Chapter 10: “Teeming with Riches”

The tantalizing possibility of finding rich mineral deposits gripped the imagination of many early settlers on Vancouver Island. “The West Coast lands teem with riches in the shape of gold, copper, coal, iron and other metals,” declared Dr. J.S. Helmcken of Victoria in a letter to the British Colonist in May 1899. While hope ran high for discovering all these valuable resources along the coast, nothing ever equalled the feverish dream of finding gold.

When the Cariboo gold rush ebbed in the mid-1860s, many of the miners who had come to seek their fortune stayed on in the new colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia. Some ventured up the west coast, encouraged by early rumours of gold and other minerals. In 1861, prospectors found small quantities of gold in San Juan Creek near what is now Port Renfrew, and others found copper in Barkley Sound. Four years later, John Buttle unwittingly launched the first rush of gold seekers into Clayoquot Sound.

Formerly a botanist at London’s Kew Gardens, Buttle took part in the Vancouver Island Exploring Expedition of 1864, led by Robert Brown and commissioned by Victoria business leaders to explore Vancouver Island and to search for viable mineral deposits. The following year, Buttle led another expedition at the request of the colonial government, then headed by the third and last governor of Vancouver Island, Arthur Edward Kennedy, after whom Kennedy Lake and River are named. As part of his mandate to explore and survey the west coast of the Island, Buttle was responsible for assessing the area in and around Clayoquot Sound. He left Victoria with a six-man party on the HMS Forward, and for the next two months they explored every inlet, bay, and river of the Sound. Buttle sent intermittent reports to his superiors in Victoria, which the Colonist eagerly reprinted or quoted. In April 1865, he reported that members of his party had found payable quantities of gold in the Bear (Bedwell) River at the eastern end of Bedwell Sound. Buttle then carried on with his explorations elsewhere in Clayoquot Sound and up at Nootka Sound, unaware that his newspaper report had set off a minor gold rush to the area. In August 1865, a group of some 200 avid prospectors set out to Bear River aboard the steamer Otter, angrily turning away Chinese gold seekers because, according to the Colonist, “feelings of antipathy to the Chinaman setting foot on white men’s diggings is too general.” But once the prospectors began panning in the Bear River, they discovered very little gold. They remained in the area only a week before returning to Victoria in disgust. The disillusioned men complained bitterly of being duped, accusing Buttle of being irresponsible, and the once enthusiastic reports in the Colonist now condemned Buttle as “not fit to command a cook’s galley, much less a party of exploration.” Soured by this experience, Buttle sailed to California, putting British Columbia behind him. Buttle Lake, in Strathcona Provincial Park, the oldest park in the province, bears his name.

Twenty years later, another burst of activity took place at Bear River. In September 1886 the British Colonist reported: “We learn that about a month ago 5 Chinese miners who came from a creek in Alberni Sound made a prospect on Clayoquot Sound, and found on Bear River, which empties into the sound, splendid prospects. The find is good enough to justify the Chinese to break camp at Alberni and 25 Chinese have also gone there.” The numbers quickly increased, and in December 1886 the Colonist reported that some eighty Chinese had built huts along the Bear River and intended to stay for the winter: “A boss Chinaman brought about $600 in gold dust from Bear River, and he also speaks encouragingly regarding future prospects.” Later the newspaper reported: “It is understood that a steamer has been chartered to take in another cargo of Chinese and supplies. It is regrettable, if the diggings are as rich as it is now supposed they are, that they should be exclusively controlled by the Chinese. Some of our white mining population should at once take a trip to the new field and make an effort to open it up.” Nonetheless, few Europeans ventured into the area, and mining experts who did go remained dubious about the prospects there.

In July 1887, the provincial minister of mines, John Robson, sent Captain Napoleon Fitzstubbs to Bear River to make an assessment of the situation. Fitzstubbs reported back: “From all I saw on Bear River…I am of the opinion that no remunerative discoveries of gold have been made there hitherto, and…there will not be hereafter.” That December all the Chinese, possibly driven away by the sudden death of one of their number, returned to Victoria, “bringing with them the most gloomy reports of their mining operations during the year, and say there is very little gold on the river, at least it does not pay to look for it.”

