in 1915, the family started a commercial transportation business that eventually boasted two well-known vessels, Tofino and Roche Point, frequently seen on the coast for years to come, delivering cargo and passengers.

Also in the 1910 directory listing for Clayoquot, an entry appears describing Dr. Melbourne Raynor, the Methodist doctor and missionary, as president of the Clayoquot Development League. This ambitious little organization, to which many prominent settlers belonged, emerged from the larger Vancouver Island Development League. Formed in 1909, the parent league brought together delegates “from...Quatsino; from Nootka, where marble quarries promise wealth...; from Clayoquot, from St. Josef and Holberg, from Banfield.” They gathered to discuss the needs of their communities, radiating boundless optimism about the future and a shared passion to acquire roads. All league members, in every location, campaigned vigorously for roads. At meetings of the Vancouver Island League, roads to Quatsino, to Nootka Sound, to Tofino and Ucluelet, to Port Renfrew all came under discussion. Mountain ranges, budgets, and all other obstacles seemed not to matter. “Modern engineering laughs at the obstacles presented by mountain heights,” declared a 1910 report on the development league’s work. Such minor details must be overcome, for “the pressure of an immense Dominion, rapidly being peopled with incoming settlers from every part of the world, is behind the west coast of British Columbia, and before it lies the unlimited and only partially explored markets of the far East.”

Writing of the development league in October 1910, the Colonist noted the recommendations made by Mr. J.J. Shallcross and other delegates who met with the premier and cabinet. “He recommended that the government be prepared to plant orchards to replace the Douglas Fir once the forest was logged.” The delegates also suggested “reducing the pre-emption acreage—say from 160 acres to 80 acres [65 hectares to 32.5 hectares]—as a means to encouraging closer settlement…to remove or minimize the isolation so keenly felt by the majority of pioneer settlers.” Harlan Brewster attended this meeting, announcing that “Alberni would be a railway terminal point in the very near future.” Here he proved correct: the Esquimalt and Nanaimo Railway did indeed come to Alberni in 1911. Less accurately, Brewster also said that “considerable progress had been made last summer on the Alberni-Clayoquot road,” a statement more hopeful than true. Perhaps because of this type of overstatement, the Colonist noted MLA John Jardine’s dry comment: “With respect to the settlers who were finding their way to Vancouver Island, he regretted to learn that they not infrequently found things not as they had been led to believe...He thought the Vancouver Island Development League might with advantage be more careful in its advertising campaign.”

In the years leading up to World War I, several development schemes on the west coast of Vancouver Island proposed wildly ambitious plans for settlement. Planners dreamed of remote Quatsino becoming a major railway terminus, a gateway to trans-Pacific trade. Land developers from Chicago created the short-lived Hesquiaht Land Company, noted in Father Charles Moser’s diary when some unknown Americans came to investigate their holdings. Walter Dawley fielded letters from many hopeful speculators, including a Mr. A.R. Love in Liverpool, England, who claimed he could invest untold millions in land, any land. At Clo-oose, the most difficult boat landing on the coast, the West Coast Development Company put forward the wildest of all schemes, promising unwary investors the next Atlantic City, a major seaside resort complete with an amusement pier, tennis courts, and golf links. Dozens of people bought land sight unseen on the exposed coast at Clo-oose, expecting a bustling settlement, only to be greeted with nothing whatever on their arrival.

Nothing so grandiose occurred near Tofino, but the same sense of immense possibility fired the imagination of some settlers, along with a tendency to minimize practical problems. By 1912, with Francis Garrard as president, the Clayoquot Development League published a pamphlet explaining that although a good deal of land in the area was already taken up, lots remained available for pre-emption or purchase, costing from five to ten dollars per acre. While extolling the mild climate and the fertile soil, and providing detailed prices for agricultural produce—“butter brings 35 cents to 45 cents per pound, chickens, dressed, from 75 cents to $1.25”—the pamphlet conveniently failed to mention problems of transport or access to outside markets.

