Chapter 4: The Boston Men

The end of the American War of Independence in 1783 saw the newly fledged United States setting out to establish a triangular trade route linking the eastern seaboard of the United States with the Pacific Northwest and China. At the time, the young country had few trade goods of its own, so it sought goods elsewhere to trade in China for tea, spices, and other exotic luxuries. This triangular trade route played a key role in establishing America as a trading nation, a century later evolving into the era of the legendary Clipper Ships, which raced across the Pacific, round the Horn, and up to New England carrying tea and spices, just as the age of sail ended and the age of steam began.

Captain John Kendrick and Captain Robert Gray became the first Americans attempting this new trade route and, in the process, the first American traders to enter Clayoquot Sound. Kendrick and Gray both hailed from Massachusetts, where a consortium of merchants invested $47,000 to outfit their two vessels, the Columbia Rediviva and the Lady Washington. On September 28, 1787, they departed Hancock’s Wharf in Boston, setting off for the Pacific Northwest coast to acquire furs for sale in China, where they would load up with tea, spices, and luxury items and make the long journey back around the Horn to the eastern ports of the United States.

Before Robert Gray, aboard the Lady Washington, arrived at Nootka to begin trading, he suffered a personal loss that angered him deeply. Indigenous men at Tillamook Bay in Oregon killed his black manservant, Marcus Lopius. Gray named the location “Murderers’ Harbour.” This episode soured Gray’s dealings with, and attitude toward, all local people of the Pacific Northwest, including those in Clayoquot Sound, dubbed “Hancock Harbour” by the Americans.

Gray first entered the Sound in early September 1788, and Robert Haswell, Gray’s third mate, kept a diary that reveals how the “Boston Men,” as the Indigenous people called the Americans, encountered the Tla-o-qui-aht. The entry also shows the paucity of trade goods brought by the Americans:

After his short stop in Clayoquot Sound, Gray sailed the Lady Washington up to Nootka Sound, arriving on September 16, 1788. There he met the duplicitous John Meares, who did all in his power to dissuade the Americans from cutting in on his territory. Haswell wrote: “All the time these gentlemen were on board they fully employed themselves falsicating and rehursing vague and improvable tales relative to the coast and the vast danger attending its navigation of the monsterous savage disposition of its inhabitants adding it would be madness in us so week as we were to stay a winter among them…The fact was they wished to frighten us off the coast that they alone might menopolise the trade but the debth of there design would be easily fathomed.”

After Meares departed for China, the American traders settled in for the winter in Nootka Sound. Kendrick built an outpost, which he named Fort Washington, at Mowina, now called Marvinas Bay, seven kilometres north of Yuquot, on land he “purchased” from Chief Maquinna for ten guns and a little gunpowder. In their dealings with local people, the British had usually avoided trading firearms for furs, bringing with them from China specific trade items such as iron, copper, tin, metal knives, frying pans, axes, adzes, a variety of tools, cloth, buttons, and the like. The Americans, with limited trade items, had no compunction in trading firearms for furs. In his book The Golden Spruce, John Vaillant commented on Kendrick’s subsequent visit to Haida Gwaii: “[He] will go down as one of the most destructive trade ambassadors in early American history. Kendrick was, among other things, the first man to sell large quantities of arms to West Coast tribes, including the Haida, and it is thanks in part to him that the Queen Charlotte Islands have the bloodiest history of any place on the coast.”

In the spring of 1789, on Kendrick’s orders, Gray set sail south from Nootka Sound in the Lady Washington in search of sea otter pelts, making several stops in Clayoquot Sound to trade with Chief Wickaninnish. Haswell noted in his diary that the villages in Clayoquot Sound were larger and more populous than those at Nootka, estimating Opitsaht to have 2,500 inhabitants. He also commented that the people seemed taller and better proportioned than the Mowachaht, describing Wickaninnish as a handsome man over six feet tall. On March 28, following ten days of trading in Clayoquot Sound, Gray sailed farther south and eventually entered Juan de Fuca Strait. Because of poor weather he did not venture far inside this passage, which some mariners hoped could lead to the Northwest Passage.

