Chapter 6: Enter the Missionaries

By the time Charles Seghers returned to Hesquiaht, he had a new role and a clear purpose. Now bishop of Victoria, Seghers had decided to establish a permanent Roman Catholic mission on the west coast of Vancouver Island, and he had chosen the powerful and dynamic Father Augustin Brabant to be the first resident missionary. The two men set out from Victoria in April 1874 on the sealing schooner Surprise with one goal in mind—to determine the location of this future mission.

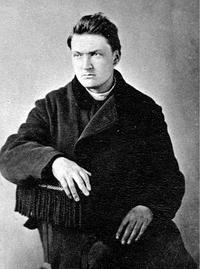

Like Seghers, Brabant had been born and educated in Belgium. Since arriving in Victoria in 1870 he had served as a parish priest, all the while yearning for greater challenges. Buoyed by his impressive physical strength, and inspired by the ascetic and stubborn Seghers, Brabant, from the outset, proved himself dedicated, tireless, and ruthlessly determined. In his world view and that of his bishop, the Indigenous people of the coast lived as pagan savages, doomed to an eternity in hell unless saved by the one true religion. Propelled by their immense force of will and by an absolute certainty that their religion must be imposed on the Nuu-chah-nulth, the two men never for one instant doubted their actions.

Their initial missionary voyage lasted a month. They travelled hundreds of kilometres, stopping in as many villages as possible, all the while expanding their religious ambitions. Despite a few setbacks, and despite a decidedly lukewarm response from some of the Indigenous people they met, they judged that, on balance, they had been welcomed. On more than one occasion the people had gathered in considerable numbers to hear the priests speak, which they did through interpreters and also by using what they had learned of the language. In several locations, the locals greeted them with ceremony and civility, even with enthusiasm. At Kyuquot, they erected a seven-metre-high cross on a small island to mark the arrival of Christianity. Everywhere they went, the two spoke vehemently against traditional beliefs; they taught people to make the sign of the cross and to repeat prayers and hymns in their own language. On this first trip, according to Brabant, he and Seghers succeeded in baptizing nearly 800 people in total: 80 children in Barkley Sound, 93 at Clayoquot (Opitsaht), 135 at Ahousaht, 177 at Kyuquot—and more. Heartened by these numbers, Brabant and Seghers resolved to return as soon as they could, and five months later they headed up the coast again.

The second missionary trip proved challenging from the outset. Having left Victoria on September 1, 1874, aboard the schooner Surprise, they soon realized that the captain, Peter Francis, was drinking heavily. With the help of the mate they attempted to confiscate the captain’s liquor, but he still managed to hit a sandbar at full tilt when they entered Pachena Bay seeking anchorage. A short while later they encountered, according to Brabant, “a canoe from Victoria with a supply of whisky,” and hard on its heels the gunship HMS Boxer heading into Pachena village, where one of Captain William Spring’s trading posts was located. On board the Boxer, the newly appointed superintendent of Indian Affairs, Dr. Israel Powell, on his first tour of the west coast, discovered everyone in the village “beastly drunk.” Reporting this event, the Colonist stated, “The Indian Commissioner expressed his grief, and they promised to amend.”

Brabant and Seghers parted company with Captain Francis and the Surprise at Ucluelet, continuing their journey north by canoe, three aboriginal men paddling. With heavy seas breaking over the bow, soaking their provisions of flour and biscuit, they made their way to Opitsaht. There they discovered that HMS Boxer stood at anchor just ahead of them in the lee of Vargas Island, but paying it no heed they finally made camp on Flores Island. Twice in the night they were awakened, first by some Ahousahts inviting them over to the village and secondly by a group of Hesquiahts, en route to Ahousaht, wondering who these strangers were. Waking in the morning rain, they paddled drearily on toward Refuge Cove (Hot Springs Cove), arriving late that afternoon. Again they found HMS Boxer ahead of them and at anchor, and with many visitors from neighbouring tribes “the place presented quite a lively appearance. A number of junior officers and blue-jackets were on shore.” Despite being warned by the Boxer’s steward against travelling further by canoe, the two clerics refused assistance—though they did accept provisions—insisting they would continue. The following day, through heavy seas and with a dismally seasick crew, they came ashore for lunch at Home-is, an encampment on the outer shore just north of Estevan Point, before doggedly continuing toward Friendly Cove in Nootka Sound.

“There, to our horror,” wrote Brabant, “we again found the Boxer at anchor.” Travelling in tandem with government authorities aboard a gunboat had not been part of their original plan. But the steward of the vessel again approached them with an invitation to come aboard, and this time Brabant and Seghers decided to continue their journey on the gunship. The Boxer’s crew hoisted their canoe on board, accommodated their paddlers, and for two days the missionaries travelled in comparative comfort. Reaching Kyuquot, the paddlers and the priests headed for shore and set up camp in an unoccupied store belonging to Captain Spring.