The most ambitious land development scheme near Tofino occurred on Vargas Island. Following the tragic death of their infant son, Edward, who died on Lennard Island in 1908 after accidentally eating a piece of lye, Francis and Annie Garrard decided to leave the light station. Pierre Hovelaque invited Garrard to join him in “taking up land and…holding it for sale making some profitable transactions,” as Garrard wrote in his memoirs. On Vargas Island they obtained as much land as they could by pre-emption, lease, and purchase, “making in all 1280 acres [518 hectares] we would have control of, for our purpose.” The two men started energetically, as Garrard’s memoirs attest, each building a cabin and then clearing a “fair sized track” of land and seeding it in grass for future ranching. They even attracted the attention of “an American stock owner who looked over the land with a view of running stock on it,” but the idea fell through. Having expanded their cabin, planted some fruit trees, and started a small garden, the Garrards split their time between Vargas and a home they had in Tofino. By carrying out various “improvements” to the land on Vargas, including land surveys and some clearing, fencing, and building, as well as bringing goats and a cow or two to the island, Garrard felt sure its value had increased. “We could feel we were rapidly becoming wealthy, on paper…we hoped by the disposal of the land as planned to make ourselves into a solvent concern.”

Pierre Hovelaque made a trip to England shortly after he and Garrard acquired land on Vargas, and while there he likely advertised the land as being available for settlement, or he may simply have circulated the information among friends and acquaintances. Word spread, and Vargas Island succeeded in drawing a good number of British settlers, most without the faintest idea of what faced them. Young, single men arrived first, including Arthur and Ted Abraham, Donald Forsythe, Frederick Sydney Price, Freeman and Frank Hopkins, and their distant cousin Harold Monks. Several of them regularly ordered supplies from Dawley’s store at Clayoquot, including Harry Hilton, who wrote for advice in March 1912: “Two or three weeks ago a party of four of us…secured a pre-emption each. We intend going into Residence in the near future & would like to know if it would be advisable to take up a stump puller.” Expecting to be able to farm, they grappled with acidic and boggy soil, isolation, and major logistical challenges on an island well removed even from the marginal settlements nearby. Before long most of the young men sought additional employment, and after building their cabins on Vargas, several of them, including Harold Monks, found work at Clayoquot cannery.

Some of the men attracted to Vargas later brought their wives and extended families to the island. A small group settled at the north end, naming their cluster of homesteads Port Gillam, after the well-known steamer captain Edward Gillam; some surviving letters also refer to it as Port Vargas. They optimistically constructed a wharf there in the winter of 1914; it did not last one season before being destroyed in winter storms. The coastal steamer called regularly at Port Gillam for several years, even after the wharf disappeared. Away from this community, other settlers could be found in scattered homesteads around the island, several in the southeastern section, and one couple, the Clelands, in Open Bay (Ahous Bay) at the western side of the island. Famously, Cleland and his wife took horse and buggy rides, just for the fun of it, along the vast stretch of sand in the bay. Just how the horse and buggy came to be at this remote location beggars the imagination; no road but a rough corduroy trail stretched across the island, often floating in mud across boggy sections. Building and maintaining this trail was an arduous and thankless undertaking requiring the assistance of oxen. Traces of the trail can still be seen on the island.

Helen Malon stands out as one of the more unlikely settlers on the island. In July 1912, freshly arrived from England and en route to Vargas, she wrote in her diary: “Arrived Clayoquot about 3PM. Had to stay there the night as our beds had only arrived the same boat as us. Very primitive little place, hotel, one store, P. Office, Police station…there are other small settlements and Indian villages on the mainland and islands round. Hotel queer and primitive, but clean. John Chinaman cook, housemaid etc. We were introduced to various [settlers] all more or less queer, mostly more.”

