Chapter 16: Boat Days

No such vessel had ever been built in British Columbia. Anticipation of her imminent arrival on the west coast route gripped everyone’s imagination. The largest ship ever built in the province, launched on Christmas Eve 1912 at Yarrow’s Shipyard in Esquimalt, the SS Princess Maquinna would surely transform travel along the coast. Proud descriptions fill the annals of the CPR, with detailed litanies of her technical merits: “3 cylinder Triple Expansion. Single Screw. 1500 Horse Power, 2 Scotch Marine Single Ended boilers. Speed in knots 12.5. Working pressure 180 lbs. [81.5 kilograms] 6 Furnaces, Fuel Capacity 1,705 barrels…Overall length 244΄ [74.3 metres] Length between perpendiculars 232΄ [70.7 metres] Breadth 38΄ [11.5 metres] Gross tonnage 1,777, 50 rooms, 100 beds or berths, 70 crew members.” Translated, this meant a ship bigger, better, stronger, faster, and far more reliable than any the coast had seen before.

The Daily Colonist revelled in describing the interior, “all panelled in mahogany, with cornices and pilaster finishing,” and the bevy of “furnishers, decorators and others” feverishly preparing the ship for her maiden voyage up the west coast of Vancouver Island in July 1913. “A fine boat,” concluded the laconic Father Charles Moser, who travelled on this first voyage. His confrere, Father Joseph Schindler, commented a few months later: “The Tees looks like a wash tub along side of [Maquinna] and small.” Everyone compared the splendid new ship to her unfortunate predecessor, SS Tees.

Even though she had been built specifically for the west coast route, with her double hull and ease of manoeuvring in narrow inlets, the Maquinna did not serve full time on the route until 1917. Initially, the wharves along the coast, many of them flimsy, worm-eaten structures, could not cope with her size; some needed to be doubled in length to allow her to dock, and much rebuilding had to take place to accommodate her. So during her earliest years, other routes often claimed the Maquinna, and west coasters felt cheated; they had been promised this gem of a vessel, yet most of the time they still had to make do with the much-derided old-timer Tees.

The Tees had served the west coast on and off since her inaugural trip from Victoria to Alberni in 1896. Initially praised for her elegant finish, “all done in birds’ eye maple” with the ladies’ cabin “a wonderful dark red plush,” she even garnered approval from the captain who piloted her to Victoria from her home port of Stockton-on-Tees in England. “She rides the water like a duck,” he declared fondly. No one concurred when Tees embarked on the coastal route. “That blinking old tub could roll and take a nose dive at the same time so that hardened sailors got seasick on her,” Mike Hamilton declared bitterly. She became known as the “Holy Roller” as she pitched and rolled her way through rough seas, year after year. Slow, with her best speed nine knots, and known as a “wet ship”—mostly underwater in bad weather—she measured 50.2 metres in length. During her years of service on the coast she carried untold thousands of passengers—her record load being 147—and countless cargos of whale and dogfish oil, fish meal, cans of salmon, building supplies. Still, no one grieved when this “blunt-nosed ugly duckling” finally left the west coast, giving way finally and permanently to the Princess Maquinna in 1917. Yet the Tees, along with earlier steamers serving the west coast, particularly Queen City, Willapa, and Maude, truly set the stage for the Princess Maquinna. These ships established the pattern of regular steamer traffic: for many years their arrivals were awaited with almost painful anticipation, and they served the coast long and honourably. In subsequent years, though, Princess Maquinna took all the laurels; she set a new gold standard and became perhaps more beloved than any vessel in the CPR’s Princess fleet. “If ever a ship took on body and soul and personality…loved by all who sailed in her, it was the Princess Maquinna,” wrote Dorothy Abraham. No one ever disagreed.

From 1913 to 1929, Captain Edward Gillam had charge of the Princess Maquinna. Universally liked and respected, Gillam seemed as much part of the boat as the green leather seats in the saloon or the ungainly funnel with its cracked-tone whistle. He knew the coast from Victoria up to Port Alice as well as any man alive, and he also knew most of the people who lived along it. At one time or another most people on the west coast became his passengers: their stories and dramas were paced out on the deck, recounted in the saloon, discussed in the dining room, witnessed at close quarters. Captain Gillam knew that he provided not just a link between people and places on the west coast; he provided the link, the only consistent, regular, long-standing means of travel and communication on the coast. A large, companionable man, kindly and firm, Gillam became renowned on the coast for his outstanding seamanship, his ability to navigate in thick fog through the trickiest of channels. He knew every rock and reef, every echo when he sounded the ship’s whistle, and how the echoes varied from location to location. He knew the very dogs barking in the dark nights as he approached different settlements, he knew how to manoeuvre his large ship into position on any given dock by calculating the tricks of wind, tide, and current. Originally from Newfoundland, Gillam came to Victoria in the latter days of the sealing industry, eventually joining the Canadian Pacific Navigation Company as a deckhand. Later, with the company renamed the British Columbia Coast Steamship Service, he served as an officer aboard Willapa and Queen City, and became captain on both Queen City and Tees before taking command of Princess Maquinna.

Early in his years aboard Princess Maquinna, Captain Gillam gained widespread renown for his valiant attempt to save the foundering Chilean barque Carelmapu. In November 1915, this three-masted ship came to grief off Gowlland Rocks, just up the coast from Schooner Cove at the north end of Long Beach. Driven off-course by extremely high seas and winds, with her sails shredded, the ship had been drifting helplessly for two days, ever closer to the rocky shore of Vancouver Island. Travelling southbound on the Maquinna, Captain Gillam tried his utmost to come to the rescue of the vessel, approaching as close as he dared in the towering breakers, close enough to make himself heard through a megaphone. Positioning Maquinna’s stern toward land, he dropped both anchors and ordered half-speed from the engines to maintain position. Two attempts to shoot a line to the doomed ship failed. The captain of the Carelmapu, Fernando Desolmes, lashed himself to the ship’s railings and ordered the two lifeboats to be lowered, hoping they could reach the Maquinna, knowing the chances to be slim. The first boat did not even hit the water before spilling all passengers into the heaving sea. Gillam ordered fuel to be spilled over the water to break the crests of the waves, but when the second lifeboat tried to steer toward Maquinna, a huge wave flipped it over. No one in the lifeboats survived. Meanwhile, the danger for Princess Maquinna became too extreme; her straining cable winch seemed about to heave the deck apart. “The terrific strain injured the winch,” according to Mike Hamilton’s account, “to such an extent that the anchor could not be hauled in. The first mate, Captain Kinney, was obliged to crawl forward with a hack saw and saw through the link, letting chain and anchor go.” Captain Gillam had to leave the Carelmapu to her fate. Desolmes waved a despairing farewell as Princess Maquinna headed out to sea, her fifty passengers looking back in horror as the mizzen mast of the shipwrecked vessel ripped off, tossing two of the remaining men on board into the sea. Desolmes released himself from the railing, genuflected, and dropped into the ocean. Against all odds, he made it to shore. Four others also survived. Nineteen perished.

At Long Beach, settler John Cooper buried eleven of the bodies that eventually washed up on the shore; he later wrote “nobody knows where they are but myself.” Captain Desolmes and one of the survivors, Rodrigo Dias, stayed at Long Beach with Cooper; the other three went to the hotel at Clayoquot, in care of the Tofino lifeboat crew. “All were in very bad shape,” according to Cooper. The captain’s Great Dane dog, named Nogi, somehow made it to shore, and Cooper kept him—he wore a brass collar with the name of the ship on it. Two years later someone shot Nogi and stole his collar. Cooper, who lived at Long Beach for eleven years before moving into Tofino, had bad luck with his pets. He had “quite a herd of cattle, a team of Arabian horses, pigs, chickens, ducks and a tame deer known as ‘Jackie of Long Beach.’” Jackie also was shot by a hunter, and the sea lion Cooper befriended, “a tame one, quite a pet, that used to come up to the house,” was happily snoozing on the sand near Cooper’s home when a hostile logger attacked and killed it.