Over the next few days, Brabant and Seghers travelled to scattered encampments and villages around Kyuquot Sound. A dead whale upstaged their arrival at Nuchatlat; the carcass had drifted ashore and no one had a moment for these cassocked visitors. With their “houses full of blubber” being rendered to oil, “the whale was uppermost in [the people’s] minds.” They found better reception a day or so later when the Mowachaht tribe greeted them “with fervor and zeal.” Following this, they headed down the coast to Hesquiaht in a canoe manned by the Mowachaht chief and eleven of his men, the most exciting ocean voyage yet, described by Brabant in his classic phrase “the sea ran mountains high.” Off Perez Rocks, they met a Hesquiaht canoe “crowded with young men” coming to greet them, and “a regular race between the canoes took place,” with the two large dugouts continually losing sight of each other, rising on huge crests only to descend to “the abyss of the ocean.”

At Hesquiaht, according to Brabant, “The Indians were full of joy to see us once again.” Their previous visit to Hesquiaht in the spring had been similarly positive, despite the disturbing presence of the scaffolds where John Anietsachist and Katkinna had been hanged five years earlier, following the John Bright incident. Brabant later recalled seeing more evidence of the John Bright at Hesquiaht: a signboard from the vessel mounted above one of the houses. It read Neminem Time—Neminem Laede, meaning “Be afraid of nobody—hurt no one.” Brabant and Seghers stayed several days at Hesquiaht, busying themselves teaching “the Lord’s Prayer, Hail Mary, the Creed, Ten Commandments and Seven Sacraments, all of which the Indians learned with much zeal.” The evident goodwill in the village led the decisive Bishop Seghers to conclude then and there that Hesquiaht would be the location for the first coastal mission. Not only had the people warmly welcomed the priests, but this central location seemed ideal for reaching out to other tribes on the coast. Having proposed this notion to the assembled chiefs of the tribe, the missionaries began negotiating for land where mission buildings would be erected. “We were informed, in the presence of the whole tribe, that land would be given for Mission buildings and other purposes and that we could have our choice as to locality.”

The Hesquiaht chief and “a large crew of young men” escorted them to Ahousaht, but Brabant and Seghers found their reception at this next stop less positive. The Ahousaht chief refused to meet them, and most of the local people were busily employed at their various salmon rivers, laying in fish for the winter supply. At the bishop’s insistence, many of these Ahousahts were ordered back to listen to his religious instruction, only to face “a sharp reprimand” from him when they tried to leave that same evening. The following day found Seghers and Brabant at Opitsaht, where, to their chagrin, the chief kept them waiting. “His Lordship, the Bishop of Vancouver Island, and one of his priests were told to go outside,” Brabant wrote in astonishment. “The Chief of the Clayoquots could not transact any business with them till he had finished eating his breakfast!” Having eventually granted the missionaries an audience, the chief agreed to assemble his people to listen to them preach, and afterward they baptized four children. The priests then asked the chief to provide an escort for them down the coast to Ucluelet, but he deflected this request, suggesting instead that they go up Tofino Inlet to his salmon station. From there he would escort them across the peninsula to Long Beach, where they could find a canoe at one of the outer fishing camps and travel to Ucluelet.

Having agreed to this, Brabant and Seghers initially found themselves marooned at the Tla-o-qui-aht chief’s salmon fishing encampment, a low and smoky dwelling dominated by the powerful smell of fish, where they “could not put a foot except on or over dissected salmon or salmon roe!” Their discomfort and impatience grew, and eventually they convinced the chief to escort them across the peninsula to Long Beach. Once on the outer coast, they found the sea running very high and no canoe could be launched. The chief returned to his home on the inlet, promising to return the following day, and the two missionaries pitched a tent and determined to wait. The following day, the easterly wind and high surf made travel impossible. Another day passed, another night, and still the wind did not abate.