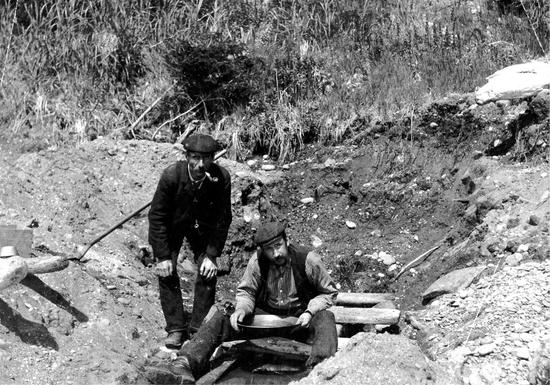

A decade later, hope ran high yet again in the Bear River area. Prospectors returned in numbers to try once more, staking new mining claims and working them more aggressively, now tunnelling and blasting the bedrock to get at the ore rather than sluicing for placer gold flakes in the sands of the riverbed. Promising findings of copper and silver and veins of gold-bearing quartz kept the excitement alive, with hundreds of men coming and going at Bear River in the late 1890s. This surge of activity saw a hastily constructed community called Port Hughes scramble into existence near the mouth of the Bear River. On August 22, 1899, the British Colonist described this little settlement as having “assumed very considerable proportions. It is to have a good wharf shortly, and is already the headquarters of 60 or more located mines, a score or more of which are being actively developed.” For a short while, Port Hughes became a regular stop on the coastal steamer route, and the place seemed so promising that former Victoria alderman Moses McGregor financed the construction of a fourteen-room hotel “which would not be out of place in any city.” This hotel would accommodate not only Bear River prospectors and miners, but others investigating their mining claims in the general area.

The enthusiasm for mining and prospecting throughout Clayoquot Sound and all along the west coast spread like wildfire in the late 1890s. Prospectors flocked onto the coastal steamers, heading north to try their luck. The Colonist described the scene aboard the Tees on April 21, 1897, the steamer en route from Clayoquot to Ahousaht and other stops: “With very few exceptions, every passenger was a prospector, with a formidable looking pack at hand’s reach.” Any whisper of a positive showing strengthened the determination of the miners and prospectors as they laboured on their claims, chipping and blasting into the rock. They fanned out all around Clayoquot Sound and along the coast, following rumours of good prospects and high-priced sales of properties. The Colonist never missed a transaction: “A good deal of interest is being taken in the West Coast mines, as witness the bonding not long ago of 2 groups of claims on Bear River owned by Chris Frank and Mr. Jacobson for $40,000 and $25,000 respectively. The lead on the Black Cap, which shipped 1 ton of ore by Tees on her last trip, is 3΄ wide and assays $67 a ton.”

With returns like these, small wonder nearly everyone in the vicinity became involved. Even the Presbyterian missionary at Ahousaht and the priests at the Roman Catholic missions began staking claims, hoping to strike it rich. On June 10, 1897, the Colonist observed that “Indians, klootchmen [Indigenous women], Chinamen, white men and in general every resident of Clayoquot is a prospector and a firm believer that a great future for that section as a mining country is not very far distant.” Filip Jacobsen, then Thomas Earle’s manager at Clayoquot, eventually held interests in about thirty claims, while Walter Dawley and Thomas Stockham also held a great many mining interests. From July 1898 onward, as the first official Mining Recorder for the area, Dawley knew every lump of ore and every ounce of gold removed from anywhere in Clayoquot Sound. By the end of that year he had recorded 114 mining claims, four of them placer claims. With such traffic through his store, he heard all the gossip and did a brisk trade with the miners. For a number of years around the turn of the century the store’s letterhead declared “MINERS’ SUPPLIES A SPECIALTY: A Full Line Constantly Kept in Stock.”

Although the Bear River/Port Hughes excitement did not last long, at its peak dozens of men toiled long and hard at their claims. At first they carried their ore out in haversacks, later by packhorse, along the rough fourteen-kilometre trail and over the seven rudimentary bridges they had constructed, extending from the claims high up in the mountains at the head of the Bear River, down to the mouth of the river. From there, the ore travelled to Victoria aboard the coastal steamers Tees or Queen City, and on to smelters at Ladysmith or Crofton on the east side of Vancouver Island, or to Tacoma in Washington. Americans took a keen interest in this mining boom, buying up a number of promising claims. On March 8, 1898, the Colonist reported: “One sale is that of the Crow group which Messrs. Jacobsen, Drinkwater and Peterson have disposed of to Spokane and Tacoma people for $20,000 cash. Another deal just made is the transfer of the BeShaklin claim owned by Stockham and Dawley, Clayoquot, for $10,000. This claim is situated on Sidney Inlet adjoining the Jones and Kincaid property.” The following year the newspaper declared that “the coast is overrun with American mining speculators looking for ‘good things.’”