Helen came to this “queer” place at the urging of her two sons from her first marriage, Ted and Arthur Abraham, and her brother Arthur George Anderson. All three had taken up land on Vargas Island in 1911, a combined total of 203 hectares. Perhaps dazzled by this amount of land, Helen, widowed by her second husband, emigrated with her grown daughters, Violet and Eileen Abraham, and her two younger children, Pierre and Yvonne Malon. They planned to build a comfortable house, establish a farm, and start anew.

Vargas Island proved a far cry from the comfortable middle-class life the family had led on the Isle of Wight, in their large home with servants. “It was quite a shock to our feelings to find no house, only a shack,” Helen wrote after her first nerve-wracking trip over to Vargas, with the family’s goods loaded into a canoe and towed to the south-facing beach. “We have gone to a primitive life and no mistake, but I think we shall like it all right,” she bravely asserted a month later. With significant gaps, her diary covers the years from 1912 until 1919, providing a terse commentary on the difficulties faced by a settler who found herself isolated, facing hard physical work, and in many ways entirely ill-suited to the life. She longed to be able to attend church regularly; she brought both a piano and, on one occasion, a piano tuner over to the island; she loved doing fancy needlework; and she suffered persistent ill health.

According to Francis Garrard, Helen Malon purchased less than a hectare of the land he and Hovelaque had owned, in the bay just east of Garrard’s own Vargas home, looking over toward Stubbs Island. Garrard had quickly lost interest in the Vargas Island land scheme; by the time the Malons arrived, he and his family had moved into Tofino, and his partnership with Hovelaque had dissolved. Hovelaque remained on Vargas, and in 1920 he married Violet Abraham. They stayed on the island longer than any others and were still there in 1926, leading, as Garrard stated, “a very secluded life.”

Helen Malon hired Hovelaque, along with other Vargas settlers, to build her new house in the bay she called “Suffolk Bay,” from where she could see the boat traffic heading in and out of Tofino Harbour. Her sons Ted and Arthur settled into cabins on the more remote western side of the island, facing Wickaninnish Island. Years later, after World War I ended, her daughter-in-law Dorothy Abraham, married to Ted, decisively concurred with Helen’s choice about where to settle on Vargas. “It seemed so difficult to believe that literally there were no roads of any sort, only blazed and partly cut out trails leading through the dense bush, through swamps, sometimes on floating corduroy on which we slipped and slithered, often more or less under water or mud. No fields! No grass! No people! No anything!” After the briefest experience of Ted’s remote cabin, Dorothy declared, “My heart sank…then and there I told him I could not endure such loneliness…we decided right away to build on the other side of the island, next door to my in-laws.”

Despite its brevity, Helen Malon’s diary provides clear insights into the life of a European woman in Clayoquot Sound. No comparable document has survived. In particular, her diary shows the relentless amount of work required to establish and maintain a garden, and the urgent need to produce all the vegetables and fruit possible. Helen coaxed a profusion of black and red currants, strawberries, gooseberries, asparagus, peas, marrows, celery, cabbages, potatoes, beans, and other vegetables from the soil, not to mention the roses and geraniums she so loved. She fertilized with starfish, herring roe, sacks of herring, chicken manure, seaweed, and she never ceased trenching, digging, expanding. Once into her new house, she planted fruit trees of all descriptions. Jam-making filled a great deal of her time at harvest season; even in the dark of winter she did not stop, making nine kilograms of apricot jam one November from dried apricots, similarly peach jam from dried fruit, and always vast quantities of marmalade—13.6 kilograms in one go early in 1916—using marmalade oranges from the store at Clayoquot.