Perhaps unnerved by the visit of a bear to their encampment, and certainly tired of waiting, Seghers imperiously declared they must abandon the idea of travel by water; they would walk the length of the beach and then find the aboriginal trail to Ucluelet. “The Clayoquots hardly approved of the idea, but promised to take our baggage to Captain Francis’ house as soon as the weather would permit.” Even Brabant inwardly questioned the wisdom of this decision, recording that the bishop “ordered me to prepare some provisions, which I did with reluctance.” Two Kyuquots, likely slaves of the Tla-o-qui-aht chief, accompanied them and carried the provisions. That first night the rain poured down, and the following morning they set out again. As the earliest chronicle of Europeans hiking through the bush near Long Beach, Father Brabant’s account of what ensued would never qualify as promotional material for wilderness adventure in and around Tofino. “We took to the bush,” Brabant wrote, “intending to make a short cut of a projecting point. After struggling about a couple of hours through the thick salal, we came to the Indian trail.” Hours later, their trail emerged on the beach they had left that morning. Brabant’s account continues, describing how he and Seghers, with woefully inadequate supplies, spent another day stubbornly thrashing through dense forest in the pouring rain, trying to find the trail. “The two Kyuquots,” Brabant recorded, “began to show bad will, and insisted on going back to the beach, which we did.” They camped out, miserably wet and cold, and their large campfire spread to nearby trees, burning holes in Brabant’s boots and clothing. The following day, with no provisions left, Seghers collapsed in exhaustion. Finally the two missionaries followed the example of the Kyuquots, gathering mussels and berries to eat. They staggered on, eventually reaching Ucluelet, where they sought refuge at Captain Francis’s trading post. He provided them with food and also new shoes and pants because “our clothes had been reduced to rags in our attempt to travel through the brushwood.” Brabant reported that two full weeks passed before they regained their strength.

When they recovered, they arranged canoe transport up the Alberni Canal, then travelled on foot and by canoe to Qualicum, on the east side of Vancouver Island; from there by canoe to Nanaimo, and finally by steamer back to Victoria. Through all this, their zeal never faltered. According to Bishop Seghers’s calculations, over the course of their two west coast visits in 1874 they had baptized 960 people, most of them children. This statistic grew to 1,000 in later reports. Given that the population of Indigenous people on the coast at the time probably totalled no more than 5,000, this figure could well be exaggerated, but whatever the number, the two missionaries felt they had accomplished a great deal.

Several months passed before Father Brabant received his marching orders, but finally, in February 1875, Bishop Seghers directed him to go to Hesquiaht to “take charge of the West Coast Indians.” Formal instructions for the mission at Hesquiaht, written in Latin and dated March 22, 1875, stress that the missionary should “encourage labour and growth of industry, and…inspire the love of agriculture,” as well as devoting himself to the “salvation and spiritual progress of the Indians.” In selecting Brabant to become the first missionary on the west coast, Bishop Seghers had found the perfect man for the job. A man of uncompromising commitment and great physical endurance, Brabant never hesitated to exert himself to any extreme in his work as missionary to the First Nations of the west coast.

On May 6, 1875, just over a year after his first visit to the area, Brabant set sail for his new home on board the sloop Thornton. With him travelled Father Rondeault, a Belgian priest stationed at Quamichan, and a carpenter, Noel Leclaire, who came along to help construct the first mission buildings. They were also accompanied by “three small calves, one bull and two heifers,” destined to become the pioneer cattle of Hesquiaht Peninsula. Father Brabant’s Newfoundland dog completed the crew. They set to work at once, as Brabant explained, “to put up a church of 60 X 26 feet [18 X 7 metres] and a small residence for the priest. Everything was to be done as cheaply as possible.”

Some building materials used in the construction came from the shipwrecked American barque Edwin. In December 1874, loaded with lumber at Puget Sound and bound for Australia, the Edwin took on water after the cargo shifted. Despite the best efforts of Captain Hughes, the ship’s master, the barque ran aground near the entrance to Hesquiaht Harbour, prompting a heroic rescue effort on the part of Chief Matlahaw and his men. They managed to save most of the crew, but the captain’s two little boys and the Chinese cook drowned, and the captain’s wife died when the ship broke up. The Canadian government later awarded Chief Matlahaw and his people a silver medal. “On the one side is a beautifully executed profile of the Queen, and on the other the following inscription: ‘To Ma-ha-clow, Chief of the Hesquiakis, for bravery and subsequent kindness in rescuing the Captain and crew…December 1874,’” reported the British Colonist. The United States government also acknowledged the rescue by presenting a cash reward to the Hesquiahts.

On July 5, 1875, the first Mass took place in the newly constructed, newly dedicated, St. Antonine Church at Hesquiaht. Brabant reported: “All the Hesquiahts were present; also, the Chief and a crowd of Muchalat Indians.” The following morning, Rondeault and Leclaire left for Victoria, and the priest found himself alone and, in his own words, “in charge of all the Indians from Pachena to Cape Cook.” Within a month, Brabant set out on a missionary trip to Nootka and Kyuquot, setting a precedent he would follow for all his years on the coast. Although based at Hesquiaht, he continually travelled along the coast from village to village, seemingly indifferent to personal discomfort and danger. His constant travels proved essential in establishing his authority, inspiring respect for his personal endurance, and enabling him to learn about the local hierarchies, family connections, jealousies, and rivalries on the coast. He established local alliances, befriended important people, and as time passed he imprinted himself on the local people as the first European in the area who had come to stay, who would not be deterred, and who, on occasion, spoke up strongly on their behalf to figures of authority.