Canadian speculators also rushed to invest, evidenced by the flood of reports in the Victoria newspapers. In December 1897: “Leslie Jones, who has just returned from spending 8 months in that mineral belt of the Island, states that all the way from Sidney Arm to Hesquoit, a distance of 6 miles [10 kilometres], is staked out. Mr. Jones is associated with Messrs Morris and C. E. Cooper, of this city, in the ownership of a number of claims on Bear River, besides 6 at Hesquoit and 3 more, which are a continuation of the Jones and Kincard [Kincaid] group on Sidney Arm.” The same Leslie Jones wrote to Stockham and Dawley from one of his claims in mid-1897, requesting that they send a case of rye whiskey on the next boat. Such orders arrived often from men marooned at their isolated claims, requesting booze, blasting caps, dynamite, tobacco, “prospecting shoes,” and food.

The mining claims in Sydney Inlet turned out to be the most promising and active in all of Clayoquot Sound, championed in the late 1890s by the irrepressible prospector James Jones, known as “Black Jones.” His cheerful letters to Walter Dawley brim with optimism and good humour. “Excuse this writing,” he announced in one letter from Sydney Inlet in July 1898, “my only table is a gold pan.” By then, Jones and his partner, James Kincaid, had been keenly working their claims on Peacock Mountain, alongside Stewardson Inlet on the west side of Sydney Inlet, for nearly a year. With a team of a dozen or so men they had erected cabins and a blacksmith shop and driven at least one tunnel eighty metres into the rock. Their sacks of ore travelled out to the smelters on the coastal steamers, sometimes picked up from Fred Thornberg’s trading post at Ahousaht. Thornberg grumbled in his letters about having to load what he called “Jones oar” from freight scows and canoes to the steamer, a task he loathed almost as much as loading barrels of dogfish oil. Delighted with his initial findings, Jones became known as one of the best prospectors in the district, praised by the newspaper in 1897 for finding “the prettiest peacock copper seen in Victoria in recent months.”

Such reports kept optimism alive among the miners and prospectors as they laboriously made trails to their claims and chipped their way into the rock. They ardently followed rumours of good prospects and stories of high-priced sales of properties. They christened their claims with evocative names like Iron Duke and American Wonder on Tranquil Creek; Indian Chief in Sydney Inlet; Iron Cap and Kalappa on Lemmens Inlet; Brown Jug at Hesquiaht Lake; Jumbo on Deer Creek; Good Hope on the Trout (Cypre) River. The Bear River gold rush inspired names like New York, Seattle, Corona, Castle, Belvedere, King Richard, and Galena. In 1898, Clayoquot Sound boasted thirty-two prospects enjoying varying degrees of activity, with only a very few, including the Rose Marie on Elk River above Kennedy Lake, showing much promise for future gold production.

While these small-scale endeavours continued in Clayoquot Sound, the massive gold frenzies of the Klondike and Alaska captured the world’s imagination with dramatic tales of fortunes won and lost. Any mention of gold, anywhere, stirred up eager interest. In June 1899, word reached Victoria that Carl “Cap” Binns, the man who carried the mail from Ucluelet to Clayoquot, had discovered gold flakes in the black sands of Wreck Bay (Florencia Bay), just south of Long Beach. Binns discovered the gold accompanied by Klih-wi-tu-a, or “Tyee Jack,” who may have been first to spot the gold. A new rush of mining claims ensued along the three-mile beach of Wreck Bay: the Presbyterian missionary in Ucluelet, Melvin Swartout; the officers of the steamer Willapa; and the skippers of several sealing schooners visiting Clayoquot all staked claims, and the Colonist declared that if the reports of gold proved true, it existed “in quantity sufficient to bring 10,000 miners to the field in half a year.”

Prospectors found the flaky, floury, very fine gold of Wreck Bay difficult to extract from the sand; while some boasted exceptional hauls of $4.50 a pan, others came up entirely empty owing to the patchy distribution of the gold on the beach. Nevertheless, miners worked all that summer using rockers and pans, and enticing reports kept surfacing of how much gold travelled out on the coastal steamers, at times over a thousand dollars’ worth in one shipment. Winter storms brought that first season to an end.