The Maquinna era on Vancouver Island’s west coast has acquired the glow of legend over the years. From the heroic attempt to rescue the Carelmapu to simple stories of gathering around the ship’s warm funnel, nothing in the collective consciousness of west coast residents can match the shining memories of the Maquinna. Every ten days for nearly four decades this faithful ship ran up and down the coast of the Island, leaving Victoria at 11 p.m. on the 1st, 11th, and 21st of every month, arriving Tofino northbound on the 3rd, 13th, and 23rd. On those northbound trips, when Princess Maquinna steamed into sight in Tofino Harbour, the town and the whole harbour came alive. This was “Boat Day”; the very words evoked an inner tremor of anticipation. “People came from all the outlying parts,” Dorothy Abraham wrote, “in launches and craft of all kinds: also the Indians, gay with colour, in their canoes.” “It was during ‘boat-day’ that one could expect every one, queer, odd and otherwise to make their appearance,” wrote Mike Hamilton, “to get their groceries, mail and…mysterious crates, jars and packages…They would converge upon [the wharf] in canoes, skiffs and rowboats, from all directions.”

Maquinna’s strangulated whistle sounded as she passed by Lennard Island and entered Tofino Harbour. Everyone in the village knew that sound, and hearing the whistle, children rushed down to the government wharf, along with anyone meeting the ship to collect goods or visitors or mail—and pretty much everyone else in town came too, just for the fun of it. “All of us kids wanted to catch the rat line,” Ken Gibson recalled. “We’d hear that whistle out in the harbour and just run like heck down to the dock to be there when the Maquinna came in.” Catching the monkey’s paw, that heavy ball of spliced rope connected to the thin rat line, in turn connected to the heavier line, the hawser, “meant we were bringing the boat in!” Local children would stampede onto the ship and run straight for the commissary with their nickels and dimes to buy Cracker Jack popcorn, Superman and Flash Gordon comics, chocolate bars. Even during the days of World War II rationing, the Maquinna still sold chocolate and candy, adding to her aura of magic for local children.

On board, the “ear-splitting and nerve-shattering” noise of her steam whistle, heard up close, would send Mike Hamilton’s young children screaming to their mother, hands clapped to their ears. “That whistle was History all in itself,” Mike Hamilton wrote in his unpublished memoirs, describing how it “would begin with a sort of squeal of a one-or-two second duration before the shattering blast commenced which…gave you time to steel yourself against the shock.” Joan (Malon) Nicholson has happier memories of that sound; to her great delight, as a young child coming home to Tofino, she had the privilege of going up onto the bridge and, on a signal from the captain, pulling the whistle cord. “I think I was the only kid in Tofino who did that.”

“The sound of the Princess Maquinna’s steam whistle meant more…than Santa Claus himself,” wrote Alder Bloom, and the bustle at the dock, as recalled by Ronald MacLeod, provided non-stop entertainment with “freight and mail unloading; salesmen coming off with their large sample cases and rushing to cover the two general stores in the limited time before the ship sailed on; a host of tourists in summer, travellers to upcoast communities enjoying a brief visit on the dock with friends...Up and down the wharf would trundle handcarts carrying newly arrived freight to the two stores. A hive of activity!” People waited anxiously, wondering if their mail orders had arrived or their liquor orders, mysteriously wrapped in brown paper, having been paid for and requested ten days earlier by filling out a special form.

As for the sheer fun of seeing strangers—nothing could match that. “What oddball tourists in their strange getups will we see today?” Ronald MacLeod always wondered. In the summertime, those tourists would stroll along the dock, where they met Indigenous people selling their crafts: baskets, mats, and covered bottles the most popular items. The visitors would roam around the village, pause for snapshots, and drift along Grice Road on the waterfront to see all the activity at Towler and Mitchell’s store.

Lorraine (Arnet) Murdoch particularly liked Towler and Mitchell’s store on Boat Day. Her parents did most of their trade here, running a tab, like everyone else, to be paid off after fishing season—she never saw them pay cash. She was fascinated by the carcasses and sides of meat being unloaded and carried along the dock. People would line up and wait for their fresh meat while Jack Mitchell did the cutting—preparing the roast or stewing beef or the special cuts he would put aside for special customers. Dr. Robertson and his wife, Marguerite, often found that Mitchell had put aside a choice cut for them, although the real highlight of Boat Day for Marguerite depended on the ship’s stewards. Because Dr. Robertson had worked on the Alaska steamship run as a young man, he knew many of the crew, and they often presented Marguerite with a treat of fresh fruit from the ship’s stores: oranges, grapes, or, even more wonderful, a banana.

In their local shopping, the doctor and his wife took care to trade at both stores, showing no favouritism. Sid Elkington’s store, at the head of the government wharf, also buzzed with excitement on Boat Day. Indigenous customers favoured this store, possibly because Sid had spent many years trading in northern British Columbia, he spoke the Chinook trading jargon, and he had worked with many Tla-o-qui-aht at the cannery. Operated by Elkington and his wife, Kit, from 1930 onward, Elkington’s store, like Towler and Mitchell’s, never really closed; the storekeepers could be called out of bed at any hour by demanding customers. In his memoirs, Sid Elkington even recalled a customer hammering on the store door on Christmas Day.

The length of time the Princess Maquinna spent at the dock on Boat Days varied. It could be less than twenty minutes on days with light freight; on August 18, 1918, the precise CPR inspector, Mr. H. Brodie, noted that the Maquinna arrived at Tofino 11:16 a.m. and left at 11:34. A record copied from the Maquinna’s logbook on May 26, 1925, indicates the ship arrived at 2:29 and departed at 2:55. On other occasions, when a lot of freight had to be unloaded, or if the ship had time to spare, she could spend several hours at the dock. Little boys would watch the unloading with spellbound fascination, especially if something heavy or unwieldy—a large engine, an unhappy cow, a load of furniture, a large order of hay—had to be winched up in a sling and swung onto the dock. Ronald MacLeod recalled the rare excitement of a day in April 1931 when a Ford Model A truck arrived for Borden Grant. According to the Colonist, on that day the Princess Maquinna outdid herself, for she offloaded not only the truck but also another vehicle “over her side with derrick and sling [depositing them] on the wharf as easily as a few cases of salmon. One was a passenger car and the other a two-ton truck.” Local traffic was picking up; several cars now jolted their way through town from time to time. Mike Hamilton had brought the very first car, a 1916 Model T Ford, to Tofino several years earlier, thrilling the children, many of whom had never seen a car, by giving them rides. This car did not survive long on the so-called road in town. “In a very short time,” wrote Dorothy Abraham, “it was lying on the side of the road a total wreck.”

No one in Tofino ever received an unusual delivery off the boat without everyone knowing. In 1924 the newlywed Mabel Hamilton attracted more comment than she wished when her bedroom furniture arrived; the two single beds surprised everyone. Similarly, Winifred Guppy’s shopping habits, according to her son Anthony, caused “some people to think we were better off than we actually were…and we were resented for our perceived affluence,” in part because his mother bought in bulk, mail-ordering goods from Woodward’s in Vancouver rather than shopping locally: “fifty-pound [22.6 kilogram] sacks of flour and sugar, fourteen-pound [6.3 kilogram] boxes of butter, five-pound [2.2 kilogram] pails of shortening, large tins of Rogers’ Syrup, a case of two dozen cans of Pacific milk, and so on. It was much cheaper to buy our groceries in bulk.” Clothing, too, arrived by mail order; sometimes mothers hastily bundled their children into new clothes right there at the dock, checking to see if they fit. If not, they could immediately be returned.