By late September 1875, a terrible shadow hung over Hesquiaht. Smallpox broke out, having spread from Nootka Sound. Many people died, and soon dead bodies lay untended; no one dared approach them. Brabant took charge, administering vaccinations, issuing instructions for the dead to be buried and for the sick to remain isolated, fully realizing the gravity of the situation, and trying to calm the panicky fear that dominated the village. The journal he kept at the time, parts of which appeared in the Colonist, tells a sobering story.

Brabant’s memoirs describe one occasion during this crisis when everyone wanted medicine and, having none to give them, he “boiled water, broke some biscuits in it, sweetened the whole with sugar, and insisted that this would be the very best preservative in the world against smallpox.” He vividly recalled attending one of the chief’s daughters as she died, “a courageous woman [who] did not give up till she was quite blind and her head as black and thick as a large iron pot…The sight of the corpse was simply horrible.” As the smallpox outbreak progressed, he “passed most of [his] time in vaccinating the Indians and in trying to cheer them up.”

According to the Colonist, Chief Matlahaw’s family suffered great losses in this outbreak of smallpox. Two of his children died, as well as his sister and his wife. Matlahaw himself fell victim to the smallpox; he came to stay in the priest’s house and received two vaccinations, but according to Brabant the vaccine had no effect, and the chief “became morose and avoided the company of his friends.” What next occurred nearly cost Brabant his life. On October 27, just as Brabant began hoping that the worst was over, Chief Matlahaw asked to borrow his gun to shoot some jays. When Brabant asked for the gun later in the day, Matlahaw shot Brabant, first in the hand and then in the back. Chaos erupted in the village, and Matlahaw fled—perhaps crazed by the smallpox he carried, perhaps bitterly angry with Brabant and holding him responsible for the plague that had struck the village, but certainly aware that shooting this powerful outsider would have serious consequences.

Convinced he would die, and in great pain, Brabant could do nothing but wait helplessly while being anxiously tended at his house by several Hesquiahts. Incapable of moving, he instructed his supporters to place cold-water compresses on his hand. The Hesquiahts sent word to Refuge Cove and to Clayoquot, seeking assistance; none arrived. The Clayoquot storekeeper, Fred Thornberg, always suspicious of the Indigenous people and fearing infection and reprisals, responded to the request for help by sending several yards of white cotton back to Hesquiaht, to wrap Brabant’s corpse. In later years, Thornberg and Brabant laughed at this memory; Brabant eventually used the fabric for dishcloths. At the time, with his wounds feverish and inflamed, this lack of help must have been a terrible blow. Eventually a deputation from Hesquiaht reached Victoria by canoe to report the attack to the bishop and to the police. Brabant sent with them “a paper on which I had written a few words every morning.”

“My Lord,” he wrote to the bishop, “I am dying, I am shot in the right hand and back by Matlahow the Hesquiot chief…Adieu! Pray for me.” He added: “The Indians are very kind. The whole tribe is crying day and night. At least three are taking care of me. Do not blame them. Praise for their kindness, and may another priest be soon here to take my place is the wish of your lordship’s dying servant.” Brabant also sent to the bishop his daily journal of what had happened during the outbreak of smallpox leading up to his attack. On November 7, 1875, the Colonist printed some of this material.

Two days later, the naval gunship HMS Rocket came to the rescue at Hesquiaht, bringing two doctors, Bishop Seghers, and the chief of police. Within two more days, Father Brabant had been transported to Victoria and was receiving medical care. Fears for his life abated, but doctors told him his hand would have to be amputated, an operation he refused to consider, against all advice. Eventually the hand recovered, but he had to remain in Victoria for five months. Determined he would return to Hesquiaht, in late March Brabant boarded a sealing schooner heading up the coast. Stopping overnight at Ahousaht he wrote, “The Ahousath chief seemed happy to see me, and his Indians were immediately summoned to his house. The Ahousaths astonished me by their good conduct. I baptised all their newly-born children, 8 in number. Altogether I had 25 baptisms on my way to Hesquiat; no objections were made anywhere. Upon landing, every man of the tribe was on the beach to welcome me home.” Arriving at Hesquiaht on April 5, Brabant found his house as he had left it; the floor was still covered with dried blood and littered with dressings. The Hesquiahts welcomed him back and gave a feast in his honour, with “dancing and gesticulations, and many other extravagant things.”

Brabant never considered not returning to Hesquiaht following the attempt on his life. If anything, this drama heightened his determination to carry on, and to outface any future attempts to scare him off. Within months of his return, while on a visit to one of the dwellings of Chief Maquinna of the Mowachaht tribe, he discovered a plot on the part of Maquinna to kill him. He narrowly escaped with his Hesquiaht companions in the early morning. Later, discovering that Maquinna’s animosity arose from false accusations against him and his companions, he simply shrugged it off. “I was told that such a practice is very common with savages of this coast,” his memoirs state. When rumours circulated in the villages on the coast that Father Brabant planned to kill all the Hesquiahts, he remained unperturbed, convinced he was among friends who would stand by him and never turn on him en masse. Later, in a letter to his bishop, he wrote: “The Indians are so very kind and obliging that I am quite happy in their midst; there may be another traitor in the crowd, but traitors you will find everywhere among the whites as well as among the natives…I came here with my full consent, and…there is no more danger in Hesquiath than of an evening in the streets of Victoria.”