James Sutton of Ucluelet had staked claims at Wreck Bay immediately after the initial discovery. He and his brother William owned Sutton Lumber and Trading Company in Ucluelet, and both became involved in the excitement at Wreck Bay. James formed the Ucluelet Placer Company in partnership with a “San Francisco mining man,” Mr. T. Graham, and in the spring of 1900 he hired twenty-five men to construct a water flume in twelve weeks. According to the Colonist of July 1, 1900, this two-kilometre-long flume cost $10,000 and used 80,000 board feet of lumber, extending from a dam on Lost Shoe Creek to the beach, bringing the fresh water essential for sluicing the placer gold from the sand. Salt water could not be used because it held sand and because wave action made it difficult to obtain. Meanwhile, other methods of gold extraction came into play, with several ingenious machines at work on the beach. On September 30, 1900, the Colonist reported that the steamer Willapa had “brought $1700 in dust from Wreck Bay. This was taken from the Sutton properties on a 10 days run of a small gold-saving machine. Two larger machines are being installed, and when these are put to work the output will be greatly increased.” By early October the Sutton and Graham flume sluiced its first gold, but by the end of that month high tides and storms washed out whole sections of the flume, forcing operations to shut down for the winter. The Sutton syndicate claimed to have recovered $12,000 in gold from the year’s production, prompting some prospectors to begin looking at the sands of Long Beach for similar returns, but lack of promising “colour” there discouraged them.

In April of 1901, with the flume repaired, Sutton and Graham’s hydraulic machines recovered an average of $450 worth of gold flakes a day, but foul spring weather and high tides forced constant closures. By the following year, due to the perpetual interruptions caused by tides and storms, claim owners were looking to offload their properties. John Eik, G.R. Talbot, and Filip Jacobsen sold their Wreck Bay Mining Company to a Seattle real estate agent, Mr. Starbuck, for a reported $60,000. Sutton and Graham sold theirs to two San Franciscans, Mr. Riffenburg and Dr. Gunn. By 1903, with most miners having given up on Wreck Bay, Tofino store owner Sing Lee leased the claims and hired a few of his fellow Chinese to rework the tailings to recover what gold they could. In the three years of the Wreck Bay gold rush, an estimated 35 to 40 thousand dollars’ worth of gold emerged from the black sands of the beach. How much Sing Lee and his Chinese workers gleaned remains a mystery, but they persevered. According to the Colonist in August 1903: “The purser [of the Willapa] brought 53 ounces of dust which was shipped to Victoria by Sing Lee.”

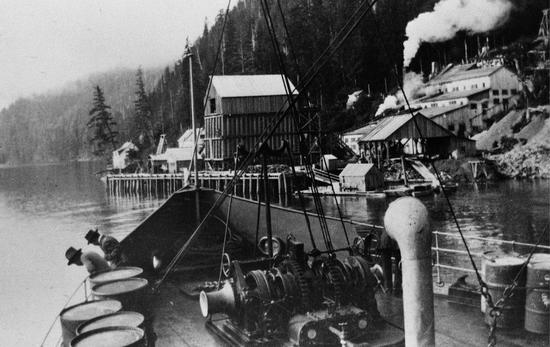

Within Clayoquot Sound, the Sydney Inlet claims eventually developed into the most successful mine in the area, the Indian Chief Mine, on the property originally worked by James Jones and James Kincaid. After their initial efforts, unable to finance further development, Jones and Kincaid sold out in 1899 to Edgar Dewdney, BC’s first Lieutenant Governor, and his Dewdney Canadian Syndicate based in England. The new owners added five nearby claims to their holdings and carried out development work until 1904. The mine then fell idle until 1907, when the Vancouver Island Copper Company reopened it and built an aerial tramway extending from the mine entrance, high on the steep side of the inlet, down to a wharf they constructed on the foreshore. From there, ore could easily be loaded onto ships for transport to the Tacoma smelter. In November 1907, Father Charles Moser noted in his diary: “My first Mass at Sidney Inlet, a copper mining camp, where quite a few Indians are employed.” In 1908 the Tyee Copper Company purchased the property and began to develop it, initially hiring some twenty-five men to work the mine and to operate the small sawmill providing pit props and shoring. By 1909, thirty-seven men worked at the site.

James Jones followed all these developments in Sydney Inlet with keen interest, even writing to inquire about his former mining claims from South Africa after he volunteered to serve in the Boer War. Throughout subsequent misfortune and ill health, Jones’s heart remained fixed at his old mining claim. He returned to Sydney Inlet a couple of times, but his health failed and in June 1911, James Jones took his own life, shooting himself in Beacon Hill Park in Victoria. He never saw the enduring success of his copper mine. The man who discovered “the prettiest peacock copper” on the west coast lies buried in an unmarked grave in Ross Bay Cemetery in Victoria.