Dorothy Abraham and her husband lived about 1.5 kilometres from the dock, and they usually met the Princess Maquinna with their old wheelbarrow, which they bumped along the road, often in torrential rain, coming to and from the boat to fetch their supplies. “It was quite a chore, to wheel a barrow over such a road as we had. Not a road at all...stumps, holes, mud and rocks...we got to know every inch of it, and every hole and stump...we would have to wait for the mail to be sorted...and many a time we trudged home with the old barrow at midnight or in the early hours of the morning...My job was to hold the lantern and pick the way.”

Waiting for the mail to be sorted and the parcels handed around meant many people crammed into the small post office attached to Towler and Mitchell’s, especially around Christmastime. Francis Garrard retired as postmaster in 1924, followed for brief periods by Mabel Hamilton and two other short-term postmasters until 1928, when Fred Towler took on the job. He held the position for eighteen years, assisted by Wilfred Armitage, and the good-natured mayhem at Christmas always kept them both busy. “I occasionally added to the problem as a paid helper,” Ronald MacLeod recalled, although his ten cents hardly seemed proper pay. “I emptied the mail sacks on the floor, stacked the empties in a corner and tried to keep the floor cleared of waste paper. Outside the Post Office there would be a long line of people, fretting and anxious to know whether their Christmas mail orders had arrived.”

By the time the mail was sorted, the Maquinna had departed. Five minutes before leaving, the ship’s whistle screeched, warning visitors on board to disembark. The steam winches clanged and clattered, seagulls took off in whirling cacophony from the dock and nearby boats, little children would cry at all the noise, and after a flurry of farewells the excitement faded. The boat pulled away. Silence resumed. “Skiffs, canoes and rowboats fanned out in their homeward direction,” Mike Hamilton wrote. “A period of semi-desolation would descend upon the scene until the next steamer arrived, and so it went on year in and year out.” The freight manifest of the ship, posted inside the large freight shed at the dock, revealed exactly what the ship had carried and enabled anyone who had not collected their freight to check if it had arrived. Anyone so inclined could also see who had received a liquor order and plan social visits accordingly. Mike Hamilton remembered two locals in particular who always took nocturnal rambles down to the freight shed after the boat had left: one unnamed gentleman, known to be constantly thirsty, and Sophus Arnet’s cow, looking for leftover hay. This cow famously roamed the town, raiding gardens, opening gates with her tongue, visiting the dock, rubbing against fences and signs. Oblivious to shouts and blows, she draped herself with laundry left on clotheslines, positioned her cowpats in busy areas, obstructed access to buildings, and generally received the blame for anything that went missing. “One man went so far as to suggest facetiously to his neighbor Hamanaka…whose precious woodpile had unaccountably diminished overnight, that perhaps the cow had been in the locality…and so the fun went on.”

Steaming out of Tofino, the Maquinna travelled only a short distance to her next stop at Clayoquot, pulling up at the end of the long curving dock with its railcar that took freight up to the store and hotel. From Clayoquot, the next stop was Kakawis, with freight for Christie School unloaded into scows that came alongside the steamer, and nervous passengers encouraged down the rope ladder into waiting canoes. Then came Ahousaht. On the trip made by Inspector Brodie in August 1918, many cannery workers disembarked there, following their summer’s labour away from home: “It is very interesting disembarking them, as they are all handled in dugouts. These come along side of the ship, which anchors in the bay. The Indians pile into the dugouts, baggage, men, women, children, dogs, pots, pans…Among other things there were small cook stoves, stove pipe, hats, strips of oil cloth and all sorts of paraphernalia. It took about an hour to disembark all the Indians.” In later years, the Maquinna could dock at Ahousaht, navigating up Matilda Inlet to the wharf that had been built in front of the Gibson sawmill.

From Ahousaht, the Maquinna continued through Clayoquot Sound and up the coast, over the years her scheduled stops shifting, changing, and increasing to include any and all short-lived settlements and enterprises: Port Gillam, Bear River, Herbert Inlet, Sydney Inlet—at various times all of these appeared on the steamer’s schedule, along with the various canneries, pilchard reduction plants, mining developments, whaling stations, and logging camps that sprang into being. By 1931, the Princess Maquinna’s schedule listed forty-five locations between Victoria and Port Alice where the steamer could call—half of them scheduled stops, the others serviced on request.

In distant inlets she might be greeted by one person in a canoe, looking for mail or cargo, for even in the most remote locations everyone knew they could count on the Maquinna. “She would often pull into a small float camp or a booming ground and unload the loggers’ cargo out the side hatches,” wrote Bill Moore in B.C. Lumberman in 1977. “She had two large iron doors on her sides down near the water’s edge, and when these were opened freight could be passed out to waiting hands. It may be the middle of the night in a snow storm or it may be in a strong tidal inlet…the captain of the Maquinna would hold her in position while the logger or fisherman took his freight off.” People waiting up these lonely inlets could sense the thrum of the ship’s big engines long before hearing the whistle tooting her arrival; they knew every sound of that ship approaching and leaving, especially the grating sounds of winches and chains. Once on board, everyone revelled in the familiar, welcoming smells: blasts of dark smoke from the funnel, warm gusts from the engine room, the rich aroma of steamy cooking in the ship’s galley.

When the boat stopped for any length of time, local residents could come aboard and treat themselves to a meal. The dining saloon, panelled with “dark expensive wood,” according to Alder Bloom, seemed a place of great elegance, a far cry from everyday life on the coast “Several heavy mahogany tables [were] placed about the room,” Bloom recalled, “covered with fine linen cloths, heavy silverware and fine dishes. All done in true CPR style with a ship’s officer at the head of each table. An immaculate waiter took my order.” Children travelling on the boat were simply awestruck by the impressive surroundings. Bob Wingen recalled, “When we sat down at the dinner table on the boat there was this beautiful dinner service laid out with all this cutlery. We were dumbfounded and the stewards would have to teach us how to handle it all. We couldn’t afford all those knives and forks.” Mary (MacLeod) Hardy has never forgotten the details of dining aboard: the polished banister leading into the dining room, the welcoming smells, the amazement of reading the menu with “new words such as à la mode’ or à la carte’ and the finger bowls, it was a whole new world to us.” The ship’s officers always took their place at tables with the passengers; well-behaved children might even find themselves invited to sit with the captain. In the early 1920s, breakfast or lunch aboard ship cost seventy-five cents; dinner one dollar. By the late 1940s, the price of lunch had increased to a dollar and ten cents. Gene Aitkens described a lunch she and her son enjoyed aboard the Maquinna in 1948: “We had soup, turkey, potatoes, and cauliflower, mixed salad and pudding, tea for me, milk for Art and then a banana. Art also had an apple.” Such workaday fare, though, could not compare to the more exciting midnight suppers, with buffet tables lining the starboard side of the dining lounge and offering cold salmon, roast beef, and turkey; fruit salad, chocolate cake, crème caramel, and raisin pie for dessert—to name only a few items.