While on this trading mission, Gray encountered Spanish captain Esteban José Martínez in the Princesca making his way to Nootka Sound. Viceroy Manuel Antonio Flores Maldonado, commander of the Spanish naval base at San Blas on the Baja Peninsula in the Gulf of California, had sent Martínez north in a further attempt to assert Spanish sovereignty over the entire Pacific Northwest coast. Martínez demanded to know why Gray was sailing and trading in Spanish waters. After Gray convinced Martínez that he posed no threat, Gray continued trading while Martínez headed on to Nootka, arriving there on May 5, 1789. Accompanying him were Captain Gonzales López de Haro in the San Carlos and José María Narváez in the Santa Gertrudis.

Over the next month all remained calm as the Spaniards built a small fort on Hog Island, now Lighthouse Island, in Nootka Sound. They set up two batteries of cannons and claimed Yuquot, which they called Santa Cruz. Martínez hosted banquets for the British and Americans whose ships sat at anchor, but on May 12 this conviviality ended. Martínez seized the British ship Iphigenia Nubiana, along with her captain, William Douglas, and crew, accusing them of anchoring in Spanish waters without a permit from the Spanish king. Two weeks later, with the captive crew of the Iphigenia rapidly consuming his limited provisions, Martínez chose to release Douglas and his ship after Douglas signed a bond that he would not trade for furs and would sail to Hawaii. Once out of Nootka harbour, Douglas ignored Martínez’s warnings and sailed north to continue trading. Unfortunately, Douglas failed to connect with Captain Robert Funter, who had taken charge of the North West America, and had been trading to the north. Entirely unaware of the recent Spanish hostility toward Douglas and his men, Funter returned to Nootka, and on June 8 Martínez seized his ship.

Tensions escalated when British captain James Colnett arrived from China on July 3 aboard his Argonaut. The hot-headed Colnett flatly declared his intention, like Meares before him, of building a trading fort. The Associated Merchants of London and India, a company owned by John Meares and John Etches, had sent Colnett from Macao to establish a permanent base in Nootka Sound, and he was not pleased to find the Spanish already there, embarking on a similar venture. Colnett, who had sailed as a midshipman with Cook from 1772 to 1775 on Cook’s second circumnavigation, and who had seen action during the American War of Independence, adamantly refused to concede that Martínez and the Spanish had any right to Nootka. He declared that Captain Cook had laid claim to the area in 1778 and that Pérez and Martínez, who had sailed with Pérez on his voyage in 1774, had not landed nor had they officially claimed the area for Spain. He also pointed out that John Meares had “purchased” land from Chief Maquinna and had built an outpost in Nootka Sound a year before Martínez arrived.

Losing patience with these arguments, Martínez seized Colnett, confined him, imprisoned his officers, and clapped his men in irons. He took possession of the Argonaut and seized Thomas Hudson’s Princess Royal, to add to the North West America he already held. This aggressive action became known, famously and infamously, as the Nootka Incident; major repercussions followed. To make matters worse, after Martínez had boarded one of the British ships, an angry argument broke out when the unarmed Chief Callicum, a kinsman of Maquinna, came alongside in his canoe, accusing Martínez of being a thief. Martínez shot and killed Callicum, an action that blackened the reputation of the Spanish in the eyes of the Mowachaht for years to come.

Martínez sent the Argonaut and Princess Royal as prizes to the naval base at San Blas, with their captains and crews as prisoners. Surprisingly, he allowed the American captains Gray and Kendrick to continue trading from Nootka Sound and even solicited Kendrick’s help to transport the captive crew of the North West America to Macao. Kendrick gave command of his larger ship, the Columbia Rediviva, to Gray, loaded it with the prisoners and the sea otter pelts he had accumulated, and sent Gray off to China, while he sailed north aboard the Lady Washington in search of furs in Haida Gwaii.