After a hiatus of several years, activity had increased at Sydney Inlet by 1916 as copper prices soared during World War I. The mine came back into action under the name Tidewater Copper, managed locally by Silas P. Silverman. A 100-ton-per-day concentrator helped improve production, and despite a short-lived strike at the mine in 1918, by 1920 it was producing 300 tons a day. Father Charles often mentioned the mine in his diary during those years, mostly because the coastal steamer so often faced lengthy delays there, loading copper concentrate and unloading large amounts of cargo. With declining copper prices, the mine closed down in 1923, putting sixty miners out of work and leaving many unpaid bills.

In the mid-1930s, Japanese investors purchased the mine and production resumed. With the onset of World War II, suspicions circulated locally that the Japanese in Sydney Inlet were using the mine as a front to build a submarine base and other facilities. The mine closed again in 1939. BC’s Ministry of Mines and Energy reports that between 1904 and 1939 the overall production of the mine came to 722 ounces of gold, nearly 54,900 ounces of silver, and 2.43 million pounds of copper.

During the early years of World War II, members of the Fishermen’s Reserve ripped up rail tracks that had been part of the mine and took them to the air base being constructed at Ucluelet, where they were re-laid and used to haul Canso planes out of the water on a dolly. A Fishermen’s Reserve veteran later recalled being ordered to go to Sydney Inlet and blow up the mine. “I remember the mine was way up on the hillside…There was a big powder magazine with big vents in it. So somebody said, well, there isn’t any use blowing us all up, so we plugged the vents with rocks and when she blew, the ship was about half a mile down the inlet on anchor, and these rocks went out like cannonballs…big plumes of water all around the boat as these rocks crashed.”

Although the Indian Chief mine at Sydney Inlet became the most productive mine in Clayoquot Sound, interest in the Bear River area persisted over a longer stretch of time—as gradually the name “Bedwell” replaced “Bear.” The area fell silent following the excitement at the turn of the century, marking time until 1912. That year, a group of English investors purchased the mining properties known as Big Interior and Ptarmigan, located on the summit far up Bedwell River, and established Ptarmigan Mines Ltd. to work the rich copper ores of the properties. The company set up a camp at the mouth of the river, and for a couple of months in the summer of 1914, work began in earnest: developing and extending a wagon road along the steep terrain by the river, building a large new bridge, and starting work on at least six tunnels. Materials, including great spools of steel cable, arrived for a planned aerial tramway at the head of the inlet. It was never built. With the outbreak of war in August 1914, the men left to enlist, the management returned to England, and everything was abandoned. The same fate befell the Rose Marie mine, and the Kalappa mine in Lemmens Inlet. Owned by John Chesterman and others, this mine had shipped out 1,500 tons of ore in 1913; the war brought all activity to an abrupt end.

When a Ptarmigan Mines engineer came to investigate the possibility of reopening the mine in 1919, he found much had been damaged or stolen, and the hard-won wagon road was in serious disrepair. The company attempted some work in the late 1920s, but it did not amount to much. In his book Jack’s Shack, Jack Crosson described the mine area following his visit to Bear River in 1931 as a member of the Hydrographic Survey:

Small flurries of mining activity continued in the vicinity of Bear River. Bill Bond came to Tofino in 1922 to work on the You Creek Mine, a set of four mining claims near the Ptarmigan Mine, owned by J.B. Woodworth of Vancouver. Bond took freight to the head of Bedwell Inlet by boat, then trekked twenty kilometres along the trail up the river to the mine, with packhorses carrying the freight. The return journey sometimes saw the horses’ rawhide packs laden with gold concentrates extracted by a small cyanide mill at the mine. In the end, this mine, like so many others, failed to become viable, partly because of the onerous challenges of transport. By 1933 it lay abandoned.

In 1933, Alfred Bird and his associates staked their claims on a rich vein of gold at Spud Creek, near Zeballos Inlet on the west coast of Vancouver Island, eighty kilometres northwest of Tofino. Another rush for gold ensued, centred on the hastily created boom town of Zeballos. During its first hectic decade, the Zeballos gold rush saw over $13 million worth of gold, at $35 an ounce, extracted from a number of mines in that area. Such rich findings led to a renewed surge of interest in the potential for gold at the Bedwell River mining properties. In 1938 the Pioneer and Bralorne mining companies opened mines there, the Musketeer and Buccaneer. They worked for three years just prior to and in the early years of World War II. The original wagon road and trail leading upriver underwent considerable improvements, and hopeful miners once more headed to the mines.