On special occasions, the food served aboard the Maquinna could be amazingly elaborate. Take Christmas Day of 1924. The handwritten menu, decorated with sketches of holly, excitedly capitalized every item of the many courses: Salted Almonds and Ripe Olives for starters, followed by a choice of soups: Consommé à la Reine and Cream of Oyster. Then the fish course: Boiled Halibut with Shrimp Sauce and Lobster Salad with Celery, also Boiled Ham with Champagne Sauce. Orange Fritters and Chicken Patties also make an appearance. Then the choices for the main course, including Roast Ribs of Beef with Yorkshire Pudding, Roast Turkey with Cranberry Sauce, and Roast Goose with Apple Sauce, all served with Mashed Potatoes and Green Peas. Dessert next: Plum Pudding with Rum Sauce, Deep Apple Pie, Mince Tartlets, Cream Puffs. To round off the meal: Maraschino Jelly Creams, Nuts, Raisins, Figs, and Dates.

Weddings in all communities along the route often took place to coincide with the arrival of the Maquinna—and sometimes even took place aboard. Ivan Clarke, a Victoria-born tugboat master, arrived at Hot Springs Cove in 1933 on the Maquinna, pitched his tent and decided to stay. With $500 worth of provisions, he built a house and store with lumber salvaged from nearby Sydney Inlet Mine and began catering to fish boats and fishing camps in the area. Thirteen months later his fiancée, Mabel Stephens, arrived at Ahousaht on the Maquinna. The Presbyterian minister, Rev. J. Jones, came aboard and married Ivan and Mabel, with Captain William Thompson serving as best man. Also in 1934, Daphne Guppy and Tom Gibson, who had recently arrived in Tofino to work on gold prospects up the Kennedy River, were married by the ship’s captain on board the Princess Maquinna. Weddings in Tofino often were timed to allow newlyweds to go straight from their wedding reception onto the southbound boat, heading off on their honeymoon. This explains why Tofino wedding anniversaries, for decades, fell on the 6th, 16th, and 26th of the month. On those dates the coastal steamer appeared in town late at night on its return voyage down the coast, heading south to Victoria. The Community Hall buzzed with festivity on wedding days, and according to Ronald MacLeod, “practically everyone in the village would be invited to these events…By midnight, the Maquinna would arrive and the newlyweds would board the vessel under a shower of rice and hearty good wishes for a joyous honeymoon.”

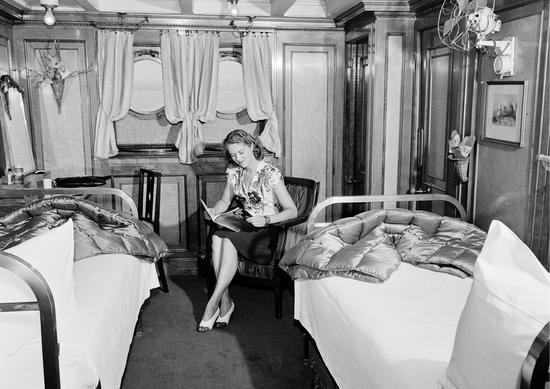

Once aboard ship, stewards would usher passengers into their staterooms. For ten dollars and fifty cents, in the 1930s, Tofinoites could go to Victoria, with a stateroom and all meals included, including afternoon tea and a midnight supper. “She could take 400 passengers,” Alder Bloom recalled, “but the fifty staterooms with their large upper and lower berths could not accommodate everyone. Many people spent the night in the lounges.” Those in the staterooms found the lower berth had its own electric reading light, and the cabins offered two folding seats, a wardrobe, a washstand with a pitcher and basin, and a chamber pot tucked discreetly away. Over time, the Maquinna acquired hot and cold running water in her staterooms.

In the morning, chimes awakened the passengers, as the steward walked up and down, sounding the bell and announcing, “First call to breakfast, first call to breakfast.” Mealtimes had three sittings, with each passenger assigned a time. People could while away some of the hours of travel out on deck, weather permitting, sometimes clustered around the warm funnel of the ship. In good weather, the ship’s crew would be out there chatting to passengers, even playing deck games. The cargo hatches on the ship were forward, and the cabins, smoking lounge, social hall, and dining room aft of the hatches. Cecil Maiden, who travelled often on the Maquinna, recalled the facilities on board with deep affection, despite his assertion that she never proved herself a comfortable vessel. “Those who travelled in her will never forget her,” he wrote, “the strange zig-zag passageways, the unpretentious homey lounge, the tiny smoking room, the cozy dining saloon with its atmosphere of a kindly home.” Everyone eventually spent time in the Maquinna’s central saloon because, as one of her crew commented, “There wasn’t anywhere else to go. Everyone had to be friendly.” Although parts of the deck could be piled high with building supplies and cargo, some stout-hearted passengers regularly chose to travel outside, in sheltered positions on deck, weather permitting. According to Cecil Maiden, some did so even in stormy weather: “they gathered around the warm funnel, as the ship rolled and plunged, the salt sea spray in their faces…the boards groaning and creaking.”

Regular travellers on the route always knew the location of the Maquinna when she stopped, even in the dark and the rain, by the sounds and the smells of each port. According to Anthony Guppy, the reduction plants had “a particularly rancid oily smell,” and a salmon cannery had a “fresh fish smell.” Passengers could also tell without looking if the ship had stopped for a boat landing or at a dock. A boat landing meant that people and goods transferred to smaller vessels that came alongside the Maquinna for loading and unloading; the loud clanging of the big steel cargo doors opening signalled a boat landing. If passengers chose to look out, “down below on a cold misty sea there would be people struggling to unload perhaps a stove, building materials, or boxes of food into a pitching skiff or canoe.” As Captain H.G. Halkett wrote in The Islander in 1980, recalling the Maquinna, “Unfamiliar passengers who may have expected nights of quiet sleep aboard would soon be disillusioned as the chatter and blather of three sets of steam cargo winches created an unholy row in all cabins.” At scheduled stops along the route, passengers soon knew to expect the shuddering of the ship, the sounding bells and whistle, the rattling chains, the hurried footsteps along passageways and decks, and the noisy shifting of freight from within the cargo deck.

For Indigenous passengers, the coastal steamers provided frequent and reliable transport, especially for those travelling to and from seasonal employment at the canneries. Since the early days of the Canadian Pacific Navigation Company, seasonal workers travelled to the canneries in large groups, taking with them the household goods they would need for several months away from home. These travellers did not experience convivial times in the dining saloon, and comfortable berths to sleep in. They travelled “deck class,” sitting out on deck, making little shelters where and how they could, sometimes travelling in the cargo hold in bad weather. When the ship stopped for any length of time, they would take their big iron cooking pots and prepare a meal on the beach nearby, sometimes catching fish right then and there to eat. More privileged passengers often noted the large numbers of cannery workers on board: “a hundred or more Indians, men, women and children…sleeping on deck for two or three nights…On arrival at the cannery…they disembarked with all their weird paraphernalia slung over their shoulders…each carrying their little load.”

Exceptionally, at a time of segregated steamer travel, Father Charles Moser’s diary provides accounts of obtaining staterooms for Christie School students when travelling to and from the school. June 4, 1924, found him at Kyuquot, shepherding a large group aboard the Maquinna: “I had 29 children to take care of after leaving the Whaling Station and at 9 P.M. at Nootka got four more. The 33 spent the night divided in eleven staterooms. For fares and rooms I paid the Purser $146.90.” Three years later, on April 24, 1927, he wrote of children heading back to the villages from Christie School: “Said Mass at 4 AM. When we heard steamer whistle got baggage and children ready…I got staterooms for the girls and placed the boys in the steerage.”