Meanwhile, Martínez began fortifying the Spanish presidio, their small fort, at Yuquot. Combined with the shooting of Chief Callicum, this intensified Chief Maquinna’s suspicion of and animosity toward the Spanish. The Mowachaht chief then chose to leave his own village and go and stay with his brother-in-law Chief Wickaninnish in Clayoquot Sound. The rest of the tribe moved five kilometres north, from Yuquot to the other side of Nootka Island, where they established a new village.

Martínez had turned his original mission into a diplomatic mess. The arrests and seizures he made at Nootka Sound sparked serious diplomatic squabbles between Britain and Spain. He received orders from his viceroy in Mexico to vacate Yuquot and return to San Blas, commanded since 1789 by Captain Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra. The following spring Francisco de Eliza y Reventa sailed north to replace Martínez and take command at Yuquot. In June 1790, Eliza sent one of his officers, Manuel Quimper Benítez del Pino, to explore Juan de Fuca Strait. As he passed Clayoquot Sound, Quimper stopped in to visit Chief Maquinna and assured him that the loathed Martínez no longer commanded the Spanish fort at Yuquot. He suggested that Maquinna return to his home territory. On making further inquiries, and after Quimper gave him a sheet of copper and a sail for his canoe, Maquinna returned to his village. In a further attempt to improve relations between the Spanish and the local people, Commander Eliza visited Clayoquot Sound in March 1791 to meet with Wickaninnish and the Tla-o-qui-aht. Fifty canoes came to greet him, and the following day Wickaninnish invited Eliza and his men to his longhouse, where 600 guests gathered for a welcoming feast. From his visits to Clayoquot Sound in 1790 and 1791, Commander Eliza estimated that the Tla-o-qui-aht had four large settlements, each with some 1,500 people. For the most part, his efforts at restoring goodwill led to friendlier relations between the Spanish and the Nuu-chah-nulth. Not so between the British and the Spanish.

John Meares, whose Associated Merchants of London and India owned the three ships seized by Martínez, pressed the government of Prime Minister William Pitt in London to seek reparations from the Spanish government for his losses, stirring up anti-Spanish public opinion with inflammatory reports of the incidents at Nootka. The British government acted quickly, appropriating one million pounds from the Treasury in case it was needed should an armed conflict occur. Pitt threatened war with Spain, asserting that Britain had the right to trade in areas with no Spanish settlement. With the French Revolution then underway, the Spanish could not rely on their traditional ally and decided that maintaining friendship with Britain might be a prudent policy. Following months of posturing and negotiations, on October 28, 1790, the two nations signed the Nootka Convention, which required the Spanish to release Meares’s captured ships and men, and for Meares to receive 210,000 Spanish dollars in compensation. The two countries eventually reached a territorial agreement allowing for mutual access to the Pacific Northwest, naming Captain Bodega y Quadra and Captain George Vancouver to oversee the details of this truce.

In October 1790, following his release from the fetid San Blas prison, where eighteen of his thirty-one crew had died, Captain James Colnett hove into Clayoquot Sound in his unseaworthy Argonaut, now released by the Spanish and once again under his command. He was in no mood to suffer any further indignities. However, after he arrived in Clayoquot Sound, a longboat with several of his crew failed to return to the ship, and Colnett sent some of his men in a small jolly boat to look for it. Within a few days the longboat arrived back safely, but the search party on the jolly boat failed to return. Colnett sent the longboat out, seeking the others, and a month passed with no sign of either vessel. On November 21, Chief Tooteescosettle, Wickaninnish’s brother, informed the anxious captain that the jolly boat had foundered at the entrance to Nootka Sound and that high winds had prevented the longboat from returning to Clayoquot. Another Indigenous man told a somewhat different story, so Colnett decided to hold Chief Tooteescosettle and another chief as hostages until he learned from the Spanish at Nootka what had happened to his men.