Walter Guppy described the scene at Bedwell River in his book Wet Coast Ventures: “There was a grocery store and a flophouse where lodgings, meals and bootleg booze could be obtained at the beach, and a truck and taxi service to the mines. The madam from Zeballos even paid a visit with a view to establishing a branch facility.” Miners flew in and out from Vancouver on float planes that landed near the Tofino dock, overnighting in town before heading to the mines. In his unpublished memoirs, Sid Elkington, who owned a store in Tofino and acted as agent for Canadian Airways, recalled: “Pilot Tom Laurie would call on the radio; advise me that he was over Kennedy Lake and descending…and advise me to bring a funnel out to the float, so he could pour off his passengers. This would indicate to me that he was bringing back a load of miners, who had been in Vancouver to celebrate, blow their wages and were returning, badly hung-over, and quite unsteady on their feet, or worse than that.” But as with the earlier Bedwell (Bear) River gold rushes, this one also ended in war. “It was said locally that Bear River…was jinxed,” wrote Walter Guppy. “Every time a boom started a war broke out to end it; first the Boer War, then the First and Second World Wars.”

The industry destined to bring the greatest riches, the most activity, and the most notoriety to the west coast began in an unspectacular manner when Captain Edward Stamp, financed by British investors, established a steam-powered sawmill at Alberni in 1860–61. He received a 6,070-hectare timber grant from Governor James Douglas and reportedly “purchased” the logging rights to Barkley Sound from the Tseshaht people for “twenty pounds sterling, fifty blankets, a musket, molasses, food and trinkets.”

By August 1861, William Banfield, agent to the Colonial Secretary, informed Douglas of 14,000 board feet of lumber being cut at Alberni Settlement every day; when better machinery arrived he believed the daily production should rise to 50,000 board feet. Head logger Jeremiah Rogers supervised operations there for four years as his crew fed logs to the mill; his name lives on at Jericho Beach in Vancouver where he later worked at what became known as “Jerry’s Cove.” Increasing costs and growing competition from mills in Washington and Oregon saw the Alberni sawmill close in 1864, after exporting 35 million board feet of lumber to markets in Britain. Some of the lumber cut at the Alberni mill found its way to the 1862 World’s Fair in London; the Colonist announced this as a sign of “what Vancouver Island can do in the tree-growing department.”

By the 1880s, other smaller mills began operating in Barkley Sound and in scattered locations up and down the coast, cutting and milling for specific local markets. Early settlers highly valued milled wood, which often proved difficult to obtain. Sometimes shipwrecks obligingly cast up loads of lumber on the coast, free for the taking, but hardly a reliable source.

In October 1894, Bernt Auseth, originally from Trondheim, Norway, pre-empted 56.6 hectares at Mud Bay (Grice Bay). A month later, fellow Norwegian Thomas Wingen pre-empted the adjacent property. Highly inventive men, Auseth and Wingen together built a small waterwheel-driven sawmill at the mouth of Kootowis Creek on Auseth’s property. They laboriously ditched and dammed a slough, using lumber to make the dam, constructing it so that the force of the water pushed the joints together to make it tighter and stronger. Then they made a waterwheel, nine metres in diameter, using yew wood for the cogs and crabapple for the pinions. Next followed the axle, created with squared fir, tapered at the ends and strapped together with scrap iron. For bearings they scoured the beach for big round stones, which they hollowed out, fitting the axle into them, and the whole apparatus ran smoothly with generous lubrications of dogfish oil. The sawmill could handle logs up to 1.25 metres in diameter on the hand-cranked carriage that fed the saw. When Wingen and Auseth finished an order of lumber, they bound it into a raft, set a 3.6-metre-long sailboat on top, and sailed with the tide down the inlet for delivery. Many of the earliest homes of settlers in the area used lumber from this unique mill. After a number of years of running the mill, Auseth left the area. Tom Wingen acquired Auseth’s land and continued operating the mill until he moved to the emerging settlement at Tofino.

In 1883, James and William Sutton came to the west coast. Already involved in mining and sawmilling at Lake Cowichan and Deep Bay, the brothers established themselves at Spring Cove, near Ucluelet, and built a sawmill. Ten years later, with capital of $100,000, they incorporated as Sutton Lumber and Trading Company, and as they became more established and successful they began acquiring a vast number of timber leases in the Kennedy Lake area, and later on Meares Island and elsewhere in Clayoquot Sound. In 1903 they sold shares in their company to the Seattle Cedar Lumber Manufacturing Company, then expanding into Canada. With the American company financing the project, the Suttons began constructing what would become the biggest cedar mill on the west coast, at Mosquito Harbour on Meares Island. The site provided ample fresh water to create the necessary steam to run the mill, and its protected bay was deep enough to accommodate large ships that would carry away the finished products. By 1905, 150 workers laboured to complete the ambitious mill, with a wharf and small townsite at Mosquito Harbour. The total cost of this immense project reached $460,000. “Preparations are in active progress to commence construction of logging roads, mills, wharves, etc., plans for machinery are in preparation, and this promises to become one of the largest and most successful lumber enterprises in BC,” trumpeted the Colonist in November 1905. “The company has a capital of many millions, a disposition to spend wisely but freely, and abundant successful experience in the lumber position. The fact that they will cut, carry and dispose of the lumber in a market which they already control makes their position an exceptionably strong one.” In June 1906 the newspaper claimed the mill would employ “400 or 500 white men,” that it would ship two or three loads of wood each week to international markets, and that this mill would be “the very largest in the manufacture of cedar in the Dominion.”