Despite this evidence from Father Charles of Indigenous children occupying staterooms aboard the Princess Maquinna, most often the schoolchildren travelled “steerage” in the cargo area or, if the weather permitted, out on deck. In 1936, Nurse Banfill of Ahousaht accompanied three schoolchildren to Alberni, recounting the trip in her book With the Indians of the Pacific: “As Indians are not allowed to eat or sleep in the quarters used by white people, I found a place below the hatch for the boys to sleep and eat their lunches. Mary, with the features of a white girl, was more or less smuggled into my cabin; sleeping on a leather couch and eating her school lunch.” The boys paid little heed to the restrictions and wandered all over the boat anyhow, to the disapproval of other passengers. “Whenever I took [Mary] out on deck,” Nurse Banfield wrote, “I noticed two wealthy tourists, lounging in chairs…peering down their noses at my little brood and me.” Former students who attended Christie School in the late 1930s and early 1940s still recall how they had to stay below decks. Violet George first travelled to Christie School when she was six years old, with her two older sisters. Her father paid their fares from Nootka Cannery, and the girls went aboard and went down to the hold, where they stayed for many hours before reaching the school. With no benches provided, they sat on their suitcases; a bucket served as a toilet.

Although treated as second-class passengers aboard the coastal steamers, Indigenous folk provided a major tourist attraction along the west coast route. On Boat Days at many stops between Victoria and Kyuquot, skilled artisans from the village sold their baskets and carvings to passengers from the early years of the twentieth century onward. In September 1910, the Colonist noted a group of these vendors gathered in Victoria, waiting for the steamer Tees, “some of the women engaged in weaving hats and baskets, some of the men busily carving small totems and other wares for the tourist trade. Many Kodak fiends were engaged ‘snap-shotting’ the picturesque groups.”

According to Douglas Cole in Captured Heritage, around the time of World War I, First Nations art began to gain prestige in British Columbia, adding a certain cachet to up-market settings. Totem poles and reproductions of Indigenous motifs were featured in murals or as decoration in places like the Empress Hotel and the Lieutenant Governor’s ballroom in Victoria. From 1911 onward, largely thanks to the energies of Dr. C.F. Newcombe, the province made concerted efforts to acquire Indigenous cultural material for the provincial museum—decades after major museums in America and Europe had led the way in pillaging every artifact they could obtain from villages up and down the northwest coast. Local museum interest developed in step with popular interest in the art and design of First Nations, feeding the growing touristic interest in “Indian curios.”

Tourist traffic along the west coast of British Columbia had developed well behind that of Alaska. Boatloads of Alaska-bound tourists travelled by steamer from the continental United States from the early 1880s onward. In 1889 the Alaska tourist traffic had increased to the point that one steamship company alone carried over 5,000 passengers that summer. Tourists swarmed ashore at every small port, keen to see the Indigenous people and to buy their handicrafts. Eventually the CPR woke up to the fact that the same potential existed along the west coast of Vancouver Island and began to capitalize on it ruthlessly.

Once the pulp mill at Port Alice opened in 1917, this town became the turnaround point for “round-trippers,” those curiosity-seeking tourists who boarded the steamer just to see the coast. When the CPR began to promote the west coast route to tourists, its popularity grew rapidly. A publicity leaflet of 1922 notes that “only recently has the route been featured as a tourist route,” and it admits the already serious problem of seasonal overbooking—a problem noted in Father Charles Moser’s diary, with his dour comments about the growing numbers of tourists and the difficulty of reserving bunks. Mike Hamilton had even more to say: “It was a continual nuisance to the coastal residents to find every single cabin and bunk booked up…the company never held sleeping quarters for [coastal residents] which wasn’t fair as they were the mainstay for the service when there were no tourists.”

By the 1930s, publicity about the west coast route made much of the presence of Indigenous people along the way. “The coast is rich in Indian colour,” an undated press release effused, “and the aborigines do much to brighten the way.” A brochure from 1934 promised that “the Indians of this district are still noted for their skill in basket weaving and offer their wares for sale to tourists at various wharfs.” Growing up in Tofino, Ronald MacLeod remembered seeing “how Indian women would take up stations on the wharf and sell woven basketwork, carvings and other artifacts.” Well-circulated publicity images showed totem poles, canoes, and local women busily weaving their baskets. They featured in posters and leaflets and on the front of brochures advertising the “Sunset Cruises” up the coast aboard either the Princess Maquinna or, after her introduction to the coast in 1929, the Princess Norah. Explanatory notes about Indigenous culture told tourists of the locals they could meet. The 1936 brochure stated: “Although the influence of civilization has had much to do with changing the mode of living of these aborigines, much remains to show that in earlier days they were a highly cultured race, enjoying a normal and happy existence.” And later in the brochure: “On the whole a jovial and carefree people, these Indians offer interesting studies. Many opportunities for meeting these people are afforded to travellers during this leisurely and picturesque cruise along the Pacific Coast.”

Before long the CPR advertised the west coast as an alternative to the Alaskan cruises, and people sometimes booked their travel a whole year in advance. Weather permitting, these summer tourists found no lack of entertainment aboard. Shuffleboard on deck became a special attraction, along with dancing and card games in the saloon. Seasickness affected only a “small minority,” according to the CPR’s mendacious publicity; furthermore, those affected “look upon it as an experience to be talked about on their return home.”

Although Inspector Brodie conceded in his 1918 report that the west coast route did have some tourist attractions—his favourites being the cemetery at Nootka and the village of Yuquot, with little good to say about Tofino and Clayoquot Sound—he presented only lukewarm ideas of how to improve the Maquinna for tourists. “A few deck chairs are required,” he wrote, “a phonograph for dancing, and an awning over the after deck. A bath room or two would require to be provided.” Brodie entirely failed to see how popular this route would become. Ten years after his inspection trip, a splendid new steamer was built for the west coast route, specifically to accommodate all the tourists. The much-trumpeted arrival of the Princess Norah on the west coast ushered in a whole new era of tourism on the coast.

Larger and more elaborate than the Princess Maquinna, Princess Norah measured 76 metres long and 14.6 metres wide, offering much more cargo space as well as greatly improved amenities for the travellers. She could carry up to 700 passengers at a time. Of her sixty-one staterooms, four deluxe suites offered private baths, fourteen of the cabins had showers, and all had hot and cold running water. Her berths accommodated 165 people, and up to a hundred at a time could eat in the dining saloon. She had a dance lounge, and on busy runs a band travelled on board to provide music. “She was a sleek and gracious beauty of a ship, a real Princess, with something new—a bow rudder, to help her navigate the narrow passages and inlets of the rugged West Coast,” wrote James Nesbitt.

As a junior reporter for the Daily Colonist, Nesbitt nabbed the assignment of covering the Norah’s highly publicized inaugural run up the coast in April 1929. In later years he recalled the experience: “The very special guests were the Governor General of Canada and the Countess of Willingdon, the latter a peppy lady who missed nothing and had a sharp tongue.” Also on board: Lieutenant Governor Robert Randolph Bruce of British Columbia; the Governor General’s aide-de-camp Major Selden Humphreys; and the mayor of Victoria, Herbert Anscomb. Captain Cyril D. Neroutsos, the “stern, autocratic, every-inch-a-sailor…manager of the CPR’s BC Coast service,” also came along. During these glory days of the CPR ships, James Nesbitt reported, an employee who failed to call Captain Neroutsos “Sir” was fired forthwith, and when inspecting his ships, Neroutsos wore a white glove to enable him to detect the least speck of dust.