Unlike many settlers, Helen Malon evidently had at least some disposable income. She hired other settlers to build her home; she frequently employed Indigenous help—named in her diary as Skookum Charlie, Big William, and Mr. Tom—to help clear land and cut wood; a woman named Jessie came to do the laundry. The new house had plenty of space and some elegant touches, including decorative panels of stained glass and carved corbels. Insofar as she could, Helen maintained the habits of a gentlewoman, passing days writing letters, devoting considerable time to making lace, confessing to being “too slack to do much but read all day.” Her diary describes many occasions when she spent entire days in bed feeling unwell. Subject to fits of malaise, which she described vaguely as “felt rather seedy,” “tired and stupid,” “felt rather a wreck,” Helen went through many bad spells and took to her bed.

Some diary entries revel in the natural beauties surrounding her. She took time to marvel at the “lovely great waves dashing in to the bay,” “the sea magnificent, lovely bright dark green.” She wrote of feeling “breezy and free” walking over the sands, and delighted in moonlit nights and the “phosphorous” in the sea. Settlers rarely indulged in such comments in their practical, matter-of-fact diaries or letters. In nearly thirty years of diary writing, Father Charles Moser expressed almost no interest or pleasure in the surrounding scenery; nor did Francis Garrard in his memoirs. Yet in the few years she kept this diary, Helen Malon frequently did so.

Repeated themes in the diary show unceasing anxiety about boats and weather, near-desperate anticipation of mail, and continual worries about the children’s health and about bad teeth, which plagued everyone. Oddly, Helen Malon received dental care on one occasion from “Young Brewster,” who came to Vargas and removed two of her teeth—apparently Raymond Brewster, the eldest son of cannery owner Harlan Brewster. Another day she went up the inlet to the cannery with a family member “to have teeth seen to.” Her diary gives vivid snapshots of unusual events: the entire lifeboat crew arriving on Vargas unannounced and having to be fed; the astonishment of an Indigenous woman seeing Violet Abraham wearing only a “bathing dress” as she worked in the chicken coop; the eager anticipation of a visit from the Chestermans, with a special cake baked, and sharp disappointment when they did not come. Detail after detail unfolds: bartering for fish with local people, purchasing woven baskets, awaiting news of a delayed steamer, and whenever possible getting off the island and going over to Tofino, in whatever vessel proved seaworthy—and many did not—to attend church.

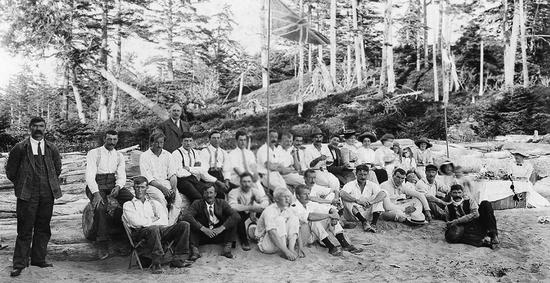

Churchgoing initially meant going to services in the Tofino community hall; occasionally services even took place on the beach at Vargas, if a clergyman would come over. In July 1913, however, a team of volunteers, including Francis Garrard, Jacob Arnet, and John Chesterman, started to build a church in Tofino. On October 13, the first church service triumphantly took place in the new St. Columba Anglican Church. The idea for a church first arose in 1910, “during a picnic…on Vargas Island, at which were most of the inhabitants of Tofino and Stubbs Island,” according to Garrard’s memoirs. They held a meeting and decided to approach the Anglican diocese about establishing a parish. Fundraising soon began, staunchly supported by many locals and assisted by an endowment from the British philanthropist Baroness Angela Burdett-Coutts. The church also benefited from a bequest to the diocese by the family of Francis Beresford Wright in England, who wanted to contribute to build a church in a place of beautiful natural scenery. Over a century later, this church still stands in the town centre, lovingly maintained by a dedicated handful of people.