Loggers began felling immense red cedars in nearby Warn Bay to be milled into shingles and lumber for markets in New York and New England. These “handloggers,” as they were called, chose trees growing near the water’s edge so the logs would fall or skid into the water, where they would be boomed and later towed to the mill site. Once the loggers selected a tree, they cut smaller trees to fall crossways and downslope from the bigger tree, ensuring that it would have a cushion to fall on and a surface to skid along down to the saltchuck. When they began work on the bigger tree, the loggers cut notches into the trunk, facing in the direction they wanted it to fall, and inserted springboards into the notches. Standing on the boards, they cut another deep notch, or undercut, after which they inserted additional springboards on the opposite side of the trunk. Then they went to work with the two-man, 3.3-metre crosscut saw. It could take two men a full day to cut one tree. Accuracy was vital; if the tree missed the pre-cut skid trees, it would hang up before reaching the water’s edge. If this happened, loggers could spend countless hours using peavey poles and Gilchrist jacks to force the tree into the water. Once the tree had fallen, the loggers then faced the chore of limbing it and cutting it into manageable lengths. When enough logs had been cut and boomed, a tug towed the boom to the mill site.

The Mosquito Harbour mill began operations in November 1906, producing “500,000 shingles and a large quantity of lumber a day,” according to the Colonist. Workers lived in the townsite near the mill in houses provided by the company, and they even had their own Mosquito Harbour post office to serve them. By May 1907 the mill had over four million board feet of lumber ready for shipment. The future seemed rosy—but then catastrophe struck. Saltwater teredos (Teredinibacter turnerae), or shipworms, had infested the entire inventory of logs—12 million board feet—in the booms near the mill. Ranging in length from 7.6 to 90 centimetres, these teredos had bored into the logs, feasting on the cellulose and honeycombing each log with tiny passages, degrading its strength and rendering it useless for milling. The company laid off all the loggers, but the mill continued processing logs untouched by the pests. By July, teredos had infested the wharf pilings so badly that the wharf collapsed, throwing “two to three million board feet of lumber and shingles into the water,” according to the Colonist of July 12, 1907. Workers scooped up the bundles of shingles and the lumber and loaded them onto the freighter Earl of Douglas, which had arrived to carry whatever it could of the salvageable lumber and shingles to the eastern United States. The vessel carried four million board feet of lumber around Cape Horn to New York, arriving in November 1907, only to find that a financial collapse had caused a dramatic slump in the lumber market. This broke the Mosquito Harbour mill, and it closed. Hopeful that a profitable market for cedar products might arise in the future, the company continued to maintain the mill, going so far as to replace its pilings with concrete foundations in 1924, and for many years hiring Jacob Arnet as caretaker to look after the site.

In 1931, twenty-four years after it closed, Jack Crosson visited the mill. “We discovered Mosquito Harbour and what was left of a large wharf and shingle mill. The only indication of the wharf was at low tide when long rows of piling could still be seen. They were eaten in half by teredoes…The upper part and decking were long gone, but the lower third of the piles stood in lines in the mud, showing their pointed ends skyward. The remaining part was just a shell as the inside was honeycombed by the teredoes.” Crosson and his companions went into the engine room, finding everything in good condition, and they examined the six shingle-making machines, all seemingly in perfect order. The main building had no leaks, and all the windows remained intact. “The Americans had built a row of nice homes for their workers. We went into one after fighting our way through the young alder saplings, ferns, small trees, and other bushes. The house was well built and there was no leaky roof. All the windows were in and none broken. You could scarcely see the house next door through the West Coast jungle, although it was not that far, about twenty-five feet [7.5 metres]. I don’t know what has happened to the sawmill and cottages since then.”