When the Governor General’s toplofty aide-de-camp came to Nesbitt’s stateroom to bid him and another reporter to have dinner at the vice-regal table, Nesbitt shook with nerves. He struggled into his first black tie for the occasion and braved a formal dinner. The other reporter, irritated by the tone of the invitation, which began “Their Excellencies command you…,” refused to attend the dinner, suggesting to Nesbitt they both hide in the engine room rather than put up with such condescension. The resulting empty space at the table annoyed Captain Neroutsos and led to the unnamed reporter being suspended from his paper for being rude to the “representatives of the Crown.” Lady Willingdon credited Nesbitt with more journalistic strategy than he possessed when she congratulated him “for having kept [his] rival out of the way.”

“Boatloads of Indians, in native attire, swarmed around the Norah as she came in,” wrote Nesbitt, describing the steamer’s arrival in Ucluelet. Similar welcomes awaited her all along the route, with elaborate presentations from local leaders, community groups, First Nations, and always with crowds of local people flocking to the docks to participate in gala receptions. Ucluelet children had a day off school, and youngsters of all races, Japanese, Indigenous, and others, scrambled aboard the Norah, wildly excited to see the grand new boat with its distinguished guests. Also at Ucluelet, the enthusiastic Lord Willingdon expressed such interest in seal skins that he clambered right into a bin of skins at Edwin Lee’s store to examine them. At Lennard Island, approaching Tofino, a flotilla of Japanese fishing boats and every other vessel imaginable converged to escort the Norah into harbour. George Nicholson’s Miowera, with Ronald MacLeod and many others on board, joined the “fishing boats, tenders, pleasure boats, whaling canoes, small canoes, skiffs, rowboats and whatever else that would float…bedecked in colourful flags and banners.”

Winnie Dixson recalled the lavish ceremony awaiting the visiting dignitaries on the dock in Tofino: “The wharf was lined with these painted backdrops and spruce boughs. Then the Indians did their dances with all the masks. And all the school kids were down there singing the national anthem...Oh, it was a real reception!” Hundreds of people attended, and the Tla-o-qui-ahts invested Lord Willingdon with the honorary rank of chief. Japanese girls danced wearing traditional attire, and Mitsuzo Nakagawa, president of Tofino Area Fishing Co-op, presented the Governor General with a huge sturgeon as a mark of esteem. Dorothy Abraham’s Girl Guides and Brownies stood for inspection and then “danced around the regal party on the wharf, which had been transformed by the veterans into a bower of loveliness.” The Tofino Board of Trade hosted a reception for the illustrious guests; among those honoured, Chief Joseph and Queen Mary of Opitsaht.

The most repeated tale of the viceregal couple’s visit to Tofino on the Princess Norah involves their encounter with the old Scottish prospector Bill Spittal and his famously ugly dog, Joe Beef. The Governor General and his wife agreed to walk up the trail from the dock to look around the village of Tofino. John Cooper, formerly of Long Beach and now a leading citizen of Tofino and Legion president, escorted them—although the escort could have been George Nicholson; accounts vary. After the couple politely admired Cap Thompson’s large dahlia garden and meandered down the road into the village, “who comes limping down the path with his dog but old Bill Spittal…he used to lead [Joe Beef] around on a piece of anchor chain,” Walter Guppy recalled. Bill Spittal, with his tobacco-stained beard, floppy hat down to his eyebrows, old coat dragging on the ground, could not have been less impressed by the august company facing him. Politely, Cooper introduced Bill as one of Tofino’s original prospectors and pioneers. “‘Mr. Spittle [sic], I want you to meet Lord and Lady Willingdon, and I’m their escort,’” Ian MacLeod recounted in one version of the story. “Bill Spittle let out a great big spit of snoose and he said, ‘Howya doing? I’m Bill Spittle from Glenshee, Scotland, and this is my escort, Joe Beef.’”

The Princess Norah continued her triumphal progress up the coast, met with great enthusiasm everywhere. At Port Alice, Father Charles Moser joined the celebrity crowd on board and travelled back down the coast, enjoying the good cheer just as he had on the inaugural run of Princess Maquinna back in 1913. On that trip, as on this, Captain Edward Gillam had charge of the vessel. Gillam had been appointed captain of the Norah, relinquishing command of the Maquinna, and he foresaw finishing his career aboard this newer, larger boat. He did so, but not as foreseen. Three weeks later, Father Charles noted in his diary: “The sad news was told us that our good Captain Gillam had passed into eternity…RIP. He was a good friend of mine.” On board the Norah on her second trip along the west coast, Gillam fell down a short flight of steps and died, likely of a heart attack. In Tofino, Dr. Dixson examined the body, and John Grice, as coroner, signed the death certificate. According to Dixson, Gillam’s face was tranquil.

For the rest of her first season, Father Charles boarded the Princess Norah regularly on his mission trips along the coast—Nootka to Hesquiaht, Hesquiaht to Kyuquot, Port Alice to Kakawis, Opitsaht to Hesquiaht, his usual peripatetic summer—frequently commenting on the new ship and the numbers of tourists on board. “June 4, 1929: SS Pr Norah at Hesquiat at 4 AM...About 20 tourists aboard making the round trip.” In July, Father Charles commented on a special stop the Norah made, anchoring “alongside the survey steamer Lillooet. Chief Surveyor Parizeau came aboard our boat for the sake of dancing until daylight.” Later in the month the priest counted ninety-two tourists on board. He began to find travelling on the Norah a bit too lively for his taste: “July 23, 1929: Left 9 P.M. per SS Norah. Big freight for Kakawis, lumber for fire escapes. Tough salesmen and others on board, dangerous company, not suitable for a priest. Age and experience became me well on this trip. Steamer full of tourists; had a berth in a room with 2 others.”

Despite her more lavish facilities and touristic gaiety, Princess Norah never won the hearts of west coasters as the Princess Maquinna did. She served the coast in tourist season throughout her early years, but increasingly she was deployed on other runs, particularly to Alaska, and also on the Gulf Island run and up to Prince Rupert. Princess Maquinna, despite occasional assignments on other runs, stuck firmly to the west coast of Vancouver Island, becoming known over the years as “Old Faithful.” Following Gillam’s death, several other popular captains served on the Maquinna: Captain Robert “Red” Thompson, then Captain William “Black” Thompson, followed by Captains Peter Leslie, Martin MacKinnon, Leonard McDonald, and R.W. Carthew. Two of the ship’s captains spoke Gaelic fluently, often enjoying a chat with Murdo MacLeod in Tofino; on Boat Days near Christmas they would visit the MacLeod home for a dram of whisky, and Princess Maquinna would leave a bit later than scheduled.

Significant as the coastal steamers were, arriving every ten days at stops all along the coast, the routine movement of smaller boats coming and going in Tofino Harbour, around the Sound, and up the inlets made every day a boat-filled day. Without these boats and all their activity, nothing could happen. Fishing, transport, provisions, communication, recreation—everything relied on boats. Recognizable at a glance to local people, all these fish boats, workboats, scows, skiffs, canoes, rowboats, government vessels, mission boats meant the world to their owners, each one carrying its own cargo of stories. Knowing these boats, their background, their activities, meant knowing what was going on in town and along the coast. Small wonder their comings and goings attracted such interest.