When Colnett informed Wickaninnish that he was holding the two hostages, the chief became furiously angry. Wickaninnish’s sister offered to defuse the situation by taking a letter to the Spanish commander at Nootka, Francisco de Eliza, asking for information. Four days later she returned with news that Tooteescosettle had spoken the truth. The jolly boat had indeed foundered; no one survived, the crew disappeared, and none were seen again. With that, Colnett released his hostages and set about repairing his ship. Bad feelings continued to fester, and on December 31 the Tla-o-qui-aht attacked the Argonaut. The English retaliated, firing the ship’s cannons on the village of Opitsaht. With no trust remaining between the Tla-o-qui-aht and Colnett, he set sail for Macao in 1791 after wintering in Clayoquot Sound. Colnett’s name and that of John Meares remain well known in Clayoquot Sound, with Mount Colnett and Meares Island named after them.

On August 29, 1791, American captain Robert Gray sailed into Clayoquot Sound following his circumnavigation of the globe in the Columbia Rediviva. He returned with the intention of establishing a winter base there, well away from the site of the previous tension between the British and Spanish at Nootka. While Gray had been travelling, his commander John Kendrick had “purchased” from Chief Wickaninnish 840 square kilometres of Clayoquot Sound, centred on Opitsaht, for four muskets, a large sail, and a quantity of powder. After acquiring this land, Kendrick built a small trading outpost on an island in “Fair Harbor” near Opitsaht which, like his base in Nootka Sound, he named Fort Washington. This island has never been identified.

In a location he called “Adventure Cove” in Lemmens Inlet on Meares Island, Gray and the fifty men under his command cleared land and built a ten-by-six-metre, two-storey log structure complete with two chimneys, built with some of the 5,000 or more bricks he brought from Boston as ballast. Wary of the Tla-o-qui-aht, Gray mounted two of the ship’s guns and cut musket loopholes in the walls of the building he called Fort Defiance. The Americans also constructed several cabins, a blacksmith shop, and a boat-building shed outside the fort, as well as two saw pits. They began building a forty-five-ton sloop using timbers, stern post, and stem that Gray had brought with him from Boston. They purchased some boards, “which we procured from the natives for a trifling consideration of iron,” according to John Hoskins, the Columbia’s supercargo (clerk), and also felled fir and cedar trees that they whipsawed into planks; others they fashioned into masts and spars.

On Christmas Day 1791 the “Boston men” decorated their fort and ship with evergreens, bunting, and flags, and cooked twenty geese and “whortleberry” (huckleberry) pudding. They invited Chief Wickaninnish and some of the Tla-o-qui-aht hierarchy to join them for Christmas dinner, at which they proffered toasts to one another, played games, and sang songs. Before Wickaninnish and his party paddled off after midnight, Gray fired a salute from the Columbia’s guns. Wickaninnish reciprocated with a feast to which he invited some of the Americans from Fort Defiance. By February 1792, all of this conviviality and friendship came to an end. The Tla-o-qui-aht appeared to be making preparations for a war against neighbouring tribes, and Gray feared they might attack him and his men in order to capture his ship and acquire guns, which Wickaninnish coveted.

Gray’s cabin boy, a Hawaiian lad named Atoo, who had earlier tried to defect from Gray’s crew to join the Tla-o-qui-ahts, found himself embroiled in the mounting tensions. One of Wickaninnish’s brothers told Atoo to wet the crew’s priming powder in order to weaken their defences. Under pressure from Gray, Atoo confessed the proposed plot and the captain hastily posted more guards. Several canoes loaded with warriors paddled near the fort one night shortly after. Hoskins wrote: “It was a beautiful starlit night…the natives gave a most dismal whoop. This was between one and two o’clock in the morning. The people who belonged to the Fort flew to their arms and those who belonged to the ship was by no means behind them. In less than five minutes every man was to his quarters with arms and ammunition ready for action…We continued to hear the most dreadful shrieks and whoops till day began to dawn.”