No substantial information appears in Helen Malon’s diary about how the Vargas settlers interacted with Indigenous people living nearby, but evidently conflicts and tensions did arise. The Vargas people had placed themselves in traditional territory of the Kelsemaht people, now amalgamated with the Ahousaht, and the presence and attitudes of the newcomers caused much consternation. In May 1914, speaking of the Vargas settlers in his testimony to the McKenna–McBride Royal Commission on Indian Affairs, Chief Billy of the Ahousaht stated, “We are having trouble all the time.” Chief Charlie Johnny of the Kelsemaht also testified to the commission about Vargas: “We had houses there, and we used to live there all the time—It was not Reserve but we used to live there all the time…I wrote to Mr. Neil about it, he was then the Indian Agent. I got an answer in which he said that white people had come on that place, and we would have to take our houses down, and said if we didn’t Abraham would burn all the houses down.”

Accustomed to coming and going freely on Vargas Island, the Kelsemaht and Ahousaht people simply could not comprehend white people settling there. Several houses built by Indigenous people, most occupied seasonally, stood on lands taken up by settlers. According to George Sye’s testimony to the McKenna–McBride Commission, one of the Abraham brothers felled a tree right through his house. “I said to him you had better not take down that tree until I have moved my house. But that same day he felled the tree, smashing my house all to pieces.” At least two other settlers, Frank Perrotta and one of the Hopkins brothers, took possession of Indigenous houses and lived in them for a while. “The House was there before Hopkins came along,” Chief Billy protested. “It was built a year before he came, and I want to know if it is right for a whiteman to come along and live in the place where the Indians have been living long years ago. Is it right—I would like to know—I don’t want whitemen to come along and take the places where the Indian houses are.”

To provide background to this dispute, Indian agent Gus Cox explained to the commission that one or both of the Abraham brothers had taken up land on an old Kelsemaht village site. “Mr. Abraham” had offered to provide 1.2 hectares of land elsewhere on the island in return for the village site, and an agreement had been drawn up to that effect. This arrangement quickly proved unworkable, because in the shuffle of lands the local people lost their excellent landing beach on the southeast corner of Vargas. Their objections led them to apply for extra reserve land on the land bordering this beach, at the old village site. The application proved successful, with the granting of a new eleven-hectare reserve there in 1916.

Before World War I, opportunity and optimism abounded for the settlers in and near Tofino. With a good dock, regular steamer service, a community hall, church, customs office, post office, school, and even a short-lived hotel/boarding house called the White Wing Hotel, the place seemed set to thrive. Lots in the Tofino townsite sold for about a hundred dollars, and eager campaigning for a road to Ucluelet continued. Energized by service organizations like the Women’s Auxiliary of the church, the Settlers’ Association, the Clayoquot Development League, and the Overseas Club, the town now had far more people than Clayoquot on Stubbs Island. Nonetheless, Garrard’s memoirs darkly hint at more than one political plot in the pre-war years to “cause the spoiling of Tofino.” Such plots threatened to close the Tofino telegraph and post offices, shifting them over to Stubbs Island, and abandoning all maintenance of the Tofino wharf.

Walter Dawley involved himself closely in such machinations, pitting the Conservative and Liberal factions of the area against each other. Never one to give up his schemes easily, Dawley clung for many years to his belief that a bustling community would grow up around him on Stubbs Island. In the early 1900s, this notion seemed entirely feasible to him, and his political allies bolstered the idea. In 1903 the like-minded James Redford, reassured him, “Not in our lifetime will there be sufficient business to establish a larger centre of population then you can acomadate [sic] on the island.”

Holding to the dream, in 1906 Dawley arranged for a survey of Stubbs Island, laying out a future townsite on the northeastern section of the island, in the area behind the store and hotel. The plan for this imagined community, officially registered, outlines several blocks, each with ten lots, intersected by a proposed grid of streets named Manson, King, Queen, and Cordova Streets. None of this ever became a reality. In 1916, Dawley submitted a scheme for a further subdivision, on a larger tract of land, covering the northwestern section of the island. These subdivisions attracted no settlers, no investors, no development. At some point Dawley must have realized the futility of such schemes, but nothing indicates that he gave up easily.