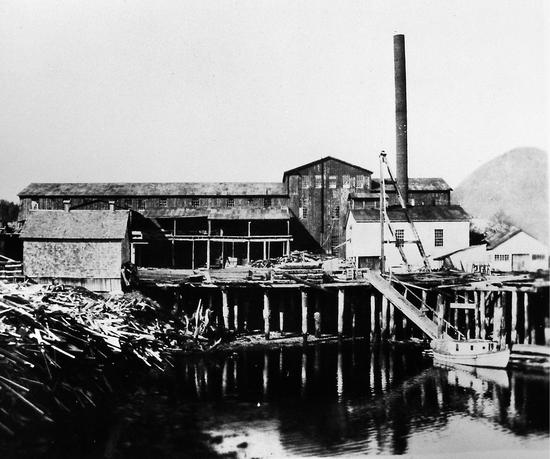

Ten years later, in 1942, the Gibson brothers from Ahousaht received a federal contract to dismantle the machinery at Mosquito Harbour mill and dispose of it for war use. The Gibsons definitely knew their way around sawmills, having been involved in logging and mills for many years. Their father, William F. Gibson, had been active on the coast since before World War I, coming and going seasonally, harvesting wood for various markets, and encouraging settlers in the region. Gordon Gibson joined his father in Clayoquot Sound in the summer of 1916, helping to fell and skin logs for telephone poles, and the following summer found them at Trout (Cypre) River, working on a contract to harvest “ships’ knees”—the large knee-shaped roots used for right-angle joints in wooden sailing ships. That work continued the following year, at the head of Herbert Inlet. All four of Gibson’s sons, John, Clarke, Earson, and Gordon, became involved in the family enterprises, turning their hands to any job that would make money. They fished; drove piles for docks, wharves, and booming grounds; transported goods; built docks and canneries; and towed log booms. By 1918 the Gibsons were cutting massive spruce trees as fast as they could under the terms of the new Aeroplane Spruce-Cutting Act, which issued special permits to cut spruce on public or private lands for aircraft construction. When the war ended, the Gibsons found themselves with a lot of spruce on their hands. They moved their operation to Ahousaht and built a small sawmill on the west side on Matilda Creek, initially to mill their leftover spruce into oar stock. A bunkhouse for their staff followed, and a home for themselves. In 1920, William Gibson, in partnership with Tommy Atkins, established his Gibson Lumber and Shingle Company, beginning a powerful family dynasty. Renowned for their risk taking and roustabout living, the Gibsons’ reputation grew, year by year.

Before William Gibson established his mill at Matilda Creek, John Darville had arrived on the west coast and set up his own small sawmill. Hailing from Seattle, where he worked as a pattern maker in a foundry, he built a water-powered mill at Calm Creek (Quait Bay) on the mainland behind Meares Island, about thirty-two kilometres from Ahousaht. With his sons Roy and Fred and one other helper, Darville produced lumber to order, establishing himself as a trustworthy and respected figure on the coast, able to turn his hand to anything. The Darvilles also built fish boats, and Fred developed the technique of inserting refurbished car engines into boats. John leased his mill to Fred Knott in the late 1930s and moved to Tofino, where he continued building boats. When his beloved mill burned down in 1939, he returned to Calm Creek and tried single-handedly to rebuild it, without success.

In 1926, following the success of the Whalen brothers’ pulp mill at Port Alice, Sutton Lumber came up with the idea of building a pulp mill, in conjunction with Crown Zellerbach, at the mouth of the Kennedy River. The plan included damming the river to raise the level of Kennedy Lake by fifteen metres to produce enough power to run the operation. This grandiose proposal came forward at the same time as, and possibly in conjunction with, an equally ambitious scheme for a west coast rail link. A proposed branch line linking Alberni to the coast would service the future pulp mill and allow the company to log the area by rail, particularly the flat land along the peninsula between Ucluelet and Tofino. Survey crews arrived to assess the feasibility of the pulp mill, but nothing came of this scheme—in part due to the financial collapse of 1929. Similarly, plans for a proposed hemlock sawmill at Mud Bay came to nothing. The plans for a railway never extended beyond the drawing board.

The west coast of Vancouver Island consistently attracted industries, ambitious projects, and people with grand dreams. Over many decades, schemes for mills, for mines, even for settlements, often in highly unlikely locations, have flourished and faded. The harsh realities and challenges of living and working on the coast have defeated many enterprises and undertakings, sometimes after years of persistent, back-breaking effort. Countless quiet inlets, bays, and mountainsides bear traces of broken dreams and abandoned ventures. Yet whatever the odds of making good, the coast has consistently drawn optimistic people willing to work hard, convinced they will succeed. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the settlers arriving on the coast came with high hopes, encouraged by the abundance of the sea and all the apparently empty land, so readily available to them. They looked to make a fresh start and they were determined to remain.