Angered by this threatening display, Gray reached a fateful decision. He decided to leave, but not before wreaking havoc. He hurriedly launched his new ship, the Adventure; tore down Fort Defiance; and, using the chimney bricks as ballast for his new ship, sailed out of the Sound. As he left, he sent three boatloads of his crew into the largely deserted village of Opitsaht, ordering them to burn all of the houses there. John Boit, the ship’s sixteen-year-old fifth mate, recorded in his diary: “I’m very sorry to be under the necessity of remarking that this day I was sent with three boats all well manned & armed to destroy the village of Opitsatah; it was a command I was in no way tenacious of & am griev’d to think that Capt Gray should let his passions go so far. This village was about half a mile in Diameter, and Contained upwards of 200 Houses…This fine Village, the Work of Ages, was in a short time totally destroy’d.” The exact location of the American Fort Defiance remained a mystery for over 150 years until, in 1966, local historian Ken Gibson, after much searching, confirmed its location in Lemmens Inlet on Meares Island.

Gray sailed north and anchored in Nasparti Inlet, north of Kyuquot and just below the Brooks Peninsula. A war canoe manned with twenty-five local men, followed by others in a number of canoes, approached the Columbia in what seemed a suspicious and hostile manner. Gray ordered the crew to battle stations and armed all hands. John Boit recounted what happened next: “Capt. Gray order’d us to fire, which we did so effectually as to kill or wound every soul in the canoe. She drifted along the side, but we push’d her clear, and she drove to the north side of the Cove, under the shade of the trees. ’Twas bright moon light and the woods echoed with the dying groans of these unfortunate Savages.”

Following this incident, Gray sailed south and for nine days attempted to find a way across the dangerous bar at the mouth of the vast Columbia River. Failing to find a way upriver, he returned northward again and on April 28 met at sea with Captain George Vancouver aboard the Discovery. Vancouver had been sent by Britain to re-establish his country’s claim at Nootka; he was heading there to meet and negotiate with the Spanish commander Bodega y Quadra and had sailed right past the mouth of the Columbia without realizing its existence. Even after conversing with Gray, Vancouver remained skeptical about the river’s presence.

With that, Gray again turned south and this time, on May 11, he found a way over the treacherous sandbars that guard the Columbia River, which he named after his ship, the Columbia Rediviva. He traded with the local people at the mouth of the river and on May 20 exited the river, then set sail once again for China. In 1981, nearly two centuries later, in recognition of Gray’s exploration of the Columbia River, and in honour of his circumnavigation of the globe in 1789–90, NASA named its space shuttle Columbia after his ship. In 1858, when asked to provide a name for the latest Crown colony of her Canadian dominion, Queen Victoria chose the name British Columbia. By then, the Hudson’s Bay Company had long used the name “Columbia” to describe what is now southern BC and northern Washington State. To distinguish the area north of the 49th parallel, established in 1846 as the international boundary, the queen added “British” to the name.

Captain Bodega y Quadra arrived in Nootka Sound with three ships in April 1792 and spent four months there awaiting the arrival of Captain George Vancouver. He used his time well, learning about the area and the people. The diplomatic and well-liked Quadra went to great pains to improve relations with the Mowachaht people, paying special attention to Chief Maquinna, always giving him the honoured place at table and serving him personally. His negotiating skills smoothed over many local disputes, and his support of Maquinna helped prevent a war planned against him by the Ahousaht and Tla-o-qui-aht.

Captain George Vancouver arrived at Nootka in August 1792. He and Quadra, representing their respective countries in diplomatic capacities, came to like and respect each other, despite communicating through interpreters, and often in writing. Strongly impressed by Quadra’s diplomacy and politeness toward the local people, Vancouver noted “with a mixture of surprise and pleasure how much the Spaniards had succeeded in gaining the good opinion and confidence of the people.” In their amicable but inconclusive meetings, Vancouver and Quadra agreed to call what is now Vancouver Island “The Island of Quadra and Vancouver,” but did not achieve much toward clarifying the terms of the Nootka Convention. They decided to let their respective governments do the negotiations. As time passed, the urgency of the English/Spanish dispute over the territory faded away. Sea otter prices fell due to an oversupplied market, the expectation of finding a Northwest Passage abated, and the Spanish finally relinquished their claim on the Pacific Northwest. On October 15, 1795, they tore down their presidio at Yuquot and returned to Mexico, leaving Nootka as a free port.