During the many years when Clayoquot cannery operated, from 1895 to 1932, cannery vessels frequently appeared, the two tiny steam-powered tugs Bulldog and Bison or the early fishing boats Iskum, Beth, Eastpoint, and Bertha L., some of the fleet overseen by John Eik, head skipper of all cannery-owned boats. As the years passed, with the arrival of Japanese fishermen, the increase in salmon trolling, and, later, the bonanza years of the pilchard fishery, the numbers of boats coming and going in Tofino Harbour mounted dramatically. Early in the morning, dozens of boats would head out fishing, presenting a calm, silent rush hour of fish boats, outlined against the lightening sky. Dorothy Abraham recalled the scene: “It was a fascinating sight if ever one was up early enough to see them go out in formation, a steady stream, and it was always interesting to see who would be ‘high boat’ for the day.” High boat meant the highest catch of the day—everyone wanted that honour, most often captured by Harold Kimoto and other Japanese fishermen. Among the vessels heading out before dawn, the small, sturdy Japanese salmon trollers usually bore only the initials of their owners as names, including the KK, DE, KM, followed by their fishing licence numbers. The Japanese vessels all fished for the Tofino Trollers’ Co-operative Association. The fish packers awaiting them at the fish-buying station in Tofino Harbour in the 1930s included the chartered Rose N, which packed salmon for the Seattle market, and the Western Chief, owned by the fishing co-op.

The West Coast Advocate periodically reported fishboat activity as if the vessels were alive, setting off on their travels as sentient creatures quite independent of their owners. “Seiner Ginger Boy has gone to Barclay Sound to fish dog salmon…Yankee Boy has arrived to spend a week-end in Tofino.” “The seine boats Kenn Falls and Aliema returned from the [bait] herring fishing at Kyuquot for Christmas.” During the July–August sockeye season, Kenn Falls and other Tofino-based seiners, Aliema, Calm Creek, Annie H., Yankee Boy, Ginger Boy, Silver Horde, Anna B., would head up the inlet for sockeye, joined by numerous seiners from elsewhere on the coast. John Eik and his crew of five sometimes invited local boys aboard Kenn Falls for a week or so as a special treat during the season, giving the boys bragging rights among their friends. Other boats did the same: “I begged to get a couple of weeks on first Roy Darville’s boat Calm Creek, and then on Karl Arnet’s boat, the Aliema,” wrote Anthony Guppy. “They took me on without pay...and knew I just wanted to see how things were done on a seiner.”

Indigenous fishermen operated several of the fishing vessels often seen in Tofino Harbour in the late 1920s and 1930s—Axmaxis, Margaret C., and Skill among them—as well as a Nootka Packing Company seiner skippered for many years by the highly respected Kelsemaht fisherman George Sye. Other local trollers and seiners included Oscar Hansen’s June W and Louis Fransen’s Pete, and many fish boats from other home ports came and went: the Cape May and Ohiat from Bamfield, the Bramada from Alberni, the B.C. Kidd from Steveston, the Newcastle #4 from Vancouver, the Skill from Port Alberni. The United Church mission boat Melvin Swartout became a frequent visitor, and American trollers would anchor in Tofino harbour when weather dictated. Edgar Arnet’s well-known Cape Beale appeared in the spring and fall when he needed to store or pick up gear, which he stored in his father Jacob’s shed. George Hillier’s Ucluelet-based boats also regularly showed up. A successful fishermen on the coast, Hillier started his career hand-trolling from an Indian canoe and subsequently owned Ucluelet Kid, Doolad, and Cupid before acquiring the large Manhattan I, from which he seined salmon and anchovies and long-lined halibut.

A good number of the boats based in and around Tofino had been built there by their owners, John Hansen’s salmon seiner Ginger Boy among them, and many smaller vessels like Anthony Guppy’s Tofino Kid. Many of the best known boats in the area originated at Wingen’s shipyard, including Joe MacLeod’s salmon troller Loch Monar, the Catholic mission’s Ave Maria II, the gillnetter June W, and trollers Sharlene, Bear Island, and Cumtux. John Eik had his seiner Kenn Falls rebuilt by the Wingens in 1935, and the Gibson brothers of Ahousaht commissioned two tugs: Gibson Girl in 1938 and Tahsis No. 1 in 1943. Although most boats built by Tom Wingen and later by his son Hilmar did not remain in Tofino, ranging far and wide in their careers as motor launches, tugs, or fish boats, the launch of any Wingen boat always gave rise to local celebration. Boat launches, especially of larger vessels like George Hillier’s 18-metre seiner Manhattan II in 1941, often turned into gala events involving almost everyone in Tofino, and ending in a dance at the Community Hall. Bob Wingen, Hilmar’s son, remembered how he and his brother Harvey discovered the champagne hidden safely away for boat launches. “We figured that spilling all that good booze at the launch was a great waste. So we got the bottle and worked the wire loose and took the cork out, drank the champagne and refilled the bottle back up with ginger ale and re-sealed it. So a lot of the boats in my time were christened using ginger ale and not champagne.”

T.H. Wingen’s Shipyard had opened for business on the Tofino waterfront in 1929, initiated by Tom Wingen, and later expanded, adapted, and carried on by son Hilmar and grandson Bob. The shipyard grew out of Wingen’s earlier enterprises, the Tofino Boat Yard, which he established with Mike Hogan after moving into Tofino from the family’s original homestead out at Grice Bay, and the Tofino Machine Shop, which Hilmar Wingen opened in partnership with Mike Hamilton in 1917. The earliest Wingen-built boats predate the official opening of the shipyard, the Tofino, built in 1918 for the Stone family, being the first.

At one point the third-largest small-boat shipyard in British Columbia, Wingen’s employed forty-five men by 1944. These included labourers, machinists, cabinet makers, and six Norwegian shipwrights, all able to “lay down a board, mark it out and cut it to shape with a broad-axe, and the damn thing fit!” as Bob Wingen explained. The war years kept the shipyard humming. Renowned for his exceptional craftsmanship, Hilmar Wingen, like his pioneering father, became famed for his ingenuity. Determined to use local materials as much as possible, he devised a method of laminating yellow cedar and yew wood to make ships’ ribs, bypassing the need to import cants of white oak, the tough, springy wood traditionally employed. The Wingens salvaged Douglas fir for boat keels from trees that came down in slides from the mountains above Kennedy Lake, and they used red and yellow cedar for planking. When it came to engines, “by the late 1930s the Wingens were pouring their own bearings and rebuilding engines from the block up,” according to Andrew Struthers, who lived aboard the Loch Ryan, a vessel rebuilt by the Wingens. They created “pistons, heads, rods—right out of raw metal.” Hilmar even built a two-stroke gas engine from scratch.

In the late 1920s and 1930s, when a strong westerly or southeaster blew the offshore pilchard purse seine fleet into Tofino harbour for a “tie-up” day, these boats could be found six abreast at the wharf and on floats. Company-owned boats dominated the scene, each one painted in company colours and flying company pennants—over the years the companies included Nootka Packing Company, Nelson Brothers, BC Packers, Anglo-British Columbia, Francis Millerd and Company, and the Canadian Fishing Company. Local boys loved visiting the pilchard vessels, peppering the fishermen with questions and “learning neat things like net mending and fancy rope splicing,” according to Ronald MacLeod.

The movements of the Tofino lifeboat provided another constant source of interest, even though most trips tended to be routine or practice runs. Still, even the most mundane trip on the lifeboat could be exciting for a young boy, and because his uncle Alex MacLeod worked as coxswain on the lifeboat for twenty-six years, Ronald MacLeod sometimes enjoyed short trips to fill the lamps in the harbour navigational system. He remembered the lifeboat as a “double-ender about 38 or 40 feet [11.5 or 12 metres] in length. It had buoyancy tanks which were supposed to ensure that the vessel would right itself if it ever tipped over... fortunately, an assumption never tested. A canvas canopy from the bow section to mid-ships provided the only cover for the crew.” Occasionally he and his cousins went out on the lifeboat with a delivery run of mail and supplies to the light at Lennard Island. Seas could be huge, and seasickness almost inevitable, but the boys thrilled to watch the large workboat offloading cargo for the light, and crew members battling to hold it in place in a surging sea as a large canvas sling descended from an overhead cable to carry the goods ashore.