“The Indians feared Father Brabant and called him the ‘Big Chief,’” wrote Charles Morin in his unpublished memoirs, recalling a time shortly after the attempt on Brabant’s life. Morin, a carpenter from Quebec, worked alongside Brabant constructing a church in Barkley Sound. Seeing Father Brabant in action among the people he called “his” Indians, Morin noted that, following Brabant’s return to Hesquiaht in 1876, “the...Indians on seeing him back alive thought he could not be an ordinary man so it gave him greater power among this tribe.” One of many contemporary observers who commented on Brabant’s physical appearance, Morin observed that “he was a man of massive build, six feet tall and weighing around 200 pounds. He had a very young and handsome face, very interesting to talk to and with health to match. He could survive on dry fish and biscuits, could sleep outdoors and could pass days out in the open, rain or shine, as nothing seemed to bother him.”

In the summer of 1876, two new enthusiasts joined the ranks of the Roman Catholic missionaries on Vancouver Island, swelling the number of clergy in the diocese to nine. Fathers Jean Lemmens and Joseph Nicolaye had been nearly two months in transit to Victoria from their native Belgium. They spent time en route in New York and then Philadelphia, where they spent four days marvelling at the Centennial Exposition there, the first World’s Fair. This massive show featured industrial and ethnographic displays from around the world, including an eighteen-metre-long canoe from Nootka. Then on to San Francisco and Portland, and finally Victoria, described by Father Nicolaye as “already a city of great prestige, with a great future in store.” Within weeks the two young men set forth to their respective mission fields: Father Lemmens to become the first incumbent in Nanaimo, until then visited once a month by a priest; while Father Nicolaye, accompanied by Bishop Seghers, boarded the schooner Alert, bound for Hesquiaht. There he would become a novice missionary under Father Brabant’s guidance. Describing his first voyage up the coast, Father Nicolaye mentions rivalling the bishop to see who would be the more seasick, and also, incongruously, the fun they had with a “cute little black bear on board.” “He was not very vicious,” Nicolaye wrote. “…He liked to play, as puppies sometimes do…yet it was deemed necessary to chain him up.”

Shortly after arriving at Hesquiaht, Father Nicolaye came upon the remains of Chief Matlahaw at the foot of a hollow tree not far from the church. Little remained but his bones, his clothing, and Brabant’s gun. “Having shot Father Brabant…he fled into the woods and was never seen or heard of till we found his remains,” wrote Nicolaye, carrying on to speculate: “He must have felt unsafe among his own people.” The Hesquiahts knew about the body; Brabant learned they had discovered it shortly after his departure for Victoria aboard the Rocket. In a letter to Bishop Seghers about Chief Matlahaw’s body, Father Brabant wrote: “[The Indians] look upon the spot where his remains rest as a cursed spot. His child is taken care of by his wife’s mother and father, and they bring him almost every day to my house; I told them to take care of the child as if he were their own.”

Father Nicolaye settled in at Hesquiaht, learning from Brabant the evolving plan for the west coast mission. Soon it would be split in two sections, with Brabant in charge of the northern section and Nicolaye based farther south, in Barkley Sound. First he had to learn the language. The two priests diligently studied the Chinook trading jargon, but Brabant took his studies much further, focusing in detail on the local Hesquiaht language. Led by the example of Charles Seghers, Brabant already was proving himself a gifted linguist, and in later years he spent considerable time assembling a meticulously detailed dictionary of the Hesquiaht language, totalling some 134 pages, a document that remains to this day in the archives of the Roman Catholic diocese in Victoria.

In learning the language, the priests at first concentrated on religious concepts and vocabulary, not entirely trusting the local interpreters to convey their meaning correctly. Misunderstandings inevitably arose. According to Nicolaye, when Brabant told his interpreter to explain that everyone should bless him or herself with the holy water at the church door, the translator announced, “In future there will be at the church door a tub of water, soap and towel, and everyone is to have a good wash before entering the church.” By early July 1876, Brabant reported with satisfaction that “[the Hesquiahts] all know the first lesson of Catechism in their language…I expect to have High Mass in about two weeks; the Indians being able to sing to perfection the Kyrie, Credo Sanctus, and Agnus Dei.” Before long, Brabant was delivering his sermons in the Hesquiaht language.