Following negotiations at Nootka, Captain Vancouver sailed south to California. After wintering in Hawaii, in the spring of 1793 he returned to continue his surveying work on the northwest coast. In early June, when mapping Dean Channel, on the mainland just north of Vancouver Island, some members of his crew rested in Elcho Harbour near what is now Bella Coola. Six weeks later, fur trader and explorer Alexander Mackenzie arrived in that same bay by an entirely different route. He and his party had reached the coast by crossing the North American continent by land, the first Europeans to do so. On a rock in Dean Channel, Mackenzie famously inscribed “Alex Mackenzie from Canada by land 22nd July 1793.” He related in his diary that local people told him of the recent activities of longboats and surveying crews in their area. Mackenzie and Vancouver very nearly met, missing each other by only a matter of weeks.

Captain Robert Gray’s destruction of Opitsaht on his departure from Clayoquot Sound in April 1792 put intense strain on relations between the Nuu-chah-nulth and the fur traders. At the same time, competition mounted between British and American traders. John Kendrick had taken trading to a new level by pre-purchasing skins from the local tribes, thwarting attempts by British traders to buy skins. In June 1792, when William Brown, a British trader on board the Butterworth, arrived at what remained of the village of Opitsaht, the Tla-o-qui-aht refused all his offers. His frustration growing, Brown sent sailors ashore at another unnamed village to acquire what furs they could. His crew resorted to violence, cutting the otter skins from the backs of local people, and killing four. Wickaninnish’s musket-armed warriors retaliated, killing one sailor and wounding four others. Infuriated, Brown took revenge when sailing out of the area. He seized nine Tla-o-qui-ahts from their fishing canoes, whipped them, and threw them into the sea. His accompanying ship, Jenny, then used the swimming men as target practice for its cannons. Of the nine men, four were chiefs, and one a brother of Wickaninnish.

Year by year, Wickaninnish held greater control over trade with the Europeans, and suspicion and mistrust grew on both sides. With the Tla-o-qui-aht chief now in possession of over 200 muskets and two barrels of powder, the potential for violence also increased steadily. In May 1793, when American trader Josiah Roberts arrived in Clayoquot Sound on his Jefferson, Wickaninnish would only agree to trade with the Americans if two of the ship’s officers remained ashore as hostages while trading took place aboard ship. If trade took place on land, one of the chief’s brothers would remain on the ship as hostage. The following winter found Roberts and the Jefferson in Barkley Sound. After one of his men was killed while hunting, Roberts took his revenge. Imitating Gray’s actions at Opitsaht, he destroyed the village of Sechart in March 1794, his armed boats firing their swivel guns, smashing houses and canoes. “After having sufficient satisfaction for their depravations on us,” as first officer Bernard Magee put it, the Jefferson sailed from Barkley Sound. In 1795 another American ship, the Ruby, commanded by Charles Bishop, successfully traded with Wickaninnish, but this appears to have been the last ship to conduct any peaceful trade for sea otter skins in Clayoquot Sound.