Looking out from the town, no one could mistake the larger, official boats that sometimes showed up in the harbour. These included the lighthouse tender Estevan and one of the offshore fisheries patrol vessels, the coal-burning Givenchy, whose Captain Redford spent nearly twenty years (1919–38) enforcing the five-kilometre offshore limit along the West Coast, inside which no foreign vessel could fish. Canada’s other Pacific offshore fisheries patrol vessel, the Malaspina, with Captain Henderson in charge, also appeared from time to time. In the 1930s the hydrographic survey vessel Lillooet became a familiar sight for several years as she worked along the coast. The fifteen-metre police motor launch PML7 also showed up periodically on patrol duty, carrying out the usual jobs of collecting taxes from canneries and from fishermen, monitoring events in First Nations villages, providing assistance to destitute trappers and prospectors out in the bush, or tracking down stolen boats. This boat meant business; handcuffs hung from the wall of the cabin, and she carried a Thompson submachine gun on board. Also appearing from time to time was the Otter, for thirty-five years a passenger vessel all around the coast until purchased by the Gibson brothers in the early 1930s and refitted as a fish packer. She made regular visits until she went up in flames in 1937. The Department of Indian Affairs’ launch Duncan Scott, skippered by Indian agent Noel Garrard, showed up in the harbour fairly often, as did the Catholic mission boat Drummond, succeeded by the Brabant. During the 1930s, the well-known mission boat Messenger II, operated by the Shantymen’s Christian Association, also became a frequent visitor.

The famous Malahat loomed into sight occasionally, now stripped down and glumly functional, working as a log barge for the Gibson brothers at Ahousaht. Built in Victoria in 1917, during the years of American prohibition this 74.5-metre five-masted schooner had served as the most famous of all rum-running vessels out of Vancouver. With immense loads of liquor, she sailed south and loitered in the dangerous offshore waters of “Rum Row,” off the Californian and Mexican coasts. Captained by Stuart Stone for several years during that period of risk-taking and high seas adventure, the Malahat acted as a floating warehouse, remaining largely in international waters and provisioning smaller vessels that ran for shore with their loads of booze packed into gunny sacks. Stone had been involved in rum-running from 1920 onward, starting in a small way on the family’s Alberni-based launch Roche Point, then as master of several important rum-running ships, including Federalship and L’Aquila. Jailed briefly in California in 1927 for his activities, Stone carried on undaunted, in 1929 taking command of the mothership, Malahat. Two years later he married his second wife, Emmie May Binns, daughter of Carl Binns of Ucluelet, aboard the Malahat. Many years his junior, Emmie May lived aboard the Malahat with Stuart for eighteen months, revelling in the adventure and romance. Their time together was cut short by his sudden death in 1933, after he fell ill aboard the Malahat. Built “in the grand old style with a coal burning fireplace in the owner’s quarters and two full size bathtubs,” according to Gordon Gibson, no ship could compare to the Malahat. In her altered state, she served the Gibsons as a self-powered, self-loading and self-unloading log barge until 1937, carrying upward of $15,000 worth of logs at a time. In her last few years, with her engines removed, she served as a lowly barge before foundering in Barkley Sound in 1944, the famous vessel “pounded to pieces by Pacific waves and BC logs,” according to the Vancouver Sun.

By the mid-1930s, Murdo MacLeod’s 11.5-metre Mary Ellen Smith, an inshore fisheries patrol vessel, provided another familiar sight, heading out to monitor salmon streams along a 100-kilometre stretch of coastline, from Wreck Bay to Estevan Point. In earlier years, MacLeod had hired George Nicholson’s 12-metre Miowera, well-known locally for her role in fisheries patrol, freight and passenger charters, and also rumoured to have been a rum-runner. Since obtaining the Mary Ellen Smith, “kindly in a sea and comfortable to live on,” MacLeod could stay out longer and travel farther. His strong voice, singing in Gaelic, could sometimes be heard from shore as he headed out on his patrols. On calm days, voices and scraps of song often carried clearly over the water; Anthony Guppy’s abiding childhood memory of George Maltby recalled the old pioneer in his big red rowboat, returning back up the inlet to his home, tired at the end of a day in town, and talking to his boat: “Come on, old boat, come on, take me home quickly now.”

For boys growing up in Tofino and elsewhere along the coast, their first boats were rowboats or canoes. “When you were a kid in Tofino in those days, because there were no roads, you didn’t want a bicycle like other kids—you wanted a dugout canoe,” Bob Wingen stated. “The Natives would carve them for fifty cents a foot, so an eight footer [2 metres], which was the most popular, cost four dollars.” Looking back to his early days of canoe building in the 1920s and ’30s, Peter Webster of Ahousaht also commented on the prices: “It seems strange now, but in those days a twenty-one foot long canoe [6.5 metres] would sell for about thirty-five dollars.”

The Tofino boys would take their prized canoes to the beach and surf them ashore, two or three boys to a canoe. On occasion, Father Victor at Christie School would call the telegraph station in Tofino, spreading the word that the “surf was up” near the school. “Half a dozen of us would row our dugouts up there and join the native kids from the school and then surf our canoes,” Bob Wingen recalled. “After we’d surfed for a while Father Victor would ring a big bell and we’d all go ashore and go into the gymnasium. The nuns would have us strip off our wet clothes and, after giving us kimonos to wear, served us hot cocoa while our wet clothes dried in a big drying machine they had somewhere. After that we put our dry clothes back on and rowed for an hour back to Tofino. That was a big day for us.” Up at Ahousaht, the young Gordon Gibson also delighted in his first canoe, a gift from his father when he was fourteen years old: “I had more pride in that boat than any we have owned since. It was so tender that if I put up my sail about 2 feet down from the first bow thwart, I could tack close into the wind and shoot back and forth across the Inlet regardless of the wind’s direction.”

As the boys became older, they wanted bigger and more powerful boats. About to turn fifteen, Anthony Guppy told his parents he “had to have a bigger boat if [he] was going to earn any real money.” He purchased an old, unpopular vessel, the Ivy H, used earlier as a fisheries patrol boat and mocked locally as the “Piss Pot.” He put the Ivy H to work, taking customers back and forth to the Clayoquot Hotel; they would pay anything from fifty cents to two dollars depending on their level of sobriety, and he found himself “always helping some inebriated person down the dock from the hotel and then onboard the boat.”

None of the Tofino boys in those years ever could forget the early summer mornings in the harbour with the commercial fishermen long gone, already out at their fishing grounds off Portland Point or Cleland (Bare) Island. The lads then took to their skiffs, rowboats, and canoes, also going fishing. “Mostly in pairs, one rowing and the other tending the lines, a fleet of boys would troll near the kelp beds...along the shores of the several channels that led from the wide-open Pacific Ocean to the sheltered inside waters,” recalled Ronald MacLeod. In the evening, some of these small boats would be out again, hand-trolling for coho along the sandbars and channels among the islands in Tofino Harbour.

At the end of the day, well before dark fell, families in Tofino would be watching, anticipating the return of the various boats, the sounds from the dock. Whatever the season, whatever the reason, someone on shore always waited, someone watched and listened, for the bustle of fish offloading to the fish camps, the sounds of gear being stowed, the careful adjusting of tie-up lines, the progress from floats and docks up to the rough trails and roads leading home, the small boats being dragged ashore. The day would slowly fade and the lights on the harbour markers, initially those kerosene lamps on wooden tripods, guided latecomers in through the channels and sandbars of Tofino Harbour. Another day of boats ended.