From the outset, Brabant asserted his authority over secular life in the village. He insisted that “Christian” clothing be worn, initially decreeing that men, women, and children should at least wear a shirt in church, and later that men should wear pants to cover their “naked lower limbs.” If they did not comply with this dress code, people could not enter his house or the church. He appointed local “policemen” to be his representatives and spoke out forcefully against tribal practices. He realized, especially in the early years, he had very little impact, despite the apparent “conversions” to Christianity. “They laugh at the doctrine I teach,” he admitted once. Never deterred by negative reactions, he thundered on against adultery, “pagan” dances, medicine men, and traditional ceremonies.

During the late 1870s, Fathers Brabant and Nicolaye remained the only two Catholic priests on the west coast. Their isolation at Hesquiaht proved trying at times. “We have not seen a white man since October,” Brabant wrote in March 1877, “and we have not received any mail for several months. Our provisions are nearly all gone…and our Indians are as bad and as much attached to their pagan ideas as before we commenced our work here.” By Christmas of 1877, the second church on the coast, at Numukamis in Barkley Sound, neared completion. The first Mass at this mission took place on Christmas Day in the small house built for Father Nicolaye. Some 150 people of the local Huu-ay-aht tribe squeezed into the small space, perching on blocks of wood. The carpenter, Charles Morin, described the event with some amazement in his diary: “Some…were leaning on their elbows, other sitting cross-legged, some had climbed up near the ceiling and were looking down, others had their back ends up and heads on the ground.” After the Mass, the chief spoke at length, gesticulating toward Father Brabant: “I say no more wars against other tribes, no more disputes in camp, no more women beating and no more women stealing. We will keep our own women and I will support this priest in what he says…I want to believe the story he has just told us of the Great God…He will listen to us and help us.”

Following this encouraging start, Father Nicolaye took up permanent residence in Barkley Sound and almost immediately found himself entirely on his own at the newly constructed mission. Everyone in the village left to go fishing and sealing; he rarely saw another soul for four months. Nicolaye remained there for two years, serving the fluctuating population as best he could before going up to Kyuquot in 1880 to establish another mission and church. He remained at Kyuquot for ten years.

At Hesquiaht, on October 9, 1882, another ship came to grief on Perez Rocks, near where the John Bright met its fate. Under the command of Captain Edward Harlow, with a crew of eighteen, his wife, Abbie, and their two children aboard, the 924-ton American barque Malleville was dashed on the rocks. Local Hesquiahts soon found evidence of the wreck, and one of the bodies, at their fishing camp at Home-is. They alerted Father Brabant, who took a crew of men and went to investigate. They found many items washed ashore, including a trunk full of clothing, the letter-blocks and toys of the little Harlow boys, and the body of their pet pig. They also located the body of Mrs. Harlow. Brabant explained in his diary how “the Indian who discovered Mrs. Harlow’s body and brought it ashore, had taken from her hand two diamond and gold rings—wedding and engagement rings; also two diamond earrings, a gold pin and a piece of gold chain…This man afterwards gave me these articles and asked me to take them in charge.” Seven other bodies were also recovered. Brabant noted the “noble and heroic” efforts of the Hesquiahts to recover the bodies, “up to their necks in the surf dragging the bodies to shore.”

Word reached naval authorities at Esquimalt, and on November 22, HMS Kingfisher arrived at Hesquiaht. Captain Thornton conducted his investigation and left two days later. Entrusted to him was a parcel containing Mrs. Harlow’s recovered jewellery, together with her Bible and sealskin coat, to be sent to her parents in Maine. Later, the United States government awarded the Hesquiaht chief a gold medal as “a souvenir of the kindness and humane conduct of the tribe,” as well as $200 to be distributed among his men in recognition of their bravery.

In 1883, Father Jean Lemmens joined the ranks of the west coast missionaries, delighted to leave his parish at Nanaimo to go to “this part of the island [which] was the most desired part for the missionaries.” He initially joined Father Nicolaye at Kyuquot, while Nicolaye started to do mission work at Ehattisat and Nuchatlat. Following the example of Father Brabant, these priests asserted temporal as well as religious authority wherever they found themselves. They organized local “policemen” to be their supporters in the villages, they meted out punishments for perceived wrongdoings, in some locations they even established “jails” where they could confine people who had, in their view, done wrong. In his diary of 1884, Father Lemmens wrote: “Mar 3: Put the pock-marked Kyuquot man in irons, and his wife in jail; cause ‘katpathl’ [they had a fight].” The following day, March 4: “Put a woman doctor in jail for doctoring her old mother. Gave the old woman baptism and Extreme Unction. Had her corpse taken into jail till next morning.”

Later, when Father Lemmens became established as the missionary at Opitsaht, he again operated a jail. A memoir of his life, assembled by family members following his death, states that when he was at Opitsat, “even for small offences, jail was one solution to keep the peace. One Indian set up a party during Mass, only after payment of three blankets was he released from jail.” The offences most often noted by the priests included adultery, bigamy, fighting, drunkenness, holding to old beliefs, and “witch-doctoring”—as well as missing Mass.