By 1800 the fur trade on the Pacific Northwest coast saw the Americans in the ascendency; they had eight ships plying the area for furs that year, while the British had only one. In 1801, twenty American and three British ships sailed the coast, all seeking the dwindling supply of “soft gold.” According to records compiled by early British Columbian historian F.W. Howay, about 450 fur trading vessels visited the North Pacific coast between 1774 and 1820. More than half flew the Stars and Stripes; ninety-three the Union Jack; and the red-and-yellow-striped flag of Spain flew on forty-three ships. Between 1790 and 1818, traders carried some 300,000 sea otter pelts to China from the northwest coast. With the price of a pelt over the same period averaging between twenty-five and thirty dollars, overall the trade netted somewhere between $7.5 and $9 million. By the turn of the century, with the sea otter population dramatically reduced, and because of the establishment of land-based trading posts west of the Rockies by the Hudson’s Bay Company, the Northwest Company, and John Jacob Astor’s Pacific Fur Company, the maritime fur trade began to die out. As it faded, the pent-up indignities of the past decades led to yet more tragic incidents.

In March 1803, following an affront to Chief Maquinna by Captain John Slater, and after years of insults perpetrated on Maquinna and his people by British and American traders, the Mowachahts attacked and beheaded all but two of the twenty-six-man crew of the American ship Boston near Yuquot. John Jewitt and John Thompson, the only survivors of the Boston, became slaves of Chief Maquinna for two years. Jewitt’s highly prized talents as a blacksmith may explain their survival, and on the whole they received good treatment. Chief Wickaninnish attempted on several occasions to purchase Jewitt from Maquinna. In 1805 another trader rescued the two men, and on his return to New England Jewitt published the daily journal he had written during his time in captivity as A Journal Kept at Nootka Sound. In 1815, in collaboration with Richard Alsop, a much expanded version of the diary appeared under the title A Narrative of the Adventures and Sufferings of John T. Jewitt. Because Jewitt had been highly observant and an active participant in the daily life of the local people, his account provides an invaluable early record of Nuu-chah-nulth life. Published and reprinted many times, it made Jewitt into a minor celebrity, although he sank into obscurity in later life. Tellingly, a passage in the Narrative reveals that he understood why his ship and fellow sailors fell victim to an attack. “Many of the melancholy disasters have principally arisen,” he wrote, “from the imprudent conduct of some of the captains and crews…insulting, plundering and even killing [the local people] on slight grounds. This, as nothing is more sacred with a savage than the principle of revenge…induces them to wreak their vengeance upon the first vessel or boat’s crew that offers, making the innocent too frequently suffer for the wrongs of the guilty.”

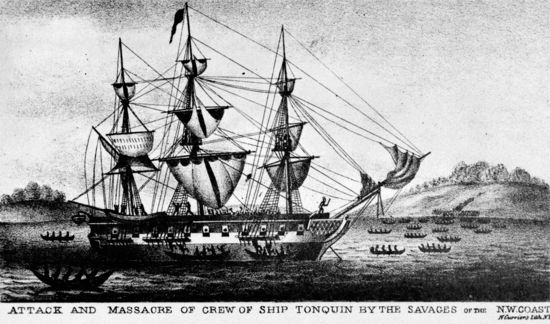

The downward spiral of relations between fur traders and locals continued, becoming ever more disturbing. In 1810, Captain George Washington Ayers of the American ship Mercury took a dozen Tla-o-qui-aht sea otter hunters to California’s Farallon Islands where, having promised to return them home after the hunt, he abandoned them. Only two managed to make their way back, and the Tla-o-qui-aht resolved to exact revenge on the next ship that arrived in Clayoquot Sound. Enter the Tonquin, owned by John Jacob Astor’s Pacific Fur Company, based at Fort Astoria, Oregon. In June 1811, with a crew of twenty-three men, and captained by the quick-tempered Jonathan Thorn, this ship arrived in Clayoquot Sound, anchoring in Templar Channel opposite Wickaninnish’s summer village of Echachis.