By the time World War I began, the Clayoquot cannery provided steady employment; the Ptarmigan mine, with its new roads and tramways at Bear River, buzzed with activity; and the copper mine at Sydney Inlet and the Kalappa and Rose Marie mines seemed full of promise. Even more exciting, a spanking new west coast steamer, the Princess Maquinna, made her first voyage up the coast in July 1913, promising a vastly improved service.

The war changed everything. The mines closed down or went into liquidation, Walter Dawley found his suppliers could not fill all his orders, being obliged to attend to military orders first, and the international market for furs collapsed. One by one, younger men in town enlisted and went off to fight: Charlie Dixson, the doctor’s son; Murdo MacLeod; Joe Grice; Arthur Grice; Arvo Haikala of the cannery; the schoolteacher Bert Drader; Burdett Garrard Jr.; Harold Sloman; Frederick Tibbs; the new police constable Robert Beavan. Lillian Garrard, having been encouraged by Dr. Raynor of the Methodist hospital on Stockham Island to study nursing, set off to England as part of the Canadian Army Medical Corps to nurse wounded soldiers. Jack Ross of Ahousat, the son of the Presbyterian missionary, enlisted, as did Harlan Brewster’s son Raymond. Over the course of the war all four of Fred Thornberg’s sons signed up: William Thornberg returned so badly wounded he died in Victoria in 1916; John joined the 28th Battalion and was seriously wounded.

On Vargas Island, Helen Malon wrote very little about the war in her diary, although it engulfed her life. When the guns of August 1914 sounded, the Malon and Abraham families had been on Vargas less than two years. Both Ted and Arthur Abraham enlisted immediately; September 1914 found them both at training camp in Valcartier, Quebec. Fletcher Cleland also enlisted at once; his attestation papers give his occupation as “rancher” and his address as “Westward Ho, Vargas Island”—the name he and his wife gave to their “ranch” on Ahous Bay. As the war progressed, other Vargas settlers signed up: Harold Monks, Frederick Sydney Price, Gerald Lane, George Anderson, the brothers Donald and William Forsythe and their uncle William, Harry Harris, the Hopkins brothers, Allan Carolan.

Freeman Hopkins and his brother Frank both enlisted in May 1916, leaving their young wives, Esther and Lillian, at Port Gillam on Vargas Island. When he left, Freeman instructed Esther to do business only with Walter Dawley. This led to a pathetic exchange of letters, with Esther valiantly explaining to Dawley how she could not hire a motor launch to come to Clayoquot to make her purchases. “I trust you will pardon me,” one letter ends. Unmoved, Dawley wrote to Freeman Hopkins at training camp in England, demanding he change his wife’s shopping habits. In the subsequent exchange of letters, Hopkins promised that his wife would comply, suggesting she may have been “induced by others in this respect.” In all likelihood, Esther Hopkins merely wished to purchase basic necessities on the island from local settler Helen Carolan, who briefly attempted to run a small store at Port Gillam. She gave it up a year or so after her young son Allan enlisted, aged only seventeen. “I understand young Carolan is going to Victoria this boat,” wrote Dawley’s assistant, Mr. Johnson, in a note to his boss on February 4, 1916. “His mother has at last consented to his joining up.” Perhaps to console herself, Helen Carolan started up a small school for ten children on Vargas Island in 1916. She received seventy dollars per month in salary; the two school trustees were Esther Hopkins and Harry Hilton. The school lasted less than two years. Dorothy Abraham later wrote that, “like the wharf which was swept away at the first big storm, [the school], in turn, was swept away by the first school inspector who paid a visit to the island.”