Following his time in Kyuquot, and before going to his next mission at Alberni, Father Lemmens travelled to the Council of Baltimore, a large gathering of American clerics, and from there to Europe. His diary entry about this long voyage, foreseen while still at Kyuquot, states: “Went to Alberni, via Baltimore, Antwerp, Shimmert, [Schimmert, in Holland] Victoria and Dodger’s Cove.” At Alberni he built a church and tried to settle in to his new mission, but he badly wanted to be on the outer coast. On a return visit to Kyuquot, he met with Bishop Seghers—now archbishop of Oregon—and Father Brabant, and they set in motion a plan to establish another permanent mission, this one at Ahousaht. Brabant had already built a small church there in 1881, but they now decided a priest should take up residence in the village. Fred Thornberg, the trader at Clayoquot, built a house at Ahousaht for Lemmens in 1885; later, Thornberg occupied this house himself during his years as a trader at the village.

“There were days,” Father Lemmens’s family memoir states, “that he was doing nothing else than provide medical advice.” Like all the priests, Lemmens became, de facto, the resident medic wherever he found himself on the west coast. With disease rampant among Indigenous people, this medical role became central in priests’ lives, establishing them as authority figures in the lives of people on the coast. In many instances, government agencies provided mission priests with medicines to dispense. Another means of asserting authority involved schools: all of the priests, from time to time, attempted to open small day schools in the villages, teaching reading and writing to the few children who could be convinced, bribed, or coerced to attend.

Father Lemmens did not remain long at Ahousaht, but he described the place vividly in letters home. The Ahousahts, he reported to his family, “had tendencies to dispute during Mass, and after Mass they argue about the homily with all the noise they could make.” He tried very hard to stop that, but they said “You take us as we are, otherwise you will have to say Mass in an empty church!” By 1887, Lemmens divided his time between Ahousaht and Opitsaht, likely spending more time at Opitsaht, where he had assisted in constructing a new church and priest’s house, and where he attempted to run a school. Opitsaht generally proved more appealing to the missionaries than Ahousaht, being a busier place, less isolated, and within sight of the trading post at Clayoquot. Like Brabant, Lemmens proved to be an outstanding linguist, and like Brabant he spent considerable time and effort compiling a dictionary of the local language.

In July 1886, Archbishop Charles Seghers was murdered on a mission trip to Alaska. With considerable reluctance, Father Lemmens agreed to be nominated as the next bishop of Victoria, and found himself bishop-elect. He remained as long as possible at Opitsaht, delaying his consecration as bishop until August 5, 1888. He served in his new office for nearly ten years, frequently visiting the west coast.

With his old friend Charles Seghers dead, and with so many of the Indigenous people on the coast dying all around him, Father Brabant came near despair. Disease spread rampantly along the coast as the local people moved to canneries, to potlatches in other villages, to take up seasonal employment on the hop farms of Puget Sound, or simply to and from their summer encampments. Measles and whooping cough took their deadly toll, smallpox continued to be a major concern, and the terrible scourge of consumption became increasingly prevalent. “Before long,” wrote Brabant at the end of 1886, “I counted over forty children of Hesquiat alone who had become victims of the disease. With my bishop murdered and my young people dying around me, I closed this year with many, many sad feelings.”

By 1888, four Roman Catholic churches could be found on the west coast, at Hesquiaht, Kyuquot, Ahousaht, and in Barkley Sound. At the end of that year, Father Brabant occupied himself building the fifth, at Yuquot in Nootka Sound. He attempted to run this mission himself, from Hesquiaht, although in later years Yuquot would be served by various resident priests. The missions at Ahousaht and in Barkley Sound never thrived. Brabant bitterly regretted the failure of the one at Ahousaht; he blamed Father John Van Nevel, who succeeded Father Lemmens as missionary both at Opitsaht and Ahousaht. Van Nevel favoured Opitsaht, leaving Ahousaht “abandoned and neglected,” according to Brabant.