Trading progressed well for a few days, but Thorn’s harsh and uncompromising manner and his open insults in dealing with Nookmis (also spelled Nokamis), Chief Wickaninnish’s trade representative, inflamed the Tla-o-qui-aht. Thorn rejected the advice of his experienced supercargo Alexander McKay, and relations soured. McKay had travelled with Alexander Mackenzie on his famous journey across the continent, arriving with him at Bella Coola in July 1793. He had considerable experience as a trader, but to no avail. Under Thorn, relations with the Tla-o-qui-aht reached crisis point during trade negotiations aboard the Tonquin. The Tla-o-qui-aht attacked, killing the captain and all but six of the crew. That night, five of the survivors escaped in a ship’s boat under cover of darkness, leaving the badly wounded ship’s clerk, a man named Lewis, on the Tonquin. The following day an estimated 200 Tla-o-qui-ahts boarded the seemingly deserted Tonquin, bent on plunder. With the decks crowded, a tremendous explosion suddenly tore the ship apart. Apparently Lewis had managed to crawl into the bowels of the ship to ignite the large supply of gunpowder; in effect, he became a suicide bomber. Over eighty bodies were blown all over the bay, with debris, including canoes and trading blankets, strewn across the water. The surviving Tla-o-qui-aht later captured the five crew members who had escaped, killing all of them and leaving alive only the Indigenous interpreter, Joseachal, who had boarded in Astoria. He witnessed the destruction of the Tonquin from shore.

William Banfield wrote an account of the Tonquin’s dramatic end based on what he heard from the Tla-o-qui-aht. His article appeared in the Victoria Daily Gazette of September 9, 1858.

The story of the Tonquin, possessing all the tragic drama of frontier violence, a massacre, and individual heroism, eventually inspired a Hollywood movie. Filmed in the Philippines in 1941 and directed by Frank Lloyd, who also directed Charles Laughton in the 1935 classic Mutiny on the Bounty, this film embellished the story of the Tonquin with a love interest, featuring Carol Bruce as a beautiful stowaway. Cast members included Walter Brennan as Captain Thorn; Canadian Indigenous actor Jay Silverheels, later famed as the Lone Ranger’s sidekick, Tonto; Nigel Bruce, later to play Dr. Watson alongside Basil Rathbone’s Sherlock Holmes; and Leo G. Carroll as Sandy McKay, one of Carol Bruce’s admirers. Entitled This Woman Is Mine and later renamed Fury of the Sea, the Hollywood version of the Tonquin’s terrible end never became a classic of the silver screen. It did receive a nomination in the 1942 Academy Awards for Best Musical Score (Richard Hageman), along with nineteen others. It did not win.

Tla-o-qui-aht oral history, and the account of the Indigenous interpreter, Joseachal, indicate that following the explosion the Tonquin did not sink immediately, and only the stern had been blown off. The Tla-o-qui-aht attempted to tow the hulk westward toward Echachis Island, but southeast winds prevented progress. They began towing it eastward, with the wind, toward Tin Wis Bay (MacKenzie Beach) on the Esowista Peninsula, hoping to beach it there. Before they could do so, the badly damaged ship sank. Nearly a century later, in 2003, a local fisherman snagged an old anchor on the bottom of Tin Wis Bay. Local diver and underwater explorer Rod Palm retrieved the anchor, with the help of several others. It is widely held to be the anchor of the Tonquin. On a coast littered with wrecks and maritime disasters, the Tonquin has attracted more interest than almost any other. Sometimes called the Holy Grail of wrecks, the Tonquin has proved endlessly fascinating for underwater archaeology enthusiasts.

The Tonquin incident marked the end, in any meaningful sense, of the maritime fur trade in the Pacific Northwest. By the time this ship sank, much profit had been made: mostly by international interests in the fur trade, some by individual traders, and a very limited amount by the Nuu-chah-nulth people of Vancouver Island’s west coast. Certainly this trade introduced the coastal people to the often harsh reality of doing business with outsiders, and to the sometimes—by no means always—useful benefits of acquiring goods. The sea otter trade opened the way for future trade and for later settlement, which would bring unimagined consequences to the Nuu-chah-nulth. Chief Wickaninnish, one of the most powerful figures in this initial fur trade, did not live to see its ongoing impact on his people. He died sometime between 1817 and 1825.