Francis Garrard noted in his memoirs how, “at the beginning of the war, there seemed to be a considerable amount of distrust between the Norwegians & the British element at Tofino, but later on after hearing of the sinking of many Norwegian vessels by the Germans, the former seemed to view matters more from the Canadian point of view.” The tensions in the town spilled over in an angry letter from James Sloman, published in the Colonist on November 19, 1915, defending Tofino against accusations of being “pro-German.” While admitting that in the early days of the war a few locals “who lacked…both brains and patriotism” made pro-German statements, he pointed out how “in Oct 1914, under the auspices of local Overseas Club, we called a patriotic meeting and raised $315 towards the patriotic fund; and since that time we have on different occasions raised toward the tobacco fund the following sums: $57, $45, $30, through the same agency, the Overseas Club.” Sloman stated that out of a population of seventy-five men over the age of eighteen, ten had already enlisted as volunteers. “It is unfair, un-British,” he fumed, “to rope, throw and brand a whole community for the actions and utterances of a few.”

On November 7, 1917, Helen Malon wrote in her diary: “Mrs G. [Garrard] came over in the morning to tell us about my darling Arthur. God Keep Him.” Arthur Abraham had died overseas. One letter survives from him to his mother, dated October 5, no year given, likely written from northern Europe. “It’s about time for another letter I think especially as I have not gone into the trenches this time… So far as I have discovered at present my duties when the battalion is in the trenches consist of (I touch wood) looking after the requirements of one horse.” With her two younger children and daughters Violet and Eileen, Helen Malon remained on Vargas for nearly two years following Arthur’s death, never again mentioning him in her diary. By 1919, the family spent more time in Victoria than on Vargas, and by 1921, according to Helen’s granddaughter Joan (Malon) Nicholson, the Malon house on Vargas stood deserted. Most other homes on Vargas met a similar fate.

Only a small handful of wartime letters from the local men who enlisted have survived. Some appear in Walter Dawley’s correspondence. “Jerry Lane and Harry Harris are now over in France in the thick of it,” Freeman Hopkins wrote in September 1916. That same month, Murdo MacLeod wrote: “I hope to live to see you & have a yarn about some of my experience since I left…That is if I don’t get knocked out before that. It’s the easyest thing in the world to get knocked to Kindom [Kingdom] come here…Writing under difficulties.” In a letter to his two younger sisters in 1918, Raymond Brewster wrote: “Well dears I expect to be away to France before very long…I’ll try to catch a nice little Kaiser for you.” In one of his letters, Freeman Hopkins asked, “When is this war going to finish, as I am ready for home-sweet-home,” a sentiment echoed by Murdo MacLeod: “Well we will be all glad when it’s all over & back to God’s Country again.”

When the war ended, the list of dead from Tofino and Clayoquot Sound included Arthur Abraham, Raymond Brewster, Donald Forsythe, Burdett Garrard, Joseph Grice, Arvo Haikala, John MacLeod, Frederick Sydney Price, Jack Ross, Frederick William Thornberg. The injured who returned included Murdo MacLeod, Wallace Rhodes, Jack Mitchell, Fletcher Cleland and John Thornberg. MacLeod had received serious facial injuries in 1916 at Courcelette and returned to the front, only to be seriously injured once again in 1917. Recuperating at Keighley War Hospital in Yorkshire, his astonishment only matched hers when he met Nurse Lillian Garrard from Tofino working on his ward.

Only two of the Vargas men who enlisted returned to live on the island following the war. Harold Monks returned and also Ted Abraham, bringing with him his energetic wife Dorothy. The Abrahams built a house near the Hovelaques, and Dorothy tried to come to grips with the isolation. In her book Lone Cone, she lamented how, with only her in-laws, occasional Indigenous visitors, and one male settler nearby, she had “no-one to see all my nice English trousseau.” Dismayed by the ugly masses of stumps on cleared land, yearning to play tennis on a groomed court, and hating to travel to Tofino over that “horrid piece of water,” she tried to imagine life on the island before the war, with some thirty hopeful settlers in residence. Their places now lay abandoned and “it was very pathetic to come across little clearings and houses with desolate gardens, which had been laid out with such care and hard labour.”

An era had ended on Vargas Island. In Tofino, the community regrouped and carried on.