Given the expansion of the fur sealing trade from the 1870s onward, and the central role played in that trade by Indigenous hunters from the west coast, the early Catholic missionaries found themselves involved on the sidelines of the seal hunt. In 1876 Brabant observed “a dozen or more sealing schooners” calling at Hesquiaht; he came to know all the schooners and their captains, sometimes travelling up and down the coast with them. Brabant robustly supported the fur seal trade, occasionally intervening to make sure that sealing captains did not cheat “his Indians,” and that they received appropriate pay and treatment. He encouraged local hunters to hire out on the sealing schooners, not least because the money they brought back would enable people in the villages to acquire what he termed “the accoutrements of Christian civilization.” He wholeheartedly approved of the influx of trade goods and the growth of a cash economy among First Nations people: on his very first trip to Kyuquot in 1874, Brabant noted with pleasure the “women in white calico robes and the men with pants and coats.” Seeing how the villagers adopted European clothing and household goods, he encouraged the construction of small individual houses to replace the traditional big houses, rejoicing when curtains appeared on windows, when the villagers began to use furniture rather than sitting on the floor, when Singer sewing machines and musical instruments became popular consumer items on the coast. All of this, for Brabant, indicated rejection of traditional “pagan” ways and acceptance of Christian values. Subsequent missionaries on the coast concurred, frequently using goods like hair ribbons, grapes, oranges, and candy to buy goodwill from the people they were trying to convert. Traders on the coast all benefited from this unspoken collusion, as the missionaries tacitly and sometimes overtly promoted sales of various goods.

Nonetheless, during his many long years on the coast, Father Brabant kept a keen eye on the actions of all traders and storekeepers, quick to comment on any hint of dishonest or immoral behaviour. He would thunder condemnation if any trader sold liquor to Indigenous people, and he was quick to report any such infraction. Outraged at the evils brought on by alcohol, by disease, by the “vicious” behaviour of some white men, particularly toward local women, Brabant well knew the consequences suffered by the Indigenous population. Writing for the American College Bulletin in July 1893, he commented, “On our first visit to this coast, nineteen years ago, we roughly estimated the Indian population in my mission at 4,500 souls. Now I doubt whether there are more than 3,000.”

In October 1891, Brabant noted a dire new development on the coast: “I understand that a young man representing the Presbyterian Church of Canada has taken up his residence at Alberni.” This young man, the Reverend Melvin Swartout, later moved to Ucluelet, where the first west coast Presbyterian mission had been established in 1890. The Protestants had arrived; more soon followed. Brabant tracked their progress closely. In 1895 he wrote contemptuously: “A monthly steamer now visits the coast…When a man’s life was in danger and when the only means of travelling was an Indian canoe, when the mails reached us only once or twice a year…we were welcome to do alone the work of converting the natives. Now with the…absence of danger, the ministers come in sight.” By 1896, these encroaching “heretics,” as Brabant called all Protestants, had come to stay in the territory Brabant considered his personal fiefdom, audaciously positioning themselves smack in the middle of Clayoquot Sound. “A young man representing the Presbyterian Church is now stationed in Ahousaht,” Brabant wrote angrily. “He is a school teacher by profession, but he holds divine service on Sunday…the poor little children so anxious to learn to read and write will be perverted without noticing it.” This first Protestant missionary at Ahousaht, John Russell, quickly established a small day school there, funded by the Women’s Missionary Society.

Over subsequent years, Brabant raged continually, and at length, about the carryings-on of Protestants. He could not express himself too strongly about what he judged to be Protestant perversions of the faith, their corrupt tactics, and the stealing of souls of the people he considered “my Indians.” Yet in a moment of sober reflection, writing to a fellow priest in Belgium in 1903, Brabant did admit that Protestants were not altogether evil, and also, most unusually, he admitted that his fellow Catholics had not been without fault in their early mission work on the west coast. “[The Protestants] came with tons of clothing and dress goods for old people and children and set to work with a zeal, an energy, and a spirit of self-sacrifice worthy of a better cause…[They] are well-behaved…hard-working men and women, putting up with all kinds of hardships and privations, and, by their zeal and perseverance, they put to shame some of our priests, who abandoned their Indian charges to do work in white congregations…The Protestant preachers have taken possession of quite an extent of our Coast. The trouble is—our Bishop has no priests to occupy the field…Several strangers, having learned of the need of priests, offered themselves. They were well recommended, came here, stayed a time, got drunk or did worse, and went away to parts unknown, leaving behind them scandal and damage to the cause of religion.”

Brabant never again alluded to such problems among the early Catholic priests on the coast. Whatever the misdemeanours in question, he named no names, gave no specifics, and the subject never recurred. From the late 1880s through the 1890s, a number of different priests came and went on the west coast, Father Van Nevel among them; also Father Eussen and Father Verbeke, who briefly served in Barkley Sound and in Opitsaht. Verbeke, who had never been in a canoe before he took his first trip across Barkley Sound, astonished his Indigenous paddlers by insisting on taking his caged canary with him. Other priests of the period included Father Meuleman at Kyuquot Sound in the 1890s, Father Heynen at Opitsaht, and Father Sobry, who stayed over two decades on the coast, first at Kyuquot and latterly at Yuquot.

In Father Brabant’s opinion, this scattershot of priests was inadequate, given the Protestant invasion. He demanded more Catholic action. By the mid-1890s, he had decided the west coast must have a residential Catholic school for Indigenous children, drawing them from villages up and down the coast. With his customary energy and determination, he began lobbying the authorities with this in mind.